French Impressionism – Its History and Characteristics

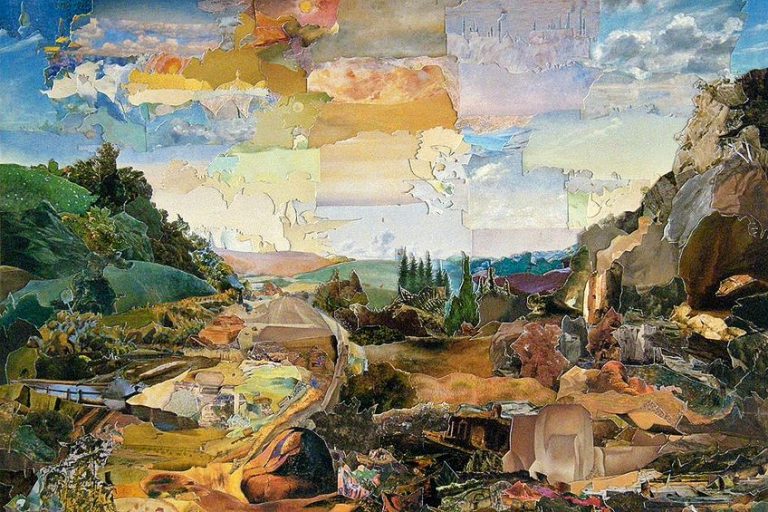

French Impressionism art was the first modern artistic style to produce significant masterpieces inspired by real life. This was a revolutionary art movement that emerged in the late 1800s and was led by numerous well-known French impressionist painters. French Impressionist artists rejected classical subject matter in favor of modernity, seeking to produce works that represented their current circumstances and environments. This article will explore the history of French Impressionist paintings and the artists who created them.

Table of Contents

The History of French Impressionism Art

Despite its status as a ground-breaking movement, Impressionism can trace its origins to earlier painting forms such as Naturalism and Realism, which were already questioning conventional views of aesthetic beauty and the artist’s connection with the state. In the mid-19th century, the Realism movement was the first to challenge the established Parisian art hierarchy.

In the mid-19th century, the Realism movement was the first to challenge the established Parisian art hierarchy.

Realism was promoted by Gustave Courbet, who was an anarchist that believed that his era’s art closed its eyes to life’s realities.

Challenging Academic Art

The French were governed by a repressive regime, and the majority of the citizens were impoverished. Rather than portraying such scenarios, artists of the time focused on idealistic nudity, historical and mythological storytelling, and portrayals of nature. Gustave Courbet funded an exhibit of his work directly across the street the Universal Exposition in Paris in 1855 as a demonstration, a daring effort that inspired other artists who wished to disrupt the status quo.

Simultaneously, the rise of Naturalism, a movement strongly connected to Realism, demonstrated how art may use the natural world as its subject matter without disguising it in the frameworks of historical or mythical heroes.

Ever since the 1820s, artists such as Jean-François Millet and Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot had been visiting the Barbizon Forest south of Paris to study the trees, landscape, and rural working classes en plein air (painting outdoors).

The Barbizon School’s birth signaled the beginning of a worldwide shift in painting toward presenting the nature of reality in all of its unadorned beauty and glorifying the lives of rural laborers.

While Naturalism differs from Impressionism in its recurring emphasis on hyperreal detail, the Impressionists’ appreciation of the natural world, as well as their use of plein-air painting, derives much from the earlier Naturalist ideology.

The Establishment of the Salon des Refusés

A considerable number of painters were barred from participating in the annual art salon, the most prominent event of the art world in France, in 1863, causing popular outrage.

In response, the Salon des Refusés was established the same year to facilitate the presentation of artworks by artists who had been denied entry to the official salon.

Camille Pissarro, Paul Cézanne, James Whistler, and Édouard Manet were among the painters on display. Although Emperor Napoleon III sanctioned it in order to appease the artists associated, the 1863 art show was extremely contentious with the public, owing primarily to the unorthodox topics and styles of artworks such as Le déjeuner sur l’herbe (1863) by Manet, which depicted nude women and clothed men having a midday picnic.

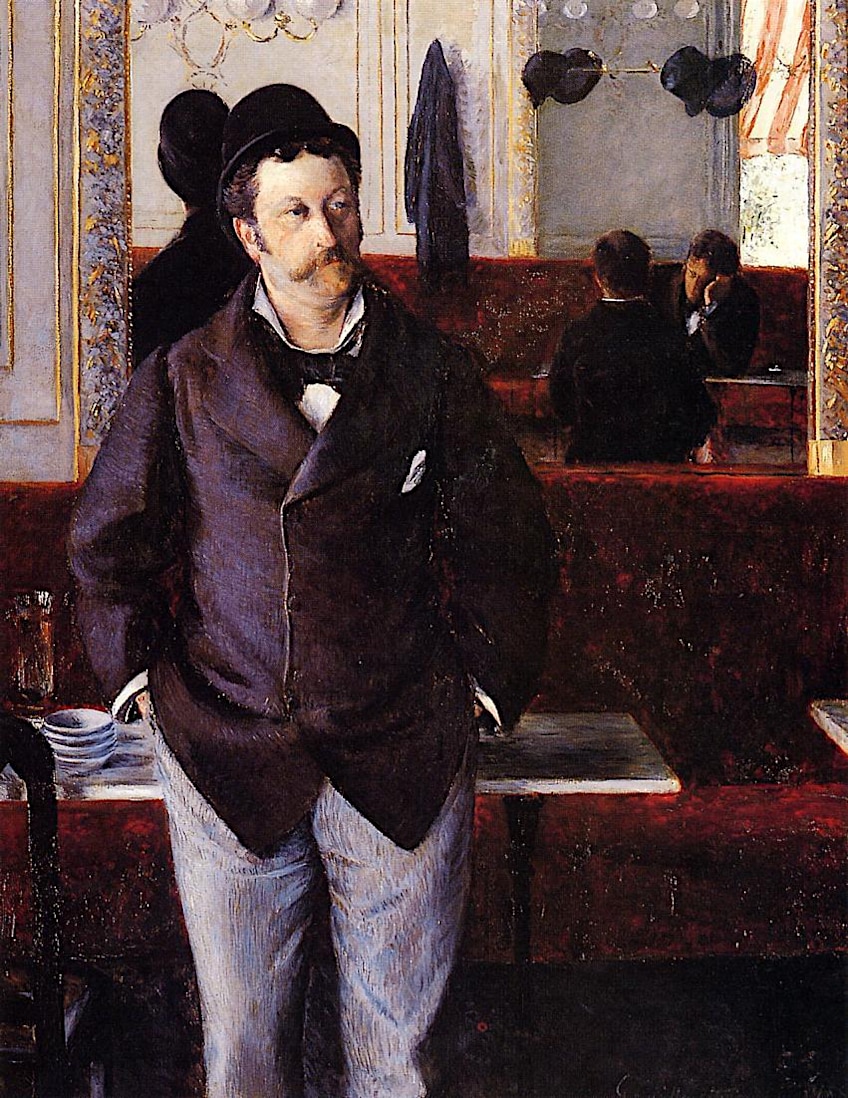

Édouard Manet was one of the first and most significant innovators to appear in the Paris public exhibition scene. Although he grew up admiring the Old Masters, in the early 1860s he started to adopt an inventive, free painting style and livelier palette. He also began to concentrate on depictions of ordinary life, such as images from cafés, streets, and boudoirs.

Manet’s anti-academic approach and distinctly modern themes quickly drew the attention of artists on the periphery and inspired a new sort of painting that deviated from the standards of the period.

French Café Society

Parisian cafés were among the most popular places for the painters of the emerging French Impressionism art movement to congregate and converse. Manet frequently visited Café Guerbois in Montmartre beginning in 1866. The cafe was frequented by Alfred Sisley, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Claude Monet, Edgar Degas, Paul Cézanne, and Camille Pissarro, while Bazille and Caillebotte had workshops nearby and frequently joined the gatherings.

Other individuals, such as critics, authors, and photographers, were particularly drawn to this group.

The group was interested in a diverse range of individuals, economic realities, and political viewpoints. Renoir, Monet, and Pissarro were from merchant families or working-class origins, whilst Caillebotte, Morisot, and Degas were from upper-class families. Alfred Sisley was Anglo-French, while Mary Cassatt was American. This mix of personalities may have contributed to the group’s high level of inventiveness.

The Exhibition of French Impressionist Paintings

Although they weren’t yet united by a specific style, the group chose to establish a commercial cooperative because they were tired of the oppressive academic requirements of fine art. In general, the French Impressionist painters’ financial success was modest, and only a handful of their paintings were approved for salon shows in Paris, thus the business was crucial in determining their economic security and creative freedom.

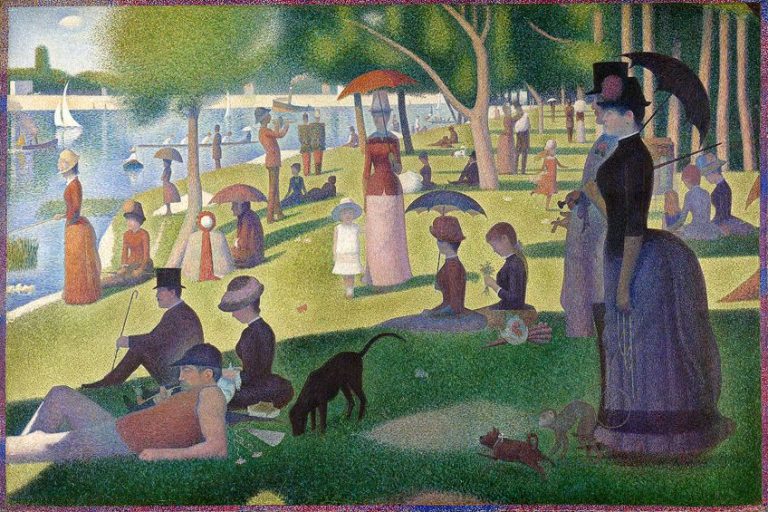

They hosted the first of a number of shows in photographer Felix Nadar’s studio in 1874. They didn’t start calling themselves The Impressionists until the third show in 1877. While their initial exhibition gained little public notice, and the majority of the eight exhibits they staged cost money instead of generating money for the collective, their following displays drew large crowds, with attendance numbers in the thousands.

Despite this attention, most of the French Impressionist artists sold very few pieces, and some of them stayed impoverished throughout the period.

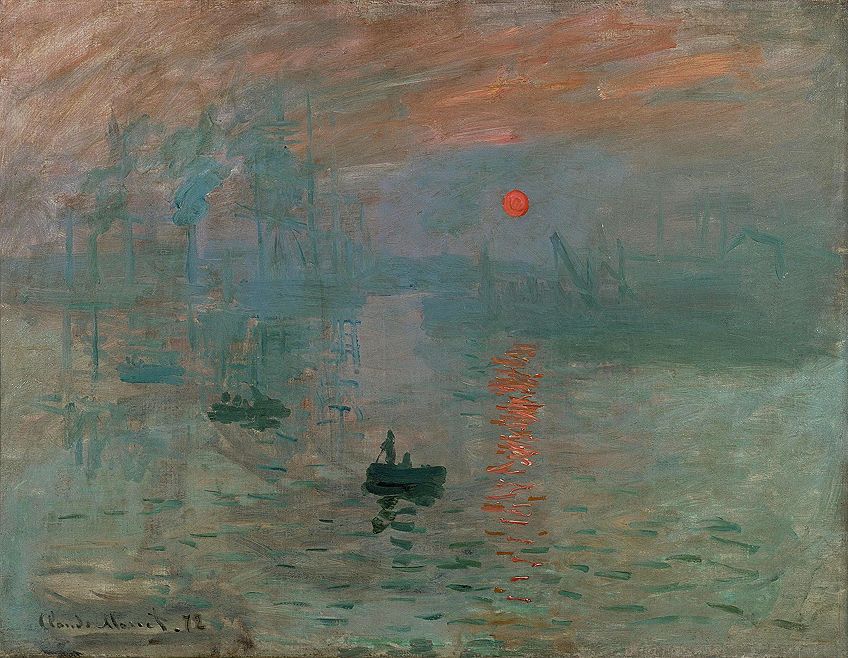

The Naming of the Movement

The movement was named after Louis Leroy, who used the title of Claude Monet’s work Impression, Sunrise (1873) in his scathing criticism of the inaugural Impressionist exhibition in 1874.

The critic lambasted the movement for only painting impressions. The French Impressionist artists decided to embrace the name.

However, in subsequent decades they also started referring to the movements as the “Independents,” which referred to the provocative concepts of the Société des Artistes Indépendants, which was founded in 1884 by French Impressionist painters who wanted to break away from traditional artistic norms. Although the Impressionists’ approaches differed significantly, and not all of the French Impressionism painters would accept Leroy’s term, they were united by a shared interest in the expression of visual perception, focused on brief optical perceptions, and a concentration on fleeting aspects of modern life.

Later Developments

Even though the French Impressionist artists were a diverse bunch, they met on a regular basis to discuss and display their works. Between 1874 and 1886, the group worked on eight exhibits, but they were gradually dissolving as a collective. Many believed they had perfected the early, exploratory styles that had earned them recognition and sought to branch out into new areas of innovation. Others, concerned by their work’s continuous commercial failure, shifted stylistically with the goal of generating more sales and attention.

Paul Durand-Ruel, a French art trader who was based in London, was mainly responsible for the Impressionist movement’s eventual adoption.

In 1871, Monet encountered Durand-Ruel, who bought French Impressionist paintings and displayed them in London for many years. Sales were modest at first, but commencing in the late 1880s, he began presenting French Impressionism art in the United States, with increasing success. Durand-Ruel proved that he could captivate an audience of American buyers who subsequently acquired more Impressionist pieces than were ever sold in France over the next few years, after exhibiting in Philadelphia, New York, and Chicago. Prices for French Impressionism art increased, making Monet a fortune.

By this stage, Impressionism was so close to becoming an academic norm that a large group of American artists converged on Monet’s home in Giverny to learn from the group’s head.

The Characteristics of French Impression Art

Color became a prominent priority for Impressionist painters as well. They favored vivid, clear hues that seemed to leap off the panel and hit the observer with their energy.

Vivid greens, blues, and yellows were popular among Impressionists.

They also loved experimenting with new synthetic hues such as cerulean blue and ultramarine, and they seldom blended paints together, which tended to dilute the strength of the colors. Rather, they preferred to let colors merge in the audience’s sight. A few other characteristics are:

- Brush strokes that are bold

- Shorter and thicker strokes of brilliant color

- There is no use for black

- Photography’s influence

- Painting outside

- Influence of Japanese prints

The Depiction of People in French Impressionism Art

Other Impressionists, such as Edgar Degas, were less interested in painting outside and opposed the notion that art should be an act of spontaneity. Degas loved indoor images of daily life: individuals lounging in cafés, performers in an orchestra pit, ballet dancers executing routine warmups at rehearsal. He also used stronger lines and heavier brushstrokes to characterize his forms more clearly than Camille Pissarro and Claude Monet.

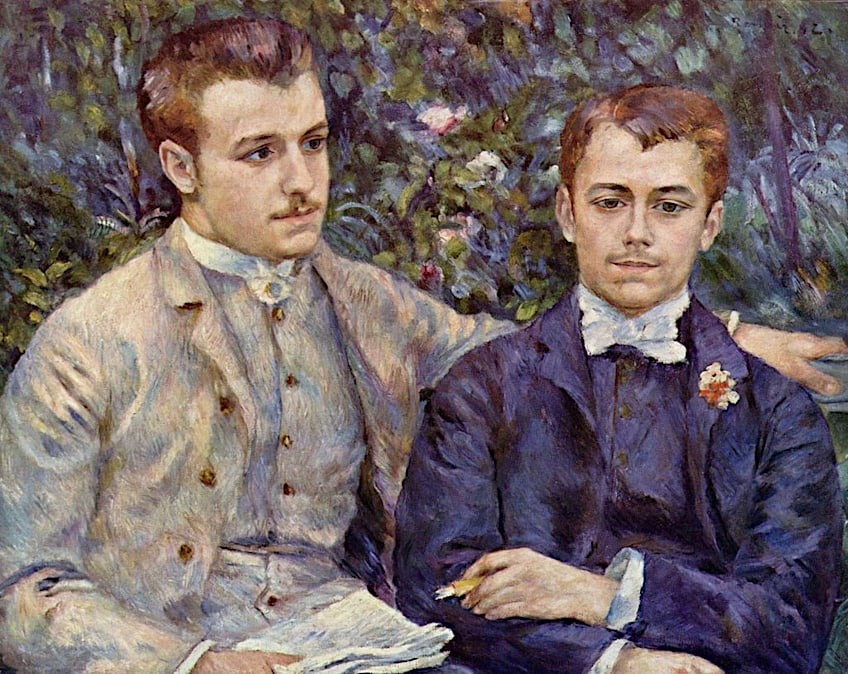

Other artists, such as Berthe Morisot, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and Mary Cassatt, were interested in the human form as well as the psychological state of the individual.

Renoir, famed for his use of brilliant, saturated colors, represented the daily routines of residents from his Montmartre region, specifically the social activities of French society.

Although Renoir, like Cassatt and Morisot, worked outdoors, he focused on the facial features and emotional elements of his figures instead of the atmospheric circumstances of the environment, highlighting the human figure with loose and light brushwork.

Cityscapes in French Impressionism Art

Impressionism was heavily impacted by Baron Georges-Eugène Haussmann’s reconstruction of Paris in the 1860s because the movement was profoundly ingrained within Parisian society.

This urban project, also known as “Haussmannization,” intended to modernize the city by constructing vast boulevards that became centers of public interaction.

This urban redevelopment also gave rise to the concept of the flâneur: the drifter who roams the city’s public places, witnessing life while staying isolated from the population.

In many French Impressionist paintings, the drifter’s detachment is closely related to modernity and the individual’s separation from the city.

These urban subjects are portrayed in the works of Gustave Caillebotte, a latter advocate of the Impressionist style who concentrated on panoramic vistas of cities and the psychology of their inhabitants.

Caillebotte’s paintings, such as Paris, Rainy Day (1877), represent the artist’s response to the shifting nature of society, depicting a drifter in his typical black coat and top hat wandering through the open space of the street while glancing at passersby.

Influences on the Movement

There were a few notable influences on the movement that would be worth mentioning. One of these influences was photography, which was offering artists new ways of imagining how moments should be captured. Another influence was Monet’s preference of painting outside. Let’s explore these two influences further.

The Influence of Photography on French Impressionism Art

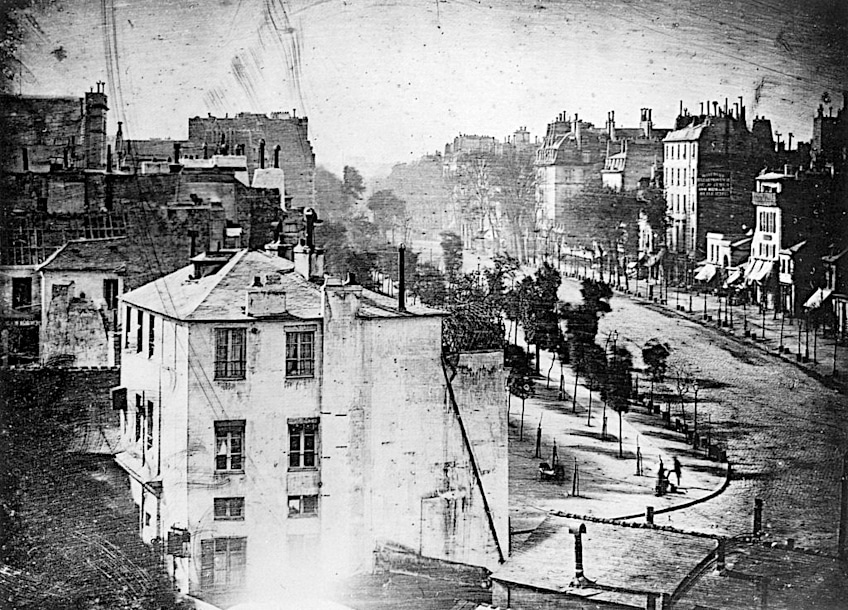

French Impressionism art was influenced by photography. The history of this medium is complicated and international, but one pivotal event was the introduction of the Daguerreotype by Louis Daguerre, the French inventor in Paris in 1839.

Daguerre invented a method for transferring images of the world onto a sheet of copper coated with silver that reacted to light.

This enabled a direct impression of reality to be captured on a two-dimensional surface, revolutionizing people’s abilities to effectively record the environment and their own lives. By 1849, 100,000 Parisians were being photographed each year.

The impact of photography on Impressionism was essentially multifaceted. On the one hand, it changed people’s ideas about what was worthy of visual reconstruction. In France, academic painting has typically centered on mythological and historical subjects, as well as portraits of national heroes and leaders.

Photography enabled the preservation of all types of individuals, settings, architecture, and landscapes in visual form, even what those forms looked like in motion.

This, in turn, influenced certain French Impressionist painters’ perceptions of who and what deserved their attention; the café scenes, side alleyways, and crowded squares of French Impressionist paintings represent not just a dynamic urban realm, but also a newly discovered sense that this world was worth preserving.

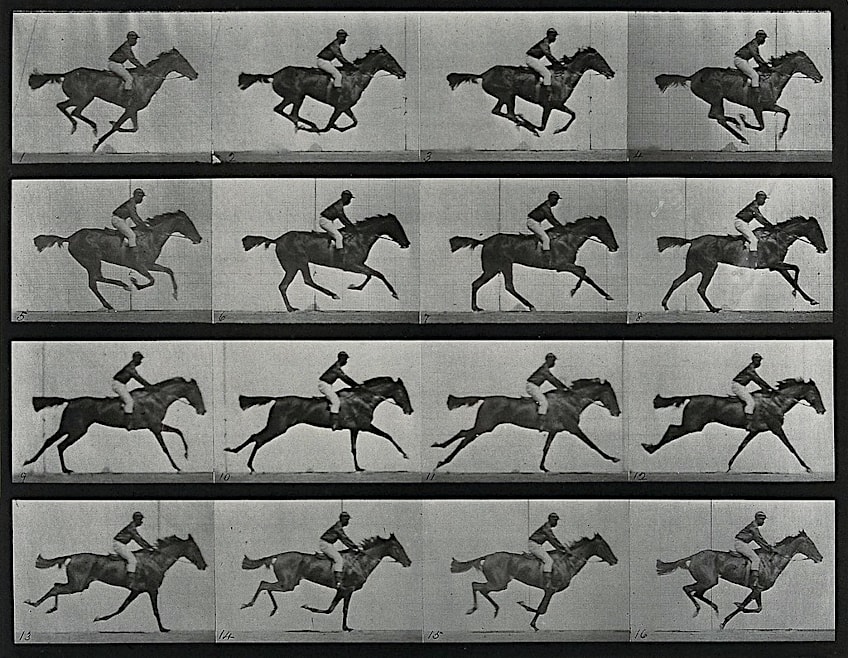

A Galloping Horse and Rider by Eadweard Muybridge (1878); See page for author, CC BY 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

On the other hand, it also introduced artists to the concept of spontaneous composition, as well as the associated feeling that a photograph might depict both a moment and location. A work like Degas’ Place de la Concorde is less of a depiction of a Parisian public place as it is a representation of that plaza and the individuals and animals that were actually crossing over it at that very moment.

The chaotic grouping of figures in motion in this and numerous other French Impressionist paintings may only have been acquired by interaction with a device capable of freezing and graphically conveying a millisecond of time.

Claude Monet’s Plein-Air Influence

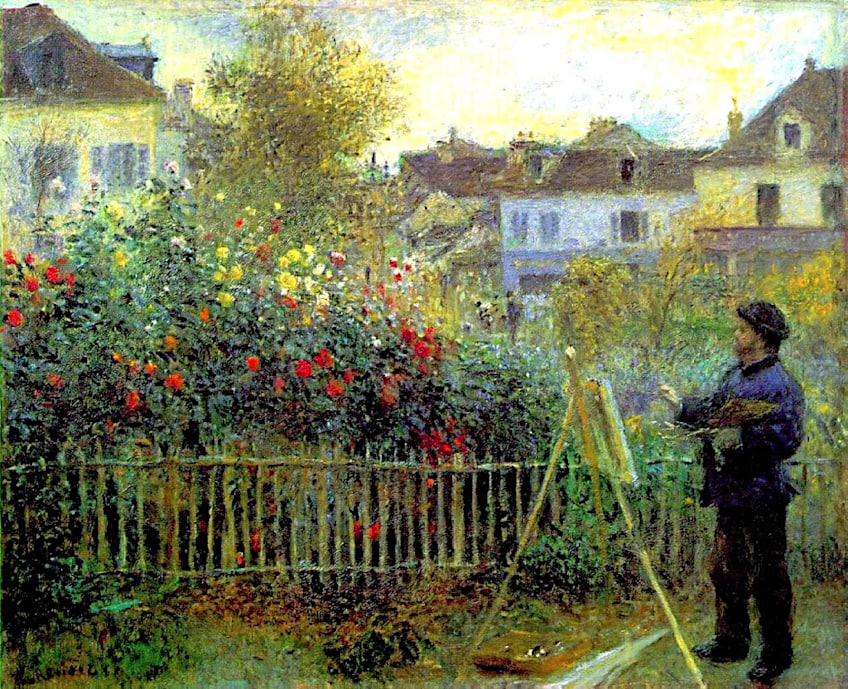

Claude Monet is possibly the most well-known Impressionist. He was known for his command of natural light and produced several times of day to depict changing situations.

He used very gentle brushstrokes and did not mix colors to create a slight sense of movement, as if nature itself was alive on the surface.

He did not allow the paint to dry between layers, resulting in softer edges and indistinct boundaries that implied three-dimensional planes rather than representing them accurately. Monet was known for his love of outdoor painting, or plein-air painting.

Monet’s outdoor painting style was widely used by French Impressionist artists. This method, acquired from the Barbizon School of artists, led to improvements in the depiction of sunshine and the progression of time, two essential themes of French Impressionist paintings. While Monet is regarded as the most important figure in the tradition of outdoor painting, Camille Pissarro, Berthe Morisot, Alfred Sisley, John Singer Sargent, and many others worked outside, articulately depicting the ephemeral nature of the outside world.

The Top Impressionist Artists

There were many artists in France who took to the style. However, there are several names that really stick out from the crowd. Men and women, though, tended to focus on varying subjects. Women tended to focus on domestic settings, unlike the preference of the males for more public venues.

Male French Impressionist Artists

Monet started the tradition among Impressionists to paint outside, and most men of the time followed in the same fashion. These included Alfred Sisley, John Singer Sargent, and several others. Artists such as Edgar Degas, Pierre Auguste Renoir, and Édouard Manet helped set the high standards of the movement, forever shifting the paradigm of art.

Camille Pissarro is regarded as one of the most significant people within the movement, and is often referred to as the “Father of Impressionism”.

Female French Impressionist Artists

Unlike the male Impressionists, who painted figures mostly in public settings, Berthe Morisot focused on the intimate lives of women in late-19th-century society. The Impressionists’ first female exhibitor, she created lush compositions that showcase the domestic, intensely personal domain of feminine society, typically highlighting the maternal link between parent and child, as in The Cradle (1872).

Morisot is regarded as one of the major female artists of the French Impressionist movement, along with Mary Cassatt and Marie Bracquemond.

Cassatt was an artist from the United States who traveled to Paris in 1866 and started exhibiting with the French Impressionists in 1879. She portrayed women in the domestic sphere of the house, but also in the public settings of the newly urbanized city, as in her opus At the Opera (1879). Her paintings contain a variety of breakthroughs, such as the flatness of three-dimensional space and the use of brilliant, even gaudy colors, both of which foreshadowed later advances in modern art.

The French Impressionist painters employed brighter colors and looser brushstrokes than preceding artists. They challenged the conventional three-dimensional viewpoints and the purity of form that had traditionally served to identify the more significant aspects of an image from the less significant ones. As a result, several critics attacked French Impressionist paintings for their incomplete look and amateur quality. Taking up Gustave Courbet’s theories, the Impressionists intended to be artists of the real: they wanted to broaden the range of possible topics for artworks. Moving away from idealistic shapes and perfect symmetry, they focused on the world around them as they perceived it, which was flawed in a variety of ways.

Take a look at our French Impressionism Art webstory here!

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is French Impressionism Art?

French Impressionism art is possibly the most influential trend in modern painting. A collection of young painters chose to depict what they saw, felt, and thought at a certain point in the 1860s. They were not concerned with depicting history, myths, or the lifestyles of famous men, and they were not concerned with artistic perfection.

What Are the Characteristics of French Impressionism Art?

The French Impressionist painters attempted to capture on canvas an impression of how a scene, object, or personality seemed to them at a given time. This frequently meant employing considerably looser and lighter brushwork than artists had used up to that point, as well as painting outside, a technique known as en plein air. The French Impressionist artists also refused official exhibits and painting competitions organized by the French government, instead creating their alternative group exhibitions, which were originally met with hostility from the public. All of these movements foreshadowed the birth of modern art and the related avant-garde ideology.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “French Impressionism – Its History and Characteristics.” Art in Context. January 12, 2023. URL: https://artincontext.org/french-impressionism/

Meyer, I. (2023, 12 January). French Impressionism – Its History and Characteristics. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/french-impressionism/

Meyer, Isabella. “French Impressionism – Its History and Characteristics.” Art in Context, January 12, 2023. https://artincontext.org/french-impressionism/.