Early Christian Art – Christian Artwork and Biblical Paintings

The scriptures have for many centuries been a source of inspiration for Christian painters and sculptors. They have influenced great artists in many eras, leaving behind masterful examples of Medieval Christian art and religious Renaissance art for us to explore and enjoy. Let us take a deeper look at the history of Christian artwork, Christian sculpture, and famous biblical paintings.

A Brief History of Early Christian Art

Tracing the early days of Christian artwork can be a difficult task to undertake. Before 100 CE, Christians were a persecuted minority, so the chances of them being allowed to create art at this time were rather slim. At that time, Christianity was a small fringe religion with very few followers and little to no public recognition or support, so Christian painters would not have had the luxury of financial support from patrons.

It was also forbidden to create idols, so this too could have influenced the lack of art before 100 CE. Historians and scholars have divided Early Christian art into two distinct periods: Before 313 CE and after 313 CE, as this was the year of the Edict of Malan.

Let us now explore the various periods of early Christian artwork and Christian sculptures.

Symbolism in Early Christian Art

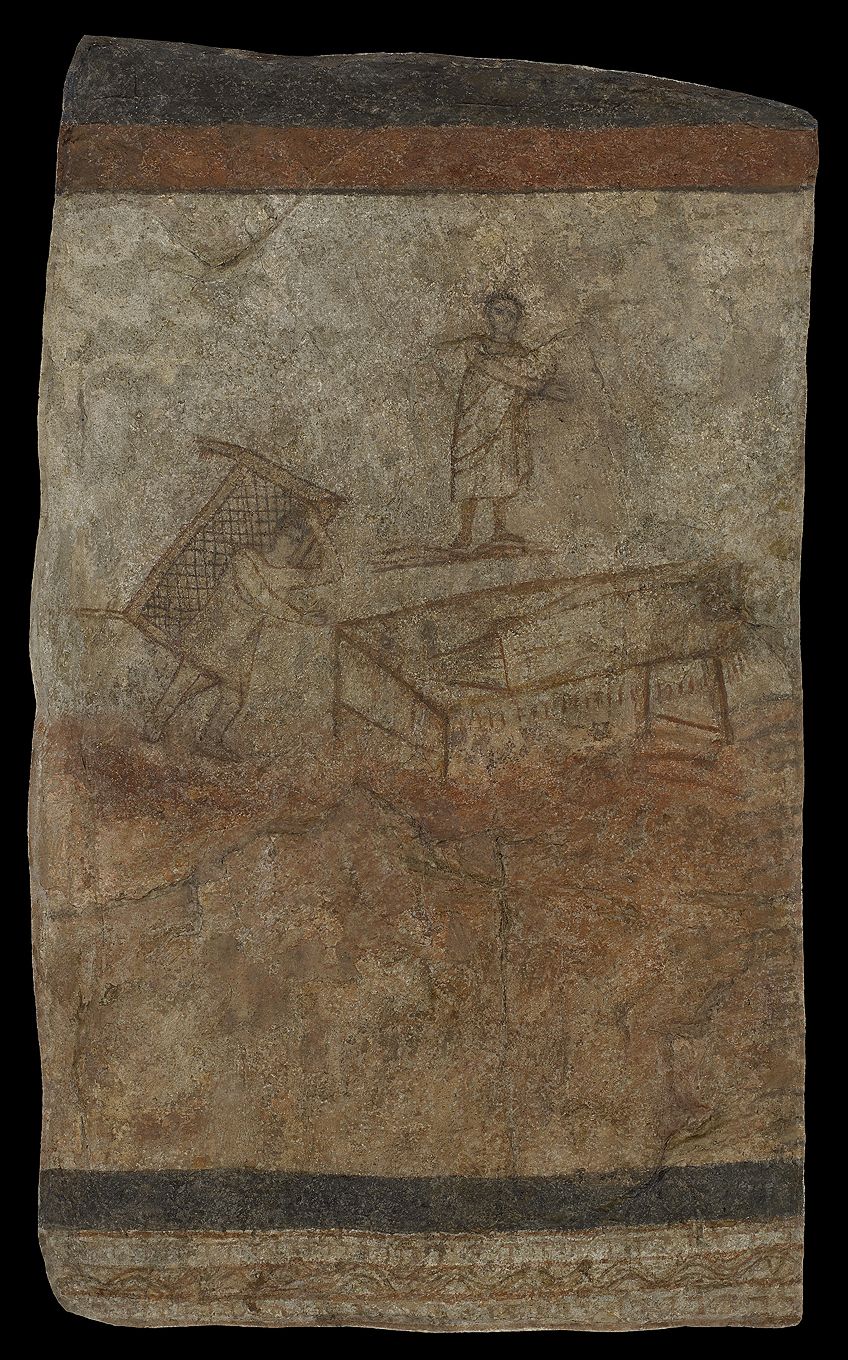

Under the Roman Empire in the earliest days of Christianity, Christian artwork was intentionally ambiguous so that the Christian undertones could not be noticed by the eyes of the Roman oppressors. They incorporated Christian themes subtly into imagery that was accepted within the predominantly Pagan culture. The first examples of Christian art still surviving today were found in the catacombs of Rome, on surfaces in Christian burial tombs, dated to be from somewhere between the 2nd to 4th centuries.

To hide the meaning of these early Christian artworks, artists represented the figure of Jesus symbolically with pictogram symbols such as the peacock, lamb, fish, or anchor.

The symbol of the cross was not used to represent Jesus until many centuries later, as in the early days of Christianity, crucifixion was a common form of punishment for various offenses and therefore would not have been exclusively linked with Christianity, but rather with incivility.

Another symbol often used to represent Christ was the symbol of unity and peace, the dove.

Early Christian Art Before 313 CE

Besides the early Roman occupation discrimination against Christianity and Christian art, several other possible factors could have resulted in a lack of art representing Christian figures. The people of that time were influenced by several different theologies and philosophies; some believed that God could be experienced directly, others thought he couldn’t, and others thought that if he could, then he should not be physically depicted.

Modern historians have suggested that it was perhaps the prominent belief at the time that it was simply not possible to perceive the divine, let alone recreate it.

Historians also suggest that perhaps the main reason Christian art does not exist in the earliest days of the religion is that the majority of folk were poor and did not own any property. Once the economic situation improved for them, they were able to afford to indulge in hobbies such as Christian paintings, Christian sculptures, and Christian architecture.

The Dura-Europos church is considered to be the oldest church still in good condition, and it has been dated between the periods 230 CE to 256 CE. This building was originally a house that was later converted into a church, and in it, there are biblical paintings on the walls, including images of Jesus as both the shepherd and the Christ. The catacombs of Rome were created a few decades before the Dura-Europos church, however, these earliest examples of Christian art only depicted praying as opposed to the actual image of Jesus seen later in the Church house.

Stylistically, these early Christian paintings that adorned the walls of the catacombs were very similar to other catacombs of many other religious groups, including the Roman mystery religions, paganism, or those that belonged to members of the Jewish faith. Compared to the art of the rich, these paintings were relatively low in quality but depicted a charming expressiveness of the figures.

Early Christian art from this period often created “abbreviated” scenes, where well-known religious incidents were represented by one to four figures.

This fitted in with the Roman style of compartmentalizing the art in the room with various geometric layouts. A popular subject at this time was the representation of biblical figures being rescued from mortal danger in some way, such as biblical paintings depicting the Sacrifice of Isaac, Noah kneeling in prayer in the ark, the resurrection of Jesus, and Jonah and the Whale.

Christian sculptures from this period are very rare and mostly small in stature. Common motifs such as the Good Shepherd were prevalent as it was a symbolic figure found in many religions and therefore not strictly associated with Christian artwork. There were, however, about 270 small figurines unearthed in modern Turkey, and some of these represent patently Christian iconography such as Jonah and the Whale.

By the end of the pre-Constantinian period, the portrayal of Jesus in Christian art had become accepted and fully developed.

Typical scenes from this period depict various stories from the New Testament, as well as depictions of the passion of Christ. Many variations of his image were depicted at this time, from a beardless and short-haired stocky fellow to the long-haired, thin-faced figure that has since become the most commonly adopted portrayal of Jesus.

Early Christian Art After 313 CE

Emperor Constantine defeated Mexnethius in 312 CE, after which he became the main patron of Christianity, transforming the religious landscape and the associated buildings dramatically. After he granted religious tolerance to Romans in 313 CE with the Edict of Milan, Rome changed towards an increasingly Christian territory. It was the responsibility of the reigning emperor to create places of worship for his subjects, and these temples reflected the provincial religious faith at the time of his reign. It was no different for Constantine and Christianity.

The small and discreet buildings usually used for religious worship soon proved to be too small after Christianity experienced an explosion in growth.

Many pagan temples were still used by their original followers, and in some places like Rome, Christians refused to attend worship there until they were converted to churches in the 6th and 7th centuries. Many temples were unsuitable for transition to Christian adaptation as pagans mostly used their windowless temples for the storage of religious objects and worshipped outside.

Thus, Constantine set about constructing churches such as the Church of St. Peter in Rome, the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem, as well as many churches in the newly named capital city of Constantinople.

A major challenge that faced the architects was deciding on a new layout and form for religious worship, as the previous designs were created for a different functionality than the Christian method of indoor communion. These new churches needed to be large to house the ever-growing Christian fellowship and to make a visible distinction between the faithless and the faithful.

Based on these factors, it was decided to incorporate the architectural form of the basilica and adorn it appropriately with rich religious symbolism and artwork.

Basilicas were not new and had been built centuries previously for use as extensions to palaces, public meeting halls, or courts of law. These courts usually had a judge presiding from a chair situated at the end of the hall in a semi-circular dome overlooking the hall. This imposing aesthetic carried over from court of law to place of worship, to the priest standing at his altar.

Importance of the Christian Church

Once Christianity had been legalized as a religion, the styles of Christian art began to expand even more. As more Christian churches were constructed, and most of the public (both rich and poor) adopted Christianity, the type of art that was present in the churches became more distinguished to suit its surroundings and worshippers.

The influence of the Christian church on the art of this time was great, as more complicated and extravagant artworks were commissioned to artists, as seen by the surviving frescos and mosaics from this period.

Naturally, the dominant theme that was seen within Christian art was Christianity, with many sacred images from the religion being depicted in the numerous artworks that were produced. During the Medieval period, the Christian church dominated every aspect of society’s lives. All individuals, regardless of their status, vehemently believed in the existence of God, Heaven, and Hell, and that the only way to enter Heaven was to abide by the rules of the Roman Catholic church.

Since its starting point throughout the first century of the Roman Empire, Christianity immediately began to spread around the world. Thus, over time, the Christian church quickly became the biggest and most powerful benefactor of the arts, as many paintings and sculptures were commissioned for the inside of churches.

This meant that the subject matter in these artworks focused solely on religion, as one of the aims was to create an identity for the religion and to draw in parishioners.

Resurrection of Christ

One of the most commonly depicted themes that have been fundamental to the Christian religion and in Christian art is the resurrection of Christ. Whether portrayed as part of a series of works or in a single instance, the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus exists as the most integral component of Christianity and makes up the majority of the artworks found in churches.

Through different periods, the theme of resurrection has been explored and displayed in a variety of ways, as each art period had influence on the artworks that were created.

Mosaic Art

An art form that proved to be incredibly popular during the early Christian art period, and more hard-wearing than traditional fresco paintings, was mosaic art. This type of art formed a crucial part of early Christian art, however, our knowledge surrounding mosaic art is somewhat limited as only certain artworks have survived from the first half of the 4th century.

As Christianity became an official religion of the Roman empire at the start of the 4th century, grand Christian basilicas were scheduled to be constructed.

Within these new places of worship, artworks were needed to adorn the walls and ceilings. Thus, magnificent and opulent glass-colored mosaics were used, which quickly became very popular. The four main basilicas of Rome were said to “shine like Heaven on Earth” thanks to their use of mosaics, with some of these mosaics still seen today if you visit them.

The use of mosaic in art attested to the sheer strength of Christianity during this time, as it was an extremely expensive and delicate material to work with.

The early Christian basilicas that were adorned with mosaic art demonstrated the strong influence of Christianity over society, with these stunning basilicas reminding us of that power even today. In the late 16th century, an official Vatican mosaic workshop was established in the Vatican City to pay homage to this art form, and still exists today.

Religious Renaissance Art

During the 13th and 14th centuries, churches became massive patrons of Christian art and commissioned and bought large quantities of work from Christian painters. Many members of the public were unable to write at this time, so art was used to help them envision the scriptures, creating a sense of respect and awe amongst the community. Churches hoped to use the art to create a deeper connection with their followers, hoping that the scenes of salvation and damnation would inspire or terrify them into being more devoted.

Christian artists from the Early Renaissance started adding a touch of realism to their art, making the figures look more true to life and the settings more natural and realistic.

By doing so, they hoped to draw the viewer into the artwork and empathize more with the subjects and subject matter by recognizing themselves in the faces and settings of the paintings. Throughout this period, artists continued to refine their processes, becoming ever more influential on the masses and simultaneously influenced by the masses.

During this period, church elders were continuously stressing the humanity of Jesus and how the congregation should be leading their lives using his as an example. Therefore, the artwork of this time depicts a Jesus that portrays human frailties and suffering, as well as divinity and themes connected to images of his birth and death. Both of these periods of Christ’s life convey aspects of Christian belief that are a fundamental part of the doctrine, being the concepts of incarnation and resurrection.

Let us now look at a few examples of religious Renaissance art.

Madonna and Child (c. 1300) by Duccio di Buoninsegna

| Artist | Duccio di Buoninsegna |

| Year | c. 1300 |

| Medium | Tempera |

| Where It Is Currently Housed | Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City |

Duccio di Buoninsegna was an extremely influential Renaissance artist of the early 14th century, and his version of the Madonna and child is thought to have been painted sometime around the year 1300. Compared to larger versions of the Madonna and child found in churches and altars, this painting is comparatively small and was most likely created to be a personal image for devotional use.

The painting’s use for devotional purposes can be hinted at by the burnt edges, most likely obtained from the use of candles at a small altar at its base.

Despite the simplistic nature of the composition, this artwork marks a departure from the Byzantine era’s use of less detailed iconic images, and the attempt to move closer to portraying images likely to create an emotional connection between the viewer and the art piece.

These aspects of humanism can be seen in the artist’s use of emotive human gestures between the mother and the child sitting on her lap, as well as the detailed garments.

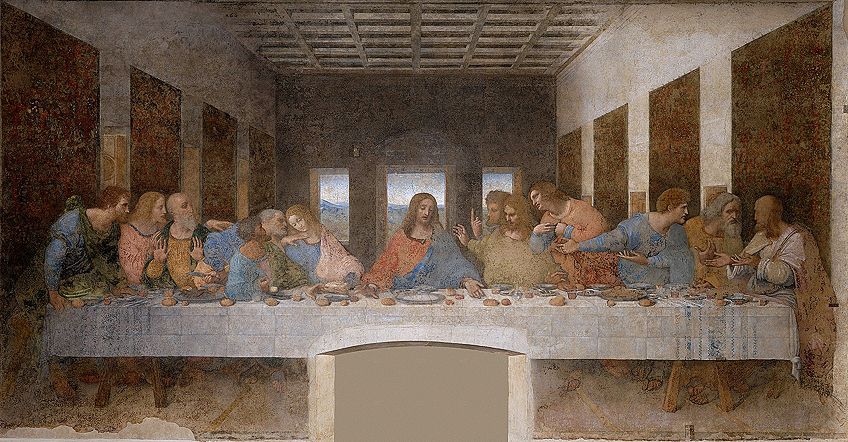

The Last Supper (c. 1495) by Leonardo da Vinci

| Artist | Leonardo da Vinci |

| Year | c. 1495 – 1498 |

| Medium | Tempera on gesso, pitch, and mastic |

| Where It Is Currently Housed | Santa Maria delle Grazie, Milan |

Possibly one of the world’s most easily recognized paintings, Leonard da Vinci painted The Last Supper in the late 15th century. Housed in the Covenant of Santa Maria Delle Grazie in Milan, da Vinci started work on the painting around 1495 as part of a commissioned job to renovate the church by his patron the Duke of Milan, Ludovico Sforza.

As the name suggests, the painting depicts the scene of Christ’s last dinner with his apostles.

Da Vinci has tried to capture the moment of consternation among his followers as he announces that one of the apostles would eventually betray him. Each apostle is depicted with a different reaction to his revelation, all displaying varying degrees of shock, anger, and disbelief. As was common with other paintings of the last supper from that era, da Vinci has positioned all the apostles at one side of the table so that none of them have their backs facing the viewer. Most other versions of this scene have Judas placed on the other end of the table away from all the apostles, but in his rendition, Leonardo placed Judas in the shadows.

Despite many attempts at restoration throughout the years, very little of the original painting still exists.

When Sforza renovated the church, his builders used moisture-retaining rubble to fill the walls, which resulted in the paint being unable to get a decent grip on the walls from the start. The painting already began to show signs of deterioration shortly after it was finished. Two copies of The Last Supper have been found that were made by da Vinci’s assistants before the final one was painted. One is now housed at the Royal Academy of Arts and the other is housed at the Church of St. Ambrogio in Switzerland.

The Creation of Adam (1512) by Michelangelo

| Artist | Michelangelo |

| Year | c. 1512 |

| Medium | Fresco |

| Where It Is Currently Housed | Sistine Chapel, Vatican City |

Michelangelo painted this famous fresco from 1508 until 1512, and it forms part of the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. Considered one of the most famous biblical paintings in the world, it depicts the moment God gave life to Adam.

Michelangelo was originally commissioned to paint the twelve apostles on the sides that support the ceiling, but he managed to convince Pope Julius to give him free artistic reign, suggesting a far more complex scheme than initially devised.

Centering around the nine chapters from the Book of Genesis, the composition contains over 300 various figures and stretches over 500 square meters. It is segmented into three parts: the creation of the earth, the creation of humankind, and the fall from the grace of God. God is portrayed as an old, gray-haired white man cloaked in a swirling robe. Adam is depicted without any clothing and is reclining on the ground.

God’s right arm is outstretched with his index finger reaching to touch Adam’s finger, thereby bestowing life upon him. Adam’s left arm is stretched out, a mirror image of the pose of God, a symbolic reflection that man was made in the image of God. Much debate has arisen as to the identities of the twelve figures surrounding God.

It is now widely accepted that the female under God’s right arm represents Eve and that the other figures represent the children of Eve, the human race.

The Tower of Babel (1563) by Pieter Bruegel the Elder

| Artist | Pieter Bruegel the Elder |

| Year | c. 1563 |

| Medium | Oil on wood panel |

| Where It Is Currently Housed | Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna |

Pieter Bruegel the Elder created three different paintings with the Tower of Babel as its subject matter. The first was painted in Rome and was a miniature created on ivory. The other two are the only surviving works that aren’t lost to time. They are referred to as the “Great” Tower and the “Little” tower. Both of these were painted on wood panels using oil paint.

One is now housed at the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, and the other at the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen in Rotterdam.

The painting housed in Rotterdam is approximately half the size of the other one. Although they are based on the same subject and contain the same basic compositions, once one takes a closer look, it becomes evident that all the details vary greatly, from the landscape to the sky to the vastly different-looking tower.

This artwork portrays the building of the Tower of Babylon, a story from the Book of Genesis in which humanity unifies and creates a building that can reach the heavens in celebration of their achievements. This portrayal of the Tower of Babylon contains architecture that is notably Roman.

Apparently, this was done intentionally to reflect the Christian disdain for Roman rule. Artists in this period were known to constantly draw parallels between Babylonian and Roman societies.

Notable Early Christian Artworks

From Medieval Christian art through to the Renaissance period, Christain artwork has been created in many different mediums such as paintings on canvas and murals on walls to Christian sculptures and architecture. Let us take a look at some notable examples of early Christian artworks.

Sarcophagus of Junius Bassus

| Artist | Unknown |

| Year | 359 AD |

| Medium | Marble |

| Where It Is Currently Housed | Museo Storico del Tesoro della Basilica di San Pietro, Vatican City |

This early Christian sarcophagus was made around 359 CE for the burial of Junius Bassus and is made from marble. It is considered the most famous of Christian sculptures and was originally placed under Old St. Peter’s Basilica until its rediscovery in 1597. It is now housed under the Saint Peter’s Basilica Museum in the Vatican. The detailed iconography embraces imagery from the old and new Testaments, along with the Dogmatic Sarcophagus.

This Christian sculpture is one of the oldest surviving sarcophagi of this quality and status.

The sarcophagus’s owner, Junius Bassus, was a senator in charge of the capital who died at the early age of 42. As Bassus was a high-ranking official, it was believed that someone couldn’t be both a senator and pious Christian. However, it is said that he converted to Christianity on his deathbed. The carvings are on three sides of the sarcophagus, allowing it to be displayed and positioned against a wall. The Anatolian style of arranging reliefs in columnar frameworks can be seen applied to this art piece.

Various scenes are depicted on this sarcophagus such as the sacrifice of Isaac, the trial of Jesus, a depiction of Adam and Eve, and the judgment of Peter.

Basilica of Sant’Apollinare Nuovo

| Artist | Bishop Ursicinus |

| Year | 6th century |

| Medium | Bricks |

| Where It Is Currently Housed | Ravenna, Italy |

The Church of Sant’Apollinare in Classe was originally built and designed by Arian Theodoric as his palace chapel. As part of an attempt to suppress all references to his beliefs, the Catholic Church reconsecrated the Basilica in 561 CE. This included the reworking of the mosaic art he had created.

When the artifacts of Saint Apollinaris were transferred there in 856 CE, it became known as the Basilica of Saint Apollinaris.

Of much interest to scholars are the mosaic works depicting the miracles and teachings of Christ, which have luckily survived regardless of the modernization and considerable renovation of the basilica over the years. Of particular interest to historians and scholars is the first appearance of the Devil in the history of art; to the left of Jesus appears a red angel situated behind three goats.

The Basilica of Sant’Apollinare Nuovo is a UNESCO World Heritage site and is regarded as one of the most crucially important sites of Medieval Christian art in Europe. This is chiefly due to the mixture of Eastern and Western Christianity motifs, as shown by the Eastern Orthodox (bearded) and Western Orthodox (non-bearded) versions of Christ.

Moses Striking the Rock (1624) by Joachim Anthonisz Wtewael

| Artist | Joachim Anthonisz Wtewael |

| Year | 1624 |

| Medium | Oil on panel |

| Where It Is Currently Housed | National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C. |

Moses striking the Rock was created in 1624 by Joachim Anthonisz Wtewael and typifies his lifelong association with and use of mannerism. Mannerists created artificial yet elegant scenes using elongated figures, alternating light, as well as dark patterns and contorted poses. This artwork portrays the moment that God enabled Moses to lead the Israelites out of the land of Egypt, as told in the Book of Exodus.

Surrounded by the children, women, and animals, Moses strikes the rock with the very same rod that he had previously used to part the Red Sea.

This story had particular meaning to the artist and other Dutch people as they were able to draw parallels between their fight for independence from the Spanish and the biblical story. Moses was seen as a religious allegory of their own leader, Prince William of Orange, who was the hero of the Dutch Revolt, and like Moses, did not live to see his promised land.

Wtewael was an ardent supporter of Orange, and it is thought that his decision to paint the scene was done to help revitalize the public perception of the Prince to their version of Moses incarnate.

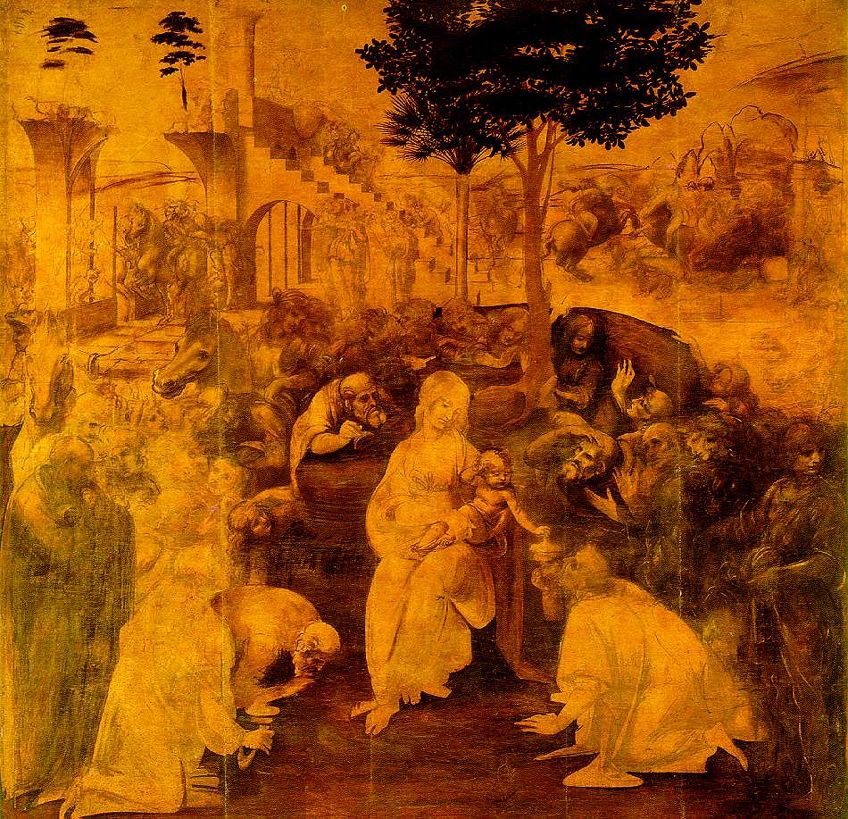

Adoration of the Magi (1481) by Leonardo da Vinci

| Artist | Leonardo da Vinci |

| Year | 1481 |

| Medium | Oil on wood |

| Where It Is Currently Housed | Uffizi Gallery, Florence |

Leonardo da Vinci was commissioned by the monks of San Donato in Florence to paint The Adoration of the Magi in 1481. He, however, departed for Milan the next year, leaving the painting incomplete. Since 1670, it has been housed at the Uffizi Gallery in Florence.

In this unfinished Christian artwork, da Vinci has portrayed the Virgin Mary and Child in the foreground, and the Magi kneeling at her feet in devotion with the figures all forming a triangular shape on the canvas.

In the background, a semicircle of people can be seen accompanying the virgin and child, one of which seems to be a self-portrait of da Vinci himself. On the left of the background are the ruins of a pagan building. Workmen can be seen carrying out repair works to sections of it. On the right of the scene is a rocky landscape and men fighting on horseback. It has been suggested that the ruins on the left are possibly a reference to the basilica of Maxentius.

It was part of Medieval legend that the basilica would stand until the miracle of a virgin birth.

The basilica was rumored to have suddenly collapsed on the night of the birth of Christ, but in truth, it would be many years before it was even built. The palm tree has been said to be a symbolic representation of both ancient Rome as well as Mary herself. This is due to the phrase from the Song of Solomon “you are as stately as a palm tree”. Its symbolism of Rome stems from the use of the palm tree to represent the triumph of good over evil, and the triumph over death.

Transfiguration (1516 – 1520) by Raphael

| Artist | Raphael |

| Year | 1516 – 1520 |

| Medium | Tempera on wood |

| Where It Is Currently Housed | Pinacoteca Vaticana, Vatican City |

Commissioned by Cardinal Giulio de Medici and created for the Narbonne Cathedral in France, this altarpiece was the last painting by Raphael, the Italian Renaissance master. He worked on it from 1516 until he died in 1520.

From the time of its creation until early in the 20th century, it was regarded as the most famous oil painting in the known world.

This artwork depicts two distinct biblical stories from the Gospel of Matthew. On the top half of the canvas is a depiction of the transfiguration of Christ as he radiates in glory, hovering above James, John, and Peter, who look on in wonder. On the lower half of the canvas, the apostles attempt and fail to exorcise demons from a child and eagerly await the return of Jesus. The arrival of Christ has resulted in the child being cured as he stands with his mouth agape and his arm raised towards the hovering Christ.

As his last work of art, Raphael created this artwork as his last testament to the miraculous ability of Christ to heal the sick. This final masterpiece is said to contain stylistic elements of both Baroque painting and the Mannerism movement. At its most basic level, the painting represents the dichotomy of the Divine nature of Christ contrasted with the struggles and flaws associated with mankind.

We have learned that Christian art was hidden in the early days due to the suppression of Christianity by the Roman Empire. It wasn’t until the rule of Constantine that things changed drastically, where Christianity became the religion ordained by the state and began to flourish. After that, Christian art could be found in temples, churches, and public areas. Since the early forbidden days of medieval Christian art through to the Renaissance, Christian art has experienced a colorful and epic journey of revival and survival. From the simplistic motifs on makeshift churches to the masterful frescos adorning the walls of chapels and cathedrals, Christian art has gone from underdog to overlord.

Take a look at our Christian artwork webstory here!

Frequently Asked Questions

Why Is It So Hard to Find Early Examples of Christian Art?

In the early days of the religion, most of the people who followed it were too poor to afford art supplies. Many of them also believed that God should not be depicted visually, and refrained from creating artwork that portrayed holy deities. Once Constantine changed the national landscape to one dominated by Christianity, churches started commissioning art and it became socially acceptable and financially viable for them to start creating Christian artwork. Before such a time as it became acceptable, artists had to carefully use symbolism to represent Christ and other Christian motifs in order to hide them from the Roman Empire. After the political and economic situation in the region improved, artists were able to start creating personal works of art that were free from persecution from the ruling stare.

What Subject Matter Did Early Christian Artists Paint?

As most works were commissioned by the churches, the majority of the subject matter was decided on by the clergy, although some artists were able to enjoy some free reign over what they could paint. The most common subject matter involved scenes of the birth and death of Christ, as well as scenes of creation such as the story of Adam and Eve, or even apocalyptic scenes. These paintings were created to simultaneously inspire the masses to devotion as well as instill the fear of hell, thus encouraging submission.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Early Christian Art – Christian Artwork and Biblical Paintings.” Art in Context. August 20, 2021. URL: https://artincontext.org/christian-art/

Meyer, I. (2021, 20 August). Early Christian Art – Christian Artwork and Biblical Paintings. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/christian-art/

Meyer, Isabella. “Early Christian Art – Christian Artwork and Biblical Paintings.” Art in Context, August 20, 2021. https://artincontext.org/christian-art/.