Avant-Garde Art – One of the Major Art Movements of the 20th Century

What is Avant-Garde art? The Avant-Garde style refers to Modern art’s capacity for societal, political, and cultural revolution. Avant-Garde artists aspired to defy accepted artistic criteria in order to develop new paradigms of creation. It was one of the art movements of the 20th century with a revolutionary social and political objective, a desire to deconstruct and rebuild social institutions that were viewed as inextricably linked to conventional standards of aesthetics.

Exploring the World of Avant-Garde Art

Even though the concept of the Avant-Garde implies a concern with blazing a trail, in virtually all instances this was motivated by a want to convey a more accurate image of “reality.” Avant-Garde artists have created art that has typically been interpreted in two ways. On the one hand, it is viewed as intimately tied to a progressive political or social agenda, with transgressive artwork serving as a platform for subversive political activities.

Avant-Garde art, on the other hand, has been viewed as the sphere of pure artistic experimentation, unrestrained by any societal concerns.

These two meanings each have their own historical accounts, classifications, and analytical rubrics, which frequently clash with one another. Avant-Garde paintings have typically been connected with a certain movement, ranging from Impressionist to Realistic to Expressionism to Modern art, and so on.

Part of the Avant-Garde artists’ purpose and meaning has always included identifying a precise and systematic set of goals for their work, which is usually connected with a close-knit network of colleagues or comrades who provide the foundation for their creation.

Origins of Avant-Garde Art

Initially, “Avant-Garde” was a French military word for what we would call the spearhead of infantry in English. However, its earliest use in art predates the birth of any particularly Avant-Garde art groups by several decades. The term first appeared in reference to French art only, with Henri de Saint-Simon, a French social thinker, being credited with coining the term.

Saint-Simon, whose political and socialist theories held substantial influence, was an important thinker at the time and believed that the social power of the arts, along with scientists and industrialists, would help artists to emerge as the new rulers of society. After this, “avant-garde” became a term that was frequently used when talking about artists, with many attributing the realistic style of Gustave Courbet’s paintings as a major departure point.

Saint-Simon penned: “We artists will service you as Avant-Garde – the ability of creatives is the most direct and immediate: when we want to propagate concepts among mankind, we emblazon them on stone or canvas. What a glorious destiny awaits the arts: to wield constructive influence over civilization, to perform a genuine spiritual duty, and to advance boldly in the vanguard of all mental facilities!”

Yet, owing to a paucity of literary identification procedures at the time, as well as Saint-Simon’s close working ties with his apprentice Olinde Rodrigues, academic interpretations concerning the real origins of this notion have differed. In any event, it is apparent that, while the concept of Avant-Garde art was later associated with revolutionary aesthetics and procedures, Saint-Simon and his pupils were unconcerned with such issues. Avant-Garde art, according to them, is that which serves the principles and principles of social progress, “exerting a constructive power over society.”

This concept, which emphasized and even required concern for social change, remained a constant influence on Avant-Garde artists and commentators even as their approaches got more specialized.

Precursors of the Avant-Garde Style

The concept of Avant-Garde art arose during a period of social turmoil, and it was initially one of several competing ideas to describe and address it. However, by the early 1800s, Saint-Simonism, which emphasized the role of the economic class and sciences in regenerating society, had become an especially strong influence.

Saint-Simon’s theory was unusual in that it broadened the idea of the middle class to also include scientists, entrepreneurs, bankers, and managers.

This broadening served as a model for the eventual inclusion of creatives of all fields as catalysts for change. Saint-Simon’s theories gained traction until the end of his life, when a number of pupils, including Barthélemy Prosper Enfantin, took them into the mid-nineteenth century. Friedrich Engels and Karl Marx, the founders of Communism, subsequently hailed Saint-Simon as an “idealistic socialist,” claiming his views as an influence for their own.

Saint-Simon also impacted Pierre-Joseph Proudhon’s creation of anarchism.

The French Revolution Influence

The notion of Avant-Garde art took shape in France during the early-to-mid 19th century. These 18 years were marked by political upheaval, social revolutionary movements, and anti-repression forces. Revolts and rebellions broke out across Europe in 1848, from Italy to Scandinavia to Germany and Hungary.

Among its effects were extensive starvation and unemployment, industrialization’s inequity, and the pressures of repressive governance. The 1848 Revolutions were also known as the springtime of the People, emphasizing the group’s inclusive and democratic underpinnings.

Trends and Concepts of Avant-Garde Art

Emerging during the late 1960s and early 1970s, the Avant-Garde style led to the arrival of entirely new forms of contemporary art, which were all Avant-Garde by definition. Moving from Realism to Impressionism, Expressionism, and Cubism, Avant-Garde artists aspired to define a clear set of goals for their artworks which strayed tremendously from traditional values that were previously upheld.

As such, the beginning of Avant-Garde art led to the beginning of contemporary art in society.

As the key notion for comprehending the evolution of art during the 20th century, Avant-Garde art was identical to the notion of the “movement.” According to modern philosopher Alain Badiou, “more or less the entire 20th-century art has claimed title to an Avant-Garde role.”

Occasionally, as with Georges Braque’s Cubism or Delaunay’s Orphism, an Avant-Garde movement consisted of only a few individuals.

Surrealism and Dada, on the other hand, emerged as global movements. Regardless of their scope and significance, Avant-Garde art movements frequently situated themselves in contrast to past orthodoxies, whether they were aesthetic criteria or cultural and social conventions.

Museums and Galleries

The rejection of prior social and artistic orthodoxies was a key feature of Avant-Garde art. As a result, its early success was frequently dependent on a tiny number of critics and gallerists ready to challenge established orthodoxies. As art critic Rosalind McEver points out, “Avant-Garde is both a noun and an adjective.

It refers to groups of artists and writers from the 19th century and early 20th centuries who made and distributed art differently than their peers; artists who self-consciously generated ‘isms,’ were supported by themselves or reviewers in small magazines, and displayed and sold their works in personal galleries or artist-run exhibits.”

The foundation of the Museum of Modern Art, the very first institution dedicated to modern art, cemented Avant-Garde art’s dominance as a worldwide cultural movement in 1929. The creation of the Museum was the culminating proof of Avant-Garde art’s social and commercial triumph.

Barr, who was motivated by Kahnweiler, also created a paradigm that chronicled the progression of Avant-Garde art through time, from Cézanne to Cubism (which was accorded major priority), to abstract art. Barr’s belief in teaching the world about Avant-Garde art “compelled an entire group of people to modern art.” At the very same time, “the capacity of an entity to prescribe and regulate art history is clear.”

Alienation and Avant-Garde Artists

The early 19th Romantic groups were the first to highlight the concept of the lone and autonomous artist, frequently represented as a type of Byronic hero. By the mid-19th century, the image of the creative as an outsider from civilization, shunned and rejected by a dullard, capitalist social structure, was not novel.

By the mid-19th century, this had evolved into a more prominent sensation of societal alienation.

Their sheer status as part of the elite was troublesome for mid-91th-century French authors and painters such as Manet, Flaubert, separating them not only from preexisting artistic and social organizations but also producing strongly felt interior dichotomies.” This sensation of isolation became a prominent feature of Avant-Garde artists.

The Avant-Garde frequently aimed to shock the audience in order to raise the consciousness of the alienation that underpins modern reality.

The Avant-Garde shattered conceptions of normalcy or intentionally cultivated a sense of the eerie (as in Surrealism.) Autonomous and alone, the eccentricities of those within the style became the topic of art and the driving force behind it.

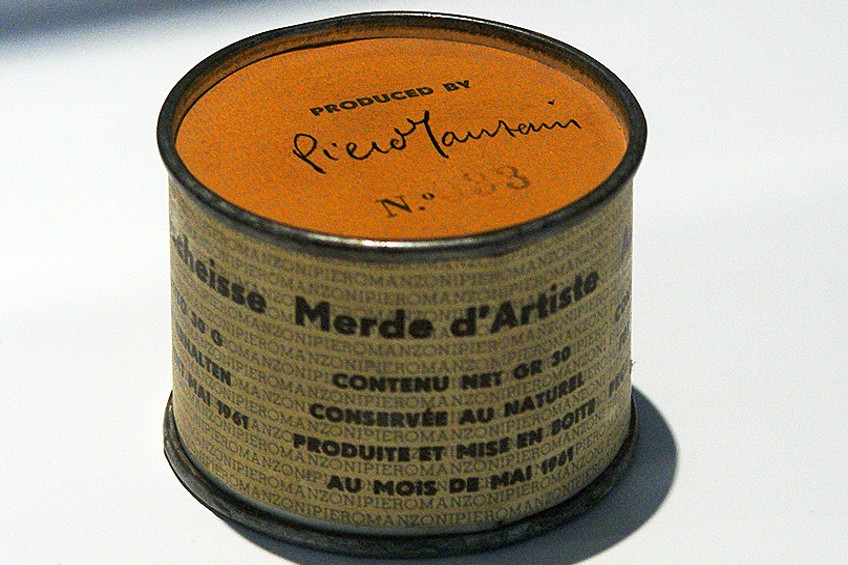

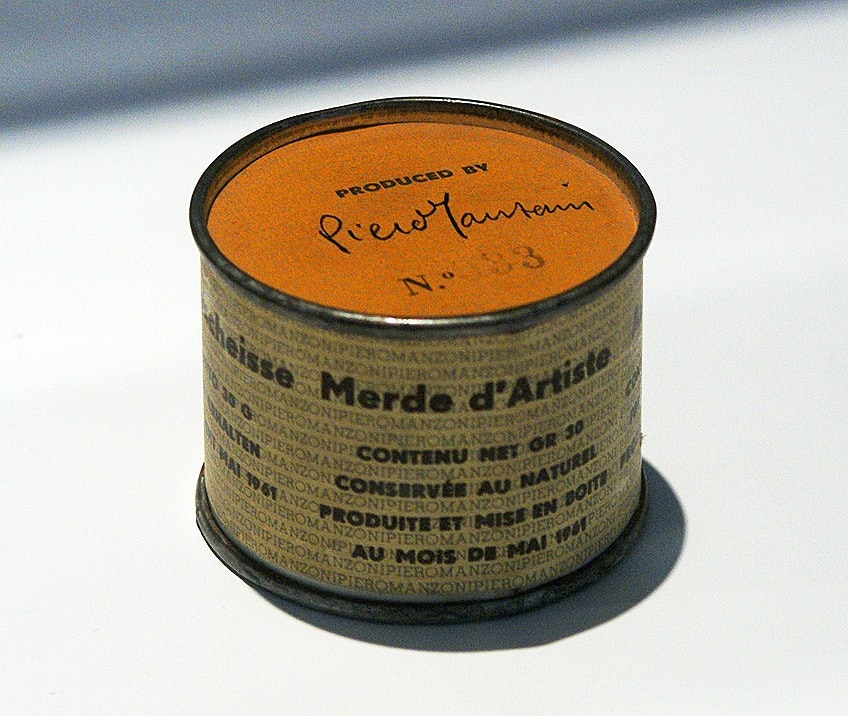

Anti-Art

A contempt for conventional culture’s ideas of aesthetic appeal or quality was a natural consequence of the Avant-Garde artist’s feeling of alienation from its likes and social norms. Some such thought has always underlain Avant-Garde artists’ formulations, from Courbet’s forthright portrayals of working-class life to the Impressionists, who abandoned the arduous arrangement and refining techniques of modern academic artists.

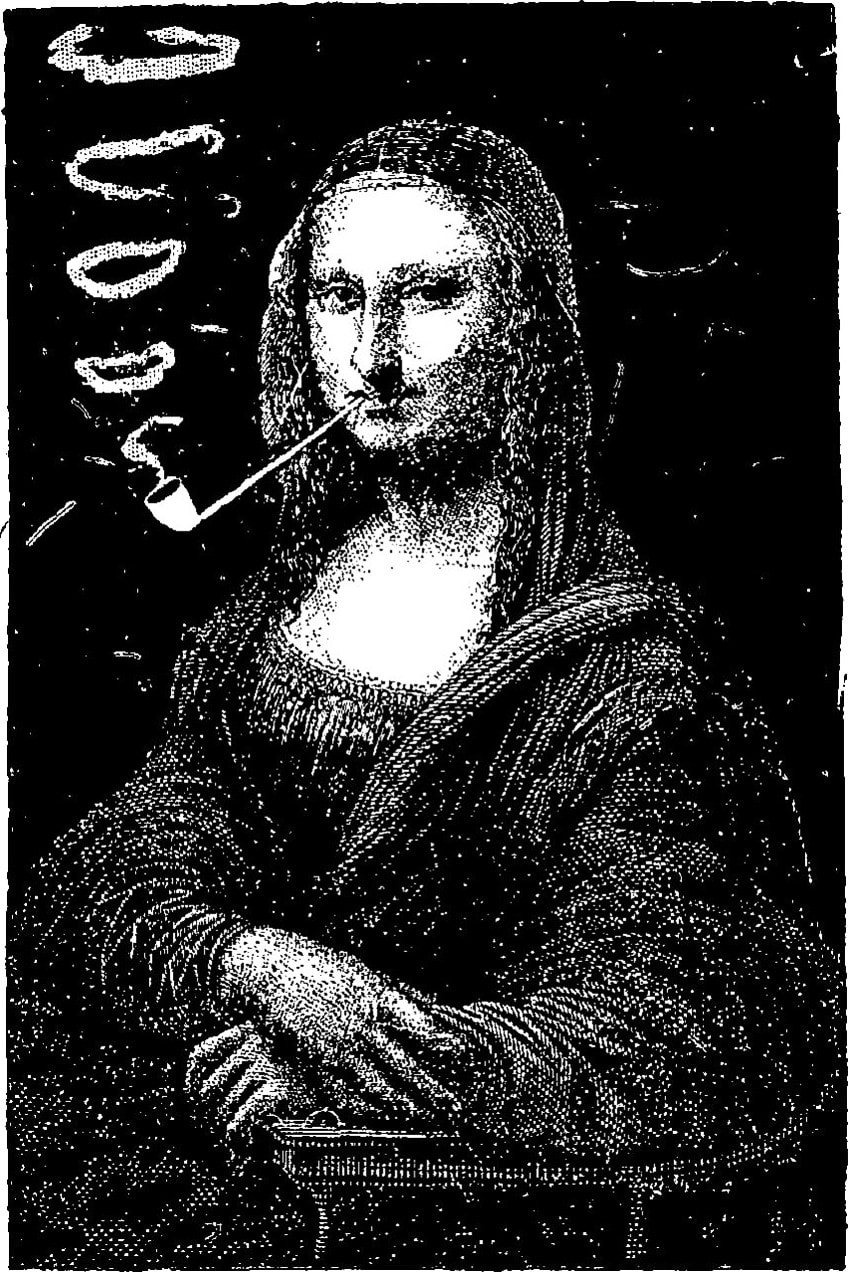

The notion that art does not have to conform to conventional ideas of aesthetic worth perhaps reached its zenith during the 1910s, thanks to the iconoclastic activity of the Dada creatives.

Working in a period of world warfare and upheaval, when all societal standards seemed to be up in the air, artists like Marcel Duchamp began to produce works devoid of any recognizable aesthetic attributes, including, in Duchamp’s case, the notion that they had been made by an artist. His readymades, which were mass-produced, utilitarian objects displayed as sculptures, such as a bike wheel and a toilet, were really unsettling at the time, especially to viewers that were well-versed in Cubism’s advancements.

Virtually all following innovations in Avant-Garde art are based on the premise that art does not have to, or should not have to, adhere to traditional ideas of beauty or aesthetic worth.

Conceptual Art, one of the most influential “neo-Avant-Garde” art movements of the twentieth century, originated with the idea that a work of art may simply be the record of a notion, unattached to any specific item or picture, much alone an aesthetically pleasing one. Other neo-Avant-Garde movements, which emerged after the birth of the Avant-Garde, included Abstract Expressionism, Nouveau Réalisme, Op Art, Pop Art, Kinetic Art, and Minimalism.

Conceptual Avant-Garde Art vs. Formal Versions

The Avant-Garde notion was first grounded by a sense of political or social insurrection. Courbet anticipated the progressive artist to be at odds with society’s dominant powers, and at times he openly, petulantly, and with clear enjoyment confronted the system to a head-on battle. The image of the painter as an outsider from culture, shunned and misinterpreted by an aristocratic society, was not unique by the mid-nineteenth century.

Nevertheless, the connection of Avant-Garde art with social transformation has always been in conflict with certain Avant-Garde artists’ social and financial objectives, for example, the middle-class, materialistic, and nonpolitical Claude Monet.

In their works, the term “Avant-Garde” took on a more purely formal meaning, stressing artistic revolution apart from any political or social goals. Throughout the 20th century, the notion of the Avant-Garde as inevitably socially subversive was increasingly questioned. While Russian Constructivism and Surrealism had major social goals aimed at challenging and changing societal norms, art movements of the 20th century such as Cubism stressed formalism. The rupture with the centuries-old practice of linear perspective by Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso had no overt socio-political motive.

Writer and art critic Clement Greenberg made a name for himself in 1939 when he published his most well-known essay, “Avant-Garde and Kitsch”.

Published in the Partisan Review, Greenberg claimed that true Avant-Garde art was too simple to be used as propaganda or molded towards a specific cause, while the idea of “kitsch” was perfect for inciting fake beliefs. As Clement Greenberg’s theories later became affiliated with the movements of Abstract Expressionism and Cubism, he linked the Avant-Garde with an “art for art’s sake” technique. For him, art did not need to defend its reality on any social grounds or provide any political purpose.

Science and the Avant-Garde Style

Scientific advancements frequently influenced Avant-Garde artists, who combined technological motifs and notions into their creative inventions. Neo-Impressionism, was among the first Avant-Garde artistic groups to openly accept the scientific hypotheses, informed by academic research on illumination by the retina. George Seurat has been characterized as “a technician of his works, dissecting the entire into basic prerequisites presenting the functioning structural parts in the final form, without decoration.”

The prominence of science and technology has also influenced how artists and artworks are seen.

Russian Constructivists considered themselves as “constructor engineers,” as illustrated by El Lissitzky’s self-portrait The Constructor (1924). According to Kuspit, “most pieces of Avant-Garde artwork, in reality, appear to be breakthroughs, and most are machine-made instead of handmade.”

These concepts perhaps reached their height with the mid-twentieth-century Concrete art movement, and the concept of the artwork as removed from the artist’s emotive involvement was also impactful on the creation of Conceptual artworks later in the century.

Avant-Garde Paintings

Although the concept of the Avant-Garde implies a concern with trying something new in practically all circumstances, this was driven by a desire to portray a more accurate image of truth. That implied portraying the tough work-life that had been banned from the academic canvas for Gustave Courbet, while it implied acquiring the light effects on the retina at the instant of awareness for the Impressionists. It also meant portraying the undetectable real scientific powers at work beneath the exterior of observable reality for the Constructivists.

However, the desire to depict reality in a freshly exact manner was the underlying goal in all situations.

The Painter’s Studio (1855) by Gustave Courbet

| Date Completed | 1855 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 361 cm × 598 cm |

| Current Location | Musée d’Orsay, Paris |

This artwork, which depicts the artist reclining with brush and palette in hand, contemplating the scene he has been painting, is meant to be an analogy for the artist’s lifestyle. The piece was titled “a veritable allegory recapping seven years of my artistic and ethical life” by Courbet. A naked model symbolizing a muse and a tiny kid signifying innocence frame the artist, while the space is packed with numerous familiar people. Charles Baudelaire, the famed poet, and critic, is sat on a desk studying in the far corner, among the cultural elite, while different individuals from all parts of society are seated on the left.

The artist stated that he wanted to show “society at its finest, worst, and mediocre.”

As he went on to say, “It’s as if the entire universe is coming to me to be portrayed. On the right, all the stockholders, by which I mean friends, coworkers, and art enthusiasts. The other realm of everyday existence is on the left, with the multitudes, despondency, poverty, money, the abused and the abusers, individuals who earn a livelihood from death.” Courbet, a Realism pioneer, defined the concept by declaring, “Realism is democracy in art.” “He regarded his fate as a continuous vanguard movement against the powers of academicism in artwork and rigidity in society,” writes art critic Linda Nochlin.

Following the refusal of the judges at the 1855 Paris World Fair to show this piece, Courbet launched The Pavilion of Realism, his personal exhibit, where he also exhibited The Burial at Ornans, which had also been denied. Courbet’s show, aided by his sponsor, Alfred Bruyas, who is also seen in The Painter’s Studio, was a resistance to the official locations.

“The extensive social ideologies of the mid 19th century are not provided interpretation in an adequately sophisticated pictographic and stylistic form until around seven years after the 1848 Revolution, in Courbet’s The Painter’s Studio – Courbet’s artwork is ‘Avant-Garde’ if we comprehend the interpretation, in concepts of its etymological inference, as suggesting a union of the communally and creatively progressive,” says Nochlin.

“The Painter’s Studio”, in summary, is a vital presentation of the most liberal political ideals in the most sophisticated formal and iconographic language accessible in the midst of the 19th century.

Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe (1863) by Édouard Manet

| Date Completed | 1863 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 208 cm x 264 cm |

| Current Location | Musée d’Orsay |

Manet’s stunning landscape picture, depicting two fully dressed men eating lunch on the lawn with a naked lady, notoriously caused a stir when it was shown in the Salon des Refusés, an exhibit for paintings denied by the official Paris Salon, in 1863.

Although Manet never completely associated himself with the Avant-Garde requirements of the Impressionist artists, a younger generation of creatives saw him as a role model, and with creations such as “Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe“, he undoubtedly kept breaking down many of the gates that later Avant-Garde creatives would flow through in their pursuit for the unique.

This artwork was Avant-Garde in two ways, opposing both the era’s aesthetic tenets and its capitalist moral and social ideals. In the first instance, the huge size of the canvas contrasted with the artwork’s seemingly banal, contemporary subject matter, the image portrayed on a scale generally reserved for historical and legendary themes.

The piece’s tonal characteristics were also unusual, with the harsh light and shadow contrasting with the seeming outdoor scene (Manet notably never embraced the Impressionists’ excitement for painting en Plein air) and bringing attention to the massed white skin of its primary subject.

And much of the background brushwork appeared haphazard, nearly half-completed , as if the arrangement was attracting notice to itself as such: a mere conceit or fabrication, abandoned before completion. But it was the work’s subject matter that was genuinely stunning. Nude women were allowed in academic art as long as they were depicted in the context of a historical situation, putting the nudity at an intellectual and moral distance.

Manet’s scene depicted a naked person without any of the veil of the historical story, making it more vivid and startling to its viewers. With this attitude, he cleared the way for the Avant-Garde initiatives of the next decades to become increasingly unafraid of nudity and moral disobedience.

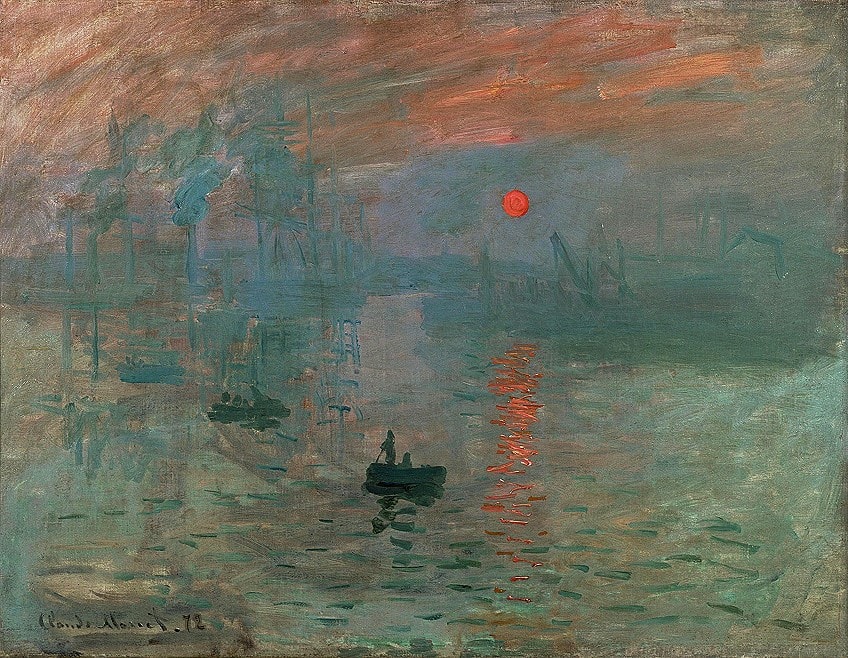

Impression, Sunrise (1872) by Claude Monet

| Date Completed | 1872 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 48 cm x 63 cm |

| Current Location | Musée Marmottan Monet |

The Impressionists, led by Claude Monet, were the first Avant-Garde movement to attain international popularity and reputation. Monet portrays dawn in the harbor city of Le Havre, the family home to which he had returned for a holiday, in this piece, from which the name “Impressionism” was derived indirectly. The essential blue and orange color palette, paired with the rapid, spontaneous brushwork, is intended to portray the visual impression generated by the landscape at a specific point in time, rather than highlighting every detail.

This revolutionary method was not accompanied by radical social beliefs in Monet’s instance, but it put him into a characteristically “Avant-Garde” posture of oppositionality to conventional culture and the art world.

In 1862, Monet encountered a group of young artists in the workshop of painter Charles Gleyre, including Frédéric Bazille, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and Alfred Sisley. These painters, along with Morisot and Pissarro, constituted the foundation of the Impressionist style, which developed its concepts for many years – under the unofficial guidance of the elder artist Édouard Manet – before achieving financial success.

Monet and his colleagues founded their own club to support and show their art after being repeatedly rejected by the Paris Salon. Though we are familiar with Monet and his contemporaries’ approach of capturing the natural world, it was groundbreaking at the time to convey the nuances of a subject in such a swift and instinctive manner, as it was to create on-site as Monet had done to produce Impression, Sunrise.

Impressionism’s formal advancements, as well as its inevitable antagonism to prevailing social and cultural conventions, established the parameters for the evolution of Avant-Garde art over the next century and a half.

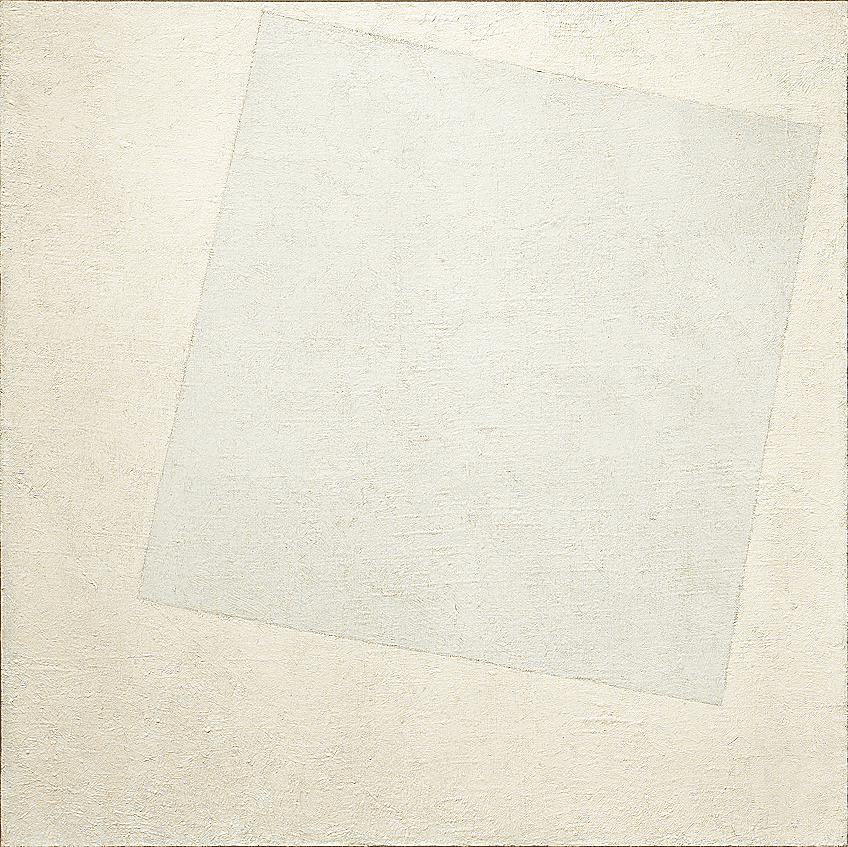

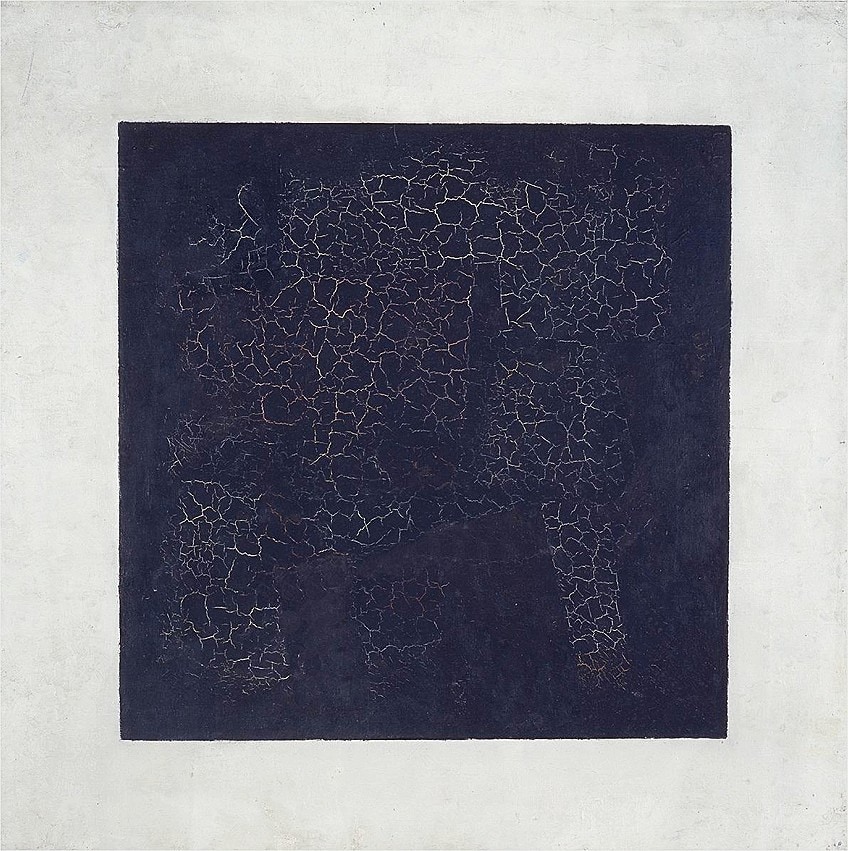

Black Square (1915) by Kazimir Malevich

| Date Completed | 1915 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 200 cm x 222 cm |

| Current Location | Museum of Modern Art |

This well-known piece consists of a black square on a white backdrop. When viewed closely, the piece displays small fissures in the surface caused by aging pigment, as well as brushwork and a fingerprint. Nevertheless, it was the work’s reduction of the image plane to a single, essential geometric shape that distinguished it as both a bold excursion into abstraction and a distinct Avant-Garde event. The picture was shown as if it were a Christian icon during The Last Futurist Exhibition of Paintings in St. Petersburg in 1915, raised and exhibited in the corner of the space as was typical in Russian households.

Malevich referred to the piece as “the initial stage of the pure invention in art,” the “embryo of all potentials.” In his future works, the black square became an implied construction block.

Whereas the Cubists challenged the centuries-old law of the image plane, Malevich regarded Avant-Garde painting as ushering in a new society by liberating itself from the responsibility to depict reality entirely. Malevich pushed for the “freedom of things from the duties of art” in his 1915 article, “From Cubism and Futurism to Suprematism: The New Realism in Painting,” presenting Suprematism – the movement he founded – as an evolution of Cubism that had not gone far enough. “A decorated surface is a live, breathing shape.

The shapes of suprematism, the new artistic realism, already bear witness to the discovery of structures from nowhere by instinctive reason. The cubist endeavor to deform true shape and break up items aimed at creating manufactured creations independent-life.” Malevich’s work was influenced by the Russian Constructivist movement and the atmosphere of revolutionary agitation in the preceding years, the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917.

Malevich’s Black Square was an exceptional example of Avant-Garde inventiveness by reducing the image plane to the bare minimum of formal components and by relating his works to a revolutionary social time.

The debate may appear intellectual, yet time is important to avant-gardism as a quality judge. The military word refers to individuals who are deployed ahead of the regular forces, those who will eventually be followed by the masses. The importance of Avant-Garde art stems in part from the fact that it was created first. Malevich’s Black Square is an excellent example, not least since Malevich himself dated the piece, which is considered to have been created in 1915, reinforcing the significance of being first.

When Malevich reproduced the piece in the 1920s, geometric abstraction had taken root; the aesthetic worth of the subsequent models may be indistinguishable, but their art-historical and, possibly, market values are quite different.

Cut with a Kitchen Knife Dada (1919) by Hannah Höch

| Date Completed | 1919 |

| Medium | Cut Paper Collage |

| Dimensions | 144 cm x 90 cm |

| Current Location | National Gallery, State Museum of Berlin |

Hannah Höch’s pioneering collage employs newspaper and magazine clippings to illustrate the silliness and depravity of current German society. According to Anahid Nersessia, “the collage is a profoundly evocative act of bricolage, a putting together of objects that come to signify the broken aspect of the civilization from which they are collected.”

The piece reveals postwar Berlin’s cultural polarities and divisions. Among the clippings are photographs of artists Käthe Kollwitz and Pola Negri, as well as political intellectuals and leaders such as Karl Marx and Vladimir Lenin.

A little map of Europe in the lower right corner illustrates the nations where women have the right to vote. Höch was noted for her sharply political collages in which she plundered and recombined pictures and text from mass media to criticize popular culture, the failures of the Weimar Republic, and the socially created roles of women. Höch’s pioneering use of photomontage to profoundly question social, cultural, and aesthetic conventions established her as a pivotal character in early Dada and an outstanding Avant-Garde figure in the most socially involved sense of the word.

She displayed this piece, as well as others, at the First International Dada Fair in Berlin in 1920, where her work was praised, despite the fact that her male colleagues had first tried to prevent her from participating.

The practice of photomontage became highly popular and was borrowed by successive groups from Surrealism to Fluxus throughout the 20th century. As Heidi Hirschl Orley points out, “Höch’s daring collisions and permutations of widely circulating image fragments connected her work to the public and reflected the defiant, skeptical attitude of the interwar era, which felt like a new age to many. Through her extreme experiments, she created an essential Avant-Garde aesthetic vocabulary that still resonates today.”

The Three Musicians (1921) by Pablo Picasso

| Date Completed | 1921 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 200 cm x 222 cm |

| Current Location | Museum of Modern Art |

Since the early 1900s, Pablo Picasso, one of the creators of the Cubist movement, has been making Avant-Garde artworks. This artwork from 1921, on the other hand, depicts the radical social context with which the Avant-Garde was frequently connected.

The right-hand Harlequin figure is considered to be Picasso, who frequently depicted himself as the mischievous character of Italian theater, while the center person in white is thought to be Guillaume Apollinaire, a notable Avant-Garde art critic and close friend of Picasso’s.

The person, dressed as Pierrot, plays a musical instrument yet exudes gloomy estrangement. Max Jacobs, the poet, and close friend, is seen on the right dressed as a monk, having joined a Benedictine monastery in St.-Benoît-Sur-Loire. As he and Georges Braque created Cubism, through its incarnations of Analytic and Synthetic Cubism, Picasso rose to prominence as a prominent Avant-Garde artist. As a consequence, one of the most Avant-Garde groups is Cubism.

Figures were broken down into geometric shapes, colors were brighter and reduced, and collage was used to create an inventive outcome that is still influencing art today. If you look at a chronology of art history, you can see that Western visual civilization can be divided into two distinct periods: before and after Cubism.

This picture contains two variants, both of which are viewed as the end and climax of Picasso’s Synthetic Cubism era.

The figurines are painted, yet they look like paper cutouts assembled like jigsaw puzzles from varied wide planes of color and textured paper. Picasso portrayed a collection of works, including these two, while holidaying with his relatives at Fontainebleau, which also highlighted Commedia dell’ Arte imagery and the influence of theatrical design, as he had been operating with the recognized dramatic producer Sergei Diaghilev for the Ballets Russes.

Number 1 (1949) by Jackson Pollock

| Date Completed | 1949 |

| Medium | Enamel and metallic paint on canvas |

| Dimensions | 172 cm x 264 cm |

| Current Location | Museum of Contemporary Art |

This massive picture, with its frantic swirl of rhythmically poured layers and lines of industrial paint, typifies Jackson Pollock’s “drip painting” method, which gave rise in North America in the 1940s to the movement of Action Painting. Placing the canvas on the floor and splattering paint over it with a variety of tools, Pollock attempted to attain a type of unification with the work-in-progress to generate the emotional energy required to finish it: “I feel more at peace on the floor. I feel closer to the painting, more a part of it, since I can go around it, work from all four sides, and physically be in it.”

It displays a magnificent variety of design and accident underneath the apparent homogeneity of its surface composition. Greenberg saw Abstract Expressionism, particularly Pollock’s work, as the apex of Avant-Garde art because it had broken through to independent abstraction, free of any social concerns. Pollock’s work, according to this interpretation, embodies Avant-Garde art in its formal rather than philosophical meaning.

The formal abstraction pioneered by Picasso and the Cubists reached its apex in the 1940s with the advent of Avant-Garde American art, Abstract Expressionism. Pollock’s method represented his belief that “new requirements necessitate new approaches.” Many following Avant-Garde painters – and perhaps many prior ones – followed a similar guideline, but Pollock’s drip painting style was especially reminiscent of the current Japanese Gutai movement.

Shozo Shimamoto and Jiro Yoshihara founded this group, which produced experimental works that clouded the lines between performing, paintings, and art installations. “They all sought to shatter the conventional brush and move more towards action painting and creating in a different way,” said gallerist David De Buck, “so Shimamoto literally tossed containers, glass bottles, cups full with color onto the canvas.”

This, and several other instances, demonstrate Pollock’s importance in determining the direction of the Avant-Garde in the late 20th century.

Imagen da Yagul (1973) by Ana Mendieta

| Date Completed | 1973 |

| Medium | Chromogenic Print |

| Dimensions | 50 cm x 34 cm |

| Current Location | San Francisco Museum of Modern Art |

The artist is naked and wrapped in greenery and white flowers in this color shot as she rests in an indigenous pre-Columbian tomb built by the Zapotec people. The vegetation that obscures her upper torso appears to be alive as if it were rapidly sprouting out of her figure. She fades into obscurity, a symbol of both death and abundance. This piece was part of Mendieta’s series, which included over 200 pieces, many of which had her lying on the ground, imprinting her body, or blending with the environment, such as the flora in this shot.

The series is regarded as a forerunner in various Avant-Garde movements, including Body Art.

Mendieta’s work, according to art historian Laura Roulet, “encapsulates the comprehensive scope of Avant-Garde 1970s movements – performance, conceptual, feminist, and identity art. A large part of Mendieta’s works required navigating and overcoming limits, some of which were imposed by an art industry that still classified work by gender, race, medium, First World vs Third World, and as high or low art.”

Mendieta defined the series in the following way: “I’ve been continuing on a conversation between the environment and the feminine figure (based on my own shape) and I’m overwhelmed by the sensation of being expelled out of the womb (nature). I become connected with the ground through my earth/body sculptures; I become an augmentation of environment, and the environment becomes an outgrowth of my body.” “My art is the way I restore the links that tie me to the cosmos,” she said of her work’s originality, which was linked to both aesthetic and societal change.

That wraps up this look at the world of Avant-Garde Artists and their artworks. Even though the phrase Avant-Garde was initially applied to creative methods to making art in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, it is now used to define all artworks that push the boundaries of innovative thinking, and it is still used to characterize art that is revolutionary or represents the uniqueness of perception. The Avant-Garde concept entrenches the concept that artwork should be assessed largely on the quality and uniqueness of the artist’s vision and concepts.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is Avant-Garde Art?

The Avant-Garde challenges what is considered the norm, mainly in the cultural world. Some view the Avant-Garde as a feature of modernism. Many artists have identified with the Avant-Garde movement and keep doing so, tracking down their roots back to Dadaism. The Avant-Garde also advocates for drastic societal transformations. Saint Simonian invoked this notion by asserting that the power of the arts is actually the most direct and fastest means to a societal, political, and economic revolution.

What Defines the Avant-Garde Art Style?

Despite the fact that the term Avant-Garde was first applied to creative methods of making art in the twentieth century, it is now used to describe all works of art that push the limits of ingenuity, and it is still used to describe art that is innovative or symbolizes the individuality of perspective. The Avant-Garde philosophy holds that art should be judged primarily on the originality and distinctiveness of the creator’s vision and thoughts. Avant-Garde artists attempted to create new paradigms of production by defying conventional artistic standards. It was one of the art movements of the twentieth century with a radical socio-political goal.

Who Were Important Avant-Garde Artists?

Most of the influential artists who were classified as working in the Avant-Garde art style were known for their contributions within distinctive moments. Some of these artists include Marcel Duchamp, who created the infamous Fountain (1917) during the Dada era, Jackson Pollock, who perfected the drip technique during Abstract Expressionism, and Georges Braque, a founder of Cubism, among others.

What Does the Term Avant-Garde Mean?

Originally a French military word that was used to denote the spearhead of infantry in English, the term Avant-Garde first appeared in the art world and was referred to only French Art. French Socialist thinker, Henri de Saint-Simon, is credited with coming up with the name.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Avant-Garde Art – One of the Major Art Movements of the 20th Century.” Art in Context. March 25, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/avant-garde-art/

Meyer, I. (2022, 25 March). Avant-Garde Art – One of the Major Art Movements of the 20th Century. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/avant-garde-art/

Meyer, Isabella. “Avant-Garde Art – One of the Major Art Movements of the 20th Century.” Art in Context, March 25, 2022. https://artincontext.org/avant-garde-art/.