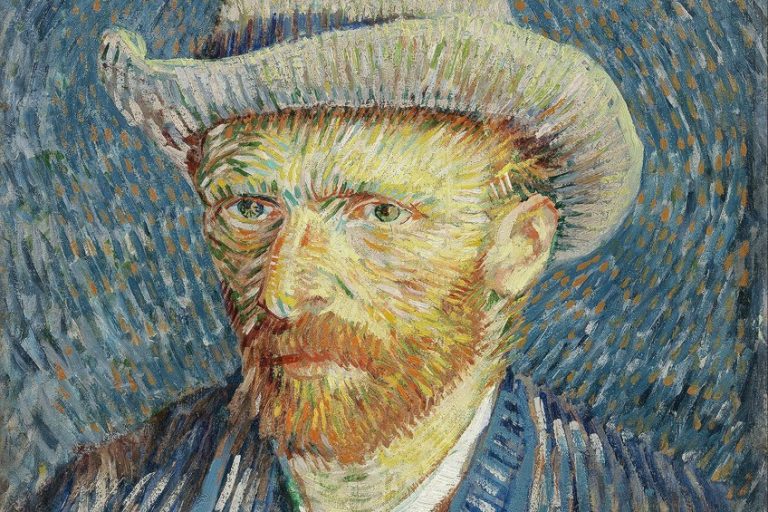

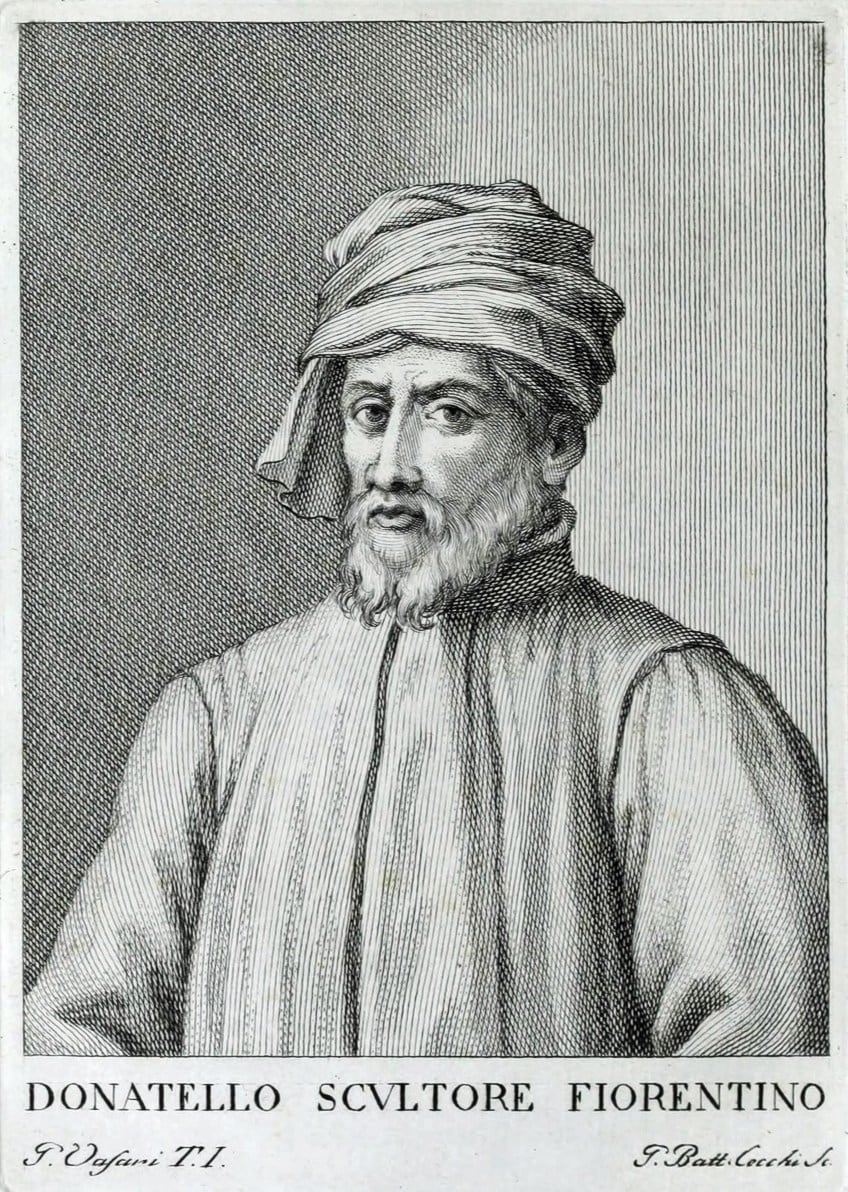

Donatello – Pioneering Renaissance Painter and Sculptor

What was Donatello known for and what were Donatello’s accomplishments? Unlike many other great painters of his time, Donatello the artist did not devote his whole adolescence as a workshop assistant to a master. Donatello’s sculptures pioneered a novel portrayal of motion in apparently immobile stone. Donatello’s works, however, were not limited to bronze and stone; he also created carved wood figures.

The Biography of Donato di Niccolò di Betto Bardi

| Nationality | Italian |

| Date of Birth | c. 1386 |

| Date of Death | 13 December 1466 |

| Place of Birth | Florence |

Donatello would go down in history as the most important artist to resurrect classical sculpture from the abyss of antiquity, thanks to a revitalized style that broke away from the flat iconography of the Gothic period. He broke innovative ground by implementing new aesthetics in line with the prospering Renaissance Humanism movement of the time – a revolution that underscored a break from medieval theology and preferred deep immersion in the humanities, culminating in the art that looked beyond the secular context of religion to start exploring man’s position in the natural world.

Donatello was one of the most prominent sculptors in Italy in the 15th century, as well as one of the first forerunners of the Italian Renaissance, because of his distinctive, lifelike, and intensely emotive paintings.

Childhood

Donato di Niccolò di Betto Bardi is assumed to have possibly been born in Florence in 1386. The date is based on a statement of revenue given by the artist in 1433, in which he stated his age as 47. He was educated as a youngster at the home of the Martelli family, counted amongst Florence’s wealthiest families.

Donatello the artist’s father was a member of the Arte della Lana wool guild, one of Florence’s seven main guilds in the 14th century.

Florence’s government was ostensibly democratic, with guilds having a major part in the city’s administration. The guild’s headquarters were connected to the Orsanmichele church by a gallery, which was funded by the guilds of the city. One of Donatello’s most significant commissions would be the church’s external adornment.

Early Training and Work

Donatello, similar to some other Florentine artists like Benvenuto Cellini and Lorenzo Ghiberti, received his initial creative instruction in a goldsmith’s workshop. He earned his first significant recognition as an artist when he joined the legendary 1401 competition for the building of the Baptistery doors in Florence. Following that, he worked for a short time at Ghiberti’s studio, the champion of the Baptistery door competition, whose prominent workshop trained a lot of young painters.

Donatello trained with colleague Brunelleschi between 1402 and 1404. According to Brunelleschi’s historian Antonio Manetti (who published his narrative during both artists’ lifetimes), the two traveled to Rome to unearth and study old ruins.

Around this time, the Humanist philosophy in Florence started, emphasizing artistry from ancient Rome and Greece over the strict and formal styles of the Medieval and Gothic eras. Donatello and Brunelleschi were among the first to use old ruins as a source of inspiration. Donatello supported himself throughout this period of creative experimentation by working as a goldsmith. Vasari narrates the narrative of Donatello making a wooden crucifix for the Santa Croce church, despite some historians doubting the dates.

The vivid and moving painting showed Christ as a genuine rather than idealized figure, with emotional intensity and expression that contrasted sharply with the time’s bland iconography.

This was groundbreaking, and it would become a hallmark of Early Renaissance painters. Brunelleschi interpreted this as Donatello carving a peasant. To improve, he crafted his personal wooden crucifix and invited Donatello home for supper, casually displaying his work “in a nice light.” Donatello entered and dropped the meal he was holding, prompting Brunelleschi to inquire, “Donatello, what are you up to? How are we going to eat now that you’ve left it all behind?” Donatello said, “Then take whatever you desire if you want it. It is given to you to do God’s, and it is given to me to do beggars.”

Donatello began to get additional substantial orders after the successes of this artwork, including two monumental statues for the guild Orsanmichele church, which had been a vital part of his youth.

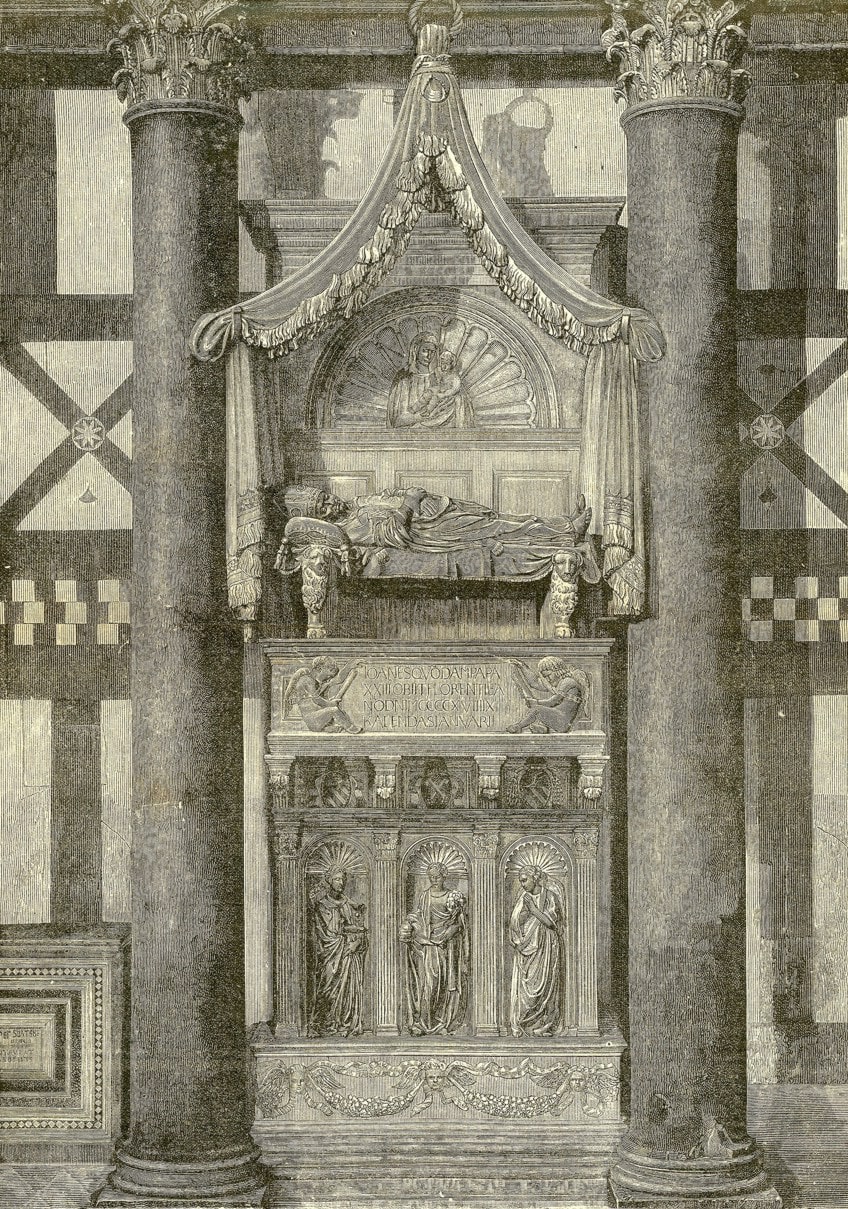

He was the first sculptor during this timespan to use new skills and techniques obtained from the Early Renaissance era’s integration of math and science, and architecture into art, such as one-point perspective and anatomical precision, and he even formed a trademark type of bas-relief for his sculptures to highlight depth and three-dimensionality. He also cooperated with other painters, like Michelozzo, with whom he created a burial monument in the Baptistery of Florence.

Mature Period

Around 1430, Donatello came under the sponsorship of Cosimo de’ Medici, the patriarch of Florence’s most prominent family, and a well-known patron of the arts. Cosimo ordered the artist to create a bronze sculpture of David, resulting in the world’s first free-standing naked statue. Because of the homoerotic aspects of Donatello’s David, some critics have claimed that he may have been gay.

Donatello never wed or had children, according to what is known about his personal life.

Donatello had eroticized ties with his apprentices, according to accounts relayed to Angelo Poliziano shortly after his death in 1480. A party of opposing families imprisoned and expelled Cosimo de’ Medici from Florence in 1433. In the unavailability of his patron, Donatello journeyed to Rome, increasing the classical influence on his work. The next year, he and Cosimo returned to Florence and resumed work on proposals for the Duomo and the church in nearby Prato. For the artist, this was a period of considerable growth and success.

Late Period

Despite having spent most of his life in Florence, Donatello was sent to Padua in 1443 to sculpt a burial monument for condottiere Erasmo da Narni, also known as Gattamelata. Since antiquity, his equestrian sculpture was the first of its sort. He pushed on traveling to Florence despite Donatello’s artwork’s positive reception in Padua.

He lived his remaining years in Florence, where he established a workshop with trainees and received financial support from Cosimo de’ Medici.

When Cosimo died, according to Vasari, he begged his son Piero to look after Donatello, and Piero agreed, giving Donatello a property near Cafaggiuolo. Despite his initial delight, the artist found the country life to be too domestic for him, so he returned the property and obtained a monetary stipend instead, and “spent the remainder of his life as friend and servant of the Medici without difficulty or care.”

Legacy

Donatello’s advances in perspective and sculpting during the Early Renaissance contributed significantly to the basic foundation of what would become the thriving Italian Renaissance. The first known pieces of Renaissance sculpture were found here, marking a striking break from the later Gothic aesthetic that had previously dominated.

His groundbreaking work, notably in his depiction of the human figure, would influence early Italian Renaissance artists such as Masaccio, whose paintings in the Brancacci Chapel in Florence signal a watershed moment in European visual art.

Donatello also left an indelible impression at Padua, where he worked briefly, notably on Andrea Mantegna (1431-1506), a key character in the Venetian Renaissance’s growth. Nanni di Banco was among the sculptors he influenced and instructed. Vasari, in particular, emphasized Donatello’s historical significance, claiming, “He may be regarded to have been the first to exhibit the art of sculpting among the moderns.” His attraction has lasted for decades, even making its way into popular culture today.

Donatello’s Accomplishments

The renaissance of passion in science, mathematics, and architecture that was going place in Florence inspired Donatello’s work greatly. This included using a one-point perspective to construct a new type of architectural bas-relief and ensuring that his figures were anatomically correct. For the artist, the figure was a major point of expertise, and he was the first to revive nude sculpture.

He created paintings that expressed a genuine realism over the glorified images of the past by adding realistic proportions, emotions, and expressiveness to his themes, whether legendary, historical, or daily people.

Donatello was a multi-media artist who worked with stone, metal, stucco, wood, clay, and wax. Among contemporary painters, he was the first to depict the art of sculpture. His adaptability and resourcefulness would serve as a model for many future sculptors interested in exploring new material possibilities.

The Most Notable Donatello Artworks

When thinking about Donatello’s works, it is not really Donatello’s paintings that come to mind. Rather it is Donatello’s sculptures that we are all more aware of. Let us take a look at some of the most appreciated examples of Donatello’s works.

Saint John the Evangelist (1415)

| Date Completed | 1415 |

| Medium | Marble |

| Dimensions | 1.36 m (height) |

| Current Location | Museo dell’Opera del Duomo, Florence |

Although the exact date of this early artwork is unknown, the sculptor labored on this large-scale marble statue representing Saint John the Evangelist between 1408 and 1415. Donatello opted to represent the apostle as an aged prophet clutching the Bible, a break from mythology, and a more humanizing portrayal. The statue’s facial expression is well examined, and the modeling of the hands and legs allude to a more lifelike figuration. Donatello gives close attention to the physiology of the saint’s legs, despite the fact that they are concealed behind his robes, revealing a new interest in expressing the body both accurately and naturalistically.

The sculpture was part of a collective work that gathered together works by several of Florence’s most prominent painters over the span of two centuries in a niche on the Duomo Cathedral’s façade.

This sculpture is considered a significant departure from the Gothic style, which dominated Florentine (and European) art at the time. Furthermore, Donatello demonstrates a new grasp of perspective needs, accounting for the fact that visitors would view the sculpture from below, causing the body to be abnormally longer than the legs.

Donatello was fully cognizant that the base of the statue would be set roughly four feet above human height, as Daniel M. Zolli notes: “Not only are John’s ratios far nearer to nature when demonstrated from this angle, but his appearance is far more impressive: the textile of his garbs hangs strongly from the frame of his body, and the whole structure arranges itself into a stable pyramid.”

St George (1416-1417)

| Date Completed | 1416-1417 |

| Medium | Marble |

| Dimensions | 2.14 m |

| Current Location | Bargello Museum, Florence |

Donatello was contracted by the armorers’ guild to sculpt this statue of St. George for an alcove on the facade of Florence’s Orsanmichele cathedral. The piece is a life-sized representation of the saint standing on a marble panel depicting the renowned fabled event when George killed the dragon.

Although Donatello’s painstaking representation of the emotionality of the face exposes a certain weakness and tenderness, the piece was intended to reflect the Florentine character of standing firm against all opponents.

This skill in conveying emotion, as demonstrated in his horseback statue of condottiero Erasmo da Narni, was the artist’s distinctive style for humanizing subjects who were normally depicted in a more idealized manner.

The work is significant in the evolution of sculpture because Donatello reintroduced classical sculpting standards and coupled them with a new realism, moving decisively from the previous Gothic mannerism. The marble panel at the foundation is also a significant piece of art in and of itself. It is an important early instance of a bas-relief created with the ideas of linear perspectives, which were permeating art at the time.

One of the important discoveries that led to the creation of Renaissance painting was the change from empirical to linear perspective. Donatello would have been aware of Brunelleschi’s studies with perspective, and his expertise was to adapt them to the difficult medium of bas-relief sculpture.

Bust of Niccolo da Uzzano (1433)

| Date Completed | 1433 |

| Medium | Painted terracotta |

| Dimensions | 46 cm |

| Current Location | Bargello Museum, Florence |

Niccolo da Uzzano was a prominent player in Florentine politics in the early 15th century, serving as a trusted conduit between the city’s major competing families. Donatello created the bust shortly after Uzzano’s death in 1433 (though its authorship is frequently disputed). Since antiquity, it was the very first half-bust of a private individual manufactured.

Donatello’s use of skillfully molded terracotta clay, the peculiar facial expression, and the application of polychrome paint all indicate that this was supposed to be an authentic picture of a person, rather than an idealized figure symbolizing an abstract notion of leadership or virtue. Donatello’s style emphasizes Uzzano’s humanity and personality in a way never previously seen or felt believable in art.

Nevertheless, alongside the Humanist movement in Florence, artists were shifting to a more truthful picture of humans, whether royal or plebian, that highlighted genuine feeling.

Irving Lavin, a Florentine Renaissance specialist, believes that displaying the figure as a half-bust is crucial to its strength and underlines Donatello’s unique technique. Donatello implies that this is a true portrait, and an imitative depiction of an actual human being, by having cut off the figure at the bust and attempting to avoid conventional exhibition on an elaborate plinth: “The random amputation particularly implies that what is viewable is part of a bigger whole, that there is more than actually meet the eye.”

The Renaissance bust portrays the full individual – that sum total of physical and mental features that make up the “whole man” – by focusing on the top half of the body while consciously highlighting that it is merely a segment.

Cantoria (1439)

| Date Completed | 1439 |

| Medium | Marble |

| Dimensions | 348 cm x 570 cm |

| Current Location | Museo dell’Opera del Duomo, Florence |

Brunelleschi, Donatello’s friend, was finishing his grandiose designs for the dome of Florence Cathedral in the early 1430s. The Opera del Duomo, the entity in charge of decorating and maintaining the structure, focused on interior décor. They employed Luca Della Robbia to create one of the interior organ lofts and subsequently commissioned Donatello to create the other after returning from Rome in 1433. Donatello’s project stood in stark contrast to della Robbia’s. Where Della Robbia divided the Cantoria’s panels into discrete settings, showing the various passages of Psalm 150, Donatello’s was a seamless story that wrapped around the loft’s three sides.

This gave the spectator a sensation of liveliness and movement.

His art was also unusual since it was inspired directly by the classical friezes and ancient sarcophagi he saw in Rome. Donatello’s skill of sculpture and his hallmark methods, honed to alter the visual experience, are also evident in the piece. “The sculptor’s arrangement took carefully into account his Cantoria’s main light source: a few feet below the piece was a collection of torches and candles artfully placed atop an architrave,” art historian Timothy Verdon writes.

Instead of polishing the marble to a gloss, Donatello left certain areas rough so that when illuminated by candles from below, diverse shadows, textures, and points of brightness would add to the overall composition.

It’s remarkable that Donatello spent such care with the materiality of marble in this piece, given it was his final big assignment in this media.

David (1443)

| Date Completed | 1443 |

| Medium | Bronze |

| Dimensions | 158 cm |

| Current Location | Bargello Museum, Florence |

Donatello’s most renowned work is this little yet magnificent bronze. It’s a five-foot-tall bronze statue of David from the ancient biblical account David and the giant Goliath. Instead of a mighty man, he is shown as a young, naked child wearing an odd cap wreathed with laurels (a triumph emblem) and a pair of lavishly gilded boots.

This unusual arrangement, along with the person’s long hair, delicate features, and thin form, creates a provocative, coquettish, and effeminate work of art.

Another oddity is that one of the wings of Goliath’s headgear is far longer than the other one, pointing up the statue’s leg to the crotch. The sculpture has been a focal point for debates over Donatello’s sexuality. Aside from these theories, Donatello’s David is significant both technically and in regard to the artist’s presentation of his subject matter. This was the first free-standing naked statue of a man made since antiquity.

Beyond the daring reappearance of the naked in art, art historian Dr. Beth Harriet observed that “sculptural figures have at last been freed from architecture and now are finally once again autonomous in the same manner that they had been in ancient Greco-Roman times. And since he is self-contained, he is more human, more real. He appears to be able to move around in the globe, as does the contrapposto. This figure is easily imagined in the Medici palace garden, encircled by the ancient Greek and Roman artwork that they were also acquiring.”

Indeed, the diminutive scale and position of the monument were intended to create an intimate encounter for family visitors.

Magdalene Penitent (1455)

| Date Completed | 1455 |

| Medium | Painted Wood |

| Dimensions | 1.88 m |

| Current Location | Museo dell’Opera del Duomo, Florence |

One of Donatello’s most touching works is his life-size representation of Mary Magdalene traveling through the desert in penitence. The artist’s degree of naturalism and emotionality was unmatched. Donatello deviated from mythology and established conceptions about his topic, depicting Magdalene as an elderly, hungry lady rather than the more frequent young and beautiful nude nourished by angels, as he did in many of his paintings.

He draped her in her own hair or a hair garment, indicating the utter repudiation of her previous life as a prostitute.

Despite the fact that, as art historian Bess Bradfield points out, “the saint’s raw body is exposed as much as it is veiled by this hair.” Donatello stresses the humanity of biblical characters in this piece, portraying Mary Magdalene as a sympathetic woman to be mourned and revered on both a human and a holy level.

Donatello’s ability with many materials is demonstrated by his use of wood, and in this beautiful decision, the grain of the wood serves to depict the tortured texture of the saint’s flesh.

The piece was also painted, which added an incredible amount of detail and realism, particularly in the whites of the eyes and pupils. “A figurine from Donatello’s own hands can be viewed, a wooden Saint Mary Magdalene, which is quite lovely and well accomplished, for she has frittered away by abstinence and fasting to such a degree that every part of her body represents a complete and perfect knowledge of human anatomy,” said Giorgio Vasari, who saw the work when it was displayed in Florence’s Baptistery.

Interesting Donatello Facts

So far, we have covered Donatello’s biography and artworks. There are, however, even more interesting facts to learn about his life. Below is a list of some of our favorite Donatello facts.

Donatello Promoted a Novel Way of Expressing Motion in Ordinarily Inert Stone

Figura serpentinata is the Italian term for this style, which depicts figures in dynamic, whirling stances. Contrapposto, a sort of posture utilized by sculptors, is similar but not the same. Following artists like Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael, and Michelangelo used both techniques to bring their sculptures to life.

Donatello Spent Many Years in Rome Early in the 15th Century

The Renaissance artist did this along with fellow Florentine and goldsmith student Filippo Brunelleschi, excavating for relics and studying the city’s ruins. Donatello gained a reputation as a treasure hunter as a result of this journey.

He then returned to Rome to carve tombs alongside Michelozzo, an artist/architect whom he had met in Ghiberti’s studio.

Donatello, Unlike Today’s Image of a Starving Artist, Achieved Recognition

The artist also received much praise and personal wealth during his lifetime. While his talent, creative vision, and love of invention contributed much, his strong association with the Medici family also helped, supplying him with a steady stream of projects.

Donatello Was Not Well-Liked as a Person

Despite being a recognized artist of his day, he was known to destroy a sculpture rather than sell it to someone he didn’t like. He cherished his artistic independence and developed a reputation for being harsh in society.

The artist didn’t have to worry about the consequences of his antisocial behavior because he was protected by the Medici family.

Donatello Was Securely Positioned in the Cradle of the Renaissance as an Artist in Florence

This was due to three key circumstances around the start of the 15th century. His rich hometown not only had a wealthy merchant elite, but it was also a hub for artists, and its closeness to Rome meant that artists didn’t have to go far to reconcile with classical ideas, subject matter, and methods.

Donatello Worked on Two Bronze Pulpits for the Church of San Lorenzo in His Later Years

Donatello did not finish these sculptures before his death in 1466, despite their spiritual intricacy and mastery of his art. Donatello’s work may still be seen in the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo in Florence, as well as other churches and public areas around Italy.

Recommended Reading

Today we learned about Donatello’s accomplishments and art. There is so much more to learn about Donatello’s paintings and sculptures. Here are some books that we can recommend if you would like to go read up some more about Donatello the artist.

Donatello: Sculptor (1993) by John Wyndham

Donatello: Sculptor is a magnificent, lavishly illustrated biography of one of the world’s finest painters. Donatello was born in humble circumstances in Florence in 1386 and ascended by the power of his own brilliance to be one of the primary fathers of the Italian Renaissance. When he died in 1466, he was buried next to his princely patron, Cosimo il Vecchio de’ Medici – a remarkable indicator of the creative revolution he had sparked.

The moment has come for a new and definitive assessment of Donatello and his work. There has been no similar attempt to exhibit the complete breadth of Donatello’s work since H. W. Janson’s vast inventory of 1957.

- A magisterial, beautifully illustrated study of this great artist

- A fluently written and meticulously researched narrative on Donatello

- The standard work on Donatello for many years to come

Donatello and the Dawn of Renaissance Art (2019) by A. Victor Coonin

Donatello, an Italian sculptor, worked to develop a new style of art that came to characterize the Renaissance. His work was forward-thinking, difficult, and often contentious. Donatello expressed human sexuality, aggression, spirituality, and beauty using a range of fresh sculptural methods and imaginative interpretations. To truly comprehend Donatello, one must first comprehend his changing society, which was distinguished by the move from Medieval to Renaissance style, as well as to an art that was more personal and symbolic of the contemporary self.

Donatello was more than just a man of his time; he helped form the spirit of the eras he lived in and had a significant impact on those who followed.

- A beautifully illustrated book on Donatello's great contributions

- Reveals how Donatello's work heralded the emergence of modern art

- The first thorough biography of Donatello in 25 years

Donatello: The Renaissance (2022) by Francesco Caglioti

A lovely assessment of the Renaissance sculptor’s accomplishments, set in perspective with works by his contemporaries. Donatello: The Renaissance is the first comprehensive biography of the artist in many years, reconstructing one of the finest sculptors in Western art. Donatello (c. 1386–1466) is well known for his extraordinarily sensuous sculpture of David, the first freestanding nude male sculpture since antiquity. He also did reliefs but was most recognized for his round sculptures. This book places Donatello’s inventions in context by comparing them with works by other Renaissance masters.

Donatello, an Italian sculptor, worked to develop a new style of art that came to characterize the Renaissance. His work was forward-thinking, difficult, and often contentious. Donatello expressed human sexuality, aggression, spirituality, and beauty using a range of fresh sculptural methods and imaginative interpretations.

Take a look at our Donatello paintings webstory here!

Frequently Asked Questions

Who Was Donatello?

To truly comprehend Donatello, one must first comprehend his changing society, which was distinguished by the move from Medieval to Renaissance style, as well as to an art that was more personal and symbolic of the contemporary self. Donatello was more than just a man of his time; he helped form the spirit of the eras he lived in and had a significant impact on those who followed. During his life, the artist rose from modest origins as the son of a wool carder to the last burial place next to his lifelong patron, Cosimo di Giovanni de’ Medici.

What Was Donatello Known For?

Donatello promoted a novel way of expressing motion in ordinarily inert stone. Figura Serpentinata is the Italian term for this style, which depicts figures in dynamic, whirling stances. Contrapposto, a sort of posture utilized by sculptors, is similar but not the same. Following artists like Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael, and Michelangelo used both techniques to bring their sculptures to life.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Donatello – Pioneering Renaissance Painter and Sculptor.” Art in Context. May 20, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/donatello/

Meyer, I. (2022, 20 May). Donatello – Pioneering Renaissance Painter and Sculptor. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/donatello/

Meyer, Isabella. “Donatello – Pioneering Renaissance Painter and Sculptor.” Art in Context, May 20, 2022. https://artincontext.org/donatello/.