Dadaism – What Is the Meaning of the Meaninglessness of Dada Art?

Dadaism is one of the most unconventional and Avante-Garde art and cultural movements of the 20th century. Prompted by the European social climate following the First World War, Dadaism rejected wartime politics, bourgeois culture, and capitalist economic system. The name Dada has various meanings in different languages, but also no meaning. In essence, Dadaism offered nihilistic and anti-rationalist critiques of the status quo. Using non-traditional materials, nonsensical content, satire, and the fantastic, Dada artists turned the known into the unknown.

What Is Dadaism?

The first shoots of Dadaism sprung up in Switzerland during the First World War. As a neutral country, many artists and intellectuals who opposed the war sought refuge in Zürich. The movement arose as a reaction to the nationalism that many believed resulted in the war. The powerful influence of Dadaism spread quickly throughout Europe and the United States, with each city forming its own group.

Dadaism found influence in several other Avante-Garde movements of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. These movements include Futurism, Expressionism, Cubism, and Constructivism. A common thread that runs throughout these movements and Dadaism is that of cultural critique.

Dadaism was as untraditional in its output as it was in its material use. Works of Dada art range from photography to painting, sculpture, performance art, collage, and poetry. Through these works, Dada artists made a mockery of nationalist and materialist attitudes.

Although perhaps difficult to comprehend, Dadaism inspired many other artistic and cultural movements in the 20th century, including Surrealism, Abstract Expressionism, and even Punk Rock.

The Key Ideas of Dadaism

Defining Dadaism is a difficult task because, in a sense, it has no logical order or universally defining characteristics. So what is Dadaism? There are four key ideas that can help give insight into the Dadaism mind. These ideas include the use of readymades, the fascination with chance, the upending of bourgeois sensibilities, and the opposition of almost everything.

Dada artists created the readymade, an everyday object that they could buy, manipulate very little, and present as a work of art. The readymades bring to light one of the principal ideas of Dadaism, highlighting the artist’s intention as the artwork, as opposed to the object they create. We cannot appreciate the form or aesthetic of readymade works. Instead, these pieces prompt questions about the very definition of art, artistic creativity, and the purpose of art in society.

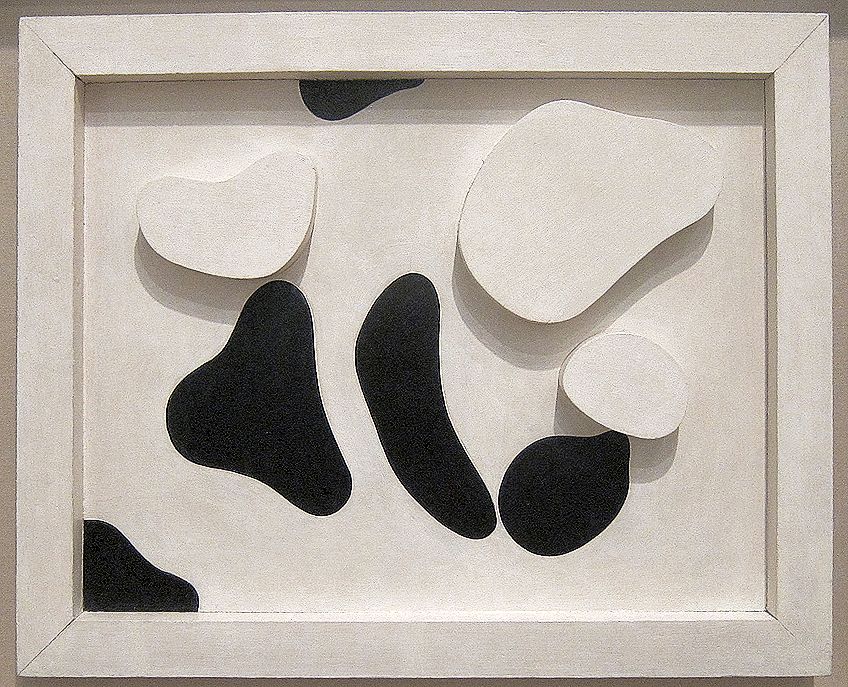

Another integral idea in Dadaism is the use of chance. Many Dada artists, including Hans Arp, created works of art by incorporating random chance. Creating without a plan or overarching intention worked against the grain of traditional art production. This artistic process was yet another way for Dada artists to challenge the status quo and question the artist’s place in creativity.

As we discuss some of the most famous works of Dada art, you will notice that much of it is not aesthetically pleasing. Artists were not concerned with creating works of art that appealed to social consciousness. Instead, Dada artists preferred to create artworks that upended the sensibilities of the bourgeois. Confronting artworks stimulated difficult questions about society and the purpose of art and the artist.

In fact, Dada artists were so intent on opposing all the norms and traditions of bourgeois society and culture that they were barely in favor of themselves. Many Dada artists would cry that even “Dada is anti-Dada.”

The founding place of Dadaism, in the Cabaret Voltaire, was appropriate in this sense. The French satirist, Voltaire, gave his name to the Cabaret from his novel that made fun of the idiocies of his society. Famous Dada artist Hugo Ball was a founder of Dada and the Cabaret, and he wrote that Dada was the Candide against the current times.

The Birth of Dadaism

The term Dada in colloquial French means “hobby horse”. It also means various other nonsensical things in other languages, but its meaning was of no interest to Dada artists. As a reaction to elements of the modern age, including the degradation of art and the capitalist culture. Dadaism is a form of anti-art, intending to draw attention and contemplation to the importance of art in society.

Switzerland, the birthplace of Dadaism, was neutral during the First World War and had limited censorship rules. In 1916, Emmy Hennings and Hugo Ball founded the Cabaret Voltaire on 5 February. Ball published a press release to attract other intellectuals and artists. A growing group of young writers and artists began forming under this name.

The group run by artists would attract guest artists to perform readings and musical entertainment at the daily meetings. Alongside Hennings and Ball, artists like Richard Huelsenbeck, Hans Arp, Marcel Janco, and Tristan Tzara were present from the beginning.

Ball read the first Dada manifesto on the first Dada evening in July of 1916. There is wide contention regarding the choice of the word Dada, but the most common origin story relates that Richard Huelsenbeck randomly plunged a knife into a dictionary.

Dada is reminiscent of the first words of a young child. With their keen interest in putting distance between the sobriety of conventional society and themselves, the group found this sense of childish absurdity appealing. The word Dada may also mean nothing or the same thing in all languages was vital for the frankly internationalist artists collective.

The groups’ intentions were twofold. Firstly, they wanted to help put an end to the war. The second aim of the Dada group was to challenge and express their frustrations towards the bourgeois and nationalist attitudes that they believed led to the war. The group was erratic in their organization, as their anti-authoritarian stance opposed any form of guiding ideology or group leadership.

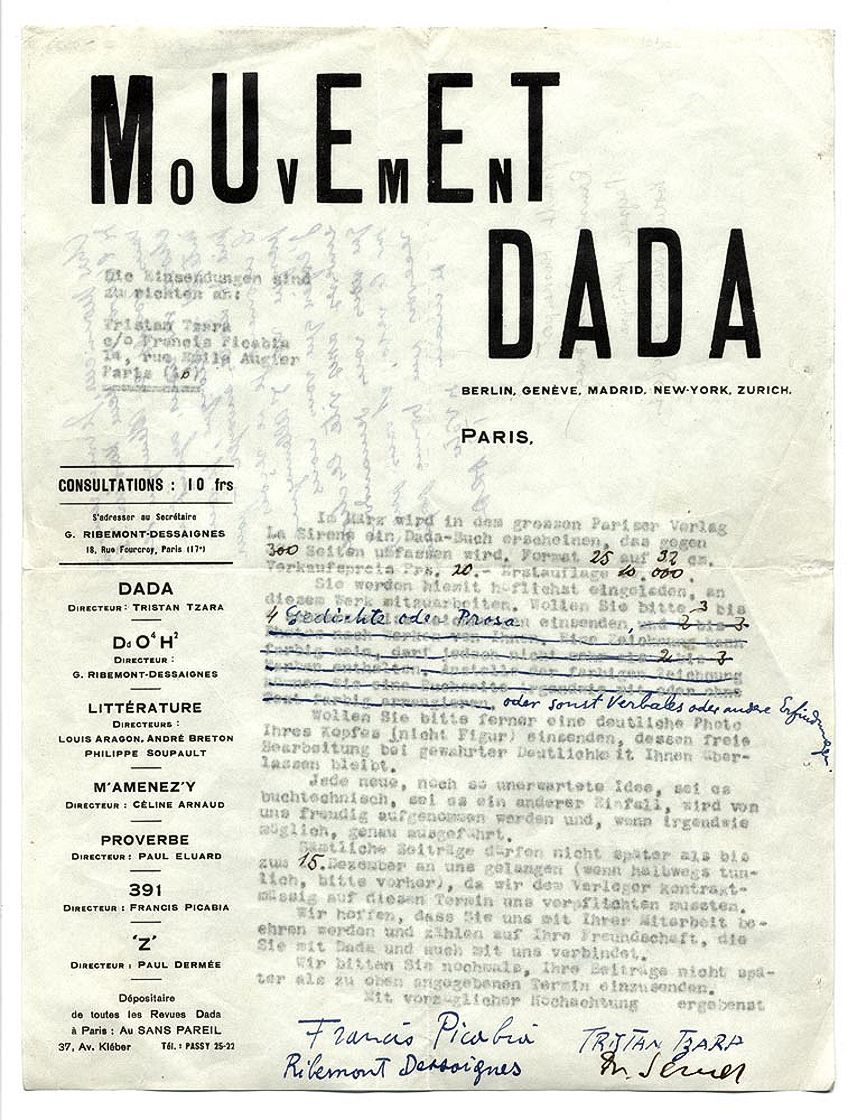

International Dadaism

At its heart, Dadaism was an international movement. In Zürich, Dada artists spread their anti-art and anti-war messages via exhibitions and the Dada magazine. Hugo Ball left Zürich in 1917 to pursue journalism, but Tristan Tzara facilitated further Dada evenings on Bahnhofstrasse at the Galerie Dada. As a result, Tzara became the leader of the movement, and he started a merciless crusade spreading the ideas of Dada throughout Europe. Part of the crusade was a torrent of letters written to Italian and French artists and writers.

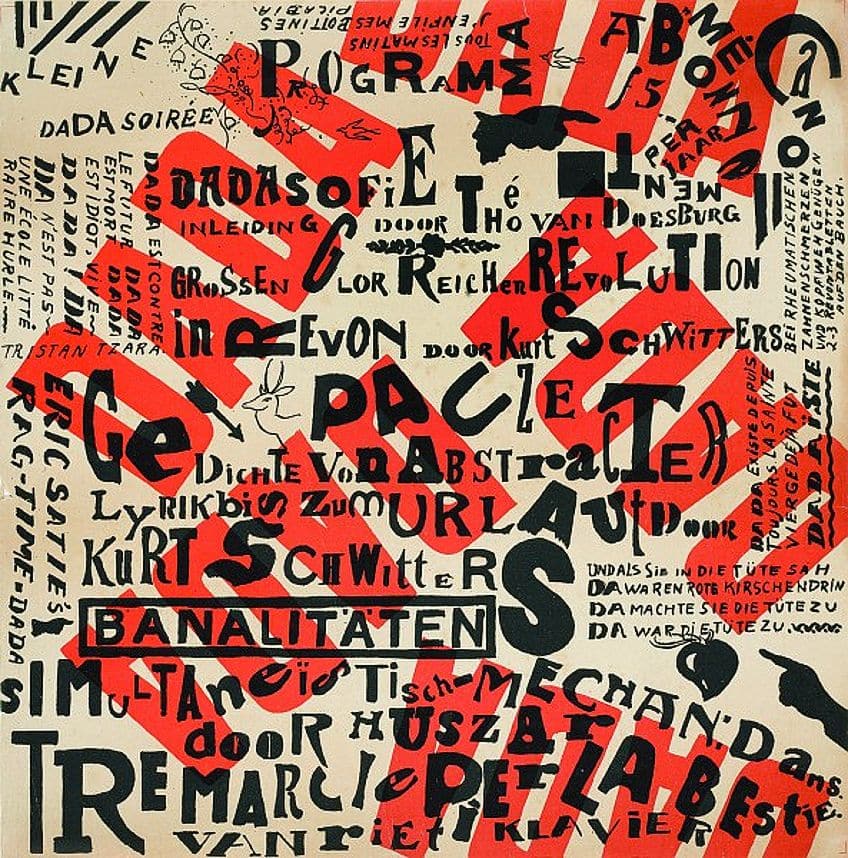

In 1918, following the end of the war, many Dada artists returned to their home countries. In April 1919, the Dada artists held a four-five Dada event in Zürich which, as was intended, ended in a riot. Tzara believed that this event would further undermine conventional art practices by involving the audiences in art production.

This practice would, in turn, encourage the growth of Dadaism. This event began as a Dada event, but eventually, over 1000 people attended. A closed-minded speech concerning the value of abstraction in art began the event and was meant to rile up the audience. Discordant music and several readings intending to rile up the crowd followed the speech, and it was successful. The active involvement of the audience in art production completely negated the norms of traditional art.

Shortly after the riot, Tzara journeyed to Paris. It was in Paris that Andre Breton and Tzara met. The theories drawn up by these two artists would later underlie the Surrealist movement. While the spread of Dadaism throughout Europe was not a self-conscious or intentional process, a few principal artists spread the ideas throughout several European cities.

Each artist would inform their group, and the cities would themselves influence the Dada aesthetics.

German Dadaism

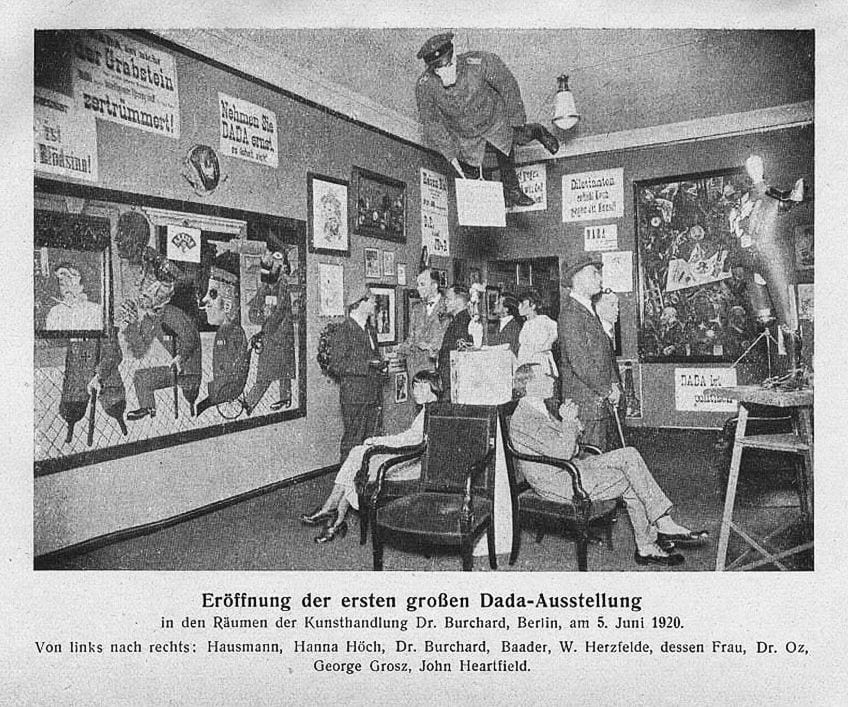

Dadaism reached Germany in 1917, following Huelsenbeck’s return. Once in Berlin, Huelsenbeck founded the Club Dada. The club was active between 1918 and 1923 and had many famous attendees, including Raoul Hausmann, Johannes Baader, Hannah Hoch, and George Grosz.

The art produced by Dada artists in Berlin was significantly more political than that of the founding members because of their proximity to the war zone. Satirical collages and paintings created using political cartoons, government officials, and imagery from the war publically rebelled against the Weimar Republic.

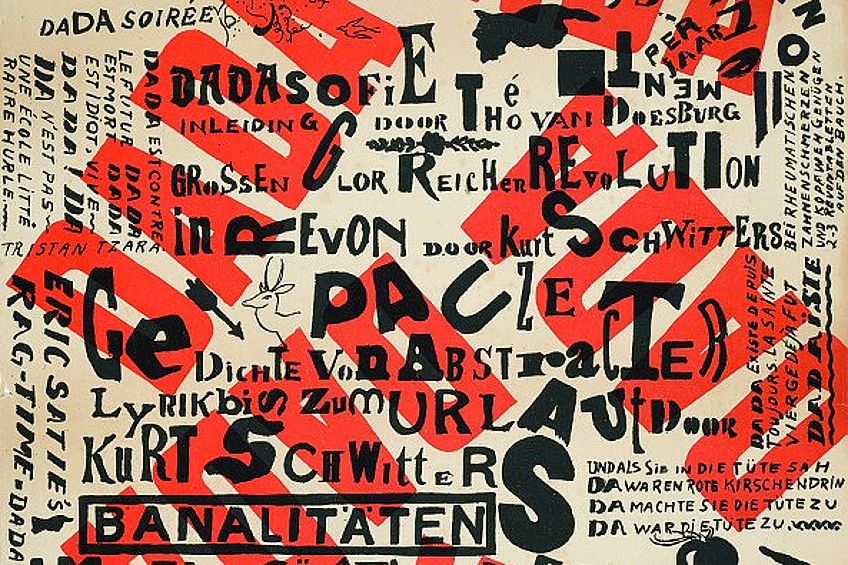

Huelsenbeck spoke publicly in Berlin about Dadaism for the first time in 1918. The speech was published in several magazines and journals, including Der Dada and Club Dada. During this period in Berlin, Dada artists began developing the first photomontage techniques.

1919 saw the founding of a separate Dada group by Kurt Schwitters in Hannover. Schwitters was not welcome in the Berlin group, possibly as a result of his links to Expressionism and the Der Sturm gallery. Berlin Dadaism stood firmly in opposition to both of these institutions because they focused on aesthetics and were too Romantic. Schwitters was the only member of this Dada group, and his artwork was much less political. Instead, Schwitters investigated the preoccupation of Modern art with color and shape.

Yet another Dada group sprung up in Cologne in 1918. Johannes Theodor Baargeld and Max Ernst were responsible for forming this group. These two artists were joined by Hans Arp a year later. Hans Arp, within this group, made several discoveries in his experiments with collage, and the anti-bourgeois artworks from this group centered around nonsensical art.

The police closed down one of this group’s 1920 exhibits, and when German Dada began to dwindle in 1922, Ernst moved to Paris, and the group dissolved. Dada artists began to take an interest in other art groups, including Constructivism and Surrealism.

Parisian Dadaism

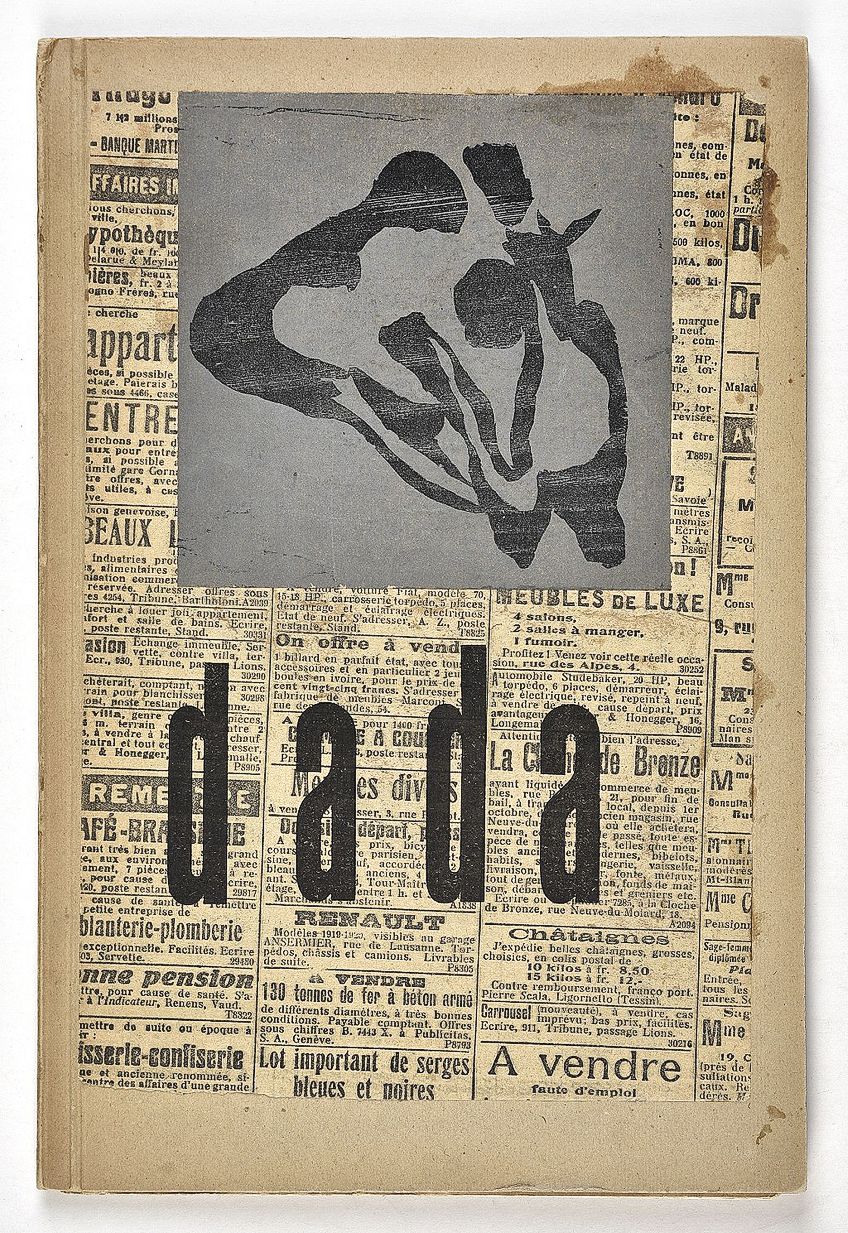

Paul Eluard, Louis Aragon, and Andre Breton heard of the birth of Dadaism art in Zürich and set about to create a group of their own. Tzara returned to Paris in 1919, and in the following year, Arp joined the group. In May of 1920, many of the originators of the movement attended the first Parisian Dada festival. Performances, exhibitions, and various presentations occurred, and the artists published several journals and manifestos, including Le Cannibale and Dada.

The Parisian Dada scene did not last very long, and by 1921, several members, including Breton and Picabia, had left. Picabia became so disillusioned with Dadaism art that he claimed that the movement had become the very thing it had fought against in a special issue of 391. Right before the final breath of Parisian Dada, the group held two final performances in 1923.

Following these performances, the group gave into internal fighting. Many former Dada artists ceded to Surrealism, with Marcel Duchamp playing a crucial role in bridging the gap between Dadaism from Zürich and the proto-Surrealism movement in Paris. Swiss Dadaism saw Duchamp’s refusal to define art and the humor in his readymades as falling into Dada.

New York Dadaism

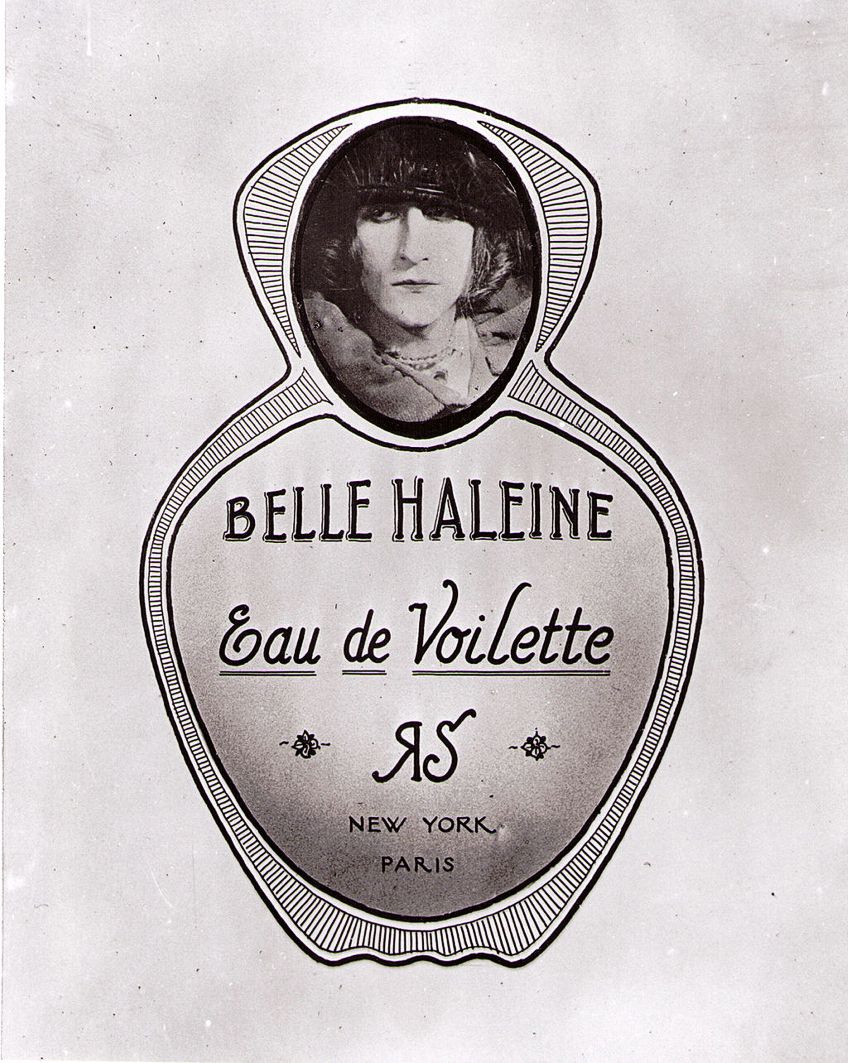

During the war, many artists and writers found refuge in New York, as well as Zürich. In June of 1915, both Picabia and Duchamp arrived in New York. Soon after their arrival, these two artists met Man Ray, and the three began making moves in the New York Dada scene. Duchamp was a critical driver of New York Dada because he brought anti-art notions with him.

Man Ray, who was later associated with the Kinetic art movement, brought a mechanized twist to New York Dada. Duchamp began one of his most famous pieces in New York. This was The Large Glass or Bride Stripped Bare by her Bachelors (1915). This piece was a milestone in the growing anti-art trend of dramatizing the erotic with mechanized shapes.

1916 saw other artists joining Man Ray, Duchamp, and Picabia. These artists and writers include Mina Loy, Beatrice Wood, and Henri-Pierre Roche.

Louis and Walter Arensberg’s studio and the 291 Alfred Stieglitz gallery were the central hubs for New York anti-art Dada activity. From these hubs came many publications, including New York Dada, Rongwrong, and The Blind Man.

Through these publications and their art installations, New York Dadaist artists presented a challenge to artistic conventions, with slightly less bitterness and more humor than their European counterparts. Duchamp’s first experiments with readymades began during this period in New York. It was in 1917 that he first presented Fountain. He presented this readymade creation to the Society of Independent Artists.

The Parisian, New York, and Zürich Dadaist groups were tied together thanks to the traveling of Picabia. Between 1917 and 1924, Picabia was responsible for publishing the 391 Dada magazine, a publication stemming from the 291 magazine by Stieglitz. Despite his basis in New York, 391 was released in Barcelona before Zürich, Paris, and New York. Wherever Piciabia resided, fellow artists and writers contributed to 391. Although the periodical was primarily literary, Picabia became the most prominent contributor.

Styles, Concepts, and Trends in the Dada Movement

Dadaism art presents us with difficulties in strictly defining its styles and trends. By definition, Dada aims to reject all possible labels and preconceived ideas. Many paradoxes and overlaps exist in Dada artworks. Dada works seek to make art more accessible and less institutional. In the same breath, Dada artists also aimed to leave enough mystery within each piece to allow for multiple interpretations.

Dada artists like Man Ray and Kurt Schwitters created abstracted works that highlight the metaphysical essence of the subject matter over the external aesthetic. Others Dada artists analyzed movement and form through representational depictions of scenes and people. Both of these methods fundamentally sought to deconstruct the norms of regular life in rebellious and challenging ways.

At the very basis of all Dada artwork is the intention of disrupting and rejecting all the trimmings of bourgeois society.

Regardless of Tzara’s insistence that Dada was not a statement, Dada artists became increasingly agitated by the political and social atmosphere and aimed to instill this same anger in their audiences. Several underlying concepts can be broadly applied to Dadaism, including assemblage, humor, irreverence, and chance.

Assemblages and Readymade Art

Duchamp was the first Dada artist to experiment with readymade artworks, but they soon became popular. Readymades are essentially an object that already exists and is presented as an artwork by a Dada artist. When an artist combined two readymades into a single work, it became an assemblage.

Bicycle Wheel by Duchamp is a perfect example of an assemblage. Other prominent assemblages and readymade artists include Man Ray, Ernst, and Hausmann. Readymades poked fun at art establishments and institutional ideas about creativity, a theme that would continue in many modernist art movements, including Pop Art.

The objects and their arrangement were typically guided by little more than chance. The introduction of chance or accident into the creative process was a conscious choice intended to challenge bourgeois ideas about artistic creativity. Although we have separated the Dadaist concepts of readymades and chance, it is a difficult separation. One of the most prominent features of readymades and assemblages is their apparent lack of sense. The bizarre nature of many of these artworks facilitated an easy merge with Surrealism.

Humor

Despite their serious and often angry reactionary approach to bourgeois institutions and politics, Dada artists infused their works with a great deal of humor. Dada humor predominantly took the form of irony, as can be seen in their love for readymades. Readymades highlight Dada irony because they communicate a message about everything’s lack of intrinsic value.

Dada artists also received significant flexibility and freedom in their artistic expressions as a result of irony. They were able to embrace and celebrate the absurdity of the world around them without being drawn into institutional seriousness. The ironic infusion in many Dada artworks also keeps the artists from getting carried away with enthusiastic dreams of utopian worlds. The foundations of Dada’s artwork lay in their use of humor to say a resounding “yes” to everything being art and art being everything and nothing.

Irreverence

Irreverent is one of the most accurate ways to describe Dada. Whether it is a lack of respect and concern for art establishments, or mass-production, the government, or the bourgeoise, Dadaism is steeped in irreverence. Each Dada group had a slightly different focus for their lack of respect. The New York group focused their irreverence on the art world, with most of their works being inherently anti-art. The Berlin group centered around anti-government ideologies, and the Hannover group was surprisingly conservative.

Accident and Chance

From Schwitters’ stunning compositions to Duchamp’s abstract assemblages, chance was a key concept in all Dada artwork. For Dada artists, embracing accident and random chance was a method for releasing creativity from rational control. Duchamp was welcoming of all accidents, like the crack in The Large Glass.

Schwitters was also a proponent of the use of chance in his works, gathering random pieces of debris from various locations. Alongside their lack of concern for preparatory work in the artistic process, and their love of slightly tarnished artworks, Dada artists’ fascination with chance underpins their lack of respect for institutional art methods.

Different Modes in the Dada Art movement

Dadaism was a very eclectic movement that explored a range of materials. Dada artists did not steer clear of using novel and unexpected materials in their works. Man Ray explored airbrush and photography techniques as a way of separating the artist’s hand from their work and introducing an element of chance, while Jean Arp experimented extensively with using random objects in collages.

Beyond typically artistic media, Dada artists also investigated performance art and literature. Hugo Ball, the artist responsible for the Dada Manifesto, experimented with liberating the written word from institutional conventions. Ball used syllables without sense to create Dadaism poetry. These nonsensical poems were often performed, bridging the gaps between different Dada media.

The Reception and Downfall of the Dada Art Movement

As they intended, Dada stirred up a considerable amount of controversy. Dada attracted fervent fans and avid critics thanks to its overhauling of traditional artistic practices, passionate experimentation with new modes of expression, and their rebellion against all social institutions. Some saw Dadaism as a revolutionary step along the path of Avante-Garde art, while others found works like the readymades to be little more than objects from the garbage heap.

Into the early 1920s, whether positively or not, Dadaism gripped audiences. Unfortunately, the movement was destined to fall apart. Many Dada artists began to drift towards Surrealism, diving deeper into the philosophy of expressing the subconscious.

Other Dada artists, who entered the movement as a result of the First World War, found the growing power of Adolf Hitler to be too much to bear. Adolf Hitler struck a heavy blow to the Modern art world, rooting out all that he thought to be “degenerate.” Many Dada artists saw the destruction and mockery of their works and chose to move to the United States.

Although many of the first members of Dadaism began to scatter across the globe, Dadaism’s ideals continued to smolder. You can see the threads of Dada throughout many Modern art movements in the 20th century, most significantly in Pop Art.

Pop Art cultural commentaries surrounding capitalist culture and growing consumerism echo the ideals that first drew Dada artists together. Despite the brevity of the movement’s life, Dada remains a noted and significant part of 20th-century modern art, and it has been celebrated in retrospective exhibits throughout the world.

Famous Dada Artworks

As the Dada artists would say, it is one thing to talk theoretically, but it is yet another to witness the soul of a movement in the pieces it produces. In this next section of the article, we discuss some of the most famous and influential pieces of Dada art.

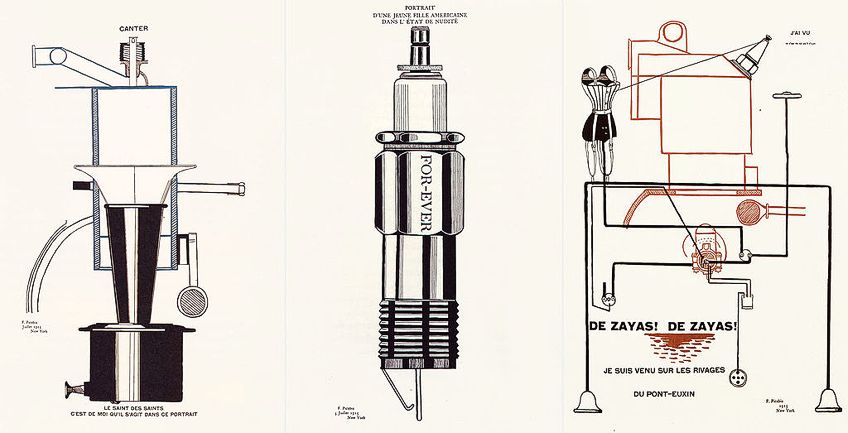

Francis Picabia: Ici, C’est Stieglitz (1915)

Picabia was a heavily influential member of Dada at its inception, so it is only right that we begin by looking at one of his first Dada works. For Picabia, pushing against conventions and re-defining himself was enjoyable. Throughout his 45 year career, Picabia re-defined himself and his style many times. Early in his career, Picabia worked alongside Alfred Stieglitz, and this may have inspired this portrait.

Stieglitz gave Picabia his first solo exhibition, but Picabia later criticized his former friend, as we can see in this portrait. The portrait features a bellows camera, intended to represent the gallerist, a brake lever, and gear shift, and a large “IDEAL” in Gothic font. The broken camera and neutral gear shift are thought to paint Stieglitz as being beyond his prime, a concept strengthened by the outdated gothic font.

This drawing is one of a series of mechanical imagery and portraiture. It is intriguing to note that while the imagery is mechanical, these drawings are not a celebration of progress or modernity. Instead, they provide a new subject matter, one that contrasts the institutionally accepted symbolism of the past.

Hugo Ball: Sound Poem Karawane (1916)

Hugo Ball is perhaps the most celebrated Dada artist, and he was responsible for writing the 1916 Dada Manifesto. The majority of Ball’s work was literary, and much took on the genre of poetry. In the same year that he penned the Manifesto, Ball performed this piece of Dadaism poetry. Here are the opening lines of Karawane:

“jolifanto bambla o falli bambla

großiga m’pfa habla horem”

Clearly, the poem does not make sense in our language, or probably any language, and it continues along the same lines. Although the poem appears to be little more than incoherent, nonsensical ramblings, Ball is offering a deep consideration of literature. The concept behind sound poetry was to remove everything from poetry but the vocalization of the human voice. By doing so, Ball demonstrates that you are still able to experience a rhythm and emotion through the poem, despite the lack of what we would call traditional meaning.

Some historians believe that the nonsensical nature of this sound poem was intended to represent the failings of rational discussion in the ability of European leaders to solve their problems. Ball was equating the failings of discussions that eventually led to the First World War to the biblical narrative, The Tower of Babel. During the performance, Ball wore a strange costume. This costume allowed him to distance himself even further from his surroundings and audience, making the poem appear even stranger.

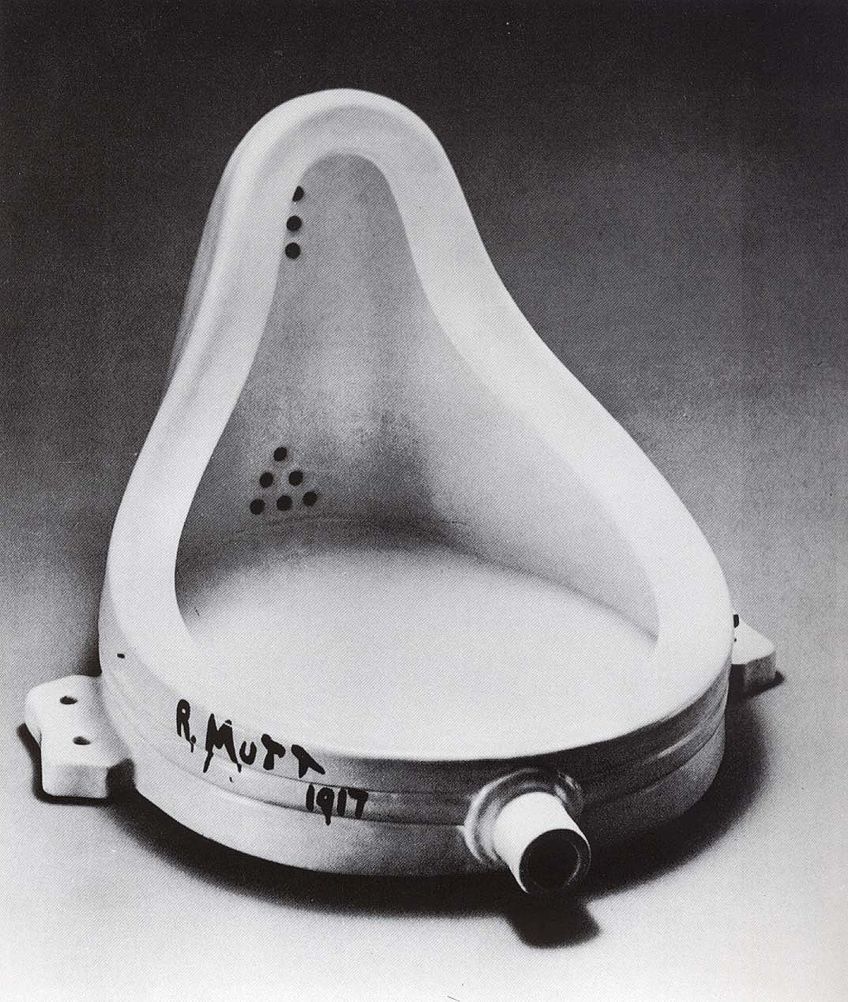

Marcel Duchamp: Fountain (1917)

Of all Duchamp’s readymade pieces, this is probably the most well-known. The choice to use a urinal and name it Fountain was a challenge even to Duchamp’s fellow artists. As with most of his readymades, he manipulated the urinal very little before display, simply turning it upside down and adding a fictitious signature.

A urinal is the farthest object away from what we socially understand as art. By removing it from its natural environment and placing it in a fine art context, Duchamp prompts us to question the fundamental definitions of art and the role of the artist in its creation.

The name Fountain is a humorous reference to the famous Baroque and Renaissance fountains and the purpose of a urinal. This piece is an icon of Dadaism, thanks to its ground-breaking deviation from tradition. Irreverence towards institutional production and design values fills every inch of this piece, and it has had an enormous influence on later 20th-century artists like Damien Hirst, Robert Rauschenberg, and Jeff Koons.

Hannah Höch: Cut with a Kitchen Knife Dada Through the Last Weimar Beer Belly Cultural Epoch of Germany (1919)

Known for her photomontage and collage compositions, Höch was a member of the Club Dada. Using clippings from magazines and newspapers, alongside her own craft and sewing designs for the Ullstein Press, Höch unashamedly criticized German culture. Her literal slicing up and reassembly of German cultural imagery into emotional, disjointed, and vivid depictions of modern life made her an integral member of German Dadaism.

The long-winded title of this piece is a reference to the sexism, corruption, and consumerist decadence of the culture in pre-war Germany. This collage is more political and much larger than many of her montages. Höch uses fragmentation in this anti-art work to shed light on the contradictions inherent in Weimer politics. The juxtaposed images of artists, radicals, intellectuals, establishment people, and entertainers highlight these polarities.

We can see many familiar faces in this fragmented photomontage, including Kathe Kollwitz, Lenin, Marx, and Pola Negri. The European map indicates which countries afford women the vote, suggesting or pushing for Germany to allow the newly enfranchised women to cut through the “beer belly” of male-dominated culture.

Höch breaks the boundaries between the spheres of public and domestic life and ties in commercial products, crafts, and modern art.

Marcel Duchamp: LHOOQ (1919)

What we may consider vandalism today, Dada artists saw as anti-art creations. This work by Duchamp is a perfect example of the irreverence of Dada towards traditional and classical art. On a postcard of the 1517 Mona Lisa painting, Duchamp drew a mustache and goatee. The label on the postcard, LHOOQ, letters that if pronounced by a French speaker, would sound like “she has a hot ass,” in French, of course.

As was his style and intention, Duchamp managed to offend almost everyone with this piece. At the same time, he provokes us to ask questions about the overall artistic cannon, the values of traditional art, and the role of the artist in creativity. The Mona Lisa had been stolen around 1911 and had only just been brought back to the Louvre when Duchamp created this piece.

Raoul Hausmann: The Spirit of our Time (1920)

This mechanical head assemblage is certainly Hausmann’s most famous work from the Dada period. Historians believe that the work represents the disillusionment that Hausmann felt towards the inability of the German government to make changes for the betterment of the nation. The sculpture consists of a wooden hat maker’s dummy with various objects attached to it, including a tape measure, a jewelry box, a ruler, brass camera knobs, a typewriter wheel, an old purse, and a leaking telescopic beaker.

The use of the wooden head echoes Hausmann’s attitude towards the typical person in a corrupt society who had only the capacity of what chance stuck to the outside of their head. The brain of these people, according to Haussmann, remains empty. Hausmann criticizes the inability for subtlety or critical thinking, representing these citizens as narrow-minded dummies with blind automation.

Max Ernst: Chinese Nightingale (1920)

Many of the pieces we have looked at so far have been quite political. In contrast, Max Ernst’s photomontages tend to be more poetic than the works of other German Dada artists. Rather than crafting a political message into his work, Ernst created images by randomly juxtaposing images. Ernst created Dada art by associating various elements that were completely alien in daily life to find the spark of poetry in their sudden and unexpected interactions.

In 1919 and 1920, Ernst created a variety of collages combining illustrations of human limbs, war machinery, and other objects. These collages emerged as bizarre, hybrid creatures which joined the fear of weaponry and death with lyrical titles and other innocuous elements. Many believe that these collages provided Ernst with catharsis following an injury caused by a recoiling gun in the war.

In this composition, Ernst uses the fan and arms of a Chinese dancer to represent the headdress and limbs of a strange creature whose body is a British bomb. Just above the side bracket of the bomb, Ernst has added an eye, creating an odd and unsettling bird-like creature. Using a sense of whimsy, Ernst is able to defuse the fear we associate with bombs, while still maintaining its other, more political associations.

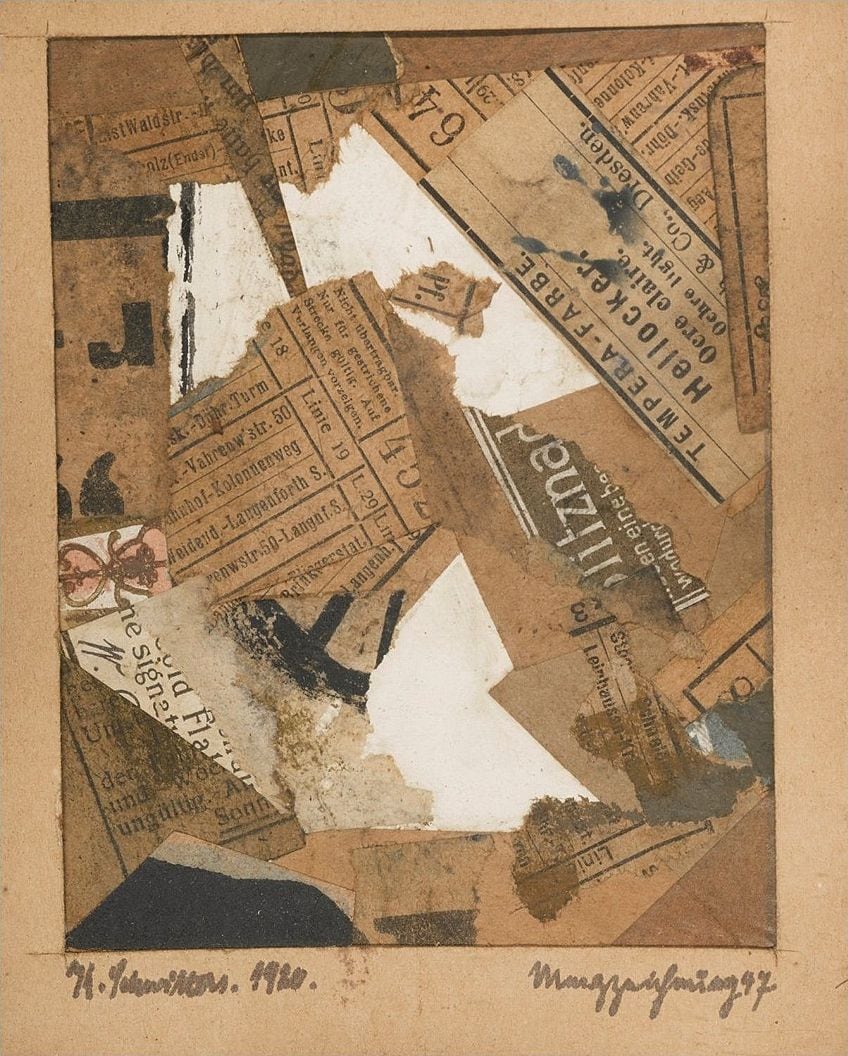

Kurt Schwitters: Merz picture 46A. The Skittle Picture (1921)

In this assemblage, Schwitters combines both three- and two-dimensional objects. The strange word “merz” at the beginning of this piece’s title is a nonsensical term that Schwitters used to describe his art method and many of his individual pieces. Apparently, Schwitters separated the term from “commerz.” Schwitters described his term as the fragments left by the turmoil of war that he used to compose new things.

His Merz pictures are often described as psychological collages. Schwitters would use small fragments of trash, including chess pieces, string, or ticket stubs, to create new and beautiful compositions. Much of Schwitters’ work is far less political, hostile, and dogmatic than other Dada works. EFor Schwitters, the focus was on using unique and non traditional materials.

Man Ray: Rayograph (1922)

Man Ray was part of the American branch of Dadaism. Although he was American, he spent many years working in France, where he developed his rayographs. These rayographs were experiments with photography, where Ray would place objects onto sensitized paper and expose them to light sources. The shadowy imprint left behind by these objects brings them away from their original context, purpose, and meaning.

Ray reflected the Dada values of nonsensical artwork in his rayographs which have a ghostly appearance and tend to be composed of unrelated and strange objects. The Dada fascination with chance is also reflected in many of these works. Ray’s works liberate photography from the grips of institutional tradition, while other Dada artists liberated sculpture, literature, and painting. In Ray’s hands, photography was no longer a direct mirror of reality but a tool to create unique and strange images.

In fact, the very existence of the rayograph is due to chance. Ray was waiting for an image to appear in his darkroom after he had forgotten to expose it. While waiting, he placed various objects on top of the photo paper. These rayographs were the purest form of Dada creativity, according to Tzara. Like-minded Dada artists loved Ray’s work, and while he was not responsible for inventing the photogram, his works are undoubtedly the most well-known.

Of all the Modernist and Avant-Garde art movements of the 20th century, there are none more bizarre and stimulating than the Dada movement. The artworks may seem confrontational and irreverent, and that is the point. Although the Dada movement lasted only a few years, it changed the course of 20th-century modern art and raised very necessary questions about society, consumerism, art, and politics.

Take a look at our Dada art webstory here!

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Dadaism – What Is the Meaning of the Meaninglessness of Dada Art?.” Art in Context. May 1, 2021. URL: https://artincontext.org/dadaism/

Meyer, I. (2021, 1 May). Dadaism – What Is the Meaning of the Meaninglessness of Dada Art?. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/dadaism/

Meyer, Isabella. “Dadaism – What Is the Meaning of the Meaninglessness of Dada Art?.” Art in Context, May 1, 2021. https://artincontext.org/dadaism/.