Renaissance Humanism – An Exploration of Humanism in the Renaissance

What does it mean to be human? This question lies at the heart of Renaissance Humanism, described as an intellectual movement during the 13th to 16th Centuries CE, which started in Italy and spread across Europe. It was a revival of the Classical era’s philosophies and ways of seeing the world. This article will explore the question, “What is Renaissance Humanism?” and look at some popular humanistic art.

Historical Background: What Is Renaissance Humanism?

Before we go all the way back to when Humanism started, let us first jump to the 19th Century. This is when the term “Humanism” originated. Two important scholars are worth noting, both of whom influenced the reception of the term and historically researched it as a “movement” during the Renaissance art era.

Georg Voigt, a German writer and historian, was one of these scholars. He started describing this movement and philosophical thought as “humanism”. He also wrote the theoretical text, Die Wiederbelebung des classischen Alterthums: Oder, das erste Jahrhundert des Humanismus (“Revival of Classical Antiquity or the First Century of Humanism”) in 1859, which explored the first century of the development of this term and idea.

The other scholar was Jacob Burckhardt, whose research on the Italian Renaissance had a wider scope than his counterpart Voigt. He explored the entire Italian culture and was considered one of the pioneers in the discipline of art history as well as cultural history.

It is also important to understand that during the Italian Renaissance, the word pertaining to the concept of “humanism” (as studied by Voigt) existed. These were in the form of humanista, which is Italian for “humanist” and the studia humanitatis, which is Italian for “humanistic studies”.

The concept, which was really a cultural movement, started during the Renaissance, and some scholars like Voigt believed it to have started with the poet and scholar Francesco Petrarca. Also known as Petrarch, he founded various lost manuscripts and documents written by the Roman philosopher, lawyer, poet, orator, writer, scholar, and statesman Marcus Tullius Cicero.

Cicero was an influential figure during the Roman period because of his intricate understanding and application of the Latin language. He extensively explored disciplines within the humanities in his writing, from philosophy, prose, rhetoric, and politics. Many described him as “eloquent” and on par with “eloquence”. He was also regarded as an authority on the Latin language.

It is no doubt that the depth of knowledge and wisdom that came from Cicero’s works and ideas sparked new insights in Petrarch when he found these Classical texts. In fact, it set the foundation for the Italian Renaissance and the return to the Classical era’s values and virtues.

It is also important to note that these ideas were discovered in many other Classical texts and not just from the ideas of Cicero alone.

“The Father of Humanism”

Petrarch was known as the “Father of Humanism” because of his contribution to this new way of perceiving man in relation to God. Although he was a Catholic and religious man, he also believed in man’s inherent abilities and greatness. He believed that God gave humans these abilities to live a virtuous life. This may have gone against what the church believed of man, who was said to be in need of God’s mercy.

Furthermore, Petrarch’s involvement in these new ideals also allowed other religious figures to involve themselves in it, which bridged a gap, so to say, between religion and the humanists’ ideals. For Petrarch, humanist ideals were about developing a better culture and society with morally guided human beings who able to go beyond illiteracy and the confines of the preceding Middle Ages.

This especially pertained to the tenets of Scholasticism, which was the dominant methodology for learning from around 1100 CE to 1600 CE.

During the 14th and 15th centuries, more people became educated in humanist ideals. The Latin school called studia humanitatis sought to educate in five major disciplines, namely grammar, history, poetry, moral philosophy, and rhetoric. Rhetoric was a major component of these studies and many people learned from other ancient Greek and Roman texts.

The Other “Forefathers” of Humanism

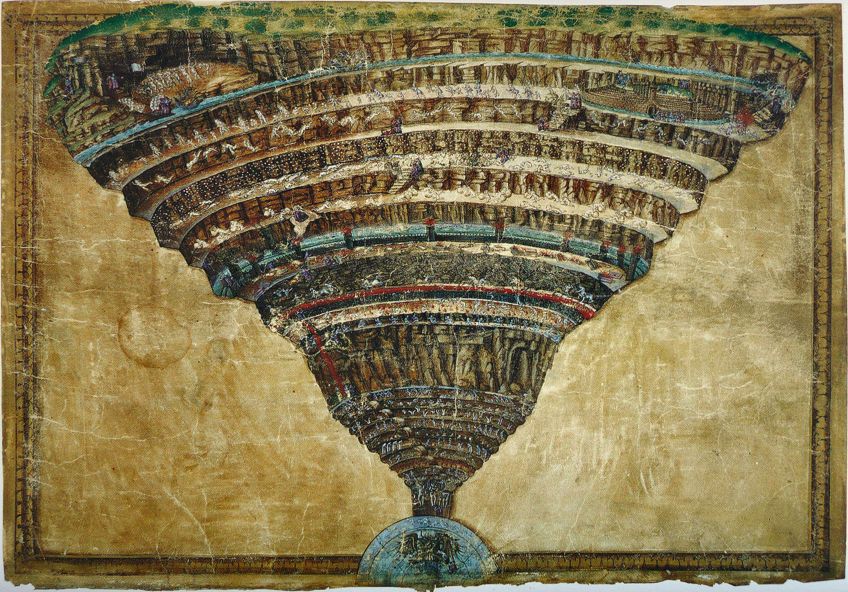

There were other scholars who contributed to the Renaissance humanist ideals and were seen as the “forefathers” of this movement along with Petrarch. These include the writers Dante Alighieri and Giovanni Boccaccio. However, Voigt also believed that Dante was not quite a matching counterpart to Petrarch in terms of Humanism because he came from the earlier Medieval period.

Dante wrote the Divine Comedy (1308 to 1320), a text about the afterlife reflective of Medieval beliefs. It is an influential text known for setting the foundations of Italian literature. It also contributed to the humanist movement – a slight shift away from solely religious sources – by including inspiration from Classical writers and philosophers like Virgil and Ovid.

Boccaccio was another famous literary catalyst, and friend of Petrarch, within the humanist movement. He wrote various short stories titled, The Decameron (1353), which many people related to because it pertained to relevant everyday experiences.

He was also influenced by ancient Classical texts and would become, along with Petrarch and Dante, one of the leading figures in Italian literature. Furthermore, these men wrote in their vernacular (everyday or native tongue), which made the understanding of the concepts easier for those people who did not understand Latin.

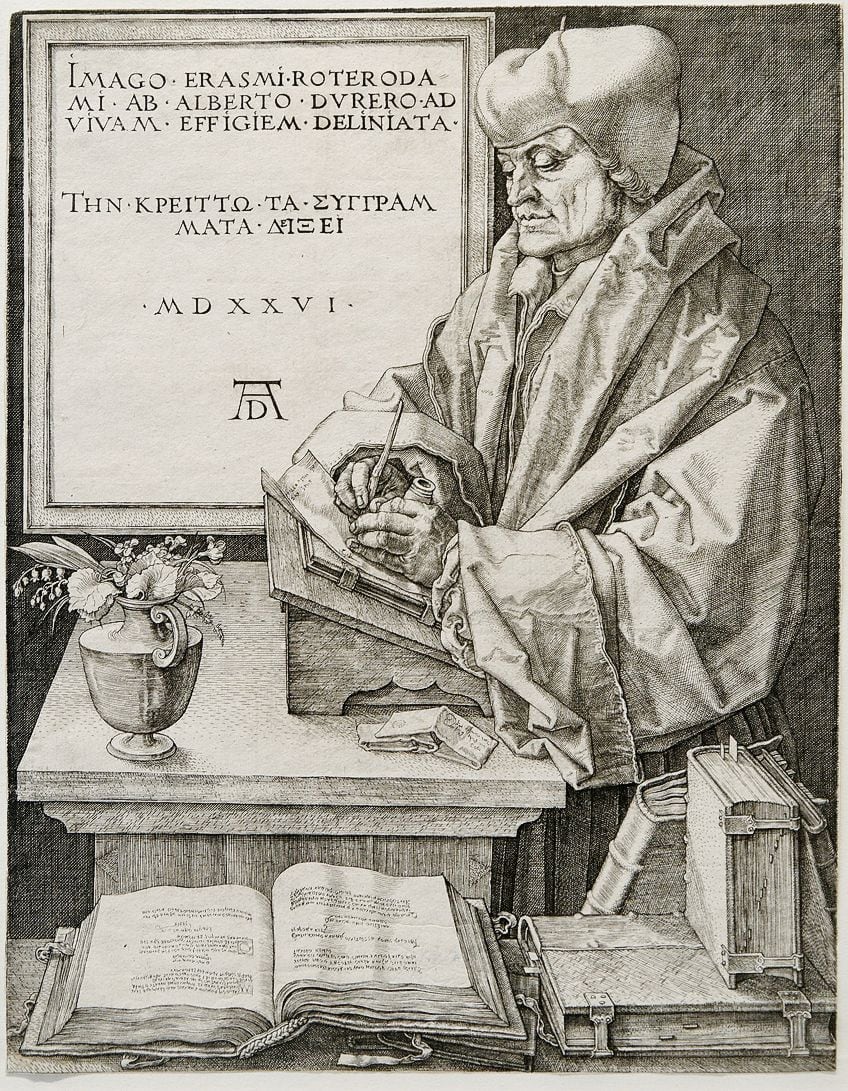

Another important figure in the humanist movement was the Dutchman Desiderius Erasmus. With the help of the newly innovated printing press, which allowed for the spread of ideas from Italy to other parts of Europe, Erasmus was able to disseminate more copies of Greek and Latin texts, especially of the New Testament.

Erasmus was a devout Christian, although his work utilized humanist ideals, and he strongly believed that education should be made available to everyone and not only a select few. Other agents of change within this movement were scientists and mathematicians like Nicolaus Copernicus, who proposed that the Sun was at the center of our universe and not the earth.

The Medici family, who were wealthy bankers and patrons of the arts, commissioned numerous artists like Botticelli and Michelangelo to create various paintings, sculptures, and pieces of architecture during the Early and High Renaissance periods.

The Medici family also contributed to further studies that involved humanist ideals. For example, it was Lorenzo de’ Medici who started the Medici Library, also known as the Laurentian Library. This housed the personal collections of books and manuscripts, as well as classical texts, collected by the Medici family over the years.

Platonic Revival

The Accademia Platonica (“Platonic Academy”) is believed to have been started and sponsored by Cosimo de’ Medici in the mid-1400s. It was like a modernized version of the original Platonic Academy in Athens, which was founded by the Greek philosopher Plato around 387 BC.

Marsilio Ficino, a Catholic priest, philosopher, and scholar, was assigned by Medici as the head of the new school. Ficino also translated all of Plato’s texts into Latin and was an important proponent of the Neoplatonic movement. There were numerous members that subscribed to the Neoplatonic thought – Giovanni Pico Della Mirandola is another example. He wrote the philosophical discourse titled, Oration on the Dignity of Man (1486), which became one of the most important texts within Renaissance Humanism thought.

Mirandola’s Oration was refuted by the Pope because it was viewed as unorthodox in its ideas, but nonetheless, it is often described as the “Manifesto of the Renaissance”. It explored controversial ideas around the many abilities of humans, and that man has higher capacities and more freedom than other animals.

It also explored the advantages of developing oneself as a human being through virtues like justice and reason. Mirandola also mentions magic and the Kabbalah. Overall, he emphasizes the uniqueness of being human and the aim to transcend this life. The act of transcending this life will come from virtuous living and choices made from higher faculties.

The return to the Classics was a significant addition to and development of Renaissance Humanism.

The Medici family’s love of art and the Classical era furthered the dissemination of the Classical ideals among society beyond Florence, especially in the form of translated texts (from Greek to Latin). Furthermore, it was a great discovery in and of itself because it revived Classical texts that were lost for hundreds of years after the closure of Plato’s School in Athens.

Humanism Art

The Humanism art definition can be described as art that spans painting, sculpture, and architecture during the Early and High Renaissance periods, underpinned by humanistic ideals. Many artists during this time drew inspiration and knowledge from texts by Classical writers and practitioners in disciplines like architecture and sculpture.

Artists during the Renaissance drew from fundamental humanistic principles, which shaped and informed their art. Many of these principles were based around the ideas of beauty, proportions, order, and rationality.

An important part of humanistic art is that art and science became interdependent disciplines; in other words, art was created with a scientific foundation and perspective, which informed its beauty and composition. Below, we look at some of the artistic techniques and concepts that developed, including the leading figures who explored them.

The “Vitruvian Triad” and the “Vitruvian Man”

The Roman architect, writer, and engineer, Marcus Vitruvius Pollio (also just known as Vitruvius) was active during the 1st Century BC. He was widely studied by Renaissance scholars and artists. His ideas contributed to how artists would design buildings and draw and paint the human form.

Vitruvius’ treatise, De architectura (“On Architecture”) (c. 27 BCE) was a compilation of 10 books that discussed Classical architecture and the Greek Orders, Roman architecture (including public and private buildings), building machinery, planning, decoration, and more.

What was significant about Vitruvius’ work was his holistic view on architecture and how it should impact people and the environment, as some sources state the “theoretical” and “practical” understanding of architecture was important to Vitruvius.

He introduced three characteristics or virtues, known as the “Vitruvian Triad”, to emphasize what a building or structure should look like, namely, firmitas (“stability” or “strength”), utilitas (“usefulness” or “utility”), and venustas (“beauty”).

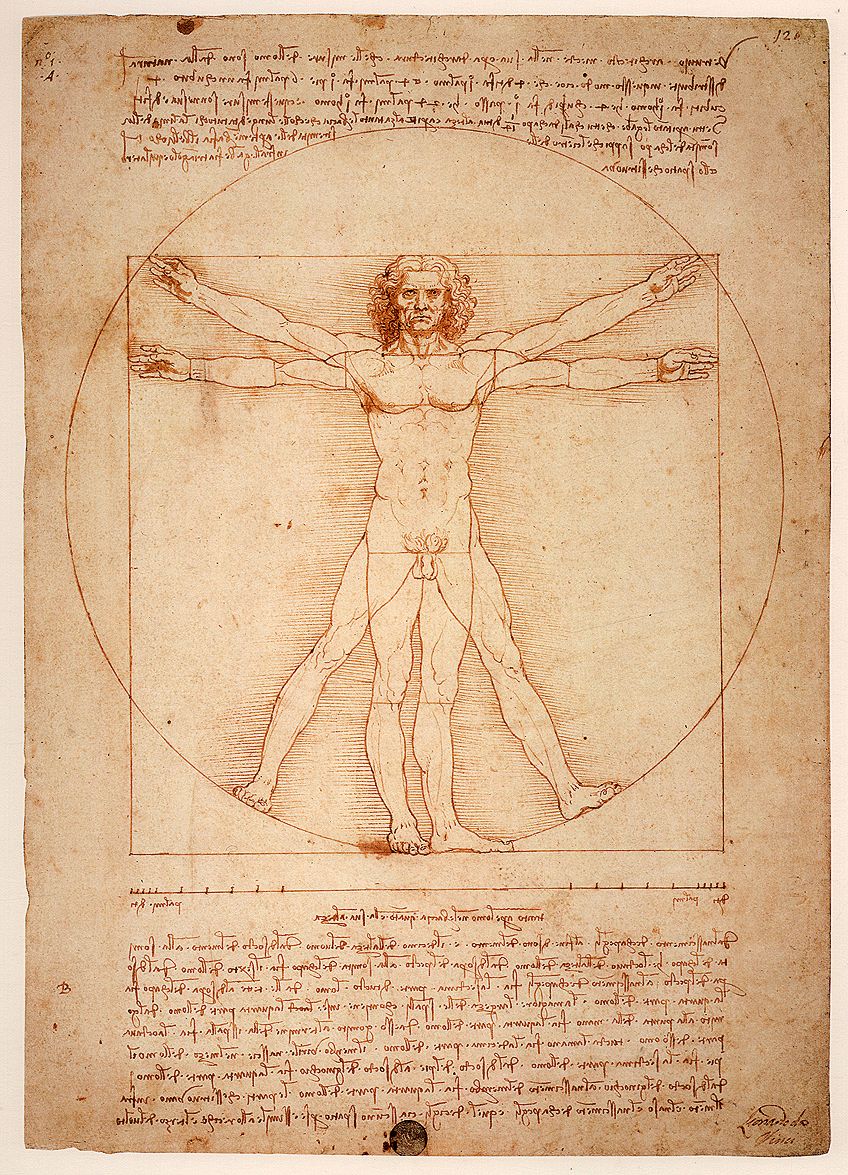

Vitruvius influenced several Renaissance artists, including the famous Leonardo da Vinci who painted the Vitruvian Man (c. 1485), which is also termed the Canon of Proportions. This painting depicts two poses (often described as superimposed) of a nude male figure standing with outstretched arms and legs that touch the edges of a circle and square around him.

This work is done according to the proportions stipulated by Vitruvius himself, although da Vinci also made corrections to the proportions. Below the image, we also notice written notes by da Vinci describing what Vitruvius was aiming for in his proportions of man. This illustration is the epitome of Renaissance Humanism, as it applies both the practical principles from mathematics and scientific observation and the balance and beauty from the perfect proportions.

Furthermore, it also emphasizes man’s central place in the universe; the square symbolizes the earth, and the circle symbolizes the sense of unity and oneness.

Linear Perspective

Linear perspective, or One-Point Perspective, was another new discovery made during the Early Renaissance. It was Filippo Brunelleschi, an Italian architect, sculptor, and engineer, who provided a mathematical study of how perspective worked. Although he was also a sculptor, he was more of an architect and pioneered the One-Point Perspective technique, which continued influencing many other Renaissance painters like Masaccio, Lorenzo Ghiberti, and Leon Battista Alberti (who was a close friend and follower of Brunelleschi).

Alberti was a significant contributor to modalities like painting, sculpture, and architecture. He provided theoretical frameworks and systems from his three treatises for artists that would place them above the more common designation of being just craftsmen – they would become studied and intellectual artisans of their crafts.

Alberti’s three treatises were Della pittura (1435) (“On Painting”), De re aedificatoria (1452) (“On Architecture”), and De statua (1464) (“On Sculpture”). These were some of the first theoretical publications on the different modalities of art, each one providing principles and techniques for artists.

“The Renaissance Man”

“The Renaissance Man” is an important concept that is a big part of what defines Renaissance Humanism, as it exemplifies someone who can achieve what they want and excel at many disciplines. This was true of many artists during the Renaissance, who were known as polymaths.

Alberti was among these and known as the first to introduce the concept of “Uomo Universale”, which is the Italian term for Universal Man, stating in his writings that “a man can do all things if he will”.

Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, and many others were also polymaths and excelled in painting, sculpture, architecture, engineering, drawing, inventing, poetry, literature, music, science, mathematics, botany, geology anatomy, and more. This placed the artist at a level of genius and the man as a central powerful force in the universe.

Famous Renaissance Humanism Artwork

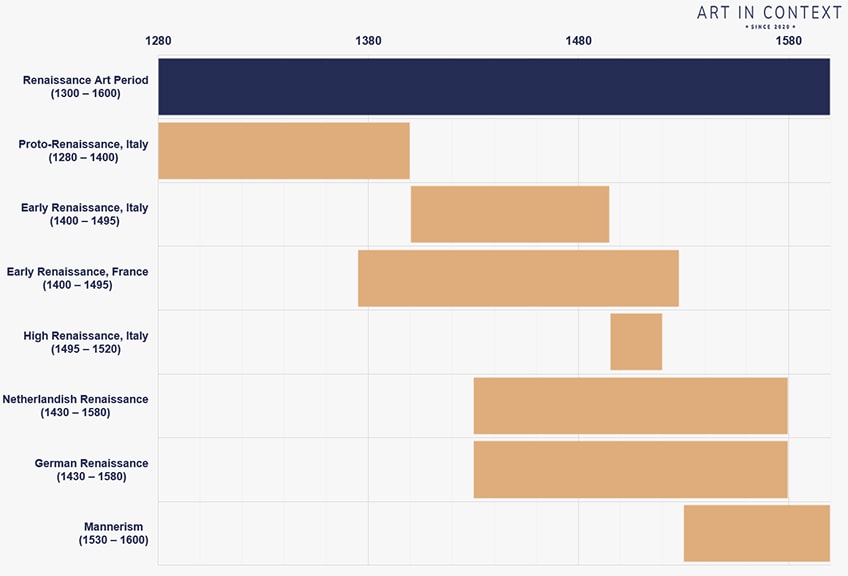

Below, we discuss some of the more famous Renaissance Humanism artworks spanned across the Renaissance time period. We will start from the Early Renaissance, during the 1400s, followed by the High Renaissance during the late 1400s to 1500s, and then mention some of the prominent artworks from the Northern Renaissance, which occurred during the 1500s.

Early Renaissance

There were numerous artists during the Early Renaissance, and we can start to see the emergence of Humanism ideals in how artists approached and redefined the subject matter they worked with. For example, religious or biblical figures were given more naturalistic qualities, which made the artwork easier to relate to. The idealized portrayal of divine figures from the prior Byzantine period was replaced with perfectly proportioned figures, often muscular in shape and with a radical human likeness.

Furthermore, artists started incorporating perspective in their compositions and created more depth and three-dimensionality by using mathematically based techniques and light sources.

Filippo Brunelleschi (1377 – 1446)

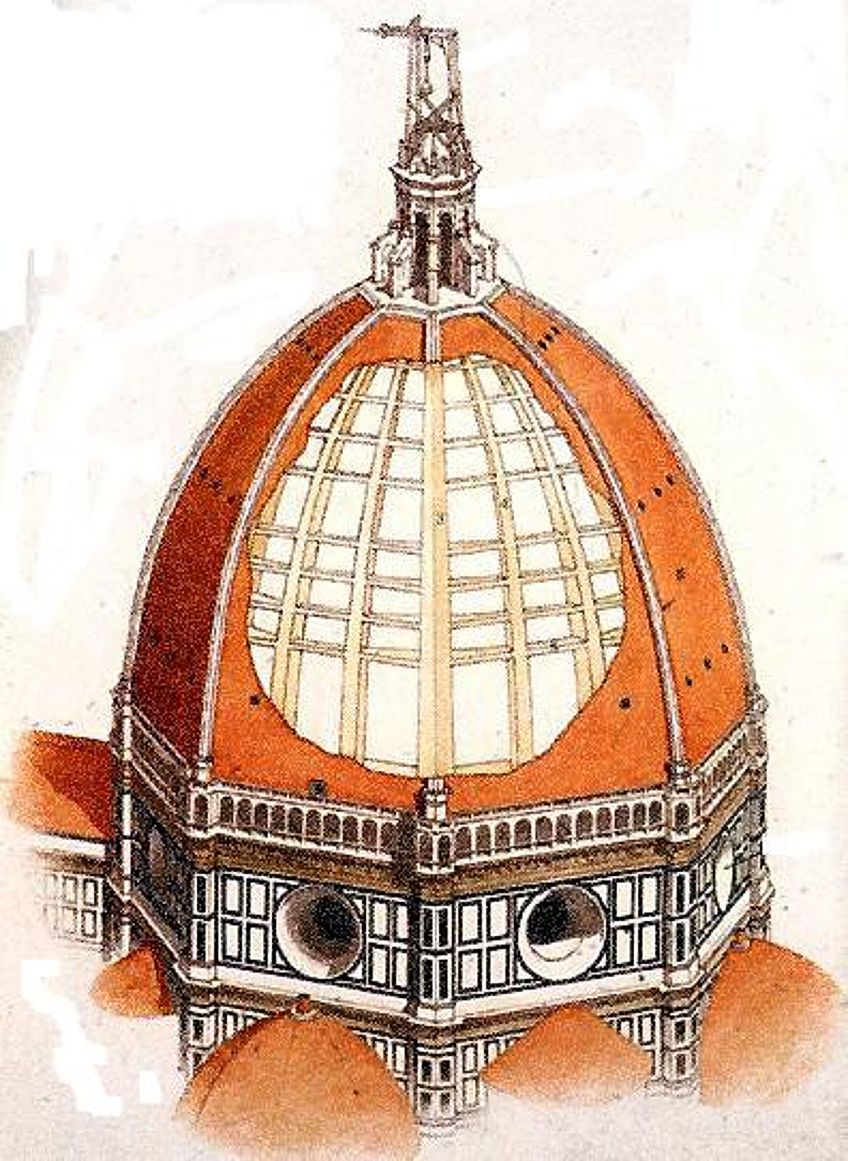

Filippo Brunelleschi designed the dome for the Cathedral di Santa Maria del Fiore (1296 to 1436) in Florence. This cathedral was one of the most significant buildings during the Early Renaissance and is an exemplary structure that gives life to humanistic ideals. It embodies mathematical accuracy in its proportions while simultaneously standing at 372 feet tall in its red brick beauty.

Brunelleschi built the dome in an innovative way, building a dome within a dome in order to create enough support for the building to prevent the dome from falling in on itself. He also designed new mechanics to assist during the building process.

This building is a testament to Brunelleschi’s skills in combining not only his knowledge of Classical architecture but also mathematical principles in order to create something similarly beautiful.

Other buildings by Brunelleschi include his public building, Ospedale degli Innocenti (meaning “Hospital of the Innocents”), which he started in 1419. The design was influenced by Roman architecture, late Gothic, and Italian Romanesque styles. This building is another example of the order and harmony portrayed in the structure and layout of columns, capitals, and archways.

Donatello (1386 – 1466)

Donatello was a sculptor during this period, famous for his bronze statue titled David (1440 to 1443). It is described as an “iconic” humanistic art piece because of the way Donatello portrayed the biblical figure of David.

Firstly, this is a nude, free-standing statue of a male figure – the last time we saw nude statues was during the Classical era. The semi-erotic and youthful biblical figure stands with the head of Goliath between his legs, a sword in his right hand, and his left hand resting on his left hip.

What makes the figure more erotic in nature is his effeminate body shape, long hair, and softer appearance as opposed to what we would expect from someone who had just killed a Goliath. Additionally, he has a laurel wreath in his hat and well-designed boots. His stance is in the classical contrapposto pose, which is a characteristic of many figures during the Renaissance era. It also gives a new sense of movement and relaxation to the figures.

This was another revival of techniques from the Classical era.

Paolo Uccello (1397 – 1475)

Paolo Uccello brought perspective, vanishing points, and light to life in his painting The Battle of San Romano (1435 to 1440) – another testament of humanistic art. This painting is part of three panels, depicting a battle scene between the Florentines and Sienese.

Examples of how Uccello portrayed perspective include the red and white lances on either side of the composition, almost leading our eyes to the vanishing point in the distance. This is further led by the lines from foliage in the distant fields. The foreground is full of action with striking reds, blues, and whites crowding the space.

Other examples of Uccello’s artwork include St George and the Dragon (c. 1455 to 1460) and the Hunt in the Forest (1468 to 1470). The latter is another example of Uccello’s skillful utilization of linear perspective. We notice various figures, some on horses and on foot, with dogs running in the foreground moving into the receding forest ahead. This creates a sense of movement and three-dimensionality.

It is also important to note that Uccello painted in the Late Gothic style, and did not paint in the typical style we see in other Humanistic art, where figures are characteristically classical and portrayed with naturalism. What made his artwork stand out within the Humanism field was his precise preoccupation with linear perspective and utilization of color to create a heightened effect on the subject matter.

Masaccio (1401 – 1428)

The artworks by Masaccio, a Florentine painter, give a good example of how artists started incorporating perspective and naturalism in their subject matter and compositions. It is because of this that Masaccio is known as the “Father of the Renaissance”.

We can clearly notice the move away from the Gothic style that preceded this period of “rebirth”.

Masaccio’s Payment of the Tribute Money (1425 to 1427) was done for the Brancacci Chapel of the Santa Maria del Carmine and is part of a series of other paintings with religious themes. We notice that the artist is focusing on three narratives here (referred to as a continuous narrative) about the life of St. Peter.

The central figures are Christ with his disciples and the tax collector asking for payment. We notice Jesus pointing to Peter to collect the money. To the left of the painting, Peter is taking the money from a fish’s mouth, and to the right of the painting, we see him paying the tax collector.

There are various characteristics in this painting that suggest it is an example of humanist thought or influence. Namely, the figures are portrayed in a classical manner, evident by their draping robes, appearing as if they are statues from Antiquity. However, there is also a naturalism in their expressions and stances, which highlights their humanness.

Furthermore, Masaccio incorporated linear perspective and proportion in the landscape in the distance and in the architectural designs of the buildings in the foreground.

There is also a light source evident by how the artist depicted the cast shadows by the feet. This was another revolutionary characteristic of Masaccio’s painting because it indicates a sense of weather and gives the whole composition a three-dimensionality never seen before.

Alessandro Botticelli (1445 – 1510)

Otherwise known as Botticelli, we notice the move away from strict religious figures in his famous paintings La Primavera (c. 1482 to 1483) and The Birth of Venus (c. 1484 to 1486). Both paintings depict classical mythological scenes of the goddess Venus surrounded by numerous other gods and goddesses.

In La Primavera, we see the central figure of Venus, and to her left is the goddess of Spring, Primavera, and Chloris, a nymph, pursued by the god of wind, Zephyrus. To Venus’ right are the god Mercury and three dancing graces. Above Venus’ head is the smaller figure of Cupid shooting an arrow towards the three graces.

This painting is also believed to indicate the influences of Neoplatonic thought. Some sources suggest that the painting solely focuses on aesthetics and love (tied to the beliefs posited by Plato), evident by the composition and how the subject matter is arranged in a beautiful manner, from the figures all the way to the flowers strewn on the ground.

Other sources suggest the painting depicts narratives from Ovid, who was a Roman poet alive during the time of Emperor Augustus. Ovid was also regarded as one of the best Roman poets, along with Virgil and Horace, in the field of Latin literature. Furthermore, Botticelli was also exposed to the humanistic movement of the time and a follower of Dante’s work, as well as the philosopher Marsilio Ficino, who translated Plato’s texts.

This provides more context for Botticelli’s rich humanistic art.

High Renaissance

Starting around 1490 to 1527, the High Renaissance was a period of refinement of many of the techniques from the Early Renaissance. Some artists also pioneered new techniques, for example, da Vinci’s sfumato, and used new media like oils. This period in the Renaissance was almost like the epitome of artistic virtue and genius.

There were many artists who created masterpieces of art, but three have taken the spotlight, so to say. This was Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Raphael. Another artist includes Donato Bramante, who was a leading architect of the time. The High Renaissance saw artists taking the stage as embodiments of the “Universal Man” or “Renaissance Man”, the core tenet of Humanism. Artists were considered geniuses; many were polymaths and excelled at a plethora of disciplines beyond art, indeed, personifying the Humanism culture.

Below, we look at some of the famous humanistic art from this period.

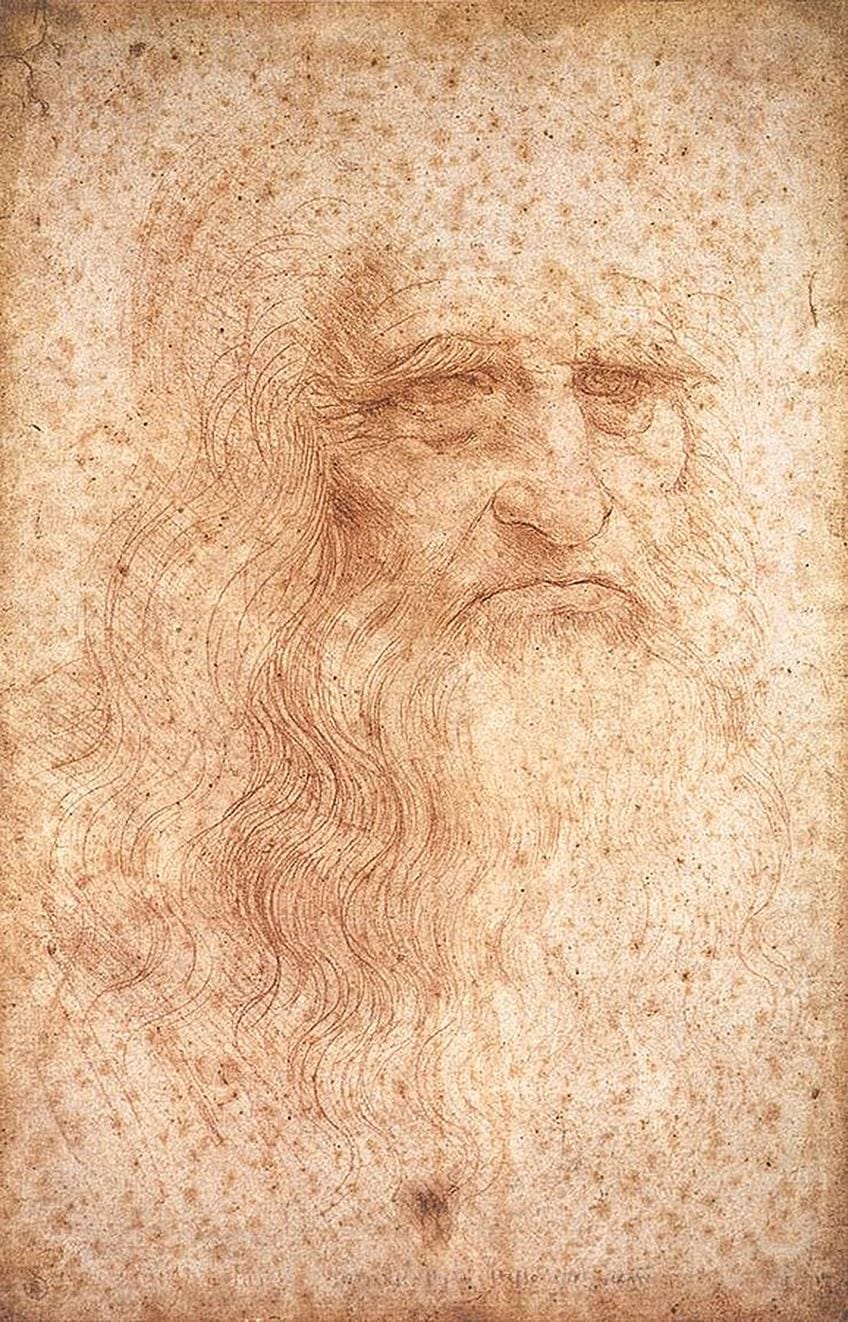

Leonardo da Vinci (1452 – 1519)

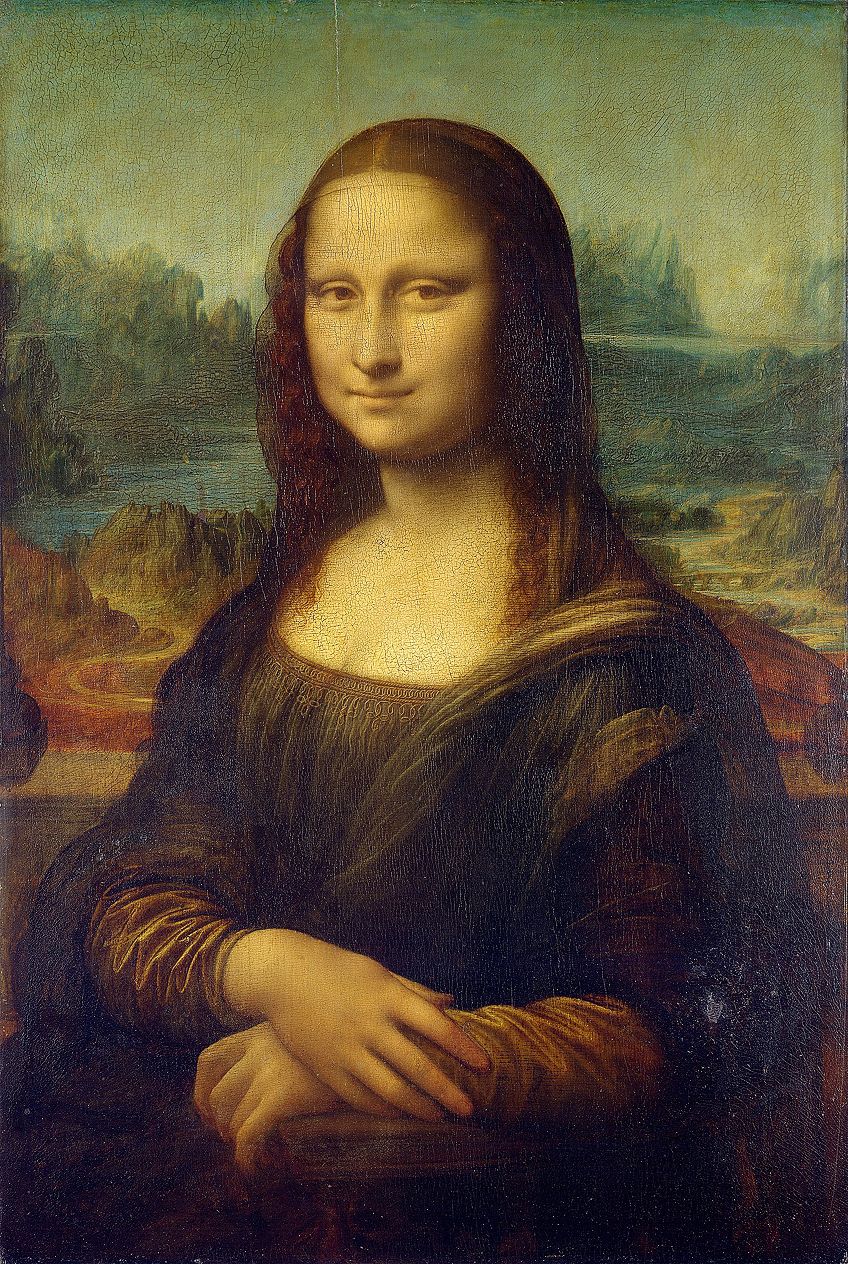

Da Vinci produced many masterpieces during his time, some including the famous Mona Lisa (1503 to 1506), Salvatore Mundi (c. 1500), The Last Supper (1498), and Virgin of the Rocks (1483 to 1486). In da Vinci’s paintings, there is a heightened sense of naturalism, noticed in each figure’s stance and facial features. There is also a mysterious quality in how the artist portrayed certain facial expressions, which we can see in the Mona Lisa’s hint of a smile as she gazes at us from her seat.

In Virgin of the Rocks, da Vinci portrays religious subject matter. However, it is with an element of mystery, again, due to the unknown rocky, cave-like background behind the Virgin Mary, who is sitting with the infant figures of Christ and John the Baptist, and the archangel Gabriel.

In this painting, we notice da Vinci’s skilled craftsmanship (or genius) at painting. He creates three-dimensionality with numerous techniques like sfumato, which blends the lighter and darker colors to give the composition an intensity and emotiveness.

Although we see the portrayal of religious subject matter throughout da Vinci’s works, he does not create a sense of idealism in the figures. He almost brings the figure down to earth, making them appear human-like, which is something everyone can relate to.

Described as “humanizing the secular”, da Vinci’s work is a clear example of humanistic art.

Michelangelo (1475 – 1564)

Michelangelo’s David (1501 to 1504) is another masterpiece indicative of Humanism ideals. It is the figure of David with a slingshot over his left shoulder. This is a marble statue of the biblical figure, although it is embellished with the classical contrapposto stance, as well as the fact that it is the first nude marble sculpture since Antiquity.

Michelangelo is almost transporting us back to the Classical era, where marble statues of muscular nude males were the epitome of the human figure. In fact, this statue is estimated to stand at over 17 feet tall and is a perfect depiction of the ideal male form, in turn, becoming the perfect depiction of beauty.

Raphael (1483 – 1520)

In Raphael’s School of Athens (1509 to 1511) we are reminded again of Classical revival. The whole composition is Classical in nature, depicting various philosophers talking and contemplating. The surroundings are also suggestive of classical architectural structures, for example, the columns and arches, including the design being of a Greek cross.

Plato and Aristotle are the two central figures. Other famous Greek philosophers include Pythagoras, Ptolemy, and Euclid, among others. There appears to be a fluid discourse between all the figures, also suggesting the amalgamation of the various disciplines of the humanities and the avid desire to learn about all types of intellect.

There are two statues, the Greek god Apollo to the left and the goddess Athena to the right. Each corresponds to the two primary philosophers in the center (Plato and Aristotle). The composition is also dynamic, and we almost feel a part of the bustling crowd – the arch bordering the scene in the foreground suggests almost as if it is a stage we can walk onto any moment.

Northern Renaissance

Artists in the Northern parts of Europe were not as interested in the Classical as the Italian artists were. Nonetheless, Humanism still prevailed throughout these parts of Europe. Desiderius Erasmus is described as the “Prince of the Humanists”. He was a Catholic priest and translator of various texts including the New Testament (1516).

A distinguishing characteristic between the Northern Humanists and Italian Humanists was a focus on creating a personal relationship with God versus being told by the Church how to relate to God.

There was a turn towards more ethical ways of living, as well as a focus on more everyday lifestyles of the ordinary human being as an individual. Nature was also studied and portrayed in artwork, which gave rise to new genres of painting like still lifes, landscapes, and portraiture.

Albrecht Dürer (1471 – 1528)

In Albrecht Dürer’s painting titled, Self-Portrait with Fur-Trimmed Robe (1500), we become aware of the Humanist perspective because the artist is placing himself, as an individual, as the primary subject matter of the painting (compared to how artists were often secondary in paintings, depicted as figures in the background, with minimal focus on them).

He is gazing right at us with a serious and stern facial expression, and he is wearing a dark brown fur-trimmed coat. His right hand is raised up touching his coat; some sources suggest his fingers are reminiscent of a gesture of blessing.

The figure appears almost Christ-like, emphasized by his long hair falling neatly down both shoulders. The background is also dark with a lighter side on the right. The artist utilizes the technique called chiaroscuro to depict the transition from light to dark.

Albrecht Dürer was an important Northern Renaissance artist because he was exposed to the Humanist movement in Italy and was influenced by other artists like da Vinci. He was also a part of Humanist circles in Nuremberg. He explored mathematical concepts like perspective and proportion and wrote several treatises, namely, Four Books on Measurement (1525) and Four Books on Human Proportion (1528).

Beyond the Human

While Humanism was a cultural development, or zeitgeist, so to say, of the Renaissance era, bringing about many socio-political changes for the Western civilization, it was also replaced by other movements that did not feel the need to depict perfect proportions or symmetry.

The Mannerist art movement developed shortly after the Renaissance came to an end. Artists started creating subject matter and figures that were not in proportion with offset perspectives. There was a clear move away from the classical values of order and harmony from before. The art movement after Mannerism was called the Baroque period, which revisited certain aspects from Renaissance Humanism like naturalism, perspective, as well as mythological subject matter.

The Renaissance Humanism movement certainly set the stage for new ways of seeing the individual, the world, and the universe. It questioned many beliefs and perceptions of man’s place in the greater scheme of things. It was a cultural blossoming of ideas in almost every discipline available, from literature, music, visual arts, and architecture to science, technology, engineering, astronomy, and so much more.

Take a look at our Humanism Renaissance webstory here!

Frequently Asked Questions

What Was Renaissance Humanism?

Humanism in the Renaissance was a cultural and intellectual movement during the 13th to 16th Centuries CE. It started in Italy and its ideas spread across Europe. It was considered a revival of the Classical era’s philosophies after the discovery of lost books by Greek and Roman philosophers like Plato.

What Is the Humanism Art Definition?

The Humanism art definition can be described as art during the Early and High Renaissance periods influenced and informed by the prevalent humanistic ideals of the time. Many artists during this time drew inspiration and knowledge from texts by Classical writers and philosophers. The ideals of beauty, order, and symmetry underpinned many of the Humanistic artworks.

What Were the Characteristics of Renaissance Humanism?

Humanism in the Renaissance is characterized by the avid studying of ancient literature from the Classical era, studying languages like Latin, moving away from Scholasticism, providing and believing in education to develop a better human being, the belief in the power and autonomy of the individual, virtues, ethics, and critical thinking, as well as creative exploration in the arts.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Renaissance Humanism – An Exploration of Humanism in the Renaissance.” Art in Context. June 30, 2021. URL: https://artincontext.org/renaissance-humanism/

Meyer, I. (2021, 30 June). Renaissance Humanism – An Exploration of Humanism in the Renaissance. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/renaissance-humanism/

Meyer, Isabella. “Renaissance Humanism – An Exploration of Humanism in the Renaissance.” Art in Context, June 30, 2021. https://artincontext.org/renaissance-humanism/.