René Magritte – Belgium’s Witty Reality-Defying Surrealist

Belgian surrealist artist René Magritte is the most renowned artist from his country of the previous century. But what is René Magritte best known for and how did he achieve such popularity? René Magritte’s paintings belong to the surreal space art genre, such as his most well-known piece The Son of Man (1964). In this article, we will explore René Magritte’s biography and art, from his canvases through to Magritte the artist’s surreal photography.

René Magritte’s Biography and Artworks

René Magritte has received widespread appreciation for his unique contribution to Surrealism. To sustain himself, he worked as a professional designer for many years, creating commercial and book graphics, which very certainly influenced his fine art, which frequently has the shortened effect of a commercial.

While other Surrealists from France lived showy lifestyles, Magritte favored the calm obscurity of a middle-class lifestyle, as indicated by the bowler-hatted individuals who frequently appear in his work.

In subsequent periods, he was chastised by his colleagues for some of his techniques (such as his proclivity to make several reproductions of his photographs), but his popularity has only grown since his passing. Theoretical artists loved his utilization of text in pictures, and artists in the 1980s appreciated some of his later work for its confrontational aesthetic.

| Date Born | 21 November 1898 |

| Date Died | 15 August 1967 |

| Place Born | Brussels, Belgium |

| Associated Movements | Surrealism |

Early Life of René Magritte

René Magritte was born in Lessines, Hainaut province, Belgium, in 1898. He was the eldest of three brothers born into a middle-class household. His father is known to have worked in manufacturing, while his mother was a dressmaker prior to her marriage. Magritte’s growth as an artist was inspired by two key incidents in his boyhood. The first was a chance contact with a painter working in a graveyard, whom he came across while exploring with a friend.

“I discovered, in the center of some fractured stone pillars and heaped-up foliage, an artist who had traveled from the city, and who looked to me to be practicing sorcery”, Magritte later recounted.

His mother ended her own life by drowning herself on the 12th of March, 1912 in the Sambre River. This was not her only try at suicide; she had attempted others over the years, prompting Léopold, her husband, to confine her to her room. She fled one day and became absent for several days. Her remains were eventually located about a mile down a neighboring river.

According to lore, young Magritte was there when her remains were recovered from the ocean, but new evidence has debunked this tale, which may have started with the family caregiver. When his mother was discovered, her garment was allegedly concealing her face, a sight that has been proposed as the inspiration for numerous of Magritte’s paintings from 1927 until 1928 of individuals with material hiding their heads, notably Les Amants (1928).

Artistic Career of René Magritte

Magritte wished to establish a technique free of the stylistic diversions that characterize much contemporary art. While several French Surrealists explored new methods, Magritte decided on a dry, illustrated style that clearly communicated the subject of his images.

Magritte used recurrence as a method to inspire not just his treatment of themes within single paintings, but also to encourage him to make many reproductions of some of his finest pieces.

Early Period

Magritte began painting in 1915 and was accepted into the Académie des Beaux-Arts in Brussels the succeeding year. However, he was underwhelmed by his lessons, and as a consequence, his participation decreased. He became good friends with another pupil, Victor Servranckx, who exposed him to Cubism, Futurism, and Purism.

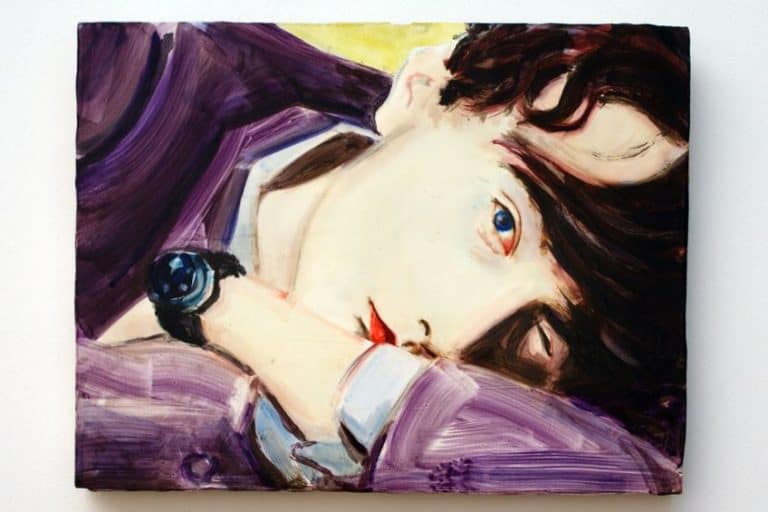

Magritte was particularly captivated by the oeuvre of Fernand Leger and Jean Metzinger, who both have had a significant effect on Magritte’s initial studies, as seen by his attempts with Cubism, including his painting Bather (1925). Magritte’s early works, dating from around 1915, were in the Impressionistic manner. Gisbert Combaz, an artist and graphic designer, also taught him at the Académie Royale.

Mature Period

Magritte served his mandatory military duty in 1921 before returning home in 1922 to wed Georgette Berger, a woman he had known since adolescence. He also started working as a draftsman at a wallpaper business under Servranckx’s direction. This position lasted approximately a year, following which Magritte became a freelancing billboard and advertising designer. He got a deal with the Galerie le Centaure in Brussels in 1926 and was capable of making a livelihood as a fine artist for a short time. Magritte’s work underwent significant alterations throughout this early time.

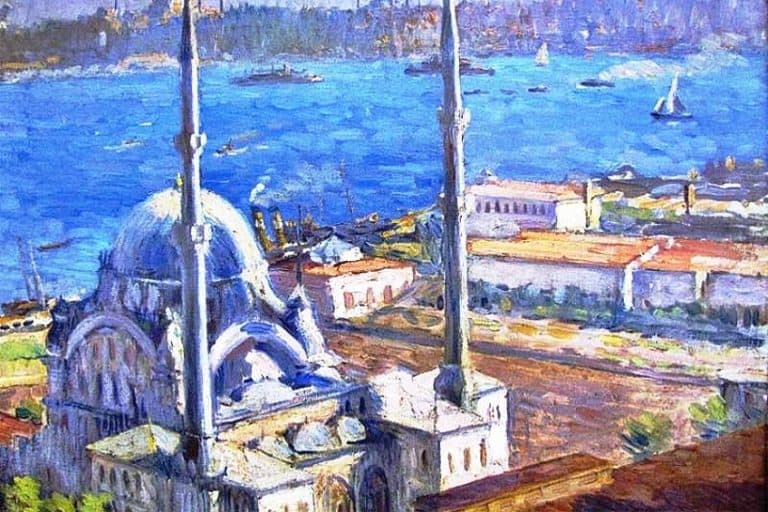

Around 1925, he became acquainted with Giorgio de Chirico’s oeuvre and started to operate more clearly inside the Surrealist style.

Not only were René Magritte’s paintings from the mid-1920s evocative of the bleak and enigmatic moods established by de Chirico’s works, but the young artist actually went so far as to transfer several of de Chirico’s favorite items such as orbs, locomotives, and plaster figures onto his own paintings. The Song of Love (1914) by Giorgio de Chirico moved Magritte to tears, which he characterized as “one of the most touching experiences of my life: my eyes beheld thinking for the very first time.”

Magritte created his first surreal work, The Lost Jockey, in 1926, and staged his first solo show in Brussels the following year. The exhibition was slammed by reviewers. Frustrated by his failure, he relocated to Paris, where he met André Breton and then became active with the Surrealist movement.

Magritte’s brand of Surrealism has an illusionistic, fantastical aspect to it.

Magritte stayed in Paris from 1927 to 1930, where he became close to André Breton’s group of Parisian Surrealists, which also included painters such as Salvador Dali and Max Ernst. He began infusing more obscurely organic shapes into his works, as well as working with typically Surrealist subject material like lunacy and insanity. Nevertheless, Magritte became more disenchanted with his contemporary Surrealists’ “dark” topics. Maybe most importantly, it would be in Paris that he began to explore the employment of words and language in his works.

Magritte’s contractual revenue ended when Galerie Le Centaure shut at the conclusion of 1929. Magritte went to Brussels in 1930, having already made little of an impression in Paris, and continued working in marketing. He and his sibling, Paul, established an organization that provided him with a decent salary. Magritte entered the Communist Party in 1932, and he would quit and return to it multiple times over the next several years.

Scholars debate whether Magritte augmented his earnings during this period by manufacturing forgeries of known artists’ works and maybe counterfeit cash. Nevertheless, Magritte had little time to dedicate to his own paintings from 1930 until 1937.

His first solo exhibit in the United States was in New York in 1936 at the Julien Levy Gallery, succeeded in 1938 by a show at the London Gallery. Throughout his early years, Magritte was able to live rent-free at the household of English surrealist supporter Edward James in London, where he researched construction and produced. James appears in two of Magritte’s 1937 paintings, La Reproduction Interdite and Le Principe du Plaisir.

Late Period

Throughout the German invasion of Belgium during WWII, he stayed in Brussels, resulting in a schism with Breton. As a response to his emotions of isolation and desertion as a result of residing in German-occupied Belgium, he temporarily embraced a bright painting technique from 1943 until 1944 a phase dubbed his “Renoir era.” He penned, “The Nazis accomplished far more effectively the impression of disorder, of fear, that Surrealism intended to cultivate in order to throw it all into doubt. In response to overwhelming negativity, I now suggest a quest for pleasure and fulfillment.”

In 1946, abandoning the brutality and gloom of his previous works, he signed the statement “Surrealism in Full Sunlight” with numerous other Belgian artists.

During his “Vache era,” from 1947 until 1948 Magritte worked in a confrontational and vulgar Fauve manner. He created a deliberately offensive “barbaric” style known as “vache“, which was marked by filthy topics and harsh colors and is widely recognized as a spoof of the Fauves. Paintings such as High Level Meetings (Les Grands Rendez-vous) and Philosophy in the Bedroom are examples of his “vache” style artworks. Magritte’s paintings in this manner were widely disliked, as he had predicted.

During this era, Magritte sustained himself by producing phony Braques, Picassos, and de Chiricos—a deceptive repertory that he would later extend into the manufacture of falsified banknotes during the bleak postwar years. This enterprise was performed in collaboration with his brother Paul and colleague Surrealist and “substitute son” Marcel Marin, to which the responsibility of marketing the counterfeit had fallen.

Magritte reverted to the form and topics of his pre-war surrealism work around the end of 1948.

Magritte was a political leftist who remained sympathetic to the Communist Party even after the war. Yet, he was skeptical of the Communist left’s formalist policy, arguing that “class politics is as essential as bread; but it does not imply that laborers must be confined to water and bread and that desiring chicken and wine would be detrimental.” While staying dedicated to the liberal left, he campaigned for artistic individuality. Magritte was an agnostic spiritually. Magritte’s work sparked a surge in popularity in the 1960s, and his iconography has impacted pop, minimalism, and conceptualism.

Personal Life of the Belgian Surrealist Artist

In June 1922, Magritte wedded Georgette Berger. Georgette, the child of a butcher, met Magritte when she was only 13 and he was around the age of 15. They reconnected in Brussels seven years later in 1920, when Georgette, who had also pursued painting, became Magritte’s figure, inspiration, and eventually wife. Magritte’s relationship was strained in 1936 when he encountered and started a relationship with a female performing artist named Sheila Legge.

Magritte planned for his acquaintance, Paul Colinet, to amuse and divert Georgette, but this resulted in Georgette and Colinet having an affair. Magritte and his spouse reconciled only in 1940. Magritte succumbed to pancreatic cancer on the 15th of August, 1967, at the age of 68, and was laid to rest in Schaerbeek Cemetery.

Legacy of Magritte the Artist

René Magritte’s intriguing investigation of the capriciousness of pictures has had a significant effect on modern artists. Ed Ruscha, John Baldessari, Andy Warhol, Jan Verdoodt, Jasper Johns, Martin Kippenberger, Storm Thorgerson, Duane Michals, and Luis Rey are among the artists who have been affected by Magritte’s paintings. Some of the artist’s pieces have clear connections, while others provide modern perspectives on his abstract fascinations.

The use of basic visual and everyday images by Magritte has been compared to those of pop artists. While Magritte himself denied the link, his effect on the evolution of pop art has been universally acknowledged.

He saw pop artists’ depictions of “the universe as it is” as “their mistake,” and compared their focus on the transient with his interest for “the sense for the genuine, in as much as it is enduring.” The 1960s saw a surge in popular interest in Magritte’s art. His paintings have been regularly reproduced or pirated in ads, posters, book covers, and the like due to his “sound grasp of how to show items in a manner both provocative and challenging.”

The main heroine Hazel Grace Lancaster in John Green’s fictitious novel (2012) and film (2014) The Fault in Our Stars wears a tee shirt with Magritte’s The Treachery of Images. Just before departing her mother to meet her favorite writer, Hazel discusses the painting to her befuddled mother and mentions that the author’s work contains “many Magritte allusions,” evidently hoping the author would appreciate the connection.

René Magritte’s paintings had a significant effect on a variety of trends that emerged after his death, including Conceptualism, Pop, and 1980s painting. His artwork, notably, was regarded as a forerunner of forthcoming art movements due to its concentration on the idea over technique, tight link with commercial art, and attention to ordinary things that were frequently duplicated in pictorial space.

It’s obvious as to why creators like Martin Kippenberger, Andy Warhol, and Robert Gober consider Magritte to be a major influence.

The Style of René Magritte the Artist

Magritte’s artworks usually depict a group of everyday objects in an odd environment, giving recognizable objects new significance. The use of items as something other than what they appear to be is exemplified in his picture The Treachery of Images (1929), which depicts a pipe that appears to be modeling for a nicotine store promotion. Magritte wrote beneath the pipe, “This is not a pipe,” which appears to be a paradox, but is really correct: the artwork is not a pipe, but rather an impression of a pipe. It does not “gratify emotionally”—when asked about this picture, Magritte said, “Obviously, it’s not a pipe, simply attempt to fill it with tobacco.”

In a picture of an apple, The Listening Room (1952), Magritte took the very same strategy: he depicted the item and then utilized an inner subtitle or frame technique to deny that the object was a fruit. Magritte emphasizes in these “Ceci n’est pas” pieces that despite how rationally we describe an item, we never capture the thing itself. Amongst Magritte’s paintings are surrealist adaptations of other renowned works, such as Perspective I (1963) and Perspective II (1950), which is a copy of Manet’s The Balcony (1868), but with human beings substituted with tombs.

Elsewhere, Magritte confronts the issue of conveying meaning through artwork with a repeating image of an easel, such as in his The Promenades of Euclid (1955) or The Human Condition series (1935), wherein the towers of a fortress are “painted” upon the mundane streets that the canvas views. He stated of the latter work in correspondence to André Breton that it didn’t matter if the view behind the easel changed from what was shown on it, “but the key issue was to eradicate the distinction between a perspective viewed from the outside and from on the inside of a room.” Some of these images have thick curtains framing the windows, implying a theatrical theme.

Magritte’s artworks of Surrealism are more figurative than the “automatic” manner of painters like Joan Miró.

Magritte’s utilization of everyday things in unusual settings is linked to his goal to generate poetic images. He characterized the act of creating as follows: “the skill of juxtaposing colors in such a manner that their true feature is obscured, so that known objects—sky, humans, plants, hills, furnishings, constellations, solid constructions, street art merged in a single artistically disciplined picture This image’s poetry is devoid of any symbolic value, old or modern.”

René Magritte’s surreal space art was defined as “evident visuals that hide naught; they generate wonder and, certainly, when one views one of my works, one wonders, ‘What does that really mean?’ It has no meaning because enigma has no meaning since it is unknown.”

Magritte’s continual experiment with truth and perception has been ascribed to his mother’s untimely mortality. Psychologists who studied grieving children claimed that Magritte’s to and fro play with fact and fantasy reflected his “continuous moving between what he desires, ie: his mother still being alive to his mother has passed on.”

Magritte intended to demonstrate an attitude that was free of the aesthetic impediments that distinguish much modernist artwork. Magritte decided on a somber, illustrated tone that effectively communicated the subject of his images, while several French Surrealists experimented with new methods. His interest in the concept may have sprung in part from Freudian psychoanalysis, which considers repetition to be a symptom of trauma.

However, his employment in the world of commercial painting may have prompted him to challenge the usual modernist concept in the unique, original piece of art. Magritte used repetition as a method to inspire not just his handling of themes within individual paintings, but also to encourage him to make many copies of some of his finest works.

For English subtitles, simply click on “Settings”, followed by “Subtitles/CC”, and then click on “Auto-translate”. You can select your language of choice from the list provided.

The pictorial nature of Magritte’s paintings frequently results in a tremendous dichotomy: visuals that are lovely in their purity and clarity, yet can elicit disturbing feelings. They appear to proclaim that they conceal no enigma, yet they are also fantastically weird. As Magritte historian David Sylvester so eloquently put it, his works evoke “the type of wonder felt during an eclipse. Magritte was interested in the interconnections between linguistic and visual messages, and some of his most renowned paintings combine the two.

While such images frequently share the aura of mystery that defines most of his Surrealist work, they also appear to be inspired by a sense of intellectual inquiry – and amazement – at the errors that might lie in words.

Men with bowler hats, which figure often in Magritte’s paintings, might be regarded as self-portraits. Characterizations of the artist’s spouse, Georgette, and views of the couple’s humble Brussels flat are also prevalent in his works. Although this may imply personal material in Magritte’s paintings, it is more probable to relate to the everyday origins of his inspirations. It’s as if he felt that we didn’t need to search far for the strange, since it lurked everywhere, even in the most mundane of lives.

Exhibitions and Collections

The Magritte Museum in Brussels opened up to the public on the 30th of May, 2009. It is situated in the neo-classical five-story Hotel Altenloh and exhibits 200 authentic Magritte paintings, sketches, and sculptures, notably Scheherazade, The Return, and The Empire of Light. This multimodal continuous exhibit has the world’s largest Magritte collection, with the majority of the works coming straight from Magritte’s widow, and his principal patron, Irene Hamoir Scutenaire.

Magritte’s studies with surreal photography from 1920 onwards, as well as his short Surrealist films from 1956 onwards, are also on display in the museum.

Another museum is housed in Magritte’s previous residence at 135 Rue Esseghem in Brussels, where he resided with his spouse from 1930 until 1954. Olympia (1948), a naked picture of Magritte’s wife reputedly valued over US$1.1 million, was taken from this institution by two men with guns on the 24th of September, 2009. In January 2012, it was surrendered to the museum in return for a 50,000-Euro payout from the institution’s insurance. The burglars apparently agreed to the bargain since they couldn’t sell the artwork on the illicit market because of its popularity.

The Menil Collection located in Houston, Texas, houses one of the most important galleries of surrealist art in the U.S, featuring dozens of René Magritte oil canvases, gouaches, sketches, and sculptures.

The Eternally Obvious (1930), The Meaning of Night (1927), The Rape (1934), Golconda (1953), and The Listening Room (1952) are among the major oil paintings in the Menil Collection, which are normally displayed a handful at a time on a rotational schedule with other surrealist pieces in the selection.

Magritte’s art has been featured in many retrospective exhibits in France, most lately at the Centre Georges Pompidou (from 2016 until 2017). His artwork has been included in three retrospective exhibits in the United States: at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (2013), the Museum of Modern Art (1965), the Metropolitan Museum of Art (1992). In 2018, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art had a show named The Fifth Season that concentrated on his later career.

Notable Artworks

René Magritte was quite a prolific artist. He created a large body of surreal space art and surreal photography throughout his lifetime. Let us look at some of his most notable works.

- Landscape (1920)

- Sixth Nocturne (1923)

- The Bather (1925)

- The Lost Jockey (1926)

- The Enchanted Pose (1927)

- The Treachery of Images (1929)

- The Universe Unmasked (1932)

- The Human Condition (1933)

- The Rape (1934)

- The Future of Statues (1937)

- The Break in the Clouds (1941)

- The Good Omens (1944)

- Personal Values (1952)

- The Fountain of Youth (1957)

- The Golden Legend (1958)

- The Memoirs of a Saint (1960)

Recommended Reading

Belgian surrealist artist Magritte is well known for how amazing surreal space art is. René Magritte’s biography is full of interesting details that cannot all be fit into a single article. If you are interested in learning more about Magritte’s artworks and life, then you may wish to read one of the many wonderful books written about Magritte the artist. Therefore, we have recommended a book on that very subject.

René Magritte: The Fifth Season (2018) by Caitlin Haskell

Something unforeseen happened to René Magritte while he was in his forties. Between 1926 and 1938, the artist cultivated a distinctive Surrealist style, but then began producing paintings that appeared nothing like his previous works. He began with an Impressionist style, copying Renoir’s soft, dreamy palette, which he called “sunlit Surrealism.” Then he changed his approach again, adding popular iconography, the loud colors of Fauvism, and the expressive brushstrokes of Expressionism. Then, as though nothing had occurred, Magritte reverted to his original manner.

René Magritte: The Fifth Season examines Magritte’s work during and after the 1940s artistic crises, illustrating his changed views about art. The creator’s Renoir era, as well as his Fauvist and Expressionist genre works of art that are not recognized by American audiences, are investigated in this book, as are the hypertrophy of artifacts works of art, a sequence that tries to play with the magnitude of common objects, and the mysterious Dominion of Light suite, works of art that indicate the concurrent encounter of night and day.

That wraps up our look at the fascinating and surreal space art of Magritte the artist. Belgian surrealist artist René Magritte is the most renowned artist from his country of the previous century. René Magritte’s paintings belong to the surreal space art genre, such as his most well-known piece “The Son of Man” (1964). Magritte’s art influenced a number of genres that evolved after his death, including Conceptualism, Pop, and 1980s painting. His artwork, in particular, was recognized as a harbinger of upcoming art trends owing to its emphasis on concept over technique, close relationship with commercial art, and attention to everyday objects that were frequently repeated in visual space.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is René Magritte Best Known For?

René Magritte was the most globally recognized surrealist painter of all time, but it wasn’t until he was in his 50s that he was able to achieve some kind of success and recognition for his work. Rene Magritte defined his works as follows: “My paintings are visual images that hide absolutely nothing; they generate enigma, so when one encounters one of my works, one just asks oneself, ‘What does it all really mean?’ It has no meaning since mystery has no meaning and is unknown.”

How Does One Describe Magritte’s Artworks?

René Magritte created surreal space art and surreal photography. He had a funny and irreverent sense of humor, which functioned in many of his paintings and became some of his most well-known compositions all through the duration of his career. He developed a series of pipe paintings as an illustration of this. When examining the complete series as a cohesive piece, rather than seeing the photographs individually, you can plainly see his preoccupation with a contradictory reality.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “René Magritte – Belgium’s Witty Reality-Defying Surrealist.” Art in Context. February 9, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/rene-magritte/

Meyer, I. (2022, 9 February). René Magritte – Belgium’s Witty Reality-Defying Surrealist. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/rene-magritte/

Meyer, Isabella. “René Magritte – Belgium’s Witty Reality-Defying Surrealist.” Art in Context, February 9, 2022. https://artincontext.org/rene-magritte/.