WW2 Nose Art – The History of Decorating Warplanes

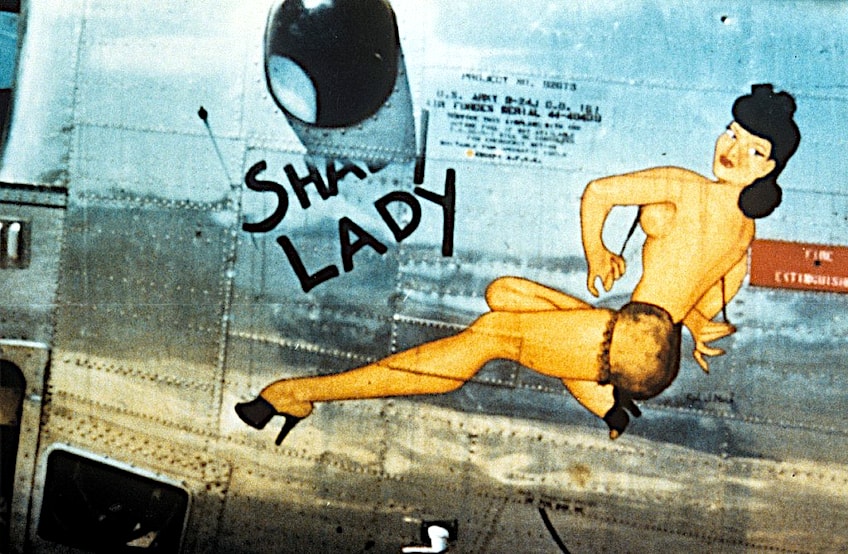

In WW2, nose art rose in prominence as plane art regulations were largely ignored. Pinup nose art, otherwise known as Bomber artwork, involved the painting of various designs on aircraft fuselages. This article will explore the history of WW2 nose art, and find out why plane art was important to the pilots.

The High-Flying Style of WW2 Nose Art

While the practice of Bomber artwork began for practical reasons such as identifying friendly units, it developed to convey the individual identity often restricted by combat uniformity, to bring back memories of their homes and peaceful times, and as a type of psychological defense against the stress and strain of war and the possibility of death. The appeal stemmed in part from the fact that pinup nose art was not officially allowed, even though the restrictions prohibiting it were not enforced.

It is often classified as a kind of folk art, due to its unique and unofficial nature. It’s also comparable to elegant graffiti. In both circumstances, the creator is frequently unidentified, and the work is transitory. Moreover, it is based on materials that are readily available. Although nose art is generally associated with the military, the Virgin Group’s commercial airliners incorporate “Virgin Girls” as part of its identity.

The tail art of numerous airlines, such as Alaska Airlines’ Eskimo, might be considered “nose art”, as could the tail marks of modern-day US Navy squadrons.

The History of Plane Art

Personalized decorations on combat aircraft were first utilized by German and Italian pilots. A sea monster drawn on an Italian flying boat in 1913 was the earliest known example of plane art.

The use of “boat” to describe an aircraft provides a clue as to the cultural origins of nose art: boats and ships were individually named, referred to as “she”, and large ships traditionally featured elaborately carved figureheads.

The introduction of painted decoration on aircraft was followed by the prevalent practice of putting a mouth underneath the propeller, which was started by German pilots during World War I. The shark-face insignia was subsequently made famous by the Flying Tigers, an American Volunteer Group, which first appeared in World War I on a German Roland C.II and British Sopwith Dolphin, but sometimes with a comical rather than terrifying appearance. Another well-known motif was the “prancing horse” of the Italian ace Francesco Baracca.

WW1 Nose Art

During World War I, bomber artwork was generally decorated with ornate squadron insignia. This was in accordance with the official policy issued by Brigadier General Benjamin Foulois, the Chief of the Air Service of the American Expeditionary Forces, on the 6th of May 1918, which required the construction of unique, easily recognized squadron insignia. The nose art of the time was sometimes created and executed by ground crew instead of pilots.

WW2 Nose Art

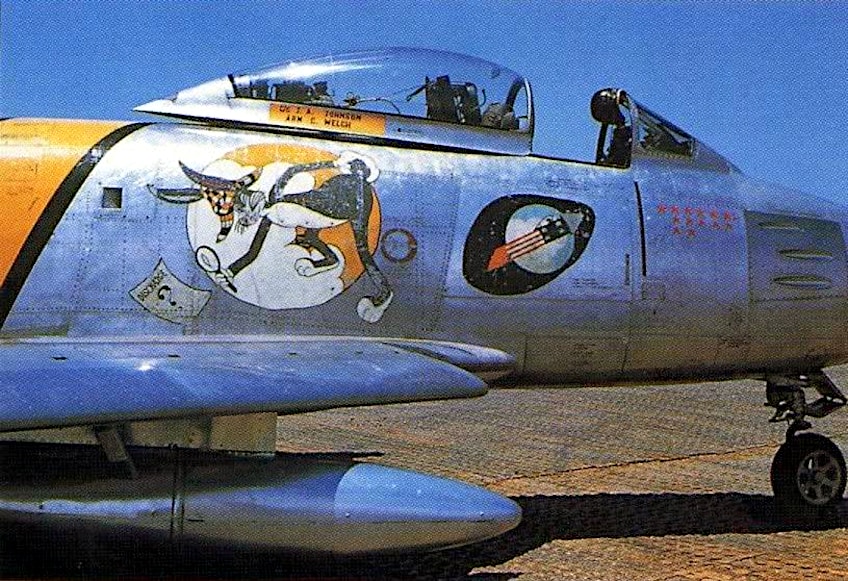

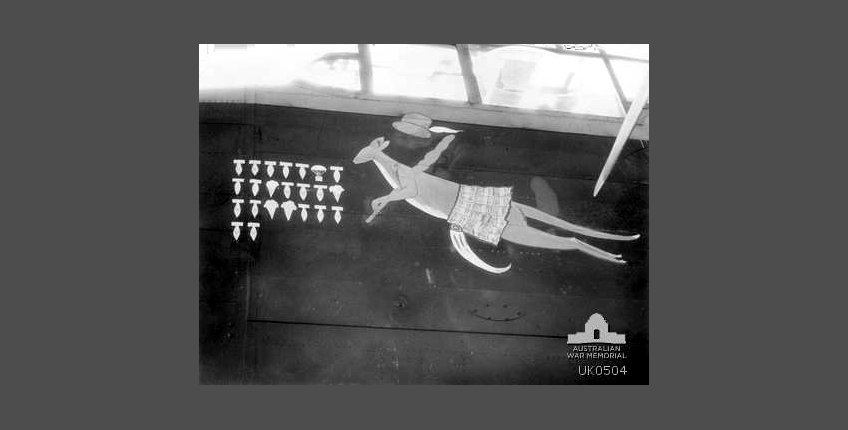

Genuine nose artwork first appeared during WW2, which many believe to be the genre’s greatest era, with both Allied and Axis pilots involved.

At the peak of the war, nose artists were in high demand in the USAAF and were well compensated for their efforts, while AAF leadership allowed nose art to bolster aircrew morale.

In contrast, the United States Navy restricted nose art, with most designs restricted to a few simply-lettered names, whereas nose art was rare in the Royal Canadian Air Force. The plane artwork was created by both experienced civilian artists and skilled amateur servicemen. The 39th Pursuit Squadron, for example, hired a Bell Aircraft artist to conceive and create the “Cobra in the Clouds” mark on its aircraft in 1941.

The shark-face design was possibly the most iconic nose art of WWII, initially appearing on the “76th Destroyer Wing” over Crete, when the twin-engined Messerschmitts outclassed the No. 112 Squadron RAF. The Commonwealth pilots were recalled to Egypt and replaced with Curtiss Tomahawks built on the same manufacturing line as the Flying Tigers being enlisted for duty in China. AVG pilots spotted a color image of a shark mouth decorated on a 112 Squadron P-40 fighter in North Africa in November 1941 and quickly borrowed the shark-face theme for their personal P-40Bs. The British variation was motivated by the shark mouth nose painting of the Messerschmitts. The pilots and ground personnel on the ground produced the art.

However, the Flying Tigers emblem – a winged Bengal Tiger leaping through a stylized “V” for Victory mark – was created by Walt Disney Company design artists.

Similarly, when the 39th Fighter Unit became the first American squadron in its theater to achieve 100 kills in 1943, the shark face was chosen for their Lockheed P-38s. The shark face is still employed today, most notably on Fairchild Thunderbolt IIs, particularly those of the 23rd Fighter Group. The greatest known piece of nose art ever displayed on a World War II-era American combat aircraft was known as The Dragon and His Tail, with Staff Sergeant Sarkis Bartigian as the artist.

The dragon artwork went along the full length of the fuselage’s side walls, with the dragon’s body represented right below and just aft of the cockpit, with the dragon clutching a naked lady in its forefeet. One of the earliest six groups that the Eighth Air Force deployed was the 91st Bomb Group and Tony Starcer served as the unit’s resident artist. Over a hundred pieces of notable B-17 nose art, including Memphis Belle, were painted by Starcer. The zodiac-themed nose artwork of the B-24 Liberator, located at RAF Sudbury, England, was created by a commercial artist called Brinkman from Chicago.

Recent research shows that bomber aircrew, who experienced high mortality rates during WWII, often formed close ties with the planes they flew and lovingly painted them with nose art. The flight crews also felt that the nose artwork brought good luck to the planes.

Post-WW2 Nose Art

Nose art was popular among groups of C-119 Flying Boxcar transports, flying A-26 Invader and B-29 bombers, and USAF fighter bombers during the Korean War. After the Korean War, the volume of nose art decreased due to adjustments in military rules and shifting attitudes regarding the portrayal of women. Names with matching nose art were frequently given to Lockheed AC-130 gunships during the Vietnam War. Examples include “Ghost Rider”, “Thor”, “War Lord”, and “The Arbitrator”.

The unofficial gunship insignia of a flying skeleton with a Minigun was also used on several aircraft until the war’s conclusion and was subsequently officially recognized. Nose art saw a comeback during the Gulf War and has been increasingly popular since the start of the Iraq War. Many crews are incorporating artwork into camouflage designs.

The reintroduction of the pinup nose art was informally sanctioned by the US Air Force, with the Strategic Air Command allowing nose art on its bomber force in the Command’s final years.

Regional Variations of Bomber Artwork

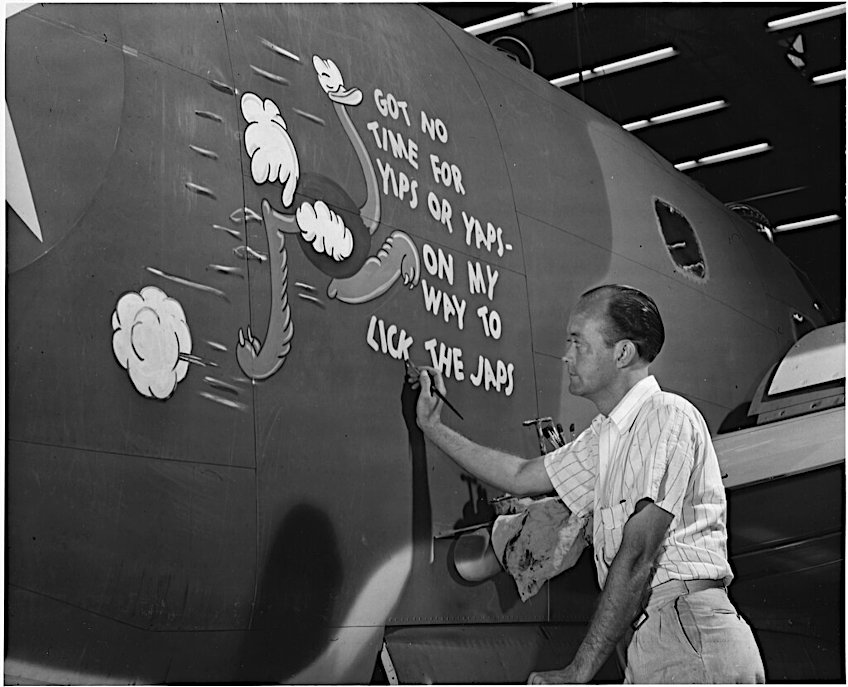

The inspiration for American nose art ranged from pinups like Betty Grable and Rita Hayworth to cartoon figures like Bugs Bunny, Donald Duck, and Popeye, as well as patriotic and mythical heroes. Lucky symbols like dice and playing cards, as well as references to death like the Grim Reaper, inspired nose art. The most popular works by American artists were pinups and cartoons, but other subjects included nicknames, animals, hometowns, and popular movie and song titles. Some nose art and phrases expressed hatred towards the enemy, particularly their commanders.

The greater distance the aircraft and personnel were from the public eye or headquarters, the more raunchy the pinup nose art tended to be. Nudity, for example, was more frequent in nose plane art on Pacific aircraft than on European aircraft. Nose art was not commonly seen on Luftwaffe aircraft, but there were exceptions. The Soviet Air Forces used historical imagery, legendary monsters, and patriotic slogans to paint its planes.

The Finnish Air Force’s attitude to the nose paint differed per unit. Some units outright prohibited bomber art, while others accepted it.

The nose painting on Finnish planes was inspired by similar nose art on American and British planes, and it was meant to improve morale and personalize the jets. During the Continuation War against the Soviet Union, nose painting became popular aboard Finnish fighter planes, and many specimens of the design have been preserved to this day. In general, Finnish air force plane art was amusing or satirical.

Because the Japanese military placed a heavy emphasis on uniformity and order and disapproved of individual expression, Japanese nose art was not as widespread as it was in other nations during World War II.

Some instances of Japanese nose art may be seen on airplanes employed by special forces or on aircraft owned by individual pilots. Traditional Japanese elements such as dragons, cherry blossoms, and samurai warriors were commonly used in the designs. The Japan Air Self-Defense Force painted Valkyrie-themed figures on fighter planes.

The Artist Responsible for Influencing Pinup Nose Art

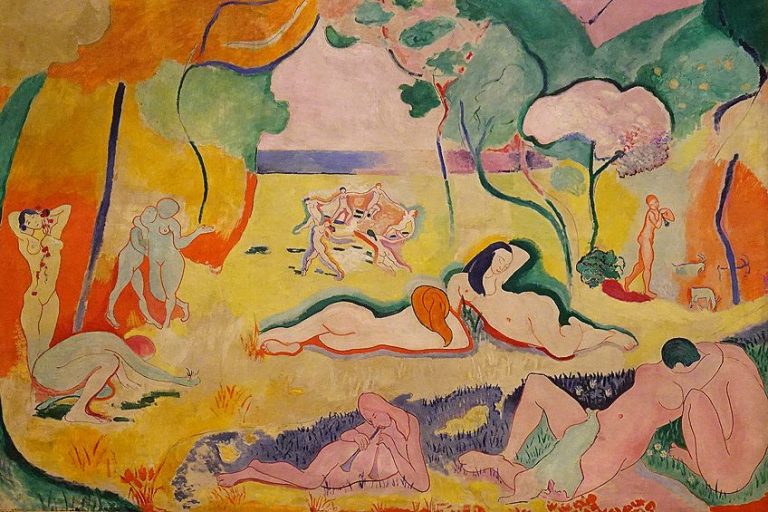

In the late 1930s, there were various photographers and illustrators who worked at an American magazine called Esquire that contained images and sketches of beautiful female bodies, defining the new image of women in its pages; nevertheless, the most notable of the time was George Petty.

Petty’s girls were usually accompanied by a humorous remark meant to catch the reader’s attention. These ladies’ popularity grew, and the space allotted for these images grew, while removing any form of distraction, and the girls became the full focus of attention on a white backdrop, where their bodies and expression were the main subject matter.

Petty’s Replacement

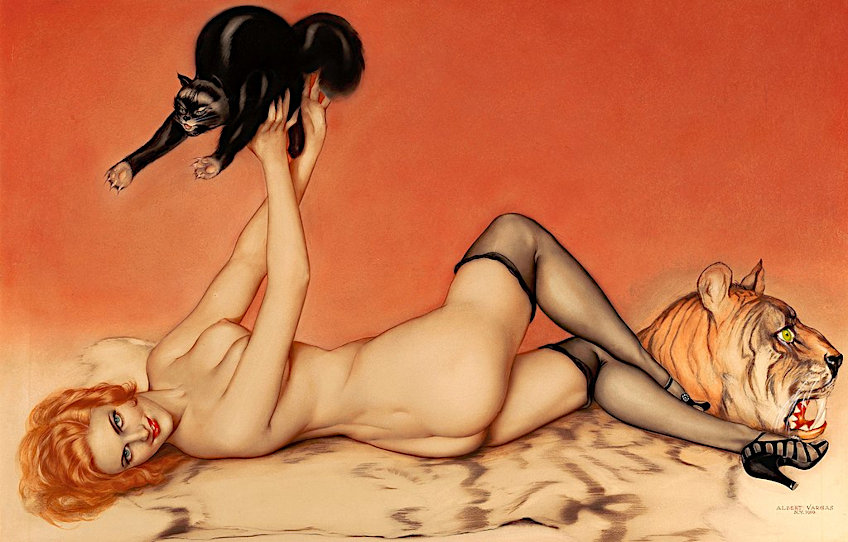

However, Petty’s pictures gained such prominence that he increased his financial demands on the publication. This spurred Esquire management to search for a substitute in 1940 that was on par with Petty’s images but cost less. Alberto Vargas, a Peruvian artist, was picked as a replacement.

Vargas was born in Arequipa in 1896, the son of a well-known photographer, which meant he grew up surrounded by photographs, cameras, and the aesthetic milieu of photography, as well as learning how to use the airbrush.

Soon after, he developed a passion for sketching and traveled with his family to Europe, where he trained as an artist in Zurich and Paris, while expanding his knowledge of classical painting, particularly that of Ingres.

Later that year, in 1916, he relocated to New York, where he launched his creative career painting theatrical actresses with a distinct blend of grace and femme fatale. Vargas consequently developed the image of a sensual, social, and stylish female who would emerge as the new goddess of the 20th century, representing the country’s educated and autonomous woman. During the 1930s, Vargas worked for a number of Hollywood studios, creating portraits and film posters, until he was chosen by Esquire in 1940 to replace Petty.

Vargas’ first illustrations debuted in October 1940, under the pressure to imitate his predecessor’s style; yet, Vargas quickly imposed his own style.

The Vargas Girls

Because of his enormous popularity, Esquire published the first Vargas calendar in December 1940, which included a female in each month and was a financial success. Vargas girls immediately became associated with American women’s feminine sensuality, refinement, and beauty. Vargas women offered a more believable female beauty model than prior depictions. With the United States’ entry into World War II in December 1941, women would reclaim a significant position in society, and transformations in women’s sexuality would commence, with the Vargas girls serving as a reference symbol for women – women’s values were changing.

With the outbreak of the war, Vargas’ girls became not merely icons of feminine beauty, but also patriotic icons of the American woman. As a result, between 1942 and 1945, his works typically related to war featured military aspects or depicted women from various branches of the armed services. It is worth noting Vargas’s work’s appeal among soldiers serving abroad, who instantly felt a deep connection with the woman he represented to them.

These girls quickly shared barracks, lockers, trenches, and even vehicles with photos of family and friends.

Because of the high demand from soldiers, Esquire produced more than nine million copies between 1942 and 1946, which were transported globally and given to soldiers at the bases where the soldiers were stationed in order to boost morale.

The Rise in Popularity of the Artwork

Additionally, the calendars were extensively distributed with the magazine, with Esquire starting to include a higher number of girls in its military editions. The practice of depicting the Vargas girls on bomber planes rapidly gained popularity, as they served as a protective talisman for their pilots, reminding them of their country and why they served. Inspired by Vargas’ artwork, the troops emblazoned them on their planes as a sign of good luck or as a type of goddess of battle, but they also had a functional purpose by distracting opposing pilots during air combat.

When the men came home and resumed their employment at the end of the war, many women were forced to relinquish some of the freedoms they had obtained during the war in order to resume their conventional roles. As a result of the war, there would be a significant increase in marriage and birth, resulting in an ideal American woman centered on a happy and reliant housewife – but the image of the ideal woman characterized by her naivety would also be retained, but not open sexuality.

Marriage and motherhood were best viewed in a setting of societal constraint that attempted to leave the liberal practices of war behind. It’s hardly surprising, then, that such images were left in the past in this highly conservative atmosphere.

Where to See Plane Art Today

Many specimens of WWII nose art have been preserved and may be seen in institutions and museums all over the world. In the United States, the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C. has a substantial collection of World War II nose art, including numerous examples from the legendary Flying Tigers fighter squadron.

The Museum of the United States Air Force in Ohio also has a huge collection of nose art, as well as other wartime relics and memorabilia.

Several other aviation museums around the country, including the National Museum of World War II Aviation in Colorado, and Pima Air and Space Museum in Tucson, Arizona, have examples of nose art on exhibit.

Many military aviation museums in Europe, including the Imperial War Museum in Duxford, the Royal Air Force Museum in London, and the Musée de l’Air et de l’Espace in Paris, have instances of nose art on exhibit. Nose art may also be found on repaired and functioning planes which are maintained by various groups throughout the world that provide flights and trips. It is important to take into account that nose art is a type of transitory art, and original works are difficult to discover; most surviving specimens are replicas or were copied to other surfaces, such as canvases.

Similar to how ships used to feature names and elaborately carved figureheads, or a person might customize a car, nose art arose from the need of the crew members to identify with their aircraft. European armies began decorating their planes with fearsome animals, family crests, and other emblems during World War I. When the American forces arrived, they swiftly followed the Europeans’ lead and adorned their own planes, as well as identifying them with the newly mandated unit insignia. During WWII, nose painting was particularly popular as a way to differentiate planes, create a group identity, and connect personnel to aircraft.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is Plane Nose Art?

The front part of a plane is referred to as the nose, and pilots and crew would often adorn these spaces with artworks. Themes for nose painting ranged from the famous pin-up model to mascots, lucky symbols, triumph scenes, and landscapes. While the use of the female form became legendary, portraying women as objects is now considered insulting, as are stereotypical portrayals of other groups. Even during WWII, military laws barred more raunchy works, but with soldiers all over the world, regulations like these were difficult to implement and were frequently ignored in favor of morale boosting. To get around the regulations, several teams painted their drawings with water-soluble paints, anticipating that the following rainstorm would wash away their mischief.

Do People Still Make Nose Art?

Yes, nose art is still produced today. Despite the fact that plane art has been there since World War I, it remains a popular form of expression among aviation fans and pilots. Some current examples of nose art may be seen on military and privately owned aircrafts.

What Influenced Nose Art?

American bomber crews pioneered the technique in Africa and Europe, which was quickly adopted by fighter pilots and expanded to other allied countries. The artwork was often created by the pilots or by local artists, and it frequently included patriotic, comical, or pin-up themes. The purpose of nose painting was to enhance morale and personalize the planes, and it immediately became a fashionable form of self-expression among aircrews. Furthermore, nose art was influenced by contemporary entertainment and media such as comics, movies, and pin-up posters, which gave inspiration for many of the motifs and themes utilized in nose art.

What Influence Did Nose Art Have on the Enemy?

The purpose of nose plane painting was to personalize and embellish aircraft rather than to have an influence on the opponent. Certain nose art designs may have frightened some enemy pilots, especially if they were intimidating or reflected the victories of a certain unit. Furthermore, nose art could potentially also be utilized for propaganda purposes, as it could be used to transmit certain ideas or beliefs. Essentially, it’s more of a means of self-expression and self-preservation than an actual tactical measure.

What Influence Did the Work of Alberto Vargas Have on Nose Art?

Many of the pilots and flight crews that used nose art on their planes were known to be lovers of Alberto Vargas’ art, and his pin-up beauties were among the most-often replicated pictures in nose artwork. Vargas’ influence may be observed in the many nose artworks that depict highly-glamorized ladies in provocative poses. Alberto Vargas was an artist and illustrator from Peru. His pin-up work portrayed voluptuous ladies and was a key inspiration for many of the pictures and themes utilized in nose art. Alberto Vargas’ pin-up work was extensively spread through posters, periodicals, and calendars during the war, and the style became a popular form of self-expression.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “WW2 Nose Art – The History of Decorating Warplanes.” Art in Context. September 13, 2023. URL: https://artincontext.org/ww2-nose-art/

Meyer, I. (2023, 13 September). WW2 Nose Art – The History of Decorating Warplanes. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/ww2-nose-art/

Meyer, Isabella. “WW2 Nose Art – The History of Decorating Warplanes.” Art in Context, September 13, 2023. https://artincontext.org/ww2-nose-art/.