Fresco Painting – The Age-Old Art of Applying Paint to Plaster

Since Classical antiquity, fresco painting has been a popular art form. The early and late Renaissance period saw an incredible insurgence in fresco painting techniques with works like Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel ceiling. The fresco style of painting is most suited to large-scale wall pieces and is celebrated as one of the most incredible mural-making techniques in art history. In this article, we will discuss the many fascinating aspects of fresco painting, as well as the different types of fresco methods, its origins, and a few masterpieces in art history that were created in the fresco technique.

What Is a Fresco?

Many consider fresco and mural painting to be one and the same but this is not quite true. While almost all fresco paintings are murals or large-scale paintings that are executed on walls or ceilings, murals are not necessarily frescos. The fresco art definition is slightly different from that of murals. So, what is a fresco?

The term “fresco” or “fresh”, as it is understood in Italian, stems from the practice of painting that involves a mixture of water and pigment applied onto a freshly plastered wall.

As the lime-based plaster dries in the air, carbonation fuses the pigment particles within the plaster. As such, the fresco painting technique actually increases the integrity of the wall and the painted image. The glory of fresco painting lies in its longevity. Fresco paintings outlive almost every other medium. Many fresco paintings from Ancient Greece, Rome, India, Sri Lanka, and Egypt remain in relatively good condition today. Some contemporary mural artists continue to use fresco techniques because of its superior durability to weathering.

Different Fresco Painting Techniques

There is no one fresco art definition. In fact, there are three different types of fresco painting techniques with differing methods of adhering pigment to the wall plaster. Buon or “true” fresco artists paint with a pigment-water mixture that is applied directly onto the freshly applied lime plaster. Secco fresco painting uses pigment mixed with a binder that is applied on a dry plaster canvas. Finally, the mezzo fresco painting is somewhere in the middle of the previous two. Artists creating mezzo frescos paint on plaster that is almost dry but not quite. Below, we will dive into the different fresco painting techniques that will help you understand the benefits of fresco painting.

Buon Fresco Painting Techniques

Buon fresco painting is the oldest, most durable, and common type of fresco painting. The paint mixture relies on a combination of pigment and room temperature water. The canvas for Buon fresco painting is a very thin layer of wet plaster, called the intonaco. The intonaco itself binds the pigment to the wall, so there is no need to use a binder.

The intonaco tends to dry within a few hours and cannot be fixed by simply painting over it, so artists need to work quickly and accurately with this type of fresco.

There are three general steps that buon fresco artists need to follow to ensure the integrity of their painting. The first step in painting buon fresco is the application of a rough underlying layer known as the arriccio. The arriccio layer is typically a mixture of sand, marble dust, and plaster, which is applied to the entire portion of the wall and is left to dry for a few days. The number of arriccio layers that can be applied varies depending on the artist’s preference but it can include up to three layers.

Once the arriccio layer has dried, the artist can transfer the sketch of their composition, which was also described as the preparatory cartoon, onto the wall.

Many early artists used sinopia, a red pigment, to outline the plan for the fresco. Other modern techniques include placing a paper drawing onto the wall and pricking over the primary lines with a point, after which a bag of soot would be pressed over the paper to reveal the dotted lines. On the day of painting, the artist trowels the smoother intonaco plaster onto the wall area, which they could finish in a day. The name for this “day’s work” portion of the wall is called giornata. You can typically see a faint seam separating the different giornatas on very large frescos. Sometimes, artists would plan the giornatas alongside figures within the composition but typically most artists start at the top.

Perhaps the most significant restriction when using buon fresco techniques is the rapid drying time of the intonaco plaster layer. Typically, the layer of plaster will take between 10 and 12 hours to dry. Traditionally, buon fresco artists will only begin painting around two hours after applying the intonaco and will finish two hours before the final drying time.

After the giornata plaster has dried fully, the artist cannot continue to paint and must remove any unpainted intonaco. The carbonation of the lime plaster as it air-dries is an essential part of the buon fresco process.

Secco Fresco Painting Techniques

Fresco secco techniques completely eradicate the time pressure of working with buon fresco methods. The canvas for secco frescos is a dried plaster wall and the paint contains the color pigment and a binder such as tempera egg yolk, oil, or glue.

While secco fresco painting does away with the faff of preparing the plaster and the need to work at speed, it does sacrifice durability.

Artists often used fresco secco techniques to fix or build extra elements into buon frescos. Blue pigments, for example, were difficult to achieve using buon fresco methods because of the plaster’s alkalinity. It is becoming increasingly obvious that many early Renaissance painters used secco techniques because of the broader range of colors available.

While buon fresco painting requires a smooth intonaco surface, secco fresco techniques work best on a roughened plaster surface.

The rough surface increases the durability of secco but these frescos are more vulnerable to dampness than buon techniques. For full secco frescos, the intonaco has a rough finish and is left to dry thoroughly. The surface is then made extra rough by rubbing it with sand. The artist can paint the intonaco surface in the same way that they would when working with a wooden panel or traditional canvas.

Not only is the process of secco painting faster, but artists can also correct mistakes with more ease. Additionally, the difference in color between the wet paint and the final composition is not as significant as buon fresco techniques. Raphael and Michelangelo frequently used secco techniques in their frescos, and the artists often created indentations on the plaster surface to create more depth.

Mezzo Fresco Painting Techniques

The final form of fresco painting is the mezzo technique. The mezzo fresco technique is a combination of the buon and secco styles. Artists paint onto dry intonaco, which is not entirely dry but close to complete dryness so that the pigment is absorbed only slightly into the plaster.

This fresco technique became increasingly popular during the early Renaissance and had replaced buon techniques almost entirely by the beginning of the 17th century.

There are several advantages to using mezzo fresco techniques, with the foremost advantage extending the painting time. The extension of painting time has the additional advantage of allowing artists to complete larger fresco areas in a single sitting. Landscape paintings, in particular, benefited from the mezzo techniques as the distinctions between buon giornatas would ruin the continuity of the composition. Mezzo fresco techniques were popular among many late Baroque artists, including Gianbattista Tiepolo.

The Colorful History of Fresco Painting

While fresco painting techniques came into their own during the Italian Renaissance, the earliest examples date back to Classical antiquity. Additionally, while many people tend to view fresco paintings as traditional Western, the techniques have historically been used throughout the world. We begin our exploration of the history of fresco painting in Egypt and finish by considering some contemporary fresco styles.

The First Fresco Paintings

As far as we know, the earliest fresco examples found in the Hierakonpolis tomb in Egypt date back to between 3500 and 3200 BCE. Other early frescos in Israel, Egypt, and Crete date back to 2000 BCE. These frescos typically adorn the walls of tombs and palaces and depict various parts of ancient life, including battles and farming.

The “Investiture of Zimri-Lim” is one fantastic fresco example from 18th century BCE Mesopotamia. These earlier tomb frescos, particularly the ones in Egypt, used the secco fresco technique.

In terms of buon fresco techniques, the oldest frescos date to the Aegean civilizations in the first half of 2000 BCE. The Toreador is perhaps the most famous early buon fresco and depicts men jumping over large bulls as part of a sacred ceremony. Many of the oldest buon frescos, dated to the Neo-Palatial era, are found on Santorini, a Greek island. Other similarly dated frescos in Morocco and Egypt are under speculation in terms of their origins. Some art historians believe that many of them may have reached these shores through trade from Crete.

Frescos From Classical Antiquity

Many artists from the ancient Greek period painted frescos but unfortunately very few remain today. A Magna Graecia tomb known as the Tomb of the Diver, found in southern Italy in 1968, contains ancient Greek frescos dating to 470 BCE. These frescos present social and everyday life scenes from ancient Greece. One fresco, for example, depicts a young man diving into the ocean. Another fresco in the same tomb shows a collection of men resting at a symposium. The Tomb of Orcus in Italy includes other frescos from the Etruscan era.

The buon frescos found in the ruins of Herculaneum and Pompeii demonstrate the Roman style of fresco painting. In the catacombs beneath Rome, there are examples of late Roman Empire frescos. Other Roman frescos depicting Byzantine icons exist in Antioch, Crete, Cappadocia, and Cyprus.

While Classical antiquity typically refers to ancient Rome and Greece, this period also saw fresco paintings in Sri Lanka and India.

There are over 20 different locations in India with preserved frescos that date between 200 and 400 BCE. Many of these frescos adorn the ceilings and walls of rock-cut cave temples like those in the Ajanta Caves. The frescos in this cave are the oldest in India and depict the Buddha’s life. In Sri Lanka, the Sigiriya frescos date to the reign of King Kashyapa around 500 CE. Most art historians believe that these frescos depict the women of the king’s court. The style of these frescos is similar to the Gupta painting style found in the Ajanta Caves. The Sigiriya frescos use a fresco lustro technique that involves a small amount of glue or binding agent.

The Rebirth of Renaissance Frescos

From famous wall painting legends like Masaccio and Correggio to Fra Angelico and Giotto, the early Renaissance period marked the beginning of some of the world’s best fresco painters. It was in the hands of Italian Renaissance painters that fresco really came into its own. Many art historians consider the Italian Renaissance to be the peak of fresco painting, and many of the most exquisite frescos from this period remain in stunning condition today.

Many Renaissance frescoes adorn the walls and ceilings of private, public, and religious buildings, often depicting biblical scenes or the stories of prominent saints.

The Renaissance period saw an explosion of experimentation with fresco techniques. Renaissance frescos tend to include lavish decorations and elements like gold leaf as seen in the Scrovegni Chapel by Giotto di Bondone in 1305. Many artists like Michelangelo and Raphael experimented with depth and perspective by carving into the wet intonaco plaster before painting.

In Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel Ceiling, he carved around the bodies of his nearly 300 figures from scripture, making them stand out from the background. Renaissance fresco painters also used shifts in linear perspective to alter the appearance of the space around the fresco. The Dominican Friary of San Marco (1438-1450) frescos by Fra Angelico is deeply contemplative and creates unique architectural effects by changing linear perspectives.

Towards the end of the Renaissance period, artists grew tired of the demanding techniques required for producing true buon frescos. Oil painting became the most popular medium and was used on wooden panels and stretched canvas.

An English Fresco Revival

Fresco painting techniques saw a revival during the 19th and 20th centuries in England. Public mural paintings became incredibly popular and the movement was spearheaded by those associated with the Arts and Crafts Movement, as well as the Pre-Raphaelite painters. Pioneers of the Arts and Crafts movement, like Phoebe Anna Traquair, harkened back to pre-industrial art forms.

A series of frescos by Traquair, known as Edinburgh’s Sistine Chapel, adorn the walls and ceiling of the Mansfield Place Church. William Brassey Hole painted a series of frescos at the National Portrait Gallery in Scotland. One of these frescos captures a Processional Frieze featuring famous Scottish figures, while another is devoted to St Columba, who brought Christianity to Scotland.

Fresco Painting Today

Fresco painting is certainly not as widespread today as it was in the past but some artists continue to celebrate and explore the medium. The Making of a Fresco, Showing the Building of a City (1931) is an iconic fresco by Diego Rivera, a famous Mexican artist, who was inspired by Marxist ideals. Rivera created a series of fresco murals around San Francisco Bay during the 1930s.

The fresco is a socialist commentary with different levels of society represented by artists on a complicated scaffold.

The frescos by Italian-American artist Francesco Clemente also mix traditional techniques with contemporary ideas. The Avo Ovo painted by Clemente in Madrid in 2005 weaves together the artist’s personal experiences and Neapolitan history.

Famous Frescos From Antiquity and Modernity

The long and culturally diverse history of fresco painting has left us with many beautiful frescos, each emblematic of its time. In the following section, we are going to look more closely at some of the most famous fresco paintings of all time. We begin with early frescos from Classical antiquity and Sri Lanka, and move onto some of the most famous frescos from the High Renaissance period.

Bull-Leaping Fresco (1600 – 1450 BCE)

| Artist Name | Unknown |

| Date | c. 1600 – 1450 BCE |

| Medium | Fresco |

| Dimensions (cm) | 78.2 × 104.5 |

| Where It Is Housed | Heraklion Archaeological Museum, Heraklion, Crete, Greece |

This fresco adorns the walls of the Knossos Palace in Crete. Despite the incredible age of this fresco, the colors remain vibrant and the composition complete. The fresco, painted some time around 1400 BCE, depicts heavily stylized Grecian figures leaping over a bull. Individual men would perform acrobatic tricks as they lept over the backs of cows and bulls in this unique Minoan bull-leaping ritual. This fresco is one of the most famous works of art from the ancient Minoan civilization and its condition is a testament to the durability of fresco painting techniques.

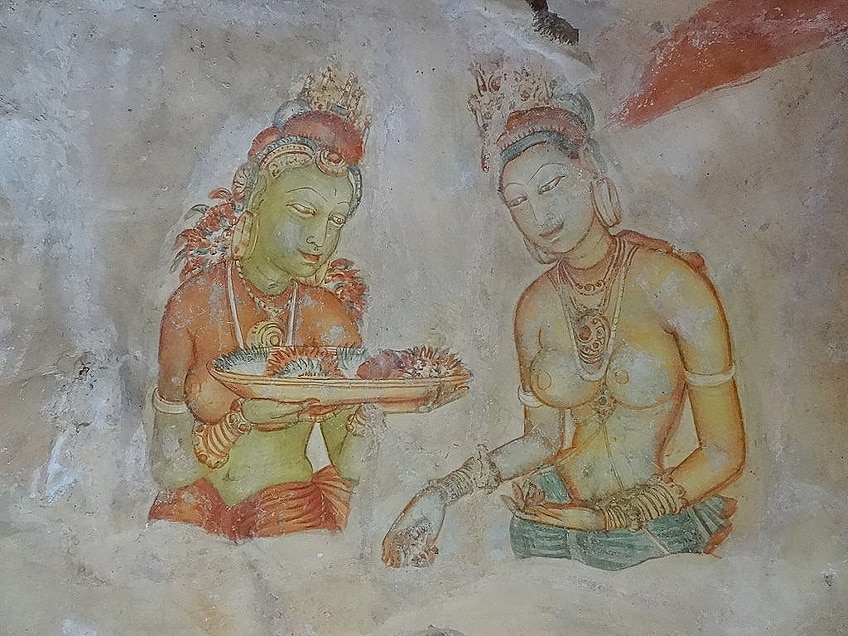

The Sigiriya Rock Frescos (500 – 400 BCE)

| Artist Name | Unknown |

| Date | c. 500 – 400 BCE |

| Medium | Fresco |

| Dimensions (cm) | 1400 x 400 |

| Where It Is Housed | Dambulla, Sigiriya, Sri Lanka |

The western side of the Sigiriya Rock in Sri Lanka is adorned with a fresco painted during the 5th century BCE. King Kasyapa commissioned this series of frescos to transform his palace into an ethereal kingdom. The frescos depict two stylized women holding bowls of flowers. There has been much debate about who these women were, with many believing them to be heavenly nymphs showering mortals and kings with celestial gifts. Others believe these women to be concubines and queens from the harem of King Kasyapa.

Whoever these women were, their beauty remains vibrant today and is protected from the weather by the rocky cave that encompasses them. This fresco sits around 100 meters above the ground in a small cave pocket. Whether they are celestial beings or not, these women have outlived the society that created them.

Sappho Fresco (55 – 79 CE)

| Artist Name | Unknown |

| Date | c. 55 – 79 CE |

| Medium | Fresco |

| Dimensions (cm) | 38 x 37 |

| Where It Is Housed | Naples National Archaeological Museum, Naples, Italy |

We have already spoken about the wealth of fresco murals discovered in Pompeii and this fresco painting, also known as Woman with Wax Tablets and Stylus is a beautifully preserved example. This fresco is a wonderful example of the durability of Roman buon fresco.

The “Sappho Fresco” survived a major volcanic eruption and remains in excellent condition for us to appreciate today.

The Sappho Fresco depicts a wealthy young woman dressed in luxurious robes, with gold thread in her hair and large gold earrings. The woman is holding a stylus to her lips and a stack of wax tablets in her other hand. Although named after Sappho, the wax tablets, which are associated with accounting, bear no connection to the Greek poet.

The Annunciation (1442 – 1443) by Fra Angelico

| Artist Name | Fra Angelico (1395 – 1455) |

| Date | 1442 – 1443 |

| Medium | Fresco |

| Dimensions (cm) | 230 x 321 |

| Where It Is Housed | Basilica di San Marco, Florence, Italy |

For many art historians, this fresco represents a transition from the Middle Ages to the art of the early Italian Renaissance. Painted by Italian artist Fra Angelico, The Annunciation has a more realistic composition than earlier Medieval paintings. Much of the Realism comes from the way that Angelico captured a sense of depth using a vanishing point.

A vanishing point is a perspective technique whereby the artist composed the piece along orthogonal lines that disappear at their meeting point.

This fresco is not the first exploration of this religious iconography by Angelico, as he created another fresco and three similarly composed panel paintings. This fresco, which resides in the San Marco Convent in Florence, is one of the most famous early Renaissance frescos.

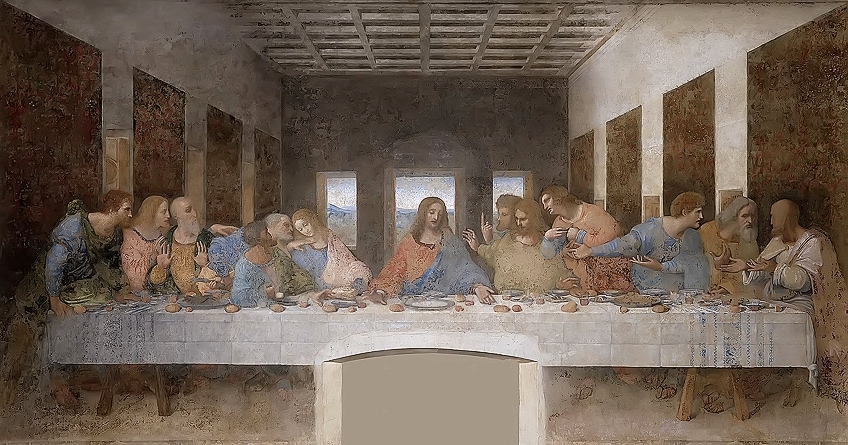

The Last Supper (1495 – 1496) by Leonardo da Vinci

| Artist Name | Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci (1452 – 1519) |

| Date | 1495 – 1496 |

| Medium | Fresco; tempera on gesso, pitch, and mastic |

| Dimensions (cm) | 460 × 880 |

| Where It Is Housed | Santa Maria delle Grazie, Milan, Italy |

This secco fresco is perhaps one of the most famous fresco paintings from the Italian Renaissance. The Convent of Santa Maria Delle Grazie commissioned Leonardo da Vinci to paint the famous biblical scene depicting Jesus’ final meal with his disciples. The spirit of exploration that characterizes Da Vinci as the ultimate Renaissance man is evident in this deviation from traditional buon fresco.

“The Last Supper” fresco is Da Vinci’s only surviving fresco and his largest painting that was created using a modified secco fresco technique.

Using a white lead undercoat applied on dry plaster, Da Vinci created the painting using tempera paint and oil glazes to increase the color vibrancy. The use of tempera paint also allowed Da Vinci to recreate the blending technique he was known for and make adjustments to the composition. Unfortunately, this experimental style was not well suited for plaster walls, and the fresco began to deteriorate during Da Vinci’s lifetime.

The beautiful fresco we see today has been restored several times and not all of these restorations have been completely successful. Despite the degradation and somewhat sketchy restoration process, there are several features of Da Vinci’s composition that make this painting one of his greatest works. The Last Supper uses a one-point perspective that Da Vinci created with orthogonal lines that extend towards the back of the painting.

The effect of this perspective is that the viewer sees the space within the fresco, as if it were a continuation of the viewer’s own space.

Leonardo da Vinci also created a light source on the left of the fresco that aligns with natural window light within the room. This lighting effect emphasizes the Realism of this fresco. Finally, Da Vinci included a realistic Humanism within this fresco by presenting the full range of emotional expressions on the disciples’ faces as Jesus declared that one of them would betray him.

“The Last Supper” fresco by Da Vinci is the first painting to place the figure of Judas among the other disciples at the table.

In earlier paintings, Judas was always depicted as separate from the other disciples, so the viewer could identify him as the traitor. Leonardo da Vinci places him firmly amongst the other disciples but he uses some clever compositional techniques to help the viewer easily spot Judas. For example, the figure of Judas is shaded darker than the disciples around him and draws attention to the symbolism behind light and darkness to highlight Judas’ moral character.

Sistine Chapel Ceiling (1508 – 1512) by Michelangelo Buonarroti

| Artist Name | Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni (1475 – 1564) |

| Date | 1508 – 1512 |

| Medium | Fresco |

| Dimensions (cm) | 3500 x 140 |

| Where It Is Housed | Sistine Chapel, Vatican Museums, Vatican City |

This enormous buon fresco by Michelangelo is undoubtedly one of the most famous frescos ever created. The colorful and complex fresco occupies the entire area of the Sistine Chapel ceiling. This buon fresco depicts nine essential biblical scenes and includes 343 separate figures. Michelangelo created a sense of depth in this fresco by scraping out sections of the wet intonaco around many of these figures.

Michelangelo is said to have been apprehensive at first when he was asked to complete this fresco because he saw himself primarily as a sculptor. Despite his doubts, he agreed to paint the ceiling of this Vatican chapel.

Not only was the scale of this fresco ambitious but the architectural features in the ceiling made this task all the more challenging.

Large-scale scaffolding was erected and Michelangelo and his assistants began the painting work. After a while, Michelangelo dismissed his assistants and finished the entire ceiling single-handedly. Michelangelo had to compensate for the distortion in his perspective created by the architecture and the curved ceiling. To do this, he devised an illusionary architectural structure in the center of the Sistine ceiling that framed the biblical scenes.

The School of Athens (1511) by Raphael

| Artist Name | Raffaello Sanzio da Urbino (1483 – 1520) |

| Date | 1511 |

| Medium | Fresco |

| Dimensions (cm) | 500 x 770 |

| Where It Is Housed | Apostolic Palace, Vatican City |

Our final famous fresco comes from the third great Renaissance painter Raphael. This series of monumental frescos takes inspiration from the four primary schools of thought: law, theology, philosophy, and poetry. The School of Athens is the fresco celebrating ancient Greek philosophers through portraits of Euclid, Plato, Socrates, and Aristotle. Raphael even included a sneaky self-portrait in this fresco.

If you visit the Vatican, you can find this fresco and the other three iconic works on the Apostolic Palace walls. The other three frescos include “Disputation of the Holy Sacrament”, “Triumph of Galatia”, and “Sistine Madonna”.

All four frescos were completed within five years between 1509 and 1514, which is an impressively short time frame for such large-scale works. Although Raphael was only in his late twenties when he received the commission for these frescos, he did so in competition with Michelangelo and Da Vinci.

Book Recommendations for Fresco Fanatics

What we have covered in this article is but a brief history of the fresco medium. If you are interested in delving deeper into the fascinating world of fresco paintings, we invite you to explore these top rated reads that provide an in-depth history of frescos in art history.

Italian Frescoes: High Renaissance and Mannerism 1510-1600 (2004) by

This hardcover book is the ultimate collection of 460 color-reproduced High Renaissance paintings and frescos, as well as 60 plans and illustrations in black and white. The authors, Michael Rohlmann and Julian Kliemann, cover frescos with religious significance and secular imagery. This book is one of five volumes on Italian frescos, with many readers praising the book’s high-quality images and informative texts.

For those looking for a guide on how to create technically astute frescos, look no further than this Kindle edition guide to fresco painting techniques. Authored by Olle Nordmark, this helpful book will help the modern and contemporary artist navigate their journey into fresco painting while learning about the history of the craft.

Florence: The Paintings & Frescoes, 1250-1743 (2015) by Ross King and Anja Grebe

If you want the most comprehensive book about the frescos and paintings created in Florence, then this hardcover illustrated book by Ross King and Anja Grebe will stand you in good stead. This book includes over 2,000 of the most beautiful artworks to emerge from Florence between 1250 and 1743. The paintings include every work displayed at the Uffizi Gallery, the Accademia, the Duomo, and the Pitti Palace.

Fresco painting techniques have been a fundamental feature of many cultural pieces of art throughout the ages. From the buon frescos of Classical Greek and Roman antiquity era to the vast frescos of the High Renaissance, the fresco medium has ensured that the culture and history of our human civilization have not been lost.

Take a look at our fresco art webstory here!

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is a Fresco Painting?

A fresco artwork refers to a painting that is created using pigment that is applied onto a surface with a freshly coated lime plaster. What shapes the foundation of a fresco painting is its process, which upon drying, fuses the earth pigments of the painting with the plaster to create a more durable artwork.

What Is the Difference Between a Fresco and a Painting?

There is one primary difference between a fresco artwork and a painting. While the two may overlap, a fresco is a type of painting that is created using specific processes that involve the application of pigments directly onto a wall surface that has been freshly plastered. A painting generally involves the application of paint onto any solid surface using tools such as paint brushes and sponges.

Is a Fresco the Same as a Mural?

Similar to the notion that frescos and paintings are somewhat alike, frescos and murals are alike in their definitions of painted artwork on a large wall surfaces. However, the difference lies in the process, which distinguishes a fresco from a mural. Frescos are created while the wall plaster is still wet or close to drying to enable the chemical fusion of pigment and plaster. Murals are usually created on dry surfaces and walls on a scale that is often large and employs paints such as household acrylic paint, spray paints, or outdoor paints.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Fresco Painting – The Age-Old Art of Applying Paint to Plaster.” Art in Context. February 17, 2021. URL: https://artincontext.org/fresco-painting/

Meyer, I. (2021, 17 February). Fresco Painting – The Age-Old Art of Applying Paint to Plaster. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/fresco-painting/

Meyer, Isabella. “Fresco Painting – The Age-Old Art of Applying Paint to Plaster.” Art in Context, February 17, 2021. https://artincontext.org/fresco-painting/.