Georges Seurat – A Look at Georges Seurat the Artist

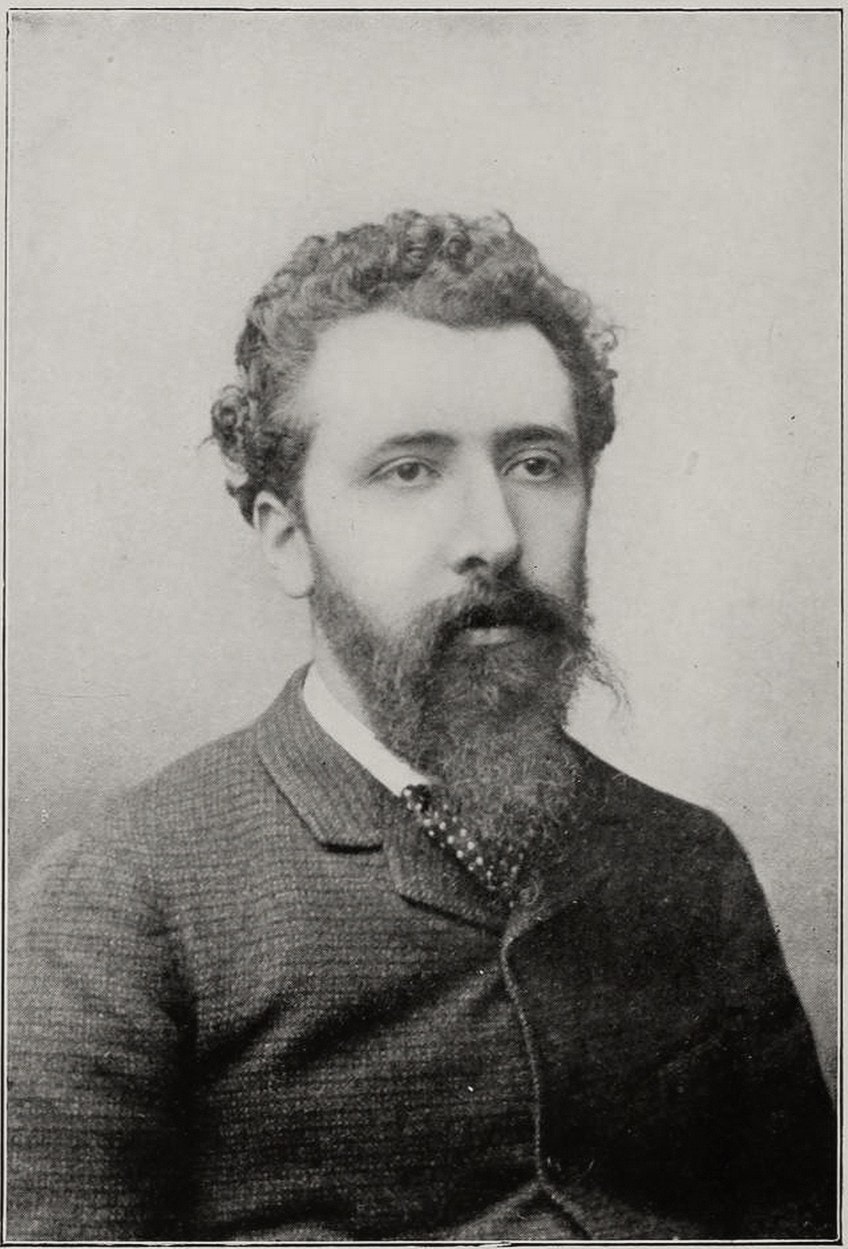

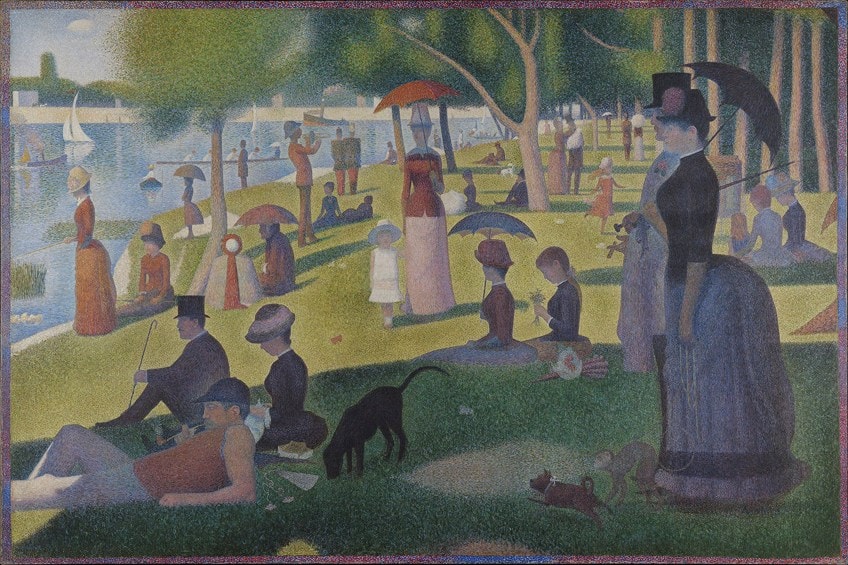

Georges Seurat was a French artist renowned as the creator of pointillism. Seurat’s Pointillism style can be observed in his famous Sunday in the park painting known as A Sunday on la Grande Jatte (1886). Georges Seurat’s paintings are regarded as the first examples of Neo-Impressionism, also known as Divisionism. Georges Seurat’s artworks are distinguished by a gently shimmering surface of little spots or streaks of color. Although Seurat the artist’s inventions sprang from new quasi-scientific ideas about colors and emotion, the exquisite elegance of his work may be explained by the impact of quite diverse sources.

A Georges Seurat Biography

| Nationality | French |

| Date of Birth | 2 December 1859 |

| Date of Death | 29 March 1891 |

| Place of Birth | Paris, France |

At first, Seurat the artist felt that outstanding contemporary art would depict present life in ways akin to traditional art, but using technologically advanced means. Later in life, he became increasingly intrigued by Gothic artwork and contemporary advertisements, and the effect of these on his works makes it some of the earliest contemporary art to employ such atypical forms of communication. His triumph catapulted him to the center of Paris’ avant-garde. His success was fleeting since he passed away at the age of 31 after only 10 years of mature production.

However, his advances would have a significant impact on the output of painters as varied as the Italian Futurists and Van Gogh.

Georges Seurat’s Early Life

Georges Seurat the artist was born on the 2nd of December in 1859, in Paris, as the last to be born of three siblings. Antoine Chrysostome, his father, was a magistrate; Ernestine, his mother, was from a wealthy family that had spawned numerous sculptors. By the time Georges Seurat was born, his unconventional father had practically settled with a little fortune, and he spent many days in Le Raincy, approximately 12 kilometers from the luxurious familial house in Paris.

The youthful Seurat shared a home with his mother and two of his siblings. The Seurat clan moved to Fontainebleau in 1870 for the duration of the Franco-Prussian War and the ensuing Paris Commune insurrection.

As a child, Seurat became interested in painting and was inspired by impromptu tuition from his uncle, Paul Haumonté, a fabric merchant and hobbyist artist.

Seurat the Artist’s Early Training

Seurat’s academic education started in 1875 when he enrolled at the nearby government art college under the tutelage of artist Justin Lequien. He met Edmond Aman-Jean while there, and the two of them enrolled in the École des Beaux-Arts. From early 1878 until late 1879, Seurat was a student at the Institute. The syllabus placed a strong focus on sketching and arrangement, and Seurat spent most of his hours creating from real models and casts made from plaster.

In his spare time, Seurat pursued his own creative interests and frequented libraries and museums across Paris. He also took guidance from artist Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, whose expertise was in large-scale traditional, mythological themes. Seurat’s drawings, which date from 1874, contain reproductions of Holbein’s works, a study of Nicolas Poussin’s hand from his celebrated self-portrait in the Louvre, and characters from Raphael’s illustrations.

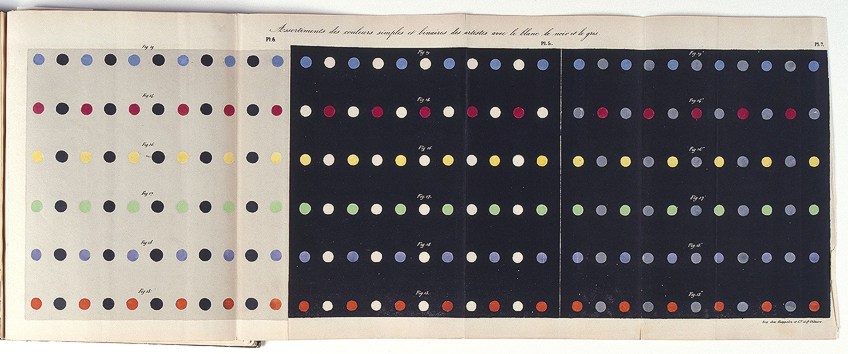

The Principles of Harmony and Contrast of Colors (1839) by Michel-Eugène Chevreul and The Grammar of Painting and Engraving (1867) by Charles Blanc exposed Seurat to various theories on color and the science behind optics, which were important to his reflection and activity as an artist. Chevreul’s revelation that by contrasting complementary hues, one might create the illusion of yet another color served as the foundation for Seurat the artist’s Divisionist approach.

Seurat went to the Fourth Impressionist Exhibition in April 1879. This was his first time seeing their works, and the oeuvre of Camille Pissarro and Claude Monet, painters free of academic restrictions, affected his subsequent experimentation considerably.

Seurat’s research culminated in a well-thought-out and productive theory of contrasts, to which all of his subsequent work was exposed.

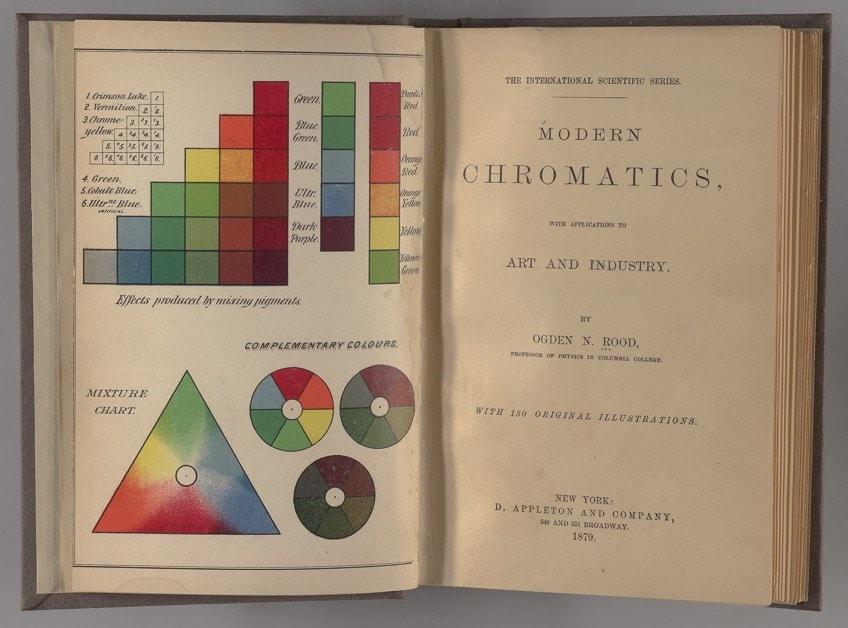

But his armed services duty began in November at Brest, where he spent all of his free time researching and sketching other cadets, coastlines, and city views. Seurat’s grasp of color theories and the impact of colors on the human eye grew over the years. He also researched the brushstrokes of Eugène Delacroix and read Modern Chromatics (1879) by Ogden N. Rood, which suggested that painters explore by the juxtaposition of small colored dots to observe how the eyes blend them.

Georges Seurat the Artist’s Career

The artist spent 1883 concentrating on his first big work, Bathers at Asnières (1884), a massive painting depicting youths resting by the Seine in a Parisian neighborhood. Despite being impacted by Impressionism in its utilization of hue and illumination, the work of art, with its seamless, streamlined textures and thoughtfully articulated, somewhat sculptural forms, demonstrates the ongoing impact of his neoclassical instruction; Seurat also deviated from the Impressionist standard by rehearsing the piece in his workshop with a series of sketches and oil drawings before beginning on the canvases.

The finished piece is a wonderful depiction of the light and ambiance of peak summer.

It is mostly painted in a crisscross brushwork style known as balayé, and he subsequently retouched it with spots of opposing color in select spots. Bathers at Asnières was not accepted by the Paris Salon, and he instead exhibited it in May 1884 at the Groupe des Artistes Indépendants. Yet, dissatisfied with the Indépendants’ lack of structure, Seurat and several other painters he met via the group – notably Henri-Edmond Cross, Charles Angrand, and Albert Dubois-Pillet – formed a new group, known as the Société des Artistes Indépendants.

Seurat the artist’s new views on pointillism had a particularly great impact on Signac, who later worked in the same manner.

Following the Bathers paintings, Seurat started work on A Sunday on la Grande Jatte (1886), a mural-sized painting that would take him two years to finish. Members of each socioeconomic class are seen in the picture indulging in various park activities. In preparation for the final piece, the painter traveled to La Grande Jatte, an island in the Seine situated in the Parisian district known as Neuilly, several times, doing sketches and more than 30 oil studies.

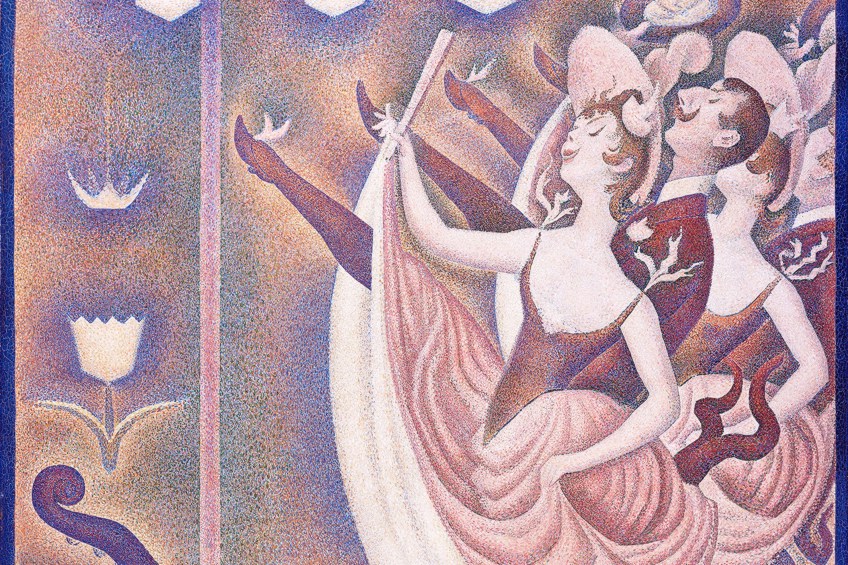

He recreated the picture in the winter of 1885 using a style he named “chromoluminarism,” sometimes referred to as Divisionism or Pointillism. The small juxtaposed specks of multi-colored paint enable the observer’s eye to visually merge colors instead of physically blending the colors on the canvas. When observed from a range, dots of opposing hue combine to produce a dazzling, rippling impression. Around 1887, he also repainted portions of the Bathers in the same manner.

In May 1886, Seurat displayed La Grande Jatte at the Eighth Impressionist Exhibition. Seurat distinguished himself as the head of a new avant-garde with his stunning visuals of color and light, as well as his sophisticated portrayal of diverse socioeconomic groups. The presentation of La Grande Jatte in 1886 unexpectedly sparked global attention in Seurat’s paintings.

Shortly after Seurat’s exhibitions, he was cited in an avant-garde journal, and several of his works were presented in both New York and Paris by the famous art merchant Paul Durant-Ruel.

Later Period

During this period, he became involved with a small community of Symbolist painters and authors headquartered in Paris. His new affiliations irritated his colleagues Pissarro and Signac, who thought he was abandoning fundamental color and lighting studies in favor of romanticized topics.

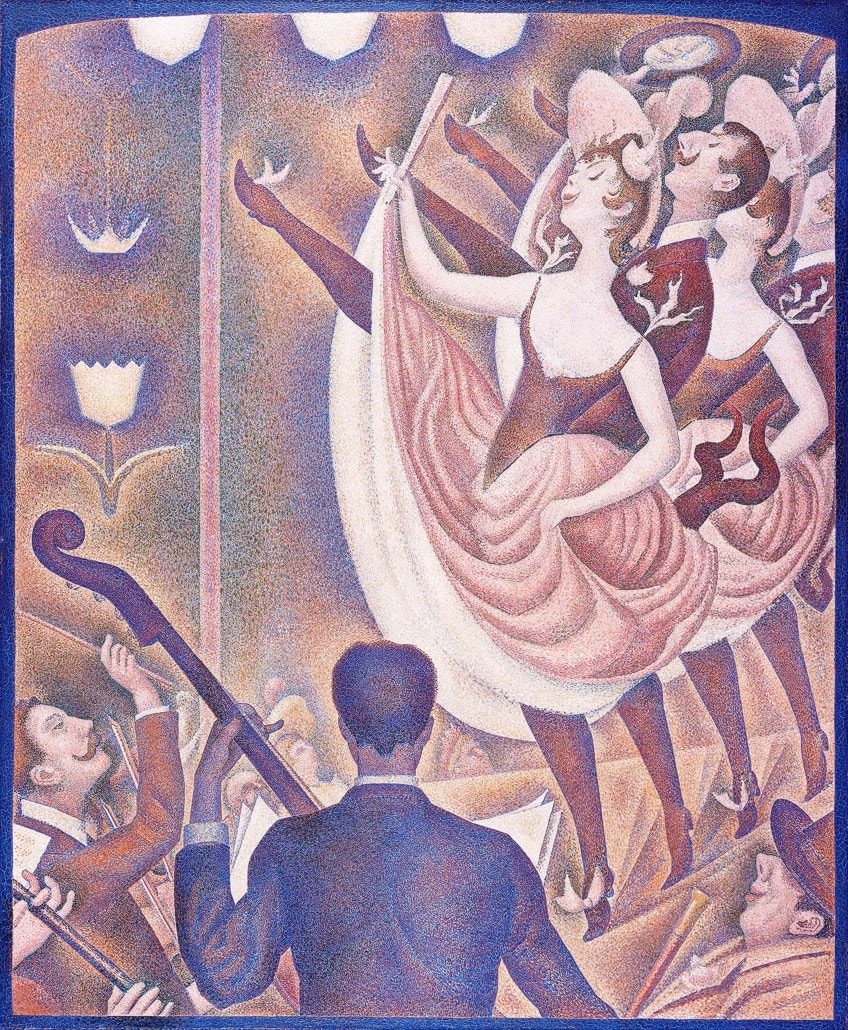

Seurat’s final important projects feature Paris nightlife and all have a similar subdued hue, which contrasts considerably with the exuberance of George Seurat’s paintings from an earlier era.

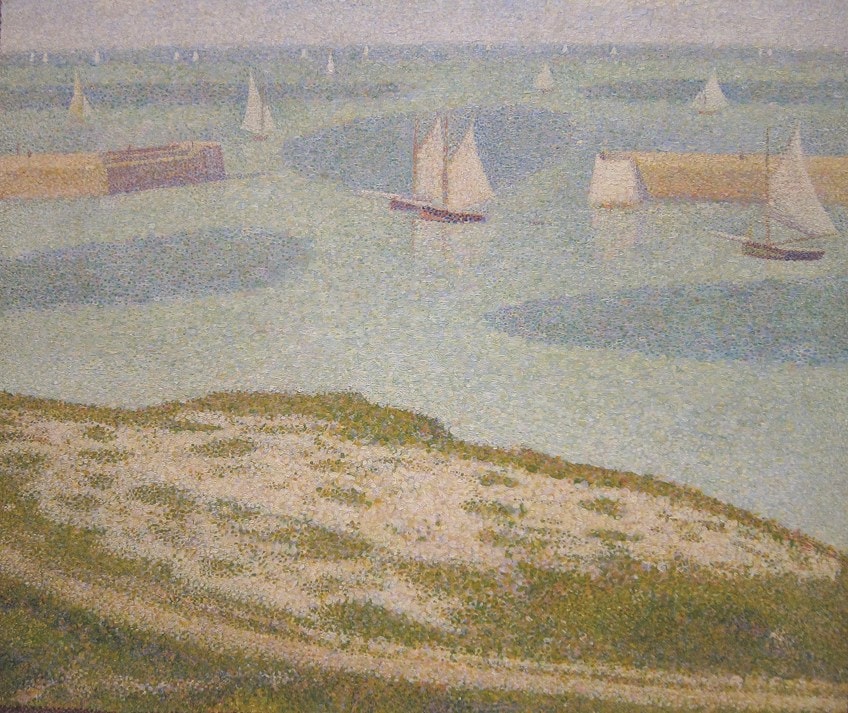

Seurat dedicated his summers on the Normandy coast, drawing seashore scenes of Port-en-Bessin in 1888 and Gravelines in 1890, with the exception of a short term of repeated military duty in the summer of 1887. In the wintertime, he completed these works and created enormous figure ensembles. Despite being produced in his Pointillist manner, the dots in his works were finer and more spread out, giving them a more natural aspect.

Seurat moved to Belgium in 1889 and was displayed in the Salon des Vingt in Brussels. After having returned from this journey, he met Madeleine Knobloch, a young beautiful model, and began living with her in secret. Unknown to his family and friends, Knobloch gave birth to a boy in February 1890. Seurat displayed his sole known picture of Madeleine, Young Woman Powdering Herself (1889-1890), in his Salon des Indépendants exhibition the following year.

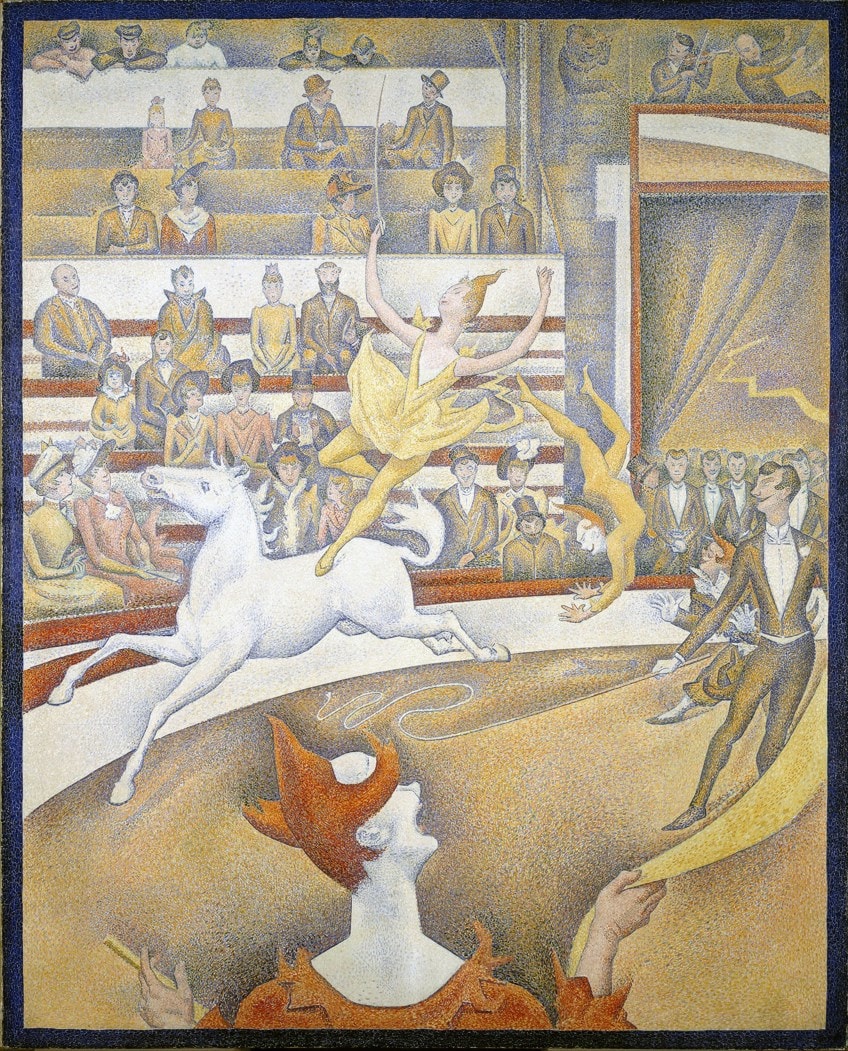

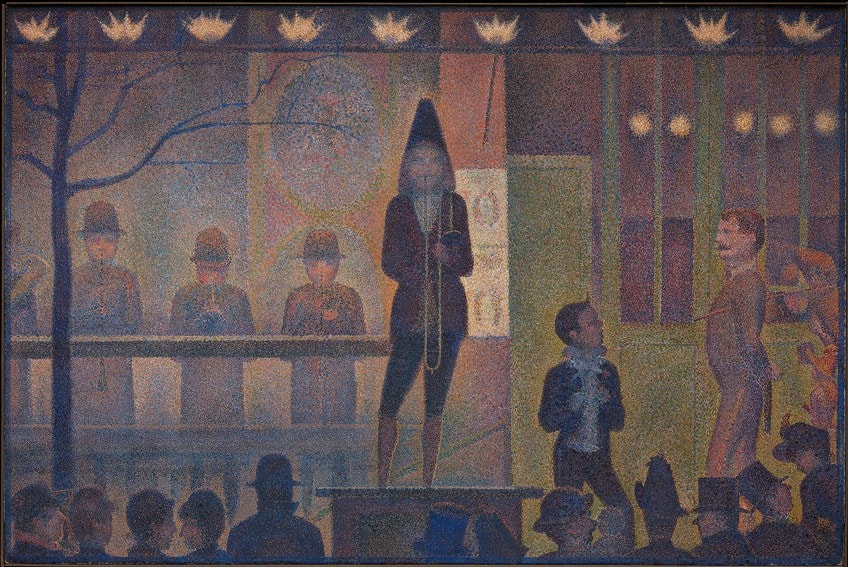

Madeleine Knobloch became pregnant again in early 1891 when Seurat was working on The Circus (1891). This artwork would not be completed. Seurat became unwell with a temperature on the 26th of March and perished three days later. In two weeks, his child died of a severe ailment and was placed beside Seurat in Paris’s Père-Lachaise cemetery.

Seurat’s Pointillism Art Style

Scientist-writers such as Ogden Rood, Michel Eugène Chevreul, and David Sutter authored treatises on color, optical phenomena, and perception during the 19th century. They converted Isaac Newton’s and Hermann von Helmholtz’s scientific studies into a manner that laypeople could understand.

Artists were enthralled by new breakthroughs in perception.

Modern Ideas

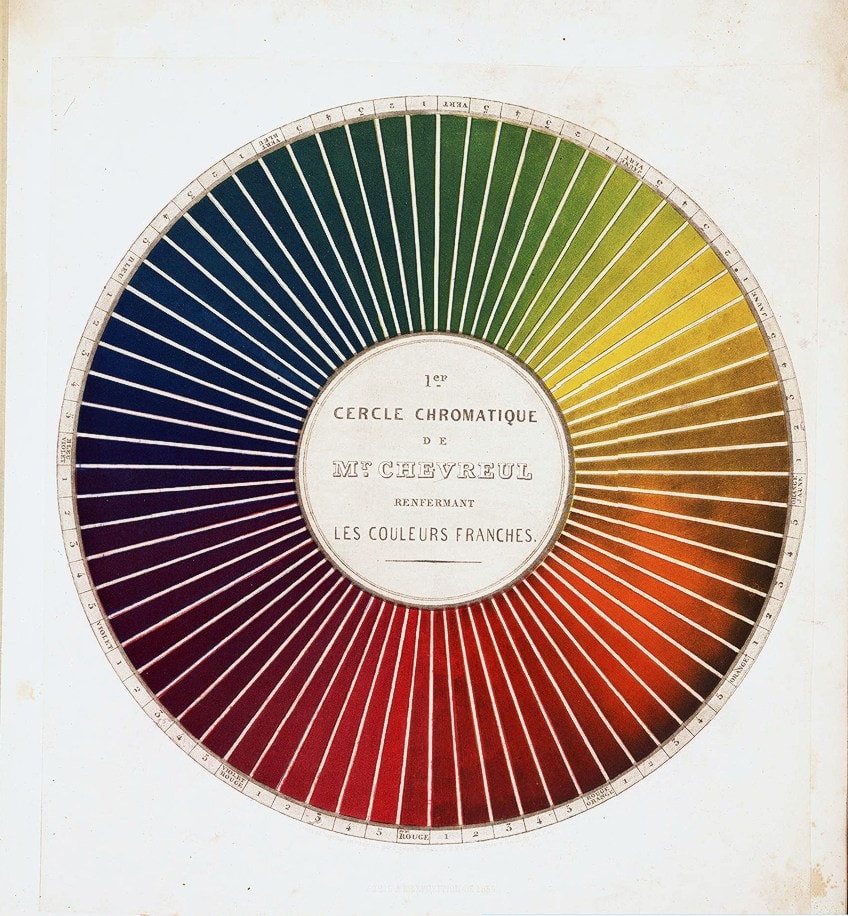

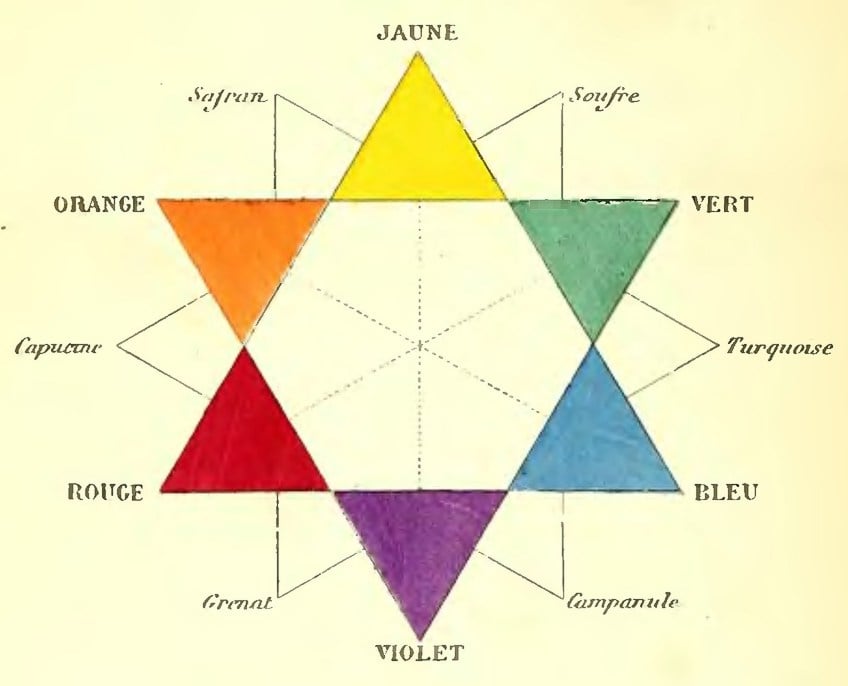

Chevreul was undoubtedly the most influential artist of the period, and his greatest contribution was the creation of a color wheel comprising primary and intermediate colors. He was a French scientist who specialized in the restoration of tapestries. During his repairs, he discovered that the only way to effectively repair a portion was to consider the effect of the colors around the lost wool; he couldn’t make the perfect hue until he knew the encircling dyes.

Chevreul observed that when two colors are juxtaposed, somewhat overlapping, or extremely near together, they appear to be another color when viewed from a distance.

The observation of this phenomenon served as the foundation for the Neo-Impressionist artists’ pointillist technique. Chevreul also discovered that the “halo” seen after staring at a color is the contrasting color. For instance, after viewing a red item, one may notice a cyan echo/halo of the original. The retinal retention causes this complementary color (for example, cyan for red).

Artists concerned with the interaction of colors, such as the Neo-Impressionists, made considerable use of complementary hues in their works. Chevreul instructed artists in his works to think about and create not simply the color of the focal item but to add colors and make suitable modifications to achieve color equilibrium. It appears that the harmony described by Chevreul is what Seurat came to term “emotion.”

It is unclear if Seurat studied the entirety of Chevreul’s book on color contrast, which was released in 1859, but he did write out many sentences from the section on paint, and he had examined Charles Blanc’s Grammaire des arts du dessin (1867), which acknowledges Chevreul’s work. Blanc’s book was written for artists and art collectors. Because of the emotional importance of color to him, he made clear suggestions that were similar to those later accepted by the Neo-Impressionists.

He stated that color should not be dependent on “assessment of preference,” but instead on what we feel in actuality. Blanc did not want painters to employ identical color intensities, but rather to plan and grasp the significance of each hue in producing a totality.

While Chevreul drew his conclusions on Newton’s ideas on light mixing, Ogden Rood based his articles on Helmholtz’s studies. He investigated the impact of combining and juxtaposing different material colors. Rood regarded green, red, and blue-violet as basic colors. He, like Chevreul, believes that if two colors are adjacent to one another, they appear to be a third separate color from a distance.

He also noted out that juxtaposing main colors adjacent to each other would produce a significantly more powerful and attractive color when experienced by the eye and brain than merely mixing paint.

Because material colors and optical pigments do not combine in the same manner, Rood instructed painters to be cognizant of the distinction between subtractive and additive characteristics of color. Sutter’s Phenomena of Vision (1880), in which he argued that “the rules of balance can be learned as one studies the principles of harmony and music,” also impacted Seurat. In the 1880s, he attended Sorbonne seminars by mathematician Charles Henry, who studied the emotional characteristics and symbolism significance of lines and color. The degree to which Henry’s concepts were embraced by Seurat is still debated.

The Color Language

Seurat embraced the color theorists’ concept of a scientific technique to painting. He felt that a painter might utilize color to produce harmony and emotions in art in the very same manner that a guitarist does with counterpoint and variety in music. He hypothesized that the scientific utilization of color was similar to any other natural rule, and he felt compelled to substantiate this hypothesis.

He believed that understanding vision and optical principles might be utilized to build a new vernacular of art founded on its own set of criteria, and he set out to demonstrate this vocabulary using lines, color strength, and color scheme. Chromoluminarism was the name given by Seurat to this language.

In an 1890 letter to the writer Maurice Beaubourg, he wrote: “Harmony is achieved via art. Harmony is the comparison of opposite and like components of tone, color, and line. Lighter versus darker in hue. The complementary colors are orange-blue, red-green, and yellow-violet. Those that make a straight angle in line. The framework is in a harmony that contrasts with the picture’s tones, colors, and lines; these features are analyzed in relation to their authority and under the effect of light, in merry, peaceful, or sorrowful combinations.” The following are some of Seurat’s theories:

- Joviality may be accomplished by the predominance of brilliant hues, the prevalence of warm colors, and the employment of upward inclined lines.

- Calm is accomplished by an equivalence of the usage of darkness and light, a combination of warm and cool colors, and horizontal lines.

- Sadness is conveyed by the use of dark and frigid colors, as well as downward-pointing lines.

The Influence and Legacy of Georges Seurat’s Artwork

Whereas Paul Cézanne’s work was immensely significant during the extremely expressive era of proto-Cubism from 1908 through 1910, Georges Seurat’s artwork, with its flat, more linear forms, would catch the Cubists’ interest beginning in 1911.

Seurat was capable of developing an esthetic philosophy with a new focused approach well matched to its presentation in his short years of activity, based on his findings on irradiation and the influences of contrast.

With the rise of monochrome Cubism in 1910–1911, issues of form supplanted color in the artists’ minds, and Seurat was increasingly important to these painters. His paintings and sketches were extensively viewed in Paris as a result of multiple exhibits, and replicas of his main pieces spread extensively among the Cubists.

Le Chahut (1890) was dubbed one of the excellent symbols of the new dedication, and it, along with the Circus (1891), is almost synonymous with Synthetic Cubism. The notion that art could be portrayed mathematically, in terms of both color and shape, was well understood among French painters.

This mathematical representation culminated in an autonomous and powerful “absolute fact,” possibly more so than the actual reality of the thing depicted.

Furthermore, the Neo-Impressionists were able to develop an objective scientific foundation in the field of color. Seurat takes on both issues in Le Chahut. Cubism would shortly follow in both the domains of form and motion and Orphism would do the same in color as well.

Georges Seurat the Artist’s Accomplishments

Seurat was propelled by a determination to renounce Impressionism’s fixation with the transient instance in favor of representing what he saw as the basic and unchangeable features of life. Nonetheless, he adapted many of his methods from the Impressionists, from his adoration of contemporary subject material and depictions of recreational time to his eagerness to avert displaying only the “native,” or obvious, the color of illustrated objects, but rather to encapsulate all the colors that communicated to generate their aesthetic.

A variety of scientific theories involving color, shape, and emotion captivated Seurat. He felt that lines pointing in certain directions, as well as colors of varying warmth or coolness, may have specific expressive effects. He also investigated the idea that opposing or complementary colors might optically blend to produce significantly more vibrant tones than paint alone. He dubbed his approach “chromo-luminism”, however, it is more often known as Divisionism.

Despite his innovative approaches, Seurat’s first instincts in terms of style were conventional and traditional.

A List of Georges Seurat Exhibitions

Georges Seurat’s paintings have been exhibited many times at the Salon. His work was also displayed at the Salon des Indépendants as well as the Eighth Impressionism Exhibit. Not only has his work been exhibited in France, but also in many countries abroad as well.

- 1883 – Salon, Paris

- 1885 – Salon des Indépendants, Paris

- 1886 – Impressionist exhibition, Paris

- 1887 – Les XX, Brussels

- 1889 – Salon des Indépendants, Paris

- 1891 – Les XX, Brussels

- 1931 – Gibbes Memorial Art Gallery

Georges Seurat’s Paintings That You Should Know

- Landscape at Saint-Ouen (1879)

- Overgrown Slope (1881)

- The Suburbs (1883)

- The Laborers (1883)

- A Sunday on La Grande Jatte (Study) (1885)

- Models (1888)

- The Eiffel Tower (1889)

- Young Woman Powdering Herself (1890)

- Circus (1891)

Recommended Reading

Georges Seurat’s biography reveals much about this famous artist. Georges Seurat’s artworks such as his famous Sunday in the park painting, titled A Sunday on la Grande Jatte, are famous for their unique pointillist approach. Yet, it is impossible to fit everything about the artist’s art and life into one article. If you would like to learn more about Georges Seurat’s paintings and life, then we suggest that you check out these awesome books on the subject.

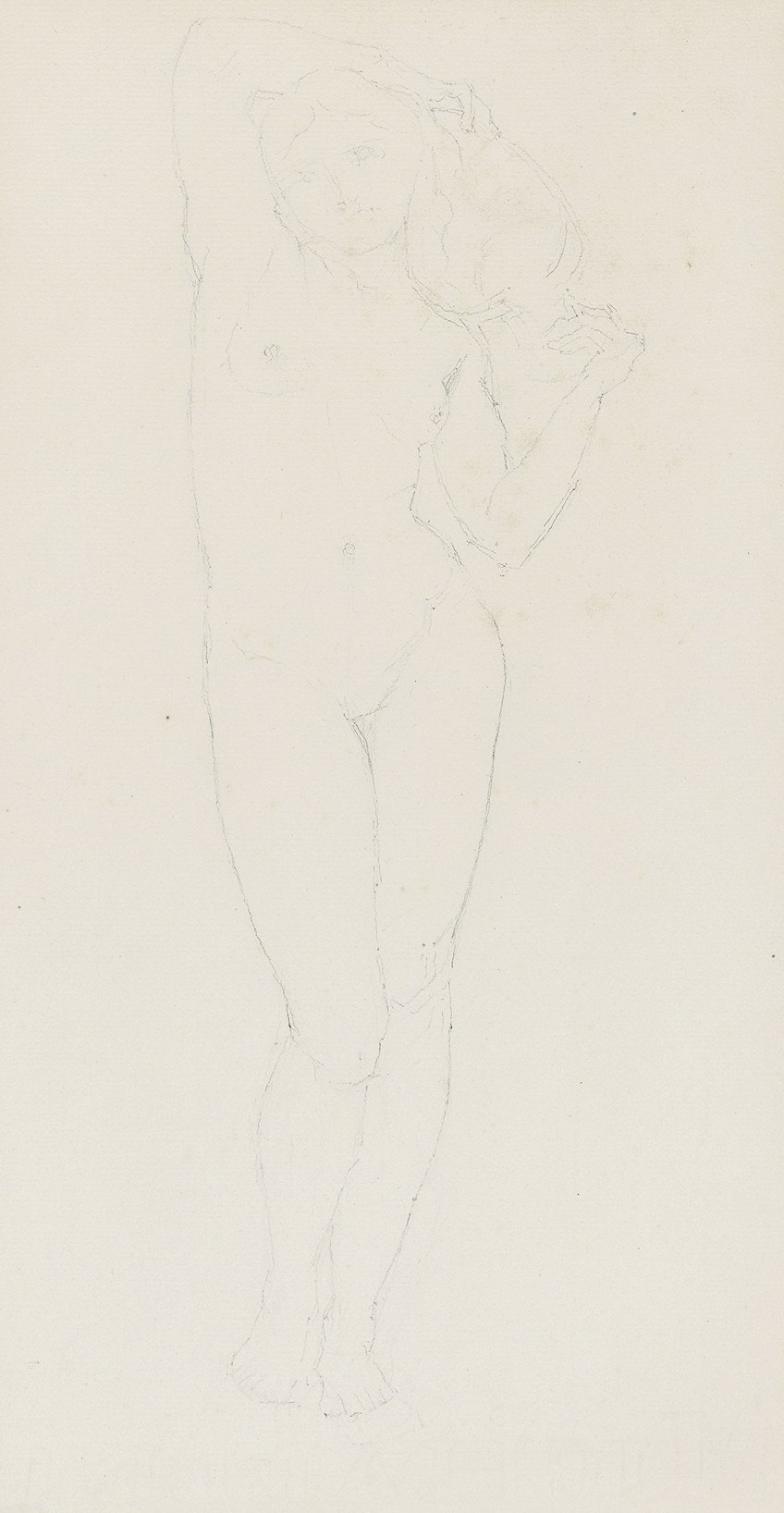

Georges Seurat: The Drawings (2007) by Jodi Hauptman

Georges Seurat’s cryptic and bright works on paper, sometimes characterized as “the most exquisite painter’s drawings in existence,” played an important part in his brief, energetic career. This comprehensive volume covers the artist’s whole work, from his academic background and the development of his distinct approaches through the preparatory studies for his colossal canvases. This collection, which accompanies the first exhibition in over 25 years to focus only on Seurat’s drawings, contains roughly 130 pieces, notably the artist’s outstanding conté drawings, as well as a limited selection of oil drawings and canvases.

Seurat used medium and paper to magnify radiating illumination and interact with the Parisian city, showing metropolitan types, industrialized suburbs, and 19th-century amusement in an effort to connect the seemingly opposing aims of observation and recollection. Though Seurat is best recognized as the creator of Pointillism, this collection illustrates his remarkable skill as a draftsman as well as his basic contribution to 20th-century art. It features carefully chosen details attentively as well as copies from pages of Seurat’s drawings that have never been released before.

- Seurat's mysterious drawings played a crucial role in his career

- A survey of the artist's entire oeuvre, including over 130 works

- A demonstration of Seurat's achievements as an artist and draftsman

Georges Seurat: Figure in Space (2010) by Christoph Becker

Georges Seurat was a pioneering artist who used paint to create fascinating effects, resulting in a “strange, almost breathless elegance.” His art demonstrates the airy floating of which “Pointillism” is particularly capable, a sensation perfectly adapted to expressing in paint the languid pace of Paris’ emerging leisure class. Pointillism was also a technique for Seurat to achieve the mathematically comprehensible balance of music in his paintings: “Harmony is achieved via art. Harmony is the similarity of opposite and similar components of tone, color, and line, as determined by predominance and under the effect of light, in joyous, tranquil, or sorrowful mixtures,” he stated in a letter to a friend.

Seurat’s approach fitted itself particularly well to the depiction of figures in space, as well as the imbuing of those forms with volume and mood. No other visual motif exemplifies the significant breakthroughs in Seurat’s paintings and sketches as effectively as this portrayal of the figure, which is central to this new judgment.

- Seurat revolutionized the art world with the Pointillism technique

- Looking at specific visual themes illustrated by Seurat's works

- Focuses on the figure in space in Seurat's paintings and drawings

Georges Seurat was a French artist well known for inventing pointillism. The Pointillism technique of Seurat may be seen in his classic Sunday in the park painting, “A Sunday on la Grande Jatte” (1886). The paintings of Georges Seurat are recognized as the first examples of Neo-Impressionism, often known as Divisionism. The artworks of Georges Seurat are defined by a softly shimmering surface of small patches or streaks of color. Although Seurat the artist’s discoveries arose from new quasi-scientific notions about colors and emotion, the exquisite refinement of his work may be explained by a variety of influences.

Frequently Asked Questions

Who Was Georges Seurat?

Initially, Seurat the artist believed that exceptional modern art would reflect contemporary life in ways similar to traditional art, but utilizing technologically sophisticated tools. Later in life, he grew increasingly fascinated with Gothic artwork and current commercials, and the impact of both on his works makes it some of the earliest contemporary art to utilize such unconventional modes of communication. His success propelled him to the forefront of Paris’ avant-garde. His popularity was brief, since he died at the age of 31 after only ten years of mature productivity. His innovations, however, would have a considerable effect on the work of artists ranging from the Italian Futurists to Van Gogh.

What Kind of Art did Georges Seurat Make?

Georges Seurat’s paintings are examples of pointillism or Neo-Impressionism. Seurat the artist was driven by a need to reject Impressionism’s fixation with the transient present time but instead just express what he saw as the core and permanent in life. Georges Seurat’s pointillism style is defined by a softly shimmering surface of small patches or streaks of color.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Georges Seurat – A Look at Georges Seurat the Artist.” Art in Context. December 21, 2021. URL: https://artincontext.org/georges-seurat/

Meyer, I. (2021, 21 December). Georges Seurat – A Look at Georges Seurat the Artist. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/georges-seurat/

Meyer, Isabella. “Georges Seurat – A Look at Georges Seurat the Artist.” Art in Context, December 21, 2021. https://artincontext.org/georges-seurat/.