What Is the Purpose of Art? – Find the Purpose and Function of Art

What is the purpose of art? This is a near-impossible question that artists are often asked. What does art do? What is the function of art? What do you intend with your art? People that do not see themselves as creative or do not feel like they resonate with art, often wonder out loud about the fuss. Artists that might feel a bit lost in their practice or just have a moment of disconnection from the “muse” might also scratch their heads about this massive philosophical question. Let us see if there are any answers to the question, “What is the purpose and function of art?”

What Does Art Do?

So, what is the purpose of art? To answer this philosophical question, we first need to ask the conceptual question, “What is art?” We cannot talk about the importance of art if what we understand about art is abstract and confusing.

Art has been defined in many different ways since the dawn of humankind.

We will look at a general timeline of how art’s definition changed only from the first found art until the contemporary moment today. From the history of art, it might be possible to understand what the concept of “art” means and what purpose it serves our species.

A History of Art

This timeline discussed in the sections below is informed by the Western canon of art history. The majority of what has been documented and written about art history is focused on the European tale of art development. Unfortunately, not a lot of other cultures’ artworks have been documented and spoken about as in-depth as Western art.

But as Western societies colonized the world and actively spread Christianity to many parts of the world, we can deduce that these art movements discussed below definitely affected, if not influenced, other world cultures as well.

Prehistoric and Classical Art Movements

During the prehistoric and classical eras discussed below, the function of art changed relatively slowly. The purpose and function of art were generally used as a tool to document mythical, religious, and political frameworks present at the time.

Prehistoric Art (30,000 BC – 1,300 BC)

The first ever human art found speaks about a beautiful and powerful relationship between humankind’s survival, culture, and art. Art served a supernatural, transcendent purpose. Like Terence McKenna says in his 1990 lecture, Opening the Doors to Creativity, the first artists were called shamans, and their role was to translate and communicate messages from the “transcendental other”.

From the Hunter-Gatherers and Ancient Chinese artists to the Egyptians, the importance of ritual and symbols in the making of art is undeniable. All the ancient cultures aimed to capture their understanding of being alive, the forces that created the world, and how we might transcend consciousness.

In the modern Western world, artists are now the only ones allowed to talk about “their inspiration” or “the vision that came to them”. Like shamans, artists are sometimes still believed to have a connection to that which transcends normal human consciousness. This definition and function of art are, however, not highlighted or often not celebrated as the meaning of art has changed since early humans painted our visions on the cave walls.

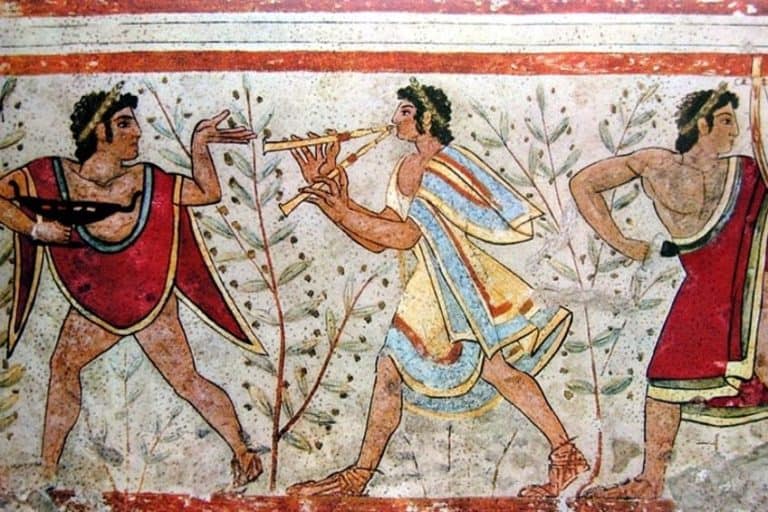

Ancient Greek and Roman Art (800 BC – 100 AD)

During this phase in art history, the rise of naturalism and figurative portrayal became popular. Art and functional objects were combined, with the main form of expression being pottery and sculpture. Painting was also a common form of expression but, as most paintings were created on canvas and murals, very few survived.

The function of art during this time was to depict the rise of the two empires (Greek and Roman) and the belief structures that underpinned these two civilizations.

Even the way they depicted scenes from everyday life was strongly influenced by the myths and religious beliefs of the time. The artists were believed to be influenced by spirits, deities, or entities that reside in the artist’s studio. Therefore, the artists were, still, believed to be the only channels or translators of messages about human life that came from “higher conscious” beings.

Early Christian and Byzantine Art (4th – 15th Century)

Depicting and bringing the Christian tradition to life was the next function of art. Naturalism, emotion, and imaginative power were all expressed in art, but always through the lens of Christianity and the spread thereof throughout the world. This stylized and solemn art movement was believed to be a way to communicate directly with God. The art produced during this time was, therefore, believed to hold holy power. Through the contemplation of and meditation or prayer on religious painted icons, religious leaders could experience messages from God.

This art was carefully regulated.

Where Ancient Greek and Roman art was only accessible to patrons and rich families, Early Christine and Byzantine art were only available to those high up in the church at the time. Art was, therefore, still very mysterious and auspicious. Again, the focus was not at all on the artist as the maker, but the artist was simply a vessel through which God could communicate with humans. Originality, creativity, or personal expression was discouraged. Instead, the artists were encouraged to imitate icons as directly as possible which resulted in copies of the same paintings over and over.

The Middle Ages (6th – 11th Century)

The influence of pagan stylized motifs was incorporated into figurative Christian art to form the only art form that survived the fall of the Roman Empire: manuscript illustration. The art created to illustrate and decorate simplified religious texts had a missionary purpose and was made to support the further spread of Christianity. Even though these religious texts had to be copied exactly, there was more freedom for Christian monks to incorporate designs they saw in pagan metalwork, jewelry, and small sculptures in their illustration of the holy stories.

So, besides being translations of messages from God, these biblical illustrations also had the function of converting non-believers.

Romanesque and Gothic Art (10th – 14th Century)

Art during this period was mainly created in the form of architecture. Again, God was at the center of the function of this art as the massive and stunning cathedrals built were meant to convey the magnitude and power of the Christian God. Entire villages worked for years to build extraordinarily detailed churches, with no one’s name attached to it as the “artist”.

These marvels of architecture were created to celebrate God and the people did not create them for their own joy, but with the idea that they would communicate their devotion to God. This function is evident in the obscure places artistic details were sculpted and paintings added so that it is clear that the art was not created for the human eye, but for God alone.

That being said, the impressiveness of these structures also served a political purpose, as the population of entire kingdoms was often required to work on these projects and pay taxes towards the building of these cathedrals, thereby funding the rising power of Christian churches and their political power in Europe.

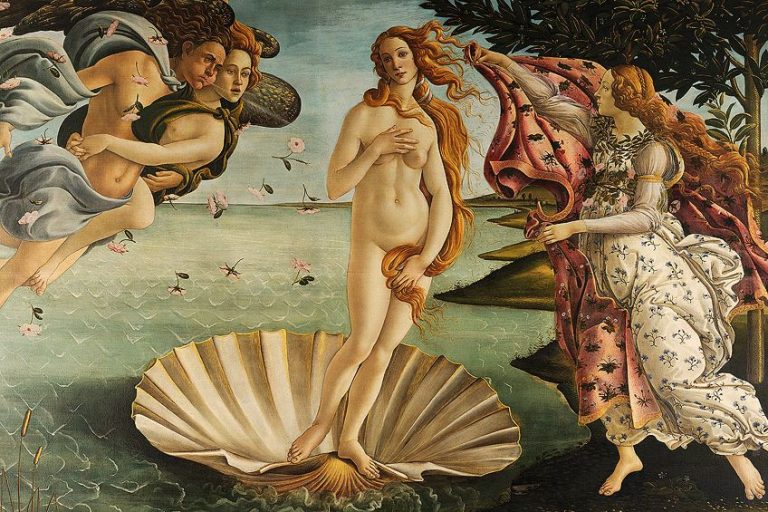

The Renaissance (1300 – 1600)

A split from ancient cultures and art is marked by the rise of the Renaissance. It centered around new humanity and realism that placed humankind and logic at the center of the world. Instead of drawing on classic antiquity, the creations during the Renaissance were focused on meticulous observation, characterized by clarity, harmony, grace, perspective, and skillful complexity.

Moving away from the stylized otherworldly art that preceded the Renaissance, artists during the Renaissance were interested in depicting a realistic sense of three-dimensional space, emotional drama, and more naturalistic events.

Even though they still painted religious scenes (especially during the early Renaissance), it became a possibility for these artists to portray ordinary people – something that (along with the use of perspective) was not done before.

The function of Renaissance art was, thus, to depict the new humanist worldview – a shift from focusing on human achievements or entry into the next world to highlighting their achievements in this life. This changed societal values, and Renaissance art played a very important purpose in documenting and spreading this shift. Another essential function of art at this time was to attain and depict perfection.

Baroque Art (1600 – 1700)

Baroque art, Rococo, and Neoclassicism were known for different things, but overlapped and had one thing in common: they combined the insights and new discoveries of the Renaissance and ancient art to create a new way of expressing themselves.

These art periods came after the hunt for perfection and turned away from the smooth, ideal bodies of the Renaissance to emphasize the drama of human experience and religious scenes even more.

A characteristic of Baroque art is the extreme use of the painting style, chiaroscuro. This dramatic lighting was used to play even more on human emotions when they viewed the art. This marked a shift in art’s function from logical to emotional.

Rococo (1700 – 1780)

Rococo art, on the other hand, left the dark contrasts of Baroque art behind for a lighter depiction and curved lines. Where Baroque art was briefly used to recenter the power of the church after it was slightly de-centered by the Renaissance’s passion for logic and human achievement, Rococo was light-hearted and depicted fun and frivolous activities.

This style originated out of the French royalty’s need to redecorate their old Parisian mansions.

This style was, therefore, a direct indication of the lifestyle and values of the governing powers of France. It spread throughout Europe and became more popular with other rich families and royalty until it was replaced by the more “serious” Neoclassicism.

Neoclassicism (1750 – 1820)

Neoclassic artists attempted to recapture the morals and spiritual values of ancient Greece and Rome. However, as there was so much history between these painters and their idealized ancient predecessors, the mixed influences of how art had changed were evident in their work. The Enlightenment influenced these artists to form a brand-new outlook on the classical world.

Their paintings aimed to convey the values of order, clarity, reason, and scientific study. That being said, after the Revolution in France, it was clear that these works often served a political purpose.

The 19th Century and Its “-isms”

The 19th century is characterized by the speed by which art movements changed picking up. The invention of the camera, and tube paints, and the shifts in power and money in the world during and after the First World War created a rapid redefining of art. The ‘isms (like Romanticism, Realism, and Impressionism) started featuring on the scene and marked this quick change that would extend into the 20th century.

Artists were relieved from their role as documenters and could start depicting the world more creatively from their personal point of view.

Romanticism (1780 – 1850)

Romanticism was the dominant art movement at the beginning of the 19th century. It started in Germany as a literary movement, but quickly spread throughout Europe and started influencing visual artists as well. Instead of perpetuating conservative views through their art, Romantic artists believed that art should be a mode that highlights the individual’s experience, and expresses the rebellion of the imagination.

Romantic artists were not that interested in only depicting the realistic socio-political situations of the time. Rather, art became the means to express intense human emotion, individuality, and imagination experienced during these events.

All of these were expressed and communicated by artists painting unique paintings at the time, depicting personal perspectives and emotions. Francisco de Goya is a good example of a Romantic artist. His painting, The Third of May 1808 (1814) is typical of the Romanticism movement, showing the horrors of personal experiences during the Peninsular War.

The rationalism and order of the Neoclassical period were left behind and as a reaction to the political upheavals of the time, Romantics started placing the notion of individual freedom at the center of art’s function. Spirituality, color, and drama are also key to this movement.

Even though they wanted to move away from Neoclassic ideals and conservative views, the Romantic artists were still inspired by the Gothic art movement, Medieval art, and other Classical art styles. The Romanticism style became a mix of art styles, drawing on styles like Orientalism in the search for an authentic and personal voice.

Romanticism also made use of the sublime forces of nature or using poetry and song the tell the stories of powerful interactions with the forces of nature to convey the sense of overwhelming passion and emotion with which they experienced life. A famous Romanticism landscape painting is Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog (1818) by Caspar David Friedrich.

The Pre-Raphaelite Movement (1848 – 1900)

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood was a revolutionary art movement that prompted the depiction of a new kind of female beauty amongst other things. This group of artists was unhappy with the way the Royal Academy in London was teaching and restricting artistic expression. They wanted to find new ways of expression by drawing on the art of Italian painting before Raphael (1483-1520).

This movement started in Britain while the country was going through rapid industrial change. As wealth was growing because of this speedy industrial growth, new patrons interested in art started supporting artists.

The Great Exhibition took place during this period, which shows the keen support of the arts, design, and innovation by Prince Albert himself. However, many people were being exploited to fuel the industrial doom and citizens were threatening revolution, asking whether life had been better before industrialization.

Tensions between the old world and the new world catalyzed the Pre-Raphaelite style of painting religious, natural, and societal phenomena in new ways using old modes. They aspired to capture everything as true to nature as possible, resulting in meticulous attention to detail.

These artists rejected painting on a canvas prepared with earth tones first, which resulted in a brand-new, vibrant style of color use.

The purpose of art for them became a way to – as accurately as possible – depict scenes from history and the Bible. They spent a lot of time researching costumes, accessories, and historical details to get the perfect compositions. A well-known painting from this period is The Awakening Consciousness (1853) by William Holman Hunt.

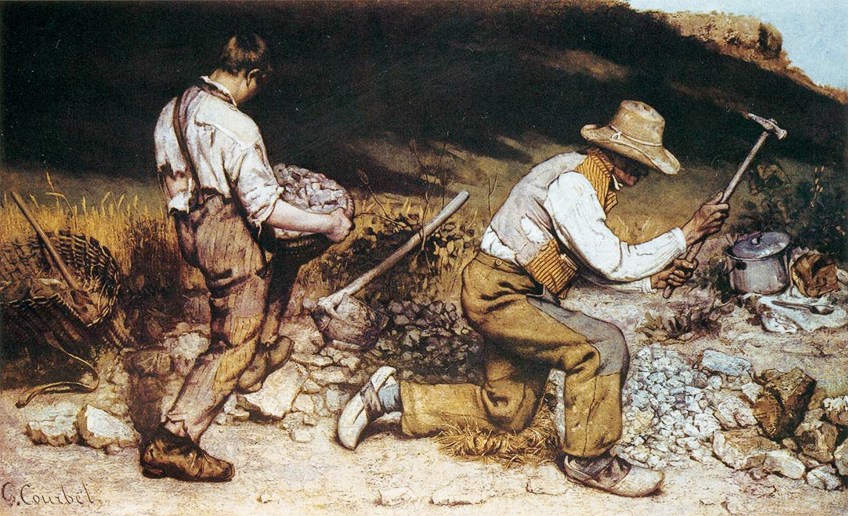

Realism (1850 – 1900)

The Realist artists of the 19th century reacted to the 1848 Revolution in France and the Romantics of the previous period by making art focus only on the real life the artist lives. Realism was a rebellious movement that rejected the depictions of the mythical, historical, and religious subjects of the past. The purpose of art was to capture (like the camera that was not accessible to everyone yet) exactly what was seen by the artist.

For the first time in art history, the painting of peasants, workers, beggars, prostitutes, and so on were done with no deeper meaning or political motivation, but simply because it was the reality the painters saw every day.

These scenes were often decidedly unpretty and are characterized by bold lines, a somber palette, and intense tonal contrasts – all adding to the energy and robustness of the work. Gustave Courbet led this movement and his well-known painting, The Stonebreakers (1849) is a typical example of this realistic style.

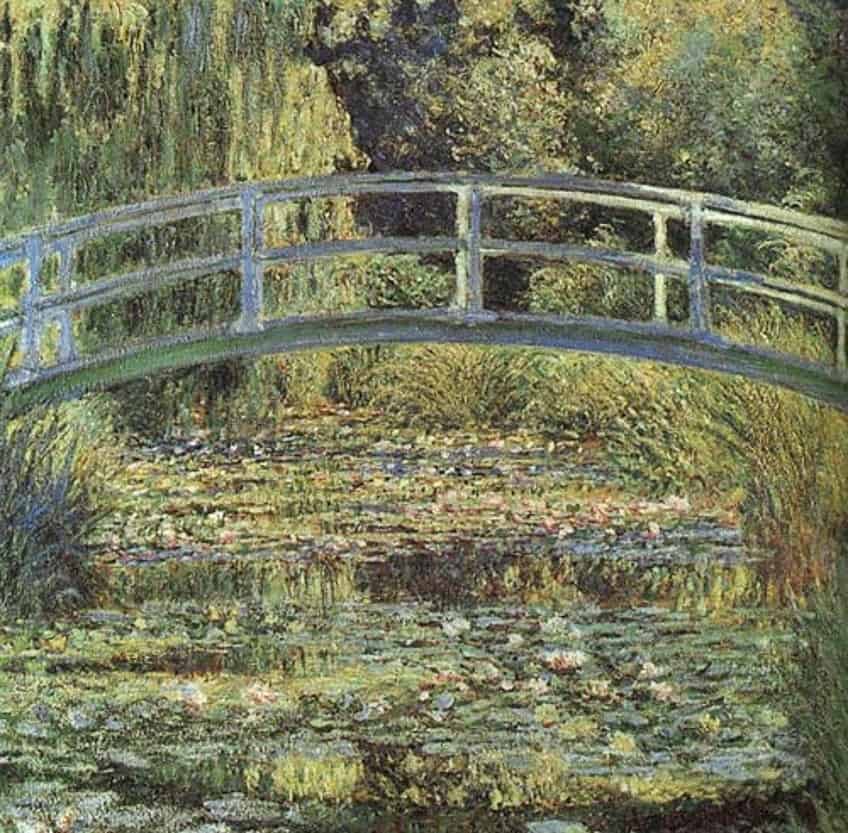

Impressionism (1860 – 1900)

The Impressionists were, yet again, a group that desired to express themselves outside the constraints of academic art and the Paris Salon. This group, however, kickstarted a rapid redefining of art by crossing boundaries never crossed before within the canon of Western art: they painted scenes of contemporary life like their eye would see it, in fleeing moments, with flickering brushstrokes and blobs of unmixed paint.

The core function of art for them was interpreting the world through their own eyes and capturing this interpretation through art.

Trains made the connection between the countryside and the city easily accessible. New gas lamps lit up the nightlife of the city. The camera released artists from their role as documenters and gave them reference photographs to work from for the first time in history. Tube paint made plein-air painting a new way of capturing their surroundings and allowed artists to leave the studio and be among the subjects they painted. All these elements of modernization and the Industrial Revolution gave artists brand-new subjects and more freedom to express themselves in ways never done before.

The purpose and function of art became centered on capturing the immediate, fleeting moment. These painters, when painting nature, tried to capture the movement and reflection of light. In this way, they created the most alive, moving, and vibrant paintings are done up to that point.

It was absolutely revolutionary and catalyzed the fast-changing definitions of art we are used to today as more and more artists started pushing the limits of what art does.

The Waterlily Pond, Green Harmony (1872) by Claude Monet shows the characteristically short and small brush strokes, vibrant colors, the effects of light, and the sensations of a landscape, for example, produced by the Impressionists.

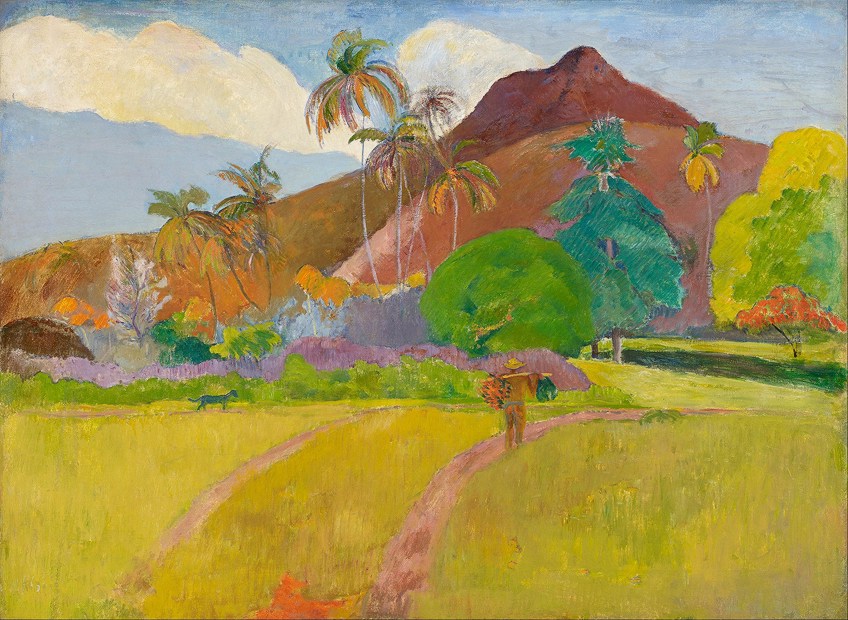

Post-Impressionism (1885 – 1905)

Post-impressionists reacted against the idea that artists should simply paint the scene they perceived. They wanted to do more. These artists all started as Impressionists but were struggling to make a name for themselves. In a world where Western power was increasingly colonizing the rest of the world, the art of other cultures and new places to live in became accessible to creatives. The Post-Impressionists started drawing inspiration from these new sources, and the influence of Japanese prints, for example, on the artists Gauguin and van Gogh became clear.

The Post-Impressionists were, therefore, interested in using art to depict the rest of the world that had just become open to them.

These artists used art to create images full of emotion, that seemed to speak past its direct interpretation and were a mix of different artistic styles from around the world. Some of these painters pushed the short brushstrokes of the Impressionists even further by meticulously putting dots of color next to each other to influence the emotions evoked by the paintings.

Symbolism (1875 – 1910)

In reaction to the materialism and rationalism of the modern world, Symbolist artists started creating art that focused on one’s imagination and emotions. They drew inspiration from the occult, psychology, and mystical ideas. Besides psychology developing, there was also a new interest in spirituality in French society.

The Symbolists processed these new ways of thinking through their art.

They wanted to make the invisible visible and this became the purpose and function of their art. They started exploring dreams, sleep, visions, stillness, silence, and female sexuality. The exploration of death and sex through styles influenced by the Art Nouveau movement (which ran parallel to the Symbolism movement) is evident in The Kiss (1907-1908), for example, by Gustav Klimt.

20th Century: The Modern Age

Art changed so much throughout the 20th century that it is sometimes not even possible to pin down a concrete function of art for longer than a decade. In the contemporary moment, art does whatever the artist wants it to do. How we got to this open and fluid purpose and function of art is due to what took place in art history during the Modern art period.

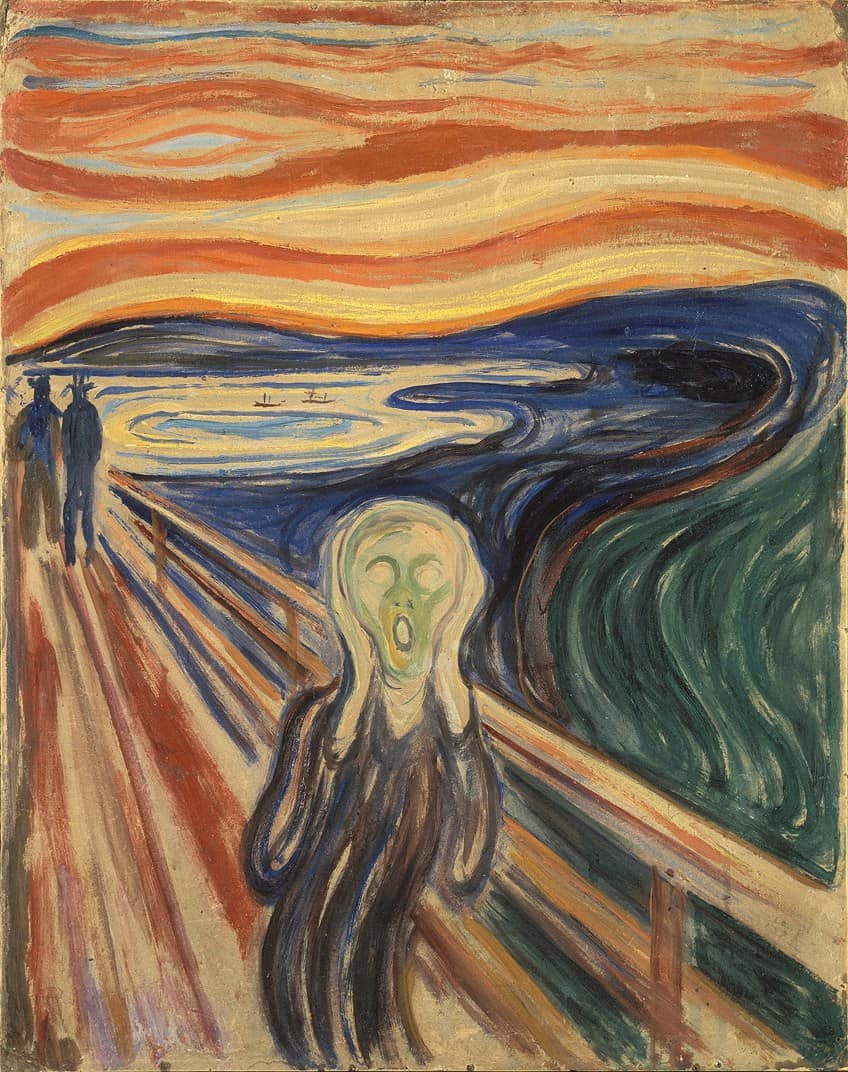

Expressionism (1895 – 1995)

Expressionists were interested in expressing intense emotion through their artwork. Unlike the Impressionists, Expressionist artists were not interested in showing their interpretation of the world. They also did not work with the natural environment to produce art that captures the immediacy of light.

They created brand new scenes with difficult emotions often at the center of the work. In order to do this, they distorted forms and painted vivid colors straight from the tube.

The world was changing quickly, technology developing fast, and tensions rising before the first World War. There was a sense of alienation in the world and artists wanted to capture this. They moved away from realism. Fauvism, a subdivision example of Expressionism, used bright colors connected to specific meanings to convey deep feelings.

Expressionism mainly developed in Germany and the artists Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Franz Marc, Paul Klee, and Marc Chagall were at the center of the movement. The Scream (1893, 1910) series by Edvard Munch shows the utter breakdown of realistic depictions in swirls of color and intense, distorted imagery.

Cubism (1907 – 1920)

At this point in art history, photography was very popular and widespread. Cars, airplanes, and the cinema were part of most European people’s lives in some way or another. Artists really started taking advantage of the freedom the camera gave them and also started using insights brought on by the photograph in their art. For example, Cubist artists became interested in depicting scenes, objects, and people from different angles at the same time.

Art became a means by which artists could explore, redefine, and repurpose the gaze, perspective, and form.

The extension of the world through traveling, technology, science, and communication was processed through this art period by using art as a means to express this connection. Through the geometric lines, and intense distortions of form and perspective, Cubist artists like Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque captured the spirit of change present in their world.

Abstract Art (1910 – 1940)

Abstract art, even more than any other art form that preceded it, aimed to move completely away from depicting anything resembling real life. This is the only characteristic of this vast and long-lasting art movement. The color application, medium, subject, and so on can be very different. But as long as what is depicted is abstracted it can be called Abstract art.

The function of abstract art is, therefore, to give expression to that which is not visually literal- to allow artists to explore abstraction while still conveying meaning and evoking emotion.

The power of color, line, texture, tone, and form is at the center of this movement. The first Abstract painters came after the First World War and used this way of abstraction to explore the limitless potential of art to give expression to their feelings and the new worldview. Artists like Wassily Kandinsky (1866-1944) came out of the Abstract art movement.

Dadaism (1915 – 1950)

The Dada art movement started as a protest against the civilization that had, at the point, erupted the world into war. It was a way for artists to explore the absurd and completely nonsensical. Their idea was that absurd art was the only thing that could reflect the absurdity of society.

The readymade idea came out of Dadaism and changed the course of art forever.

Marcel Duchamp, for example, placed an upside-down urinal with the signature “R. Mutt 1917” on show and called it Fountain (1917). This caused much controversy in the art world and raised the question of “what is and is not art” to the extreme.

Surrealism (1915 – 1950)

Surrealism was also interested in questioning the accepted ideas of society; however, these artists pushed the absurd and the strange in their art in a different way. They used the ideas of the unconscious mind, automatism, and symbolism from Freudian psychology to create compositions that look super real but utterly otherworldly. All of this was done to create a kind of “superior” reality.

Artists such as Man Ray, Salvador Dalí, and René Magritte formed part of the Surrealist movement.

Abstract Expressionism (1940 – 1959)

Abstract Impressionism was interested in improvised, expressive, and movement-based works of art that conveyed intense emotion. This movement was inspired by Surrealism’s ideas connected to intuition and the unconscious mind.

It started in America during World War I and continued throughout the Great Depression.

Artists from Europe were fleeing the Second World War and had a great influence on US artists. Abstract Expressionism became the first, uniquely American art movement, with Jackson Pollock being the most famous painter to come out of it.

Pop Art (1950 – 1980)

Post-war Pop art burnt the final boundaries on the definition of art and initiated the Post-Modern contemporary art we still know today. The function of Pop art was to finally break down the barriers between fine art and popular culture.

These artists used books, films, photographs, advertisements, comics, illustrations, and packaging to create collages and juxtapose art with a variety of mediums and references.

This art movement wanted to make art more accessible to everybody. Andy Warhol’s contentious Campbell’s Soup Can (Tomato) (1962) prints are a famous example of Pop art.

In Conclusion: What Is the Purpose of Art?

What happened after these distinct art movements was essentially a total breakdown of anything that bordered the traditional interpretation of art. Sound art, computer art, performance art and so many other non-tactile art forms started developing. Artists are always pushing the definition of art with it sometimes being absolutely bizarre and nonsensical. Movements like Expressionism and Abstract art are still present and distinctly recognizable.

But in fact, contemporary art draws on all of the art movements of the past to create an eclectic and highly personal art style dependent on the artist.

It also becomes clear from the timeline discussed above that most of what pushed art forward to find new purposes was the reactions against the existing modes of expression. Artists have always drawn inspiration from art history to create diverse and new ways of depicting their worlds.

Furthermore, most of the development of art was catalyzed by violent socio-political circumstances that forced people to search for ways to express the upsetting and often indescribable realities they live in. Art has, therefore, always been a mode through which humans make sense of the world and its function is, therefore, dependent on whichever complex situation humans find themselves baffled by.

So, what does art do? This a difficult question to answer as it depends on the intention of the artist. Our definition of art keeps changing and, therefore, coming to a definitive understanding of the purpose and function of art is nearly impossible. In this discussion of the Western history of art, this fact becomes very apartment. Art has played a role in how our cultures have developed, and how we make sense of spirituality, emotion, the mind, as well as all other aspects of human life.

Take a look at our purpose of art webstory here!

Frequently Asked Questions

What Does Art Do?

Art does whatever the artist intends plus how it is received by the viewer. In the past, especially during the ancient and classical art periods, art had a very specific function, but in the post-post-modern world, the purpose and function of art are growing increasingly unclear.

Why Is Art Important?

Art is important to humans in the same way that language is important. Besides the fact that it gives us a different way of communicating, it is also something humans have just done for ages. There is not one reason why art is important, but the fact that we have always made it shows that humans are indistinguishable from art.

What Is the Purpose and Function of Art?

The purpose and function of art, as well as the definition of art, keep changing. In general, the purpose and function of art are often dictated by those in power as art is often used to change people’s minds about certain political, societal, cultural, and emotional phenomena. This means that there is not one purpose of art that can be applied universally, but that art’s function changes from period to period and artist to artist.

Nicolene Burger is a South African multi-media artist, working primarily in oil paint and performance art. She received her BA (Visual Arts) from Stellenbosch University in 2017. In 2018, Burger showed in Masan, South Korea as part of the Rhizome Artist Residency. She was selected to take part in the 2019 ICA Live Art Workshop, receiving training from art experts all around the world. In 2019 Burger opened her first solo exhibition of paintings titled, Painted Mantras, at GUS Gallery and facilitated a group collaboration project titled, Take Flight, selected to be part of Infecting the City Live Art Festival. At the moment, Nicolene is completing a practice-based master’s degree in Theatre and Performance at the University of Cape Town.

In 2020, Nicolene created a series of ZOOM performances with Lumkile Mzayiya called, Evoked?. These performances led her to create exclusive performances from her home in 2021 to accommodate the mid-pandemic audience. She also started focusing more on the sustainability of creative practices in the last 3 years and now offers creative coaching sessions to artists of all kinds. By sharing what she has learned from a 10-year practice, Burger hopes to relay more directly the sense of vulnerability with which she makes art and the core belief to her practice: Art is an immensely important and powerful bridge of communication that can offer understanding, healing and connection.

Nicolene writes our blog posts on art history with an emphasis on renowned artists and contemporary art. She also writes in the field of art industry. Her extensive artistic background and her studies in Fine and Studio Arts contribute to her expertise in the field.

Learn more about Nicolene Burger and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Nicolene, Burger, “What Is the Purpose of Art? – Find the Purpose and Function of Art.” Art in Context. November 9, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/what-is-the-purpose-of-art/

Burger, N. (2022, 9 November). What Is the Purpose of Art? – Find the Purpose and Function of Art. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/what-is-the-purpose-of-art/

Burger, Nicolene. “What Is the Purpose of Art? – Find the Purpose and Function of Art.” Art in Context, November 9, 2022. https://artincontext.org/what-is-the-purpose-of-art/.