Contrapposto – What Is Contrapposto, the Famous Classical Pose?

Contrapposto was discovered by the ancient Greeks. The contrapposto definition of the Italian word (Italian Pronunciation: [kontrap’posto]) is “counterpose”. The earliest sculptures that depict the human body in this pose date back to 5th-century B.C.E. The Greek invention of the contrapposto is one of the greatest innovations in figurative art.

The Timeless Beauty of Contrapposto

The classical posing technique is still used today to produce beautiful, lifelikeness in the human figure. After the Greek period, many amazing artworks did not embrace contrapposto. But centuries later, the Italian Renaissance would rediscover and rename contrapposto, ultimately delivering it to us in the present day.

What Is Contrapposto?

The contrapposto definition is a relaxed and life-like standing pose in which the body’s weight is rested on one leg. The figure does not stand stiff and upright but distributes the weight of the body at ease. The classical contrapposto pose requires artists to understand the various counterposed components of the figure.

In a natural standing position, we tend to put our weight on one leg.

If we are on our feet for a long period, we even shift our weight from one leg to the other. The leg that is straight supports most of the weight of the body and is called the engaged leg. The leg that is not weight-bearing and only keeps balance is called the free leg. The free leg side appears more elongated yet slightly bent because it is relaxed.

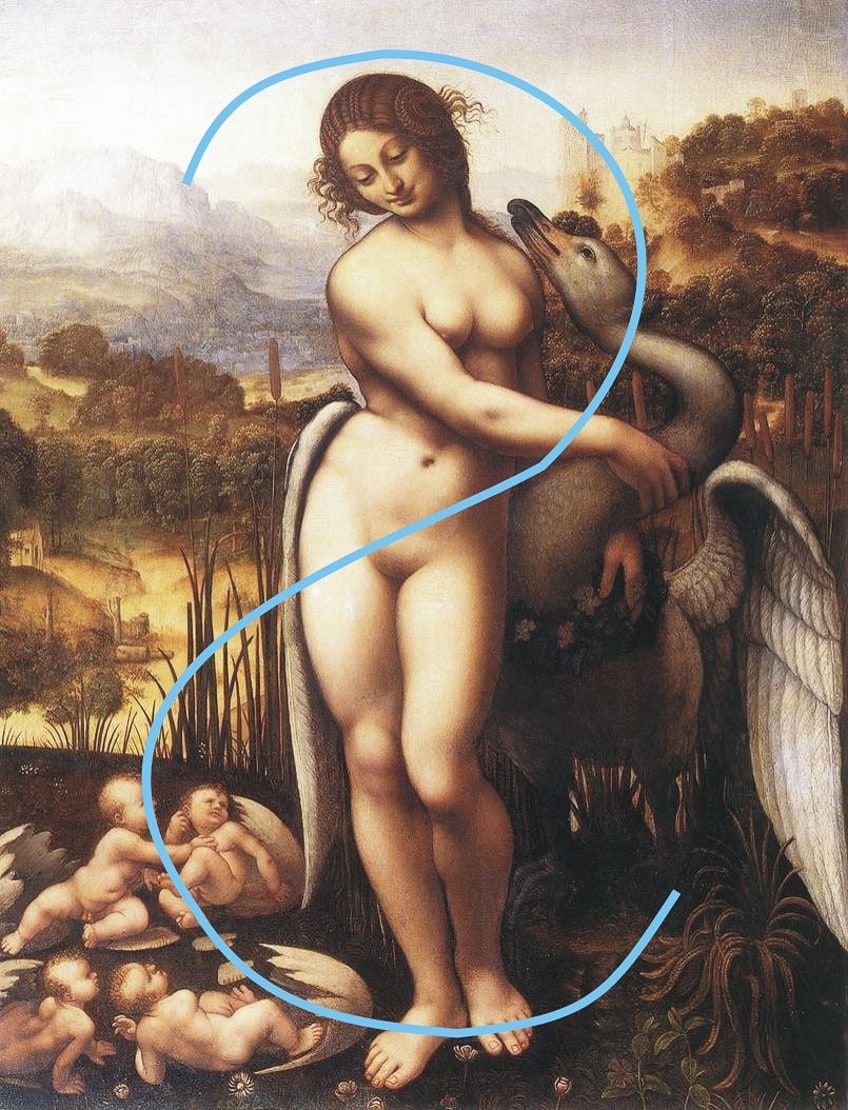

In contrapposto, the shoulders are not parallel to the hips. The pelvis and torso are tilted in opposite directions. The artist must represent the twist of the pelvis and the body’s center of gravity. The hips and rib cage create an “S” curved line along the spine. Contrapposto comes from an anatomic analysis of the body’s alignment when we rest our weight on one leg.

The rational conditions of contrapposto are what make it a dynamic and relaxed pose simultaneously. A contrapposto pose evokes a sense of life through its realistic expression.

The Ancient Greek Origins of Contrapposto

Between 700 B.C.E and 480 B.C.E, the Greek archaic period produced what is known as Greek Kouros sculptures which had almost always been symmetrical, depicting an upright, frontal, and rigid stance. Even when their legs were apart, their weight was evenly distributed on both feet. This was clearly for logistical reasons. Their primary dilemma was keeping the objects upright, so these figures were not yet standing in contrapposto.

This was until what we know as the Greek classical period. This period which began after the end of the Persian wars meant ancient Greece dominated the Mediterranean and European culture. It represented a general flowering of Greek culture and gave rise to rationalism, naturalism, and stoicism in art. Philosophers such as Plato, Socrates, and Aristotle were at work. The great comedies and tragedies were being written. This was the time of the invention of the Olympics and the study of the stars.

Ancient Greece necessitated art that mastered the realities of existence by breaking the stiff symmetry of the archaic Greek figures.

The Greek canon was established in the 5th century at the height of classical sculpture. The canon was a mathematical system of proportions and conventions for the depiction of the human figure. Because of it, the ancient Greeks were the first to create truly naturalistic sculptures of the human body.

Naturalism describes closeness to nature. In figurative art, naturalism was based on a study of proportions, contours, and muscles of the body. It required an understanding of the bones and their movement under the flesh. How the body distributed weight as it moved and how various body parts aided this movement.

The sculptures became more proportionate and there was a great emphasis on the idealized physique.

They would often depict young, heroic, nude, male athletes, gods, or warriors. This allowed artists to flaunt well-defined muscles while employing a naturalistic posture. Often the figures were seemingly doing something when the image happened to be captured. They have the appearance of being frozen in time.

Yet contrapposto’s most animating feature was that it not only affected the legs but the entire torso. With the weight balanced on one leg, the feet were placed in non-symmetrical positions. They had figured out new ways to balance the sculptures without having the feet in an unnatural position. Often, they would include a tree stump or something of the sort to aid in this balancing act.

This allowed artists to create figures which appeared in mid-motion and thus quite real.

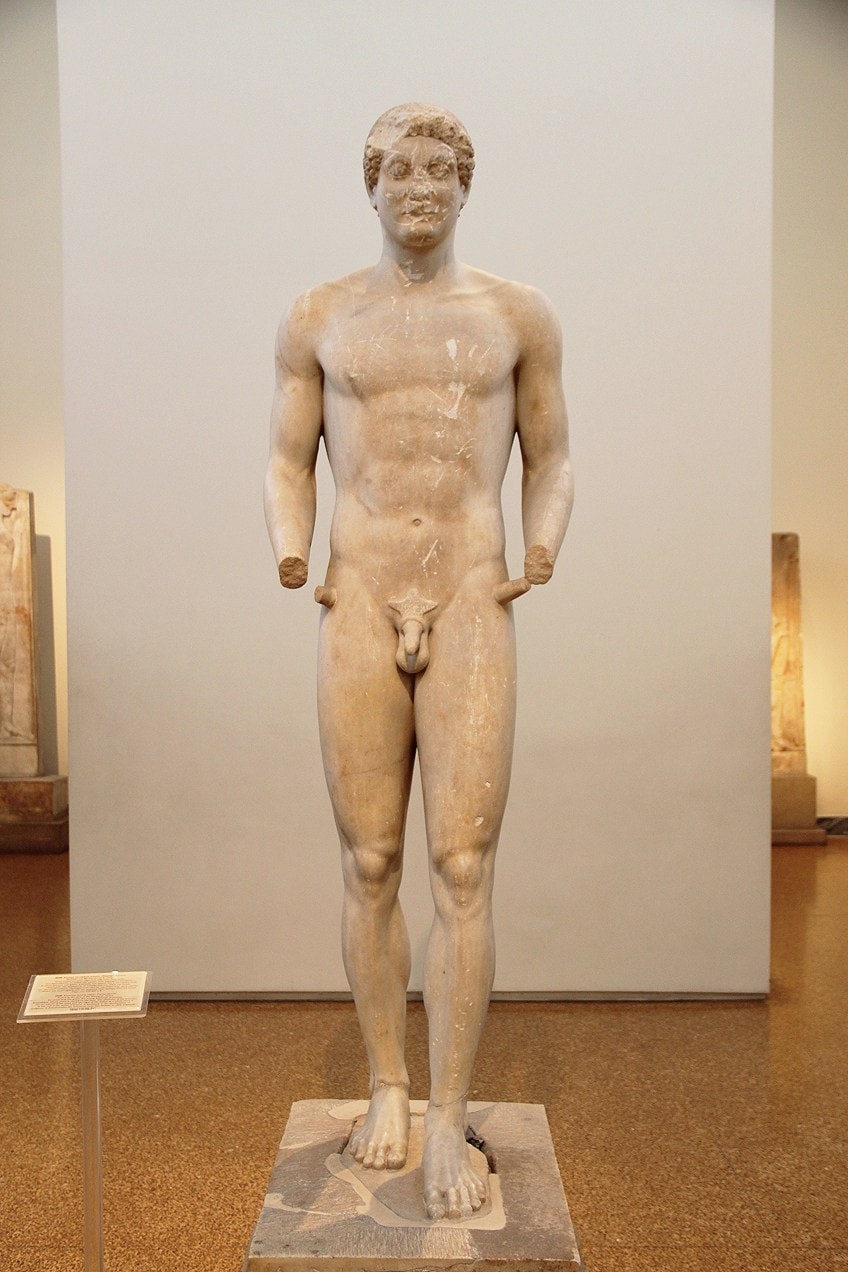

Kritios Boy (c. 480 BC) is the first known example of the use of the contrapposto pose and it was attributed to a sculptor called Kritios. Because very few Greek original sculptures have survived, we know many sculptures through much later Roman copies, but this one is a Greek original. It is likely that contrapposto was being used before Kritios Boy, but this is our earliest evidence.

Polykleitos’ Doryphoros (450 – 440 B.C.E)

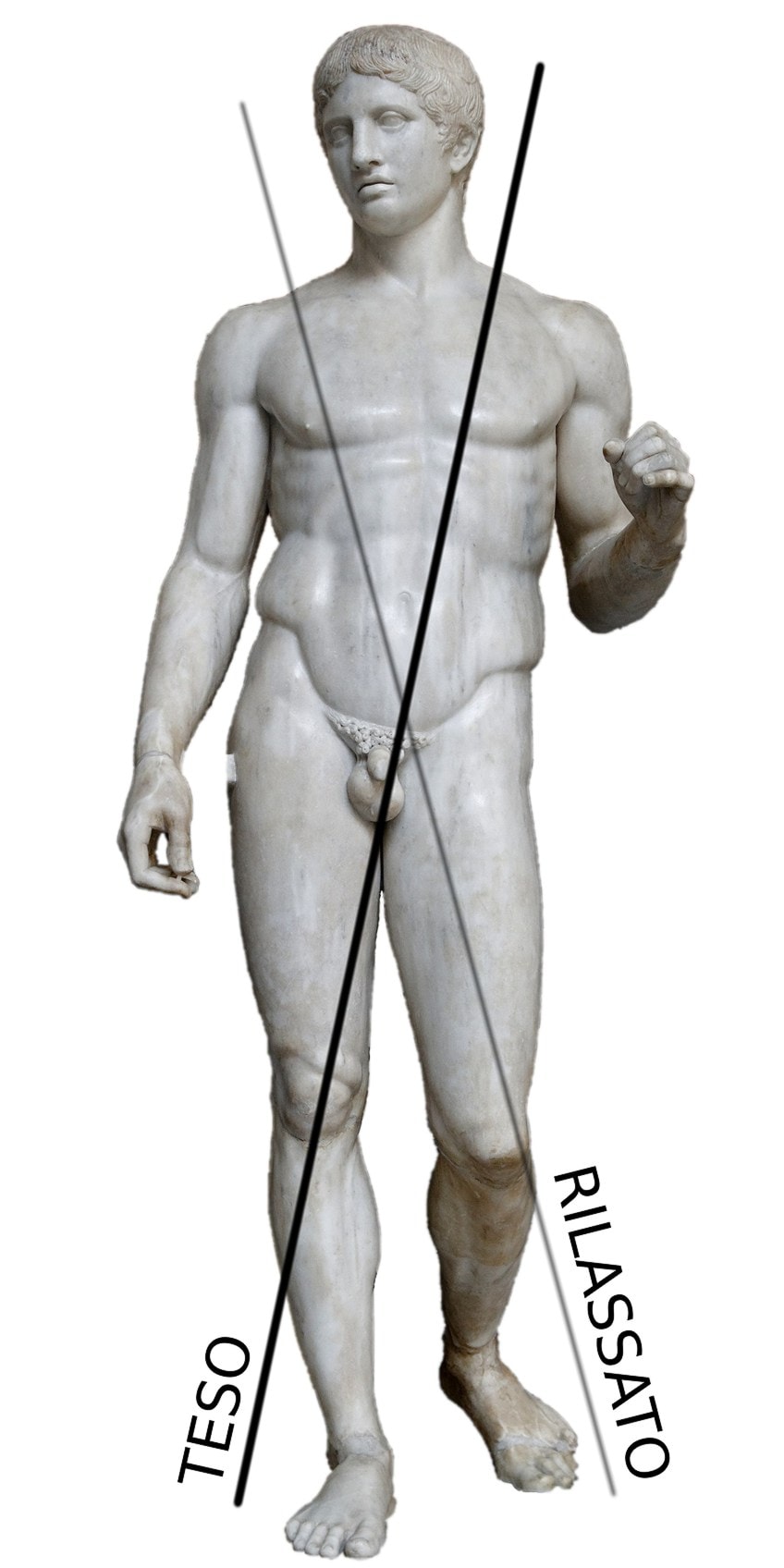

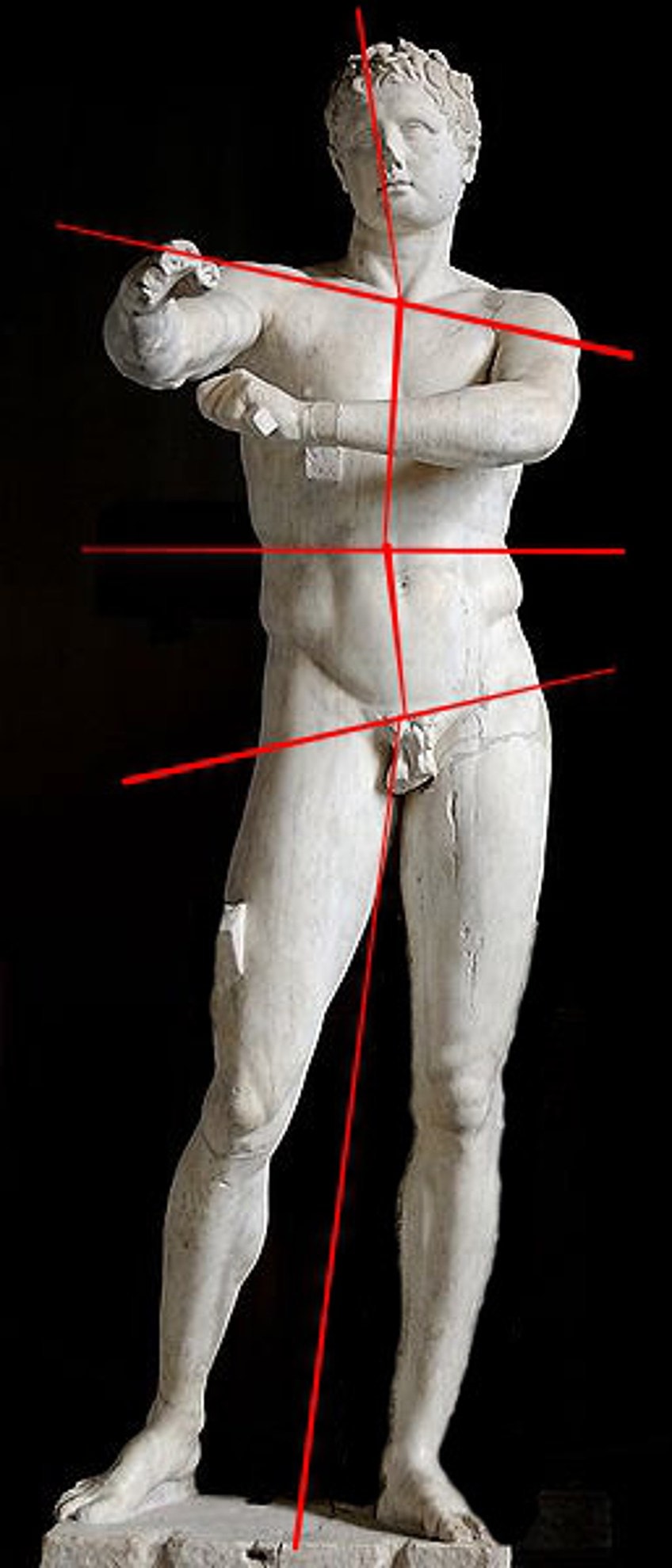

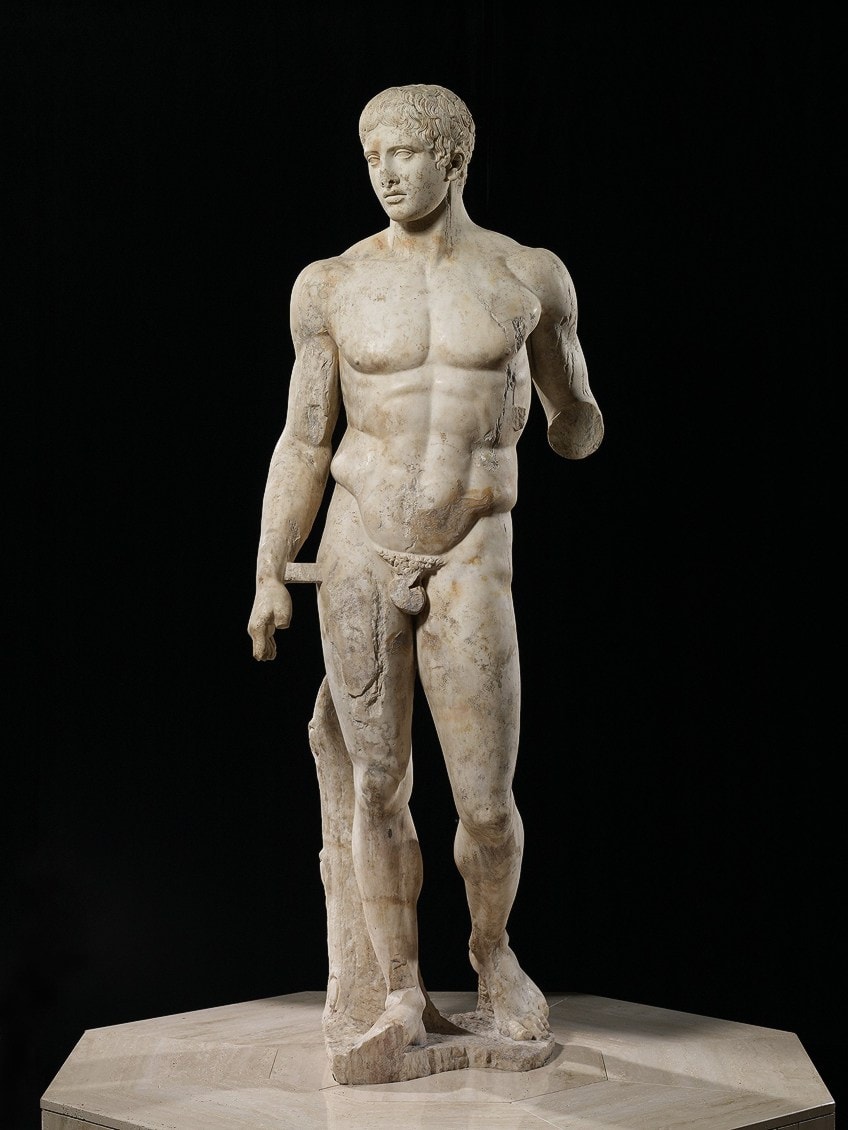

When asking “what is contrapposto?”, it is important to know of Polykleitos, who sculpted Doryphoros or Spear-Bearer originally in bronze. The figure’s hand is up because it probably held a spear at some point, which is now long lost. It is one of the best-known examples of the classical posing technique of contrapposto.

The Doryphoros (450-440 B.C.E) that we often observe is not an original. It is a Roman marble copy of the Greek bronze and a demonstration of how much the Romans were being influenced by classical Greek sculpture. They were the self-proclaimed inheritors of the great Greek traditions of great accuracy to the human body.

It is largely through the Romans that we are now privy to contrapposto.

In contrapposto, Greek figures like the Doryphoros look to the right. The weight-bearing right leg has a hip that juts upward and compresses the side, making it look shorter. The left side where the free leg is allows the hip to hang seemingly causing an extension of the side. The result which is based on the opposition of one side of the body to the other is that there is a dynamic alignment of body parts.

The naturalistic sculpture of Doryphoros indicates a culture based on careful, direct observation where artists were looking at real human figures for their art. Doryphoros, while idealized, is asymmetrical, bringing it closer to an iconic yet naturalistic depiction of the human body. Polykleitos championed this method and stated that a statue should have three major characteristics: “ideal proportions, a balance between tense and relaxed muscles and a balanced orientation of limbs.”

These are the founding elements of the groundbreaking revelation in the representation of the human body that we call contrapposto.

Praxiteles’ Aphrodite of Knidos (c. 340 B.C.E)

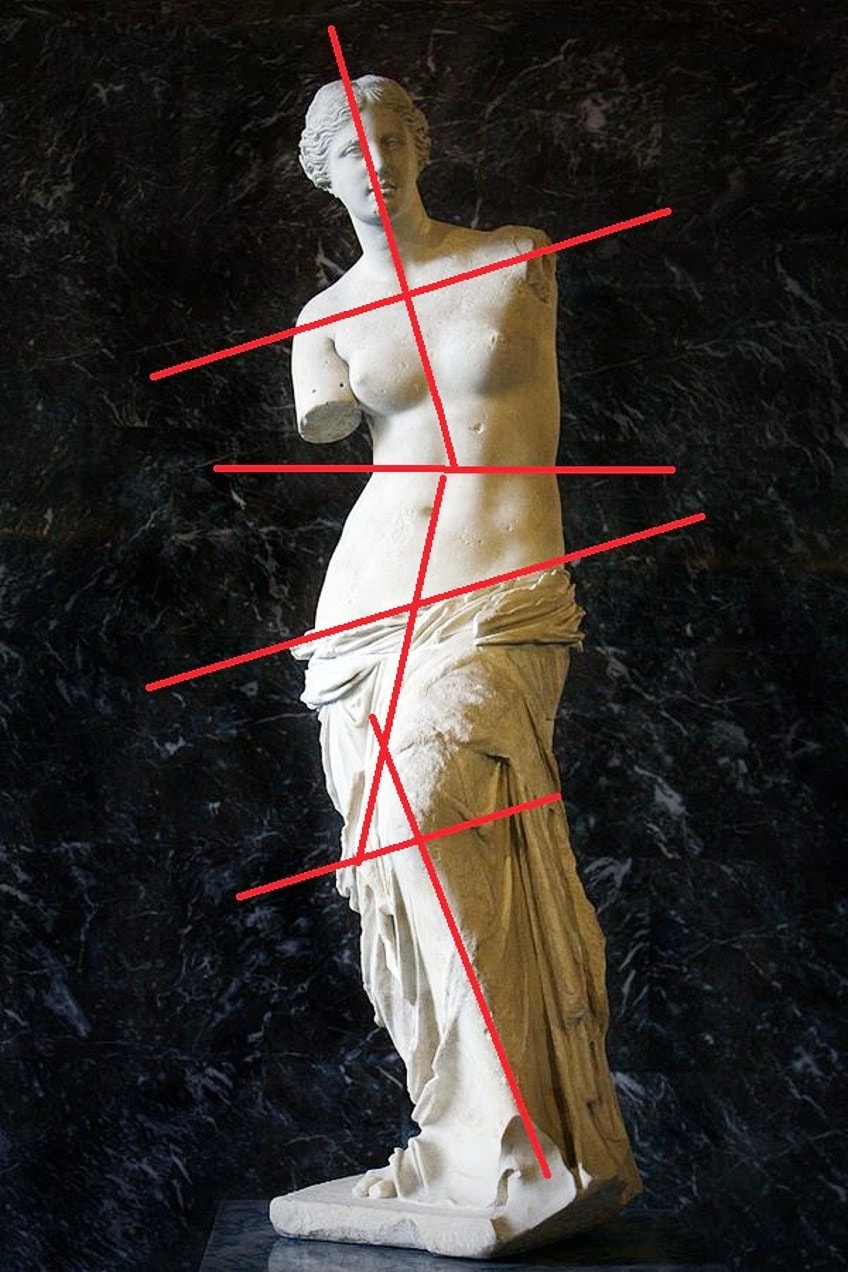

While he’s better known for Hermes Carrying the Infant Dionysus (c. 350–330), Praxiteles also made Aphrodite of Knidos (c. 340 B.C.E) for the city of Knidos which we now know as the Turkish coast. Both these works employed contrapposto. Once again, we only know Aphrodite of Knidos through Roman copies. The copies that exist show a wide variation, so it is not entirely certain what the original would have looked like.

This sculpture is important because it is the first time we see evidence of the female contrapposto pose. Until that point, Greek art avoided female nude statues. Female figures allowed artists to experiment with drapery. They gave drapery motion or a wet look to reveal the form, but they had preferred modesty in female figures.

An artist needed a solid justification for making a female nude. Fortunately for Praxiteles, the goddess of sensuality and love was an appropriate figure to be the first female nude. Because of the mythology around her, Praxiteles’ female nude was accepted and it became such a success that they even put her on their coins.

Aphrodite, who is also the goddess of the sea, is seen in Aphrodite of Knidos in the process of a ritual bath. She seems here to be both goddess and siren. She is positioned in contrapposto, in a flimsy façade of modesty. Her hand covers her private parts while also drawing our attention towards them.

Praxiteles, who was known for his light, lyrical compositions, used contrapposto to accentuate and exaggerate the female form.

His contrapposto has more hip on the weight-bearing leg. There is a more pronounced S curve on the spine. The hip-to-waist ratio was enhanced to illuminate the elegance of the female contrapposto. With this move, Praxiteles created conventions for representations of the female form that have persisted to this day.

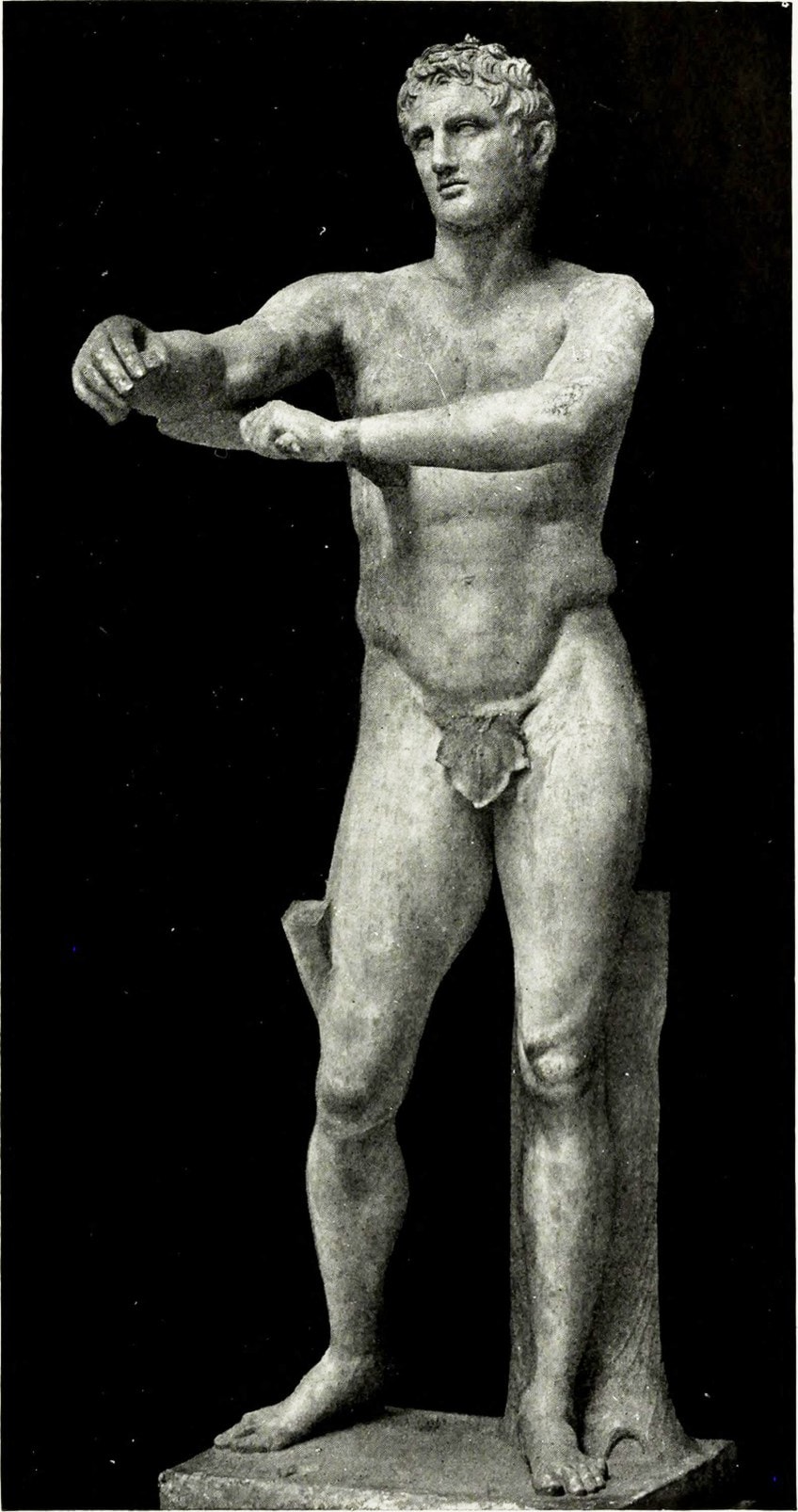

Lysippus’ Apoxyomenos (c. 350 B.C.E)

Many prior sculptures like Praxiteles’ Aphrodite of Knidos were meant to be seen mainly from one angle. Lysippus radicalized sculpture by developing objects with varying focal perspectives. He made work that forced the viewer to move around the sculpture in order to understand it.

Apoxyomenos (c. 350 B.C.E) depicts yet another contrapposto Greek athlete. The title means “the scraper”. Scraping oneself was a common post-workout practice done by ancient athletes. However, if you viewed this sculpture from the front, you would see that the arm is foreshortened.

Lysippus wanted the viewer to walk around the object to see the act of scraping and experience the figure in three dimensions.

The Italian Renaissance (13th century)

After the decline of the Greek and Roman Empires and the subsequent rise of Christianity, artists in the Middle Ages simplified the human figure for the purpose of the narrative. Showing accurately muscular bodies was no longer necessary when the aim was to impart the gospel to the largely illiterate masses.

They had not forgotten Greek artistic practices, but the purpose of art had shifted back from naturalism to spirituality.

For about a thousand years, depictions of the human body were embalmed in a biblical narrative. That is until artists of the Italian Renaissance like Leonardo Da Vinci, Donatello, Andrea del Verrocchio, Nanni di Banco, Michelangelo, and Raphael began to look not only to the figures in the cathedrals of the dark ages but to the naturalism of the ancient worlds. Renaissance is a French word meaning “rebirth”, in this case of Ancient Greek and Roman culture.

Donatello’s David (c. 1440)

Donatello’s David (c. 1440) was the earliest free-standing male nude since ancient times. For the thousand years in between, figures had either been sculpted in relief or clothed. The drapery of their clothing was intended to enhance their otherworldliness, creating rippled patterns that made the figures seem like they were floating or unreal. Donatello’s David stripped back every item of clothing, just like Polykleitos’ Doryphoros.

Unlike the Christian art of the Gothic Age, this was not a rendering that was concerned with the patterning of the drapery but about the mechanical beauty of the human body.

Donatello’s image of David is fairly young as in the biblical story. The scene is set after the slaying of Goliath as David stands in an exaggerated contrapposto pose, hips tilting out with his weight leaning on his right leg. His left leg is relatively weightless and smugly resting on Goliath’s giant head.

Donatello’s David was a radical departure from figurative representations in the Middle Ages and had much more in common with Greek traditions. Interestingly, the nudity and at times overt eroticism began to coalesce with the biblical narrative. The Renaissance poses juxtaposed biblical narrative with the study of the human body. Art once again became about observation in a new Christian world.

Michelangelo’s David (1501-1504)

Michelangelo’s David (1501-1504) has become one of the most well-known sculptures of the Italian Renaissance. It is often used to symbolize the transition from the early Renaissance into the high Renaissance. But this sculpture is partly legendary because of its masterful use of contrapposto. Michelangelo’s David is both iconic and completely at ease.

Michelangelo seems to have synthesized the lessons of Greek art, just like Donatello did, into new Renaissance poses.

His David was made 50 or 60 years after Donatello’s. Michelangelo created tension and dynamism by pushing one mass forward and keeping one behind. The S curved treatment of the figure remains, but Michelangelo’s figure is older than Donatello’s. He has a more muscular physique, and he seems more somber.

He also seems more anatomically sound. His hand is bent, holding what seems to be the sling that hangs over his shoulder. We conclude that it is a sling because we know the story of David. There is no longer a sword or a stone. The narrative references are stripped from Michelangelo’s David. It resembles a figure from Greek mythology much more than a Christo-Judeo figure.

Michelangelo’s contrapposto posed “David” shows that this sculpture is about this artist’s interest in the human form.

There is immense detail in the hair. He makes visible the tendons in the hand, the veins, the kneecap. Its lifelikeness is not encumbered by its largeness. One is able to walk around it and see various details. There is an accomplished delicacy to it.

The Contemporary Use of Contrapposto

Contrapposto is much more than just a standing pose for artists. It has had a massive effect on Western art and thus human culture. It informs our ideas of beauty and permeates our everyday lives. It has been scientifically proven that in Contrapposto figures appear more beautiful to look at.

Artists and advertisers alike use the contrapposto pose to contribute expressive qualities to the human form. It achieves a sense of movement in a still figure. The tension created through potential energy captures a dynamic stillness. It makes the depicted figure feel alive and heightens its humanity.

Attend any decent figure drawing class today and you will encounter contrapposto. Understanding its principles is as important as ever. These skills are not just to make pretty drawings. They teach us about the human body and embed in an artist’s mind the possibilities of manipulating form to suggest movement and life. An artist who masters contrapposto masters the elegant art of harmonizing the components of the human body.

You can also watch our contrapposto web story.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why Were the Greeks the First to Think of Contrapposto?

The Greek invention of the contrapposto was the result of a creative and scientific shift in Greek culture. It tells us that the Greeks had confidence in human capabilities and observations. The culture was self-aware enough to test the boundaries of human skill.

Is Contrapposto for Sculpture or for Painting?

Contrapposto was first and foremost a sculptural development. It is in sculpture that there was a move to make archaic hardened static statues more lifelike. But it informed all areas that require a naturalistic representation of the human figure.

Did Someone Break Michelangelo’s David?

Yes. In 1991 someone took to the masterpiece with a hammer and broke off a piece of its toes.

Heidi Sincuba was the Head of Painting at Rhodes University from 2017 to 2020 and part of the first Artist Run Practice and Theory course at Konstfack in Stockholm, 2021. They completed their BFA at Artez Arnhem in the Netherlands, MFA at Goldsmiths University of London, and are currently a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Cape Town.

Heidi Sincuba’s own practice explores fugitivity through painting, drawing, text, textiles, performance, and installation. This praxis is founded on a conceptual intersection of biomythographic experimentation, existential automatism, and African ancestral knowledge systems. These methodologies of multiplicity result in a fluid and speculative aesthetic, continually manifesting and metamorphosing its material conditions.

Learn more about the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Thembeka Heidi, Sincuba, “Contrapposto – What Is Contrapposto, the Famous Classical Pose?.” Art in Context. February 11, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/contrapposto/

Sincuba, T. (2022, 11 February). Contrapposto – What Is Contrapposto, the Famous Classical Pose?. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/contrapposto/

Sincuba, Thembeka Heidi. “Contrapposto – What Is Contrapposto, the Famous Classical Pose?.” Art in Context, February 11, 2022. https://artincontext.org/contrapposto/.