Mary Cassatt – The Life and Works of This Female Impressionism Artist

Mary Cassatt the artist was originally from America but relocated to France to train in the arts and would stay there for the rest of her life. It was in France that artists within the Impressionism movement began to take notice of Mary Cassatt’s paintings. Mary Cassatt’s self-portraits and portraits of others depicted young and old females engaged in everyday activities.

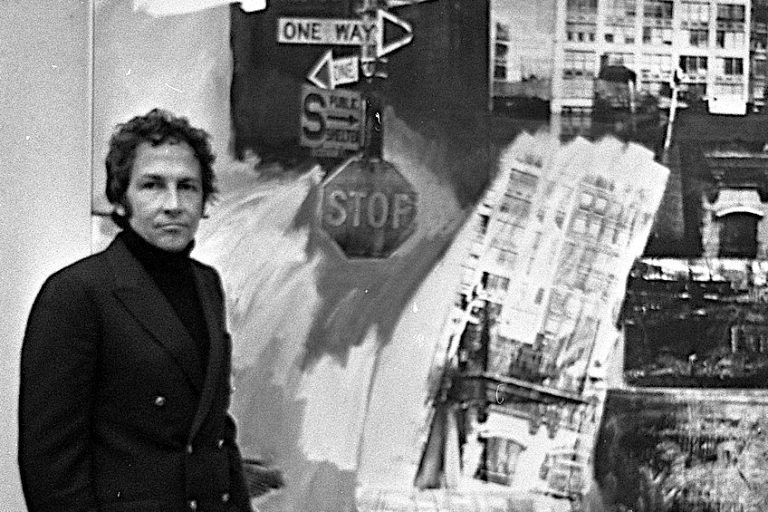

Mary Cassatt the Artist

Mary Cassatt’s prints and paintings demonstrated her technique as well as her incisive evocations of the lives and experiences of women from the late-19th-century era. Mary Cassatt’s paintings blended Impressionism’s light color palette and free brushwork with themes inspired by Japanese artwork as well as the Old Masters of Europe, and she produced in a number of mediums during her career.

Mary Cassatt the artist’s flexibility contributed to her professional reputation at a period when few females were considered as competent painters.

| Nationality | American |

| Date of Birth | 22 May 1844 |

| Date of Death | 14 June 1926 |

| Place of Birth | Allegheny City, Pennsylvania, United States |

Early Life and Training

From 1851 until 1855, Mary Cassatt lived in France and Germany with her family, providing the young child early exposure to European arts and culture. She also acquired German and French as a small girl, which would come in handy later in her international career. Little is known about her youth, however, she may have attended the 1855 Paris World’s Fair, when she would have seen the works of artists such as Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, Gustave Courbet, Eugène Delacroix, and Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, among others.

Cassatt commenced with her two years of education at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in 1860 when she was 16 years old. In 1865, she requested permission from her parents to pursue her artistic instruction overseas. Despite their reservations, they consented, and she relocated to Paris to study under Jean-Léon Gérôme. She returned to Paris after a brief trip to the United States from 1870 to 1871, when she was discouraged by a lack of creative resources and chances.

She also journeyed to Italy, Spain, and Holland in the early 1870s, where she became acquainted with the works of painters such as Peter Paul Rubens, Diego Velázquez, and Antonio da Correggio.

Mature Period

Cassatt had positioned herself in a Paris workshop by 1874. Her family joined her three years later. Her family was regularly used as models for her late 1870s and 1880s work, which featured numerous photographs of modern women at the theater and opera, as well as in gardens and parlors. Cassatt, who was always single-minded and self-sufficient, now had the chance to focus on her art in a place where, as she later stated, “Women did not have to strive for attention if they produced real work.”

Cassatt had a picture approved and lauded in the Salon of 1872, and she presented her art at subsequent Salons.

However, after the Salon rejected one of her submissions in 1875 and accepted none of her submissions in 1877, she grew disillusioned with the procedures and conventional preferences of Paris’s official art scene. She was overjoyed when the artist Edgar Degas asked her to join the group of independent painters known as the Impressionists in 1877. She was already a fan of Degas’s works, and she quickly became good friends with him; the two regularly collaborated, supporting and coaching one other. In this milieu, she also mingled with other artists. Camille Pissarro, for instance, was a senior participant of the group who served as Cassatt’s tutor. Berthe Morisot was another female Impressionist exhibitor; she was a near contemporary of Mary Cassatt, and she embraced Cassatt’s focus on household situations.

From 1879 until 1886, Cassatt exhibited alongside the Impressionists in Paris, and in 1886, she was featured in the debut significant exhibit of the Impressionism movement in America, held at the Durand-Ruel Galleries in New York.

She proceeded to concentrate on images of women in home interiors, with an Impressionist emphasis on hastily recorded moments of everyday life, and she moved away from oil painting and sketching and toward pastels and prints. Since it was shown at the 1878 Exposition Universelle, Japanese art had become immensely popular in Paris, and Cassatt (like many Impressionists) integrated its aesthetic methods into her own works.

Cassatt’s compassionate images of mothers and children had made her famous by the 1880s. These paintings, like many of her depictions of women, may have been successful for a specific reason: they met a cultural demand to idealize women’s household responsibilities at a time when many women were becoming interested in voting rights, clothing reform, better education, and social progress. Cassatt’s portraits of her fellow middle-class ladies, however, were never basic; hidden behind the light brushwork and new hues of her Impressionist style were layers of significance.

Cassatt herself never wed or had children, preferring to devote her adult existence to her work as an artist.

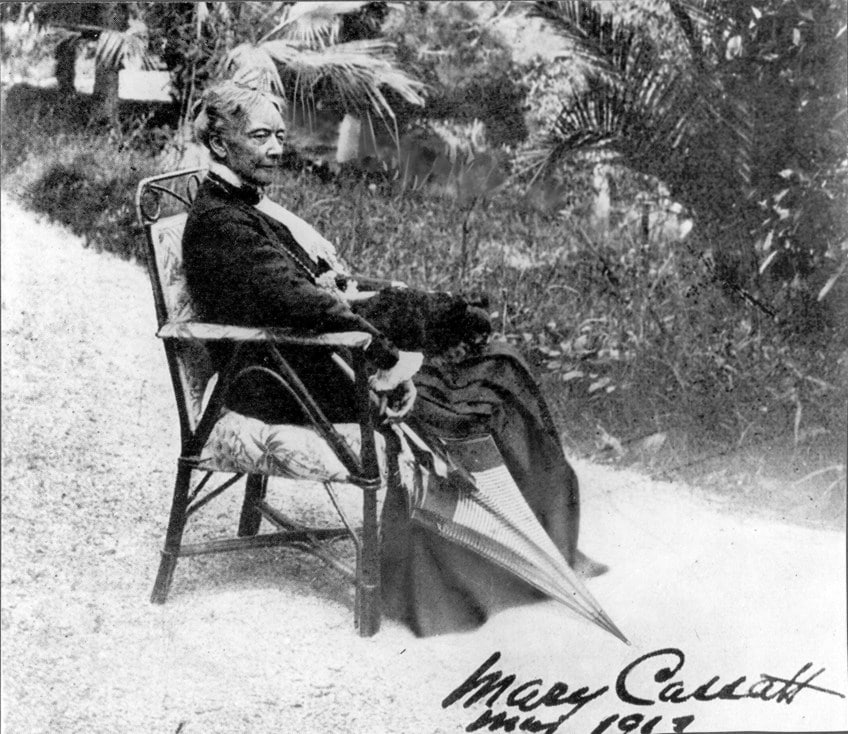

Late Life

Cassatt’s health deteriorated and his eyesight deteriorated after 1900. She did, however, retain strong relations with other artists and key individuals in the French art community, ranging from Pierre-Auguste Renoir to collectors Harry and Lousine Havemeyer.

Despite a schism in their connection during the historic Dreyfus incident of the late 1890s, in which Cassatt, like Monet and Pissarro, was pro-Dreyfus while Degas was anti-Dreyfus, the two eventually reconciled.

Cassatt was honored by the French government in 1904 for her cultural accomplishments. Cassatt was unable to work by 1914 owing to her deteriorating eyesight, although she continued to display her paintings. During World War I, she resided largely in Grasse until returning to her country house in Paris. Mary Cassatt passed away on the 14th of June, 1926.

Legacy

Cassatt worked throughout the 1910s, and by her late years, she had seen the rise of modernism in the United States and Europe, but her unique style remained consistent. After her passing in the 1920s, the decreasing critical interest in Impressionism meant that her effect on subsequent painters was limited. One exception was the “Beaver Hall Group,” a group of female painters headquartered in the 1920s in Montreal, Canada.

Cassatt’s place in art history, however, has been substantial and influential in the late 20th and early 21st centuries. Along with James McNeill Whistler, she is regarded as one of the most prominent American ex-pat painters of the late 1800s. She has also been the subject of major female artist studies, and her work has been analyzed by prominent feminist art historians such as Linda Nochlin.

Cassatt’s greatest visible impact might be her effect on American collectors who purchased her work and the art of her European colleagues and eventually gave it to museums.

Mary Cassatt’s Paintings

Mary Cassatt’s paintings frequently showed domestic settings, the environment to which she was bound as a respectable lady, rather than the more public locations that her male colleagues were permitted to occupy.

Her work was often derided as “feminine,” but most critics recognized that she brought substantial technical talent and psychological depth to her subject matter.

Cassatt became a prominent character in the art world and helped to develop the desire for Impressionist painting in her home United States by her commercial acumen and connections and professional contacts with painters, buyers, and patrons across the globe.

Little Girl in a Blue Armchair (1878)

| Date Completed | 1878 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 88 cm x 128 cm |

| Current Location | National Gallery of Art |

Cassatt opted to depict a little girl alone in a household atmosphere in this significant piece of her adult career. The obvious brushwork and casual stance of the person are trademarks of Impressionism; the asymmetrical arrangement, high viewpoint, small space, and abrupt cropping of the picture all reflect Japanese art’s influence.

Cassatt also incorporates her own insightful insights into the creation of this artwork. The girl, the child of a Degas friend, is situated in a sweeping, unselfconscious fashion that recalls her youth, and the way she is overshadowed by the adult’s furniture surrounding her conjures the discomfort and solitude of some periods of childhood.

In the Loge (1878)

| Date Completed | 1878 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 81 cm x 66 cm |

| Current Location | Museum of Fine Arts |

This artwork depicts a sophisticated woman watching a midday play at a famous Parisian theater. As she lifts a pair of opera glasses to her eyes, the woman’s profile contrasts with the crimson velvet and gold décor of the box seats behind her. The black of her gown is reflected in the attire of several persons in the background, along with a man several boxes down who is looking at her through his own spectacles.

Cassatt has picked up on the notion that the well-dressed members of the crowd are carrying on their own shows for each other.

The primary character may be observing the stage or studying her fellow theatergoers as she herself becomes the topic of the man’s attention; in the meantime, the spectator, who is positioned directly alongside the woman, takes in the entire action.

When this painting was shown in Boston in 1878, one writer applauded it, noting that Mary Cassatt’s paintings “surpassed the ability of most men.”

Lydia Reading the Morning Paper (No. 1) (Woman Reading) (1879)

| Date Completed | 1879 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 16 cm x 22 cm |

| Current Location | Joslyn Art Museum, Omaha, Nebraska |

Lydia Cassatt, the artist’s older sister, was among her favored sitters. Lydia is seated in profile in this picture, with her robe and face rendered in the very same free, airy brushwork as the backdrop and the chair that anchors her diagonally placed body inside the uneven composition.

The classic Impressionist color scheme of rose, white, light blues, and fresh green conjures up a lighthearted ambiance, but this is also a tense moment: By depicting her subject reading the paper, Cassatt makes reference to the value of women’s increasing reading skills in the 19th century, their rising participation in a societal structure outside the home, and their knowledge of the current occurrences as they started to struggle for voting rights.

Mary Cassatt Self-Portrait (1880)

| Date Completed | 1880 |

| Medium | Watercolor |

| Dimensions | 32 cm x 24 cm |

| Current Location | National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution |

This watercolor is one of just a few examples of Mary Cassatt’s self-portraits, which she painted about 1880, a year after she began showing her work among the French impressionists. Cassatt’s painting addresses the multiple responsibilities of the contemporary woman—as a mother, intellectual, and, in this case, professional artist.

Cassatt, despite her fashionable attire, is not satisfied to be admired and instead returns the viewer’s stare.

She playfully reverses assumptions by concealing her drawing surface, implying that the artist is applauding the spectator. Green strokes in the right backdrop indicate wallpaper, while a flood of brilliant yellow on the left depicts the sunlight that streams over the creator’s shoulders and puts her face into darkness.

Cassatt’s powerful strokes, emphasizing color, emotion, and motion, showcase her quick stroke and the modernity of her technique.

A Woman and a Girl Driving (1881)

| Date Completed | 1881 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 89 cm x 130 cm |

| Current Location | Philadelphia Museum of Art |

Cassatt captured the life of family interiors, theaters, and opera halls, as well as people in Paris’ gardens and parks, some of the few public locations where dignified ladies were able to roam freely in life. Lydia and Degas’ little niece served as models for this picture. The scene is the Bois de Boulogne, a huge, lush park that served as a popular gathering spot and picturesque location for leisure rides.

Cassatt focused on her subject, placing the horse on the left side of the arrangement and the vehicle on the right and bottom. The tiny child, clad in delicate pink, sits peacefully opposite the woman in charge; this contrast between youth and age, experiences and education, is one of Cassatt’s numerous psychological observations.

This piece was especially remarkable for its day in that it depicted a well-bred woman executing a physically demanding activity.

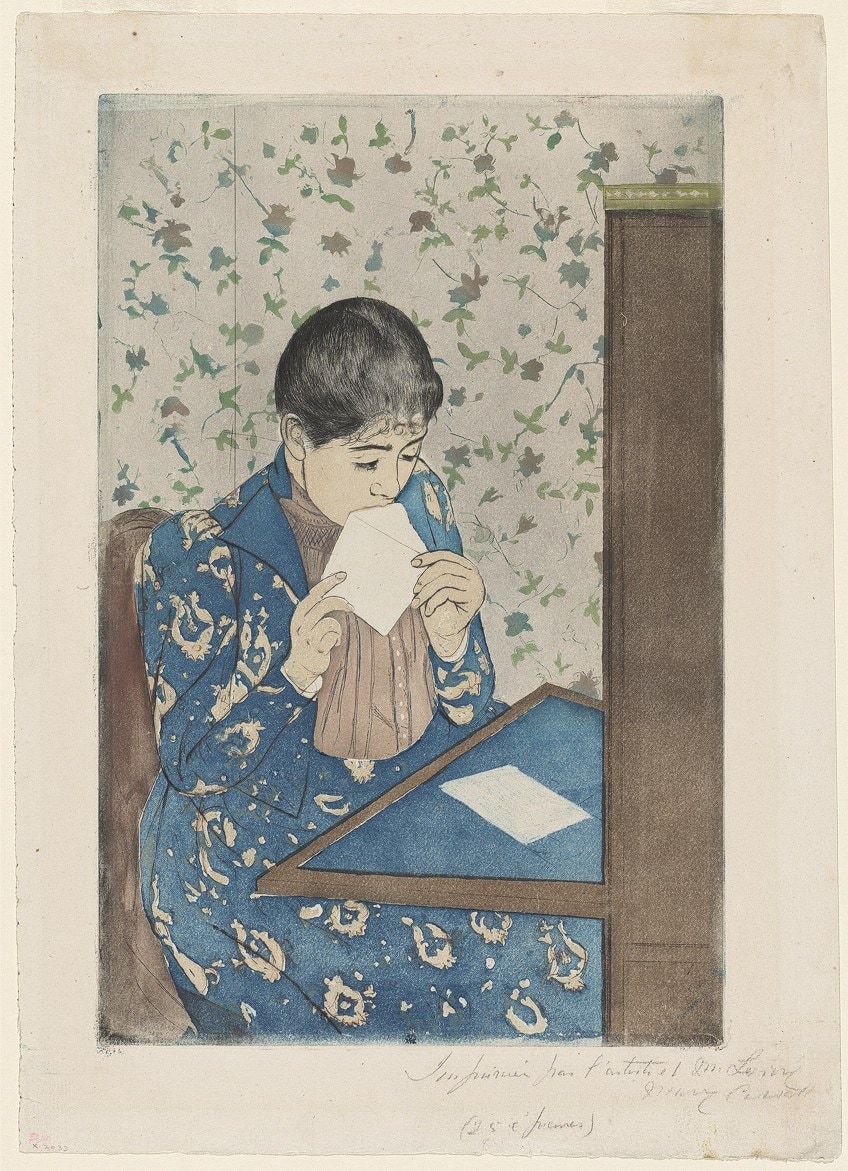

The Letter (c. 1891)

| Date Completed | c. 1891 |

| Medium | Drypoint and Aquatint on Paper |

| Dimensions | 34 cm x 22 cm |

| Current Location | The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York |

Cassatt saw an exhibit of Japanese colored woodcuts at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris in April 1890. As a result of this occurrence, she chose to produce a series of 10 prints depicting the life of a modern-day lady. The finished series of Mary Cassatt’s prints comprised scenes of ladies doing their toilettes, bathing their children, drinking tea, and so on; this instance depicts a lady sealing a letter she just wrote at her desk.

The composition contrasts patterns (the background, the woman’s outfit) with solid regions of color and draws the observer near to the room’s small space, where forced perspective is seen in the awkwardly slanted writing panel of the desk.

Although the woman’s clothing and other things are all modern features of Cassatt’s world, the artistic choices were influenced by traditional Japanese printing.

The Child’s Bath (1893)

| Date Completed | 1893 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 34 cm x 22 cm |

| Current Location | The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York |

In this child and mother painting, Cassatt mixes some artistic elements of Japanese painting with the subject matter of her own environment in this sensitively observed vignette of a lady washing her infant daughter. A restricted palette of grays and mauves unites the composition’s designs, which include many flower motifs and the vivid stripes of the woman’s dress; the gentle coloring lets the spectator focus on the scene’s theme, the tight bond between mother and baby.

The close positioning of their faces, as well as the circle of contacts that stretches from the mother’s hand on the baby’s foot, then concluding with the baby’s hand placed upon her mother’s knee, illustrate their connection. They are as intimately connected in their shared concentration on their job as the pitcher and bowl they are employing for this household rite.

Cassatt recalled the classic topic of the “Madonna and Child” in works such as this one, making her iconography secular rather than sacred.

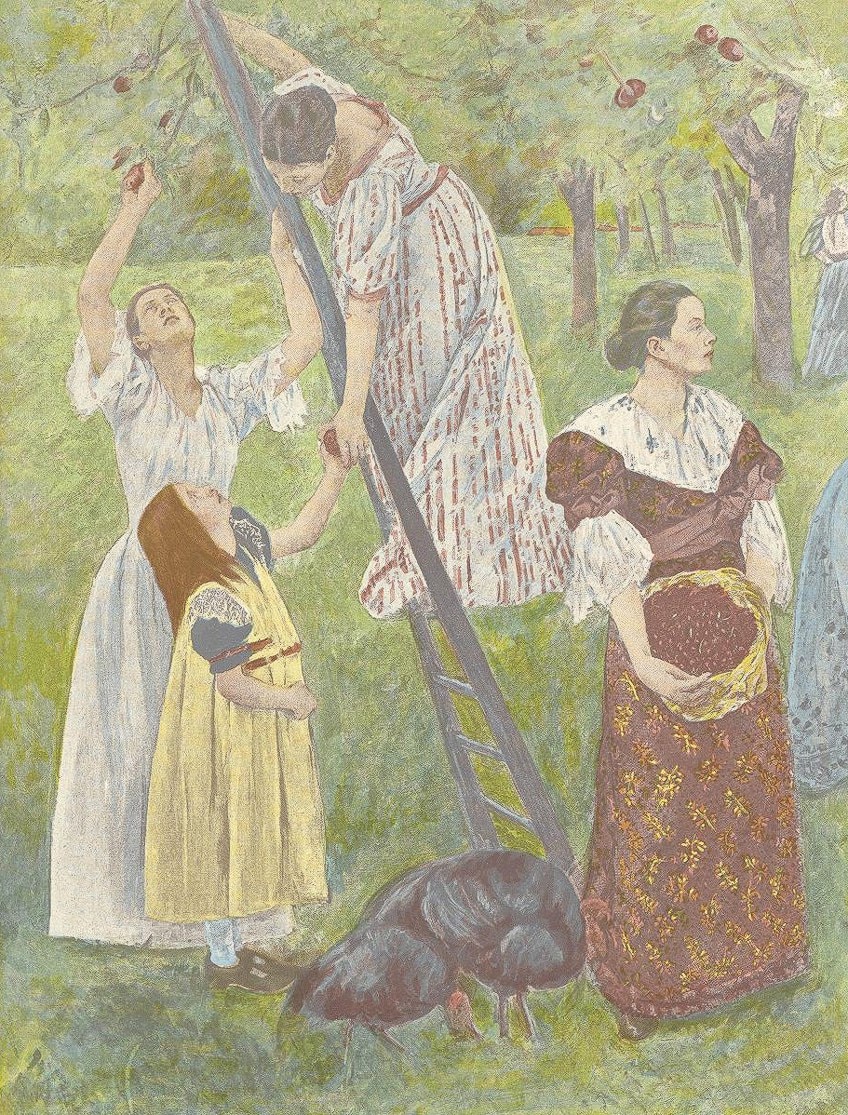

Art Institute of Chicago (1893)

| Date Completed | 1893 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 100 cm x 66 cm |

| Current Location | Destroyed |

This piece was made out of three panels. Regrettably, the whole painting was completely destroyed at the end of the exhibition, leaving just a few black-and-white images and a single-colored print of the middle panel to survive. This close-up of one of the panels reveals Cassatt’s sources and ideas for this colossal work.

The mural drew inspiration from influences as varied as Italian Renaissance murals, Japanese prints, and Les Nabis, but Cassatt combined these elements into something of hers.

She provided the viewers at the Columbian Exposition with a highly modern scenario that symbolizes female freedom and development on the eve of a new century in America by depicting a society of women aiding and encouraging one another.

Mother and Child (c. 1905)

| Date Completed | c. 1905 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 92 cm x 73 cm |

| Current Location | National Gallery of Art |

Cassatt was almost entirely dealing with the theme of mothers and children at the turn of the century, employing professional sitters for her images. In this child and mother painting, she again focuses her attention on an encounter between women at various phases of their lives. The mother’s elegant attire contrasts with the child’s pure nudity, and the two images are linked by their movements and gazes.

Cassatt created a complicated spatial and conceptual grouping of pictures inside images by integrating two mirrors in the composition.

From Diego Velázquez through to Édouard Manet, creatives have shown women staring in mirrors, considering themselves as items of attractiveness to be enjoyed by others. Cassatt was conscious of this Western art heritage, but she disregarded it in Mother and Child. The lady and daughter are both looking into the little, round mirror, where they are both looking at the child’s reflection.

The actual topics of this mysterious piece then become the little girl’s emerging feminine character and her eventual femininity under the tutelage of maternal guidance.

Recommended Reading

Would you like to learn even more about Mary Cassatt the artist? Known for her works within the Impressionism movement, she blazed a trail for the women who followed. Here are some books to learn even more about this amazing talent.

Mother & Child (2015) by Joe Gannon

This book celebrates the unique bond of infinite love and enduring devotion that exists solely between mothers and their children through uplifting words and the gorgeous imagery of Mary Cassatt. Cassatt’s fame stems from a sequence of paintings and prints she created later in her career showing the maternal connection. One of her paintings was even named Mother and Child.

- Inspiring poetry accompanied by the beautiful art of Mary Cassatt

- A celebration of the special relationship between a mother and child

- A selection of poems, each accompanied by a Mary Cassatt painting

Inside Out: The Prints of Mary Cassatt (2021) by Shalini Le Gall

This book analyzes the bold experimentation and creativity of one of the nineteenth century’s greatest and most innovative printmakers. As a printer, Mary Cassatt collaborated with Impressionists such as Camille Pissarro, and she achieved some of her best artistic successes. Her prints show the intimate and reflective side of an American painter who was at the core of the French art scene.

Mary Cassatt began her Impressionist career by painting largely figures of friends or family and their children. Cassatt’s versatility helped her build a professional reputation at a time when few women were regarded as capable painters. Mary Cassatt showed the 19th century’s “Modern Woman” from the viewpoint of a female.

Take a look at our Mary Cassatt paintings webstory here!

Frequently Asked Questions

Who Was Mary Cassatt?

Mary Cassatt the artist was a printer and painter from the United States. She was born in Allegheny City but spent much of her adult life in France, where she met Edgar Degas and exhibited among the Impressionists. Cassatt frequently depicted the private and social lives of females, with a focus on the close relationships between mother and child.

Why Were Mary Cassatt’s Paintings Important?

Mary Cassatt painted the so-called Modern Lady of the 19th century from the viewpoint of a woman. She began the significant beginnings in reconstructing the image of the new woman, influenced by her bright and energetic mother, who believed in teaching women to be informed and socially involved. Cassatt’s creative representation of women was always done with respect and the idea of a deeper, important inner existence, despite the fact that she did not openly make political pronouncements regarding women’s rights in her work.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Mary Cassatt – The Life and Works of This Female Impressionism Artist.” Art in Context. April 19, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/mary-cassatt/

Meyer, I. (2022, 19 April). Mary Cassatt – The Life and Works of This Female Impressionism Artist. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/mary-cassatt/

Meyer, Isabella. “Mary Cassatt – The Life and Works of This Female Impressionism Artist.” Art in Context, April 19, 2022. https://artincontext.org/mary-cassatt/.