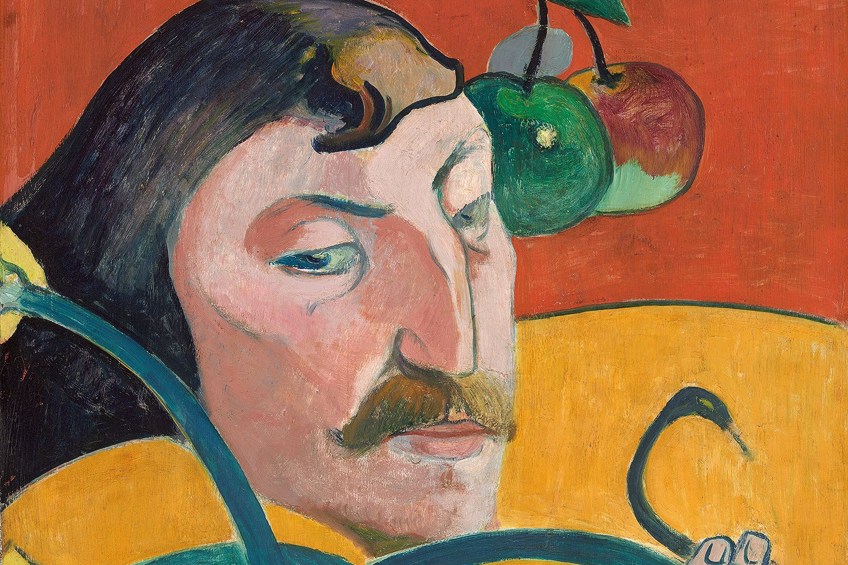

Paul Gauguin – Influential Primitivist Post-Impressionist

Who is Paul Gauguin? What was he famous for and how did Paul Gauguin die? These are all questions we intend to answer regarding this revered French painter. Although not recognized during his lifetime, Gauguin the artist is today regarded as a highly influential character of the post-Impressionist movement.

An Introduction to Paul Gauguin’s Biography

Paul Gauguin is also regarded as a key figure of the Symbolist movement. The famous French painter’s style explored the intrinsic essence of the subject matter of his artworks and cleared the path for subsequent movements such as Primitivism. By exploring Paul Gauguin’s biography, we can gain a deeper insight into what drove him as an artist. From his early days to Gauguin’s Tahiti experience – each chapter offers us a glimpse into the life of an artistic master.

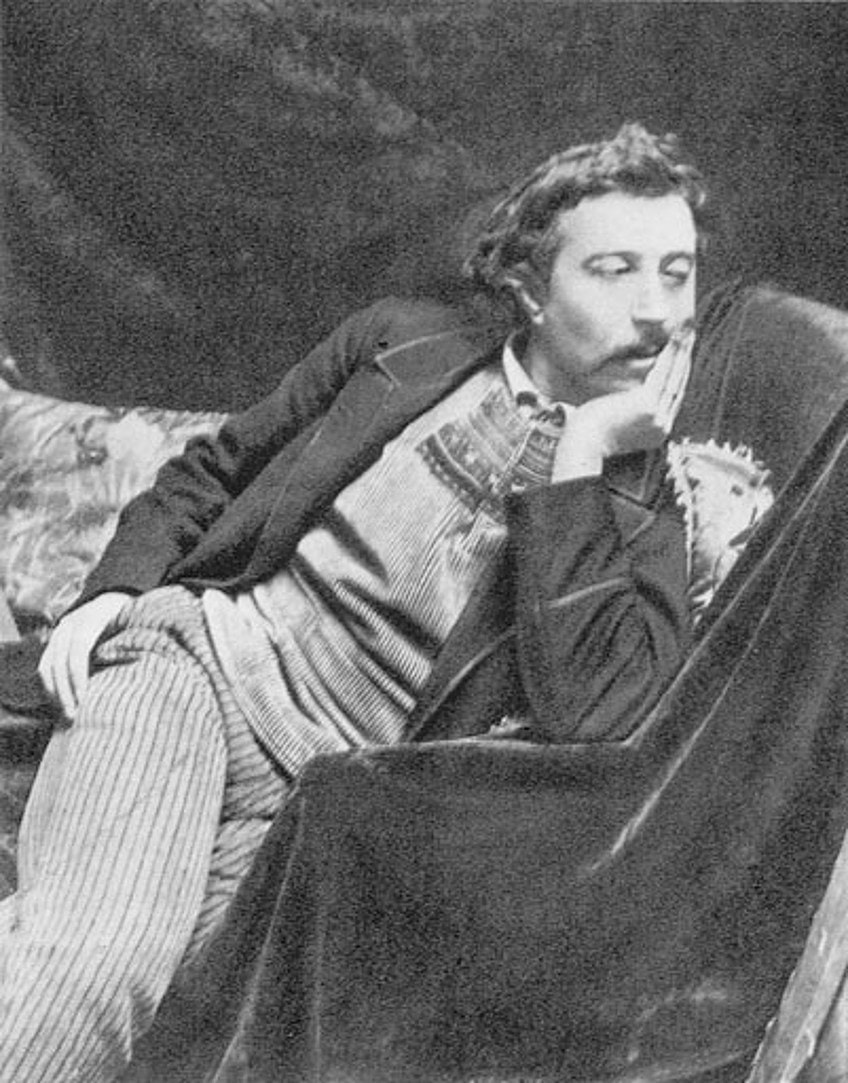

Paul Gauguin the Artist’s Early Years

Paul Gauguin was born on the 7th of June, 1848, in Paris. His birth overlapped with the year’s tumultuous events across Europe. The Gauguin’s left for Peru in 1850, as his father hoped to continue his investigative profession through his wife’s South American connections. He succumbed to heart failure along the way, and Aline landed in Peru as a widow with her children. Paul had a luxurious life until the age of six, with nannies and attendants seeing to him.

He had strong memories of that time in his boyhood, which left unforgettable recollections of Peru that tormented him for the rest of his life.

Gauguin was sent to a prominent Christian boarding house after studying at a handful of local institutions. He enrolled in a military training academy at the age of 14 before heading to Orléans for his last year. Gauguin joined the commercial navy as a pilot’s aide. He entered the French navy three years later and was deployed for two years. Gauguin traveled back to Paris in 1871, where he found work as a broker.

French Painter Paul Gauguin’s First Artworks

Gauguin began painting in his spare time in 1873, at the same time he became a stockbroker. The Impressionists visited the cafés nearby his residence. Gauguin also frequented galleries and acquired works by new painters. He befriended Camille Pissarro and paid him visits on Sundays to create in his yard. Pissarro connected him with a number of other painters. Close by lived his good friend Émile Schuffenecker, a retired stockbroker who desired to be a painter as well.

In 1882, Gauguin exhibited works in Impressionist exhibits.

At first, his works went unnoticed, but many of them, including the Market Gardens of Vaugirard (1879), and Winter Landscape (1879), are now widely valued. The stock market plummeted in 1882, and the art industry shrunk. The crisis had a particularly negative impact on the Impressionists’ major art distributor, who for a while ceased buying paintings by artists such as Gauguin.

Gauguin’s income fell precipitously, and over the next couple of years, he gradually developed ambitions of becoming a full-time painter. He produced with Pissarro and, occasionally, Paul Cézanne for the next two summers. Gauguin had written to Pissarro in October of 1883, indicating that he had determined to make a livelihood from art at whatever cost and asking for his assistance, which Pissarro first easily supplied.

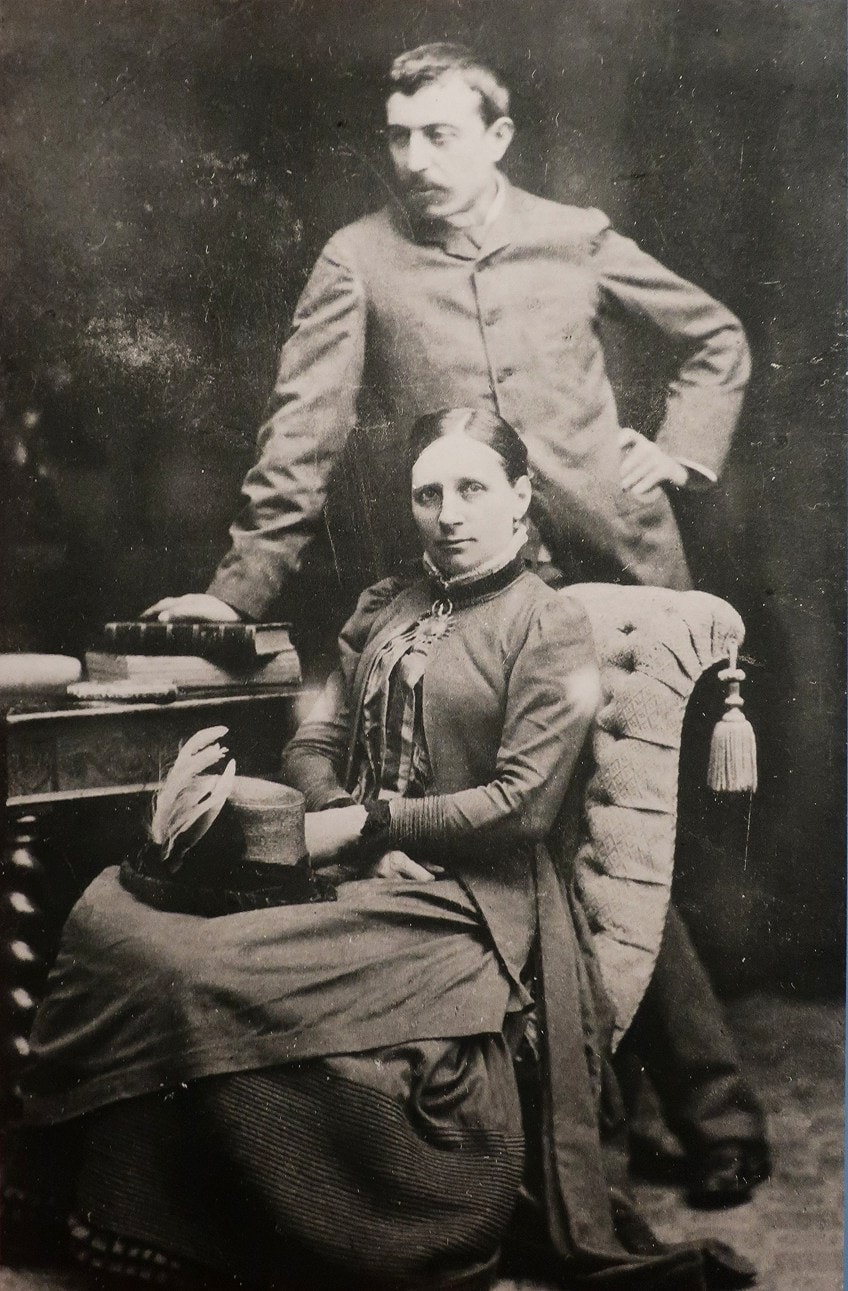

The next January, the Gauguin family relocated to Rouen, where they might reside more affordably and where he felt he had seen prospects when seeing Pissarro there the past year.

Nevertheless, the business was a failure, and before the close of the year, Mette and the youngsters had relocated to Copenhagen, with the suffering French artist following soon afterward in November of 1884, carrying his painting portfolio with him, which thereafter stayed in Copenhagen. Living in Copenhagen was equally challenging, and their relationship became tense. Paul Gauguin left for Paris the next year at Mette’s insistence and with the encouragement of her family.

Gauguin the Artist’s Return to Paris

In June 1885, Gauguin traveled to Paris with Clovis, his six-year-old son. The rest of the children stayed in Copenhagen with their mother, where they enjoyed the assistance of friends and family, while Mette found employment as an interpreter and language tutor.

Gauguin originally struggled to re-enter the Parisian art community, and he spent his first winter back in true poverty, forced to work a succession of demeaning occupations.

Clovis finally became unwell and was transferred to a private school, with monies provided by Gauguin’s sister Marie. Gauguin created relatively little work in his first year. In May 1886, he showed 19 works and a wood print at the last Impressionist exhibition. The majority of these works were older works from Copenhagen or Rouen, and there were very few innovative ideas in the few newer pieces. However, his Women Bathing (1885) established what would become a recurrent subject: the lady in the surf.

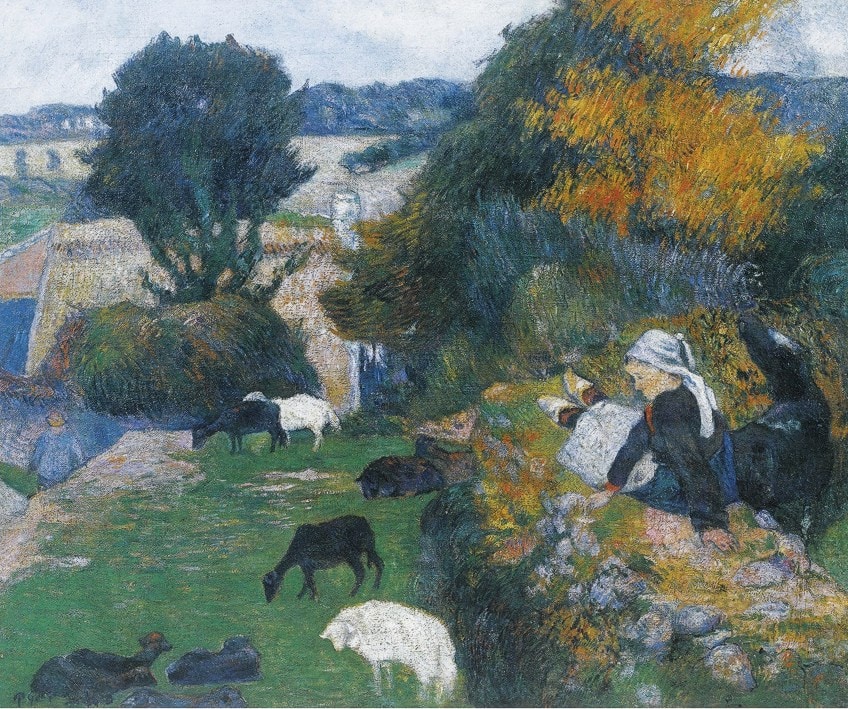

Félix Bracquemond did, however, buy one of his works. At the exhibition, Gauguin scorned Seurat’s Pointillism method and later in the year split firmly with Pissarro, who became increasingly hostile to the French artist from that moment forward. Gauguin the artist spent the summer of 1886 at the Brittany artist enclave of Pont-Aven.

He was initially drawn to the area since it was inexpensive to reside there. He did, nevertheless, find surprising favor with the youthful art pupils who gathered there throughout the summer. In the relatively easy-going beach town, his inherently combative disposition (he was an exceptional brawler and swordsman) was no hindrance. During that time, he was recognized for his unusual look as well as his work.

Among these new acquaintances was Charles Laval, who would join Gauguin to Panama and Martinique the ensuing year.

That year, he completed some pastel works of naked people in the style of Degas, which were displayed at the Impressionist exhibit in 1886. He primarily produced landscapes, including the Breton Shepherdess (1886), in which the person is secondary. In its composition and powerful use of pure hues, his Young Breton Boys Bathing (1887), which introduced a topic he revisited every time he frequented Pont-Aven, is clearly inspired by Degas.

The childlike illustrations of English cartoonist Randolph Caldecott, used to illustrate a famous reference journal on Brittany, had captured the imagery of Pont-avant-garde Aven’s academic creatives, who were eager to break free from the traditionalism of their institutions. Gauguin deliberately emulated them in his illustrations of Breton girls. Once in his Paris workshop, these ideas were developed into artworks.

The most notable of them is Four Breton Women (1886), which represents a significant break from his previous Impressionist approach while still embracing some of the naïve nature of Caldecott’s drawing, overdoing characteristics to the brink of parody.

Gauguin returned to Pont-Aven after visiting Martinique and Panama. The Pont-Aven School is distinguished by its powerful use of pure color and Symbolism. Gauguin was dissatisfied with Impressionists, believing that conventional European artwork had become too derivative and without metaphorical profundity. In comparison, he found the artwork of Asia and Africa to be full of mysterious meaning and vitality.

There was a craze in Europe at the moment for other civilizations’ artwork, particularly Japanese aesthetics.

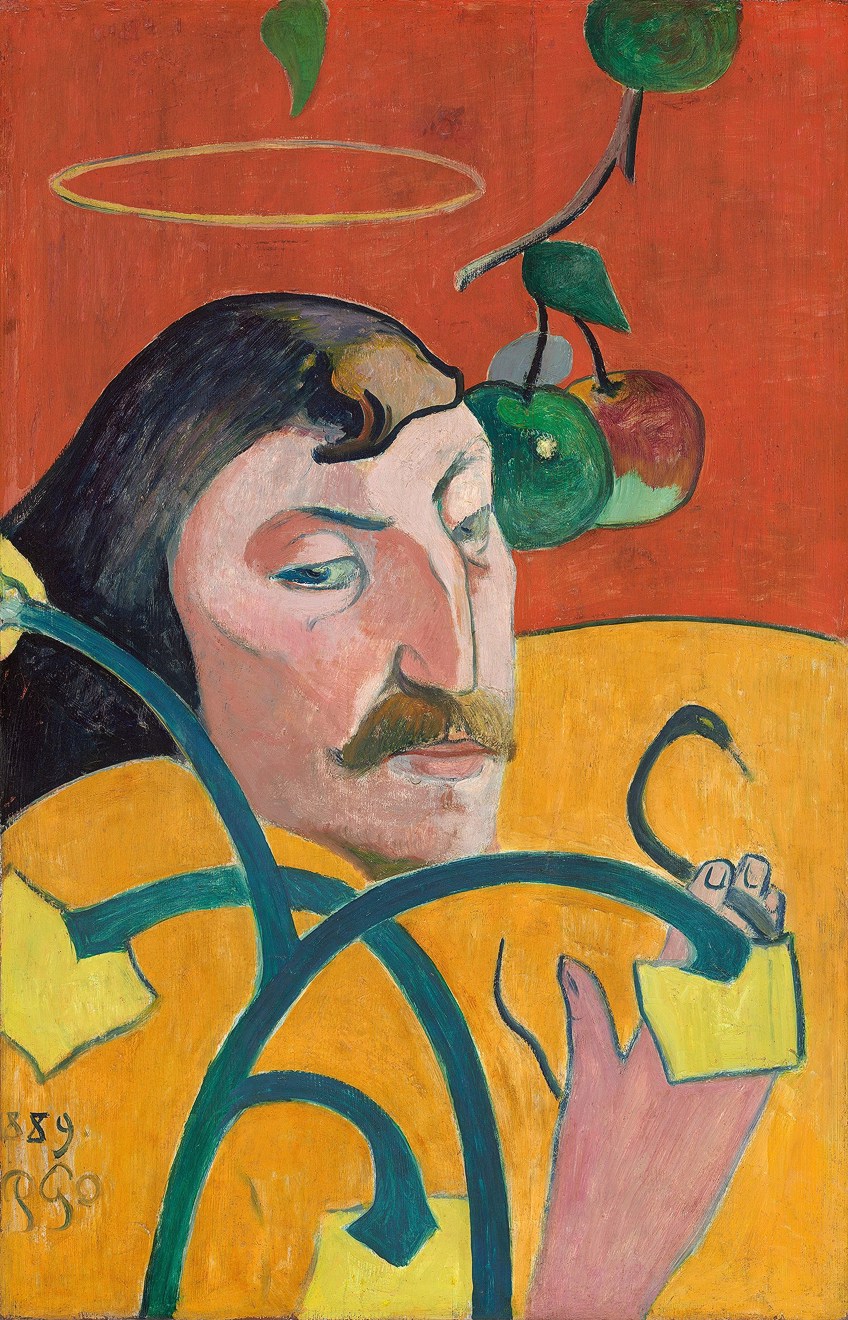

Synthetism and Cloisonnism

Gauguin’s work progressed towards Cloisonnism while influenced by Japonism and traditional folk art. The style’s name was coined by critic Édouard Dujardin to characterize Émile Bernard’s manner of creating with broad fields of color and sharp contours, which evoked in Dujardin a sense of the Middle Ages cloisonné enameling process. Gauguin admired Bernard’s painting and his bold use of a manner that matched Gauguin’s attempt to capture the spirit of the subjects in his work.

The figure was simplified to sections of pure hue divided by thick black edges in the French artist’s The Yellow Christ (1889), which is frequently recognized as a typical Cloisonnist piece. Gauguin ignored traditional perspective and aggressively abolished delicate color gradations in such paintings, thereby eschewing the two most defining characteristics of post-Renaissance art.

His art subsequently progressed into Synthetism, a style wherein neither shapes nor colors dominate, but each plays an appropriate part.

Gauguin’s Time in Martinique

After visiting Panama, Gauguin spent the summer of 1887 on the island of Martinique, escorted by his companion, the painter Charles Laval. His ideas and observations during this period are documented in correspondences to his wife Mette and painter colleague Emile Schuffenecker. He went to Martinique through Panama, where he had found himself poor and jobless.

At that period, France had a homecoming program under which if a person became bankrupt or became stuck on French territory, the government would compensate for the ship’s voyage home. Gauguin and Laval opted to disembark at the port of St Pierre after departing Panama, safeguarded by the deportation legislation. Historians dispute whether Gauguin chose to remain on the island on purpose or by chance.

During his time in Martinique, Gauguin completed 11 documented works, several of which appear to be inspired by his hut.

His letters to friends convey his enthusiasm for the region and inhabitants depicted in his works. Gauguin said that four of his artworks on the island were superior to the others. The paintings are vividly colored, carelessly drawn outdoor figural subjects. Although his stay on the island was brief, it had a significant impact. Some of his characters and drawings were reused in later works, such as the theme in Among the Mangoes (1887), which is also copied on his fans. After Gauguin departed the island, rural and native inhabitants remained prominent subjects in his paintings.

Gauguin’s Tahiti Trip

In 1890, Paul Gauguin had planned to make Tahiti his next creative location. In February of 1891, a profitable sale of artworks at the Hôtel Drouot in Paris, combined with additional activities such as a luncheon and a fundraiser performance, raised the required sums. The sale had been substantially aided by a favorable evaluation from Octave Mirbeau, whom Gauguin had pursued through Camille Pissarro. Gauguin sailed out for Tahiti on the 1st of April 1891, pledging to come back a wealthy man with a new beginning after seeing his spouse and kids in Copenhagen for what proved out to be the final occasion.

His stated intention was to flee European society and “anything unnatural and traditional.”

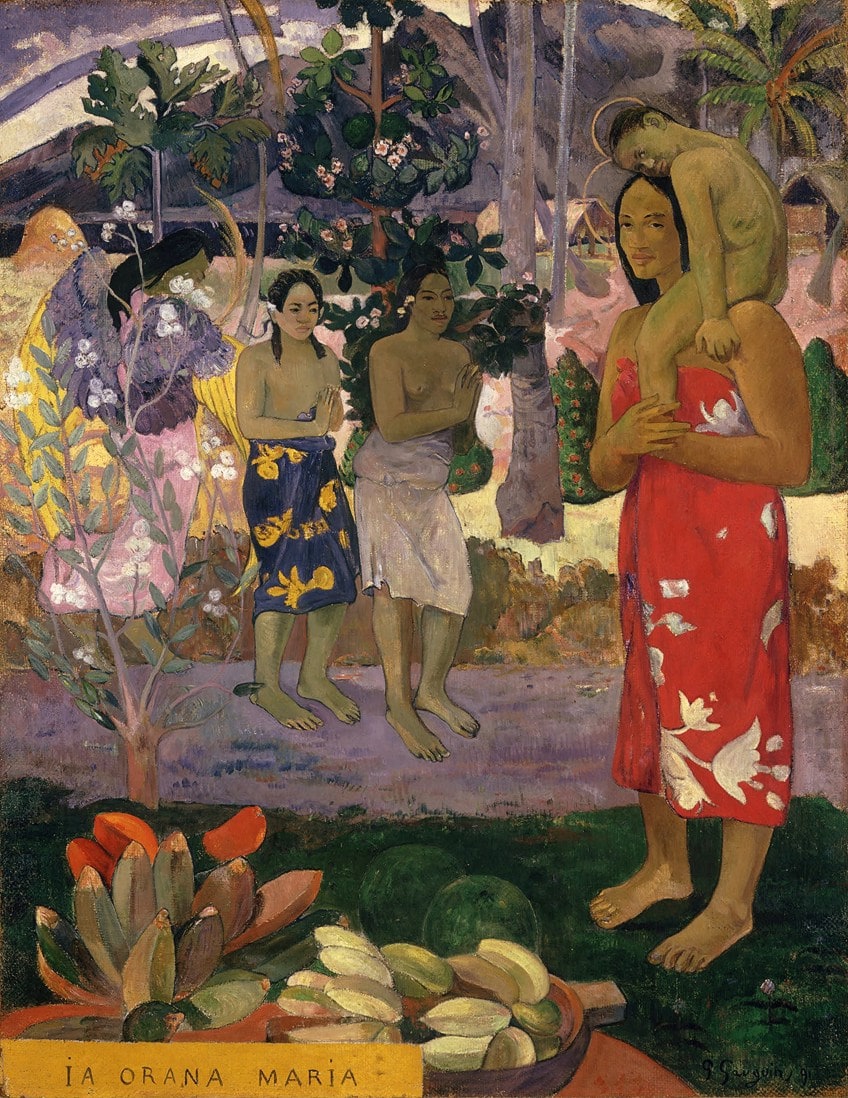

He spent the first three months at the colony’s capital of Papeete, which was already heavily impacted by Franco and European civilization. Belinda Thomson, his chronicler, says that he must have been disillusioned in his image of a primeval utopia. He couldn’t sustain the gratification-seeking lifestyle in Papeete, and his first work, Suzanne Bambridge (1891), was not well received. He opted to establish his workshop in Papeari, about 45 kilometers from Papeete, and to live in a local indigenous bamboo house. There, he painted scenes from Tahitian life such as Ave Maria (1891), which became his most cherished Tahitian work.

This is when he created several of his most beautiful paintings. His first portrait is of a Tahitian female, Woman with a Flower (1891). The picture is famous for the delineation of Polynesian characteristics. He sent the artwork to his sponsor, George-Daniel de Monfreid, an acquaintance of Schuffenecker who would become Gauguin’s ardent supporter in Tahiti.

By the end of the summer of 1892, this artwork was on show at Goupil’s gallery.

Art historians have stated that Gauguin’s meeting with exotic eroticism in Tahiti, shown in the picture, was by far the most essential component of his visit there. Gauguin sent nine works to Monfreid in Paris in total. These were finally shown in a combined exhibit with the late Vincent van Gogh in Copenhagen.

Claims that they had been favorably regarded (albeit only two of the Tahitian works were purchased, and his previous works were unfavorably contrasted with van Gogh’s) were enough to persuade Gauguin to return with the 70 additional works he had produced. In any event, he was nearly out of money, relying on a governmental subsidy for free travel back.

Furthermore, he had other medical issues that were misdiagnosed as heart difficulties by the general practitioner, which Mathews believes might have been preliminary indicators of infection. Gauguin later produced a memoir titled Noa Noa (1901), which was initially intended as a remark on his artworks and described his adventures in Tahiti.

Modern reviewers have alleged that the piece’s topics were partly fictitious and stolen.

Gauguin the Artist’s Return to France

Gauguin returned to France in August of 1893, where he proceeded to depict Tahitian subjects such as Sacred Spring, Sweet Dreams (1894). A show at the Durand-Ruel gallery in1894 was a modest sensation, with 11 of the 40 works sold at relatively high prices. He rented accommodation on the outskirts of the Montparnasse area, which is popular with painters, and began hosting a weekly seminar. He put on a foreign identity, dressed in Polynesian garb, and had a publicized romance with a young lady in her 20s, “partly Indian and partly Malayan, known as Annah.”

Despite the mild success of his November show, he later lost Durand-support Ruel’s for unknown reasons. According to Mathews, this is a catastrophe for Gauguin’s career. Among many other matters, he missed out on an entrée to the marketplace in America. At the start of 1894, he was producing woodcuts for his projected guidebook using an innovative approach. For the summer, he traveled to Pont-Aven. In February of 1895, he tried another sale of his artworks at the Hôtel Drouot in Paris, comparable to the piece he had created in 1891, but it failed.

By this point, it was evident that he and his wife were no longer together. Despite initial signs of reunion, they rapidly clashed over finances and neither contacted the other.

Gauguin first declined to distribute any of his uncle Isidore’s fortune, which he had received immediately after his arrival. Mette was finally given a portion of the inheritance, but she was enraged and continued to communicate with Gauguin only via Schuffenecker, which was more irksome for Gauguin because his confidant now understood the whole depth of his treachery. Attempts to obtain cash for Gauguin’s journey to Tahiti had proven unsuccessful by the middle of 1895, and he started taking assistance from acquaintances.

Gauguin never returned to Europe after a friend secured an inexpensive trip back to Tahiti in June of that same year.

Paul Gaugain’s Return to Tahiti

Gauguin landed in September of 1895 and spent the following six years enjoying a seemingly happy existence as an artist near Papeete. Throughout this period, he managed to sustain himself by an expanding constant stream of purchases and the generosity of acquaintances and supporters, but there was a brief period in 1899 when he was obliged to accept an office job in Papeete, of which there is little trace.

He erected a big reed and thatch home in Puna’auia, a rich location close to Papeete, in which he constructed a big workshop with no expenditure spared.

For at least the first year, he created no artworks, assuring Monfreid that he intended to focus on sculpting from then on. Few of his woodcarvings from this era have survived, the majority of which were gathered by Monfreid, such as Christ on the Cross, a wooden cylindrical sculpture with an unusual mixture of spiritual symbols.

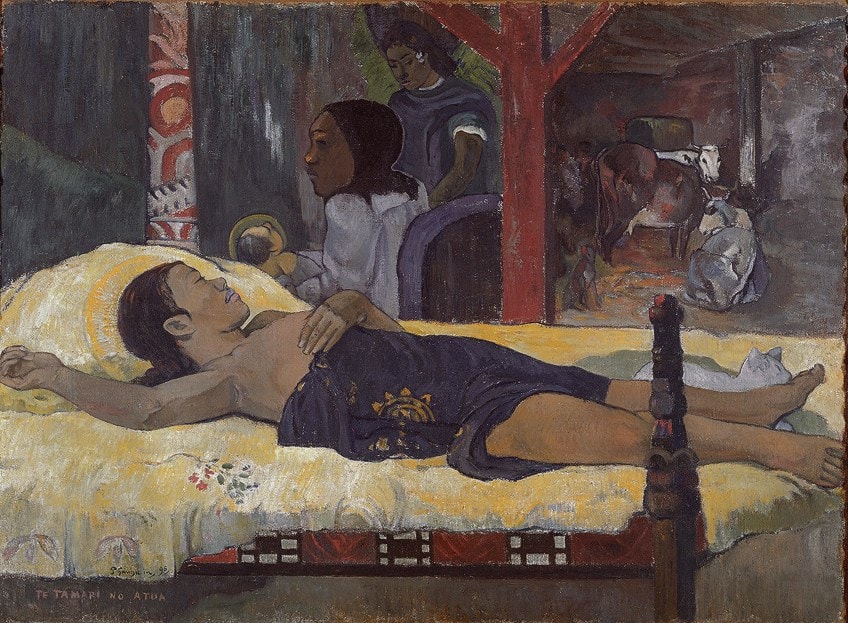

Similar metaphorical decorations in Brittany, such as at Pleumeur-Bodou, where ancient menhirs have been Christianized by local artisans, may have influenced the cylinder. When he returned to art, it was to resume his long-running sequence of overtly loaded nudes in works like Son of God (1896).

Scholars observe a reversion to Christian iconography that would have appealed to the settlers of the period, who were eager to maintain what remained of indigenous cultures by emphasizing the transcendence of religious values.

Gauguin was targeting an assembly of fellow settlers in Papeete in these works, not his prior nouvelle crowd in Paris. His health began to deteriorate, and he was hospitalized multiple times for a variety of diseases.

While in France, he injured his ankle in a boozy scuffle during a seashore excursion to Concarneau. The wound, an exposed fracture, never fully healed. Then severe and agonizing blisters began to sprout up and down his legs, restricting his movement. Arsenic was used to treat them.

Gauguin attributed the lesions to the tropical heat and called them “eczema,” but his novelists think it was the progression of syphilis. Gauguin was not able to pursue his pottery work in the islands because sufficient clay was unavailable. Likewise, because he did not have access to a press, he was forced to use the monotype method in his visual works.

Surviving specimens of these prints are extremely scarce and fetch exorbitant sums in an auction.

The French Artist’s Time in the Marquesas Islands

Since discovering a series of finely crafted Marquesan vases and swords in Papeete in his first weeks in Tahiti, Gauguin had nourished his ambition to settle in the Marquesas. He did, however, discover a community that, like Tahiti, had lost its culture and character. The Marquesas were the most afflicted by the introduction of Western illnesses of any Pacific main islands. He purchased a parcel of property in the town center from the religious ministry after first becoming acquainted with the parish priest by attending service on a frequent basis.

This bishop originally favored Gauguin because he was cognizant that Gauguin had supported the Catholic church in Tahiti through his writings.

Gauguin preferred to create vistas, still lifes, and character studies for Vollard’s customers at this period, eschewing the primal and forgotten paradise motifs of his Tahiti works. However, there is a large trio of images from this recent era that indicate greater issues. Young Girl with Fan (1902) is the first of them.

Gauguin’s condition started to worsen again about the same period, with the same typical cluster of problems comprising leg pain, irregular heartbeat, and overall infirmity. The discomfort in his wounded ankle became unbearable, and in July he was forced to rent a trap from Papeete so he could get around town.

By September, the agony had become so severe that he had to resort to morphine shots.

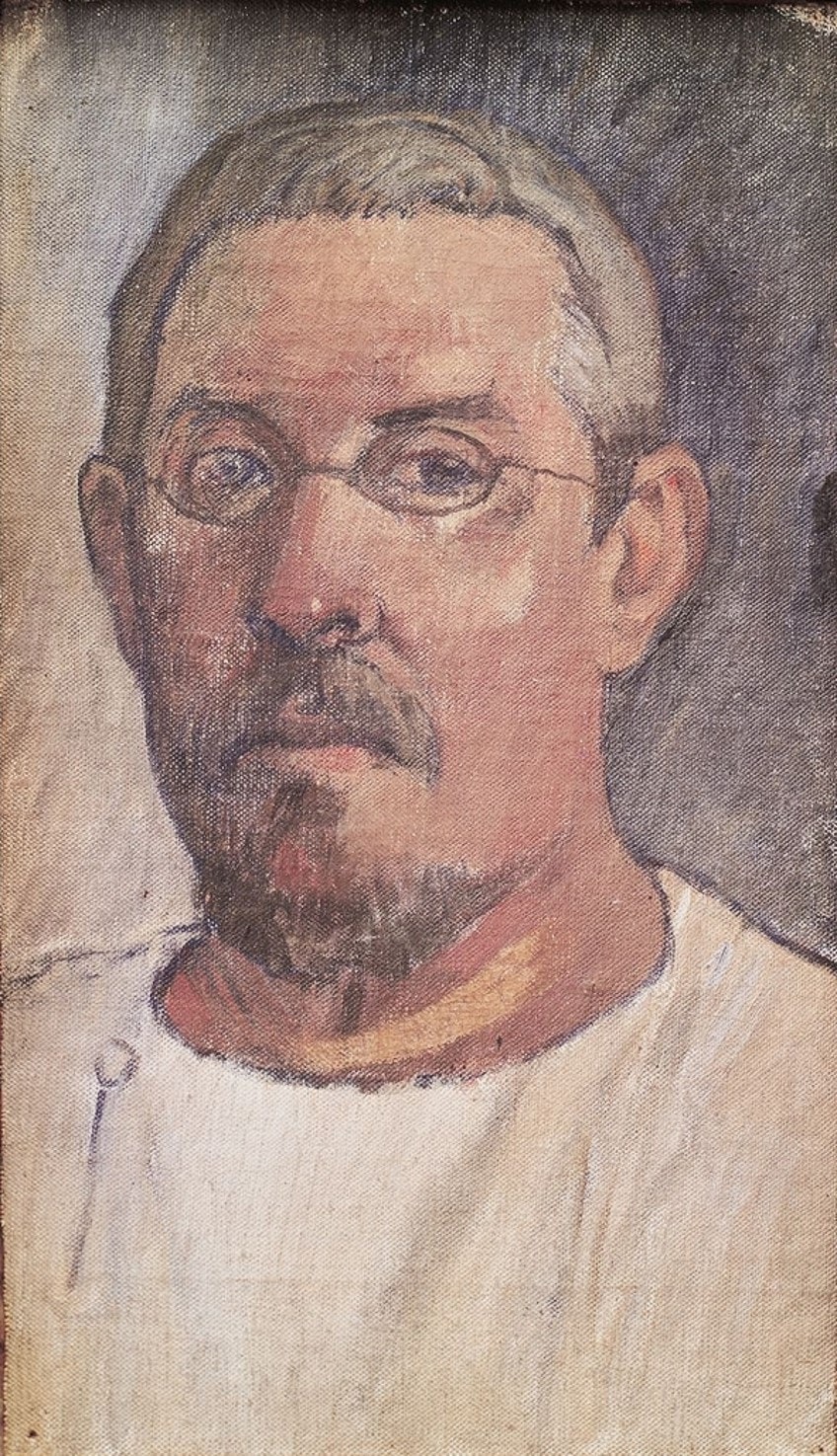

However, he was worried enough about the addiction he was building that he handed up his needle set to a neighbor, instead of depending on laudanum. His vision was also failing him, as seen by the glasses he sports in his last known Self Portrait (1903). This was originally a portrait started by a friend that he finished himself, which explains the unusual style. It depicts a man who is exhausted and old, but not completely crushed. For a time, he pondered traveling to Europe, namely to Spain, to seek therapy.

Gauguin launched a crusade at the start of 1903 to expose the ineptitude of the island’s security forces, particularly Jean-Paul Claverie, for taking the side of the indigenous straight in a case concerning the apparent intoxication of a number of them. Claverie, on the other hand, evaded punishment.

Gauguin responded to the governor, François Picquenot, in early February, claiming fraud by one of Claverie’s employees. Picquenot examined the accusations but was unable to corroborate them.

Claverie’s response was to file a case against Gauguin. On March 27, 1903, he was fined and ordered to three months in imprisonment by the magistrate judge. Gauguin promptly launched a protest in Papeete and began fundraising to fly to Papeete to witness his case. Gauguin was quite frail and in a lot of agony at the time, so he turned to morphine once more. On the 8th of May, 1903, he passed unexpectedly.

Gauguin’s Historical Significance

Primitivism was a late-19th-century art style distinguished by accentuated body structure, animal symbols, geometric motifs, and harsh contrasts. Paul Gauguin was the first painter to methodically employ these qualities and win widespread popular acclaim.

The European artistic elite, encountering for the first occasion the artwork of Africa, Asia, and Native Americans, were captivated, interested, and enlightened by the freshness, unpredictability, and raw strength contained in the artwork of those other regions.

Gauguin, like Pablo Picasso in the early 20th century, was motivated and driven by the raw strength and purity of those other nations’ so-called Primitive Art. Gauguin is regarded as a post-Impressionist artist. His vibrant, vivid, and design-oriented works had a tremendous impact on Modern art. Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, Vincent van Gogh, Henri Matisse, and many more were among the painters and groups influenced by him in the early 20th century.

Gauguin the Artist’s Style and Technique

Gauguin used a method referred to as peinture à l’essence. The oil is emptied from the pigment, and the residual pigment muck is combined with a solvent. He may have used a comparative idea in creating his monotypes, but instead of metals, he used sheet, which absorbs oil and gives the finished pictures the matte aspect he intended. He also used glass to test some of his pre-existing works, reproducing an underside picture onto the glass surface using watercolor or gouache for print.

Gauguin’s woodcuts were no less inventive, especially when compared to the avant-garde painters who were accountable for the woodcut resurgence that was taking place at the time.

Rather than incising his block with the intention of creating a precise drawing, Gauguin chiseled them in a way comparable to wood sculpting, accompanied by sharper tools to produce texture and tone inside his strong shapes. Many of his instruments and strategies were regarded as novel. This style and use of spaces ran parallel to his flat, ornamental relief paintings.

Some of Gauguin the Artist’s Most Famous Works

Paul Gauguin created many artworks. Unfortunately, he only became known after his death. Let us look at some of his most famous works:

- Tahitian Women on a Beach (1891)

- Vision After the Sermon (1888)

- Two Tahitian Women (1899)

- Hail Mary (1891)

- Nafea Faa Ipoipo? (When Will You Marry?) (1892)

Further Reading

Who is Paul Gauguin and how did Paul Gauguin die? We have answered those questions, but what if there is more you want to learn about Gauguin the artist? We have compiled a list of some informative books to help you learn more.

Gauguin: Metamorphoses (2014) by Starr Figura

Metamorphoses delves into the amazing link that exists between Paul Gauguin’s uncommon and exceptional prints and transfer sketches and his more well-known pieces of art in wood and ceramics. These impressive works, generated in several distinct bursts of action from 1889 until his death, represent Gauguin’s experimentations with a variety of media, ranging from drastically “primitive” woodblock prints that expanded from the sculptural overcharging of his hand-carved reliefs to jewel-like gouache monotypes and large strange transfer illustrations. Gauguin’s artistic method frequently entailed repeating and reconstituting important ideas from one work to the next, enabling them to metamorphosis through time and materials.

- Exploring the relationship between Gauguin's drawings and paintings

- Looking at the artist's experimental approach to techniques

- How Gauguin's use of other media inspired his creativity

Savage Tales: The Writings of Paul Gauguin (2019) by Linda Goddard

An innovative examination of Gauguin’s texts, revealing their vital importance in his creative practice and imperial identification conflict. Paul Gauguin, a French artist who resided in Polynesia, plays an important role in the history of Western primitivism. This is the first volume dedicated entirely to his diverse literary work. It examines his original manuscripts, some of which are lavishly illustrated, and reintroduces them as a vital component of his work. Gauguin’s writings’ ostensibly chaotic, collage-like form allowed him to reflect the “primitive” culture he admired while disregarding the manner of establishment criticism.

- An original study of Gauguin’s writings and their role in his art

- The first book devoted to Gauguin's wide-ranging literary output

- This analysis enriches our understanding of Gauguin and his art

And with that, we have come to the close of our look at Paul Gauguin’s Biography and artwork. Paul Gauguin is a notable French painter who was initially trained in Impressionism but drifted away from its obsession with the ordinary world to establish a distinct form of artwork known as Symbolism. Gauguin dabbled with new color concepts and semi-decorative techniques to create as the Impressionist style came to a close in the late 1880s. He notably collaborated with Vincent Van Gogh in southern France for one summer in an incredibly colorful manner before abandoning Western civilization totally.

Take a look at our Paul Gauguin paintings webstory here!

Frequently Asked Questions

Who Is Paul Gauguin?

Gauguin considered his paintings as a philosophical reflection on the ultimate purpose of human life, pursuing the type of direct engagement to the natural environment that he experienced in diverse villages of French Polynesia and other non-western civilizations. He also recognized the prospect of religious satisfaction and solutions to questions about how to live more in tune with nature. During the later decades of the 19th century, Gauguin was a significant member of a Western cultural trend known as Primitivism.

How Did Paul Gauguin Die?

Gauguin suffered many ailments, including that of his heart and syphilis. Gauguin was quite frail and in a lot of agony at the time, so he turned to morphine once more. On the 8th of May, 1903, he passed unexpectedly.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Paul Gauguin – Influential Primitivist Post-Impressionist.” Art in Context. November 17, 2021. URL: https://artincontext.org/paul-gauguin/

Meyer, I. (2021, 17 November). Paul Gauguin – Influential Primitivist Post-Impressionist. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/paul-gauguin/

Meyer, Isabella. “Paul Gauguin – Influential Primitivist Post-Impressionist.” Art in Context, November 17, 2021. https://artincontext.org/paul-gauguin/.