Trompe l’Oeil – Trompe l’Oeil Painting Techniques With Examples

What is Trompe l’Oeil art and what are a few Trompe l’Oeil examples? Trompe l’Oeil paintings use forced perspective to fool the observer into believing that painted objects or environments are real. Trompe l’Oeil art simulates three-dimensional environments and objects on a two-dimensional plane. This article will explore the history of the Trompe l’Oeil art technique, as well as present a few notable Trompe l’Oeil examples.

What Is Trompe l’Oeil Art?

Shading, perspective, and other methods are frequently used in Trompe l’Oeil paintings to give a sense of dimension and realism. Trompe l’Oeil art dates back to the ancient Greek and Roman eras. It was most popular in Europe throughout the Baroque and Rococo eras, when it was utilized to construct intricate and decorative murals and decorations. Trompe l’Oeil art is still common nowadays, and it is frequently employed in a variety of situations, such as architectural decorations, murals, and even graffiti art.

The History of Trompe l’Oeil Paintings

The term was coined by Louis-Léopold Boilly, a painter, as the name of a piece he displayed in the Paris Salon of 1800. Although the name did not become popular until the early 19th century, the illusionistic approach associated with Trompe l’Oeil paintings dates considerably earlier. It was often used in murals and still is today. There are Trompe l’Oeil examples from Greek and Roman eras, for example, in Pompeii. A common Trompe l’Oeil mural can include a window, door, or corridor, implying a bigger room.

There is an ancient Greek fable about a painting contest between two famous painters. Zeuxis created a life-like still-life picture that caused birds to fly down to nibble at the drawn grapes.

Parrhasius, a competitor, invited Zeuxis to appraise one of his works, which was hidden behind a pair of frayed curtains in his studio. Parrhasius requested that Zeuxis draw back the curtains, but Zeuxis was unable to do so since the curtains were incorporated into Parrhasius’ artwork, which effectively made Parrhasius the winner.

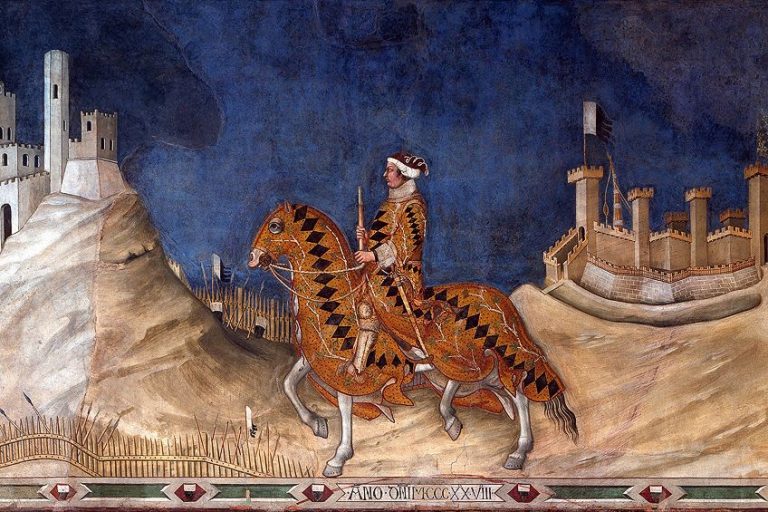

The Use of Trompe l’Oeil During the Renaissance

During the Renaissance, there was an emerging interest in perspective drawing. However, Giotto started employing perspective towards the end of the 1200s with the Assisi cycle in Saint Francis legends. Many late-Quattrocento Italian artists, such as Melozzo da Forli and Andrea Mantegna, started to make illusionistic ceiling works, often in fresco, that used perspective and methods such as foreshortening to give the observer below the impression of more space. This form of Trompe l’Oeil imagery, when applied to ceilings frescoes, is known as di sotto in sù, which translates to “from below, upward”.

The components above the observer are represented from a proper vanishing point of view. Antonio da Correggio’s Assumption of the Virgin (1530) in Parma Cathedral is a well-known example. Likewise, Jacopo de’ Barbari and Vittorio Carpaccio used minor trompe l’Oeil elements in their works, humorously testing the line between illusion and reality. For instance, a painted fly may appear to be resting on the artwork’s frame, a screen may appear to partially conceal the artwork, a piece of paper may seem to be connected to a board, or a person may seem to be leaping out of the artwork entirely – all in reference to Parrhasius and Zeuxis contest.

The Developing Theories from the 17th Century Onwards

Perspective theories of the 17th century enabled a more holistic approach to architectural illusion, which is referred to as quadratura when utilized by artists to “open up” the surface of a ceiling or wall. Allegory of Divine Providence by Pietro da Cortona (1639) and Apotheosis of St Ignatius by Andrea Pozzo (1694) are two Trompe l’Oeil examples from this period. In the 16th and 17th centuries, the Baroque and Mannerist interiors of Jesuit churches frequently incorporated such Trompe l’Oeil ceiling murals, which visually “open” the dome or ceiling to the skies with a picture of Mary’s, Jesus’, or a saint’s assumption or ascension.

Andrea Pozzo’s illusionistic dome of the Jesuit church in Vienna, which is just slightly curved yet provides the sense of actual construction, is an example of a superb architectural Trompe l’Oeil.

Because of the rise of still life painting, trompe l’Oeil paintings were particularly prominent in Flemish and subsequently in Dutch paintings in the 17th century. Cornelis Norbertus Gysbrechts, a Flemish artist, made a chantourné work depicting an easel carrying a painting. Chantourné, which literally means “cutout”, alludes to a trompe l’Oeil image that stands apart from a wall.

In his 1678 work, the Introduction to the Academy of Painting, the Dutch painter Samuel Dirksz van Hoogstraten argued on the function of art as a vivid copy of nature. Trompe l’Oeil may also be found embellished on tables and other pieces of furniture, where a deck of playing cards, for instance, appears to be resting on the table. An impressive example can be found at Chatsworth House in Derbyshire, in which a Trompe l’Oeil painting by Jan van der Vaart from around 1723 depicts one of the inside doors as if it were suspended with a bow and violin.

William Harnett, an American still-life artist active in the 19th century, excelled in trompe l’Oeil. Large trompe l’Oeil murals were produced on the sides of city buildings starting in the 1960s by American Richard Haas and many others, and starting in the 1980s when Rainer Maria Latzke, a German artist, started fusing traditional fresco painting with modern content, Trompe l’Oeil became more and more common for interior murals. The method was used by the Spanish artist Salvador Dalí in a number of his works.

Modern Trompe l’Oeil Artists

Maurits Cornelis Escher, a Dutch artist, was well-known for his optical illusions. One can never be certain of what they are seeing, whether it is a tessellation, a reflection, or a mind-bending picture. Many of his paintings fall under the category of trompe l’Oeil. Richard Haas painted a large artwork on the blank wall of Miami’s Fontainebleau Hotel in the mid-1980s. From 1986 to 2002, the artwork provided the impression that you could stroll directly through the area beneath an intricate arch that went to the beach.

The roughly 6-story artwork was eventually demolished alongside the structure, but Haas’ mural will not be forgotten.

Dutch street artists Deer Feed and Jan Is De Man converted an otherwise nondescript wall in Utrecht, Netherlands, into three shelves of larger-than-life books. They appear to be real from a distance. Lieven Hendriks, a Dutch artist, has a more modern take on the method. Hendriks’ paintings, whether they are nails or finger smudges, make the spectator rethink what they are witnessing. Street painters like Edgar Mueller, Kurt Wenner, and Julian Beever employ perspective to create situations with so much life that it’s difficult to believe they’re not genuinely three-dimensional.

Famous Trompe l’Oeil Examples

Even though the word only gained popularity in the 19th and 20th centuries, Pompeii has evidence of the method dating back to 70 CE. A mix of perspective and chiaroscuro, or the application of dramatic light and shadow to produce depth in their works, is employed to trick the eye in Trompe l’Oeil paintings. Here are a few famous Trompe l’Oeil examples.

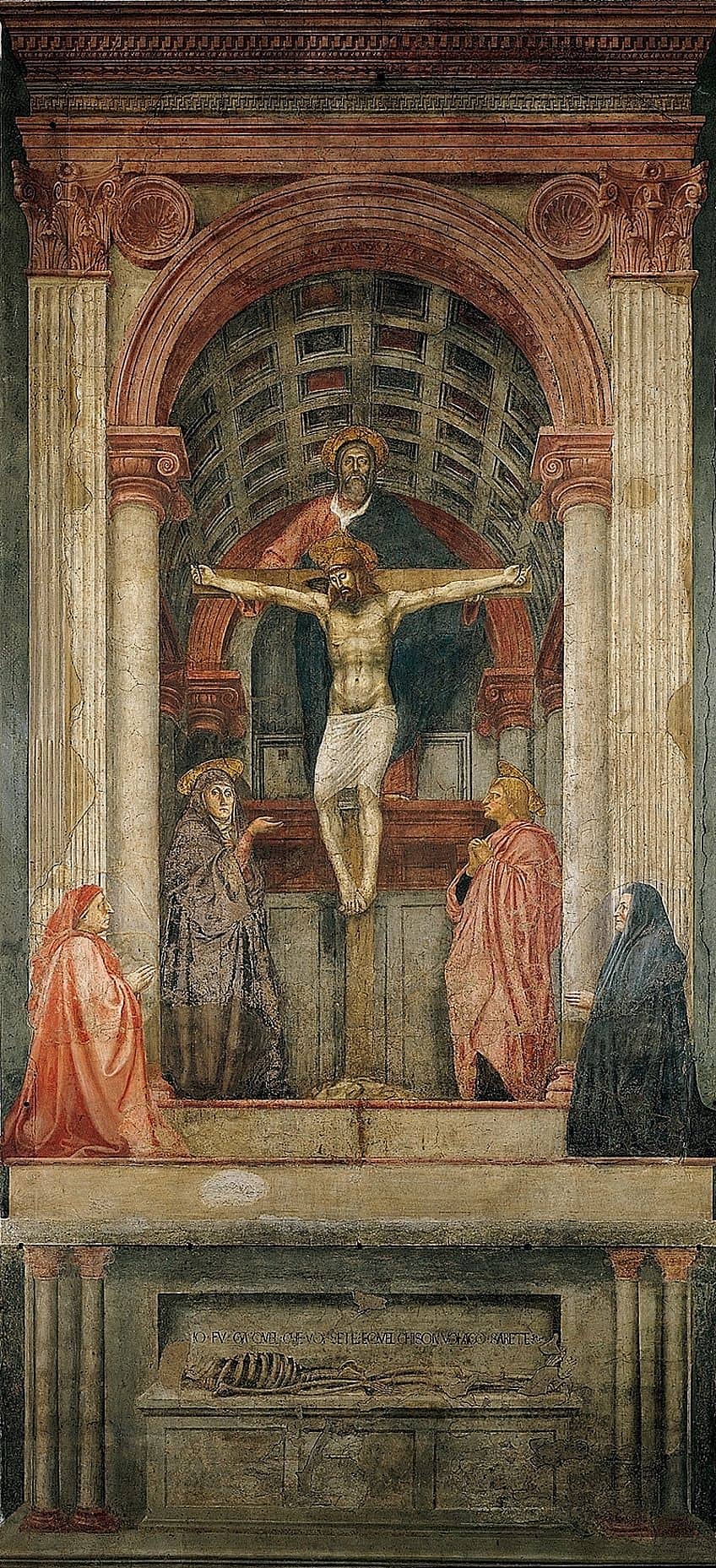

Holy Trinity (1428) by Masaccio

| Artist Name | Tommaso di Ser Giovanni di Simone (commonly known as Masaccio) (1401 – 1428) |

| Date Completed | 1428 |

| Medium | Fresco |

| Dimensions (cm) | 667 x 317 |

| Location | Santa Maria Novella, Florence, Italy |

The fresco is situated in the center of the left aisle of the basilica. There are definite signs that the fresco was aligned very accurately in relation to the vantage points and perspective configuration of the room at the time, especially a former entrance-way facing the artwork, to maximize the Trompe l’Oeil effect, even though the layout of this room has changed since the work of art was produced. Additionally, to emphasize the “realism” of the artifice, an altar was set as a shelf-ledge between the upper and lower portions of the mural. Little is known about the commission; no contemporary documentation indicating the altar-patron pieces has been discovered.

On either side of the archway, in the fresco, are two donor portraits that have not yet been formally recognized.

The individuals pictured are probably contemporary Florentines, either the patrons of the artwork or their families or close acquaintances. They were most likely still alive when the artwork was commissioned, according to the accepted conventions of such depictions, but this is not widely acknowledged. To give the painting a sense of depth and reality, the original design called for a real ledge to be used as an altar and to physically protrude forth from the now-empty space between the top and bottom parts of the painting. The facing edge and top surface mix with the stairs and archway in the fresco, and its supporting pillars, both actual and imagined, work with the overhang’s shadows to create the appearance of a crypt for the tomb below.

Candle smoke and heat effects from the altar’s use are still visible in the top portion of the painting. The artwork is notable for taking influence from old Roman triumphal arches and adhering strictly to recently discovered perspective methods, with a vanishing point at the audience’s eye level. Generations of Florentine artists and touring painters were influenced by the fresco. Orthogonal lines sweep geometrically outward and upward to form the angles and proportions of the barrel vault’s slightly diagonal lines. His utilization of linear perspective creates the appearance of three-dimensional space.

Camera Degli Sposi (1474) by Andrea Mantegna

| Artist Name | Andrea Mantegna (1431 – 1506) |

| Date Completed | 1474 |

| Medium | Fresco |

| Dimensions (cm) | 800 x 800 |

| Location | Ducal Palace, Mantua, Italy |

The Ducal Palace in Mantua, Italy, houses the Camera Degli Sposi, a chamber frescoed with illusionistic Trompe l’Oeil artworks by Andrea Mantegna. The Gonzaga preserved Mantua’s political independence from its stronger rivals Milan and Venice throughout the 15th century when the Camera Degli Sposi was produced, by offering their help as a mercenary state. Ludovico III Gonzaga wanted to give the Gonzaga authority more cultural legitimacy at a period when other Northern Italian palaces, like the Ferrara, were acquiring their own “painted rooms”, so he hired Mantegna to fresco the chamber.

The Camera Degli Sposi is situated on the first story of a northeastern structure of the Ducal Palace’s private area, with windows on the eastern and northern sides facing Lago di Mezzo.

This room would have served multiple private and semi-private roles, including Ludovico’s bed chamber, a meeting place for family and intimate consorts, and a sitting room for exceptionally important guests. The semi-private purposes of the chamber contributed to the Camera Degli Sposi‘s sense of exclusivity, which was supposed to impress viewers with Gonzaga’s riches and cultural prominence without an overt or showy exhibition. The chamber was remodeled before Mantegna started painting to be as near to a square as possible, with measurements of around eight by eight meters wide. The Camera Degli Sposi, painted between 1465 and 1474, became well recognized quickly after its creation as a masterwork in the use of Trompe l’Oeil.

Mantegna’s illusionistic painting, which is reminiscent of a classical pavilion, has subtle variations in perspective points that make each purely fictional part of the illusion appear genuine to the observer. Gathering scenarios of the Gonzaga and their court are shown in front of expansive romanticized landscapes on the western and northern walls, which are enclosed by fictitious marble titles on the bottom and painted curtain rods that extend the total length of every one of the walls at the top.

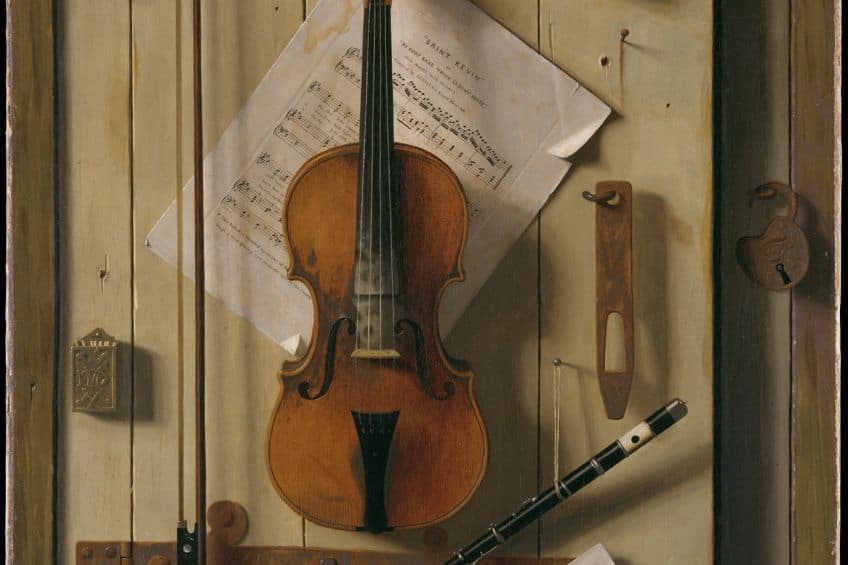

Still Life – Violin and Music (1888) by William Michael Harnett

| Artist Name | William Michael Harnett (1848 – 1892) |

| Date Completed | 1888 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions (cm) | 101 x 76 |

| Location | Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, United States |

Harnett was the most copied and skilled still-life painter in late-19th-century America, known for his many compositions that took the art of trompe l’Oeil to its extreme. While this complicated composition may look flat at first glance, it is rich in depth and elasticity, underlining the conflict between reality and illusion. The hinged door in the illustration is partly open, and the things are hung on conspicuous nails, producing dramatic shadows. Harnett’s sense of humor, as well as his Irish-American identity, are highlighted by the instruments and ripped sheet music for a classic Irish reel.

Harnett’s Trompe l’Oeil painting technique was unusual and inspired numerous imitators, although it was not without precedent. A multitude of 17th-century Dutch artists, such as Pieter Claesz, specialized in astonishingly realistic tabletop still life. Raphaelle Peale, who worked in Philadelphia in the early 19th century, was a pioneer of the genre in America. Aside from his immense skill, what distinguishes Harnett’s work is his interest in showing items that are not typically the topic of a painting.

For generations, artists have pushed themselves and crossed boundaries to deliver stunning works of art to audiences. Trompe l’Oeil painting techniques, for example, have been critical to these attempts. Is there a limit to what may be done, from huge creatures painted in perspective on sidewalks to paintings of drawings attached to a board? The longer artists are allowed to refine and improve on ancient techniques, the more audiences will be impressed, and we will all doubt what is genuine and what is an illusion produced on a flat surface.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is Trompe l’Oeil Art?

Trompe l’Oeil is a technique in art in which the individual creates an optical illusion, making the elements that appear in the artwork look three-dimensional and real in the area surrounding the observer. The method is frequently used to give the illusion of a doorway or entrance opening onto a landscape, or to make things appear to be hanging on or protruding from a wall. Artists have employed this method for ages, and it is still popular today.

When Did Artists Start Using Trompe l’Oeil as a Technique?

Artists have utilized Trompe l’Oeil for many centuries. The method was most popular during the 17th-century Baroque period, when it was employed to construct intricate and opulent murals and paintings designed to dazzle the observer. Trompe l’Oeil is still a common method employed by artists today in a wide range of media, including sculpture, painting, and even architecture. Some contemporary sculptors have employed Trompe l’Oeil methods to produce works that seem to defy physics or to fool the audience into believing they are looking at anything other than art. Many modern painters continue to utilize Trompe l’Oeill methods in their paintings to create the appearance of three-dimensional objects on a two-dimensional canvas.

How Do Artists Use Trompe l’Oeil?

The artist must be adept in painting skills such as shading, perspective, and composition in order to produce a Trompe l’Oeil impression. In order to create a believable illusion of realism, artists must also have a solid grasp of the objects and settings they are illustrating. Trompe l’Oeil can use design and architectural features, as well as painting methods, such as the positioning of items within the composition and the use of perspective to give the impression of depth.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Trompe l’Oeil – Trompe l’Oeil Painting Techniques With Examples.” Art in Context. April 11, 2023. URL: https://artincontext.org/trompe-loeil/

Meyer, I. (2023, 11 April). Trompe l’Oeil – Trompe l’Oeil Painting Techniques With Examples. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/trompe-loeil/

Meyer, Isabella. “Trompe l’Oeil – Trompe l’Oeil Painting Techniques With Examples.” Art in Context, April 11, 2023. https://artincontext.org/trompe-loeil/.