Édouard Manet – The Godfather of Modernism

Édouard Manet the artist was a French Impressionist who was renowned for painting scenes of contemporary life. Manet was raised in the upper classes yet enjoyed a bohemian lifestyle. Manet’s paintings astounded the French Salon audience with their contempt for scholarly traditions and stunningly contemporary depictions of city life. Olympia (1863) and Le déjeuner sur l’herbe (1863), two of his early masterpieces, sparked heated debate and functioned as uniting grounds for the new artists who would develop the French Impressionist movement.

The Life and Art of Édouard Manet

Édouard Manet’s paintings have long been connected with the French Impressionists; he was undoubtedly a major influencer on them, and he learned a great deal from them in return. Nevertheless, in recent times, experts have recognized that he also learned from his French counterparts’ Naturalism and Realism, as well as 17th-century Spanish art. This dual fascination in Old Masters and modern Realism laid the groundwork for his unique style. But when was Édouard Manet born, and how did he rise to fame? It is best to begin with his early life.

| Date of Birth | 23 January 1832 |

| Date of Death | 30 April 1883 |

| Place of Birth | Paris, France |

| Associated Movements | Impressionism, Realism |

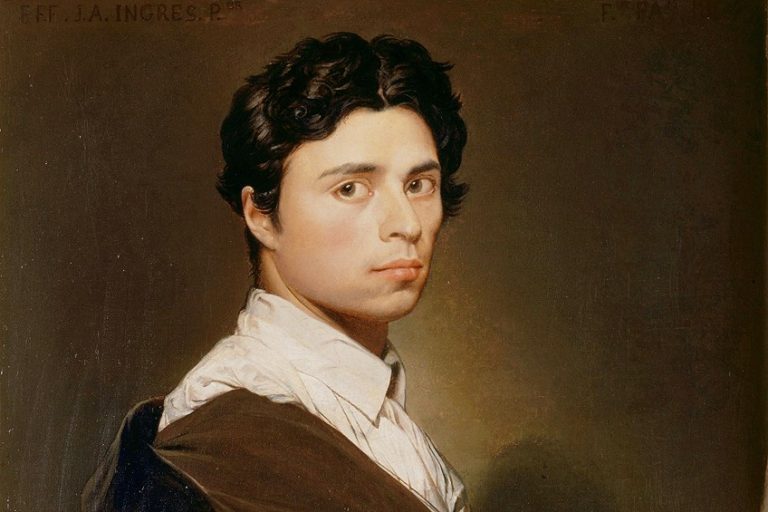

The Early Years of Édouard Manet

Édouard Manet was born on the 23rd of January, 1832, in Paris, in the old family residence on the rue Bonaparte, to a wealthy and well-connected household. His mother was a diplomat’s daughter, and his father was a magistrate who wanted Édouard to go into the legal practice. His uncle urged him to paint and accompanied him to the Louvre as a teenage boy. In 1841, he enlisted in the Collège Rollin, a secondary school. On the recommendation of his uncle, Manet joined a specialized sketching class in 1845, when he met Antonin Proust, who would become his longtime friend and the future Minister of Fine Arts in France.

In 1848, at his father’s recommendation, he traveled to Rio de Janeiro aboard a training ship. After he flunked the Navy admissions test repeatedly, his father gave in to his desire to undertake an art education. Manet trained under academic artist Thomas Couture from 1850 until 1856. Manet spent his leisure time copying the Old Masters at the Louvre.

Manet traveled to Italy, Germany, and the Netherlands from 1853 to 1856, when he was inspired by Dutch artist Frans Hals and Spanish painters Francisco José de Goya, and Diego Velázquez.

The Career of Édouard Manet the Artist

Manet established a studio in 1856. During this time, his approach was defined by fluid brushstrokes, the reduction of features, and the rejection of transitory tones. Embracing Gustave Courbet’s contemporary realism approach, he produced The Absinthe Drinker (1859) and other contemporaneous themes like the homeless, performers, Romani, individuals in cafés, and bullfighting. He seldom produced religious, mythical, or historic themes beyond his formative years; for instance, Christ Mocked (1865).

In 1861, the artist had two artworks approved at the Salon. Critics panned a painting of his parents, who were paralyzed and speechless at the time due to a stroke. While another, The Spanish Singer (1860), was appreciated by Théophile Gautier and was put in a more prominent area because of its appeal among Salon-goers. Several young painters were drawn to Manet’s work because it seemed “somewhat haphazard” in comparison to the precise manner of so many other Salon works.

“The Spanish Singer”, rendered in a “weird new way,” opened many artists’ eyes.

A year after his father died in 1862, Manet wedded Suzanne Lehnhoff. She was a Dutch piano instructor two years older than Manet and had been intimately connected with him for around 10 years. Lehnhoff was first hired by Manet’s father to teach Manet and his siblings to play the piano. Among other works, Manet portrayed his wife in The Reading (1873). Leon Leenhoff, Suzanne’s son, frequently appeared for Manet. He is well known as the basis of the 1861 painting The Boy Carrying a Sword. He also appears in The Balcony (1869) as the child bringing a tray in the backdrop.

Through another artist, Berthe Morisot, who was a fellow of the group and pulled him into their practices, Manet made acquainted with the Impressionists, Claude Monet, Edgar Degas, Alfred Sisley, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Paul Cézanne, and Camille Pissarro. These artists were thereafter known as the Batignolles group. Morisot, the presumed grand-niece of artist Jean-Honoré Fragonard, got her first picture approved at the Salon de Paris in 1864, and she proceeded to exhibit there for the following 10 years.

In 1868, Manet became Morisot’s companion and coworker. She is attributed for persuading Manet to try en plein air art, which she had been doing since being exposed to it by another of her friends, Camille Corot. They had a mutually beneficial connection, and Manet used some of her methods in his works. When she wedded his brother, Eugène, in 1874, she became his sister-in-law. In contrast to the rest of the Impressionists, Manet believed that contemporary painters should strive to display their works at the Paris Salon.

Nonetheless, when Manet was denied admission to the International Display of 1867, he organized his own exposition.

His mother was concerned that he would spend all of his fortunes on this massively costly undertaking. While the show received mixed reviews from the main critics, it did offer him his initial meetings with a number of future Impressionist artists, notably Edgar Degas. Despite the fact that his work inspired and predicted the Impressionist style, Manet avoided participating in Impressionist shows, largely because he did not want to be considered as the spokesman of a collective identity, and partially because he wanted to exhibit at the Salon. Eva Gonzalès, the author Emmanuel Gonzalès’s daughter, was his sole official student.

The Impressionists, particularly Morisot and Monet, impacted him. Their impact may be seen in Manet’s use of lighter shades: from the early 1870s, he used fewer dark backgrounds but preserved his unique use of black, which was unusual for Impressionist painting. He painted several paintings in the open air (en plein air), yet he always reverted to what he regarded as significant studio work.

Manet had a strong acquaintance with musician Emmanuel Chabrier, for whom he painted two portraits; the musician bought 14 of Manet’s works and devoted his Impromptu to Manet’s wife.

At the start of the 1880s, one of Manet’s regular subjects was Méry Laurent, who appeared in seven pastel paintings. Laurent’s salons entertained many French authors and artists of the day, and it was through such occasions that Manet gained contacts and influence. Throughout his life, despite opposition from art critics, Manet had defenders in the form of Émile Zola, who openly backed him in the media, and Charles Baudelaire, who urged him to represent life as it was. Manet sketched or painted them both as well.

Late Works and Death

Manet’s health deteriorated in his mid-40s, and he acquired terrible discomfort and partial immobility in his legs. In 1879, he began taking therapies at a clinic near Meudon to cure what he thought was a circulatory ailment, but he was actually suffering from a recognized side effect of syphilis. He created a picture of the opera diva Émilie Ambre as Carmen there in 1880. Ambre and her boyfriend Gaston de Beauplan had a Meudon estate and in December of 1879, they staged the first showing of Manet’s The Execution of Emperor Maximilian (1868) in New York.

Manet created several small-scale still lifes of vegetables and fruits in his latter years, including The Lemon (1880) and A Bunch of Asparagus (1880). Un Bar aux Folies-Bergère, his final significant piece, was created in 1882 and shown in the Salon that year. Following it, he restricted himself to tiny forms. His final works were depictions of flowers in glass pots. His left foot was removed in April 1883 owing to gangrene caused by rheumatism. On the 30th of April, he died in Paris. His body was laid to rest in the city’s Passy Cemetery.

Édouard Manet’s Artworks and Techniques

Manet’s modernism stems mostly from his ambition to modernize earlier forms of paintings by introducing new content or modifying traditional components. He did it with an acute awareness of both historic traditions and modern reality. This was definitely the origin of many of the scandalous rumors he ignited. He is attributed for promoting the alla prima painting method. Rather than layering colors, Manet would instantly lay down the hue that best suited the final impact he desired.

The Impressionists popularized the technique, finding it admirably suited to the requirements of capturing effects of light and atmosphere when painting outside.

This flattening, as opposed to its naturalism, may have represented popular advertisements or the artifice of art in the creator’s day. This feature is now regarded by critics as the first instance of “flatness” in contemporary art. Manet’s painting approach may be seen early in Music in the Tuileries (1862).

It is a foreshadowing of his ongoing fascination with the theme of pleasure, inspired by Velázquez and Hals. While some thought the painting was incomplete, the projected mood conveyed a feeling of what the Tuileries grounds were like at the time; one can envision the songs and discussion. Manet depicts his colleagues, painters, writers, and performers who are there, as well as a self-portrait among the group.

Influential Works That Display Manet’s Best Artistic Characteristics

Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe (1863) is a significant early work. In 1863, the Paris Salon denied it for display, but Manet consented to show it at the Salon des Refusés, a concurrent exhibit to the authorized Salon, in the Palais des Champs-Elysées as an unofficial exposition. Emperor Napoleon III established the Salon des Refusés to address an issue that arose after the Salon’s Judging Panel refused 2,783 artworks out of a total of 5000 that year. Every disqualified artist may choose whether or not to show at the Salon des Refusés; fewer than 500 of the failed artists decided to do so.

Manet frequently used his wife Suzanne, Ferdinand Leenhoff, and a model by the name of Victorine Meurent to pose for paintings. Meurent subsequently sat for many more of Manet’s significant works, including Olympia, and she had established herself as a capable painter in her own right by the mid-1870s. The contrast of fully dressed men and a naked lady in the picture was contentious, as was its short, sketch-like approach, which separated Manet from Courbet.

Simultaneously, Manet’s arrangement reflects his studies of the great masters.

Scholars identify Pastoral Concert (1510) and The Tempest (1508) as key antecedents for Le déjeuner sur l’herbe, both of which are credited to Italian Renaissance painters Titian and Giorgione, respectively. The Tempest is a mysterious picture that depicts a fully dressed man and a naked lady in a rural area. The gentleman is standing to the left and looking to the side, evidently at the lady, who is sitting and nursing a baby; the two characters’ connection is unknown. In Pastoral Concert, two dressed males and a naked lady sit on the lawn, creating music, as another naked woman stands alongside them.

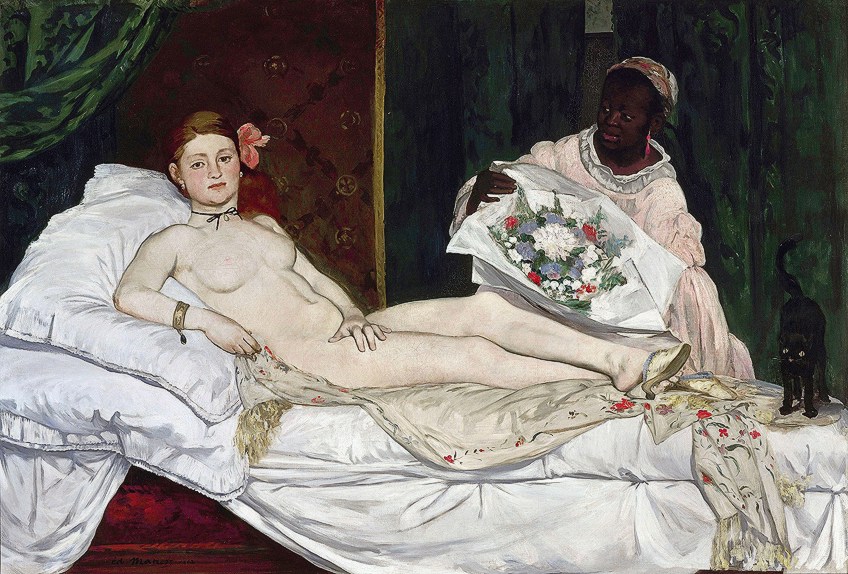

In the work Olympia (1863), Manet, like in Le déjeuner sur l’herbe, imitated a celebrated Renaissance artist’s oeuvre, depicting a naked woman in a style evocative of earlier studio pictures, but whose position was modeled on Titian’s Venus of Urbino (1538). Manet began work on the painting after being encouraged to present a naked painting to the Salon.

His candid image of a self-assured harlot was approved by the Paris Salon in 1865, causing a stir.

Only the administration’s safeguards stopped the artwork from being pierced and ripped” by upset onlookers. The artwork was contentious partly due to the fact that the naked woman was wearing minor pieces of clothes, such as a flower in her tresses, a bracelet, a ribbon around her throat, all of which emphasized her nudity, sensuality, and luxurious lifestyle.

At the time, the orchid, and the black cat were all acknowledged emblems of sexuality. The body of this contemporary Venus is slender, contrary to popular belief; the artwork’s lack of purity irritated observers. The flatness of the picture, influenced by Japanese woodblock artwork, helps to render the naked figure more human and less sensual. A fully clothed black maid appears, capitalizing on the then-current idea that African folks were hyper-sexed.

The fact that she is dressed as a maid to a harlot heightens the painting’s sexual intensity.

Olympia’s physique and eyes are brazenly confronting. She boldly stares out as one of her male suitors’ servants hands her flowers. Despite the fact that her hand is resting on her leg, concealing her pubic area, the reference to conventional feminine virtue is satirical; a sense of modesty is conspicuously lacking in this painting. Olympia’s physique and eyes are brazenly confronting. She boldly stares out as one of her male suitors’ servants hands her flowers.

Despite the fact that her hand is resting on her leg, concealing her pubic area, the reference to conventional feminine virtue is satirical; a sense of modesty is conspicuously lacking in this painting. A contemporaneous reviewer criticized Olympia’s “flagrantly contracted” left hand, which he saw as a mocking of Titian’s Venus loosened, protecting hand. Similarly, the attentive black cat at the bottom of the bed conveys a passionately defiant tone in juxtaposition to Titian’s depiction of the deity in his Venus of Urbino (1538).

Manet’s Café Scenes

French Impressionist Édouard Manet’s paintings of café settings are reflections of 19th-century Parisian human society. People are shown sipping beers, enjoying music, mingling, reading, and resting. Many of these works were inspired by drawings done on the spot. Manet frequently attended the Brasserie Reichshoffen where he based his painting At the Café (1879).

A group of individuals has gathered at the bar, and one lady approaches the spectator while others wait to be seated. Such representations are reminiscent of a flâneur’s painted notebook. These are produced in a freestyle reminiscent of artists such as Velázquez and Hals, yet they convey the spirit and vibe of Parisian evenings.

They have studied paintings of bohemianism, working-class folk, and some aristocracy.

A gentleman smokes in the nook of a Café-Concert while a waiter delivers beverages behind him. In The Beer Drinkers (1878), a lady drinks her beverage with a companion. A sophisticated gentleman sits at a bar in Corner of a Café-Concert (1879), depicted at right, while a server stands stubbornly in the backdrop, consuming her drink.

In The Waitress (1879), a serving lady lingers for a minute behind a seated client smoking tobacco, while a ballerina is on stage in the backdrop, arms outstretched as she prepares to spin. Manet also dined at Pere Lathuille, which offered a patio in conjunction with a dining room. Chez le père Lathuille (1879), one of the works he created here, depicts a man’s romantic feelings for a woman seated nearby.

Manet’s Social Activity Artworks

Manet depicted the upper class participating in more traditional social events. Manet depicts a vibrant mass of individuals celebrating a party in Masked Ball at the Opera (1873). Men wear top hats and long black coats while conversing with ladies dressed in elaborate costumes and masks. In this painting, he inserted pictures of his acquaintances.

His work The Luncheon (1868) was posed in the Manor house’s dining room. Other common hobbies were featured in Manet’s art. A unique viewpoint is used in The Races at Longchamp (1866) to emphasize the intense energy of racehorses as they sprint at the spectator. Manet depicts a well-dressed lady in the front of Skating (1877), as others skate around her.

There is always a feeling of busy urban activity running behind the image and going beyond the frame of the painting.

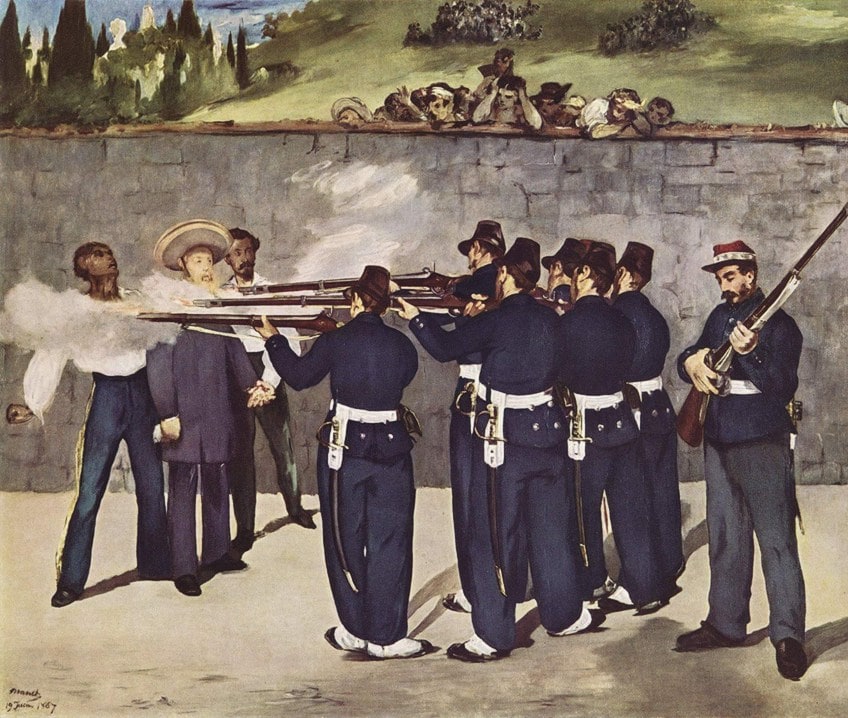

Manet’s Paintings about War

Manet’s answer to contemporary civilization includes works about conflict, which may be considered as updated versions of the category of “paintings.” The first picture was The Battle of the Kearsarge and the Alabama (1864), a maritime conflict from the American Civil War and perhaps which the painter might have observed.

The French intervention in Mexico piqued Manet’s interest next; from around 1867 until 1869, he produced three renditions of Emperor Maximilian’s death, an event that prompted worries about French domestic and international affairs. The various variations of the Execution are among Manet’s biggest works, indicating that the topic was significant to the artist. Its topic is the killing of a Habsburg monarchy established by Napoleon III by a Mexican death squad.

In France, however, neither artworks nor a print of the theme was authorized to be exhibited.

“I haven’t ever envisioned that France could be defined by such senile old buffoons, not with the exception of that tiny dimwit Thiers,” he chose to write to his companion Félix Bracquemond in Paris about his trip to Bordeaux, where Émile Zola presented him to the locations. If this was perceived as sympathy for the Commune, a subsequent letter to Bracquemond clarified his position:

“Only career politicians and the greedy, the Henrys of this earth treading on the footsteps of the Milliéres, the hideous mimics of the Commune of 1793…” He recognized Lucien Henry as a previous artist’s model and Millière as an insurance salesman “What a boon to the artists all these savage shenanigans are! But there is one silver lining to our miseries: we are not politicians and have no ambition to get voted as representatives “.

Manet’s Parisian Paintings

In his paintings, Manet painted various sights from Paris’s streets. The Rue Mosnier Decked with Flags (1878) painting displays white, red, and blue flags adorning houses along either side of the avenue; another picture with the identical title portrays a one-legged person arriving on crutches. Rue Mosnier with Pavers (1878) depicts the very same road but in a distinct situation, with laborers repairing the road while pedestrians and horses pass by.

In 1873, The Railway was produced. The scene in the late-19th-century metropolitan environment of Paris. In his most recent portrait of her, Victorine Meurent, who previously modeled for Olympia, sits in front of an iron fence, clutching a dog and an open book in her lap. A tiny girl stands next to her, her back to the artist, observing a train move under them.

Manet chooses an iron grating that “confidently sweeps over the painting” as the backdrop for an outdoor scene rather than the conventional natural vista.

The train’s sole trace is a white puff of smoke. Modern residential structures may be seen in the distance. The foreground is compressed into a tight focus in this composition. The conventional deep space standard is disregarded.

Historian Isabelle Dervaux describes the reaction to this picture when it was initially shown at the official Paris Salon in 1874: “Guests and reviewers found the topic perplexing, the arrangement confused, and the workmanship shaky. Caricaturists mocked Manet’s painting, which only a few acknowledged as the emblem of modernism that it is today. ” In 1874, Manet painted numerous watercraft scenes. Boating (1874) embodies the principles Manet gained from Japanese art in its succinctness, and the sudden clipping by the frame of the vessel and sail contributes to the image’s urgency.

The Legacy of Édouard Manet

Manet’s professional vocation spanned from 1861, the year of his first Salon appearance, through his death in 1883. Historians documented his known existing works in 1975, and they include 90 pastels, 429 oil paintings, and almost 400 artworks on paper. Despite harsh criticism from reviewers who blasted its lack of traditional finish, Manet’s work had supporters from the start. Émile Zola, for example, said in 1867:

“We’re not used to witnessing such plain and simple renderings of truth. Then, as I mentioned, there’s this really graceful awkwardness… it’s a genuinely pleasant experience to ponder this dazzling and serious artwork that depicts nature with soft cruelty.”

Manet’s paintings were considered uniquely contemporary, with a harsh painted technique and photographic lighting that was an affront to the Renaissance masterpieces he imitated or utilized as source material. He abandoned the approach he learned at Thomas Couture’s school, in which a picture was built up through consecutive layers of paint on a dark basis, in favor of a straight, alla prima style employing opaque paint on a light ground. This process, which was novel at the time, allowed for the finishing of work in a single session. It was popularized by the Impressionists and became the standard way of painting with oils for centuries to come.

Beatrice Farwell, an art historian, believes Manet “has long been considered as the Godfather of Modernism. Manet was one of the first to take considerable chances with the public’s approval, the first to make alla prima artwork the normal method for painting with oils, and among the first to experiment with the Renaissance viewpoint and provide “clean artwork” as a form of aesthetic enjoyment.

He was a forerunner, together with Courbet, in rejecting humanist and historic topics, and he and Degas were instrumental in establishing modern urban life as a suitable material for “great art.”

List of Famous Artworks

Manet produced over 430 paintings in his lifetime. However, some of these artworks became very popular over the ages. Here is our list of some of the artist’s most famous artworks.

- Le Dejeuner sur l’Herbe (1863)

- Olympia (1863)

- The Execution of Emperor Maximilian (1868)

- Railway (1873)

- Boating (1874)

- Rue Mosnier with Pavers (1878)

- A Bar at the Folies-Bergere (1882)

Recommended Reading

Today we have looked at the life and art of Manet. However, there is only so much information that one can fit into a single article. Perhaps you would like to explore the artist’s work and biography even further. Therefore, we have compiled a list of books that you might enjoy pertaining to the subject. Here are our top picks.

The Lost Notebook of Édouard Manet: A Novel (2021) by Maureen Gibbon

This beautiful historical book imagines Édouard Manet’s final days in an evocative picture of talent, disease, and the dying embers of desire, set in the brilliantly portrayed art world of 19th century Paris. As he nears the end of his life, experiencing the effects of syphilis, Édouard Manet begins to scribble down his daily observations, musings, and recollections in a notebook. He journeys to the Backcountry for restorative interludes and finds motivation in nature, flowers covered in morning dew.

Back in Paris, the artist conducts court in his workshop and encounters Suzon, a mystery muse. Suzon’s cold blue eyes captivate him, and he decides to paint his final masterwork, A Bar at the Folies-Bergere, life-size, and stakes his health to do it. Maureen Gibbon’s sensuous depiction of Manet’s final years, accompanied by his own drawings, is a living monument to the persistence of the artistic soul.

- This stunning historical novel imagines Édouard Manet’s last days

- Manet's daily impressions, reflections, and memories in a notebook

- Features 11 original illustrated sketches

Édouard Manet: Rebel in a Frock Coat (1997) by Beth Archer Brombert

In Brombert’s pages, Manet comes to life. The biography seems at times like a lengthy and detailed 19th-century book. Brombert’s painting of Edouard Manet is not just a portrait of a complicated artist, but also, in its force and breadth, a profile of an era. One of the delights of reading her is watching her weave life, creativity, and history into a seamless tapestry. The art arises from life, and in the wider definition possible: in terms of its creator’s experiences and interests, as well as in terms of its historic environment.

- A biography that reads like a detailed 19th-century novel

- A complex portrait of both an artist and the Impressionist age

- Richly detailed and informative

And that wraps up our look at the life and art of Édouard Manet. The artist Édouard Manet was a French Impressionist known for drawing images of everyday life. Manet grew up in the upper classes yet had a bohemian lifestyle. Manet’s paintings shocked the French Salon audience with his disregard for scholastic norms and strikingly modern representations of city life. Two of his early masterpieces, “Olympia” (1863) and “Le déjeuner sur l’herbe” (1863), aroused passionate upheavals and acted as key points for the emerging artists who would build the French Impressionist movement.

Take a look at our Manet paintings webstory here!

Frequently Asked Questions

When Was Édouard Manet Born?

Édouard Manet was an Impressionist artist from France. Manet the artist was born on the 23rd of January in 1832. He was born in the city of Paris.

What Was Manet Known For?

He is attributed for promoting the alla prima painting method. Rather than layering colors, Manet would instantly lay down the hue that best suited the final impact he desired. The Impressionists popularized the technique, finding it admirably suited to the requirements of capturing effects of light and atmosphere when painting outside. Manet’s modernism stems mostly from his ambition to modernize earlier forms of paintings by introducing new content or modifying traditional components.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Édouard Manet – The Godfather of Modernism.” Art in Context. December 9, 2021. URL: https://artincontext.org/edouard-manet/

Meyer, I. (2021, 9 December). Édouard Manet – The Godfather of Modernism. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/edouard-manet/

Meyer, Isabella. “Édouard Manet – The Godfather of Modernism.” Art in Context, December 9, 2021. https://artincontext.org/edouard-manet/.