Gustave Courbet – Artistic Biography of This French Realist Painter

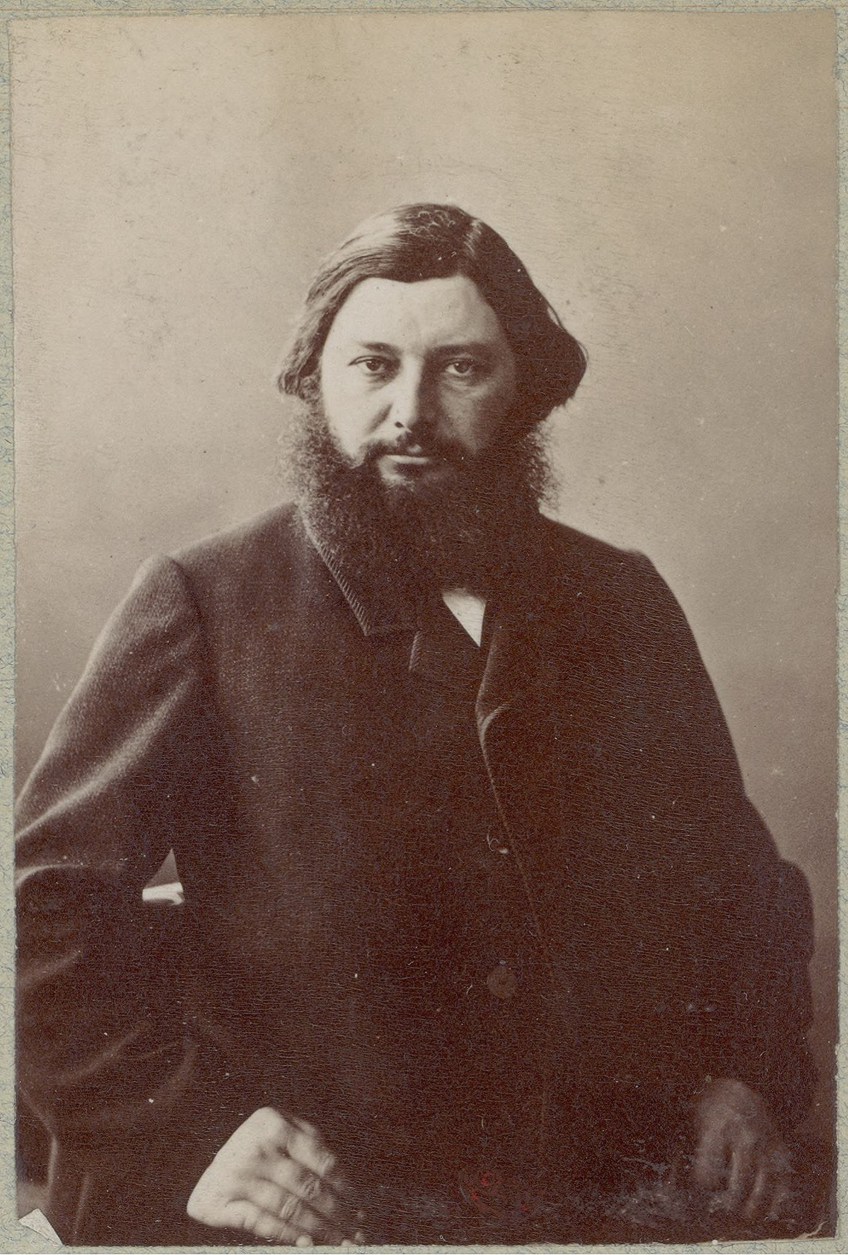

Gustave Courbet was regarded as a pivotal figure in the mid-19th-century birth of Realism. Gustave Courbet’s paintings, which rejected the classical and dramatic traditions of the Academy’s French painters, emphasized the physical truth of the things he witnessed – even if that actuality was simple and flawed. As a devout Republican, the French realist painter regarded his Art as a way to advocate for his hometown’s farmers and rural folk. Historians have increasingly viewed Gustave Courbet’s artworks as an essential precursor to other early modernist artists such as Claude Monet and Édouard Manet.

The Life of French Realist Painter Gustave Courbet

Gustave Courbet’s Realism may be regarded as part of a larger investigation into the physical universe that captivated academia in the 19th century. But it was his disdain for the French Academy’s strictures that motivated him the most in Gustave Courbet’s paintings.

Unlike other French painters of that period, Gustave Courbet’s artworks disregarded Classical or Romantic approaches in favor of taking lowly images of country life – themes normally associated with small genre painting – and transforming them into material for grand historical painting.

| Nationality | French |

| Date of Birth | 10 June 1819 |

| Date of Death | 31 December 1877 |

| Place of Birth | Ornans, France |

Childhood

Courbet was born in June of 1819 in the little rural town of Ornans, to a caring family in gorgeous surroundings. He loved strenuous physical activities such as swimming in the Loue River with his siblings and roaming in the family’s meadows and vineyards. Courbet enjoyed being the focus of attention at school and amusing his peers with his charm and charisma.

Despite a thorough general education, Courbet’s academic art instruction was substandard. He got tuition from a lesser Neoclassical artist when he was 14, which most likely provided him with a base to respond against. He pursued pre-law at a local college at his father’s insistence, but he was unhappy until a sketching professor at the institution asked him to take painting classes at a home workshop.

This boosted his conviction in his creative abilities and inspired him to embrace his ambition.

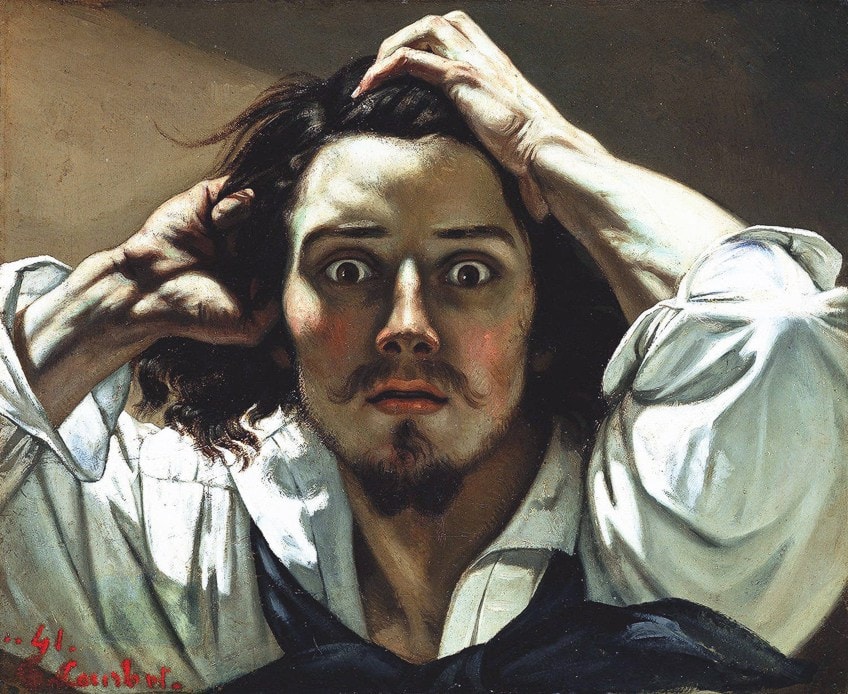

Early Years

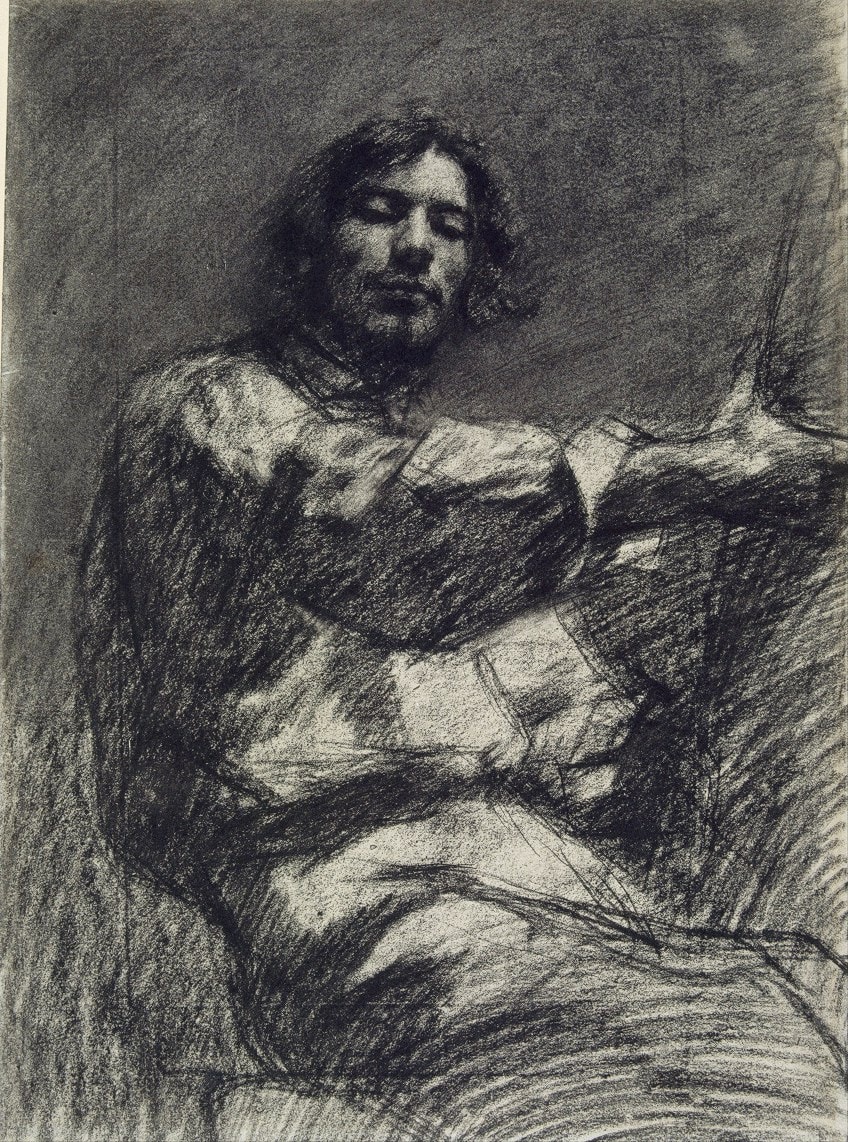

Courbet came to Paris when he was 21 years old. He avoided studying in the workshops of any of the period’s numerous academic luminaries, and he did not enroll in Paris’s leading artistic academic institution, the École des Beaux-Arts. Rather, he took a few classes from lesser-known professors, but largely trained himself by imitating paintings in the Louvre by Rubens, Caravaggio, and others. During a trip to Holland, he was also able to replicate Velazquez’s and Rembrandt’s works.

While Academy pupils had to wait up to a year to take up a brush (drawing instruction came first), Courbet set his own demanding timetable and dove headfirst into painting.

He frequently recreated a traditional picture in order to discover its mysteries. He completed his solo studies by painting from the outdoors and with hired models. He depicted family and friends while visiting his family in Ornans. Courbet likewise immersed himself in his own Realism, rejecting any traditional approach or vocabulary.

Despite the fact that this was rather unconventional at the time, he was still concentrated on being chosen for the formal French Salons. However, just three of his 25 entries were approved during his first seven years in Paris.

Mature Period

During his tenure in Paris, Courbet produced in a constant Realist style. For instance, he turned down a commission to create angels for a chapel, saying, “Show me an angel, and I will create one.” Instead, he portrayed ordinary people in all their wonderful banality, and it was no shock when Courbet’s increasing circle of important allies made him head of the Realist organization in Paris in 1848.

Both the writer Charles Baudelaire and the vocal revolutionary Pierre Proudhon were members of this circle of academics who challenged each other to question the accepted standards of the day. In 1848, the Paris Salon turned jury-free for a year under a recently created Republic. This permitted Courbet’s entry of 10 works to be accepted automatically, where they made an excellent impact and helped the painter earn a gold medal the subsequent year.

According to academy norms, the gold medal granted Courbet immunity from subsequent selection committees, a benefit he retained until 1857 when the policy was altered. Burial at Ornans (1849-1850), among other great works, would almost certainly have been dismissed if not for this safeguard. Courbet’s most brazen show of country Realism was this massive provocative artwork.

The large scale at which he showed ordinary people drew a hailstorm of criticism, with many traditionalist opponents uneasy with the image’s apparent endorsement for democratic governance.

Paradoxically, the French government resorted to an authoritative Empire under Napoleon III soon after the premiere of Burial at Ornans. Courbet remained adamantly hostile to his reign, and the ruler would eventually have reason to disapprove of Courbet’s nakedness.

Napoleon III and his wife Eugenie made one of the most remarkable disapproving actions in 1853: the story says that while browsing the Paris Salon, Eugenie made a statement of praise for Rosa Bonheur’s work, The Horse Fair, which depicted gigantic workhorses from behind.

Soon afterward, standing in front of Courbet’s work The Bathers (1853), which depicts two strong farm ladies bathing in a river, she observed that Courbet’s subjects resembled the massive Bonheur horses – then, allegedly, the emperor hit the painting with his equestrian crop. When three of the 14 canvases Courbet presented to the committee of the Paris World Exposition in 1855 were dismissed, the artist devised a business model that was as stunning and original as his works.

He stubbornly built his own pavilion outside of the grounds, dubbed “Realism,” and showcased 40 paintings spanning his 15-year career.

Late Period

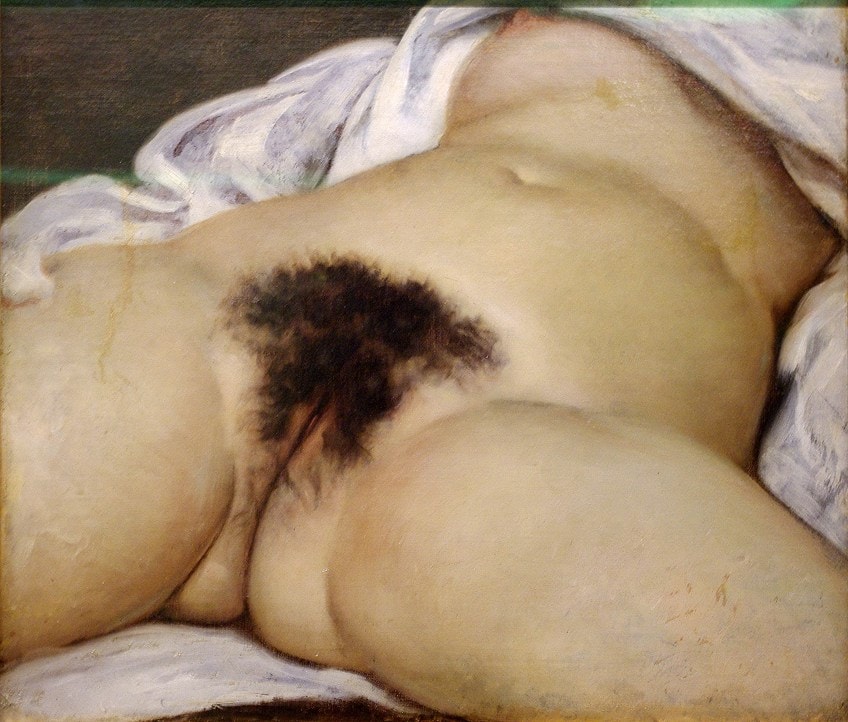

Courbet concentrated on sexual nudes, hunting scenarios, panoramas, and seascapes throughout the 1860s. In this piece, he defied Academic Classicism, even more, promoting his new perspective and inspiring other modernists. Courbet’s liquid is raw and palpable, with thick paint on a surface that shouts nearly as loudly as the impression of water itself.

The French Realist painter’s nudes from this era violated the standards of the time and, in certain cases, remain controversial to this day.

Origin of the World (1866), the most famous, depicts a woman’s lower torso and exposed thighs. The classic artifice is eliminated, forcing the viewer to focus on the most personal aspect of women’s bodies; Courbet instructs the observer exactly where to look, implying that such graphic realism should be accepted. This candid depiction of the naked foreshadowed the visceral sexuality of early-20th-century artists like Egon Schiele.

Courbet was despised by the French Academy and other governmental organizations for most of his career. However, in 1870, he was granted the Legion d’Honneur, the highest French decoration of distinction, which he declined.

Courbet, in typical rebellious flair, wrote an open letter in which he claimed: “Honor is not found in a title or a ribbon; it is found in acts and the intentions behind those actions. The majority of it is based on respect for oneself and one’s opinions. I honor myself by adhering to my lifetime convictions.”

Gustave Courbet never married, arguing that his work didn’t give him enough time to settle down. In 1872, he proposed to a very young lady, claiming in a letter that if she accepted, she would be coveted across France and even “reborn three times without ever stumbling across a situation like this one.” However, the woman declined, and Courbet remained a bachelor for the rest of his life.

Final Years

Courbet was chosen head of the Republican Arts Commission in the short-lived Paris Commune when the French Empire was eventually defeated in the Franco-Prussian war. The Place Vendôme Column, built by Napoleon I from the bronze of opposing cannons, was demolished while he was in charge.

Courbet’s exact participation in the column’s demolition is unknown, and it’s conceivable that he just planned to relocate it. Nonetheless, the column’s demise resulted in his demise too. When the new Group failed rapidly, Courbet was sentenced to six months in prison in 1871, spending the latter part of his sentence in a health center due to illness.

This catastrophe was followed by another when he was obliged to directly pay 300,000 francs for the installation of a new Vendôme Column in 1873. Faced with this unfathomable debt, he fled into self-imposed seclusion in Switzerland. He kept painting, but he never returned back to France.

He died in 1877, at the age of 58, of severe drinking and liver illness at La Tour-de-Pails, Switzerland. His ashes are presently interred at the Ornans Cemetery. Gustave Courbet’s Realism may be regarded as part of a larger investigation into the physical universe that captivated academia in the 19th century. But it was his disdain for the French Academy’s strictures that motivated him the most in Gustave Courbet’s paintings.

Unlike other French painters of that period, Gustave Courbet’s artworks disregarded Classical or Romantic approaches in favor of taking lowly images of country life – themes normally associated with small genre painting – and transforming them into material for grand historical painting.

The Legacy and Style of Gustave Courbet

The democratic eye of Gustave Courbet changed Western art. His new Realism set the door for later Modern styles like Impressionism and Post-Impressionism. Courbet had close touch with Monet, Manet, Renoir, and others, who were strongly influenced by the man and his works. Courbet’s expressive paint application also paved the way for 20th-century figures and landscape painters such as Fairfield Porter, Willem de Kooning, Lucian Freud, and others. Courbet momentarily gave up painting to work in government during the Paris Commune of 1871. This was typical of his left-wing sympathies.

His art was not openly political, but in the circumstances of the period, he was not dismissed because he communicated notions of justice by making heroes of ordinary people, painting them in large size, and failing to hide their flaws.

Courbet frequently opted on compositions that appeared collaged and primitive to conventional tastes while wiping away the jargon of Academy painting. He also abandoned precise modeling at times in favor of generously applying paint in fragmented flecks and slabs. Such artistic developments earned him the admiration of succeeding modernists who advocated for unfettered compositions and enhanced surface texture.

Rather than relying only on the state-run Salon system, Courbet innovated the solo exhibition as a private economic business, a strategy that many later renegade artists adopted.

Gustave Courbet’s Artworks

Courbet’s Realism may be seen as part of a larger investigation into the physical universe that captivated scientists in the 19th century. But it was his dislike for the French Academy’s strictures that motivated him the most in his own field of painting. Rather than using Traditional or Romantic treatments, he used lowly images of village life – themes that are normally associated with small genre painting – to create magnificent history paintings. He became well-known as a result of this.

Here are a few exemplars of Gustave Courbet’s paintings.

Burial at Ornans (1849)

| Date Completed | 1849 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 315 cm × 660 cm |

| Current Location | Musée d’Orsay, Paris |

This picture at the Musee d’Orsay’s main chamber engulfs the observer as if he or she were in a cave. Figures wander around in the dark, fixated on formality, in a very non-classical composition. The picture, which is a good example of Realism, keeps to the facts of a genuine funeral and avoids exaggerated spiritual overtones.

Courbet purposefully did not allow the light in the painting to reflect the eternal, emphasizing the transient element of existence.

While sunset may have represented the soul’s grand movement from the transitory to the eternal, Courbet obscured the evening sky with clouds, making the change from day to night a simple repetition of the coffin’s transition from light to darkness. Some critics perceived the commitment to precise realities of death as disrespect to religion and attacked it as a shoddily constructed building with worn-faced working-class citizens elevated up to life-size in a massive work as if they must have some kind of glorious worth.

Other reviewers admired the painting’s inference of fairness and goodness in all individuals and saw how it could help change the trajectory of Western art and ideology.

The Bathers (c. 1853)

| Date Completed | c. 1853 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 227 cm x 193 cm |

| Current Location | Musée Fabre, Montpellier |

In The Bathers, a fairly large woman is seen from behind exiting a little pool, nude save for a thin cloth covering her lower buttocks. She motions to her maid, who is seated on the ground removing her shoes and stockings. The maid is staring at the woman, but it is uncertain what they are thinking or saying to one another. People opposed it because it was nasty and meaningless.

The nudists in these paintings were invariably elegant, classical figures.

The nudity in The Bathers is a more realistic, and consequently cruder, portrayal of the female body. Furthermore, the typical topic of a naked bather with her clothed friend was popular at the period, although there was always some form of the biblical or mythical tale being communicated. Courbet’s picture was devoid of any story. The picture sparked a lot of debate as soon as it was displayed. Because he had won a medal in 1848 and was excluded from the selection procedure, the Salon was obligated to accept the picture.

The thin veil concealing the bather’s lower bottom appears to be an effort by Courbet to avoid criticism since it appears to have been painted on after the fact. The picture was dubbed “dirt” and was denounced as subversive.

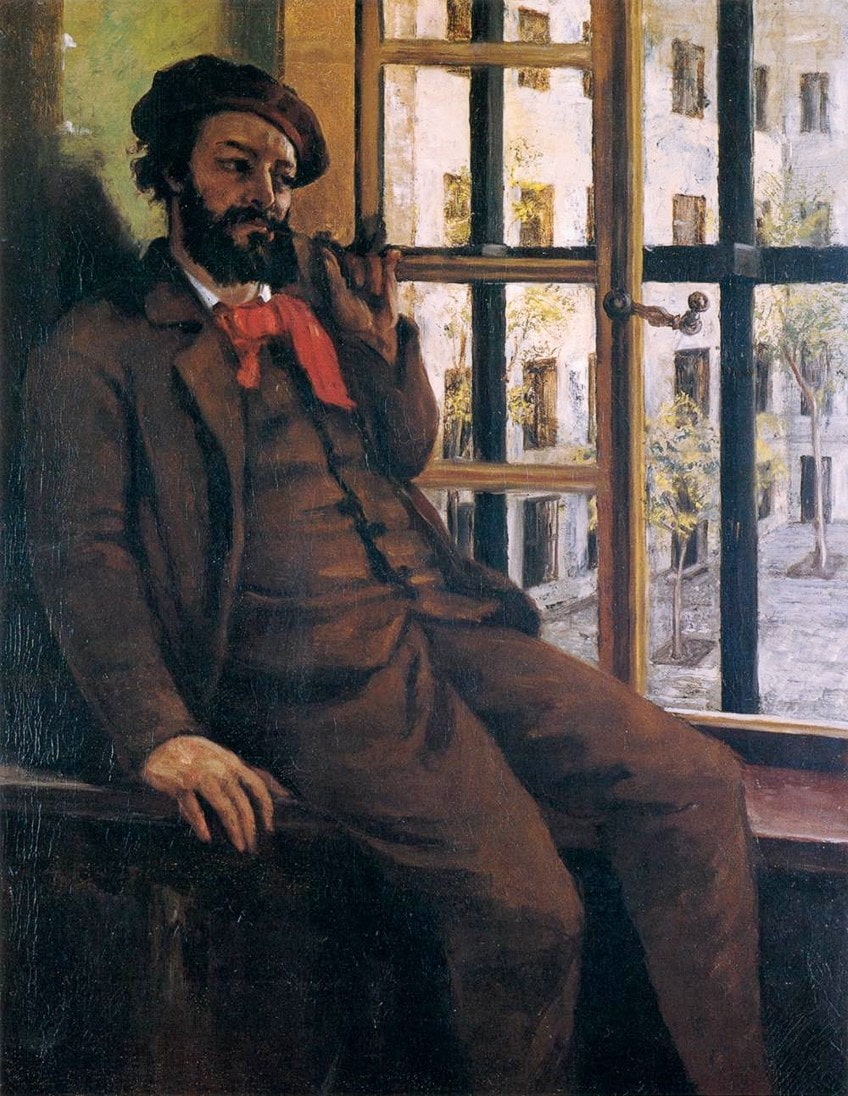

The Meeting (1854)

| Date Completed | 1854 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 129 cm x 149 cm |

| Current Location | Musée Fabre, Montpellier |

Courbet depicted himself meeting Alfred Bruyas, an important benefactor and supporter, in this enormous piece. The picture displays the collector’s admiration for Courbet’s talent. The maid is captured in the greatest show of respect as an appendage of Bruyas, but the main point is this moment of reciprocal admiration between artist and client.

Courbet’s head is slightly cocked back as a sign of high knowledge and significance, and he is the only one standing right in unfiltered light. Courbet’s sense of self-importance shows through in this work at the same time. His beard, as if in judgment, points towards the patron.

The artist also holds a staff that is double the size of the one that his customer uses to support himself – another allusion to the artist’s power.

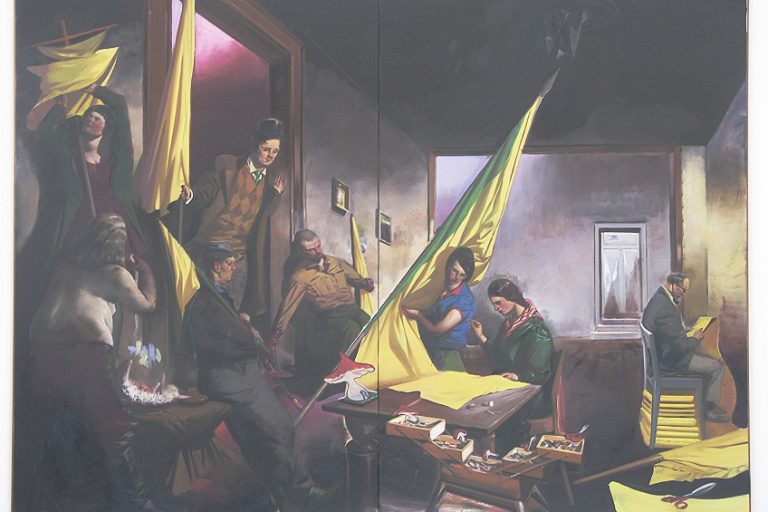

The Painter’s Studio (1855)

| Date Completed | 1855 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 361 cm x 598 cm |

| Current Location | Musée d’Orsay, Paris |

Courbet’s 19-foot-long painting expresses his self-esteem and satisfaction in his iron determination, hard effort, and revolutionary intellect. In this piece, he makes a hero of himself in the same way as he heroized others in the Burial at Ornans.

Courbet explains, with a healthy dose of egotism, that when individuals think for themselves and confront the current quo, things get done and attitudes change.

Courbet enlarges himself, brush in hand, to start on a landscape painting. Courbet’s colleagues on the right represent kindred spirits and invention, while the admiring youngster expresses Courbet’s belief that his legacy would last for decades. The naked figure standing behind the painter validates both his excellence and her status as muse. Courbet’s acknowledgment of the working poor’s entitlement to be included may be seen on the left. Napoleon III, his enemy, is shown as a poacher with a weapon and his hounds.

In a representation of the innovator triumphing over the authoritarian, Courbet’s chin-up stare triumphs over Napoleon’s downward inclined head.

The Wave (1869-1870)

| Date Completed | 1869-1870 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 170 cm x 160 cm |

| Current Location | The Oskar Reinhart Collection, Winterthur |

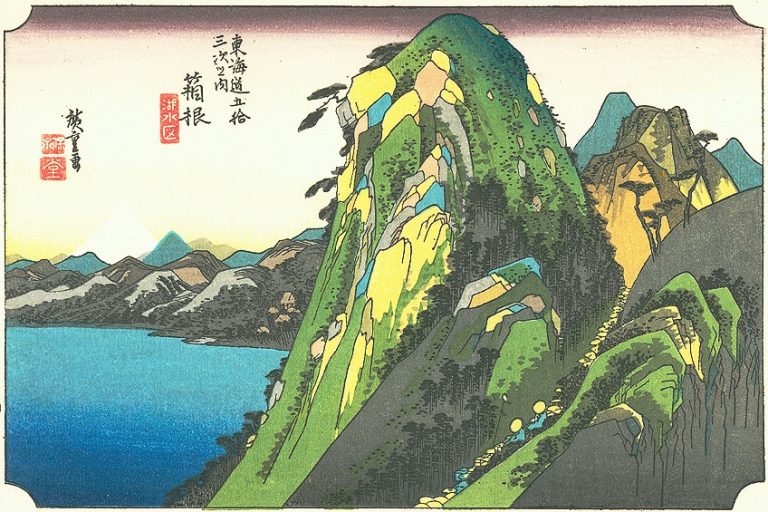

Several early Modernists were inspired by Japanese prints, and some say that Courbet was among the first to be influenced by this Eastern style. Drawing inspiration from the prints, he most likely depicts a piece of water cut off from the vision of immense space. The work exemplifies Courbet’s landscapes and seascapes, which were usually made up of fragmented patches of paint laden in both dark and bright places. The young Impressionists were inspired by such painterly techniques.

Courbet’s obvious application of thick paint, most of which he aggressively spread on the canvas with a palette knife to produce the feeling of flowing water and foam, immerses the observer in seething waves.

Recommended Reading

Would you like to learn more about Gustave Courbet’s artworks? Or perhaps you would like to get someone an art-related gift. Here is a list of books that we can suggest regarding French Realist painter Courbet.

Letters of Gustave Courbet (1992) by Gustave Courbet

Gustave Courbet, a vital player in the development of modern painting, remains a painter whose activities, beliefs, and friendships are poorly understood. Courbet, a prolific correspondent, provides a tantalizing path for a more in-depth appraisal of his character and accomplishments through his letters. Petra ten-Doesschate Chu’s critical edition of over 600 of the artist’s letters provides just such a glimpse into the artist’s inner life; her unprecedented accomplishment of assembling together all of Courbet’s known letters, many of which were previously unpublished and untranslated, is certain to alter our perception of Courbet’s originality and his position in 19th century French life.

- A critical edition of over 600 of the artist's letters

- These letters offer numerous insights into Courbet's life and art

- Correspondence enables readers to follow the artist's development

Gustave Courbet (2007) by Manuel Jover

Courbet was a creator of figurative paintings, landscapes, and seascapes best regarded as a pioneer in Realism. He also dealt with social themes, such as peasants and the harsh workplace circumstances of the poor. His work was not associated with the major Romantic or Neoclassical traditions. Courbet thought that the purpose of the Realist artist was to seek the truth.

- A look at Gustave Courbet, one of the top innovators of Realism

- The artist also worked with social issues and addressed peasantry

- Neither Romantic nor Neoclassical, Courbet aimed to depict the truth

Gustave Courbet is recognized as a major player in the emergence of Realism in the mid-19 century. Gustave Courbet’s paintings, which disregarded the Academy’s French artists’ classical and dramatic traditions, stressed the physical reality of what he saw – even if that truth was plain and faulty. As a devoted Republican, the French realism painter saw his art as a vehicle to campaign for the farmers and rural residents of his region. Historians increasingly see Gustave Courbet’s paintings as a crucial forerunner to other early modernist artists like Claude Monet and Édouard Manet.

Take a look at our Gustave Courbet paintings webstory here!

Frequently Asked Questions

Who Was Gustave Courbet?

Realism by Gustave Courbet was part of greater research into the physical cosmos that fascinated academia in the 19th century. In Gustave Courbet’s paintings, however, it was his contempt for the French Academy’s rules that drove him the most. Gustave Courbet’s paintings, unlike those of other French painters of the time, eschewed Classical and Romantic techniques in favor of translating lowly pictures of country life – topics generally associated with tiny genre painting – into material for big historical painting.

Why Was Gustave Courbet Important?

His art was not overtly political, but given the conditions of the time, he was not dismissed for portraying regular people as heroes, painting them on a big scale, and failing to disguise their shortcomings. Courbet regularly chose compositions that seemed collaged and primal to traditional sensibilities, while eschewing Academy painting language. He also strayed from accurate modeling at times, opting instead for a liberal application of paint in broken specks and slabs.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Gustave Courbet – Artistic Biography of This French Realist Painter.” Art in Context. March 14, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/gustave-courbet/

Meyer, I. (2022, 14 March). Gustave Courbet – Artistic Biography of This French Realist Painter. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/gustave-courbet/

Meyer, Isabella. “Gustave Courbet – Artistic Biography of This French Realist Painter.” Art in Context, March 14, 2022. https://artincontext.org/gustave-courbet/.