Conceptual Art – An Exploration of the Conceptualist Art Movement

Emerging as an art form during the 1960s, Conceptual Art investigated the foundations surrounding the concept of what was considered art. From the mid-1960s to the mid-1970s, the Conceptual Art that was created embodied the themes of irony, seriousness, as well as shock in order to be viewed as both something and nothing. In doing so, artworks no longer subscribed to the traditional values and aesthetics that underpinned conventional art. The Conceptualist Art movement was more interested in understanding the strategies and ideas that went into creating art as opposed to the artwork itself.

Conceptual Art: An Introduction

Known as one of the most radical and controversial movements within modern and contemporary art, Conceptual Art revolved around the idea that the concepts involved within the production of an artwork took precedence over the actual work. Emerging in America during the 1960s, the term Conceptual Art typically refers to art that was made during the mid-1960s and 1970s, with this period paving the way for other unconventional movements to emerge following its peak.

Also known as Conceptualism, this movement combined various tendencies of artistic creation rather than existing as one straightforward and coherent movement.

Conceptualism took on countless forms and was present in works like art pieces, performances, happenings, and fleeting moments. Works created within this movement began to question the idea of art itself, as the previously dominating Modernist movement and its prioritization of the aesthetic beauty within art was rejected.

Despite originating in America, Conceptual Art also reached Latin America, Europe, and the Soviet Union. Within Latin America, artists preferred a more straightforward political response within their artworks. In Europe, Conceptualism was also widely investigated and developed as the countries were very political at that time. Finally, in the Soviet Union, Russian artists mixed their own Soviet Socialist Realism with Western Conceptualism and American Pop in order to create a movement where artists were deemed as Moscow Conceptualists.

The Conceptual Art definition was based on the notion that the essence of art was made up of a work’s ideas and concepts, as its primary claim was that an artistic idea could exist as the work of art itself. Several artists and art historians disregarded the movement completely and refused to classify any work created within this period as art. This was because conceptual artists classified expression, skill, aesthetics, and marketability, which were usually standards upon which artwork was evaluated, as essentially irrelevant.

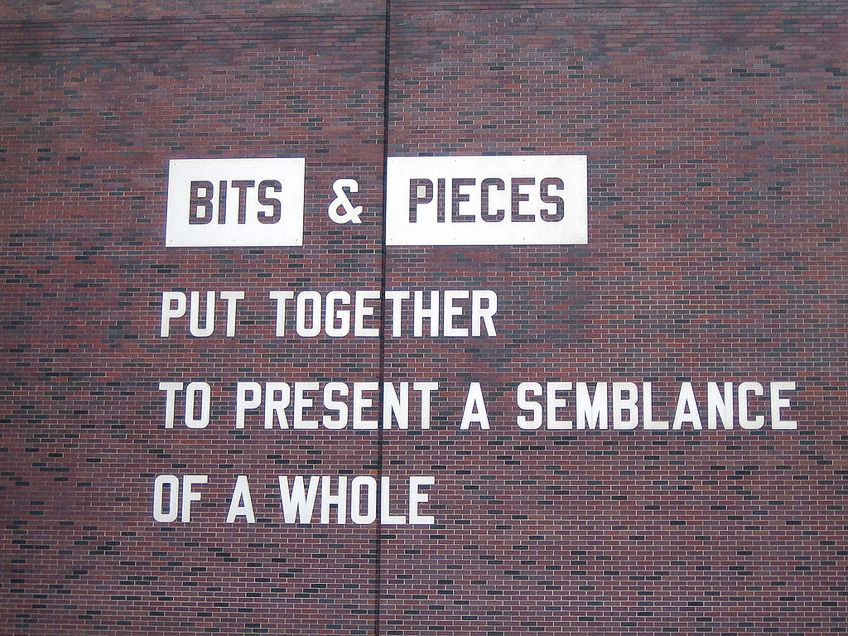

Conceptual artists used whatever materials and forms were available and appropriate to them in the moments they needed them so as to effectively get their ideas and concepts across. The result of this were artworks that took on a variety of forms, such as performance pieces, writings, as well as the use of everyday objects. Artists investigated the notions of art-as-idea and art-as-knowledge through incorporating concepts of linguistics, mathematics, and process-oriented thoughts within their works.

Existing as a movement that favored ideas over formal and visual elements, conceptualism as a whole was thought to be even more simplified than works such as Andy Warhol’s Brillo Boxes (1964), which consisted of a silkscreen copy of commercial packaging. Thus, Conceptual Art was thought to heavily contradict what had previously stood for art.

Conceptual artists acknowledged that all art is fundamentally conceptual. In order to highlight this understanding, many conceptual artists decreased the material presence of their works as much as possible, to the point where artworks were viewed as essentially dematerialized.

The success of conceptualism art was built upon the foundations of previous avant-garde art movements such as the Cubist, Dada, Abstract Expressionism, and Pop movements. A true Conceptualist artist classified themselves at the extreme end of this progressive and experimental scale, as they were able to deliberately expand the boundaries of art without any concern for what was previously considered as traditional art.

Heavily influenced by the harsh simplicity of the Minimalist movement, Conceptualism rejected the previous conventions of sculpture and paintings that were seen as the fundamental building blocks within artistic creation.

At its core, art produced by conceptual artists did not need to resemble traditional artwork, as it did not need to take on a physical form at all.

The allure of Conceptual Art, which encouraged many artists to partake within the movement, was the idea that if an artist began an artwork, the gallery or the audience will in some way finish it for them. This was known as institutional critique, which demonstrated an even bigger shift away from object-based artwork as it deliberately expressed the importance that society placed on cultural values as a whole.

During the 1960s, prominent New York art critic Clement Greenberg stated that Modern art had reached a peak in its process of reducing and refining the formal nature of artistic mediums. However, by the end of the 1960s, it became clear that Greenberg’s ideas surrounding the strict boundaries of each medium were no longer deemed correct by artists who wished to experiment. Thus, this newfound view surrounding the possible limitations of mediums allowed Conceptualism to emerge successfully.

Conceptualism responded to the commodification of art by attempting to subvert galleries as the location and determining factor of art as well as art markets as the owners and distributors of art. Influential artists such as Lawrence Weiner stated that once their artworks were viewed, they essentially belonged to the minds of the audiences.

This idea emphasized the core tenet of Conceptualism, which was that the idea was more important than the actual artwork.

Overall, the majority of Conceptual Art that was created was self-reflexive in nature, as it exposed the insecure and self-conscious aspects of artists that were previously hidden. Thus, by using minimal materials and linguistics, a truly Conceptualist artist was able to push the boundaries and create art that was purely about art.

Defining the Conceptualist Art Movement

The term “concept art” was coined by the artist and philosopher Henry Flynt in 1961, when he described his performance pieces as concept artworks, but it was not until the late 1960s that Conceptual Art was seen as a definable movement. Flynt intended the term to refer to artworks that were a critique of logic or mathematical insight, but it was not truly applicable until artist Joseph Kosuth properly redefined it to fit within the Conceptualism art movement.

Building on the ideas of Kosuth, American artist Sol LeWitt further defined the terms of conceptual art within his influential 1967 article titled “Paragraphs on Conceptual Art.” His article was one of the most significant writings on Conceptualism, with his definition being one of the first to occur in print.

LeWitt’s writing presented Conceptual Art as one of the latest innovative movements to emerge, as it labeled artworks as both intuitive yet purposeless at the same time.

He stated that the concept exists as the most important aspect within an artwork, with all of the planning and decision-making happening beforehand. This essentially makes the physical completion of an artwork a perfunctory matter, as the importance lies in the idea of the work.

The Forerunners of Conceptual Art

The origin of Conceptualism dates back to 1917, with French artist Marcel Duchamp believed to be the predecessor of the movement. Duchamp led the way for the conceptual artist, as he presented them with examples of original works that were conceptual in nature. His most iconic work, Fountain (1917), demonstrated his favored use of ready-made objects, as he presented a urinal basin that was signed with a pseudonym as a sculpture for inclusion at the yearly exhibition of the Society of Independent Artists in New York.

His work was later rejected, as the jury refused to accept his vulgar piece as art, which displayed Duchamp’s questioning of where the limits and confines of art essentially lay. His critique of what constituted art upset the very traditional definition of art, as he abandoned beauty, rarity, and skill within his works in favor of the ready-mades.

The artistic community did not consider ordinary objects such as Duchamp’s urinal to be seen as art, as they were not made with the intent of being an artwork, nor were they special or handmade. Duchamp’s revolutionary work with insignificant, commonplace objects sparked outrage in the artistic world, which would later lead to the development of Conceptualism as a full-blown art movement. The relevance and theoretical underpinnings within his works were later recognized by Kosuth when he properly defined the movement.

Throughout the Conceptual Art movement, the matching of experimental art that was created in relation to what one’s personal views of what art was about continued to be unimportant. As time went on, Conceptual artists managed to effectively redefine the concept of art to the point where their efforts became widely accepted as art that was worthy of viewing amongst other traditional works.

Conceptual Art Characteristics and Influences

Within the Conceptual Art movement, artists believed that their art was essentially created by the viewer, meaning that the artist and the artwork itself remained irrelevant. Given that the ideas and concepts surrounding an artwork were the central and most important elements, the aesthetic appeal and materials used within the work adopted a secondary role within Conceptual Art.

To emphasize the ideas and concepts about an artwork, artists lowered the material presence within their work to an absolute minimum, which was known as dematerialization. This existed as one of the central characteristics of Conceptual Art, as less emphasis and importance was placed on the materials making up an artwork.

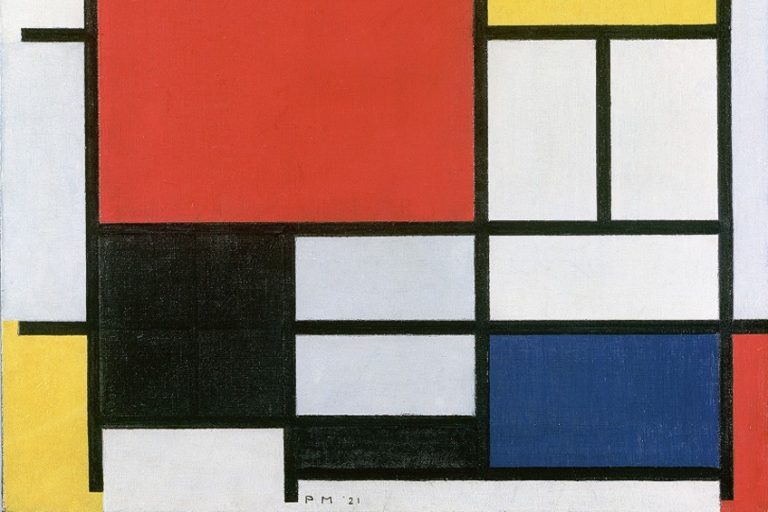

Within Conceptualism, the movement rejected the principles of Formalism, as artists did not see the significance in emphasizing trivial formal qualities such as shape, line, and color. A truly Conceptual artist believed that ideas surrounding the representational and social aspects of artwork were more interesting to consider than the formal elements used to create a work.

Artists involved with the Conceptual Art movement sought to escape the commercialized world of art by emphasizing that the thought processes and methods of production were the facets within which the true worth of an artwork lay. The art forms that they used were deliberately chosen so that they never produced a finished work that could be presented to traditional artistic society as a new form of art. In doing so, artworks were not easily bought and sold, as they did not need to be viewed by audiences in an official gallery setting.

In addition to questioning the structures of the art world, a characteristic that many Conceptual artists inserted was their exploration of ideas surrounding strong socio-political themes within the majority of the work they produced, which in turn reflected their disapproval with society and governmental policies more comprehensively.

Contemporary Influence

Drawing heavily on the influence of Marcel Duchamp and his revolutionary works, Conceptualism challenged the boundaries surrounding what could be seen as art or not, as it gave the artist the power to decide for themselves if their piece of work could be called an artwork. In doing so, Conceptualists put forward the idea that an artwork could fundamentally consist of far-fetched and complex objects and still be deemed art, thus creating a distance between the task of the artist from the physical production of the work.

A characteristic way through which Conceptual Art explored the bounds of artwork was by questioning where the realm of art ended and where utility began. Inspired by the work of Duchamp, artists continued to overturn traditional concepts which had long defined art, as they challenged the ideals of what an art object should be made of and how it should look.

Artworks were viewed as a process instead of a material object and became something that could not be seen or understood simply by seeing, touching, or hearing it. Therefore, a key characteristic within the art production process was the idea of activity, as the process of art-making joined with the final artwork itself to become a truly conceptual activity.

The products of artistic activities were influenced by events such as the Vietnam War and the development of feminism, which led to a reconciliation between the production of art and its artistic and social critiques. Questions about artistic creations were raised, as the very objective of art was questioned. These queries existed as a key characteristic that was ever-present within Conceptual Art.

Ideas like the anti-commodification of art existed as a significant characteristic, as the social and political ideas of art were deconstructed and critiqued within the work of Conceptual artists. Concepts existing as the primary medium was perhaps the biggest characteristic with which to identify art made within this movement, as it took the form of performance art, installation art, and digital art.

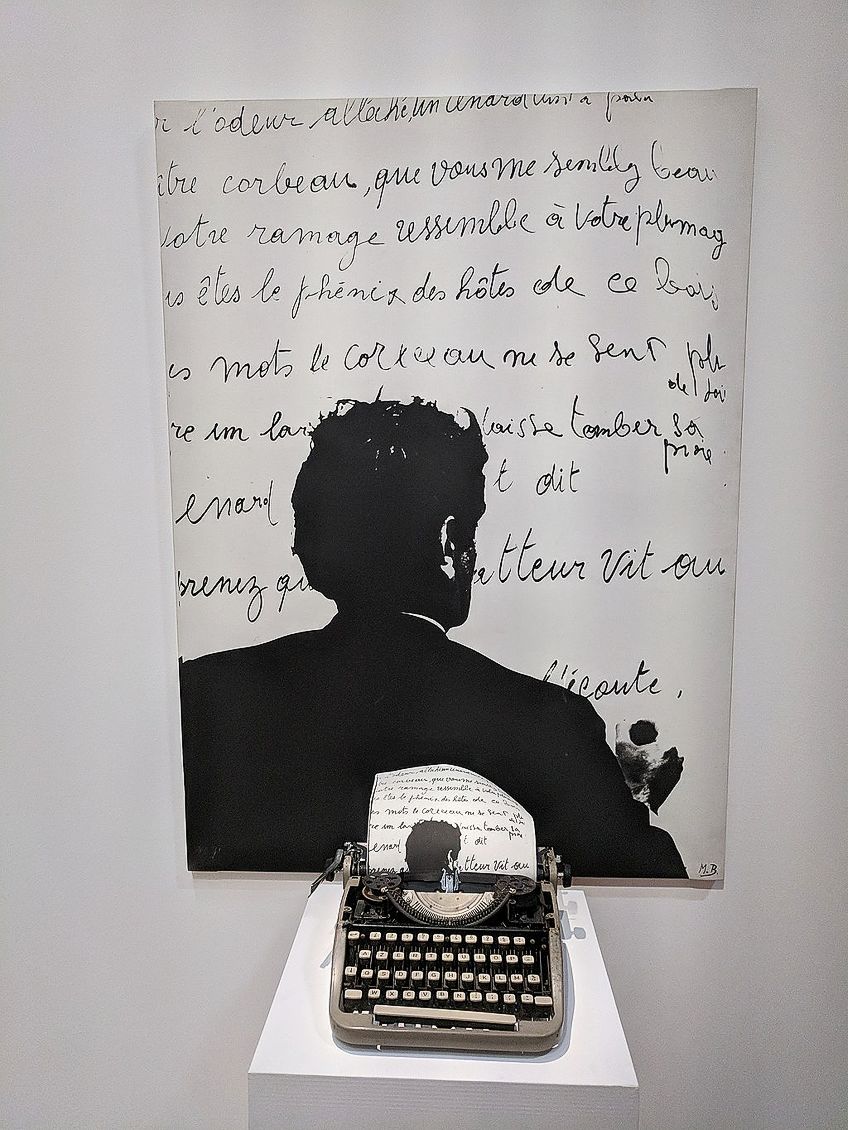

Language as Art

An important distinction between Conceptual Art and traditional forms of art was the use of different artistic mediums. Language was a central concern during the first wave of Conceptualism during the 1960s and early 1970s and was adopted as an exclusive medium by plenty of artists, including Lawrence Weiner, Robert Barry, Edward Ruscha, Joseph Kosuth, and the Art and Language collaboration group.

Despite the usage of text within artworks existing as an established method, Conceptual artists began to create artworks using linguistic techniques exclusively. Previously, language was simply presented as one type of visual element alongside a host of others, as it was viewed as secondary to the importance of the overall composition. However, within Conceptualism, artists discarded this view of language and used it in favor of brushes and canvases within a work, which allowed language to imply its importance.

Language was used by artists in a variety of ways. Lawrence Weiner employed language within his works to help emphasize the thematic content of his works, while artist John Baldessari presented realistic images that he authorized and instructed professional sign-writers to paint.

Within Conceptualism, the return to language-based art was thought to arise from the interest stemming from linguistic ideas of meaning in Anglo-American analytic philosophy and the structuralist and post-structuralist Continental philosophies during the middle of the twentieth century. This shift to linguistics was thought to strengthen and validate the direction that a Conceptual artist took when employing the element of language within their works.

Additionally, early Conceptualists were the first generation of artists who completed a university-based degree in art training. The subsequent education levels of artists were thought to act as a heavy influence towards the inclusion of linguistics within artworks and to stand in place of actual artworks at certain times.

Through adopting language as their exclusive and central medium, Conceptual artists were able to dismiss the remaining authoritative presence that was felt in works towards traditional elements that should be used. Language was able to be applied and experimented with in a variety of ways until it truly became its own form of art as the movement progressed.

Extremist Positions Within Art

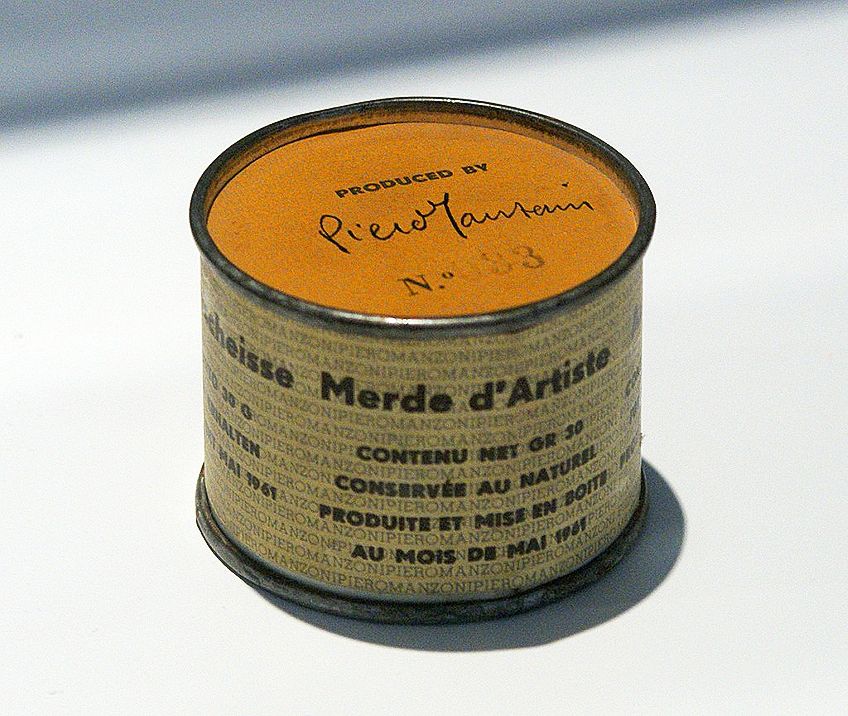

Another characteristic that was present within Conceptual Art was the radicalism that was displayed within artworks. One of the most well-known and extreme examples of Conceptualism was created by artist Piero Manzoni in 1961, where he presented an artwork titled Merda d’Artista (Artist’s Shit). This artwork consisted of 90 tin cans, with the label on each stating that the cans were each filled with 30 grams of excrement. This left most viewers baffled and referred to the provocation that Manzoni attempted to attain within his work.

After the creation of this work, very few Conceptual works were able to combine concept and provocation together in such an extreme way that it became as effective as Manzoni’s work.

Inspired by the seemingly effortless way that Manzoni combined high art with excrement, many artists continued to experiment with this idea of incitement throughout the Conceptual Art movement. Thus, the concepts of provocation and rebellion became a key characteristic within the works that were made.

Notable Conceptual Artists and Their Artworks

Throughout the Conceptual Art movement, many artists produced works of notable importance. A few significant artists have been included here, along with some of their most iconic works within the Conceptual Art movement, as these works accurately demonstrate the core tenets and characteristics that were employed.

Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968)

Known as the forefather of Conceptualism, Marcel Duchamp was creating works that were essentially conceptual in nature years before the movement even took off. One of his most iconic works, which is said to be cited as the first official Conceptual artwork, is his Fountain sculpture created in 1917.

Duchamp infamously bought a standard urinal from a plumber’s shop, signed it with the pseudonym “R. Mutt”, before submitting it as a completed artwork for the open sculpture exhibition of the Society of Independent Artists in New York. Despite being part of the selection committee, Duchamp’s artwork was rejected by the jury as they thought it to be unscrupulous and refused to acknowledge it as art.

This revolutionary artwork was the first of its kind to outwardly reject aesthetic beauty and expertise, as he created a sculpture out of a common, everyday object and demanded it to be regarded as high art. Duchamp’s Fountain demonstrated a developing curiosity of where the boundaries and limitations of formal art lay, as his critique of traditional art began paving the way for the eventual development of Conceptualism.

Robert Rauschenberg (1925-2008)

Another influential artist within the Conceptual Art movement was Robert Rauschenberg. His most notable work was his Erased de Kooning Drawing, which he created in 1953. Rauschenberg erased an artwork that he acquired from the American artist Willem de Kooning, with his finished artwork featuring an almost blank piece of paper framed in a simple gold frame.

Rauschenberg created a number of works that explored the limits surrounding the definition of art, with his artworks drawing great inspiration from Marcel Duchamp. Within his Erased de Kooning Drawing, Rauschenberg intended to discover whether an artwork could be created out of erasure, with the removal of marks being seen as the artwork itself.

Initially, Rauschenberg started out by erasing his own drawings but thought that through erasing his own works, he simply created negated drawings that still belonged to him. He later believed that in order for his idea to become a work of art in its own right, the original work had to belong to someone else. He then approached de Kooning, an artist who he held in high regard, with his idea and asked for a drawing which he could erase.

At first, de Kooning appeared hesitant but understood the concept that Rauschenberg was exploring, eventually handing over a drawing. When choosing an artwork, de Kooning selected one that he would miss and that would be difficult to erase completely, as he believed an added level of difficulty would make the erasure more profound when completed.

The process proved to be labor-intensive, as it took Rauschenberg more than a month and about fifteen erasers to complete the artwork. Artist Jasper Johns went on to inscribe a written caption to the work which read: “Erased de Kooning Drawing, Robert Rauschenberg, 1953.” The inscription, despite its simplicity, existed as a fundamental element within this artwork as, without it, the blank piece of paper inside a frame would be indecipherable.

When asked about his work, Rauschenberg said that his erasure indicated an ending of Abstract Expressionist art and the idea that art had to be expressive. His erasure was the celebration of his idea of an absent drawing, as it existed in place of traditional elements as well as language.

Thus, his work was considered truly Conceptual through its creation. In 2010, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art used various digital capturing and processing technologies to strengthen some of the leftover traces of the original de Kooning drawing. This was done to better understand what Rauschenberg erased and why he chose to do so with an artist he supposedly idolized. However, as de Kooning used erasure frequently within his own drawings, some of the traces that were found were actually erased by him before the work passed into Rauschenberg’s hands.

The resulting image revealed de Kooning’s work in progress, as well as the influence that Rauschenberg had on the artwork when he started his erasure. The power of Erased de Kooning Drawing is derived from the appeal of the unseen as well as the puzzling decision that Rauschenberg made to erase a de Kooning artwork. As we may never know the answer, Rauschenberg’s mysterious work is left open to numerous interpretations.

Sol LeWitt (1928-2007)

Writing one of the first definitions of Conceptual Art to appear in print, American artist Sol LeWitt stated that the idea or concept of an artwork becomes the physical machine that essentially produces the work. LeWitt is possibly best known for his large-scale Conceptual painting artworks which he titled Wall Drawings, which incorporated meticulously arranged colors, designs, shapes, and grids.

These arrangements were drawn in either pencil or paint according to the strict instructions and diagrams that LeWitt produced in order to execute the work correctly. Thus, LeWitt demonstrated that an artist can follow a guideline of methodical points to produce work that is considered as art, as works do not always need to originate from a deeper meaning. Through this process within his artworks, LeWitt shows that his strict ideas behind creating his Wall Drawings are the artworks themselves.

Throughout his career, LeWitt created over 1200 of these drawings, with these works confirming the strong visual vocabulary that he was building. His works displayed modifications on geometric shapes and his drawings eventually developed into structural constructions that were made from materials such as steel, polyurethane, concrete, and stacking cubes.

One of LeWitt’s most well-known wall drawings, titled Wall Drawing #16, was one of the first that he created in 1969. This work consisted of a network of pencil-drawn lines that were governed by an internal logic that was enforced by LeWitt. The gray lines were drawn 12 inches wide and are shown to intersect horizontally, vertically, and diagonally to the right. However, what makes this work so interesting was that it was the first artwork of LeWitt’s that he did not construct himself.

Early in his career, LeWitt reached out to others to help create his many Conceptual painting pieces and wall drawings. Wall Drawing #16 was completed by James Walker. LeWitt would leave detailed instructions and diagrams for his assistants to follow, who would produce the drawings based on their personal interpretations of his instructions. In allowing others to complete his work, LeWitt addressed the time-consuming nature of his drawings.

Most importantly, through choosing others to produce his works, LeWitt demonstrated that the conception of the idea, rather than the physical completion of it, was enough to establish the work as an art piece.

Additionally, LeWitt rejected the traditional importance of an artist’s own hand needing to complete an artwork, as he effectively decentralized himself from the realization of his work, yet was still able to take ownership of the finished piece.

Robert Barry (1936-Present)

Another influential artist within the Conceptualism movement is Robert Barry, who adopted language as the primary medium within his artworks. One of his most well-known Conceptual artworks was his All the Things I Know But of Which I Am Not at the Moment Thinking, created in 1969.

Barry created artworks that probed the concept of absence as well as what audiences perceived to the concept of absence to be, with this artwork speaking directly to his central idea. Displayed as a pencil-drawn wall piece, this artwork merely supplied a simple statement that confused audiences who viewed the work. Additionally, Barry gave no further explanation, meaning that audiences had only his intention to rely on when trying to understand the work.

As displayed within Barry’s iconic artwork, the concepts of meaning and vagueness conflict with one another. When producing this piece, Barry claimed the ideas he was not thinking about as his central idea for this artwork, demonstrating that its physical form was not important. Instead, Barry negotiated the weight of the statement and asserted his use of language to become the artwork itself.

What is interesting to note is that the statement could be spoken, thought, and written differently, yet it is still his artwork no matter the form.

Lawrence Weiner (1942-Present)

Throughout all of the artists mentioned, Lawrence Weiner was one of the most important artists who helped launch the Conceptual Art movement and propel it forward during the 1960s. Known as a linguistic artist, Weiner’s most well-known works have made use of language as his primary medium.

Out of his artworks, his most well-known is his Declaration of Intent, created in 1968. This artwork documented his introduction into the Conceptual Art movement, as the work consisted of three simple terms which he believed to describe and dictate the art-making process. Using language to explain the creation of art, Weiner demonstrates that the emphasis of the work lies within its instructions.

Within the statement, Weiner suggested that an artwork could exist solely in the form of language and thus maintain its conceptual nature, or it could be physically constructed if need be. Weiner’s Declaration of Intent acted as a guide with which to understand the rest of his artworks and the Conceptual movement at large, as the statements demonstrated his thinking about how art was made and received by others.

Joseph Kosuth (1945-Present)

Existing as one of the pioneers of Conceptualism, Joseph Kosuth effectively defined the term “concept art” to appropriately fit into the Conceptual Art movement in his 1969 essay titled “Art after Philosophy.” Within his writing, Kosuth acknowledged the significance and theoretical importance of Duchamp’s work, as he stated that all art created after Duchamp was conceptual in nature, as art could only exist conceptually. Kosuth stated that an art object existed as a mere expression of the idea of art, and after Duchamp’s works, he argued that art’s only duty was to then interrogate and define what art essentially was.

Kosuth encouraged a deep contemplation and questioning of what defined traditional art, with this theme being present within the works he created.

His most well-known artwork, titled One and Three Chairs, was created in 1965 and considers the different codes for a single chair. Within the artwork, an actual chair is situated between a scale image of a chair and a printout dictionary definition of the word “chair.” In doing this, Kosuth presented both a visual and a verbal code of a chair, as he used language to define his artwork to the point where it could be accessible to and understood by any viewer, irrespective of their art knowledge.

Through supplying a real chair with his artwork, Kosuth also gave a code in the language of objects, which defined a chair as an actual wooden object. Kosuth successfully combined a photograph, an object, and an idea to create an artwork that was conceptual in nature, as it forced audiences to question what constituted the “chair.”

The central idea in Kosuth’s work is that audiences are asked which concept made up the real chair. The physical chair could be viewed as a reproduction of the definition, with the photograph being seen as a reproduction of the actual chair. Thus, audiences were left wondering if a combination of all three elements were integral in defining what a chair was, or if the emphasis of a chair was intended to rest on one element entirely.

One and Three Chairs rejected a hierarchical difference between an object and a representation of it, as it implied that a Conceptual artwork could consist of either a physical object or a depiction of it in several forms. Kosuth’s works were conceptual in their creation as he based them on his innate inquiry into the nature of art, which considered all of the implications and aspects that were involved within the creation of an artwork.

The Legacy of Conceptual Art

Despite the movement’s intense introspection, Conceptual Art tackled important issues such as time, space, identity, and authorship within art. Ownership was perhaps the most important topic considered by Conceptual artists, as they raised questions about how concepts surrounding art could be bought and belong to those viewing the work.

The themes that were explored within Conceptual Art were clearly expressed in the real world, as they existed as concepts that truly had no correct answer. When considering artists like Sol LeWitt and the work he produced, viewers were left to ponder the question: What is Conceptual Art?

LeWitt answered this by demonstrating that art did not need to be physically created by the artist to be seen in the same light as traditional artworks, as the ownership of art had changed completely. As the movement progressed, it found its way into various other art movements such as feminist art and performance art. Thus, it is difficult to pinpoint when Conceptual Art truly ended, as other movements continue to borrow some of the core tenets associated with Conceptualism today.

Defining Conceptual Art is a difficult process, as so many variations exist. Due to its inclination to view all art as essentially conceptual, the Conceptualist Art movement is often described to include practices and ideas that were not originally related to Conceptualism. Thus, the line between Conceptual Art and other art movements is vague. Despite the art movement arising in the 1960s, many artists continue to utilize Conceptual Art today.

Further Reading

Conceptualism is a captivating movement to learn about, as different artists introduced different understandings and definitions for the movement. If you enjoyed reading about Conceptual Art and its most influential artists, we have suggested a book that goes into much more detail to further inform you.

Conceptual Art (Movements in Modern Art)

If you are interested in learning more about Conceptual Art, Paul Wood’s book is essential for this. While academic in tone, this book is written for those who want to read in-depth about the movement and understand how and why contemporary art exhibitions began to include everything from rubbish to urinals in their display. The book is coherently written, with some complex jargon appearing at times, and provides a comprehensive introduction to the important figures of the Conceptual Art movement

- Learn everything about Conceptual Art

- What was it? When was it? (Is it still around or is it 'history'?)

- Where was it? Who made it?

Summary of the Conceptual Art Movement

What Is Conceptual Art?

Conceptual Art described artworks that rejected traditional artistic elements such as aesthetic ideals, technical construction, and materials used in favor of the idea behind the artwork.

What Is an Appropriate Conceptual Art Definition?

Also referred to as Conceptualism, this art movement can be defined as one that prioritized the concepts and ideas involved in constructing the artwork over the physical artwork itself. Thus, after understanding the concept, the completion of an artwork is seen as perfunctory.

What Are the Characteristics of Conceptual Art?

Conceptual Art is characterized by the use of a variety of mediums, as well as an incorporation of ordinary, everyday objects. These are known as ready-mades, which Conceptual artists believed to be artworks within their own right. Conceptual Art often has no financial value as it is instead often used to deliver a powerful message.

Who Is the Forefather of Conceptual Art?

Marcel Duchamp is considered the forefather of Conceptual Art, with his ready-mades possessing the characteristics of Conceptualism before the movement even developed. His most well-known work that was created in 1917 remains Fountain, as he labeled an ordinary urinal as art and tried to exhibit it. Fountain is thought to be the first conceptual artwork in history.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Conceptual Art – An Exploration of the Conceptualist Art Movement.” Art in Context. March 23, 2021. URL: https://artincontext.org/conceptual-art/

Meyer, I. (2021, 23 March). Conceptual Art – An Exploration of the Conceptualist Art Movement. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/conceptual-art/

Meyer, Isabella. “Conceptual Art – An Exploration of the Conceptualist Art Movement.” Art in Context, March 23, 2021. https://artincontext.org/conceptual-art/.

Thank you for making Conceptual Art easy to understand. It is really daunting when faced with an academic article and then having to sift through the complicated language in order to complete an assignment. The whole article was very useful for me. Tereza