James Abbott McNeill Whistler – Master of American Tonal Art

James Abbott McNeill Whistler was part of the late 19th-century creative revolution in London and Paris. Whistler’s paintings were created using a particular style derived from a variety of influences, and he reached a form of post-Impressionism in the mid-1860s, while many of his avant-garde peers were still experimenting with Impressionism and Realism. Whistler’s nocturnes, portraits, and etchings were all part of his renowned body of work.

James Abbott McNeill Whistler’s Biography

| Nationality | American |

| Date of Birth | 11 July 1834 |

| Date of Death | 17 July 1903 |

| Place of Birth | Lowell, Massachusetts |

Several early Parisian artists were excited by Japanese artwork. As he was among the first American artists working in England to incorporate magnificent oriental textile patterns and accessories in his paintings, Whistler is credited with developing the Anglo-Japanese approach in the fine arts.

Whistler was a firm supporter of the Aesthetic philosophy, espousing the concept of “artwork for the sake of art”.

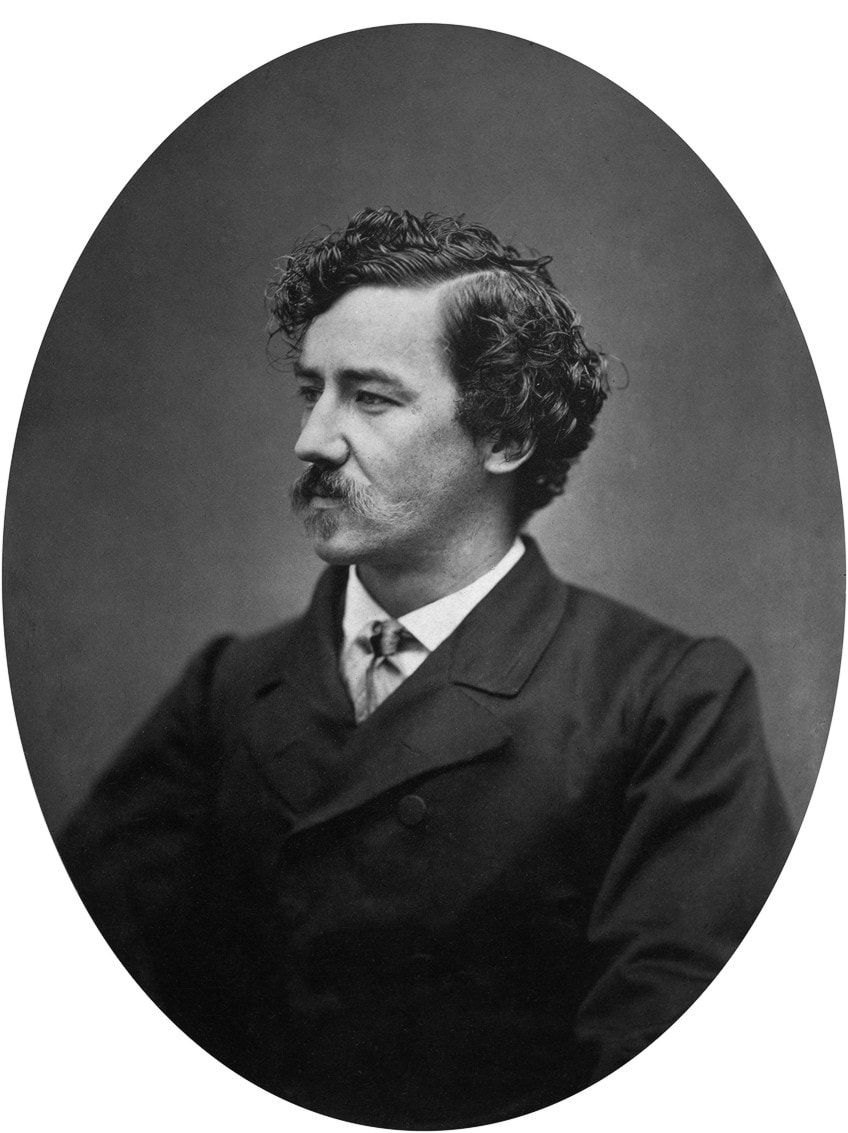

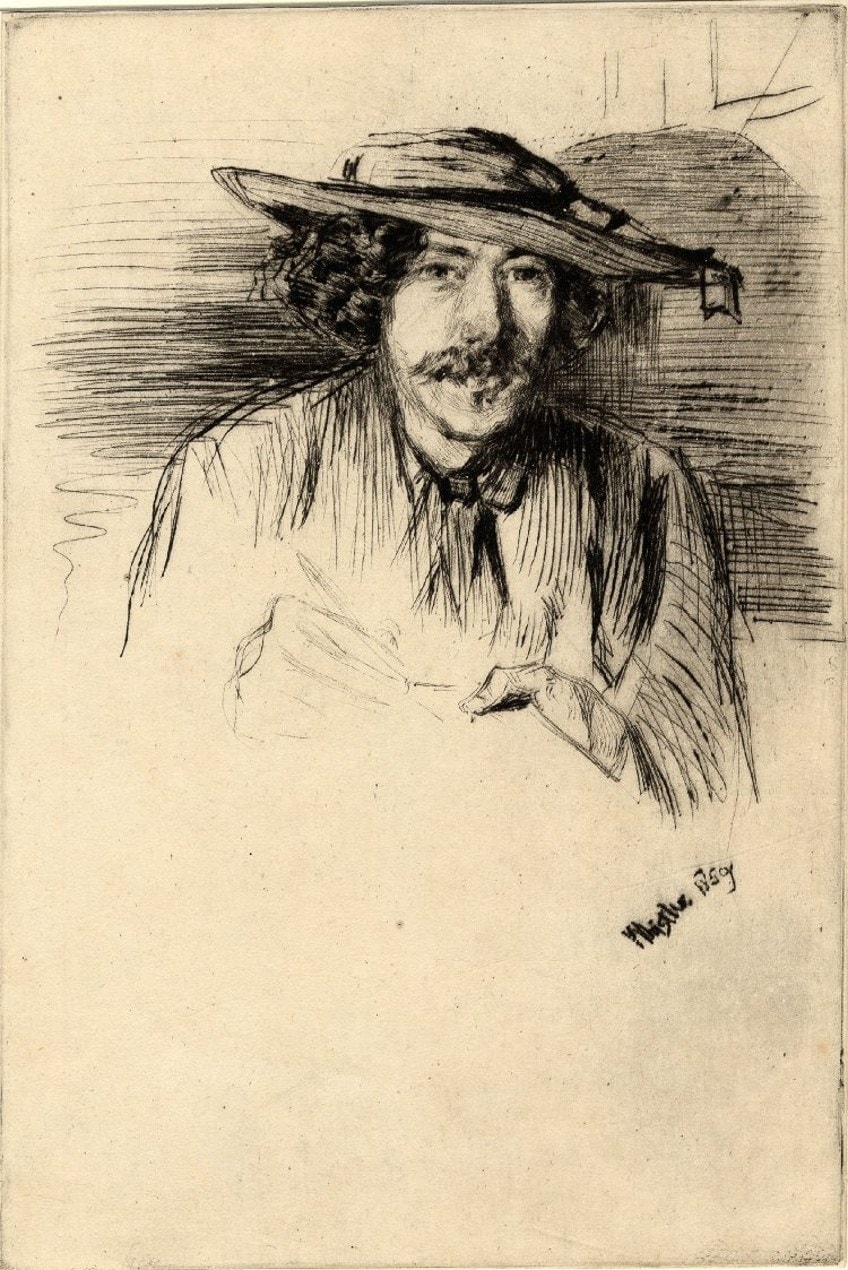

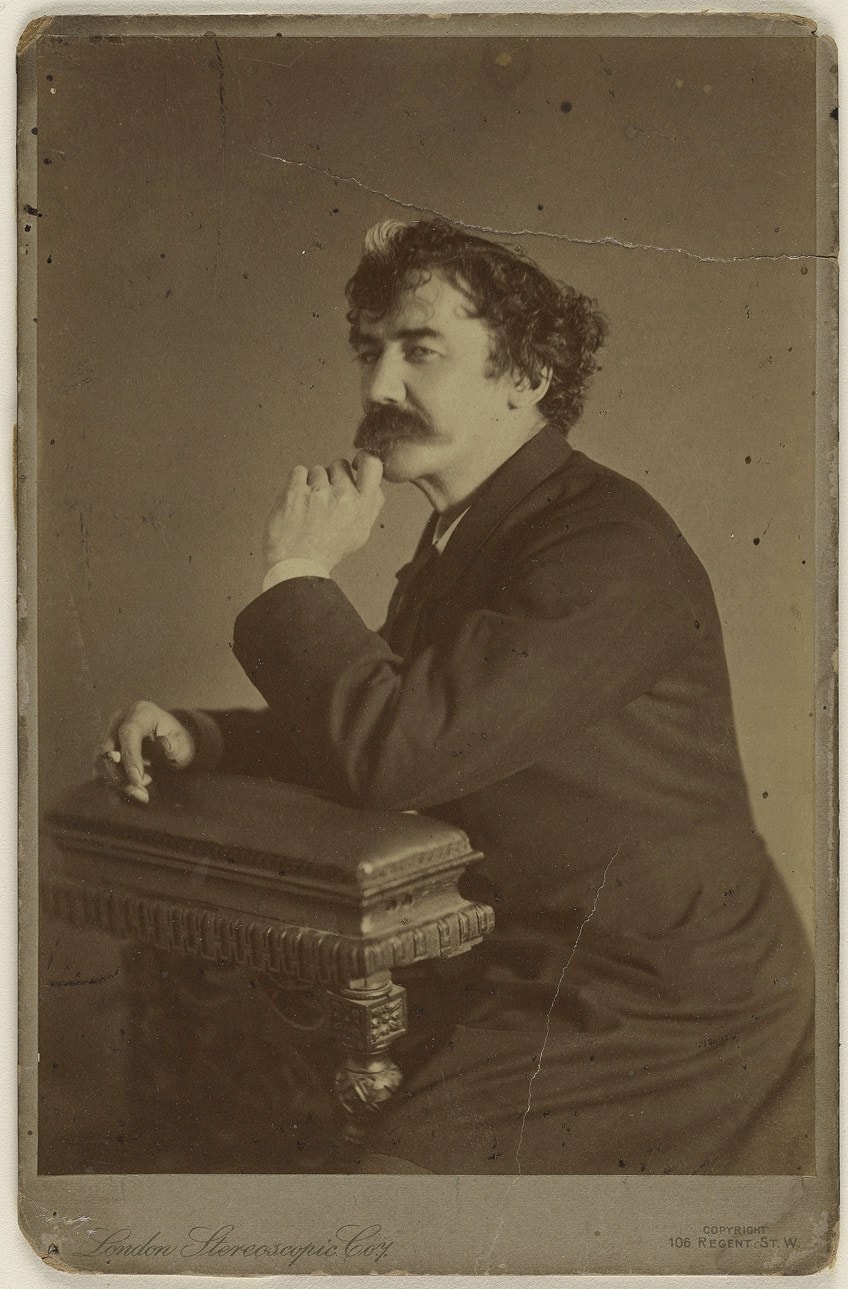

James McNeill Whistler, c. 1885; Unspecified. Joseph and Elizabeth Robins Pennell Collection (Library of Congress)., Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Childhood and Education

Whistler had a tumultuous childhood and was susceptible to mood changes. His parents immediately realized that drawing helped him relax, and they urged him to pursue his creative interests. When Tsar Nicholas I hired Whistler’s father to construct a railroad in 1842, James and his family relocated to St. Petersburg, Russia. Young Whistler’s sketches were given to Sir William Allan, the artist appointed by the Tsar to create a portrait of Peter the Great. Whistler was accepted into the Imperial Academy of Fine Arts at the age of 11 in 1845, thanks to Allan’s encouragement.

When his father died of cholera four years later, they relocated to America, residing in Pomfret, Connecticut. Notwithstanding their economic difficulties, Whistler’s mother worked very diligently to instill moral values in her offspring and to present them with every opportunity. She enrolled James in a Christian school and recited Bible Scriptures to him every day in the expectation that he would consider a career as a priest.

However, her son seemed unfazed in his quest for art.

Whistler joined the US Military Academy at West Point in 1852, where he studied drawing under Robert W. Weir but was discharged shortly after owing to his lack of control and poor educational performance. Whistler’s aptitude to create maps, which he acquired at West Point, enabled him to obtain his first employment after graduation as a topographic designer with the Geodetic Survey.

Throughout his two-month stay, the artist discovered the etching process, which he would later use to create 490 different pieces. In 1855, Whistler came to Europe, intent to earn a livelihood as an artist. He had no plans to go back to America.

Early Training

Whistler received an excellent education in Paris, where he briefly trained at the École Imperiale before joining the school of Charles Gabriel Gleyre, who later instructed Impressionists Camille Pissarro and Claude Monet. After being liberated from his mother’s religious influences, the 21-year-old quickly embraced the manner of a bohemian painter. He assumed the persona of a well-dressed flâneur, walking aimlessly along Parisian boulevards and taking in everything around him.

Friends referred to him as Jimmy, and he spent all his income on clothes, smokes, meals, booze, and art supplies.

To clear off his mounting debt, he was regularly obliged to sell his possessions or depend on the generosity of others. Whistler, an admirer of 17th-century Dutch and Spanish artists, copied and sold their works in the Louvre to help with his financial struggles. Whistler’s genuine artistic advancement started in 1858, when he met French artist Henri Fantin-Latour and painters Édouard Manet, Gustave Courbet, and Alphonse Legros, through him.

Whistler’s art method was highly altered by Courbet’s realism at this initial point in At the Piano (1858/1859), as seen by the earthy tones and finely textured areas. At the Piano, created the year the artist relocated to London, portrays a woman and her infant in the music room of their London house.

The artwork was well-received when it was displayed at the Royal Academy in 1860.

Whistler, on the other hand, rejected this Realist viewpoint within a few years in favor of a fantastical style that was more closely associated with Aestheticism in terms of decorative value. His use of oriental objects and devotion to Japanese aesthetic principles set him apart from the Realists, even more, driving him to higher levels within the Aesthetic movement.

Mature Period

In 1859, Whistler relocated to London permanently, but he continued to go to and exhibit his work in continental Europe, particularly France, but not always with the expected results. The Royal Academy of Arts in London and the Salon d’Automne in Paris, for instance, both rejected his picture of his lover Joanna Hiffernan. The discarded painting was displayed in the Salon des Refusés in 1863 with pieces by several avant-garde artists, notably Édouard Manet, under the name The White Girl.

Though it was mocked at the time by more conservative spectators, “The White Girl” is now regarded as an essential early instance of Contemporary art.

It is the first of numerous Whistler works that employed color to study structural and logical relationships in a visually pleasing manner, in accordance with the Aesthetic ideology of “artwork for the sake of art”. The artist’s brush strokes were as bold as his adventures. In 1866, Whistler sailed by mistake to Valparaiso, Chile. Some academics believe he was loyal to Chile’s army at the time and journeyed to help the Chilean military effort. Whistler created three seascapes that marked a shift in his artistic breadth, irrespective of why he went there.

These nighttime harbor landscapes, first labeled “moonlight” but subsequently modified to Whistler’s nocturnes, inspired Impressionist vistas of the Cremorne Gardens when the painter returned to London.

Whistler was exposed to Impressionism by fellow painters Camille Pissaro and Claude Monet, who had moved to London in 1870 to avoid the Franco-Prussian War. Around this period, Whistler created nocturnes by applying thin layers of paint with bright color specks to represent distant objects or boats.

Japanese aesthetic notions like as simplified forms and emotive lines, which may be seen in these pieces, were foreign to English Aesthetic artists.

Whistler’s nocturnes reflect his modernist focus on generating an impact at the cost of precise details and correct portrayal, comparable to his portraits and congruent with French Impressionist ideals. In truth, Whistler was requested to participate in the Impressionists’ first group display in 1874, but he declined.

Despite creating marine “nocturnes”, Whistler proceeded to create portraits for the next 10 years. His best-known work, Arrangement in Gray and Black (1871), also commonly known as Whistler’s Mother, was completed during this period and depicts his mother. The artwork was a big hit, but his carefree existence in London was cut short when his mother arrived in 1864.

When Whistler, 29, learned about her plans to live with him, he was forced to clear up his life, which included moving his lover Joanna Hiffernan out of his property and into an apartment.

Whistler’s status as a clever, outspoken man blossomed alongside his success as an artist. He once beat Oscar Wilde at dinner by calling out the writer’s habit of rewriting innovative terms. The painter, on the other hand, battled with mood changes and a quick temper, both of which he had fought with since childhood. Whistler’s romance with his mistress Joanna Hiffernan was torn apart by rage and jealously after she posed naked for his acquaintance Gustave Courbet.

Whistler’s strong persona harmed his work as a painter at times.

Whistler’s Harmony in Blue and Gold: The Peacock Room (1877), currently considered the greatest example of Anglo-Japanese artistic unification and the most significant addition to Aesthetic interior decoration, caused many conflicts between the painter and his backer Frederick Leyland. Whistler adored Japanese prints and porcelain. Whistler happily consented when Leyland asked him to make some minor changes to his dining room in order to exhibit his own porcelain collection.

The artist’s revisions, nevertheless, were more extensive than expected, culminating in a compensation dispute.

Whistler had conflicts with critics as well. To explain his approach to painting, he developed his own philosophy of art, which he described in 1873 as “the chemistry of color and ‘image pattern'”. Whistler sued John Ruskin for libel following what he perceived as an attack on his art in the form of a bad review.

Regardless of the fact that the painter succeeded, the judge’s award of a single farthing, or penny, conveyed a strong statement about the court’s attitude toward the case. Whistler nearly went bankrupt due to his incapacity to repay his exorbitant legal expenses.

Late Period

Whistler was well aware of his public image and worked hard to maintain it as a prominent painter. Friends attributed his “evilness” to him sporting a monocle and wandering with a bamboo walking stick, as well as having a single white forelock in his otherwise black hair.

He was noted for advising women on what to dress for his shows so that their attire would not conflict with the colors in his paintings.

In 1888, Whistler wedded Beatrix Godwin, a former student, and acquaintance. Because she was a reputable woman, her relationships assisted him in obtaining further commissions for job. The couple later moved to Paris, where Whistler established a workshop and had a period of prolific creativity before his wife passed away in 1896. Whistler later launched an art school, but his deteriorating health made the venture untenable. Whistler passed away in 1903, just two years after the facility closed in 1901.

James Abbott McNeill Whistler’s Paintings

Whistler’s paintings typify the modern urge to produce “artwork for the sake of art”, an attitude that Whistler and others in the Aesthetic movement embraced. They also mark one of the earliest shifts from traditional realistic paintings to abstractions, which is important to contemporary art. Now it is time to take a look at some influential and famous examples of Whistler’s paintings.

Symphony in White No. 1 (1862)

| Date Completed | 1862 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 213 cm x 107 cm |

| Current Location | The National Gallery of Art, Washington DC |

Joanna Hiffernan, Whistler’s lover and model, is depicted in this picture with long, cascading red hair and a plain white cambric outfit. Her distant expression gives her a doll-like impression as she is located on a bear rug with a matching color palette and a white blossom at her sides. Furthermore, Whistler treats her as a tool or toy, preferring to utilize the painting to experiment with tone shifts rather than the reality of portraiture.

The fact that Whistler eventually renamed the painting “The White Girl” to emphasize the work’s shifting white tones and to suggest a connection to music notes emphasizes this goal.

Harmony in Blue and Silver: Trouville (1865)

| Date Completed | 1865 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 51 cm x 56 cm |

| Current Location | Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston |

A lone figure walks on a beach in this picture, one of at least five painted by Whistler at Trouville, staring out across the vast expanse of the sea before him. The figure’s gaze draws our attention to two sailboats out to the right of the high horizon line. Gustave Courbet, a Realist painter who accompanied Whistler to Trouville in 1865 when this work was painted, is the bearded man portrayed on the coast.

Whistler modified the title from “Courbet – on Sea Shore” to show his developing interest in linking his paintings with musical pieces.

The individual and the setting in which he lives practically vanish within Whistler’s delicate washes of color produced with sweeping brushstrokes of thinned paint. The picture pays homage to Courbet, who had a significant effect on Whistler’s early creative growth, while also signaling Whistler’s shift away from realism or towards Aestheticism. Trouville has no obvious moral message or purpose.

This painting demonstrates Whistler’s experimenting with color tones and methods of applying paint on the canvas to improve the visual or sensual stimulus.

Nocturne: Blue and Gold – Old Battersea Bridge (1872)

| Date Completed | 1872 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 68 cm x 51 cm |

| Current Location | Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom |

The picture depicts a nighttime view of the Thames River in London. The front of the picture features a pier of Battersea Bridge, with Chelsea Old Church’s tower and the freshly erected Albert Bridge viewable in the background. Fireworks emerge like specks of color in the sky beyond the bridge. Whistler sketched while traveling in a boat down the river in the early hours of the evenings to produce these paintings.

To produce these thinly painted, ethereal vistas of peaceful serenity, he relied on his memories and those basic sketches.

The painting’s compositional parallels to works by Katsushika Hokusai, one of Whistler’s beloved Ukiyo-e artists, demonstrate the artist’s affinity for the Japanese aesthetic. This piece is regarded as the “most Japanese” of Whistler’s nocturnes. In Whistler’s libel trial against John Ruskin, Old Battersea Bridge was used as proof of the artist’s skillful representation of an artistic image or recollection of a fleeting moment.

As a result, Whistler contended, the topic becomes secondary, and the connection between color and form takes precedence.

Recommended Reading

Today we covered James Abbott McNeill Whistler’s biography and art. There is always so much more to learn and discover though. Here are some handy book choices to help you out.

James McNeill Whistler: Tonalism (2011) by Daniel Ankele

Reproductions of portraiture, vistas, and nocturnes with title, date, and relevant data page are included in the James McNeill Whistler Art Book. Reference list, thumbnail galleries, and reformatted for all Kindle devices and Tablets are included in the book. A wonderful addition to any art enthusiast’s collection.

- Contains 165+ reproductions of portraits, landscapes, and nocturnes

- Each artwork is accompanied by a title, date, and interesting facts

- Also formatted for use with Kindles and tablets

Delphi Paintings of James McNeill Whistler (2017) by James McNeill Whistler

Whistler, an American painter who was opposed to sentimentality and moral implication in his work, became a major proponent of the philosophy of “artwork for art’s sake”. Whistler saw a similarity between painting and music; thus, he gave musical names to many of his works, emphasizing the importance of tonal harmony. His inventive and modern approach to painting, despite often disastrous results, has earned him a significant position in the history of modern art.

- Presents Whistler’s complete paintings in beautiful detail

- With concise introductions and hundreds of high-quality images

- Fully indexed paintings, including reproductions of rare works

Since he was one of the first American painters working in England to incorporate magnificent oriental textile designs and accessories in his paintings, Whistler is credited with pioneering the Anglo-Japanese approach in fine art. Whistler was a strong believer in the Aesthetic philosophy, advocating “artwork for the sake of art”. McNeill, James Abbott Whistler was a key figure in London and Paris’ late-nineteenth-century creative revolutions.

Frequently Asked Questions

Who Was the Artist James McNeill Abbott Whistler?

Whistler’s paintings were developed in a distinct manner and influenced by a wide range of inspirations. He achieved a sort of post-Impressionism in the mid-1860s, while many of his avant-garde contemporaries were still experimenting with Impressionism and Realism. Nocturnes, portraits, and etchings were all part of Whistler’s acclaimed body of work.

What Style Were Whistler’s Paintings?

By limiting his color palette and tonal contrasts while distorting perspective and highlighting the painting’s flat, abstract aspect, Whistler exhibited a new compositional style. Whistler labeled his works using phrases that suggested a link between musical notes and color tone changes. These more abstract titles are intended to draw the audience’s eye to the designer’s use of paint instead of the subject matter being shown.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “James Abbott McNeill Whistler – Master of American Tonal Art.” Art in Context. June 1, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/james-abbott-mcneill-whistler/

Meyer, I. (2022, 1 June). James Abbott McNeill Whistler – Master of American Tonal Art. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/james-abbott-mcneill-whistler/

Meyer, Isabella. “James Abbott McNeill Whistler – Master of American Tonal Art.” Art in Context, June 1, 2022. https://artincontext.org/james-abbott-mcneill-whistler/.