Neo-Impressionism – An Exploration of Neo-Impressionism Art

Neo-impressionism art began when Georges Seurat and a number of his colleagues proposed a new approach to color and light perception in painting. They based their techniques on revolutionary scientific discoveries related to “optical mixing”, which would decode their coloristic experiments on canvas through the viewer’s eye and brain.

The Nuanced Impact of Neo-Impressionism

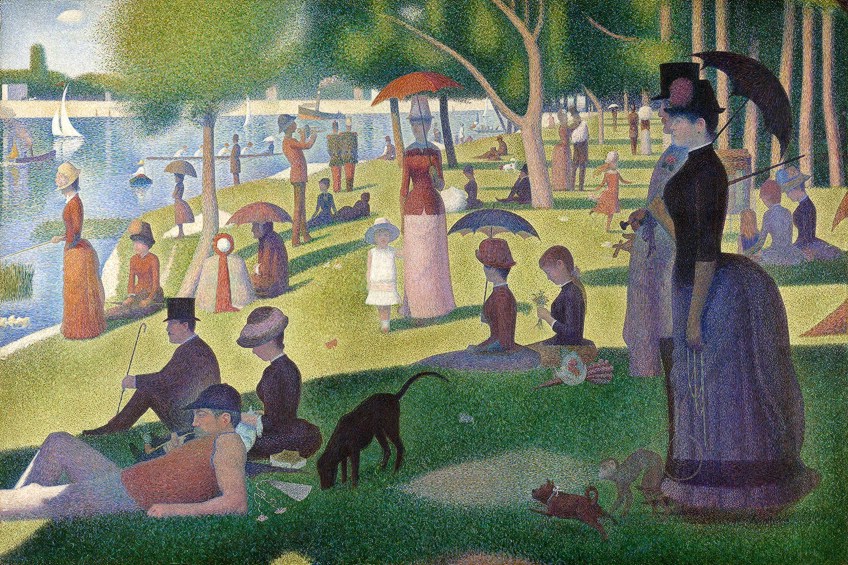

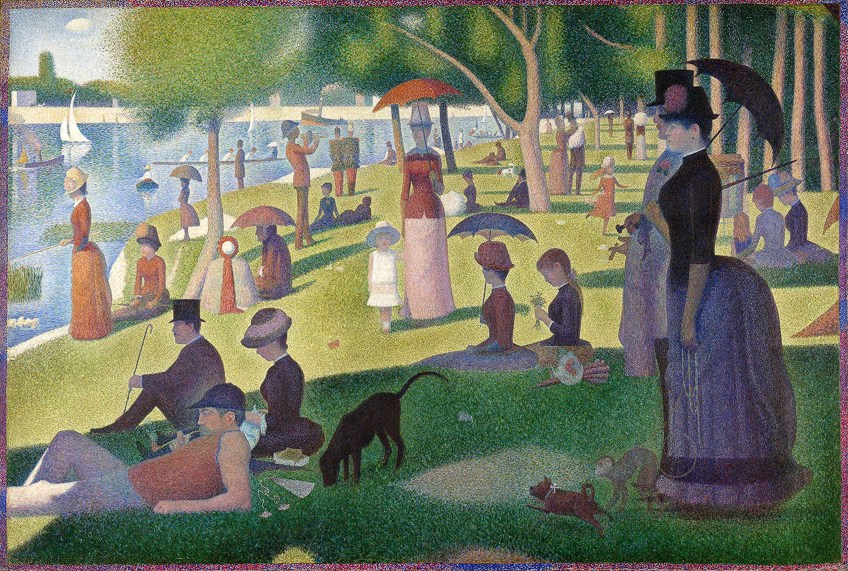

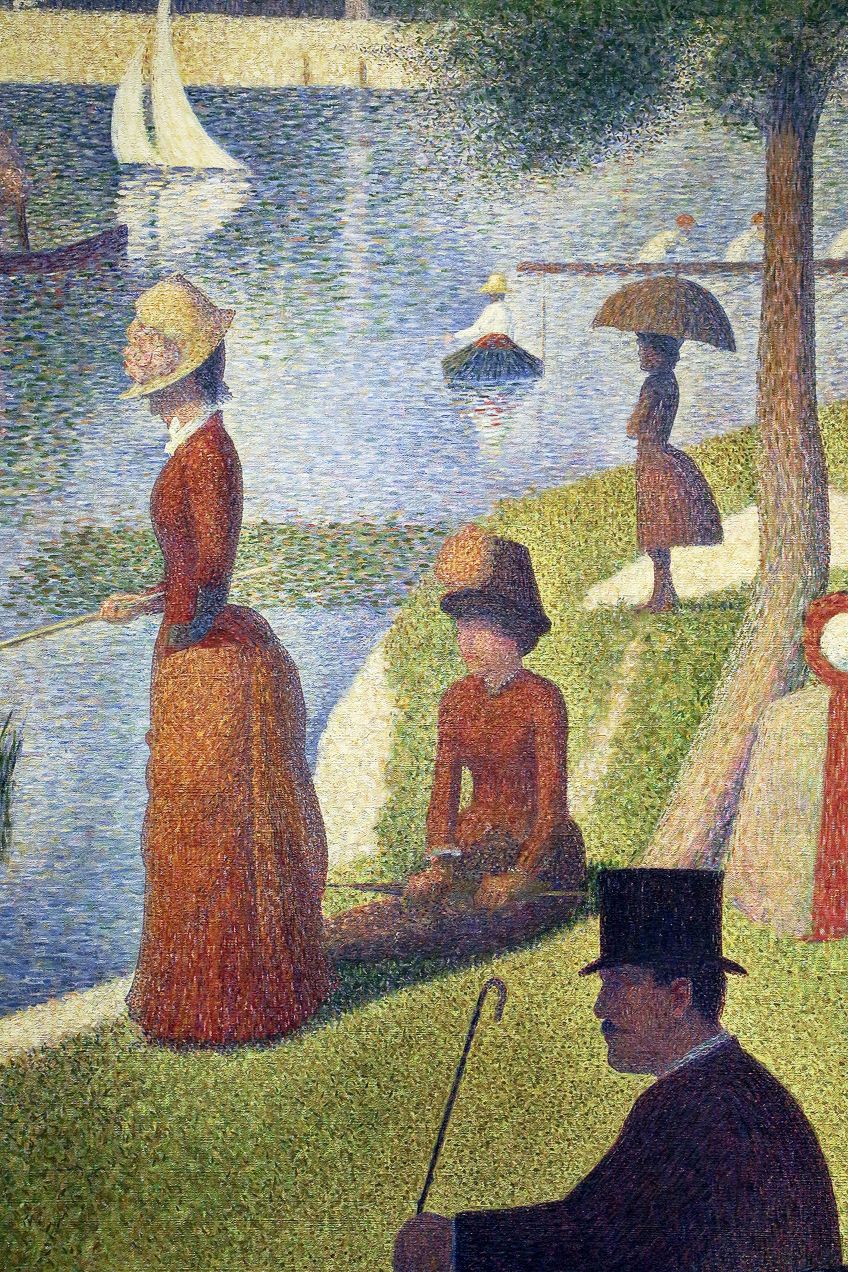

Neo-impressionism as an avant-garde art movement was launched at the 8th and last Impressionist exhibition of 1886, where its founding figure Georges Seurat presented his monumental painting A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte (1884 – 1886). Seurat’s new aesthetic became something of a standard for the movement.

Neo-Impressionism was at its height between 1885 and 1894, with Paul Signac later becoming the movement’s leading figure.

What Is Neo-Impressionism?

Neo-Impressionism is defined as a style of painting that emerged in France during the 1880s, and goes by many names. Georges Seurat called it Chromoluminarialism, while Paul Signac made his own distinction with his term Divisionism. Somewhere along the way, we have Pointillism and even post-Impressionism.

One of the movement’s fiercest advocates, critic Félix Fénéon, coined the term “Neo-Impressionism”, which encompassed all of the above.

Neo-Impressionism came to signify the art movement founded by a small group of artists, including Georges Seurat, who developed a conceptual and technical approach to painting based on scientific optical theories. They aimed to impose experimental interventions on what the Impressionists before them had done and to create supremely luminous paintings.

Many Neo-Impressionism artists were a generation younger than the Impressionists, thus, they would have been familiar with the Impressionists who were still active. In their desire to depict contemporary, often outdoor subjects, and their focus on light and color, they were incredibly similar to the Impressionists.

But Neo-Impressionism artists wanted to honor Impressionist traditions through scientific means. They renounced the Impressionists’ emphasis on the artistic brushstroke and were not interested in utilizing its looseness to achieve spontaneous-looking images.

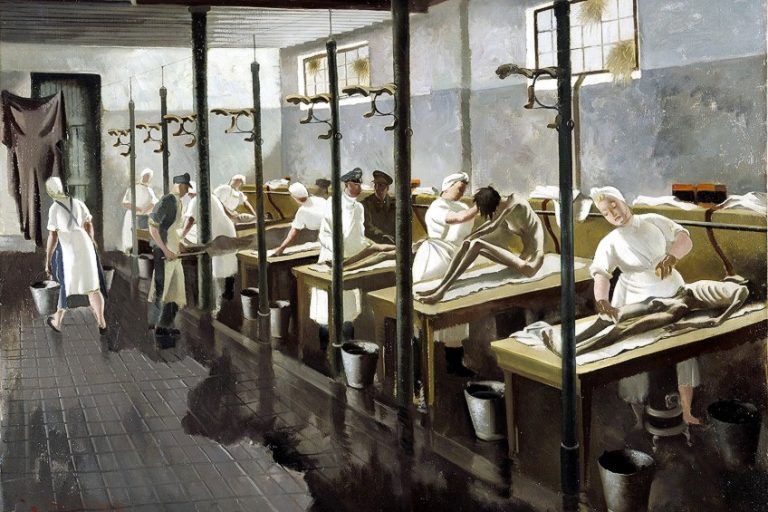

Unlike the Impressionists who were all about ethereal light and moments, the Neo-Impressionists wanted to render logical and preplanned compositions to address the political context of the day which included industrialization and exploitation of the working classes.

The question “what is Neo-Impressionism” can be answered by a core technical concept of Neo-Impressionism definition was visual mixing. The use of contrasting colors and a fragmenting technique was rooted in the Neo-Impressionists’ interest in color science.

They avoided mixing color on the palette unless it was with white or an analogous color. Instead, they would place small areas of color next to each other on the canvas, manipulating the appearance of adjacent colors.

Divisionism

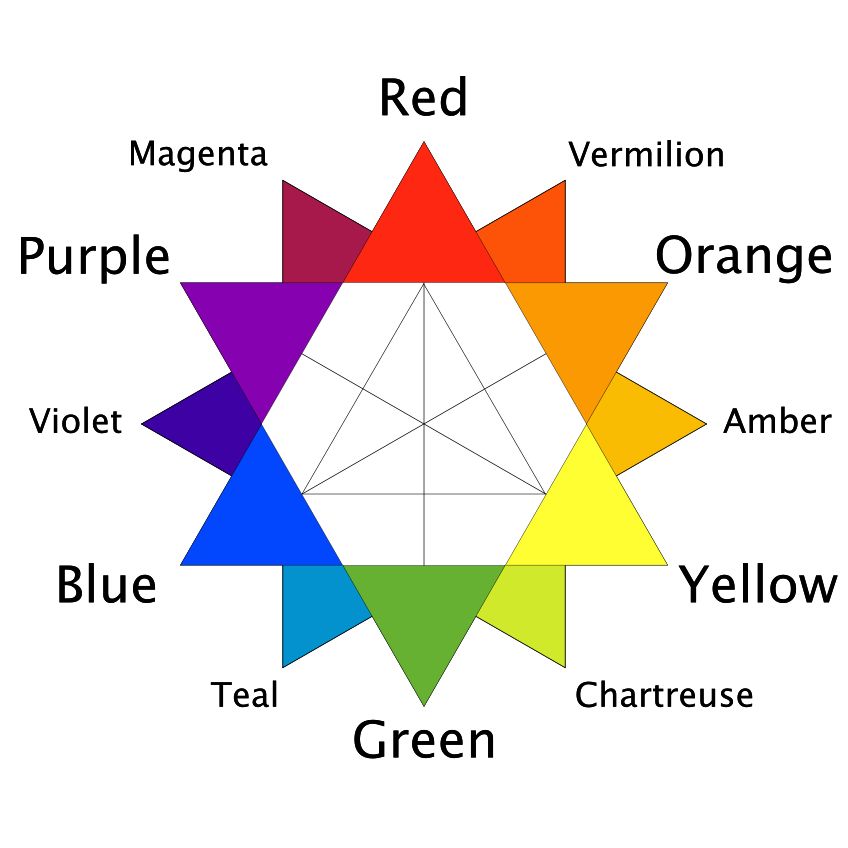

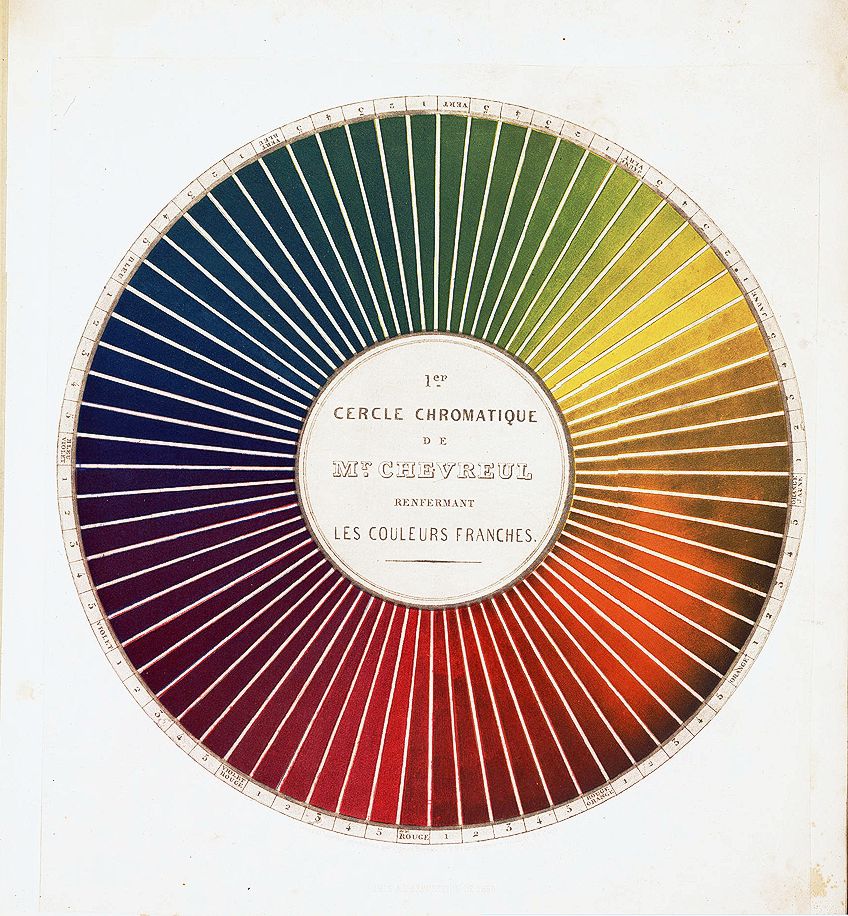

Charles Blanc’s color wheel was influential in the conceptualization of Divisionist theory. Blanc drew from theories by chemist Michel Eugène Chevreul and colorist Romantic painter Eugene Delacroix to hypothesize the notion of mélange optique or optical mixing.

According to Paul Signac, Divisionism would produce more vibrant colors than the traditional pigment mixing process.

In a book published in 1879 and translated into French in 1881, Charles Blanc provided a drawing of little stars on the right and little dots on the left to illustrate the process of mixing colors through perception instead of on the palette. He referred to John Ruskin’s book The Elements of Drawing, which advocated a similar technique and which Impressionists like Claude Monet and Edgar Degas had also praised.

Inspired by this illustration, Divisionism art would become characterized by patches of individual colors which interacted optically with one another.

By placing separate colors on the canvas, a new color was produced. This blended color was only present in the eye of the beholder when viewing the painting at a distance. In this way, Divisionists believed they were achieving the maximum luminosity according to science.

Pointillism

The Neo-Impressionist technique can be summarized as the use of a divided touch, but there are various ways of achieving this. While Pointillism was the most common technique, Paul Signac pointed out that Pointillism was but one of the many methods that could be explored in Neo-Impressionism. For Signac, the dots were not sufficient without the technique of color contrast.

Neo-Impressionism’s key techniques were based on French chemist Michel-Eugene Chevreul’s ‘law of simultaneous contrast’, which states that where eyes see two opposing colors simultaneously, these colors appear as different as possible in optical composition and in tone.

Thus, Divisionism art was an aesthetic that incorporated this theory, while Pointillism was a technique for executing it. In the case of Pointillism, the technique was an application of small dots or points that when viewed collectively, would allow the viewer’s eyes to complete the composition.

Pointillism was more concerned with form and composition.

As it wasn’t restricted to the dot, Divisionism delivered a dynamic image whereas Pointillism could convey a calm and static look. Georges Seurat once explained that through Pointillism, he wanted to emulate the effect of a Greek Frieze.

The Founding Fathers of Neo-Impressionism Art

Neo-Impressionism, and its many followers, worked hard to establish a new and scientific approach to painting that essentially renounced the style that other Impressionists greatly admired. Below, we will be taking a look at two of the most important figures from the Neo-Impressionism art movement, along with some of their notable contributions.

Georges Seurat (1859 – 1891)

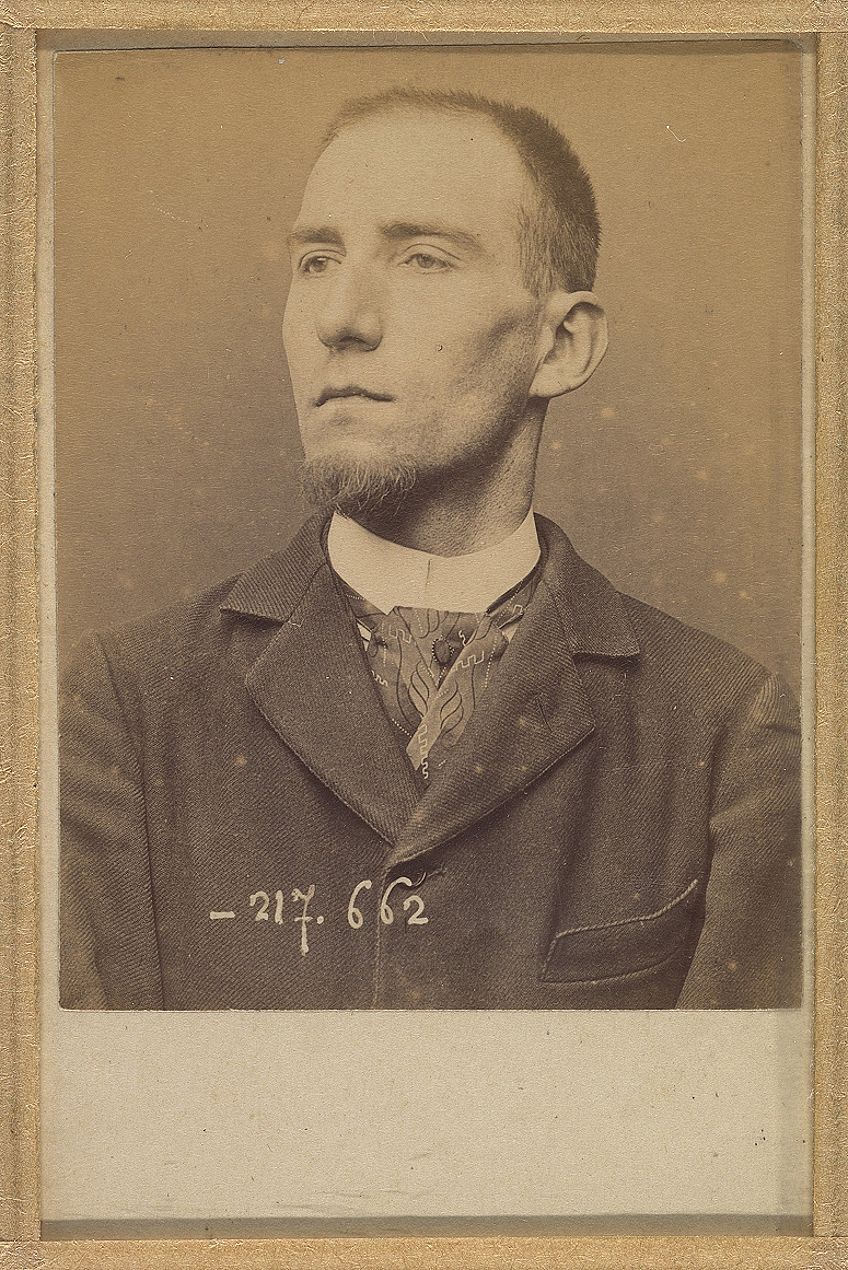

Georges Seurat received academic training, but only for a year. He found academic art restricting, so he joined the army. His military career was even briefer but it exposed him to the Impressionists. Painters like Claude Monet and Lucien Pissarro, with their organic colorists and modern subject matter, were a great inspiration to the young painter.

From then on, he would work in several different styles but it is for his pioneering of Neo-Impressionism that he would become best known.

Though his sources were somewhat contradictory, Georges Seurat embraced Michel-Eugene Chevrelle’s theories, which the Neo-Impressionists knew through the art historian Charles Blanc. He used these theories to establish what he called Chromoluminarism around 1884.

Seurat and his fellow Neo-Impressionists experimented tirelessly to push beyond the bounds of Impressionism. Unlike the Impressionists, Seurat painted mainly in his studio though he produced hundreds of sketches en Plein air which greatly outnumber his finished paintings.

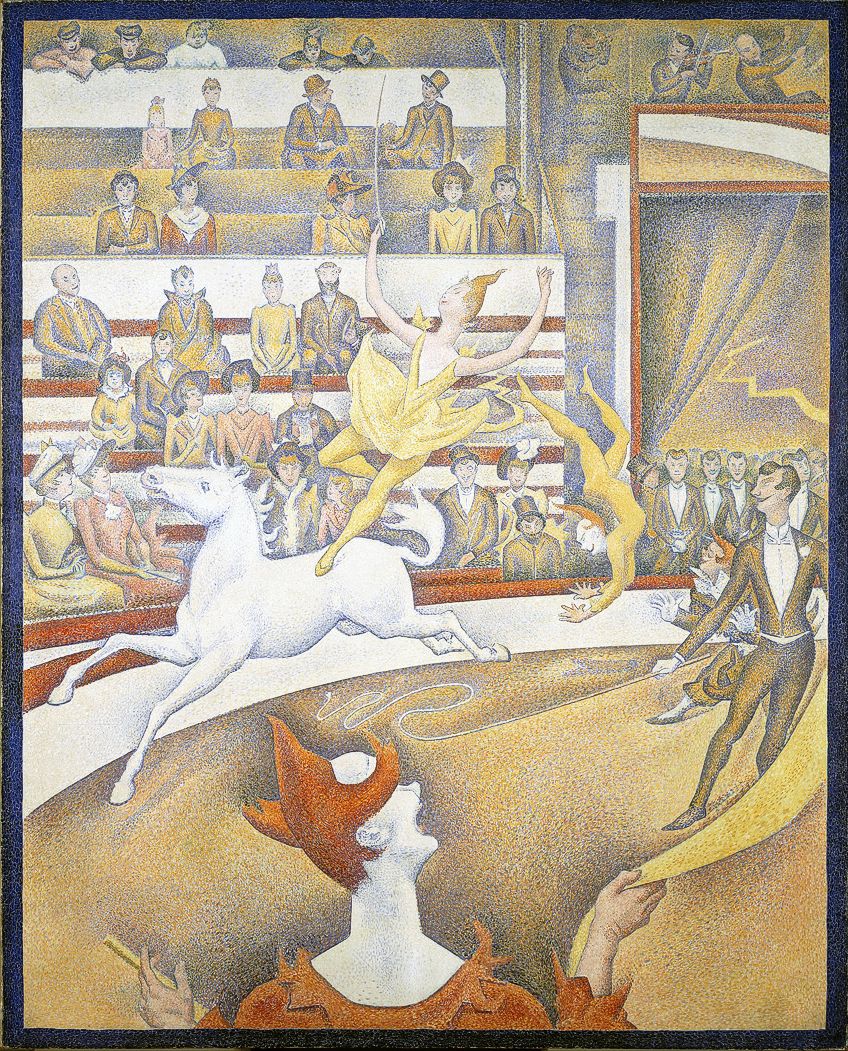

His final painting The Circus (1890–1891) remains unfinished. It is a compelling insight into his skill and intention.

The balancing of blue and yellow harmonies and the dynamism of shape evoke motion and energy in the static parameters of his demanding style. He encoded social commentary into this work. Picturing upper-class figures in the front row seats and working-class figures in the nosebleeds above.

Seurat’s sudden death in 1891 dealt a devastating blow to the Neo-Impressionist cause. Seurat was in his early 30s and the cause of death was an unknown infection. Despite his short career, his oeuvre and legacy prove that he was a prolific artist and visionary.

A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte (1884 – 1886)

| Name | A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte |

| Year | 1884 – 1886 |

| Size | 2,08 m x 3,08 m |

| Medium | Oil paints |

One of the founding artworks of the movement was made by Georges Seurat. A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte (1884-86) debuted at the 8th and final Impressionist exhibition in 1886. The painting was large for Impressionist standards. It launched the 26-year-old artist into the limelight and is arguably the most historically significant out of that exhibition.

When Seurat began the painting in 1884, he had used small brushstrokes of alternating colors. Upon revisiting the painting in the winter of 1885-1886, he reworked it following his new rebellious form of Impressionism inspired by optical theory. It was not until he was close to finishing A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte in 1886 that Seurat came up with the Pointillist dot technique, which he originally called Chromoluminarism.

Pointillism was the key to correcting the large canvas without having to repaint it. Seurat repeatedly juxtaposed miniature dots in contrasting colors which harmonized the canvas giving it a luminous hue. He visited the park repeatedly to meticulously capture the light of the landscape. During these trips, he completed numerous drawings and sketches before returning to the painting. His sketches demonstrate how devoted he was to Chromoluminarism. He spent two years working on this painting.

The setting of this piece is the island of La Grande Jatte located just west of Paris. The park had been an industrial area for many years. However, when Seurat started this painting in the spring of 1884, it had become a rustic hotspot outside the city where wealthy Parisians retreated on sunny afternoons.

The blues, greens, yellows, and reds are applied more or less unmixed. Instead of mixing, each color is placed separately in relation to the next. The water has multitudes of dots in lead white, emerald green, and ultramarine blue which Seurat placed over one another to build layers that combine in the eye to produce the desired effect.

The overall composition of dark and light ebbs flaunts the luminous qualities of the Neo-Impressionist style.

As was the case with Seurat’s first major work Bathers in Asnières (1884), he showed us a glimpse of the complex social world of the day. It is interesting that in Bathers in Asnières, the relaxing workers of Paris are bathed in full sunlight while almost every figure in La Grande Jatte is protected by the shade from trees and umbrellas.

Despite the island of La Grande Jatte being open for all the people in Paris, most of the folks in the image are well to do. The 48 figures include dandily dressed gentlemen, ladies in fashionable finery, well-off couples and their presentable children, even a trumpeter serenading two soldiers standing to attention.

Towards the center of the painting is a young girl in red who appears to be the only figure in motion.

Seurat slyly jabs at the morality of the class with two of the female figures who convey signs of prostitution, a favorite pastime for the wealthy of the day. There is a woman fishing and another taking her pet monkey for a walk.

The woman extending her fishing pole onto the water on the left could be a hint at her fishing for clients. The woman with the pet monkey betrays a bit of wordplay. The French word singesse, meaning female monkey is also the slang for prostitute.

Seurat’s Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte, read in tandem with Bathers in Asnières, is an interesting insight into what life was like in Paris then. Bathers showed us the working class while La Grande Jatte depicted the world of the wealthy on the other side of the river. This work used scientific techniques to expose disparities between different parts of society in the rapidly modernizing Paris of the day.

Once again as in Bathers, there is a static quality to the painting except in La Grande Jatte Seurat enhanced it to speak to the sense of social rigidity in the upper class. The scene may appear busy at first, but Seurat’s Pointillism highlights his subjects’ isolation. He is depicting the bourgeoisie as disconnected from the rest of society and each other. The frozen quality of the figures produced an element of timeless irony.

La Grande Jatte properly launched Seurat’s career. But following his death in 1891 the painting was rarely seen for nearly three decades.

Fortunately, in 1924, it was purchased and then loaned to the Art Institute of Chicago, where it remains to this day. La Grande Jatte has become one of the most memorable modernist masterpieces, and has been thoroughly referenced in art and pop culture alike.

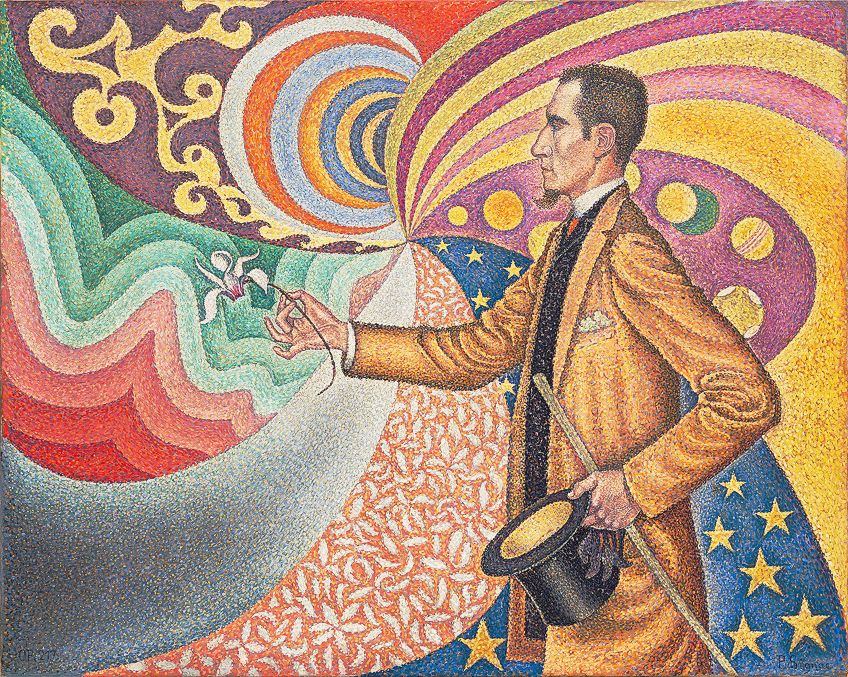

Paul Signac (1863 – 1935)

Paul Signac met Seurat at the founding event of the Societe des Artistes Independants in the summer of 1884. Having already seen Seurat’s work in the Independent Salon of 1884, Paul Signac promptly converted to the Neo-Impressionist approach.

As he was four years older than Signac, Seurat was able to impart his knowledge. Being from an upper-middle-class family, Signac had the means and the time to assist Seurat on his mission to develop the Neo-Impressionist methods. Unlike the reclusive Seurat, Signac was an extrovert and extremely well connected.

It was Paul Signac who publicized Seurat’s Neo-Impressionist ideas. This is why Paul Signac is considered one of the founding figures of Neo-Impressionism.

Their characters were so compatible Signac would remain Seurat’s closest creative comrade until his untimely death. After Seurat died in 1891, Paul Signac stepped in as Neo-Impressionism’s chief theorist. Under Signac’s leadership, the movement became more outspoken about their critique of the modern world and their connection to anarchism came to the fore.

Signac’s continued advocacy of Neo-Impressionism was vital to the movement’s survival.

He guided the next generation of painters, even working with Henri Matisse during the summer of 1904 when he was painting his own Pointillist work Luxe, calme et volupté (1904). But after moving to Saint-Tropez in his old age, the movement dwindled. Paul Signac would continue painting in the Divisionist style until he died in the 1930s.

From Eugène Delacroix to Neo-Impressionism (1899)

Paul Signac’s book D’Eugène Delacroix au Néo-Impressionnisme (1899) or “From Eugène Delacroix to Neo-Impressionism”, coined the term “Divisionism” and is widely considred as the Neo-Impressionist manifesto. It was published in 1899 and although that was already five years after the heyday of the movement, many artists read it and were influenced by the aesthetic.

The book was a defense of Neo-Impressionism, which was still highly criticized at the time. Signac used the book to trace connections to the great colorist Delacroix in an effort to validate the Neo-Impressionist aesthetic.

Delacroix and Signac simultaneously rebuked brushstroke and praised the touch. To understand Neo-Impressionism then, one had to distinguish between touch and brushstroke. Touch was the minimal intervention on the surface of a canvas with the paintbrush. This was Delacroix’s objective.

Brushstroke in contrast to touch required movement. Though it did not require much physical exertion, the hand needed to make a gesture. Evidently, the brushstroke was far too subjective a gesture for Delacroix. The idea was that brushstrokes removed the viewer’s focus from the painting and directed it towards the painter’s hand. Heeding Delacroix’s teachings Signac wrote that: “Neo-Impressionist painters refused to be seduced by the charm of the brushstroke.”

While the book begins with the trend of Signac and Delacroix’s criticism of the brushstroke and admiration of the touch, its later sections emphasize the disparities. Signac visualizes a transition from Delacroix to the Impressionists and then to the Neo-Impressionists.

Delacroix had written: “The touch is a means amongst others to render the thought in the painting. Color is another means to produce the same effect. So, an analogy could be made between color and touch.” Signac used this to argue that before Neo-Impressionism the touch was motivated. Because of the artificiality of the Neo-Impressionists’ divided touch, the touch had become separated from the narrative of the painting. Completely removing the means from the content encouraged painters to embrace the possibilities of painting for painting’s sake which would eventually lead to abstract painting.

Criticism and Contradiction

Seurat’s friend and art critic Félix Fénéon popularized the term Neo-Impressionism. He had used it to describe the work presented by Georges Seurat at the 8th and final Impressionist exhibition in 1886. The term triumphed over the other terms for the style such as Pointillism, Divisionism, and Chromoluminarism. Fénéon’s championing attracted more artists to paint in the style, including Camille Pissaro who excelled in Neo-Impressionism.

During his lifetime Seurat had attracted more attention from critics than Signac, whose work was often referenced only in relation to his friend’s. Seurat’s death corresponded with the decline of Neo-Impressionism. The inherent rigidity of the painting style made many painters who had experimented with it eventually abandon and even criticize it.

Although they had claimed their style was founded on scientific principles, critics saw evidence that Neo-Impressionists had misinterpreted optical theories. Ultimately, the Neo-Impressionists did not achieve convincing optical mixing and could not prove that their methods ensured greater luminosity as that was a subjective premise.

The science stipulated that enhanced luminosity was possible under the condition of colored light, not dots of painted color. The Neo-Impressionists were attempting to intensify the luminosity of two adjacent plain pigments while preserving their individuality. In actuality, the resulting luminosity amounts to no higher than the average of their separate luminosities.

Less discerning critics simply slammed Pointillism for its failure at naturalism. Of course, reality doesn’t appear as multicolored dots. These critics lambasted the Neo-Impressionists’ core concept of touch. To fully appreciate what was being represented, they wanted the touch to be transparent.

Everything is Illuminated

By the turn of the century, Neo-Impressionism had been replaced by newer movements such as Cubism, which adopted the separation of color into its own spatial organization, and Fauvism, which borrowed the evocative use of color, freeing it from Neo-Impressionism’s restrained scientific methods. These styles were much easier to practice and understand.

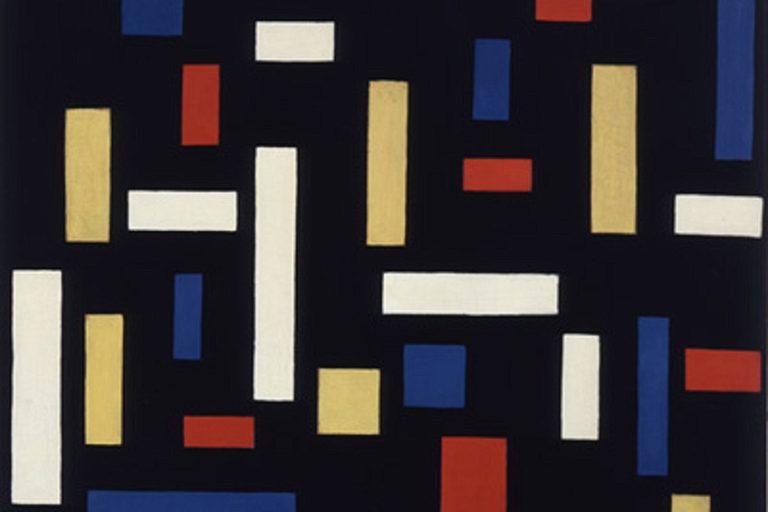

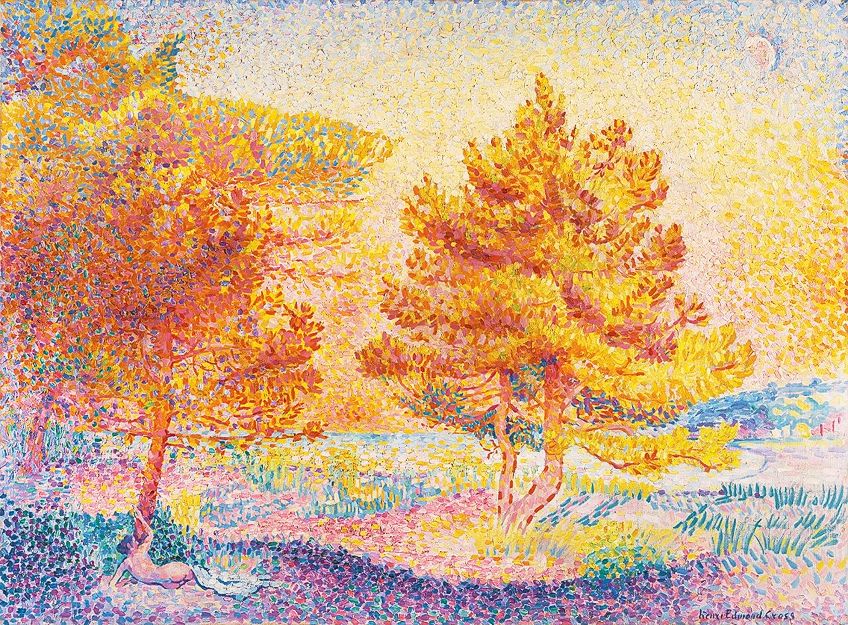

In addition to Signac, other artists who experimented with Neo-Impressionist techniques included Lucien Pissarro and his father, Camille Pissarro, along with Albert Dubois Pillet, Maximillian Luce, and Henri Edmund Cross. The Neo-Impressionist influence can even be traced through to the works of Vincent van Gogh, Henri Matisse, Piet Mondrian, Robert Delaney, and Pablo Picasso.

Neo-Impressionism also set a precedent for the integration of art and politics. In the 20th century, competing ideologies sought visual languages which reflected their values. Artists from Picasso and his association with communism to the Italian Futurists’ connection to fascism would no longer shy away from using their art to shed light on their political beliefs.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is the Difference Between Neo-Impressionism, Divisionism, and Pointillism?

Divisionism and Pointillism are both sub-styles within Neo-Impressionism. Pointillism is defined specifically as the use of dots of paint and is not necessarily focused on the separation of colors. Divisionism, on the other hand, developed specifically as a technique of optical color mixing.

Is Neo-Impressionism the Same as Post-Impressionism?

The answer to this question is both yes and no. While the terms are often conflated, it is not true that they are one and the same. Neo-Impressionism is a sub-movement of post-Impressionism. In essence, they are related but are not completely the same.

What Is Neo-Impressionism Visually?

There are often minuscule points, patches, or dots of pure color that are applied all over the canvas, which constitute the image. These colors are often placed separately in contrast to one another, allowing color mixing to take place in the viewer’s brain when looking at the artwork.

Were the Neo-Impressionists Anarchists?

Though unlikely to throw bombs, many Neo-Impressionists embraced the anarchist ideal of a harmonious society based on individual autonomy. In the eyes of painters like Signac and critics like Feneon, Neo-Impressionism became a visual analogy for the anarchists’ political goals.

Heidi Sincuba was the Head of Painting at Rhodes University from 2017 to 2020 and part of the first Artist Run Practice and Theory course at Konstfack in Stockholm, 2021. They completed their BFA at Artez Arnhem in the Netherlands, MFA at Goldsmiths University of London, and are currently a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Cape Town.

Heidi Sincuba’s own practice explores fugitivity through painting, drawing, text, textiles, performance, and installation. This praxis is founded on a conceptual intersection of biomythographic experimentation, existential automatism, and African ancestral knowledge systems. These methodologies of multiplicity result in a fluid and speculative aesthetic, continually manifesting and metamorphosing its material conditions.

Learn more about the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Thembeka Heidi, Sincuba, “Neo-Impressionism – An Exploration of Neo-Impressionism Art.” Art in Context. February 24, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/neo-impressionism/

Sincuba, T. (2022, 24 February). Neo-Impressionism – An Exploration of Neo-Impressionism Art. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/neo-impressionism/

Sincuba, Thembeka Heidi. “Neo-Impressionism – An Exploration of Neo-Impressionism Art.” Art in Context, February 24, 2022. https://artincontext.org/neo-impressionism/.