Fluxus Movement – The Avant-Garde Fluxus Movement Explained

Today, we will be answering the question, “What is Fluxus?” The avant-garde Fluxus movement was an informally structured collective of Fluxus artists from all over the world, with a notable presence in New York City. George Maciunas is widely regarded as the first artist in the avant-garde Fluxus movement and its organizer, describing Fluxus art as “a combination of games, Spike Jones, Vaudeville, comedy, Cage, and Duchamp”. Fluxus artists, like the Dadaists and Futurists preceding them, did not identify with museums’ ability to evaluate the worth of art, nor did they feel that one needed to be educated to examine and appreciate a piece of art.

An Introduction to the Avant-Garde Fluxus Movement

Fluxus artists desired not only that art is accessible to the public, but also that everyone creates art all the time. It is generally quite difficult to characterize Fluxus since many within the Fluxus movement argue that naming the ideology is excessively restrictive and reductive. Unlike earlier creative movements, Fluxus intended to alter the history of the entire world, rather than just that of art. Most Fluxus artists’ overarching purpose was to blur the line between life and art.

History of the Avant-Garde Fluxus Movement

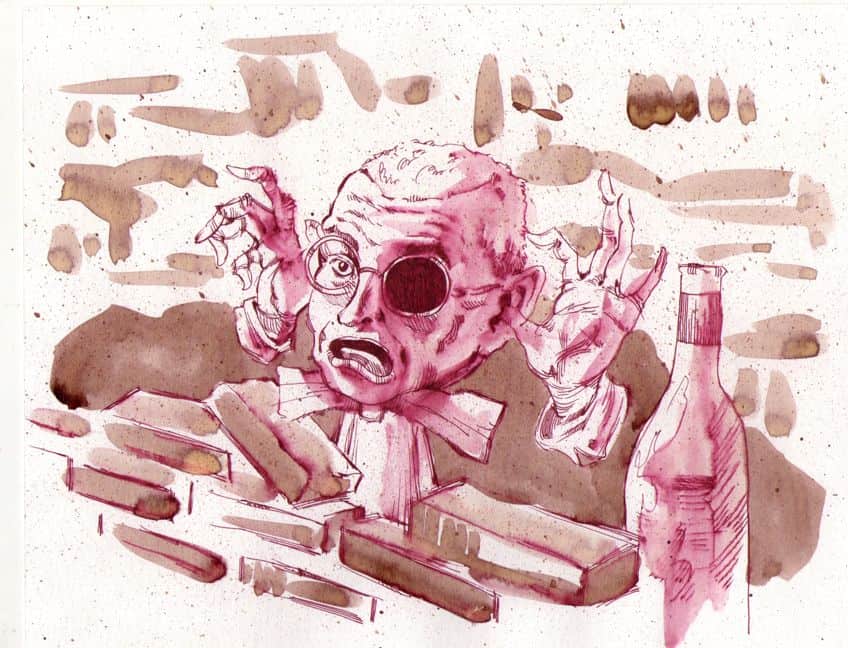

To emphasize the revolutionary manner of reasoning regarding the activity and process of creating art, the first artist in the avant-garde Fluxus movement declared Fluxus art to be “anti-art”. A key Fluxus principle was to ridicule and criticize the elite realm of “fine art“, and to find any means possible to introduce art to the public, which was very much in line with the social mood of the 1960s. Fluxus artists employed humor to communicate their intentions, and the Fluxus movement was one of the few art movements in history to do so, along with Dada. Despite their lighthearted demeanor, Fluxus artists were determined to shift the power structure in the art industry.

Their disregard for “high art” had an influence on the museum’s supposed power to define what and who defined “art”.

The Origins of the Fluxus Movement

Fluxus was founded in the late 1950s by a collection of artists who were dissatisfied with the elitist mentality prevalent in the art industry at the time. These artists were inspired by the Dadaists and Futurists, particularly the performance components of the movements. The use of comedy in art by Dadaists was also significant in the establishment of the Fluxus ethos. John Cage and Marcel Duchamp were the two most powerful influences on Fluxus artists, championing the use of common things and the element of randomness in art, which became the essential philosophy and technique of all Fluxus artists.

The New York Audio Visual Group was founded in 1959 by a collective of artists who had originally all met in John Cage’s class at The New School in New York. This was the beginning of Fluxus, sometimes known as Proto-Fluxus. This organization provided spaces for unconventional and performance art. This ensemble included Dick Higgins, Al Hansen, and Jackson Mac Low, who would later become members of Fluxus. George Maciunas, widely regarded as the driving factor behind what was otherwise a nascent movement, was frequently present in the crowd at the performance locations. Fluxus, meaning “to flow”, is said to have been named by Maciunas. Maciunas staged the inaugural Fluxus event in 1961.

Utopian Fluxus Communities

A few of the group’s artists were keen to start Flux communes in order to “bridge the divide between the creative community and the broader society”. The earliest of these, The Cedilla That Smiles, was created by George Brecht and Robert Filliou at Villefranche-sur-Mer, France, between 1965 and 1968. The business billed as an “International Centre of Permanent Creation”, offered Fluxkits and other tiny items while also operating a “non-school”, with the slogan “A carefree interchange of knowledge and experience.

There are no pupils or teachers. Perfect permission to listen and speak at times.” In 1966, Maciunas, Watts, and many others took the opportunity provided by new laws established to revitalize Manhattan’s “Hell’s Hundred Acres”, shortly to be rebranded as SoHo, by permitting artists to purchase living and working spaces in an area that had been degraded due to a projected 18-lane motorway along Broome Street.

Plans were put out by Maciunas to begin a succession of real-estate developments in the region, with the goal of creating an artists’ community within a few blocks of the FluxShop which was situated on Canal Street.

The first warehouse, on Greene Street, was meant to contain Watts, Maciunas, Christo & Jeanne-Claude, La Monte Young, Jonas Mekas, and others. Maciunas, who compared these settlements to Soviet Kolkhozs, didn’t hesitate to take on the title “Chairman of Building Co-Op” before establishing offices. Over the next ten years, FluxHousing Co-Operatives expanded their plans to include a FluxIsland – an appropriate island was situated close to Antigua, but the funds needed to purchase and advance it remained elusive – and, finally, a performance arts center called the FluxFarm was founded in New Marlborough, Massachusetts. The plans were plagued with financial troubles and continuous run-ins with New York authorities, culminating in Maciunas being badly battered by thugs hired by an unpaid electrical company on the 8th of November, 1975.

The End of the Fluxus Movement

It is argued that Fluxus had come to an end when its creator and leader, George Maciunas, passed away in 1978 from pancreatic cancer complications. Maciunas’ burial was held in classic Fluxus fashion, with the funeral named “Fluxfeast and Wake” with attendees eating only white, black, or purple delicacies. In a series of significant video interviews with Larry Miller, which have been broadcast internationally and translated into several languages, Maciunas shared his thoughts on Fluxus. Miller has recorded and collected Fluxus-related materials throughout the last 30 years, including cassettes on Carolee Schneemann, Joe Jones, Dick Higgins, Ben Vautier, and Alison Knowles, as well as the 1978 Maciunas interview.

Fluxus Art: 1978 – Today

In the late 1970s, Maciunas relocated to Western Massachusetts’ Berkshire Mountains. After collecting artworks for 20 years, the late Boston art collector Jean Brown and her late husband Leonard Brown decided to turn their attention to Surrealist and Dadaist works, manifestos, and journals. In 1971, following Mr. Brown’s death, Mrs. Brown relocated to Tyringham and developed into Fluxus-related fields such as artists’ books, concrete poetry, occurrences, mail art, and performance art. Mrs. Brown alternated between preparing meals and exhibiting people her collection, and Maciunas assisted in transforming her home into a significant hub for both Fluxus artists and researchers.

Activities concentrated on a big archive room on the second level erected by Maciunas, who lived in neighboring Great Barrington, where cancer of the pancreatic and liver was detected in 1977. He married his friend and partner, poet Billie Hutching, three months before his passing. Following a formal wedding in Lee, Massachusetts, the couple held a “Fluxwedding” in a friend’s SoHo apartment on the 25th of February, 1978. The bride and groom exchanged clothes. Maciunas died on the 9th of May, 1978, at a Boston hospital.

Following the death of George Maciunas, a schism developed in Fluxus between a few curators and collectors who saw Fluxus as a definite historical period and the Fluxus artists themselves, many of whom saw Fluxus as a living organism kept together by its essential ideals and world view.

Each of these perspectives was held by different philosophers and historians. Fluxus is therefore alternatively referred to in the present or past tense. While the concept of Fluxus has always been a source of contention, the issue has become substantially more complicated as many of the artists involved who were still alive when Maciunas died are now deceased.

Some say that curator Jon Hendricks’ unique ownership over a large historical Fluxus collection has allowed him to foster the perception that Fluxus perished with Maciunas through the various publications and catalogs financed by the collection. Hendricks contends that Fluxus was a cultural movement that took place at a specific time, claiming that key Fluxus artists such as Nam June Paik and Dick Higgins could no longer be considered active Fluxus artists after 1978 and that contemporaneous artists impacted by Fluxus can also not claim to be Fluxus artists. The same assertion is made by the Museum of Modern Art, which dates the trend to the 1960s and 1970s.

Nevertheless, Fluxus’ impact may still be seen in multi-media digital art performances today. Other Minds performed in the SOMArts building in San Francisco in September 2011 to commemorate the 50th anniversary of Fluxus. Adam Fong, who also performed, curated the performance, which included Alison Knowles, Yoshi Wada, Luciano Chessa, Hannah Higgins, and Adam Overton. Others, such as Hannah Higgins, daughter of Fluxus artists Dick Higgins and Alison Knowles, argue that while Maciunas was a crucial contributor, there were numerous others, including Fluxus co-founder Higgins, who continued to create within Fluxus following Maciunas’ death.

With the advent of the Internet in the 1990s, a strong post-Fluxus community emerged online. After the departure of several of the early Fluxus artists from the 1960s as well as the 1970s, including Higgins, who founded online communities such as the Fluxlist, newer artists, authors, musicians, and performers sought to concentrate their efforts in cyberspace. Many of the initial Fluxus artists who are still active love homages from newer Fluxus-influenced artists who arrange events to honor Fluxus, but they discourage younger artists from using the “Fluxus art” term.

Fluxus Trends and Concepts

George Maciunas had strong beliefs that he constantly and passionately articulated, which usually led to conflict with other Fluxus artists. Maciunas expressed his opinions through Fluxus manifesto pledges, one of which said that fine art, “at least in its institutional forms”, should be “completely destroyed”. Some Fluxus artists disagreed, with Jackson Mac Low declaring, “I would not wish to remove institutions, I enjoy museums”. Maciunas was a temperamental leader who would arbitrarily expel people from Fluxus based on his impulses and had no reservations about dismissing artists for the most trivial of conflicts.

Maciunas ejected Jackson Mac Low from the Fluxus group in 1963, and Alison Knowles, Dick Higgins, and Nam June Paik the following year.

Differing Ideas and Goals

While there was a group of artists that were all deemed Fluxus, they did not all agree on the same goals, and each regarded Fluxus differently. “In Fluxus, there has never been any effort to agree on purposes or techniques; people with something indescribable in common have just congregated to produce and execute their work”, said filmmaker George Brecht. Audience involvement was used during Fluxus events to include the public in the creation of art. Such was the case with Yoko Ono and John Lennon’s Fluxfest performance in 1970 when Maciunas created paper masks of the couple for the public to wear.

With this performance, Maciunas changed the viewer’s role from spectator to actor. The piece’s use of the spectators as the focal point was a natural continuation of his belief that “everything may substitute for art and anybody can do it – the worth of art-amusement must be decreased by making it infinite, mass-produced, attainable by all, and finally generated by all”. Fluxus artists developed more plastic types of artworks, such as boxes containing a variety of objects, prints, and Fluxus pictures, despite the fact that Fluxus is best known for performance art and scheduled events. Sometimes these pieces were not signed since Maciunas believed that the artist’s ego should be eliminated from the art, which meant that all works should be simply ascribed to “Fluxus”.

Zen and Fluxus

Zen is a Japanese Buddhist doctrine that emphasizes meditation and the value of living in the present time. In life, no one moment is more essential than another. Zen had a strong influence on John Cage, who believed that art should just be concerned with value equivalence rather than lifting creative experiences above ordinary experiences – “in this manner, art becomes significant as a method of making one aware of one’s actual world”.

This is strongly related to Buddhist doctrines on the significance of being mindful of being attentive in every moment of life.

Fluxus artists attempted to adapt the ideology to their work. This concept stems from Cage’s seminars at the New School, where several Fluxus artists worked along these lines. Aside from challenging aristocratic art institutions, the flip side of Fluxus was to achieve a type of enlightened condition that included art so much that artwork and life merged into one, with no separation. Despite the fact that Maciunas previously remarked that Fluxus was “more like Zen than Dada”. Maciunas himself was less interested in Zen and more interested in a political, illogical, and anti-art position.

Influences

According to Maciunas, an immediate antecedent of Fluxus was the Gutai group, which championed art as a psycho-physical anti-academic experience, an “art of substance as it is,” as Shiraga Kazuo articulated in 1956. Gutai became associated with a type of creative mass-production, foreshadowing Fluxus’ characteristic, the ambiguity between the cultured and the banal, high and low. Indeed, avant-garde art in Japan leaned toward unstructured instead of conceptual components, starkly contrasting Japanese art’s excessive formalism and symbolism.

Many difficulties relating to the post-war disillusionment felt by many people throughout the industrialized world could be identified in the 1950s New York music scene. Such disappointment gave an argument for committing to Buddhism and Zen in everyday things including meditation, mental attitude, and approach to diet and body care. Nevertheless, it was thought that there was a widespread need for a more radical aesthetic sensibility. In creative domains, concerns of decay and the inadequacy of the concept of modernity were embraced, partially by Dada and Duchamp and partly from awareness of the unease of living in current society.

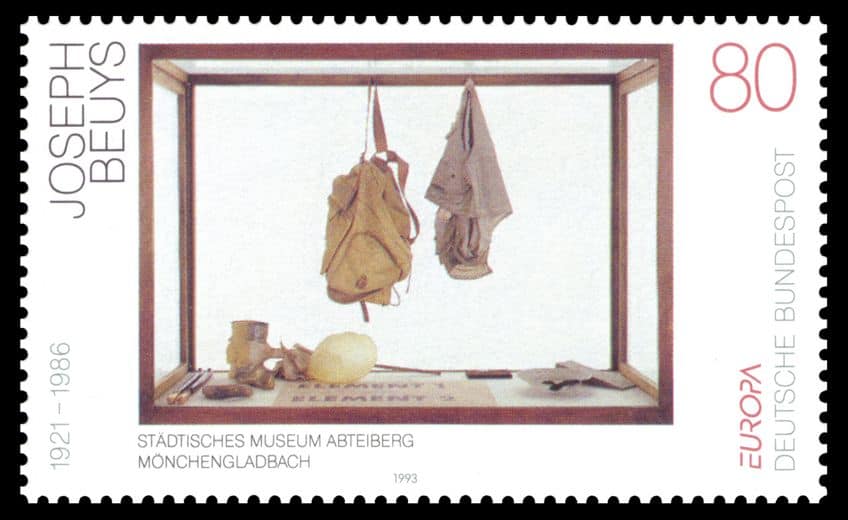

Fluxus is considered to have questioned conceptions of representation, instead opting for straightforward display. This refers to a significant contrast between Japanese and Western art. Another key Fluxus feature was the removal of apparent borders between life and art which was a prevalent theme in postwar art. Joseph Beuys’ paintings and words showed this, as he remarked, “every man is an artist”. Fluxus’ approach was practical and “economic”, as seen by the manufacture of little things composed of plastic and paper.

Again, this aligns well with some of the core qualities of Japanese culture, namely the significant artistic value of ordinary acts and things, as well as the aesthetic enjoyment of frugality. This is also related to Japanese art and the notion of shibumi, which may entail incompleteness and encourages the enjoyment of naked items, stressing subtlety over overtness. The core of Japanese art, according to prominent Japanese aesthetics professor Onishi Yoshinori, is pantomimic since there is no boundary between nature, art, and living. Art is a method of approaching nature and reality in relation to actual existence.

Fluxus Art Style

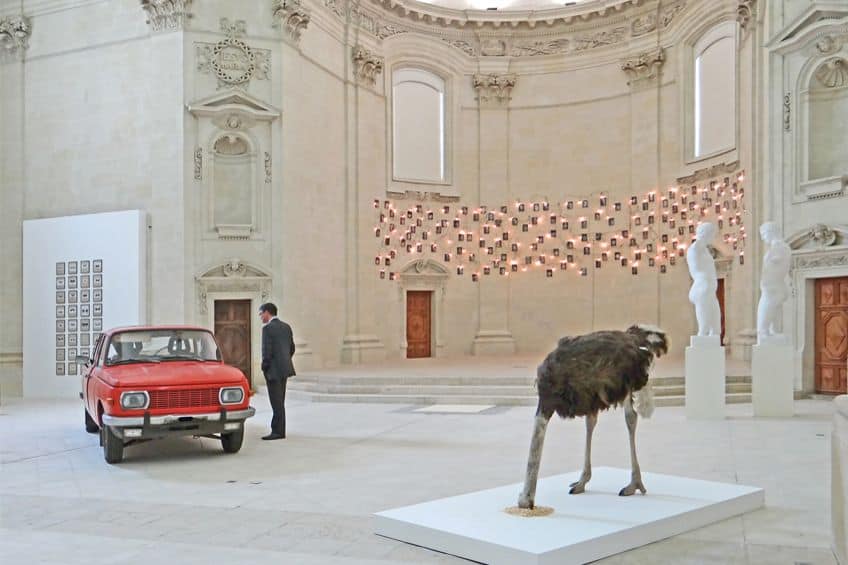

Fluxus promoted a “do-it-yourself” aesthetic that emphasized simplicity over complication. Fluxus, like Dada before it, had a strong anti-commercialism and anti-art attitude, criticizing the normal market-driven art industry in favor of an artist-centered creative approach. Nevertheless, as Fluxus artist Robert Filliou said, Fluxus distinguished itself from Dada in its fuller range of ideals, and the constructive societal and communitarian objectives of Fluxus vastly surpassed the group’s anti-art inclination. Fluxus artists tended to work with whichever materials were available and either developed their own works or cooperated in the production approach with their colleagues.

Outsourcing a portion of the design process to commercial fabricators was uncommon in Fluxus practice.

Many of the Fluxus copies and editions were hand-assembled by Maciunas. While many of the artifacts were constructed by hand, Maciunas developed and intended them for mass manufacturing. Whereas other publishers created signed, numbered products in limited editions for high costs, Maciunas created open editions for inexpensive rates. Several additional Fluxus publishers released other Fluxus editions. The Something Else Press, founded by Dick Higgins, was perhaps the biggest and most substantial Fluxus publisher, releasing books in editions ranging from 1,500 to 5,000 copies, all accessible at ordinary bookstore rates. In a 1966 article, Higgins coined the word “intermedia”.

An events score, such as George Brecht’s “Drip Music,” is basically a performance art screenplay consisting of descriptions of movements to be done rather than conversation. Fluxus artists distinguish between event scores and “happenings”. Whereas these occurrences were occasionally elaborate, protracted performances aiming to blur the barriers between artist and spectator, theater and reality, these event performances were typically fast and straightforward. The event performances aimed to elevate the commonplace, to be attentive to the everyday, and to annoy academic and market-driven art and music culture.

That concludes our look at the avant-garde Fluxus movement. The viewer was involved in Fluxus art, which relied on chance to determine the final outcome of the piece. Marcel Duchamp, Dada, and other performances of the time, such as the Happenings, also used randomness and chance. Fluxus artists were most highly influenced by John Cage’s theories, who felt that one should begin a composition without knowing how it would conclude. The process of creation was more significant than the completed product.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is Fluxus Art?

Fluxus was founded in 1960 by the Lithuanian-American artist George Maciunas as a small yet multinational community of artists and composers and was defined as a common mindset instead of a movement. It was titled after an experimental music journal that presented the work of artists and musicians centered on avant-garde composer John Cage. Fluxus means flowing, and flux is something that flows out. Maciunas, the creator of Fluxus, stated that the group’s goal was to create a radical torrent and tide in art, advocate live art, and anti-art. This is reminiscent of the early 20th art movement Dada.

What Defined the Fluxus Movement?

Fluxus did not have a one-uniting style. Artists employed a variety of mediums and procedures, taking a do-it-yourself approach to creative activity, frequently performing impromptu performances, and making art with whatever resources were available. Fluxus saw itself as an alternative to academic art and music, as well as a democratic form of creativity available to everybody. Collaborations between the artists and throughout art forms were welcomed, as well as with the public or observer. It stressed simplicity and anti-commercialism, with accident and coincidence having a key role in the development of works, as well as humor.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Fluxus Movement – The Avant-Garde Fluxus Movement Explained.” Art in Context. March 8, 2023. URL: https://artincontext.org/fluxus-movement/

Meyer, I. (2023, 8 March). Fluxus Movement – The Avant-Garde Fluxus Movement Explained. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/fluxus-movement/

Meyer, Isabella. “Fluxus Movement – The Avant-Garde Fluxus Movement Explained.” Art in Context, March 8, 2023. https://artincontext.org/fluxus-movement/.