Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres – A Master of Neoclassicism

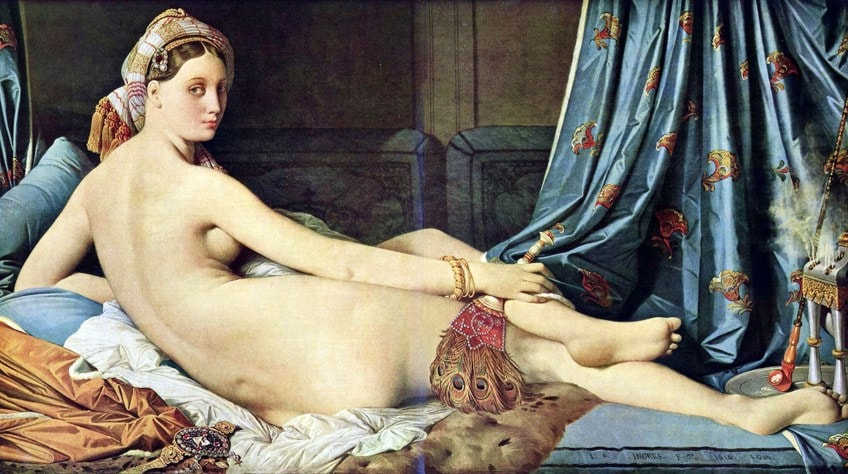

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres was a French artist who was part of the Neoclassicism movement in the 1800s. Ingres’ paintings such as La Grande Odalisque (1814) displayed his desire to maintain the principles of the academic art traditions in defiance of the emerging Romantic movement. Although Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres regarded himself as a historical painter, it was actually his portraiture that was widely recognized as his most important work. To discover all the fascinating details of this renowned artist’s life and art, let us now take a look at Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres’ biography.

Table of Contents

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres’ Biography and Artworks

| Nationality | French |

| Date of Birth | 29 August 1780 |

| Date of Death | 14 January 1867 |

| Place of Birth | Paris, France |

Ingres’ paintings were known for their blend of tradition and a sense of sensuality, much like the work of the master under which he apprenticed, Jacques-Louis David. His work was inspired by the Renaissance era and the Classic style of the Greco-Roman periods, yet was reinterpreted to suit 19th-century sensibilities. Ingres’ paintings were appreciated for their curving lines and incredibly detailed textures. He also had his detractors though, who were not impressed by his attempts at abstracting figures and deeper subject matter.

Despite being seen as the gatekeeper of traditional art styles, his own art was in many aspects a mixture of both Neoclassicism and Romanticism, although not nearly as dramatic as the works of Romanticists such as Eugène Delacroix.

Early Years

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres’ father was a very creative and artistic individual who was known to be a successful musician, sculptor, and painter and encouraged the artist from a young age to learn both art and music. His formal education began in 1786 but was interrupted a few years later by the French Revolution, resulting in the closing of the school he attended in 1791, and with it the end of his schooling. The fact that he felt insufficiently educated would always be a source of embarrassment for the artist.

Ingres’ father took him to Toulouse in 1791, where he enrolled in the Academy of Painting and Sculpture. He received formal instruction from several notable artists at the academy such as Jean Briant, Jean-Pierre Vigan, and Guillaume-Joseph Roques.

At the academy, his talents were honed and recognized early on, and he won several prizes in various disciplines ranging from life studies to figures and composition. At that time, being a history painter was regarded as the pinnacle of artistic achievement at the academy, so Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres strove from an early age to reach that goal. Unlike his father’s works, which depicted scenes of everyday life, Ingres’ paintings were intended to glorify the heroes of history and mythology, produced in a manner that made their characters and intentions clearly visible to the viewer.

Paris (1797 – 1806)

In 1797, Ingres won the first prize for one of his sketches at the Academy, and he was sent to Paris to study at the school of Jacques-Louis David, where he was instructed for four years and was influenced by the Neoclassicism style of the master. As a student at the school, Ingres was said to be one of the most focused artists in attendance, steering clear of the boyish games and follies and dedicating himself to his art with incredible perseverance.

It was during this period that his unique style began to develop, displaying figures that were rendered with amazing detail and attention to the portrayal of the human physique, yet had a distinct exaggeration of certain elements.

From 1799 to 1806, he would win multiple prizes for his paintings and drawings, including the Prix de Rome, which entitled him to study in Rome for four years under the financial support of the academy. However, there was a lack of funds available and his trip was postponed for several years. During this period the state provided the artist with a workshop, and here Ingres’ style was developed further, with a notable emphasis on the purity of form and contours.

He started exhibiting his works in 1802, and the paintings that were produced over the next few years would all be appreciated and lauded for their precision and highly detailed brushwork, especially regarding the fabric textures and patterns. His unique mixture of accuracy and stylized forms became more apparent during this period too.

From around 1804, he also started producing more portraits that featured delicately colored females with large oval-shaped eyes and subdued expressions.

This initiated a series of portraits that would further refine his distinctive style and make his portraiture the most significant element of his oeuvre, as well as make him one of the 19th century’s most loved portrait painters. Before leaving for Rome, Ingres was taken to the Louvre by a friend to see the works of Italian Renaissance artists that had been brought to France by Napoleon. At the museum, he was also exposed to the art of Flemish painters, and both of these styles that he encountered there would affect his own works, incorporating their large scale and clarity.

Due to the influx of artworks and styles brought to the Louvre by the Napoleonic looting of other countries, many French artists such as Ingres began to display a new tendency among themselves to combine these imported styles in eclectic ways.

It was the first time that such a large representation of historical European art was available to them, and artists would swarm to the museums to try and interpret, dissect, and study every aspect of these masterworks: the first attempts at a scholarly study of art history.

Ingres was able to examine artworks from many eras and determine which style would best fit the subject or theme of his own works. This notion of borrowing styles was frowned upon by certain critics, though, who saw it merely as a blatant plundering of art history. Before leaving for Rome in 1806, he created a portrait of Napoleon called Napoleon I on His Imperial Throne. The majority of the painting focused on the ornate and detailed Imperial attire he had worn at the first council as well as all the emblems and symbols of power. This painting, along with several others, was displayed in the 1806 Salon.

Rome (1806 – 1814)

At the time of their display, Ingres had already moved to Rome, where friends sent him clippings of the negative criticism his exhibited paintings were receiving. It infuriated him that he was not there to defend the works himself and that the critics had pounced on them as soon as he had left. He stated that he would continue to develop his style to a point where his works were far removed stylistically from what he considered to be the inferior works of his peers and swore to never return to Pair or exhibit at the Salon ever again.

His decision to remain in Rome would ultimately lead to the end of his relationship with his fiancé, Julie Forester.

He wrote to Julie’s father, explaining that art was in serious need of reform and that he intended to be the one to revolutionize it. As was expected of all Prix recipients, Ingres sent his paintings to Paris regularly so that his progression could be reviewed. Fellows of the Academy often submitted works of masculine Roman or Greek heroes, but for his first piece, he sent La Grande Baigneuse (1808), a portrait of the back of a naked bather and the very first Ingres figure to wear a turban, which was a stylistic feature he copied from his favorite artist, Raphael.

Ingres’ paintings from this period continued to display the artist’s desire to create realistically rendered paintings that exaggerated certain aspects of the forms, yet this meant that he never fully won over either side of academics or critics, as some felt that his works were not stylized enough, while others found them too exaggerated.

After the Academy (1814 – 1824)

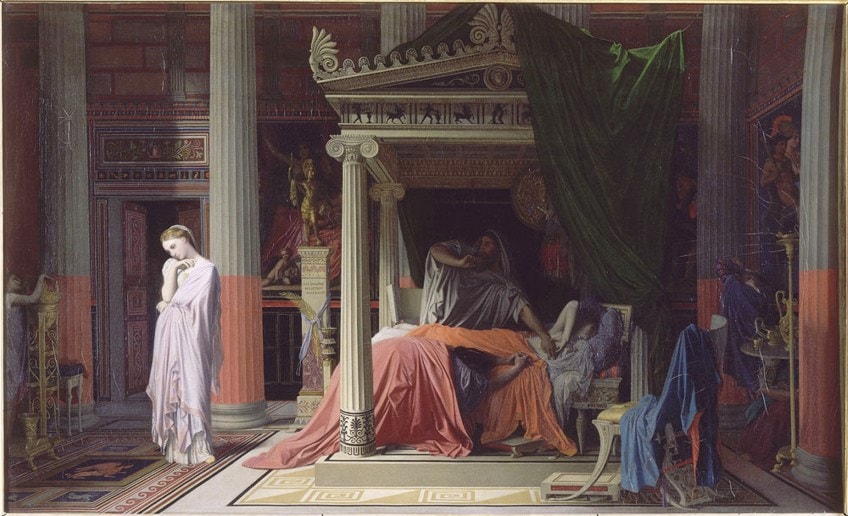

Upon leaving the academy, Ingres was offered several significant commissions. One of those was from a prominent art patron, General Miollis, who commissioned Ingres to paint the rooms of the Monte Cavallo Palace ahead of Napoleon’s anticipated visit. In 1814, he traveled to Naples to paint a portrait of the king’s wife, Caroline Murat. The monarch also commissioned several more works, including one that would become regarded as among the finest of Ingres’ paintings, La Grande Odalisque (1814).

However, the artist would never receive any money for these paintings as Murat was executed the following year following the fall of Napoleon, and Ingres was suddenly in the position of being stuck in Rome without any financial support from his usual patrons.

Commissions were few and far between, yet he continued to create portraits in his almost photorealistic style. To supplement his meager earnings, he produced pencil portraits for English tourists who were plentiful in Rome after the war had ended. Despite it being something that he had to do to make ends meet, he despised producing these quick tourist pieces, wishing he could return to creating the paintings he was so famous for.

When tourists would come around to his place asking for the sketch artist, he would reply that he was a painter, not a sketcher, but that he would do it anyway.

He was a man who knew his worth, but was resigned to the fact that he had no other option at that point. Despite his own personal feelings towards these sketches, the 500 or more that he produced during this period are today considered among his best pieces.

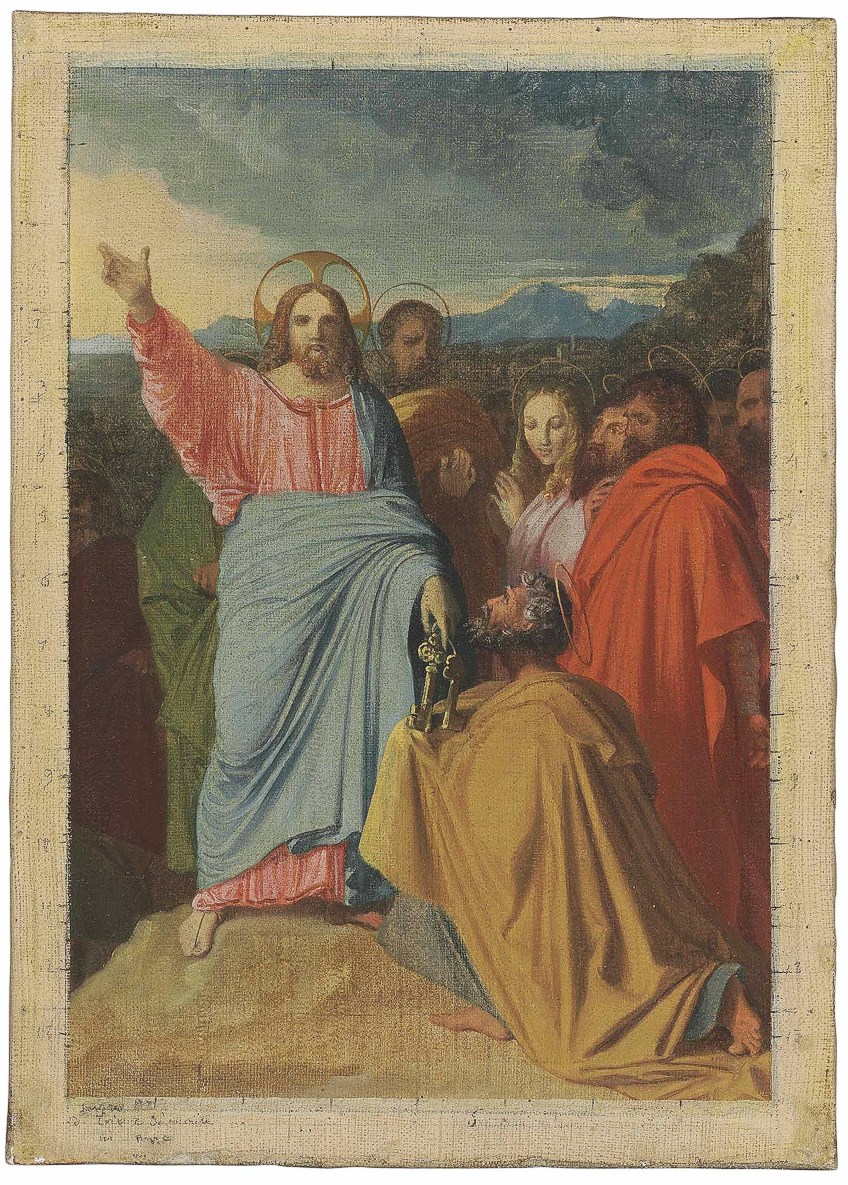

Ingres received his first formal commission in more than three years in 1817, from the ambassador of France, for a picture of Christ Giving the Keys to Peter. This massive piece, produced in 1820, was highly regarded in Rome, but to the artist’s surprise, the church leaders there would not allow it to be brought to Paris for an exhibit.

Ingres was not always able to complete a commission though, especially if it was in opposition to his own moral beliefs. He was once asked to create a portrait of the Duke of Alva, but Ingres despised the Duke so much that he found himself reducing the size of the figure on the canvas until it was barely a spot on the horizon, before giving up on the piece altogether.

In his journal, he later wrote that a commission might have asked for a painter’s masterpiece, but fate had decided that it would be nothing more than a sketch. Despite his initial assertion that he would not send art to the Salon, he once again submitted work in 1819, sending La Grande Odalisque (1814), along with several others.

Once again, though, Ingres’ paintings were met with strong criticism, with reviewers stating that the female figure was reclining in an unnatural pose, that her spine had too many vertebrae, and that overall, the figures looked flat, and without any discernable muscle tone or bones.

To them, it looked like he had simply tried to copy various poses from the paintings of antiquity that he admired, and combined them in a poorly executed way, leading to a spine that seemed oddly elongated and contorted. After relocating to Florence in 1820, Ingres’ future started to look a little brighter. Roger Freeing Angelica (1819), a piece that was bought by Louis XVIII to be hung in the Musée du Luxembourg, was the first of Ingres’ paintings to be displayed in a museum.

Return to France (1824 – 1834)

Ingres was finally met with success with the exhibition of The Vow of Louis XIII (1824) at the 1824 Salon. It was lauded by many, yet still received criticism from some detractors who were not impressed with artworks that glorified material beauty without any reference to the Divine.

At the same time as his style was gaining in popularity, the artworks of the emerging Romanticism movement were simultaneously exhibited at the Salon, a stylistically sharp contrast to Ingres’ paintings.

In 1834, he completed The Martyrdom of Saint Symphorian, a massive religious artwork depicting the first saint in Gaul to be martyred. The bishop chose the theme of the artwork, which was commissioned in 1824 for the Cathedral of Autun. Ingres saw the artwork as the culmination of all his skills, and he focused on it for almost a decade before debuting it at the 1834 Salon. The reaction surprised and enraged him; the picture was criticized by both Romantics and Neoclassicists alike.

Ingres was criticized for historical inaccuracies, for the colors, and for the Saint’s feminine figure, which reminded them of a statue. Ingres became furious and swore he would never take public commissions again or appear in the Salon.

Ingres eventually took part in various semi-public exhibits and a retrospective of his works at the Paris International Exposition in 1855, but he never again presented his work for public evaluation.

Academy of France (1834 – 1841)

Instead, he traveled back to Rome towards the end of 1834 to serve as the Academy of France’s director. Ingres stayed in Rome for six years, devoting most of his time to the instruction of painting students. He remained infuriated with the art establishment in Paris and turned down several commissions from the French authorities. He did, however, create several smaller works for a few French patrons around this time, mostly in the Orientalism style.

Last Years (1841 – 1867)

Eventually, Ingres would return to Paris in 1841 and would remain there for the rest of his life. He went on to teach at Paris’ Ecole des Beaux-Arts. He regularly took his pupils to the Louvre to see ancient and Renaissance artworks.

However, he would advice them to stare directly ahead and to ignore Rubens’ paintings, which he thought strayed too far from the fundamental qualities of art.

In the last few years of his life, he was still a very prolific painter, producing works such as The Turkish Bath (1862), which would become one of his most renowned paintings. On the 14th of January 1867, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres passed away from pneumonia.

All of the artwork in his studio was given to Montauban’s Museum, which has since been renamed the Musée Ingres.

Recommended Reading

That covers it for Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres’ biography for this article. But maybe you are keen to know even more about his life and Neoclassicism artworks. If so, check out one of these interesting books, as they will provide further insight into Ingres’ paintings and lifetime.

Portraits by Ingres: Image of an Epoch (1999) by Philip Conisbee

This study of portraits by Ingres was published to complement an international exhibit. They were produced throughout the first 70 years of the 19th century and were hailed as “the truest representation of our period” by a reviewer in 1855. The book includes a variety of original source materials, such as critical reviews, letters, biographical records, and photographs.

- A study of the portraits by painter Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres

- Brings together a wide range of original source materials

- Reproductions of his major works and over 100 drawings and studies

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (2010) by Eric de Chassey

This book is about the Jean-Auguste Dominique exhibition in Rome. It was a presentation that represented the new approach to French and American relations by highlighting the two nation’s historical and cultural links. The collection includes a number of sketches and paintings by Ingres that were originally in the Louvre.

- This catalog reflects the striking visual narrative of the exhibition

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres was clearly an artist with exceptional talent. Yet, it was his desire to add a unique twist to the traditional classical style by embracing forms that were exaggerated in a manner that amplified the curves of his figures. In many ways, this combination of the classic style of drawing figures and his inclination towards the idealized did not mix well with many people on either extreme, whether the traditional Classicists or the emerging Romantics. Despite all these criticisms, he stuck to his unique style in his paintings, which would eventually become appreciated as some of the best works of the era.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Style Were Ingres’ Paintings?

He was most known for his Neoclassical paintings. Ingres’ style developed early in his life and changed rarely. His early works display a skillful use of outlines. Ingres disliked theories, and his devotion to classicism, with its stress on the idealized, universal, and orderly, was balanced by his adoration of the unique. Ingres’ subject matter mirrored his very restricted literary tastes. Throughout his life, he returned to a few favorite themes and produced several copies of a number of his significant works. He did not share his generation’s excitement for battle scenes, preferring to represent moments of enlightenment. Though Ingres was recognized for following his own inclinations, he was also a devoted follower of traditionalism, never deviating totally from Neoclassicism’s contemporary yet conventional views. Ingres’ precisely drawn paintings were the opposite aesthetic of the Romanticism school’s colors and emotions.

Did People Like Ingres’ Paintings?

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres was regarded as an exceptional artist by many people, hence his illustrious career in the art world and service in major art institutions. Yet, that does not mean that he was without any detractors. In fact, winning over critics would not prove to be an easy task for Ingres, as they often viewed his art from the perspective of one or another art movement that did not fully encompass all that his work entailed. Therefore, they would often find his work too idealized if they were looking for signs of accuracy, and yet not idealized enough for many of his peers in the Neoclassical tradition.

What Are the Characteristics of Ingres’ Paintings?

Ingres was unquestionably one of the most adventurous artists of the 20th century. His never-ending quest for the perfect human form, especially relating to the feminine body, was the source of his very controversial anatomical deviations. He had a tendency to make people’s backs longer, prompting critics to note that the spine had several more vertebrae than was necessary or accurate. This was most noticeable in one of his most well-known pieces La Grande Odalisque, which he had submitted to the Salon before leaving for Rome, and which he later found out to be highly criticized at its debut exhibition.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres – A Master of Neoclassicism.” Art in Context. September 5, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/jean-auguste-dominique-ingres/

Meyer, I. (2022, 5 September). Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres – A Master of Neoclassicism. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/jean-auguste-dominique-ingres/

Meyer, Isabella. “Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres – A Master of Neoclassicism.” Art in Context, September 5, 2022. https://artincontext.org/jean-auguste-dominique-ingres/.