Appropriation in Art – Why Artists Use Existing Elements

Appropriation Art refers to the utilization of pre-existing objects or imagery with almost no alteration. The practice of appropriation in art has served an important role throughout its history. In regards to the visual arts, artistic appropriation refers to the correct adoption, borrowing, recycling, or sampling of human-made cultural imagery.

What Is Art Appropriation?

The premise is that the current piece recontextualizes whatever it borrows imagery from, and this makes the creation fresh – which is a fundamental aspect to grasp in our comprehension of appropriation photography and art. In most circumstances, the original “object” remains available in its original form.

Artistic appropriation, like found object art, is defined as “the purposeful copying, borrowing, and altering of previous imagery, objects, and concepts as an aesthetic method.”

Appropriation art has also been characterized as “the incorporation of a physical entity or perhaps an extant artwork into a new work of art.” Appropriation in art highlights issues of uniqueness, legitimacy, and ownership, and is part of the lengthy modernist heritage of art that calls into question the essence or meaning of art itself.

The History of Appropriation in Art

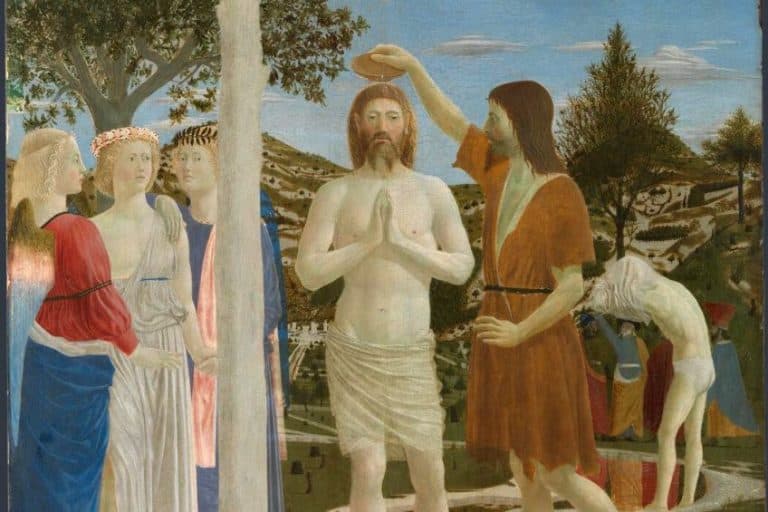

Many painters in the 19th century made allusions to past artists’ pieces or topics. For instance, Jean-Auguste Dominique Ingres produced Madame Moitessier’s portrait in 1856. The unusual posture was influenced by the renowned antique Roman artwork Herakles Finding His Son Telephas (early 2nd century BCE).

As a result, the creator established a connection for both his subject as well as the Olympian goddess. Similarly, Vincent van Gogh can be identified by instances of works influenced by Delacroix, Jean Francois Millet, or Japanese images in his personal possession.

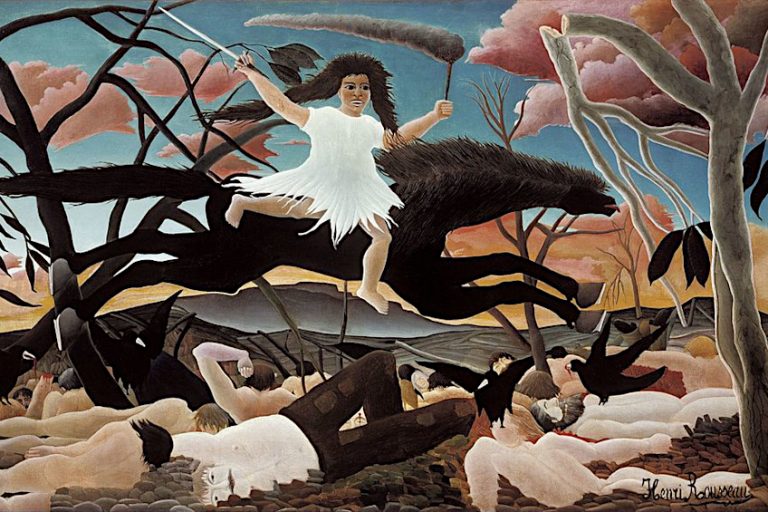

However, appropriation art as an art form may be traced back to Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso’s cubist assemblages and collages from 1912 onward, in which genuine things such as newsprint were used to symbolize themselves.

Early 20th Century

Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso incorporated artifacts from non-art environments into their works in the early years of the 20th century. Picasso placed a strip of oilcloth onto the painting in 1912. Following pieces, such as Guitar, Newspaper, Glass, and Bottle (1913), in which the artist utilized news clippings to build shapes, are examples of early assemblage that became associated with synthetic cubism. The two painters included elements of the “actual world” into their paintings, provoking debate over the perceived significance and artistic expression.

In 1915, Marcel Duchamp proposed the readymade notion, in which “commercially created functional items achieve the stature of art only through the processes of choice and display.”

Duchamp first probed this idea in 1913, when he attached a seat with a bike wheel, and again in 1915, when he bought a snow spade and wrote it “in anticipation of the broken arm, Marcel Duchamp.” Under the alias R. Mutt, Duchamp coordinated the entry of a readymade to the Society of Independent Artists exposition in 1917. It was dubbed Fountain and consisted of a men’s urinal made from porcelain perched upon a platform.

The piece was dismissed by the show committee because it presented a clear challenge to established conceptions of high art, authorship, uniqueness, and imitation. However, other art critics had strong views surrounding the work.

They remarked that “It makes little difference whether Mr. Mutt built the fountain with his own hands or not. He PICKED it. He took an everyday item of life, rearranged it so that its usefulness vanished under the new name and viewpoint, then invented a new notion for that piece.”

The Dada group continues to experiment with appropriating common materials and combining them in collage. Dada pieces exhibited purposeful absurdity and a disregard of art’s established norms. Kurt Schwitters‘ “merz” pieces have a comparable sensibility. Parts of them were built from found things, and they took the shape of enormous structures known as installations.

Following the Dada movement, the Surrealists adopted the use of ‘found items,’ such as Lobster Telephone (1936) by Salvador Dali. When these recovered artifacts were joined with other unusual and scary objects, they took on new significance.

Realism and Pop Art (1950 – 1960)

Robert Rauschenberg employed what he called “combines” in the 1950s, merging ready-made materials like tires or mattresses with paint, silkscreens, collages, and photography. Likewise, Jasper Johns, who worked with Rauschenberg during that period, integrated found artifacts into his art.

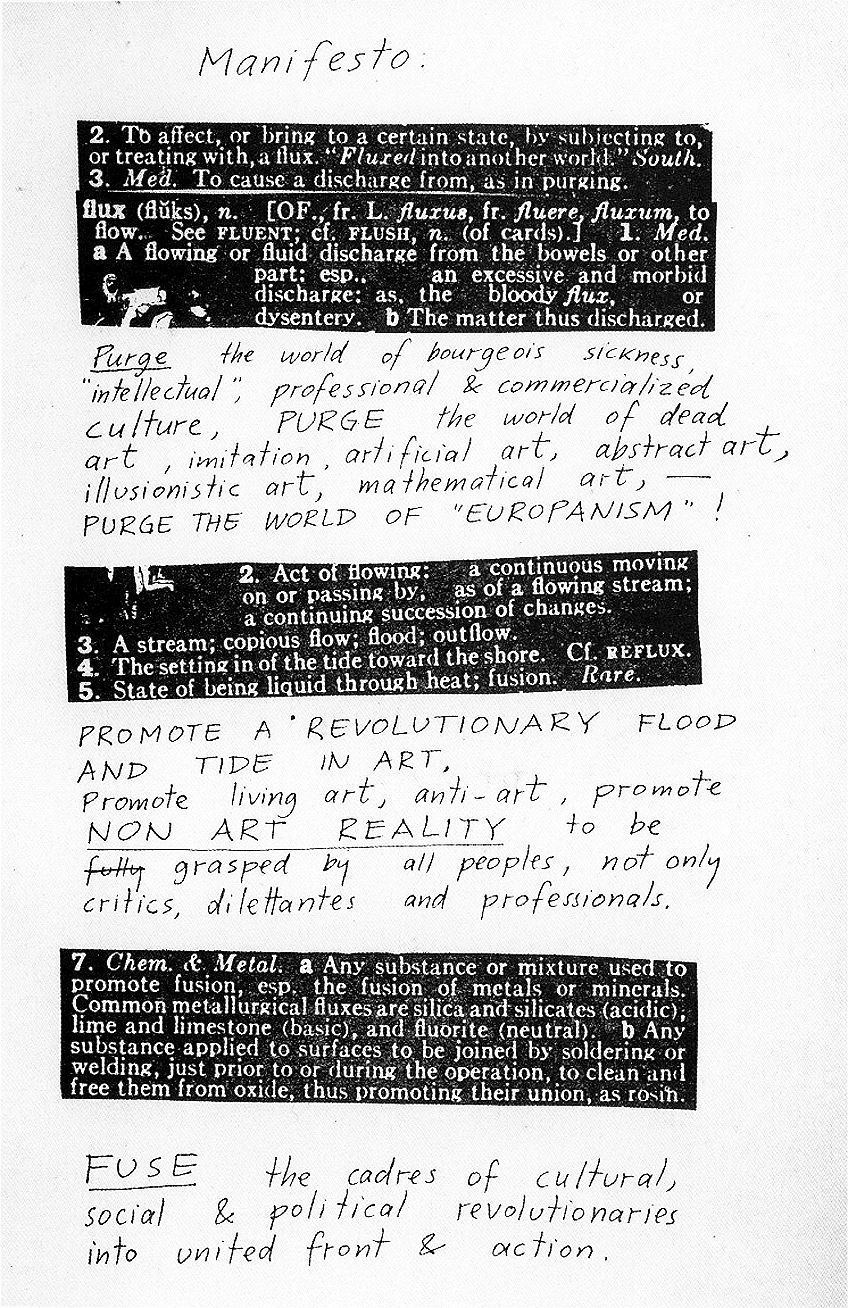

The Fluxus art movement made use of artistic appropriation as well, as its members combined many artistic fields such as the visual arts, music, and writing.

They conducted “action” gatherings and created sculptural pieces using unorthodox materials during the 1960s and 1970s. Artists like Andy Warhol and Claes Oldenburg copied motifs from corporate design and public culture, as well as methods from these sectors, in the early 1960s, with Warhol, for instance, painting Coca-Cola bottles.

They were dubbed “pop artists” because they considered mass popular culture as the primary vernacular language shared by everybody, regardless of education.

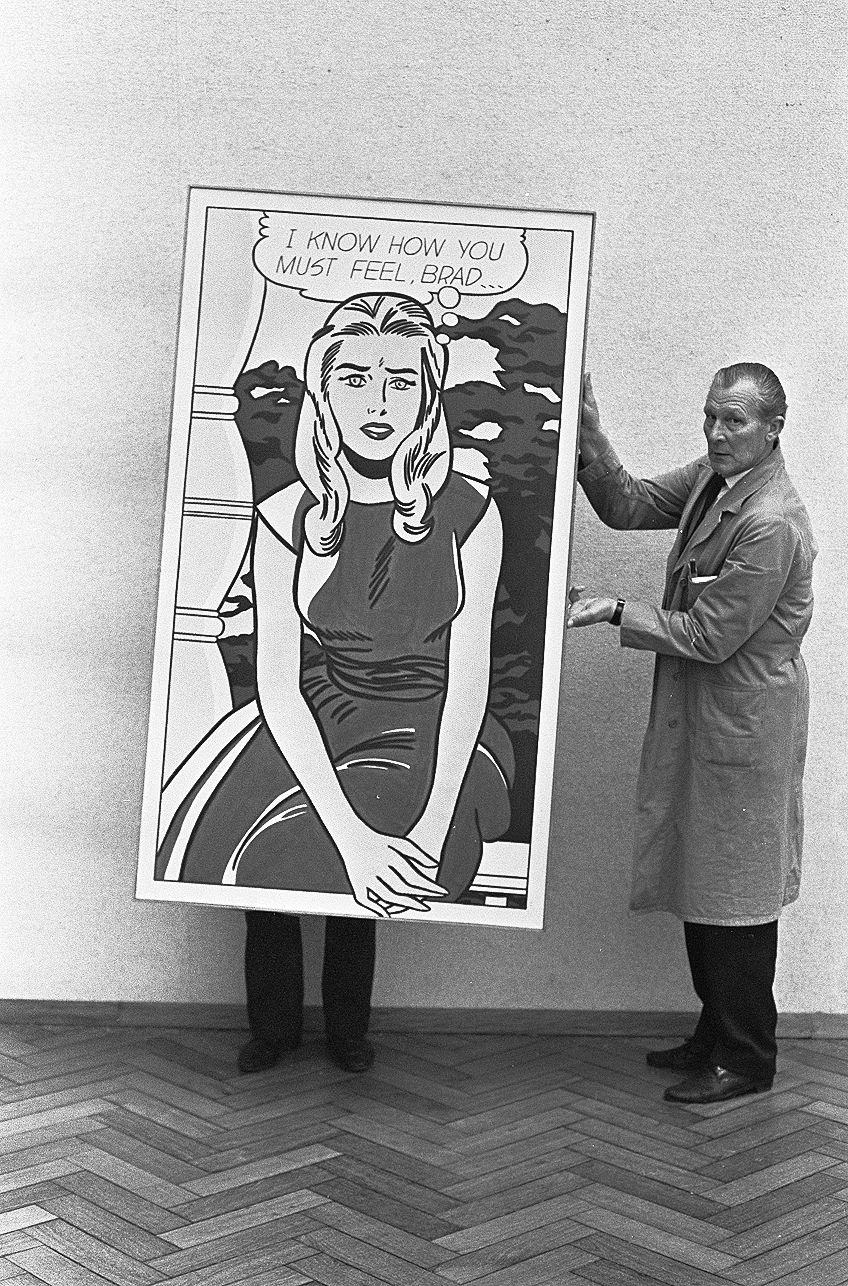

These creators were completely immersed in the detritus created by this mass-made culture, embracing disposableness and detaching themselves from the traces of an artist’s presence. Roy Lichtenstein, one of the most well-known pop painters, became notorious for copying images from comic books in works such as Drowning Girl (1963).

Elaine Sturtevant recreated great masterpieces by her peers. Among the artists she ‘copied’ were Jasper Johns, Andy Warhol, Joseph Beuys, James Rosenquist, Marcel Duchamp, Roy Lichtenstein, and others. While she did not primarily reproduce Pop Art, it was a key part of her profession. In 1965, she recreated Andy Warhol’s Flowers. She was instructed to replicate the creator’s own approach, to the point that when Warhol was constantly questioned about it, he once replied, “I don’t know. I’m not sure. Inquire with Elaine.”

In postwar Germany, German painters Sigmar Polke and his companion Gerhard Richter developed “Capitalist Realism,” offering a satirical criticism of consumerism. They utilized previously taken images and altered them. Polke’s most well-known works were composites of pop culture and commercial images, such as his Supermarkets scenario of superheroes browsing at a supermarket.

Neo-Pop and the Pictures Generation (1970 – 1980)

Whereas in previous times, appropriation in art was represented by ‘language,’ today’s appropriation art has been symbolized through photography as a method of ‘semiotic forms of representation.’ The Pictures Generation was a collection of creators that used appropriation and collage to highlight the artificial character of pictures, and were inspired by Pop art.

Sherrie Levine tackled the practice of appropriation as an artistic issue.

Levine frequently quotes complete compositions in her art, such as Walker Evans’ photos. Levine engages with the concept of “nearly same,” questioning ideas of uniqueness and calling attention to the relationships between authority, sexism, innovation, commercialization and market value, the social origins and purposes of art. Richard Prince re-photographed advertising for Marlboro smokes in the 1970s and 1980s. His work enhances the significance of faceless and omnipresent cigarette advertising promotions and focuses our attention on the pictures.

Appropriation artists make observations on many parts of society and culture.

To interact with philosophical and cognitive theory, Joseph Kosuth appropriated pictures. Richard Pettibone started reproducing pieces by newly recognized painters such as Andy Warhol, and subsequent modernist icons, on a tiny scale, marking the actual artist’s name and also his own.

Jeff Koons rose to prominence in the 1980s by producing conceptual sculptures, such as The New Series.

This was a sequence of vacuum cleaners, typically chosen for trade names that resonated with the artist, such as the legendary Hoover, and in the manner of Duchamp’s readymades. Later, he made stainless steel artworks that were influenced by inflatable toys like rabbits and dogs.

The 1990s

Artists continued to make appropriation art throughout the 1990s, utilizing it as a vehicle to confront theoretical and societal concerns rather than focusing on the pieces themselves. Damian Loeb used film and cinematography to speak on topics of realism and simulacrum.

Deborah Kass, Christian Marclay, and Genco Gulan were among the other well-known painters that were active during this period of appropriation.

Sherrie Levine borrowed the idea from Duchamp’s Fountain (1917) when she created polished cast bronze urinals. They are seen as a “homage to Marcel Duchamp’s well-known readymade. Contributing to Duchamp’s audacity, Levine elevates his gesture’s materialism and polish, transforming it again into an “art object.” As a feminist designer, Levine reimagines works by male painters who seized patriarchal control in art history.”

21st Century

Appropriation is widely employed by current artists who regularly recreate prior artworks, such as French artist Zevs, who reworked logos of businesses such as Google or David Hockney’s works. Many metro and street painters, such as Banksy or Shepard Fairey, employ imagery from mainstream cultures, such as Banksy’s Girl with a Pierced Eardrum, which stole artworks by Vermeer or Claude Monet.

Richard Prince published a series of appropriation photography works named New Portraits in 2014, stealing pictures of nameless and famous people who had uploaded a selfie on Instagram. The artist’s changes to the photographs are the remarks Prince placed under the photos.

Mr. Brainwash is a street artist who rose to prominence as a result of Banksy, and whose work mixes historic pop images with present cultural iconography to produce his rendition of the pop–graffiti art fusion favored by other street artists.

Art Appropriation in the Digital Age

Since the 1990s, the appropriation of historical predecessors has been as diverse as the notion of appropriation itself. A never-before-seen quantity of appropriations permeates not only the visual arts but all cultural fields. The younger breed of appropriators sees themselves as “archeologists of the moment.” Some people refer to “post-production,” which is the re-editing of “the script of culture” based on pre-existing compositions.

The acquisition of other people’s works or existing cultural items is usually guided by the idea of utility. So-called “prosumers” – people who consume and produce at the same time – trawl through the digital world’s omnipresent library, sampling the ever-accessible pictures, phrases, and sounds to ‘remix’ them as they please. Appropriations have now become a common occurrence.

The new “remix generation,” which has taken over not just the visual arts, but also music, books, dance, and cinema, has sparked heated arguments. Lawrence Lessig, a media researcher, invented the phrase “remix culture” in the early 2000s.

On the one hand, many anticipate a new era of inventive, helpful, and enjoyable methods for art in the digital and globalized twenty-first century. The new appropriators will not only recognize Joseph Beuys’ statement that everybody is an artist, but they will also “create free societies.” By ultimately freeing art from conventional conceptions like aura, uniqueness, and brilliance, they will pave the way for new ways of interpreting and describing art.

Critical observers view this as the beginning of a massive issue. If creativity is based only on careless procedures of discovering, copying, recombining, and modifying pre-existing material, concepts, forms, names, and so on from any source, art will be viewed as a marginalized, low-demanding, and backward activity in their eyes.

Because art is limited to allusions to pre-existing notions and forms, they anticipate an infinite stream of recompiled and recycled goods. Skeptics see this as a recycling society with a fixation with the past. Some argue that only idle individuals with nothing to say allow themselves to be inspired by history in this way. Others are concerned that this new tendency of appropriation is motivated solely by a desire to adorn oneself with an appealing ancestry.

Appropriation in art is characterized as a type of “racing halt,” alluding to the acceleration of unpredictable, uncontrollable actions in highly mobilized, dynamic Western societies ruled more by abstracted methods of authority.

Unfettered access to the digital repository of creative works and easily accessible digital technologies, as well as the prioritization of new creativity and new procedures over an ideal masterwork, gives rise to an excitable busyness around the past rather than introducing new excursions into uncharted territory. These could bring to light the neglected specters and overlooked ghosts of our popular myths and philosophies.

Examples of Appropriation in Art

Andy Warhol was hit with a slew of cases from photographers whose artwork he stole and then turned into silkscreens. Despite being blatantly stolen, Warhol’s iconic Campbell’s Soup Cans are widely deemed to be non-infringing. Jeff Koons has even been sued before; one such time, the designer was charged after appropriating an image made by Art Rogers of two individuals cradling a litter of puppies. Let’s take a look at some famous examples of appropriation in art.

Fountain (1917) by Marcel Duchamp

| Date Completed | 1917 |

| Medium | Glazed Ceramic |

| Dimensions | 61 cm x 36 cm x 48 cm |

| Current Location | 291 Art Gallery |

A regular item of plumbing selected by Duchamp was entered for an installation of the Society of Independent Artists in April 1917, the Society’s debut exhibition. Duchamp described his Readymade sculptures as “common things elevated to the grandeur of a piece of artwork by the designer’s action of selection.” The urinal’s orientation was changed from its regular position in Duchamp’s exhibition.

Fountain was not denied by the committee since Society regulations indicated that all works submitted by artists who paid the money would be admitted, but the sculpture was never displayed.

The work is perceived as a significant landmark in twentieth-century art by art historians and avant-garde theorists. In the 1950s and 1960s, 16 reproductions were requested from Duchamp and created with his agreement.

Some argue that the original piece was created by the woman artist Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, who presented it to Duchamp as a friend, while art historians argue that Duchamp was entirely responsible for Fountain’s exhibition.

The influence of Duchamp’s artwork altered people’s perceptions of art because of his emphasis on “intellectual art” rather than merely “ocular art,” as this was a way to involve prospective viewers in a thought-provoking manner rather than rewarding the aesthetic established order of “turning from traditionalism to modernity.” Because Stieglitz’s photograph is the unique image of the initial sculpture, certain interpretations of Fountain are based on looking not just at copies but also at this specific shot.

Campbell’s Soup Cans (1968) by Andy Warhol

| Date Completed | 1968 |

| Medium | Screenprint |

| Dimensions | 81 cm x 48 cm |

| Current Location | Museum of Modern Art |

Campbell’s Soup Cans are among the most famous images in American contemporary art. The soup cans, which began as a series of paintings in 1962, received international recognition as a landmark in Pop Art. When the artworks were originally shown that year, they were presented together as if they were items at a grocery shop. Each soup can was represented a different taste and was modeled after the white and red soup cans.

Though they seemed to be similar to well-known supermarket goods, the artist’s workmanship could be seen in the tiny changes in the text and hand-stamped insignia on the base of each container.

The series is made even more fascinating by the contrast of pure copy and the artist’s hand. The series’ inspiration came from Warhol’s private life. “I used to consume it,” he says. “I had the same meal every day for maybe 20 years, the very same dish over and over again.”

This notion of recurrence was undoubtedly absorbed by the artist, as well as expressed by commercialized mass culture. The appearance of Campbell’s Soup Cans was heavily questioned at first, as many spectators struggled to reconcile such blatant exploitation of a mundane commodity.

However, in 1968, Warhol expanded on the ideas of repetition and production by making two presentations of Campbell’s Soup Can screenprints.

After Walker Evans (1981) by Sherrie Levine

| Date Completed | 1981 |

| Medium | Gelatin Silver Print |

| Dimensions | 12 cm x 10 cm |

| Current Location | Metro Museum of Art |

Levine unapologetically rephotographed Walker Evans’ shot of Allie Mae Burroughs, spouse of an Alabama subsistence farmer, over fifty years after Evans took it. Notably, she did not capture the actual print itself, but rather a replica of the image in a Walker Evans show booklet. The image after Walker Evans: 4 is a copy of a replica of the actual photo.

Even this characterization is a little deceptive because there is no singular “original” Evans image – many prints, all identical, exist. Levine exposes the ambiguities of authenticity and genuineness inherent in the medium by rephotographing Evans’ photograph.

She also challenges how the artistic, or aesthetic, worth of a work of art is entwined with concepts of artistic genius, and how that worth is then commercialized in the art market, depending on exclusivity and scarcity.

Levine’s conceptual effort praised as a characteristic of postmodern art is reminiscent of French philosopher Roland Barthes’ article “The Death of the Author,” in which he contended that it was the reader’s responsibility, not the author’s, to produce and decide to mean. Levine used Barthes’ words when she said, “The meaning of a picture rests not in its beginning, but in its destiny.” “The creation of the spectator must come at the expense of the painter.”

By putting so much power in the hands of the viewer, that is, by asking the audience to challenge and perceive, Levine brings into discussion the romantic ideas of the “prodigy” artist who provides authentic actuality, but instead indicates a circumstance in which visuals are never authentic and are always derived from numerous sources that must be decoded by the audience.

Arranged by Barbara and Eugene Schwartz (1982) by Louise Lawler

| Date Completed | 1982 |

| Medium | Gelatin Silver Print |

| Dimensions | 32 cm x 55 cm |

| Current Location | Private Collection |

This image is part of one of Lawler’s initial displayed series of images chronicling residential and institutional art exhibitions. We can see two of Cindy Sherman’s artworks hanging in a room viewable through the open door, as well as an abstract scene, mounted on the wall next to the entry, with the picture centered on a doorway that goes between rooms.

Lawler does not name each work; instead, collectors Barbara and Eugene Schwartz are credited with arranging the work, which is highlighted in the title as active makers of the scene on exhibit.

The artist makes visible the continuous reception of artwork by moving the viewer’s emphasis from the creator to the collector, offering this exhibition to the audience in a way that places the artwork in the context of both its trade worth and its cultural standing.

They no longer belong to their creator, but rather serve as a reflection of their owner’s likes and personality.

Although this act of depicting works of art as they are presented in collectors’ houses is preoccupied with the ways in which acquiring and arranging modify the significance of artworks, Lawler’s stance on this remains ambiguous. She avoids simple condemnation of how artworks are commercialized through the market, instead of focusing on the topic without intending to clarify it.

We Don’t Need Another Hero (1986) by Barbara Kruger

| Date Completed | 1986 |

| Medium | Photographic Silkscreen |

| Dimensions | 277 cm x 533 cm |

| Current Location | Various Billboards |

The picture and words associated with Barbara Kruger’s work have a figurative connotation as they connect to one of J. Howard Miller’s 1942 posters titled Rosie the Riveter. During World War II, the Rosie the Riveter image was produced to encourage women to enter the labor sector. Kruger exploits the environment in which the Rosie the Riveter billboard was created to enhance the significance of her work.

Kruger’s work is based on the assumption that the audience would recognize the relationship between how females were perceived before the war and how females are perceived after the war in order to comprehend her work.

Nevertheless, postmodernism implies that, while a postmodern creation may be a “criticism of the source,” it is “not to revert to them.” Thus, Barbara Kruger’s art might be read as another hero is not required because the battle is gone and will not be returning.

As a result, Kruger’s work is intertextual but not self-determined, as it acknowledges the past to develop consciousness in the present.

Hymn (1999) by Damien Hirst

| Date Completed | 1999 |

| Medium | Bronze |

| Dimensions | 6m |

| Current Location | Gagosian Gallery |

In 2000, Damien Hirst was compelled to pay an unknown compensation to the creators of a toy that he had pirated, culminating in a large sculpture that looked remarkably similar to the original. Hirst’s method is known as appropriation, but what exactly does it imply, and is it theft or innovation?

Hirst enlarged the toy to a six-meter-tall sculpture and altered the components from plastics to gold, bronze, and silver.

Hirst has also changed the environment of the artwork from a medical toy to a modern art museum. His little modification to the source toy design culminated in a court lawsuit charging him for plagiarism. Hirst was convicted and sentenced to make restitution for his appropriation.

While Hirst’s sculpture looks to be a replica, it also works on a deeper level, evoking faith and art history.

The term, Hymn, is a play on the male pronoun and refers to a devotional song or lyric in which God or a god is praised. This sculpture is neither a lyric nor a song, yet it may be recognized as a picture that depicts a portrayal of a worship item as is customary in idolization across the world, where sculptures are built with the world’s most valuable materials, intricacy, and perfection.

A Belgian Politician (2011) by Luc Tuymans

| Date Completed | 2011 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | Unknown |

| Current Location | Private Collection |

This is a portrait of politician Jean-Marie Dedecker. Tuymans’ restricted color pallet and close-up view are common. The picture’s most striking feature is the harsh cut halfway down the model’s face. The cropping of the photograph has been hotly debated, although mostly in legal rather than artistic aspects.

This is owing to a court case in which Tuymans was found guilty of plagiarism since the artwork was deemed to infringe on the copyright of the image on which it is based.

The original was photographed for the Belgian daily De Standaard by award-winning portraiture and journalistic photographer Katrijn Van Giel and uses the same crop. However, because it is in color, Tuymans’ rendition connotes a newspaper image rather than its printed counterpart.

According to Tuymans’ lawyer, Michael De Vroey, the artist “intended to produce a striking picture to communicate a critique of Belgian society’s march to the right-wing.”

For many years, his career has been concentrated on the utilization of pre-existing photography, which is frequently already published. Tuymans sees this form of operation as analogous to free speech as well as a mode of modern critique. “How can an artist bring the world into doubt with his creations if he isn’t permitted to utilize that world’s images?” his lawyer said.

Appropriation Art is defined as the use of pre-existing items or imagery with little or no modification. Throughout art history, the practice of appropriation has played a crucial role. In the visual arts, creative appropriation is the proper adoption, borrowing, recycling, or sampling of human-made cultural images.

Read also our appropriation art webstory.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is Art Appropriation?

The concept is that the present piece recontextualizes whatever material it draws from, making the production new – which is a critical factor to comprehend in our understanding of appropriation photography and art. Most of the time, the original is still available in its original form. Artistic appropriation, like found object art, is described as the deliberate copying, borrowing, and modifying of earlier imagery, objects, and concepts as an artistic strategy. Appropriation art is alternatively defined as the integration of a physical entity, or even an existing piece of art, into a brand new work of art.

How Long Has Appropriation in Art Occurred?

Many 19th century artists incorporated references to previous artists’ works or ideas. Jean-Auguste Dominique Ingres, for example, created Madame Moitessier’s portrait in 1856. The odd stance was inspired by the well-known antique Roman painting Herakles Finding His Son Telephas (early 2nd century BCE). As a result, the author forged a link between his topic and the Olympian deity. Similarly, works influenced by Delacroix, Jean Francois Millet, or Japanese pictures in his personal possession might be used to identify Vincent van Gogh. However, appropriation art as an art form may be traced back to Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso’s cubist assemblages and collages from 1912 onwards, in which authentic items like newspapers were utilized to signify themselves.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Appropriation in Art – Why Artists Use Existing Elements.” Art in Context. February 28, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/appropriation-in-art/

Meyer, I. (2022, 28 February). Appropriation in Art – Why Artists Use Existing Elements. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/appropriation-in-art/

Meyer, Isabella. “Appropriation in Art – Why Artists Use Existing Elements.” Art in Context, February 28, 2022. https://artincontext.org/appropriation-in-art/.