When Was the First Camera Invented? – History of the Camera

When was the first camera made, and do we know who made the first cameras? The camera’s invention was seen as a major breakthrough in technology at its time. The first camera ever made was not even used for photography, but for artists to trace scenes from the world around them! Let’s find out more about the world’s first camera, and answer your related questions, such as, “when was the first camera invented, and what was the first camera?”.

When Was the First Camera Invented?

Cameras, as we know them today, look very different from how they looked a few decades ago. It is quite likely that many of today’s younger generation have only ever used the camera that is built into their phones. However, not too long ago, the only way to take a photograph was with a dedicated device, ranging from cheap, disposable cameras to top-of-the-line professional equipment. But, what was the first camera ever made in human history?

As we mentioned before, the first camera did not take photographs but rather projected an image onto a surface.

The World’s First Camera

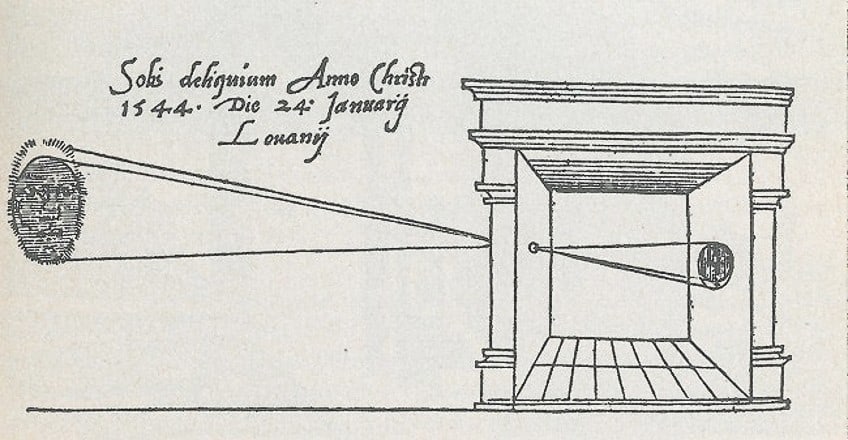

The camera obscura was the predecessor to the conventional photographic camera. The optical phenomenon which is naturally observable is known as camera obscura and takes place when a particular image of a scene located on one side of a wall is projected through a small hole in that wall producing an inverted image on a surface located on the other side of the opening. The earliest recorded reference to this principle is by Mozi, the Han Chinese philosopher. He was correct when he suggested that the image in the camera obscura was inverted because light flows in straight lines from the point of origin.

The application of a lens in a wall opening of a darkened room for projecting images for the purposes of drawing dates back to around 1550.

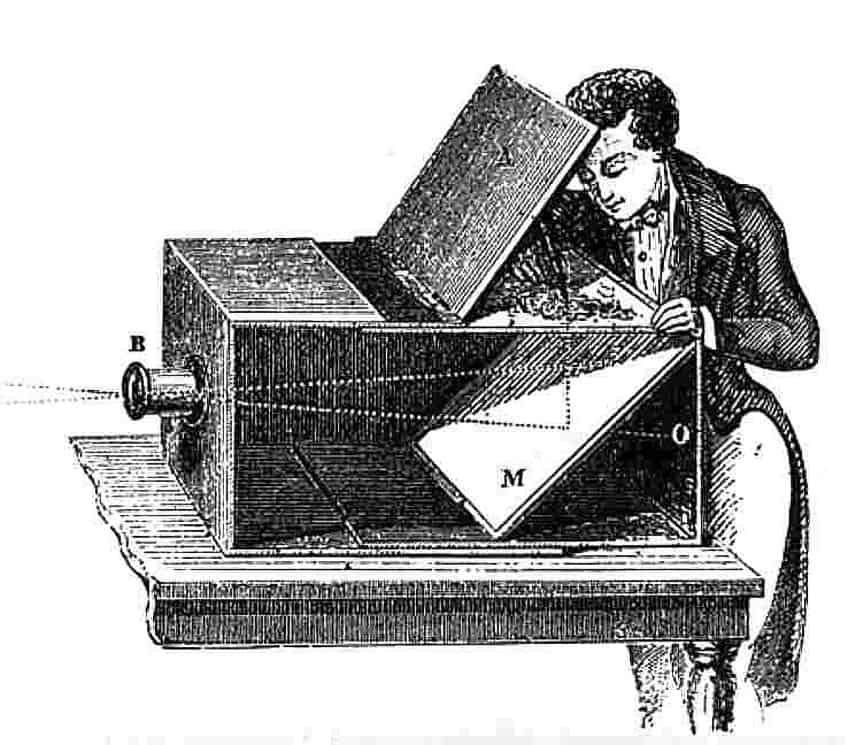

Portable camera obscura setups in boxes and tents have been used as drawing tools since the late 17th century. There was no way of preserving the images created by these cameras prior to the advent of photography techniques other than physically tracing them. The first cameras were large, having enough room to fit one or more individuals inside; but these progressively evolved into smaller and smaller formats. A portable camera Obscura that was appropriate for photography was easy to obtain by Niépce’s time. Johann Zahn envisaged the first camera compact and portable enough to be used for photographic purposes in 1685, but it would be nearly one and a half centuries before such an application became a reality.

Origins of the Camera Obscura

The first camera’s invention can be traced back to the efforts of Ibn al-Haytham, who is recognized as the inventor of the pinhole camera. While the results of a single light going through a pinhole had previously been identified, Ibn al-Haytham provided the first scientifically accurate study of the camera obscura. He was the first person to utilize a screen in a darkened space to project an image from one side onto a screen placed on the other side. It also featured the first quantitative and geometrical descriptions.

Through Latin translations, Ibn al-Haytam’s literature on the topic of optics became immensely influential all across Europe, inspiring individuals like Leonardo da Vinci, John Peckham, Witelo, Johannes Kepler, and René Descartes.

The First Photographic Cameras

For centuries prior to the invention of the photographic camera, it had been observed that certain compounds, such as silver salts, became darker when subjected to the light from the sun. In 1777, Swedish chemist, Carl Wilhelm Scheele, demonstrated that silver chloride was particularly susceptible to fading from exposure to light, and he found that once it darkened, it was rendered insoluble in an ammonia solution. Thomas Wedgwood was the first to use this chemistry to produce images. Wedgwood created his images by placing things like insect wings and foliage on ceramic pots treated with silver nitrate and exposing the set-up to sunlight. These images, however, were not permanent because Wedgwood did not use a fixing technique. He ultimately did not succeed in his attempt to use this method to create permanent images with a camera obscura.

The Photographic Camera’s Invention

In 1826, Joseph Nicéphore Niépce took the first permanently fixed photograph of a camera image with a sliding wooden box camera constructed by Vincent and Charles Chevalier in Paris. Since 1816, Niépce had experimented with techniques to improve the images that could be produced with a camera obscura. Niépce’s successful image depicts the scenery from his window. It was created using an 8-hour exposure on bitumen-coated pewter. Niépce coined the term “heliography” in reference to his method. Niépce spoke with Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre, an inventor, and the two collaborated to further develop the heliographic method.

Niépce continued to experiment with various chemicals in order to enhance the contrast in these heliographs. Daguerre refined the camera obscura’s design, but the collaboration stopped when Niépce passed away in 1833.

Daguerre achieved a high-contrast, razor-sharp image by exposing it on a silver iodide-coated plate and then exposing it once again to mercury vapor. Daguerre was able to make these images permanent using an ordinary salt solution by 1837. He dubbed these Daguerreotypes and unsuccessfully attempted to commercialize them for several years. The French government subsequently obtained Daguerre’s technique for public dissemination, thanks to the assistance of politician and scientist, François Arago. In return, Daguerre and Niépce’s son, Isidore, were given pensions.

Further Developments

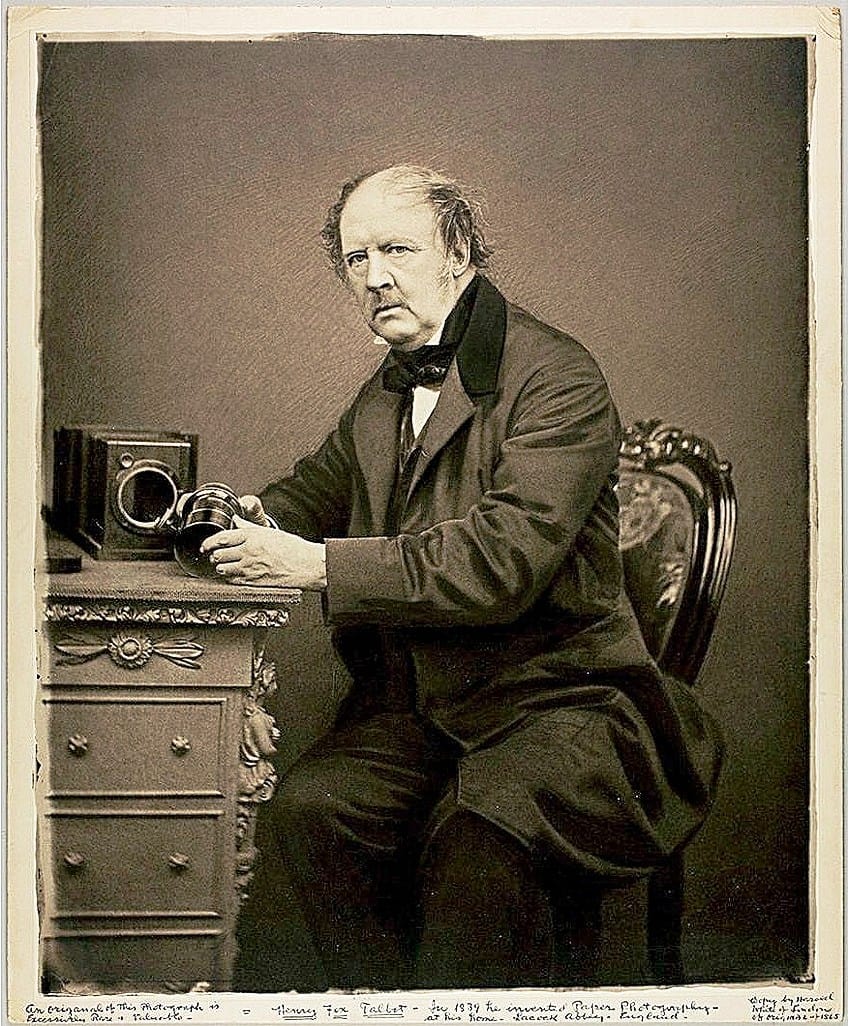

The English physicist William Henry Fox Talbot independently created a method for capturing images with silver salts in the 1830s. Despite his disappointment that Daguerre had introduced photography to the public before him, he presented a pamphlet to the Royal Institution on the 31st of January 1839, which was the first printed overview of photography. Talbot created calotypes within two years, a two-step procedure for generating photos on paper. The calotype method was the first to use negative printing, whereby all values are reversed in the reproduction process – white appears as black and vice versa.

Negative printing allows for the creation of an infinite number of positive prints from a single negative. The Calotype method also gave printmakers the option of changing the image by touching up the negative. Calotypes never rose to the popularity of daguerreotypes, owing primarily to the latter’s clearer details. Duplicates are not possible with daguerreotypes because they only generate a direct positive print. The two-step negative/positive technique is the foundation of modern photography.

The First Camera Ever Made for Commercial Use

Alphonse Giroux built the first photographic camera produced for commercial use, a daguerreotype camera, in 1839. Giroux agreed to manufacture the cameras in France with Isidore Niépce and Daguerre, with each box and accompanying accessories costing 400 francs. The camera featured a two-box design, with an outer box housing a landscape lens and an interior box housing a focusing screen and image plate. Objects at varying ranges could be brought into clearer focus by sliding the inner box in or out. The screen was then substituted with a sensitized plate when a good image had been attained on the screen. A copper flap that acted as a shutter was controlled by a knurled wheel in front of the lens.

Long exposure durations were required for early daguerreotype cameras, which could range from 5 to 30 minutes in 1839.

More Manufacturers Join the Trend

Other manufacturers immediately made better variations after the launch of the Giroux daguerreotype camera. In 1841, Charles Chevalier, who had previously supplied Niépce with lenses, invented the double-box version that used a half-sized plate for its imaging. The hinged bed on Chevalier’s camera collapsed halfway onto the back of the nested box. Along with improved mobility, the camera had a quicker lens that cut exposure times to around 3 minutes and featured a specialized prism in front of the camera’s lens that allowed for improved lateral accuracy in the image. Marc Antoine Gaudin developed another French design in 1841. On the front of the lens of the Nouvel Appareil Gaudin type of camera was a metallic disc that featured three different-sized holes.

Changing the hole gave variable f-stops, enabling various amounts of light to enter the camera. Gaudin’s camera used nested brass tubes for focussing instead of nested boxes. Peter Friedrich Voigtländer created an all-metal device with a unique conical shape that generated circular images about 3 inches in diameter in Germany. The Voigtländer camera was distinguished by its use of Joseph Petzval-designed lenses. The Petzval lens was over 30 times faster than any other lens available at the time, and it was the first to be designed exclusively for portraiture. Until Carl Zeiss created the anastigmat lens in 1889, it was the most extensively used design for portrait photography.

The Arrival of Photographic Film

George Eastman pioneered the use of photographic film, first with paper film in 1885 before transitioning to celluloid in 1889. Eastman’s very first camera, dubbed the “Kodak”, was released commercially in 1888. It was a basic box camera with a single shutter speed that appealed to the common consumer due to its inexpensive price. It was pre-loaded with sufficient film for 100 images and then had to subsequently be returned to the camera factory for further processing and reloading. By the close of the 19th century, Eastman’s product line had grown to include both folding and box cameras. He advanced mass-market photography with the introduction of the Brownie, a very basic and low-cost box camera that pioneered the notion of the snapshot. It was a huge hit, and numerous varieties were still available well into the 1960s.

The introduction of film also enabled the movie camera to progress from an expensive hobby to a useful commercial device.

Despite Eastman’s success in producing low-cost photography devices, plate cameras delivered higher-quality prints and were still prevalent well into the 20th century. To compete with roll-film cameras, which allowed more exposures per loading, many cheaper plate cameras from this time period were outfitted with magazines that could hold numerous plates at once. Plate camera backs that allowed them to use film packs were also offered, as were roll-film camera backs that allowed them to utilize plates. Apart from a few exceptions, such as Schmidt cameras, the majority of professional astrographs used plates until the end of the 20th century, after which electronic photography took its place.

The First Video Camera

Historians generally agree that the very first movie camera was invented by William Kennedy Laurie Dickson. Yet, as we will see, this is a warped version of the narrative, as many brilliant brains raced to create a workable movie camera during this golden era of inventions. Dickson, a Scottish inventor, worked for Thomas Edison in the late 1880s. He invented the Kinetograph, which employed an electric motor to spin a sprocket wheel with a film strip within. The sprocket spun after revealing a frame to expose the following frame. The film strip was then projected to display a succession of images on a screen. While the majority of historians attribute the invention of the movie camera to Dickson, the present-day movie camera is based on the work of multiple 19th-century inventors. Soon after the photographic camera was invented, inventors all around the world set out to design the first moving picture camera.

The Race for the First Video Camera

The chronophotographic gun was designed in 1882 by Étienne-Jules Marey, a scientist from France. It had a metal shutter and could shoot 12 photos per second on a plate. Wordsworth Donisthorpe had patented the Kinesigraph camera, which could collect and project a succession of images, two years before the Kinetograph. Donisthorpe was born in Leeds, which was also the birthplace of Louis Le Prince. Louis Le Prince had already submitted for an American patent in 1886 for 16 lenses capable of capturing and projecting moving images. The patent was issued in 1888, although not for one or two-lens cameras. Louis Le Prince inexplicably vanished in 1890, triggering theories ranging from assassination plots to suicide owing to financial difficulties.

Alexander Parkes’ invention of celluloid film led to the invention of the motion picture camera that William Friese-Greene, a British inventor patented in 1889.

On the 17th of October, 1888, Edison submitted a caveat to the Patents Office in order to protect his new invention. Kazimierz Proszynski, a Polish inventor, created the Pleograph in 1894, which is another early prototype for a motion picture camera. The Pleograph was a camera and projector in one. A few years later, Proszynski developed the first camera that worked with compressed air, the Aeroscope. The first movie cameras were made by these distinct inventors, and by the end of the 19th century, camera companies were producing movie cameras for the general public.

The Arrival of Color Film

The earliest color photography methods appeared in the 1890s. They replicated the effects of color by combining blue, green, and red light, as demonstrated by James Clerk Maxwell in the 1860s. They are referred to as ‘additive’ color techniques. The American inventor, Frederic Ives, invented a process that was based on three color-separation negatives taken through colored filters. Positive transparencies were then subsequently created from these negatives and inserted into a special device called a Kromskop. The images were placed on the three transparencies using mirrors, and the colors were restored using an additional set of filters. The generated images, known as kromograms, were effective but excessively expensive, and Ives’ technique was ultimately too sophisticated to be commercially successful.

The Joly Process

Rather than taking three separate exposures with green, red, and blue filters, a simpler solution was to take only one exposure with a filter that included all three basic colors. Dr. John Joly of Dublin invented the first technique that used this technology in 1894. Joly created a three-colored filter screen by adding very fine green, red, and blue lines on a glass plate. The screen would then be placed in front of the camera’s plate when taking a photo. The positive black-and-white image was carefully placed in register with yet another filter screen after exposure and reverse processing. The end result was a color transparency that could be seen through transmitted light. The Joly method commercially debuted in 1895 and lasted on the market for a few years.

However, because of the plates’ poor color sensitivity, the resulting images were not always successful.

The Autochrome Process

Louis and Auguste Lumière, two French brothers, devised the first commercially viable screen technique, autochrome, early in the 20th century. They had been dabbling with color photography since the 1890s and wrote their first article on the topic in 1895 – the same year they became renowned for inventing the Cinématographe. They first presented their method of production to the French Academy of Science in 1904, and by 1907, they were commercially producing autochrome plates. The news of their discovery quickly spread, and samples of the new plates were in high demand. The critical response was ecstatic. Realizing there was no need to separate the filter screen from the photographic emulsion, the Lumières integrated the two on the same glass substrate.

Cameras in the 1920s

The emergence of inexpensive cameras and improved photographic processes made photography more accessible to the general public in the 1920s. The company Leica was the first to develop a 35mm camera, the Leica I, in 1925. The type of film used in this camera was 35mm, which was substantially smaller than the previously prevalent format films. Cameras were more portable as a result, allowing for more unplanned and candid photographs. Several manufacturers started producing small cameras that were both economical and simple to operate in the 1920s. The Kodak Brownie and the Agfa Billy were two popular models. Cameras started to have more complicated aperture controls and shutter mechanisms in the 1920s, offering better control over exposure settings. From 1927 to the early 1950s, Agfa created a line of folding cameras known as the Agfa Billy. These cameras were famous for their unusual design.

They had a sleek, streamlined body composed of metal or leatherette-covered cardboard, with colorful embellishments on occasion.

The Agfa Billy cameras were quite popular at the time because of their affordable price and simplicity of use. They were targeted towards amateur photographers looking for a basic camera for capturing snapshots and pictures of their families. Rollei launched the first TLR camera in 1929, with two lenses – one for seeing and one for shooting images. This approach allows for better compositional control and precision.

The First Digital Camera

Eugene F. Lally, who worked at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory of Nasa, first came up with the idea of a digital camera in 1961. When Lally wasn’t focusing on artificial gravity, he was contemplating how astronauts could find out their position in space by taking images of the stars and planets with a mosaic photosensor. Lally did figure out how to fix the red eye in images, but his idea of digital photography was still years ahead of the technology available at that time. Around 10 years Willis Adcock, a Texas Instruments employee, had the same ideas for a filmless camera. The digital camera, however, did not come to fruition until 15 years later.

Sasson’s First Proper Digital Camera

Steven Sasson, an engineer from Eastman Kodak created the first digital camera in 1975. He constructed a prototype using a movie camera lens, a few Motorola parts, 16 batteries, and newly designed electronic sensors. The resulting camera weighed over 4 kg and was about the same size as a printer. It recorded black-and-white images on digital cassette tapes, and Sasson and his colleagues had to create a unique screen to view them. The prototype from Kodak had an image quality of 0.01 megapixels. The first digital photograph was taken in 23 seconds. Some argue that Kodak blew its future potential by not further working on this technological breakthrough because it preferred to focus on photographic film.

As a result, the following stage in the process of creating a viable digital camera would come from somewhere else.

Developments in the 1980s

By the 1980s, handheld cameras had abandoned film. Sony first presented a prototype Magnetic Video Camera device in 1981. It wasn’t, however, strictly a digital camera. The Mavica was actually a television camera that took still images. These cameras were forerunners of digital cameras because they recorded images on electronic mediums while still recording analog data. In 1986, Canon released the first analog electronic camera for sale. Nevertheless, due to poor image quality and expensive costs, these types of cameras never truly took off. Because of their ability to transmit photos, they were mostly employed by newspapers to cover events.

In 1981, the first digital camera that really worked was produced.

The Fairchild All-Sky camera was created to capture images of auroras in the sky by the University of Calgary Canada ASI Science Team. The Fuji DS-1P was supposed to be the first genuinely portable digital camera in 1988. It saved photos as computer files on a 16MB SRAM internal memory card created in collaboration with Toshiba, however, the DS-1P was never made commercially available. The very first digital camera to be sold in the country was actually the Dycam Model 1 from 1990. In 1988, the MPEG and JPEG standards for digital picture and audio files were developed.

That brings us to the end of this exploration of the history and development of cameras. As we have discovered, cameras were actually invented way before photographic film was even thought of! From its humble beginnings as a tracing device for artists, it arose over time to become far more influential than even art in the modern era. Over time, the materials and processes changed, allowing for progressively clearer images and more affordable equipment – from hazy and indistinct black and white images, through color photography, all the way to the ultra-clean high-resolution images we enjoy in the digital era today!

Frequently Asked Questions

When Was the First Camera Invented?

The very first camera did not use any sort of film and was called the Camera Obscura. The idea had actually been around for centuries, but did not begin to fully develop into practical devices until much later when they were able to eventually produce permanent images using a process called Heliography. In 1826, Joseph Nicéphore Niépce took the first permanently fixed photograph ever documented.

When Was the First Camera Made and Who Made the First Cameras?

Louis Daguerre developed the first camera in France in 1839, which was commercially produced. It involved a kind of photographic process that generated a single image on a polished silver plate that needed several minutes of exposure time. Different kinds of cameras and photographic processes were created soon after the daguerreotype was introduced. The wet plate collodion process was invented in the 1850s, allowing for faster exposure times and making photography a viable option for everyday usage. However, because this procedure required a portable darkroom, photography remained rather challenging for the average person.

What Was the First Camera Available to the Market?

The Daguerreotype camera was the first commercially available camera. A highly-polished silver plate that had been covered with silver iodide was employed in the camera. Photographers all across the world immediately adopted the Daguerreotype method, which contributed to transforming the art of photography.

Jordan Anthony is a film photographer, curator, and arts writer based in Cape Town, South Africa. Anthony schooled in Durban and graduated from the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, with a Bachelor of Art in Fine Arts. During her studies, she explored additional electives in archaeology and psychology, while focusing on themes such as healing, identity, dreams, and intuitive creation in her Contemporary art practice. She has since worked and collaborated with various professionals in the local art industry, including the KZNSA Gallery in Durban (with Strauss & Co.), Turbine Art Fair (via overheard in the gallery), and the Wits Art Museum.

Anthony’s interests include subjects and themes related to philosophy, memory, and esotericism. Her personal photography archive traces her exploration of film through abstract manipulations of color, portraiture, candid photography, and urban landscapes. Her favorite art movements include Surrealism and Fluxus, as well as art produced by ancient civilizations. Anthony’s earliest encounters with art began in childhood with a book on Salvador Dalí and imagery from old recipe books, medical books, and religious literature. She also enjoys the allure of found objects, brown noise, and constellations.

Learn more about Jordan Anthony and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Jordan, Anthony, “When Was the First Camera Invented? – History of the Camera.” Art in Context. July 12, 2023. URL: https://artincontext.org/when-was-the-first-camera-invented/

Anthony, J. (2023, 12 July). When Was the First Camera Invented? – History of the Camera. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/when-was-the-first-camera-invented/

Anthony, Jordan. “When Was the First Camera Invented? – History of the Camera.” Art in Context, July 12, 2023. https://artincontext.org/when-was-the-first-camera-invented/.