Academic Art – A Look at the Canvas of Intellectual Expression

What is Academic art? Also known as Academicism, the Academic art style was a true-to-life style promoted by European art academies in the 19th century. The French Académie des Beaux-Arts’ standards greatly impacted this period due to its combination of Romanticism and Neoclassicism elements, with Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres playing a pivotal role in Academic painting. Let us learn more about Academic art below, as we look at the history of Academicism and explore Academic art examples.

What Is Academic Art?

Academicism, which subsequently grew to be associated with Neoclassical painting and the Symbolism movement, expressed itself in a number of sculptural and painterly standards that all artists were expected to adhere to. Subsequent artists who sought to continue this combination of styles included Thomas Couture, William-Adolphe Bouguereau, Hans Makart, and many others.

While the production of Academic artworks continued into the 20th century, the Academic art style had grown devoid of substance and it was fiercely criticized by the artists of a number of emerging movements, one of which was the Impressionism movement.

The History of the Art Academies

Starting in the 16th century, a number of specialized art schools sprung up around Europe, initially emerging in Italy. These schools were founded by a patron of the arts and sought to teach young artists the traditional concepts of art from the Renaissance period. Cosimo I de’ Medici established the first academic of art in Florence in 1563, with the help of Giorgio Vasari, the architect who named it the Academy and Company for the Arts of Drawing.

While it functioned as a type of corporation that any professional artist in Tuscany was able to join, the academy consisted of only the most prominent creative individuals from Cosimo’s court and was responsible for overseeing the overall artistic output of the Medicean state.

In Rome around a decade later, the Accademia di San Luca was established, which played an instructional role and was more interested in art theory than the academy in Florence. It was subsequently used as the model for France’s Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture, which was established in 1648. It was formed in an attempt to separate artists who were regarded as gentlemen pursuing liberal art from craftspeople who were involved in manual labor and was subsequently called the Académie des Beaux-Arts. The increased focus on the intellectual aspect of creating art had a significant effect on Academic art styles and subject matter.

After Louis XIV reorganized this academy in 1661 with the goal of controlling all French artistic production, an argument erupted among the academy’s members that defined artistic views for the remainder of that century. This “battle of styles” was over whether Nicolas Poussin or Peter Paul Rubens was a better model to emulate. Poussin’s supporters asserted that line ought to guide art because of its intellectual appeal, whereas Rubens’ supporters thought that color should take priority due to its emotional appeal.

The controversy was reignited in the early 19th century by the movements of Romanticism, as represented by Eugène Delacroix’s work, and Neoclassicism, as represented by Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres’ work.

There was also debate on whether it was preferable to study art by observing nature or by examining the great masterpieces of the past. Academies based on the French model sprung up all throughout Europe, imitating the methods of instruction and practices of the French Académie, such as the Royal Academy in England.

The Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, established in 1754, is a good example of a smaller country that accomplished its goal of establishing a national school and minimizing dependency on artists imported from other countries. The transition to academies resulted in it being more difficult for women to receive training, who had been excluded from most academies until the latter part of the 19th century.

The Development of the Academic Art Style

Many artists have produced between the two styles from the start of the Rubenist-Poussiniste debate. In a revived version of the argument in the 19th century, the art world’s focus and goals were to synthesize Romanticism’s color with Neoclassicism’s line. One painter after another was believed by art critics to have perfected this synthesis of styles such as Ary Scheffer, Théodore Chassériau, Alexandre-Gabriel Decamps, Francesco Hayez, and Thomas Couture. The secret to being a successful artist, according to William-Adolphe Bouguereau, is perceiving line and color as the same thing.

According to Thomas Couture, saying a painting had better line or color was foolish since although color seemed amazing, it relied on line for conveying it, and vice versa.

Historicism and Allegory

A further development during this era was the use of historical styles to illustrate the period in history that the work of art depicted, known as Historicism. This is most evident in the artwork of Baron Jan August Hendrik Leys and the emergence of the Neo-Greco style. Historicism also refers to academic art’s notion that one should absorb and integrate the developments of multiple prior art traditions. The world of art also began to place a greater emphasis on allegory. Color and line theories stated that by using these elements, an artist may exercise control over the medium and produce psychological effects in which emotions, themes, and concepts might be expressed.

As artists sought to put these theories into practice, the focus was placed on the artwork as a figurative or allegorical vehicle.

It was believed that representations in both sculpture and painting ought to reflect Platonic principles or forms, where one might see something abstract, some eternal truth underlying typical representations. In art, the movement shifted towards idealism, which is different from realism in that the characters represented were simplified and abstracted—idealized—in order to reflect whatever concepts they stood for.

This would entail both generalizing natural shapes and making them subordinate to the artwork’s theme and sense of unity. Because mythology and history were regarded as dialectics of concepts, an abundant source for allegory, themes drawn from these subjects were regarded as the most significant type of painting.

The Hierarchy of Genres

A genre hierarchy, established in the 17th century, was coveted, with historical painting (religious, classical, literary, mythical, and allegorical subjects), at the top, followed by genre painting, still-life, portraits, and landscape. Hans Makart’s works were typically larger-than-life historical dramas that dominated the style of Vienna culture in the 19th century and Paul Delaroche’s works were typical of French history painting.

All of these artistic trends were influenced by Hegel’s views, which argued that history was a dialectic of contrary ideas that ultimately came together in a form of artistic synthesis.

Additional Influences on Academic Art

During the era of Academic art, formerly unfashionable Rococo works grew popular again and subjects common in Rococo art, such as Psyche and Eros, were once again explored. Raphael was widely respected by the Academic art community for the ideality of his art, with some people even preferring him to Michelangelo. Under Jan Matejko, Polish Academic art flourished, and he was the person who founded the Kraków Academy of Fine Arts. Many of these pieces may be seen in Kraków’s Gallery of 19th-Century Polish Art at Sukiennice.

Academic art was influential not just in the United States and Western Europe, but also in other nations.

From the 17th century onward, approaches from Western academies dominated the creative setting of Greece. This was originally apparent in the Ionian School, and it subsequently became particularly apparent with the establishment of the Munich School. This proved to also be true for the countries of Latin America, which strove to emulate the culture of France since their revolutions were modeled after the French Revolution.

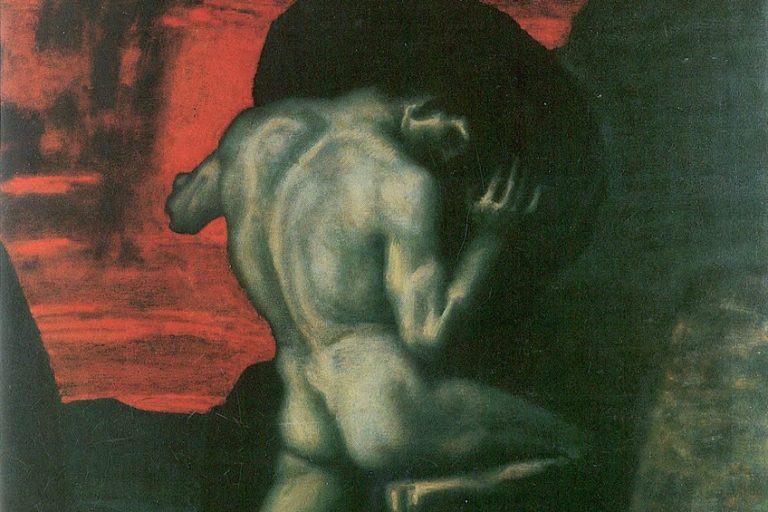

Characteristics of Academicism

Above, we explored the history of Academic art and how students were trained in these institutions. Next, we will look at the characteristics of Academic painting and sculpture. These characteristics included realism, idealization, and classical influences, among others. Academic painting prioritized accurate subject representation, typically representing situations from mythology, history, and everyday life with great attention to detail and accuracy. Academic art, although emphasizing realism, also idealized its topics. This meant that individuals were depicted with a particular focus on classical beauty and an elevated sense of harmony and perfection.

Ancient Greek and Roman art influenced academic art, and artists received instruction in the examination of classical architecture, sculptures, and literature.

To create believable and well-executed works of art, students had to also learn about anatomy, perspective, and chiaroscuro. Traditional mediums such as marble, bronze, and oils were popular among academics. Many academic artworks used mythology, historical events, and biblical themes as subject matter because they were considered culturally meaningful and worthy of artistic study. Artists meticulously prepared their paintings, taking into consideration elements such as proportion, balance, and the correct placement of figures to tell a particular story or express a certain message.

Training at Art Academies

Young artists received intense training for four years at these art academies. In France, only pupils who took an exam and had a letter of recommendation from a well-known art professor were admitted to the École des Beaux-Arts. The fundamental basis of academic art was paintings and sketches of nudes, and the technique for learning to produce them was well-defined. Students began by copying prints based on classical sculptures, becoming acquainted with the concepts of light, contour, and shade.

Copying was considered to be vital to academic education; by replicating the artwork of previous artists, one could absorb their methods of creating masterpieces.

Students presented these drawings for review from their professors in order to move to the next stage and each subsequent one. They would then sketch from plaster castings of iconic classical statues if approved. Only after mastering these abilities were they admitted to workshops where a real model posed for them. After 1863, the École des Beaux-Arts also started to teach painting. In order to learn how to paint, a pupil had to first prove his ability to draw, which was regarded as the basis of Academic painting. Only then could the student enter an academician’s studio to be taught to paint.

Competitions

Competitions with a specified theme and a certain permitted time frame monitored each student’s progress throughout the whole process. The Prix de Rome was the most prestigious competition, and the winner received a grant to pursue their studies at the Académie française’s school in Rome for five years.

An artist had to be a single male Frenchman under the age of 30 in order to compete. He also had to have met the École’s entry standards and the approval of a respected professor. The competition was fierce, with multiple phases preceding the final one, in which 10 contestants were locked away in studios for just over two months to produce their final historical paintings.

Because the winner was basically guaranteed a successful career, artists tried to persuade the members of the exhibition’s hanging committee to place their works at eye level. The greatest success for a professional artist was acceptance into the Académie française and having the bragging rights to be regarded as an academician.

Academic Art Exhibitions

Academic art had permeated European culture by the end of the 19th century and exhibitions took place often, with the Salon d’Automne and the Paris Salon being the most popular. These salons were massive events that drew a large number of both domestic and foreign visitors and around 500,000 people would typically attend a show over its two-month duration.

A successful exhibition at the salon provided a stamp of approval for artists enabling their works to be sold to the expanding number of private collectors, and Alexandre Cabanel, Bouguereau, and Jean-Léon Gérôme were prominent figures in this world.

Decline of the Salons

The Academy in France and other countries had lost touch with trends by the 1860s and was still promoting an outdated type of academic art and teaching system. Because of this inability to keep up with the contemporary trends in art, the Salon was viewed as becoming increasingly conservative, thus declining in popularity over time.

The first obvious indication of trouble occurred in 1863 when Emperor Napoleon III announced that a separate exhibition known as the Salon des Refuses would be held concurrently with the usual Salon to present every work that had been rejected by the Salon jury.

The Salon des Refuses eventually proved to be every bit as popular as the usual exhibition, which was a sign of things to come regarding the trajectory of the art world from that point onwards. Following that, more innovative alternative Salons, such as the Salon des Independants and the Salon d’Automne arose to offer the public a full range of modern art. From 1884 until 1914, these new Salons served to present to the public revolutionary new types of painting, such as Fauvism, Neo-Impressionism, and Cubism, to mention a few.

Criticisms of the Academic Art Style

Realist painters such as Gustave Courbet criticized the Academic art style for its use of idealism who saw it as being built on unrealistic clichés and reflecting legendary and mythological motives while ignoring contemporary social issues. The “false surface” of paintings was another source of contention for Realists. The objects portrayed were often slick, smooth, and idealized, with no discernible texture. Théodule Ribot, for example, fought against this by exploring unfinished and rough textures in his paintings.

The Impressionists, who supported painting outdoors precisely what the eye observes and the hand paints, criticized the polished and idealized painting technique of the Academic art style.

Although academic artists started their paintings by sketching and later painting oil sketches of their subjects, the Impressionists saw the excessive polish on the sketches as a visual lie. The artist would then create the finished painting after the oil sketch, modifying the image to match stylistic requirements and striving to elevate the imagery and add specific details.

The notion that still life and landscape belong at the bottom of the hierarchy of genres was likewise rejected by Impressionists and Realists. Most of the early avant-garde artists who revolted against Academicism, like the Impressionists, Realists, and others, started out as students in academic ateliers. Academic painters included Gustave Courbet, Claude Monet, Édouard Manet, and even Henri Matisse.

The Legacy of Academic Art

Academic art was further disregarded when contemporary art and its avant-garde gained influence and was considered styleless, clichéd, emotional, bourgeois, and conservative. The paintings were dubbed “grandes machines” because they were thought to produce a fabricated falseness using contrivances and gimmicks. The disdain for academic art reached a climax with the opinions of Clement Greenberg, a noted art critic who asserted that all academic art was “kitsch”. Other artists, such as the Symbolists and certain Surrealists, were more respectful of Academic tradition.

Academic art has been reintroduced into history texts and discussions due to Postmodernism’s attempts to provide a more complete, social, and pluralistic account of history.

However, while there is still a visible divide between postmodern and academic art, there are reasons to believe that things are going to change. This is regardless of the fact that non-academic art, as typified by artists such as Francis Bacon, Pablo Picasso, and Andy Warhol, is the most popular form of art in auction houses such as Sotheby’s and Christie’s. Academic art has also had a modest rebirth since the early 1990s, thanks to the Classical Realism atelier movement.

Furthermore, the work is acquiring greater public awareness, and although academic works used to bring in a few hundred dollars in auctions, many now sell for millions of dollars. So, why would academic art have a revival? The art taught at today’s art academies is nothing like the art that was taught 100 years ago. As a result, academic art has experienced incredible modernization in terms of both subject and instructional approaches. But one of the main reasons it may become relevant again is because abstract, hypermodern art now dominates: this is what is now considered popular. So maybe art collectors will want something new, such as a return to traditional ideals, at least in sculpture and painting.

Academic art was inextricably connected with formal art instruction. Students would be put through rigorous instruction at academies, learning the established methods and standards of the Academic art style. Academic art encountered increased criticism in the 19th century from developing avant-garde movements, as they opposed old traditions and tried to break free from academic restraints. As a result, academic art’s rule in the art world has since diminished. Academicism would eventually be succeeded by more innovative and diverse art styles like Cubism, Impressionism, and Surrealism. Yet, despite its decline, it has experienced something of a resurgence in the last few decades.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Are a Few Notable Academic Art Examples?

Academic art was a popular type of art in the 19th century that was connected to formal art education and conformity to predetermined artistic rules. Many notable artists, even those who would eventually be part of movements that opposed Academicism, received their artistic instruction at one of these prestigious academies. Some notable examples include Egypt Saved by Joseph (1827) by Alexandre-Denis Abel de Pujol, The Romans in their Decadence (1847) by Thomas Couture, The Empress Eugenie Surrounded by her Ladies in Waiting (1855) by Franz Xaver Winterhalter, The Death of Orpheus (1866) by Émile Lévy, The Excommunication of Robert the Pious (1875) by Jean-Paul Laurens, and Ulysses and the Sirens (1891) by John William Waterhouse, among many others.

What Is the Academic Art Style?

Academic painting and sculpture were popular in the 19th century, notably in Europe, and conformed to a set of established rules and ideas. Nudes were particularly important in the initial study of art in Academicism, and drawing was regarded as the fundamental basis of art in general. Academic art has to do with formal instruction, and students would have to go through intense training in order to meet the standards of the academy. Yet, by adhering to their standards and winning important competitions, artists could essentially ensure their place in the world as successful artists.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Academic Art – A Look at the Canvas of Intellectual Expression.” Art in Context. December 7, 2023. URL: https://artincontext.org/academic-art/

Meyer, I. (2023, 7 December). Academic Art – A Look at the Canvas of Intellectual Expression. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/academic-art/

Meyer, Isabella. “Academic Art – A Look at the Canvas of Intellectual Expression.” Art in Context, December 7, 2023. https://artincontext.org/academic-art/.