Etruscan Art – The History of Etruscan Painting

When was the Etruscan time period and what were the Etruscans known for? The Etruscan culture produced Etruscan sculptures, paintings, and other forms of Etruscan art between the 10th and 1st centuries BCE in central Italy. While there was a period where the Etruscan culture was heavily influenced by the Greeks, much of Etruscan statues, Etruscan pottery, and Etruscan painting retained their distinct traditional characteristics. Another aspect of their tradition was Etruscan funerary art. Let’s find out more about this fascinating era in art history.

An Exploration of Etruscan Art

Figurative sculpting in clay, wall painting, and metallurgy, particularly in bronze, were particularly prominent in this era. High-quality jewelry and etched jewels were also created. Cast bronze Etruscan sculpture was well-known and extensively exported, but only a few significant pieces have remained (bronze was too valuable, and subsequently reused). In comparison to bronze and terracotta, there was comparatively little Etruscan sculpture produced in stone, despite the Etruscan culture controlling good marble supplies, notably Carrara marble, which did not appear to be used until the Romans. The vast majority of the remaining artifacts came from tombs, which were usually stuffed with sarcophagi and grave items, as well as architectural terracotta sculpture remnants, primarily around temples.

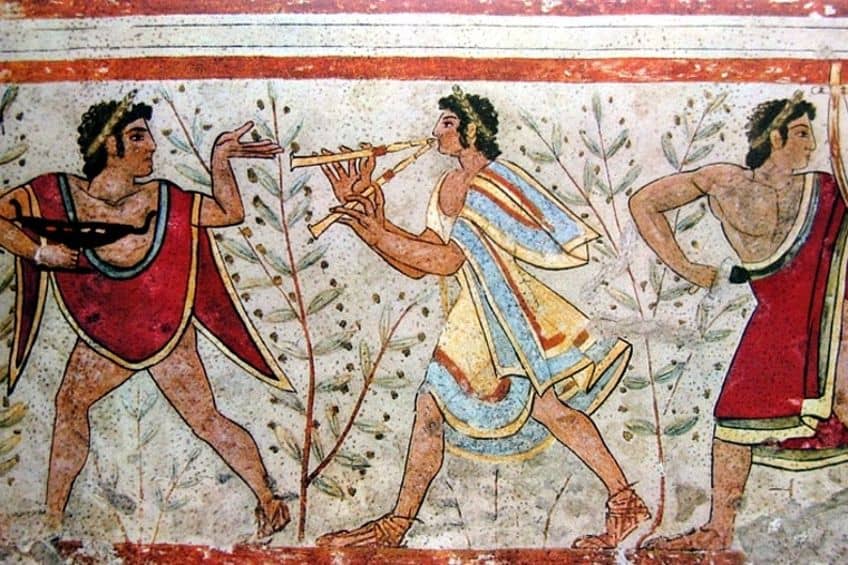

Every one of the fresco Etruscan paintings, which depict feasting scenes as well as a few mythological subjects, was produced in tombs. Bucchero ceramics in black were the earliest and most native Etruscan pottery types. There was also a legacy of complex Etruscan vase painting, which evolved from its Greek counterpart; the Etruscan culture was the principal export market for Greek vases. Etruscan temples were lavishly ornamented with colorfully painted ceramic antefixes and other fixtures, many of which survived even after the timber superstructure perished.

Etruscan art was deeply rooted in religion; the afterlife was a central theme in Etruscan art.

The History of Etruscan Art

The Villanovan civilization gave rise to the Etruscans. Several ancient cultures, such as Phoenicia, Greece, Assyria, Egypt, and the Middle East, shaped Etruscan art throughout the Orientalizing period due to their proximity and trade interaction with Etruria. The Romans would subsequently adopt the Etruscan civilization, but they would also be heavily affected by them and their artwork. Let’s look at the various Etruscan time periods.

Villanovan Period (900 – 700 BCE)

This is the earliest period of Etruscan art, which was named after the Villanovan civilization that flourished in central Italy at the time. Greek art, which was introduced through commerce and interaction with Greek colonies in southern Italy, had a profound influence on Villanovan art. The Villanovan period is distinguished by an emphasis on useful artifacts needed in daily living, such as Etruscan pottery and metallurgy. The pottery was usually painted with geometric patterns and forms, while metalwork was usually embellished with animal motifs.

In terms of early Etruscan statues and sculptures, the Villanovan period witnessed the development of miniature bronze figures, which were extensively used as votive objects.

These Etruscan statues, which often represented animals or human forms, were frequently buried in tombs or set in sanctuaries as sacrifices to the gods. During the Villanovan period, the Etruscan language developed, as did the establishment of urban settlements like Vulci and Tarquinia, which would subsequently become key hubs of Etruscan culture and art.

Orientalizing Period (700 – 575 BCE)

International commerce with existing Mediterranean civilizations interested in Etruria’s metals and other northern exports resulted in imports of foreign artwork, particularly that of Ancient Greece, and some Greek artists relocated. With palmettes and other patterns, the local decoration embraced a Greek and Near Eastern lexicon, and the foreign lion was a favored animal to portray. When the Etruscan ruling class became more prosperous, they started filling their vast tombs with burial treasures.

A local Bucchero pottery tradition, now employing the potter’s wheel, coexisted with the beginning of a Greek-influenced legacy of painted vases, which borrowed more from Corinth than it did Athens until 600 CE. The facial traits in the frescoes and sculptures, as well as the representation of reddish-brown males and light-skinned women, are influenced by archaic Greek art. As a result, these Etruscan paintings have very limited usefulness as a true portrayal of the Etruscan people. It wasn’t until the end of the fourth century BCE that physiognomic representations were discovered in Etruscan art, and Etruscan portraiture grew increasingly lifelike.

Archaic Period (575 – 480 BCE)

Despite conflicts when their different zones of expansion overlapped, prosperity continued to increase, and Greek influence expanded to the exclusion of other Mediterranean cultures. The Etruscan temple, with its ornate and vividly painted clay ornamentation, and other bigger buildings emerged during this Etruscan time period. Figurative art, which featured human beings and narrative situations, became more popular.

The Etruscans eagerly accepted Greek mythological stories.

Fresco Etruscan paintings began to appear in tombs (which the Greeks had stopped producing millennia earlier) and were maybe created for other structures. With the Persian invasion of Ionia in 546 CE, there was a large migration of Greek artist refugees, particularly in Southern Etruria. Other previous advancements continued, and the era produced a great deal of the greatest and most unique Etruscan artworks.

Classical Period (480 – 300 BCE)

The Etruscan culture had reached its political and economic apex during this Etruscan time period, and the volume of art created decreased slightly in the 5th century BCE, as prosperity shifted from the coastal towns to the interior, particularly the Po valley. Volumes were partly restored in the 4th century BCE, and earlier trends continued to grow without notable breakthroughs in the repertory, with the exception of the entrance of red-figure vase painting and more Etruscan sculpture, such as sarcophagi in stone instead of terracotta. Vulci bronzes were frequently exported across Etruria and beyond. The Romans were now conquering Etruscan towns one by one, with Veii falling victim in about 396 BCE.

Late Period (300 – 50 BCE)

The last Etruscan settlements were progressively assimilated into Roman culture during this time, and the degree to which art and architecture may be regarded as Roman or Etruscan is usually difficult to evaluate, particularly around the 1st century BCE. The production of unique Etruscan types of objects progressively disappeared, with the final painted vases emerging early in the era and big painted tombs ceasing in the 2nd century. Styles stayed within broad Greek tendencies, with greater complexity and classical realism sometimes accompanied by a lack of fire and personality. Bronze Etruscan statues, which were becoming larger in size, were occasionally reproductions of Greek models.

The massive Greek temple pedimental sculpture groups, albeit in clay, were imported.

Types of Etruscan Art

Etruscan art is recognizable by its distinctive style, which combines aspects of Egyptian, Greek, and Near Eastern art with the Etruscan people’s own artistic traditions. Etruscan art is filled with ornamental elements such as complex patterns, stylized animals, and legendary beings. Figures in twisted or distorted stances were popular among Etruscan sculptors. The Etruscans were famous for their terracotta sculpture, which was utilized both decoratively and religiously. Several Etruscan artworks, such as sarcophagi and Etruscan funerary artworks, reveal a fascination with the afterlife, with representations of the departed being welcomed into the underworld or taking part in burial ceremonies.

Etruscan Sculpture

The Etruscans were skilled sculptors, with many examples surviving in terracotta, both small-scale and massive, alabaster, and bronze. In comparison to the Greeks and Romans, however, there are very few produced in stone. Terracotta Etruscan sculptures from temples have almost all had to be rebuilt from a jumble of pieces, but examples from tombs, such as the unique type of sarcophagus tops with almost life-size reclining figures, have typically survived in great condition, although the paint on them has typically degraded.

Tiny bronze objects, typically with sculptural embellishment, were an important industry later on and were sold to the Romans and others.

The Apollo of Veii (c. 5th century) is an excellent example of the skill with which Etruscan artisans created these large-scale works of art. It was created, together with others, to ornament the temple on the Portanaccio’s roof. Although the architecture is evocative of the Greek Kroisos Kouros, the figures on the roof were an original Etruscan innovation. Apollo is portrayed in a dynamic position, with his right arm lifted as if carrying a bow and his left arm stretched forward. His hair is represented in complex, spiraling curls, and his head is inclined slightly to the side.

The deity wears a tunic and a quiver of arrows draped over his shoulder, and his attire and accessories are likewise beautifully detailed. It is noteworthy for its aesthetic combination of Etruscan and Greek elements. The dynamic attitude and expressive characteristics of the figure are representatives of Etruscan art, while the idealized body and meticulous representation of draperies reveal the influence of Greek art. The Etruscan statue is fashioned from terracotta, a medium that Etruscan artisans employed extensively for both aesthetic and practical purposes. It was initially beautifully painted, but most of the color faded over time.

Etruscan Paintings

The majority of the Etruscan paintings that have remained are wall frescoes from tombs, mostly in Tarquinia, and date from around 670 BCE to 200 BCE. With the exception of the Macedonian royal tombs at Vergina and the Tomb of the Diver in Paestum in southern Italy, the Greeks seldom decorated their graves throughout the equivalent time period. The whole legacy of Greek painting on panels and walls, probably the type of art that Greek peers regarded as their greatest, is almost fully lost, giving the Etruscan heritage great significance, even if it does not reach the brilliance and intricacy of the best Greek painters.

Literary sources indicate that temples, residences, and other structures had wall murals, but these, like their Greek counterparts, have all disappeared.

The Etruscan tombs, which contained the bones of entire families, were presumably locations for recurring family rites, and the topics of Etruscan paintings are likely more religious than they look. A few removable painted ceramic panels up to a meter tall have been discovered in graves, as well as fragments in city centers. The frescoes are formed by painting on new plaster, such that as the plaster dries, the artwork becomes part of the plaster and therefore an integrated part of the wall. Colors were produced by grinding up different colored minerals and mixing them into the paint. Animal hair was used to make fine brushes.

Chiaroscuro modeling was first utilized to depict depth and volume in the mid-4th century BCE. Occasionally ordinary events are depicted, but more commonly classic mythical subjects, mainly taken from Greek mythology, which the Etruscan culture appears to have thoroughly appropriated. Symposium scenes are prevalent, as are hunting and sporting scenes. The portrayal of human anatomy never reaches Grecian proportions. The notion of proportion does not occur in any surviving murals, and depictions of animals or men are usually out of proportion. Different forms of ornamentation fill a large portion of the surface between the figurative images.

Etruscan Pottery

Etruscan vase painting was created between the 7th and 4th century BCE and is an important component of Etruscan art. It was heavily motivated by Greek vase painting, and reflected the major stylistic movements of the time, particularly those of Athens, but lagged behind by many decades. The Etruscans employed similar processes and roughly similar forms. Both black and red-figure vase painting techniques were employed. In later eras, the topics were frequently derived from Greek mythology.

Apart from being makers in their own right, the Etruscan culture was the principal export market for Greek pottery outside of Greece, and some Greek artists may have relocated to Etruria, where elaborately adorned vases were a common feature of burial inventory.

It has been proposed that many of the most ornately painted vases were purchased specifically to be used in graves, as a cheaper and less likely to entice thieves alternative for the containers in bronze and silver that the aristocracy would have used in life. The burnished, unglazed bucchero terracotta goods, made black in an oxygen-deprived reduction kiln, are more completely indicative of Etruscan pottery art. Based on Villanovan pottery methods, this was an Etruscan advance. They may have finally constituted a typical “legacy” style preserved in use specifically for grave items, as they were typically adorned with white lines.

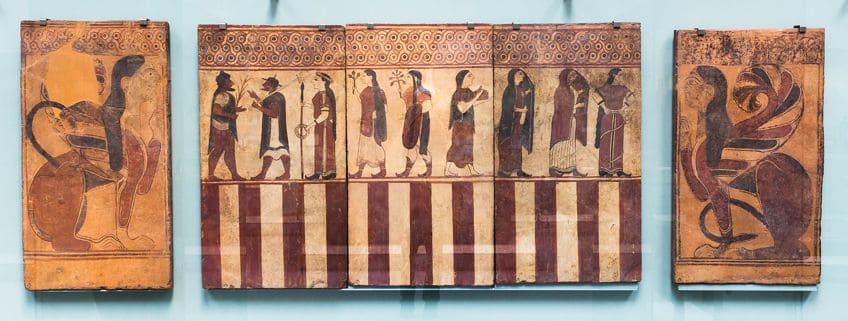

Etruscan Terracotta Panels

A few massive clay plaques, considerably bigger than normal in Greek art, have been discovered in tombs, some establishing a sequence that functions as a movable wall painting. The “Boccanera” tomb in Cerveteri’s Banditaccia necropolis featured five panels about a meter high arranged around the wall, which is now housed in the British Museum. Three of these appear to depict the Judgement of Paris, while the other two bordered the interior of the entryway, with sphinxes functioning as tomb guardians. These are from around 560 BCE. Pieces of comparable panels, apparently from temples, elite mansions, and other structures, have been discovered in city center locations, with the topics including portrayals of regular life.

Etruscan Metalwork

In the ancient world, Etruscan metalwork was highly valued for its meticulous workmanship, colorful themes, and technical mastery. Etruscan metalworkers typically used gold, bronze, and silver to create a broad range of items, including jewelry and miniature figurines as well as large-scale statues and architectural features. Etruscan mirrors were constructed of bronze and were frequently ornately decorated with mythical images, animals, and geometric patterns. Several of the mirrors were etched with Etruscan lettering and were carefully polished to produce a reflected surface.

Etruscan jewelry was typically made of gold and had sophisticated patterns that included animals, flowers, and other artistic elements.

The Etruscans excelled in granulation, which involves fusing small gold beads onto a metal surface to produce beautiful designs. From very early times, the Etruscans had a long heritage of working with bronze, and their little bronzes were frequently exported. In addition to casting bronze, the Etruscans were skillful at engraving cast pieces with intricate linear images, whose lines were stuffed with a white-colored material to emphasize them. In modern museum environments, however, with this white material lost and the surface inexorably degraded, they are regularly much less impressive and difficult to read than would initially have been the case.

Etruscan Funerary Art

The Etruscans were masters at depicting people. Both cremation and inhumation were utilized as burial methods throughout their history. Sarcophagi and urns were discovered in the same tomb, demonstrating the simultaneous usage of these objects across many generations. They began painting human heads on canopic urns in the seventh century CE, and they first buried their dead in ceramic sarcophagi in the late sixth century CE. These sarcophagi included a depiction of the deceased lounging on the lid, perhaps with a spouse. The habit of putting figures on the lid was created by the Etruscans, who subsequently encouraged the Romans to follow suit.

In Etruria, funeral urns with reclining figures on the lid, like small sarcophagi, attained enormous popularity. Funerary urns from the Hellenistic period were often fashioned in two sections. The top lid typically represented a banqueting man or woman, while the container component was either adorned in relief in the front alone or carved on its sides on more ornate stone pieces. Around this time, ceramic urns were mass-produced in Northern Etruria using clay. Generally, the relief pictures on the front of the urn depicted generic Greek-influenced subjects. Because the manufacturing of these urns did not need the use of expert artists, what we are left with is generally inferior, amateurish art produced in vast quantities.

Yet, the color selections on the urns provide date information, as colors utilized varied throughout time.

The Role of Religion in Etruscan Art

Religion was important in Etruscan art, with numerous pieces constructed for religious or ritual purposes. The Etruscans practiced a sophisticated polytheistic religion, and their art displays their great respect for the deities as well as their conviction in the necessity of ceremony and sacrifice. Many Etruscan artworks were made as deity gifts or as part of burial ceremonies, and they frequently depict religious subjects.

Tomb paintings, for instance, usually represent the departed conversing with gods or participating in religious activities, whilst bronze figures and Etruscan statues were routinely utilized in religious processions or as temple offerings. The Etruscan afterlife was unpleasant, in contrast to ancient Egypt’s optimistic outlook, where it was just a continuation of earthly life or ancient Greece’s confident relationships with the gods. The Roman fascination with Etruscan religion was focused on their methods of divination, propitiating, and understanding the will of the gods, instead of the gods themselves, which may have corrupted the knowledge that has been passed down to us.

That wraps up our investigation of Etruscan art and culture. The Etruscans’ art, which thrived in central Italy between the 10th and 1st centuries BCE, is known for its vibrancy and bright coloring. Wall murals were remarkably vibrant, typically depicting Etruscans having fun at feasts and banquets. Greek art, particularly work from Athens, was and still is highly regarded, but it is a mistake to believe that Etruscan art was only a bad imitation of it. The Etruscans may have lacked the finer methods of vase painting and stone sculpting that their Greek counterparts possessed, but other art forms like their goldwork, gem-cutting, and terracotta sculpting reveal that the Etruscans had higher technical expertise in these fields.

Frequently Asked Questions

How Is Etruscan Art Identified?

Etruria was never a single cohesive state, instead being a collection of separate city-states that developed both alliances and conflicts with one other over time. Despite their cultural similarities, these cities produced artworks that reflected their own interests and whims, making it hard to always accurately identify Etruscan artworks. Another challenge stems from the Etruscans’ failure to live in isolation from other Mediterranean cultures. Ideas and artifacts from Phoenicia, Greece, and the East arrived in Etruria via the ancient Mediterranean’s well-established trading networks.

What Was Etruscan Funerary Art Created For?

The Etruscans thought the deceased would require many of the same things they had in life. As a result, funerary art was developed not just to commemorate the departed, but also to present them with the tools and luxuries they would require in the hereafter. When it came to their tombs, what were the Etruscans known for? Etruscan tombs usually featured furniture, jewelry, and other personal goods that were thought to be important for the departed to resume their daily life in the hereafter.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Etruscan Art – The History of Etruscan Painting.” Art in Context. May 18, 2023. URL: https://artincontext.org/etruscan-art/

Meyer, I. (2023, 18 May). Etruscan Art – The History of Etruscan Painting. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/etruscan-art/

Meyer, Isabella. “Etruscan Art – The History of Etruscan Painting.” Art in Context, May 18, 2023. https://artincontext.org/etruscan-art/.