Impressionism – A Detailed Movement Overview

The Impressionist era is one of the most significant of the 19th century. Impressionism saw a revolution in the style, technique, and intention of painting. Throwing out the traditional painting playbook, Impressionist painters like Mary Cassatt and Edgar Degas tried to capture the rawness of the world around them. The Impressionist style has loose brushwork, a lack of transition colors, and a sense of impermanence. In this article, we take a deep dive into the style, artists, and concepts integral to the Impressionist movement.

An Introduction to Impressionism

Certainly one of the most influential artistic movements of the 19th century, Impressionism was an intentional revolt against the strict guidelines of the pre-Impressionist art world. Throwing aside the need for realism and the focus on the natural world, Impressionist artists sought to portray the world through a lens of personal experience that reflected our inner world too. The progression of the Impressionist movement was slow and difficult, and we explore that development in this article, as well as taking a look at some of the most common practices and the most famous artists of the movement.

The Development of the Impressionist Movement

The Impressionist movement began at the beginning of the second half of the 19th century, and it lasted in various facets until roughly 1910. During this time, Impressionism morphed several times, and different periods are associated with vastly different techniques, subject matters, and styles.

In this section of the article, we explore the Impressionist movement as it developed throughout the end of the 19th century.

A Revolutionary Movement: Impressionism and Official Art

At its heart, the Impressionist movement was a revolutionary art movement. Impressionist artists rejected many of the traditions and techniques of other painting styles, particularly Romanticism. Impressionist artists were not alone in challenging these conventions of artistic beauty and the relationship between the artist and the State. Realism and Naturalism rejected many Romantic traditions, and Impressionism has several roots in these styles.

Roots in Realism

The first art movement to defy the Parisian establishment in the mid-19th century was Realism. Gustave Courbet was the pioneer of Realism, and he believed that the art of official institutions was blind to reality. At the time, an oppressive regime firmly gripped the French, forcing much of the public into severe poverty.

Despite the rampant poverty, the art of the time focused on mythological and classical narratives, extravagant depictions of the natural world, and idealized nude figures.

In 1855, Courbet financed and held an exhibition of his work. Not only did his work sit opposite the official traditions in concept, but Courbet held the exhibition directly opposite the Paris Universal Exposition. Impressionism found inspiration in Realism’s rejection of perfectly catered subject matters removed from lived reality. Impressionist subject matters are far removed from the glorified and valorized historical heroes of official paintings.

Natural Inspiration

The Naturalism movement emerged around the same time and had close associations with Realism. Although the two share many similarities and are often confused, there are distinct differences. Realism sought to present the world as it were, without frills or fancies, while Naturalism centered around the natural world as a subject matter. Naturalism rejected the mythological heroism and historical contextualization of conventional art.

While painting en plein air is often primarily associated with Impressionism, it was a central feature of the Naturalism movement. As early as the 1820s, Naturalist artists like Jean-Francois Millet and Jean-Baptiste Camille Corot were creating sketches of the countryside, trees, and rural people en plein air in the Barbizon forest. The Barbizon School emerged around this time, and this marked a growing international fascination with painting the natural world in all of its unaltered glory.

The desire to capture the natural world in its exact form is a fundamental part of the Impressionist movement.

Unlike Naturalism, however, Impressionist painters do not attempt to capture the world in hyperrealistic detail. Instead, Impressionist painters want to capture an “impression” of the natural world. This impression includes the artist’s subjectivity.

Early Impressionist Exhibitions in Paris

The revolutionary nature of the Impressionist art movement began to pick up speed in 1863. The official annual art salon was the pinnacle of the French art world. Several Impressionist artists like Paul Cezanne, Édouard Manet, and Camille Pissarro were not allowed to exhibit their works at this salon. As a result of their exclusion, these artists created the “Salon of the Refused,” where they could show their works. Emperor Napoleon III sanctioned the salon to placate the artists, but the exhibition caused great public controversy.

One of the most controversial paintings in this exhibit was Le Dejeuner sur l’Herbe, which Manet painted in the same year. This painting featured clothed men and nude women enjoying a picnic. Perhaps if these were conventionally idealized nude female figures, this painting would not have caused so much controversy. These were, however, modern women, and their state of nudity suggested activities that were far more sexually explicit than convention allowed.

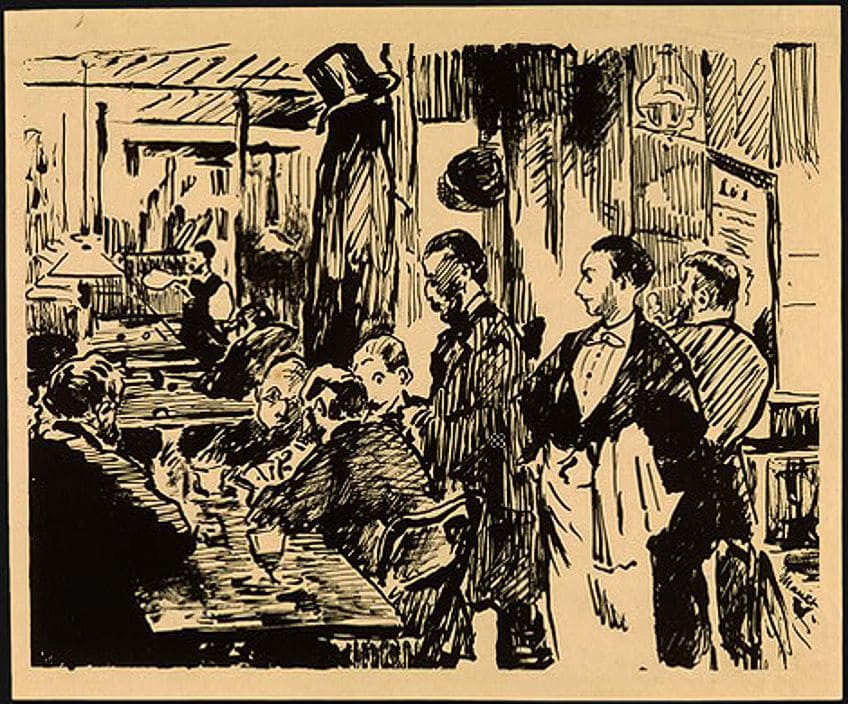

French Cafes: Impressionism and Diversity

The Impressionist art movement was incredibly diverse in terms of subject and artist compared to the official conventions. French cafés played an integral role in developing this Impressionist diversity because they were popular venues amongst Impressionist painters. Artists like Alfred Sisley, Pierre-Aguste Renoir, Camille Pissarro, and Paul Cezanne would frequent Café Guerbois in Montmartre. These artists would meet with other like-minded creatives, including photographers, critics, and writers.

Within this group, there was diversity in personalities, political opinions, and financial situations.

While Berthe Morisot, Degas, and Gustave Caillebotte came from upper-class families, Renoir, Monet, and Pissarro came from merchant families. Alfred Sisley was Anglo-French, while Mary Cassatt was both a woman and an American. Many believe that the sheer diversity in this group of creatives drove the immense creativity that emerged from their collective ventures. Even within the Impressionist movement, we can see the diversity in style and technical practices.

The Anonymous Society of Artists, Painters, Sculptors, Engravers, and More

Before 1874, the term “Impressionism” did not identify this creative collection. The artistic collective did not have a uniting style, but they all shared a distaste for the overly academic and stringent conventions of fine art traditions. In the 1860s, this collective decided to form a commercial cooperative to establish creative independence and financial security.

Many of these artists experienced limited financial success, and the Parisian salon exhibitions did not accept their works.

The collective held its first series of exhibitions in photographer Feliz Nadar’s studio, but they did not begin to call themselves Impressionists until their third show in 1877. Most of these exhibitions actually cost the artists money, and they did not receive much public attention for the first few shows. While their later exhibitions did attract larger audiences, many of the artists still failed to sell many works, and some remained very poor.

The Impressionist Movement

In a hostile review of the creative collective’s 1874 exhibition, Louis Leroy accused the group of only painting “impressions” of things. Leroy grabbed the Impressionism term from Monet’s 1873 painting, Impression, Sunrise. Despite the hostility with which they received this moniker, they began to embrace it. In later decades, they also called themselves “Independents,” a name stemming from the rebellious opinions of the Societe des Artistes Independants.

Several Impressionist painters formed this society in 1884 as they attempted to distance themselves from the conventions of artistic academia. The artists who practiced under the Impressionist title had vastly varied styles and techniques. They did, however, share a common interest in representing visual perception with a focus on ephemeral moments of the modern world with a basis in transient optical impressions.

Photography Impressions

Photographic development was an essential driving force behind much of the Impressionist philosophy. Through the lens, photographers can capture a single, fleeting moment in time, creating a direct imprint of reality on a two-dimensional surface. Photography influenced Impressionism in two distinct ways.

Firstly, the ability to capture any moment transformed our understanding of what it means to be worthy of visual recreation.

Traditional French painting centered around historically valorized, mythological subjects and glorified portraiture of leaders and heroes. Photography facilitated the pictorial preservation of all kinds of new and previously overlooked scenes, landscapes, and people.

Many Impressionist painters found inspiration in this new-found ability to represent overlooked parts of reality. Artists painted bustling side streets, squares, and café scenes that reflect the vibrancy of the evolving urban world and also a new feeling that even the most mundane aspects of this world were worthy of recording.

The second reason why Impressionism is indebted to photography is due to the concept of spontaneous composition. Furthermore, photography can capture a moment in time and a location in space at the same instant. Impressionist painters sought to capture this same sense in their paintings.

A fantastic example is Place de la Concorde, a painting by Degas that captures a Parisian public square. This painting is not merely a painting of this square, but all the people and animals moving through it at the exact moment Degas witnessed it.

The bodies are arranged in haphazard motion, and this precise ability to capture a moment in space could only come from understanding and appreciating photography.

Key Impressionist Ideas

Before we dive into the historical development of the Impressionist style and some of the more notable artists, we should look at some defining characteristics of Impressionist-era paintings. What is Impressionism and how did the style differ from what came before it?

Impressionist painting styles directly contrasted the traditional brushwork and compositional techniques of the Romantic and Realism eras. In order to get an Impressionism definition, there are several key techniques we need to consider, including the brushwork and color, perspective and composition, and the influence of scientific and technological developments.

Loosening Up the Brushwork

One of the most notable features of the Impressionist painting style is the brushwork. In contrast to the smooth and barely visible brushwork in Romantic and Realist paintings, Impressionist painters used looser and bolder brushstrokes. Impressionist painters used shorter brushstrokes and placed strokes of vastly different colors next to each other. Colors were mixed as little as possible on the canvas, exploiting the concept of simultaneous contrast, making the colors appear more vivid.

Painting on a white canvas was another way that Impressionist artists could emphasize the vibrancy of color.

Impressionist painters also used much lighter colors than in previous eras, using white and light shades to capture the movement of natural light. The greys and darker shades in many Impressionist paintings were mixes of complementary colors, and black paint was avoided by artists practicing true Impressionism. This technique further emphasized the brushstrokes. Many critics of the Impressionist era believe that these brushstrokes and color use make Impressionist paintings appear unfinished and amateurish.

Composition and Perspective

In Impressionism, photorealism was not the most important element of a painting. The looser and more obvious brushwork discarded the clarity of form that helped distinguish the principal parts from the lesser elements of Realistic and Romantic paintings. Impressionist painters also abandoned the three-dimensional perspective and the portrayal of perfection and symmetry of previous eras.

For Impressionist painters, the artist’s role was to translate the world as it appeared directly onto the canvas. This perspective found beauty in the imperfections and momentary changes in the world around us.

A new painting exercise also became common practice among Impressionist painters who longed to capture the world more intimately. Painting en plein air, or outside at the scene, rose in popularity during the Impressionist era. Artists like Monet found that painting within the compositional environment lent them greater accuracy in capturing a single, imperfect moment.

The Influence of Scientific Development

The development of the camera was heavily influential to the Impressionist perspective. The camera can capture a split-second moment in time in the frame. Many Impressionist artists sought to mimic this effect, and they tried to capture the optical effects of light. Impressionist painters also aimed to capture minute shifts in other ambient features of the world like weather changes.

This intention, combined with their use of light colors and bold brushwork, allowed the artists to capture the fleeting nature of existence.

Impressionist painters also took advantage of other technological developments, like premixed paint tubes, which facilitated their painting en plein air. Synthetic pigments also became increasingly popular and widely available during the Impressionist era. Impressionist painting techniques made heavy use of these new pigments like viridian, ultramarine blue, cerulean blue, cobalt blue, and cadmium yellow.

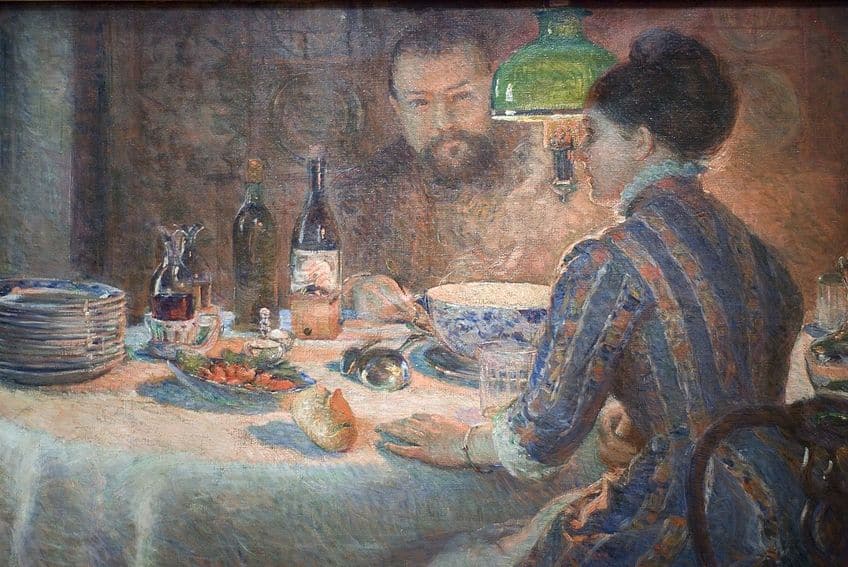

The growing pace of technological development also influenced the subjects of many Impressionist paintings. While Impressionist landscapes are amongst the most well-known themes, Impressionist painters also loved to capture intimate scenes at cabarets and cafés, opera houses, and horse races. Paintings from the Impressionist movement document the growing industrialization of Paris in the middle of the 19th century, and urban Impressionist compositions capture a sense of alienation within a growing metropolis.

The Trends, Concepts, and Styles of Impressionism

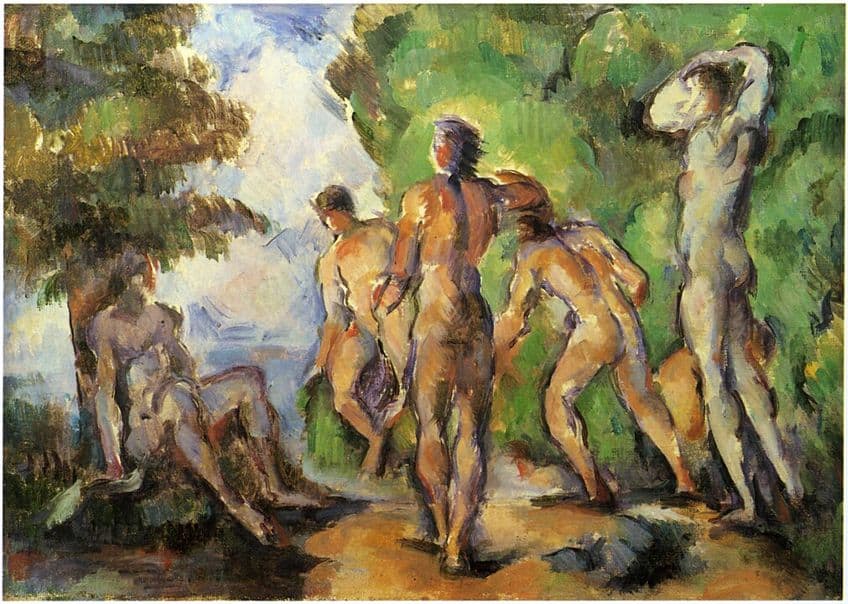

From painting outside to the fascination with bodies and movement, Impressionist styles, concepts, and trends are vast and varied. Fundamental trends in the subject matter include the intimate lives of women, bustling cityscapes, and the study of bodies in space.

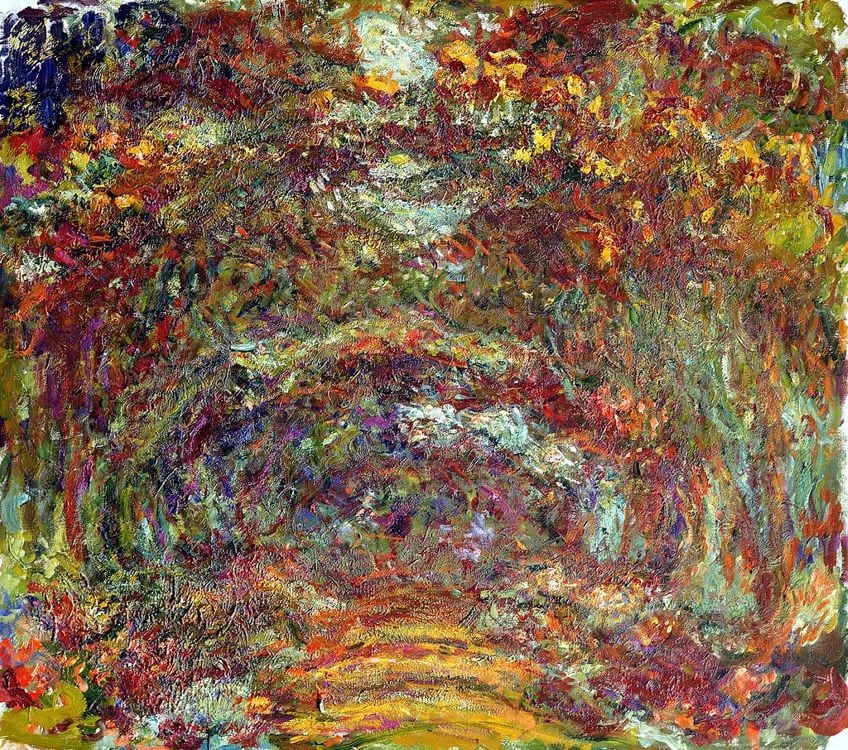

Painting en Plein Air

Stemming from the Naturalist artist’s practice of painting within a scene, Impressionist painters spent many hours outside in various weather conditions, capturing beautiful impressions. Painting en Plein air was central to the development of Impressionism’s two primary motifs.

By painting outside, artists were able to observe and capture the world in different states, marking the passage of time. Painting outside also allowed Impressionist artists to refine their ability to capture the effects of natural light. For example, Monet’s Haystack series painted between 1890 and 1891 depicts the same haystack in varying light and weather conditions.

Many Impressionist painters painted outside, including Alfred Sisley, Camille Pissarro, Berthe Morisot, and John Singer Sargent. Monet was able to master the depiction of natural light so well that he became one of the most celebrated Impressionists.

Monet painted outside at all times of the day, carefully documenting shifts in ambiance. In his garden in Giverny, Monet spent hours creating spontaneous impressions of the landscape. Using unmixed colors with very soft brushstrokes, Monet manages to create a sense of subtle vibration, as if nature was living and breathing on the two-dimensional canvas. Monet also employed a “wet-on-wet” painting technique, which translated into blurred boundaries and softer edges that hint at a three-dimensional world.

An Impression of a City

Impressionism was closely associated with Parisian society, and many artists documented the growing metropolitan nature of the city. The 1860s renovation of Paris by Baron Georges-Eugene Haussmann greatly modernized the city. One of the most prominent renovations was to broaden the sidewalks, which soon became hubs of social activity.

With the city’s reconstruction came the concept of the flaneur, or idler who roams the city’s public spaces. Impressionist paintings that document this changing cityscape focus on the flaneur as a metaphor of the modern individual within a growing metropolis.

Gustave Caillebotte depicts these themes of urban modernity in his city panoramas. Caillebotte also focused on the psychology of the individuals within the cityscape.

Caillebotte has a more realistic style than many of the earlier Impressionist painters, but atmospheric changes and emotionality still permeate his works. His painting Paris, Rainy Day, completed in 1877, depicts a flaneur strolling along a boulevard dressed in a characteristic top hat and black coat.

Impressionist artists like Monet and Pissarro also translated the urbanized cityscape into their own unique styles, focussing on the quality of light and movement. These works stress the geometric arrangement of the public space within the city by carefully delineating the streets, trees, and buildings.

For example, in 1897, Pissarro completed The Boulevard Montmartre, Afternoon, which brings the characteristic Impressionist strokes of color to the cityscape. Impressionists like Monet and Pissarro communicated the rising tempo of modern urban life with crude brushstrokes and characteristic strokes of color.

The Human Body and Impressionist Artists

While many Impressionist artists loved to paint landscape scenes outside, others, like Degas, Cassatt, and Renoir, did not believe that painting should be a spontaneous exploit. Degas was a highly skilled portrait artist and draftsman, and his preferred subjects were indoor scenes depicting modern living. In Degas’ most famous paintings, we can see people from all walks of life, from ballet dancers preparing themselves for performances to musicians in the orchestra pit. When considering Degas’ painting style, we can see how much stylistic variation there was below the Impressionist umbrella.

Degas tended to use thicker and more intentional brushstrokes, and he delineated his forms with much more clarity than artists like Pissarro and Monet.

The fascination with painting human forms also had a psychological facet for artists like Cassatt, Renoir, and Morisot. Renoir represented the daily activities of various members of his neighborhood in his characteristic saturated and vibrant colors. Renoir loved to document the social activities of Parisian society.

Although Renoir was known to paint en plein air, he was not interested in capturing atmospheric changes within the scene. Instead, Renoir used loose and light brushwork to highlight the human form and communicate the emotional qualities of his subjects.

Impressionism and Women

So far, we have primarily considered male Impressionist artists and their exploits. During the 19th century, female artists faced many barriers in entering the field and creating their works. When painting human figures, male Impressionist artists tended to paint them within public settings like city cafés. In contrast, female Impressionists, like Berthe Morisot, focused on the private lives of late 19th-century women. As the first woman to exhibit her works with the Impressionists, Morisot highlighted the highly personal and domestic sphere of female society in her rich compositions.

The maternal bond between child and mother was a favorite subject for Morisot, and her 1872 painting, The Cradle, is a wonderful example.

Berthe Morisot, Eva Gonzales, Mary Cassatt, and Marie Bracquemond are the four most prominent Impressionist women. In 1879, Cassatt began exhibiting her depictions of private and public female life with the Impressionists.

Cassatt depicted the female figure within the urbanized cityscape as in her 1879 painting, At the Opera. In this painting, and many of her others, Cassatt includes several innovative techniques, which would herald her later modern art developments. These innovations included the employment of almost garishly bright colors and the flattening of three-dimensional space.

Famous Impressionist Painters and Their Works

We have briefly touched on many of the most prominent artists of French Impressionism. From Manet to Mary Cassatt, there is such variety in Impressionist styles and subject matters. Taking a closer look at some of the most influential Impressionist painters gives us a true insight into the diversity of the movement.

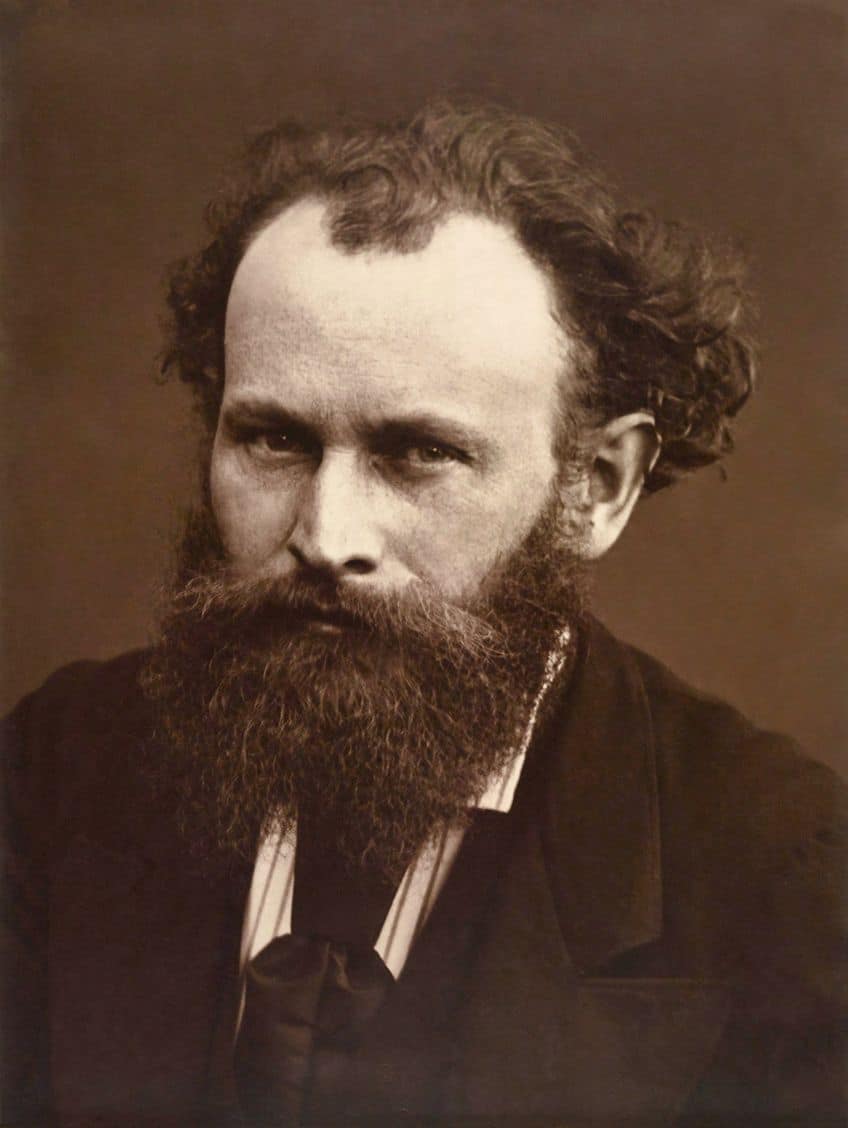

Édouard Manet (1832-1883)

Many art historians credit Manet as one of the first and most prominent Impressionist painters to emerge on the Parisian art scene. Manet was born into considerable wealth and political prestige, but he rejected the future his family mapped out for him and threw himself into painting.

Growing up, Manet admired many of the Old Masters, but in the early 1860s, he began to use a looser, more innovative painting style with a brighter palette.

His early works from this period, such as Le Dejeuner sur l’Herbe in particular, were essential in developing the French Impressionist style. Today, many consider these paintings as watershed moments in modern art.

Manet preferred to focus on depicting everyday life through his paintings, capturing scenes on the streets, in boudoirs, and in Parisian Cafés. This archetypal modern subject matter and his proudly anti-academic style began attracting the attention of other fringe artists. It was Manet’s courage and insistence on creating art that deviated from the convention that gave impetus to the Impressionist group.

Le Dejeuner sur l’Herbe (1863)

We could not consider any other painting by Manet as his most influential and profound work. It was this painting that lit the Impressionist fire and changed the course of art history. The painting presents two fully clothed men having a picnic with two completely nude women while another barely dressed woman bathes behind them. Manet removed the nude female figure from contexts that legitimized it, like Orientalism and mythology.

The naked women also stare assertively out from the canvas, directly challenging the preconceptions of the viewer.

The suggestively nude and imperfect female figures depicted in this painting made it one of the most controversial works of the 19th century, and it permitted other artists to break conventional boundaries regarding acceptable subject matters. Manet’s style, as can be seen in this painting, is different from many other Impressionists like Monet. Although he routinely exhibited alongside other Impressionists, Manet preferred to use exaggerated color contrasts and sharper outlines. Without a doubt, this is one of the most famous Impressionist paintings.

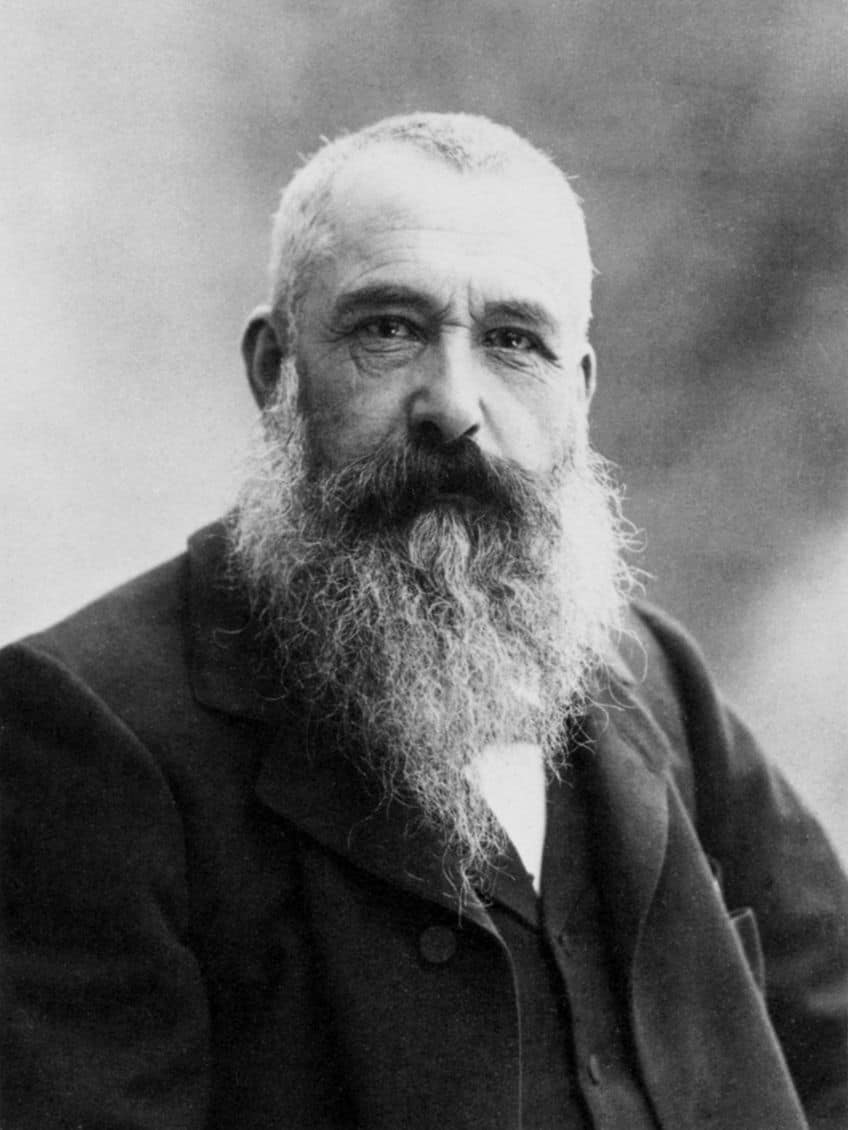

Claude Monet (1840-1926)

Now one of, if not the most, prominent Impressionists, Monet was committed to documenting the ever-changing French countryside. While Manet is credited with sparking the Impressionist movement, Monet is regarded as the founding father. Monet was the most prominent Impressionist who practiced the philosophy of expressing one’s visual perceptions of the world directly as you found them.

Monet frequently returned to particular landscapes with his canvas and easel to paint the scene in different lighting or atmospheric conditions.

With his characteristic use of short and almost frenzied brushstrokes, Monet was able to translate optical impressions onto canvas to the point where they almost vibrated with life. Monet spent much of his later life in his house in Giverny, where he would spend his days painting his glorious garden in varying lights and conditions. Perhaps one of his most famous series of works is the Water Lilies series, where he repeatedly painted the waterlilies on his pond. When Impressionism became known and celebrated globally, Monet became one of the most famous Impressionist painters, and many American Impressionists flocked to Giverney to learn from the master.

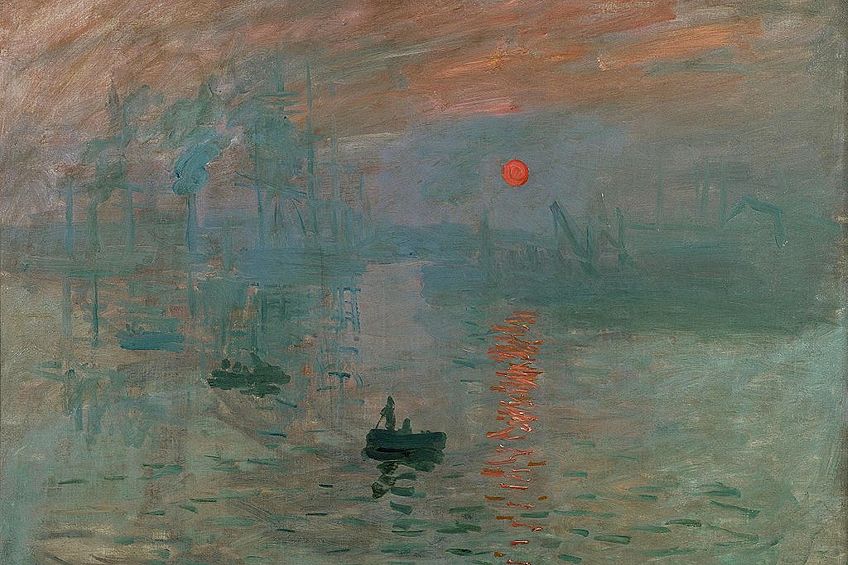

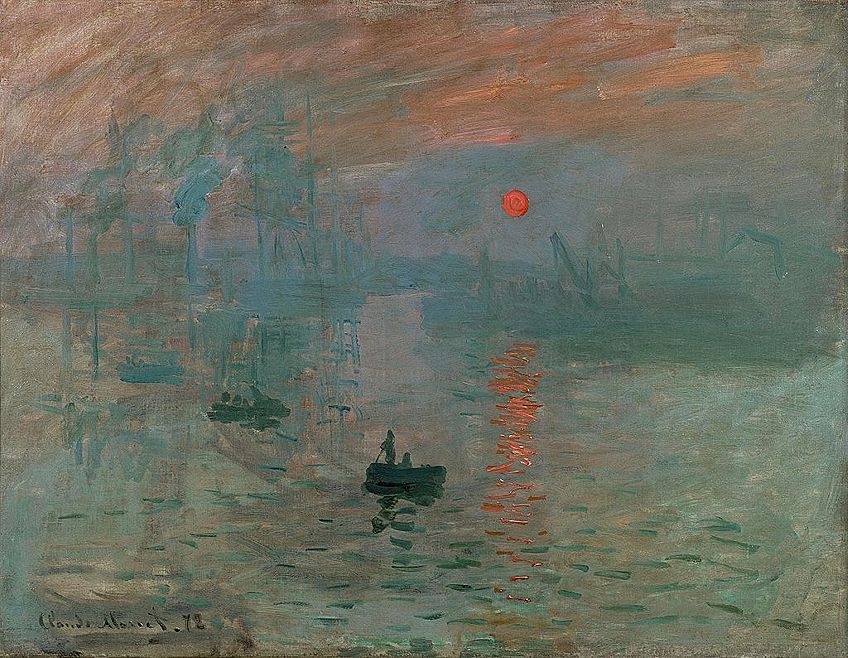

Impression, Sunrise (1872)

Like Manet’s first influential piece, this painting is often cited as the work that birthed the Impressionist movement. Although it was painted well into the time that Monet was working in this style with other Impressionist artists, it made such an impression and represented the epitome of the Impressionist style. The continuity of the color palette is the most striking feature of this painting.

Monet manages to simultaneously distinguish and meld the land, sky, and sea, with all being bathed in gentle hues of orange, blue, and green.

The city in the painting is not the subject, and neither are the anonymous men in boats starting on a day of fishing. Instead, the subject of this beautiful and warming painting is Monet’s sensory impression of the moment. This painting of time-specific effects of light was indicative of a new style of painting.

This painting is one of several created by Monet in 1872. This approach is typical of Monet’s artistic process. By capturing the same scene in different lights and atmospheric conditions, Monet could capture the movement of time and how this shifted the quality of light.

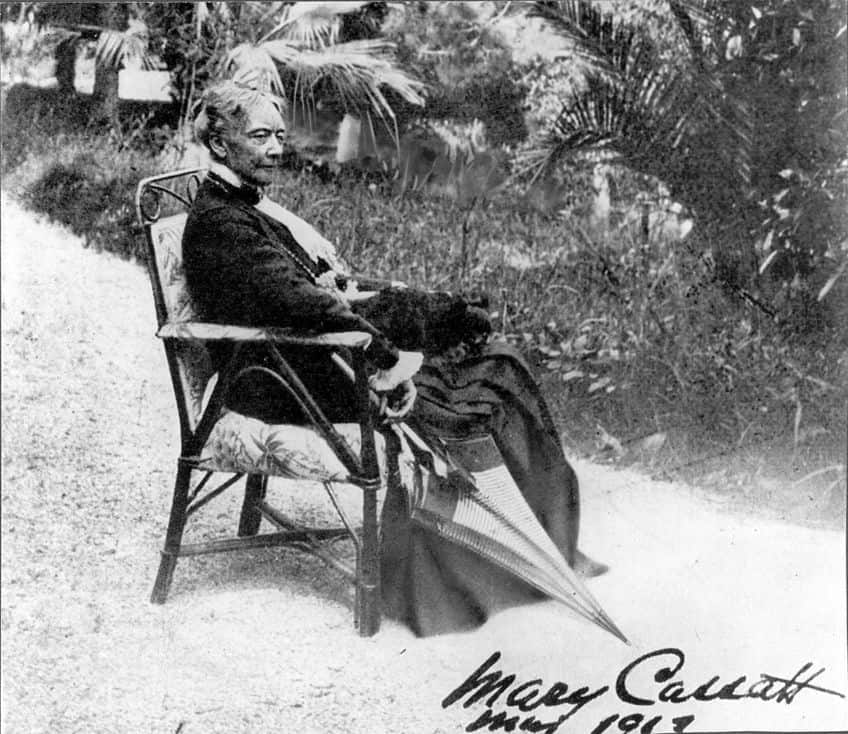

Mary Cassatt (1844-1926)

Originally born in Pennsylvania, Mary Cassatt spent much of her life in France, where she met and befriended other Impressionist artists, including Degas. Mary Cassatt came from a culturally conventional family, but she longed to break free from the path set out for her. To the disgust of her family, Cassatt studied at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts.

As a woman, Cassatt was vastly outnumbered throughout her education, but this only fueled her desire to succeed.

Today, Cassatt is considered one of the three most prominent female Impressionists, and as a life-long feminist, her work tends to focus on the private and public lives of women. In particular, Cassatt often depicted the bond between mother and child in a very intimate fashion. Like many Impressionists, Cassatt initially submitted her paintings at many of the official salons. However, she soon became disenchanted with the snobbery and sexism of the conventional French art establishment.

In the Loge (1877-1878)

This is one of the most famous Impressionist paintings and is the epitome of Mary Cassatt’s work. The female subject of the painting is sitting in the Palais Garnier, which was a social hub in the Paris Opera for the city’s elite. The opera as a social hub was not only a place for cultural entertainment. The opera also served as a place where you could see others and be seen. The female subject is leaning forwards, gazing through her binoculars at the stage below.

On the opposite side of the opera house, a man is mirroring this pose.

The composition of this painting is a witty commentary on the act of looking. Not only is the act of looking a central part of the Impressionist philosophy, but the painting may be a commentary on the fate of a female artist who cannot escape the gaze of men as she seeks to be the observer.

Life After Impressionism: Post-Impressionist Movements

As we have seen, there was great variety within the Impressionist movement, yet despite the diversity in circumstance and style, the group met and collaborated often. Together, between 1874 and 1886, the group held eight exhibitions of their work, but they began drifting apart throughout this period. By this time, many Impressionist painters felt they had mastered the early Impressionist style and needed to pursue other styles and techniques.

Other members of the Impressionist group felt disheartened by their continued lack of financial success.

The Impressionist Pinnacle

For much of its life as a movement, Impressionism was not widely accepted or celebrated. Its reputation as a revolutionary art form and the continued preference for traditional conventions left many Impressionist artists struggling financially. Impressionism was finally accepted as the result of Paul Durand-Ruel.

Duran-Ruel was a London-based art dealer who met Monet in 1871 and bought and exhibited many Impressionist works in London for many years. Although sales were slow at first, towards the end of the 1880s, Duran-Ruel began to show Impressionist paintings in America, where their success grew immensely.

Thanks to Duran-Ruel, American buyers purchased more Impressionist paintings than any artist ever sold in France. The value of Impressionist works shot through the roof, and Monet eventually became a millionaire. As its popularity grew, Impressionism became an academic dogma, with many American painters arriving in Giverny to learn from Monet, the most famed Impressionist painter. Despite this success, Impressionist painters continued to explore other artistic avenues, leading to Post-Impressionism.

International Impressionism

As Impressionism was finally beginning to attract financial success and global recognition and the French Impressionists began exploring other styles, many international artists began exploring Impressionist techniques.

In America, in particular, the Impressionist movement began picking up steam. The American Impressionist movement, featuring artists like Maurice Prendergast, Childe Hassam, and William Merritt Chase, began gaining traction. Childe Hassam is most well-known for his vivid impressions of cityscapes and coastal scenes, and William Merritt Chase touched the bourgeois metropolitan milieu of late 19th-century American society and landscapes with Impressionist techniques.

Maurice Prendergast created a distinctive style of North American Post-Impressionism.

Members of the Australian Impressionism School, like Arthur Streeton and Tom Roberts, used dusty color palettes and Impressionist techniques to evoke Australian landscapes.

The British Impressionist movement is one of the most significant international Impressionist movements of the late 19th century. A liquid and loose painting style was pioneered by James Abbott McNeil Whistler, an American expatriate who lived in London. Abbott McNeil Whistler’s Nocturne series evokes the glamor and gloom of nightfall over the River Thames.

Another British Impressionist, Philip Wilson Steer, was a pioneer of Impressionist seascapes, painting in South-West England and Cornwall. Scott William McTaggart used the wilder coastal landscapes of his country to create stormier Impressionist seascapes. Other influential Impressionist movements appeared across Europe, with the most notable being in Germany, Belgium, Holland, and Denmark.

Post-Impressionism

When French Impressionism began to fade, the younger members of the group split off in various directions. Many short-lived groups and schools were formed and disregarded. For the Post-Impressionist movement to develop, there had to be a necessary divide in Impressionist thought.

While some artists and schools used Impressionist techniques to communicate the internal emotional life of the artist, others sought to refine the ocular techniques that underlay the Impressionist style.

Post-Impressionist Subjectivity

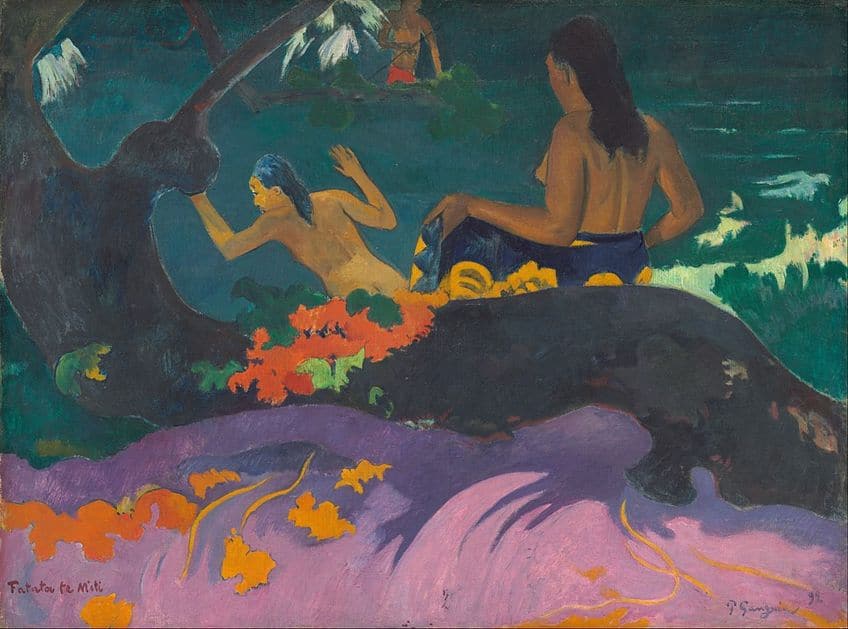

Groups like the Nabis, Synthetists, Cloisonists, and individual artists like Vincent van Gogh and Paul Gauguin belonged to the first group. In the late 1880s, the Cloisonists emerged using large areas of bright color, delineated by dark and thick lines. This group got their name from the “cloisonnes” or individual panels of medieval stained-glass windows that their style mimicked.

Influential painters in the Cloisonists include Louis Anquetin and Emile Bernard. Both of these artists spent time with van Gogh and members of the Pont-Aven school in Brittany, including Paul Gauguin and Paul Serusier. All four of these artists were also associated with the Synthetism style. The origins and techniques of Synthetism were almost identical to that of Cloisonnism. Synthetism, however, lacked the bold outlines of the Cloissonist style.

Gauguin’s Vision After the Sermon, which he painted in 1888, is one of the most iconic works of the Synthetist-Cloisonnist style. The Talisman, completed in the same year by Serusier, is another great example of this style, and it became the guiding light for the Nabi group.

The Nabi group combined the emotive and bright color blocks of the Cloisonist style with psychological and religious symbolism. The Post-Impressionist movements began to intersect with other art movements of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, including Expressionism and Symbolism.

Post-Impressionist Technicality

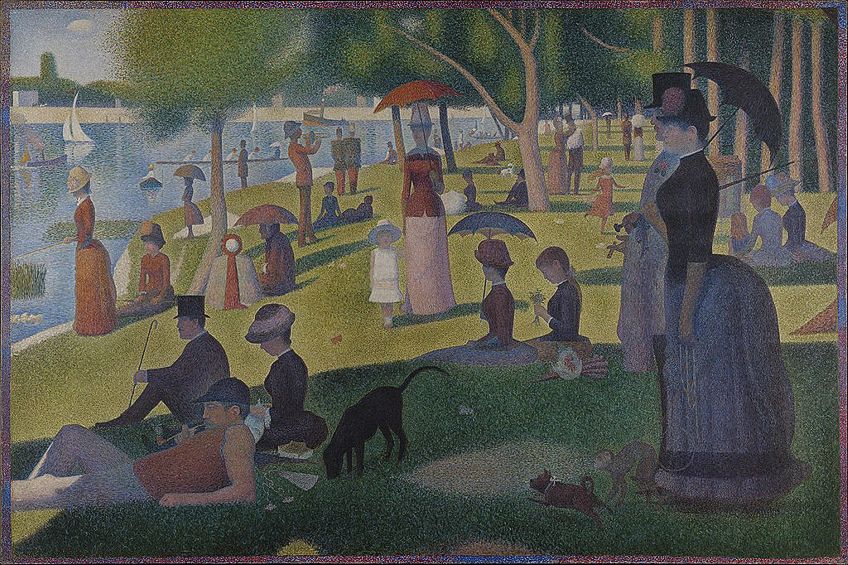

In contrast to the more emotionally-centered works of Cloisonnist-Synthetist painters, we have the more scientifically inflected reaction to Impressionism. Pointillism is the most prominent scientific Post-Impressionist movement, and it included artists like Paul Signac and Georges Seurat. These artists used late 19th-century scientific developments in optics as the basis for their stylistic development.

The discovery that the eye perceives colors in the form of different wavelengths of light and that this light is then combined within the eye to recreate the image was particularly important to this group of Post-Impressionists. The Pointillists believed that if an artist were to juxtapose tiny dots of primary colors in just the right manner, the eye, from a distance, would see the desired tone. These artists also believed that this use of color would create much lighter tones than conventional methods.

A Sunday on La Grande Jatte, painted by Seurat between 1884 and 1886, is perhaps the most well-known example of Pointillism. Many art historians believe that the work of van Gogh, with its hypnotically repetitive brushstrokes, combines the pronounced and stylized qualities of Pointillism and the heavily emotional appeal of Synthetist-Cloisonnism.

French Impressionism, although relatively short-lived, has made a lasting impression on the world of artistic expression. The developments in technique and style opened the doors to art that breaks conventions and pushes boundaries. There is something so raw and true about Impressionist paintings that makes us return to them time and again.

Take a look at our Impressionism art webstory here!

Frequently Asked Questions

Who Are the Most Famous Impressionist Artists?

Alongside Monet and Camille Pissarro, some of the most famous Impressionist artists are Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Edouard Manet, and Paul Cezanne. Many of these artists were not allowed to present their work in the official salon in France, due to the critic Louis Leroy. Their first exhibition was less official and soon they were allowed to participate in the annual salon in the late nineteenth century.

What Is Impressionism?

The Impressionist movement grew out of the revolt against the strict requirements of the art world at the beginning of the nineteenth century. They disregarded strict natural realism and focussed on presenting the world through their own inner experiences.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Impressionism – A Detailed Movement Overview.” Art in Context. March 24, 2021. URL: https://artincontext.org/impressionism/

Meyer, I. (2021, 24 March). Impressionism – A Detailed Movement Overview. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/impressionism/

Meyer, Isabella. “Impressionism – A Detailed Movement Overview.” Art in Context, March 24, 2021. https://artincontext.org/impressionism/.