Masaccio – First Italian Master of the Quattrocento

Florentine painter Tommaso Masaccio, known for his artworks such as Madonna and Child with St Anne (1425), is widely regarded as the very first authentic Renaissance artist. The Italian painter’s terribly early death abruptly ended his development, yet Mosaccio’s paintings changed the trajectory of Western art. However, very little is really known about Massacio’s life; yet, we do know that his works, such as the Holy Trinity (1428), were beyond that of any other established artist in the Florentine culture at the time, using a logical perspective that would grow to define the Renaissance period as a whole.

A Tommaso Masaccio Biography

| Nationality | Italian |

| Date of Birth | 21 December 1401 |

| Date of Death | c. 1428 |

| Place of Death | Castel San Giovanni di Altura, Italy |

Italian painter Tommaso Masaccio was ready to take full advantage of the nobility’s enormous funding of the arts during the Early Renaissance, who were eager to flaunt their money and rank by commissioning friezes and altarpieces for their private chapels. He was among the first artists to utilize linear perspective in their works, pioneering methods such as the vanishing point in paintings.

He abandoned the international aesthetic and rich decoration of painters such as Gentile da Fabriano, in favor of a more realistic approach that used chiaroscuro and perspective to achieve stronger realism.

Childhood and Early Years

Tommaso Masaccio was born in a town located close to the city of Florence on the 21st of December, 1401. Both Masaccio and his sibling Giovanni became artists, although none of their parents was artistic. Their grandfather, on the other hand, was a manufacturer of painted wooden cabinetry, and the family surname Cassai originates from the Italian term for “carpenter.” Throughout his creative career, his brother worked on similar pieces.

Masaccio appears to have been artistically oriented since childhood. He was known as “Masaccio,” which translates to “clumsy Tom,” since he paid little heed to society, affairs, or his own personal grooming, choosing to concentrate on his work.

It is uncertain who Masaccio apprenticed under, although it is probable that he did so throughout his adolescence, as was common for young painters at the period. A hundred years later, Giorgio Vasari, an influential art historian, said that “certain figurines made by him in his earliest youth still existed in Masaccio’s village, but any such canvases have already been destroyed.”

Mature Period

In 1422, he entered a professional Florentine painting union, suggesting that he was operating as a freelance painter in the town at that period. The precise date of Masaccio’s relocation to Florence is uncertain, but it might have occurred as early as 1412, on the day of his mother’s second engagement.

Little is known about him until about 1423 when he traveled to Rome accompanied by Masolino, a fellow artist and friend with whom Masaccio would collaborate throughout his career.

There he researched classical sculptures, the features of which he would start to integrate into his paintings as he drifted away from the prevalent Gothic approach at the time. When he returned, he commenced his work on a series of panel altarpieces for Florentine chapels. The arts were booming in Florence just at that period, and Masaccio was introduced to the artwork of great painters such as Donatello and Brunelleschi.

Brunelleschi developed the notion of linear perspective, which had a significant impression on Masaccio’s production, while the effect of Donatello’s sculpting is visible in Masaccio’s older work’s “sculptural” representation of figures.

Late Period

Masaccio’s burgeoning reputation peaked in 1425 when he collaborated with Masolino to create a set of paintings for the Brancacci Chapel in Florence’s cathedral of Santa Maria del Carmine. These massive paintings would emerge to be among the most significant of his career, depicting images from the Scripture that he produced to complement those painted by Masolino. When Masolino went to Hungary during that year, he left the ornamentation to Masaccio entirely. He worked on it for quite some time, often returning to the church in between contracts.

Masaccio began to acquire more notable orders about this period, most significantly for the mural in the church of Santa Maria Novella.

In 1428 Masaccio traveled to Rome when aged only 26, he passed away. The actual reason and details of his death are still completely uncertain. According to one legend, he was poisoned by a competing painter, which is not unlikely considering the strong rivalry of the art industry at the period, however many today suspects that he died of the plague.

In any event, as Brunelleschi put it, Masaccio’s death was “a very enormous loss.”

Legacy

Considering his brief career, Massacio established himself as one of the most influential painters of the Early Renaissance. He is widely regarded as one of the earliest Renaissance artists, and his artworks were analyzed and served as motivation for others who came after him, including Andrea del Castagno, Fra Angelico, and Fillipo Lippi.

His utilization of linear perspective impacted Piero Della Francesca, and later in the Renaissance, Michelangelo, Raphael, and Leonardo Da Vinci were all hugely inspired by his sculptural depiction of the human form.

This Florentine painter is properly regarded as one of the most influential individuals in Western painting history, for bringing the perspective and realism that would characterize Renaissance art and continued to define the art of Western European far into the late 19th century.

Masaccio’s Paintings

The employment of linear perspective to create the illusion of dimension in a two-dimensional depiction was among the most essential innovations in art – and, to a lesser extent, engineering – throughout the Renaissance period. Masaccio was inspired by Filippo Brunelleschi’s architectural designs, who had uncovered the notion of perspective, which had been forgotten since the ancient Greco-Roman eras, and adapted it to painting, changing the direction of Western art.

Masaccio produced art of astonishing realism that was radically distinct from any other painter of the period. He did this by adopting the concepts of perspective of architecture and the analysis of light and shape from sculpture, and adapted them to the medium of paint. His religious images emerge as three-dimensional concrete objects. They inhabit an extension of the audience’s environment, as if behind some kind of pane of glass, rather than a completely different, visual plane, as in Medieval artwork.

Masaccio’s paintings’ realism not only displays the scientific ideas that were crucial to the Renaissance’s growth, but it also pulls the sacred figures closer to the observer and makes them look more human, producing a shift in the people’s relationship with their God.

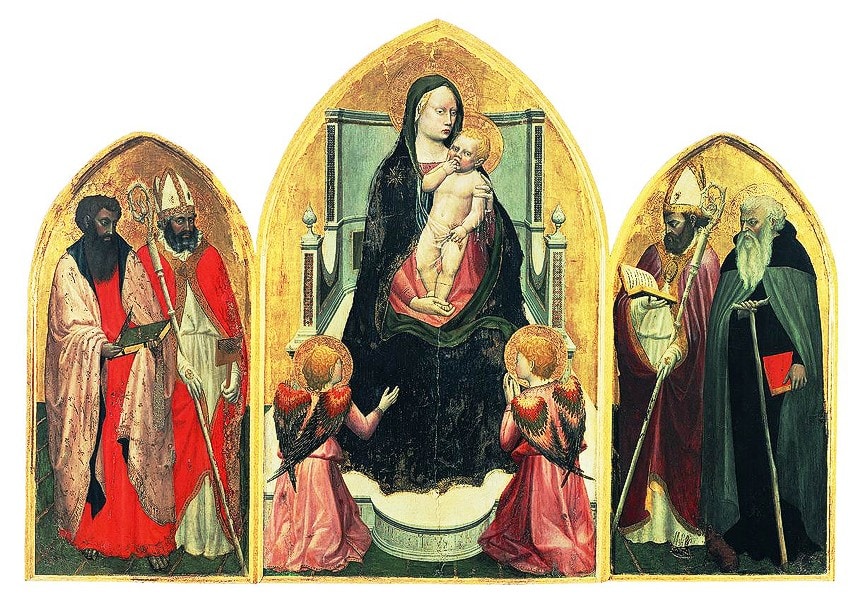

San Giovenale Triptych (1422)

| Date Completed | 1422 |

| Medium | Tempera on panel |

| Dimensions | 108 cm x 65 cm |

| Current Location | Florence, Museo Masaccio |

This is the earliest known example of one of Masaccio’s paintings. With the usual picture of the Madonna and child on its middle panel, it was meant as an altarpiece, likely for a minor chapel of the church. The depiction of the characters demonstrates Giotto’s deep impact, the artist who was at the vanguard of the Renaissance a century before.

The manner in which the Virgin’s seat recedes into the distance, positioning the characters in a realistic realm behind the image plane, though, demonstrates creative use of perspective that was very new for the period.

Masaccio had already been shifting away from the International Gothic aesthetic, abandoning the rich ornamentation and impossible visual space preferred by painters like Gentile da Fabriano and Lorenzo Monaco, as seen by the minimalism of the shapes and arrangement, as well as the natural space. The linear perspective and structural coherence that would come to define his later works may be seen in this early picture.

The bottom inscription is the earliest documented example of contemporary letters being used instead of gothic script.

Madonna and Child with St Anne (1425)

| Date Completed | 1425 |

| Medium | Tempera on panel |

| Dimensions | 175 cm x 103 cm |

| Current Location | Florence, Uffizi |

This painting, which depicts the Virgin and infant again, but this time with her mother seated behind her is likely to be a collaborative work with Masolino. The artwork was initially located close to the entryway to the lodgings belonging to the nuns who were residing at Florence’s church of San Ambrogio. This looks to be a fitting site for this painting focusing on the Virgin and her mother, St Anne, as they were viewed as exemplary Christian ladies. The complex damask cloth held behind St Anne may allude to the panel’s presumed sponsor, Nofri Buonamici, a silk weaver.

While some portions of this artwork retain Masolino’s more Gothic touch, Massacio’s unique painting approach is still visible.

It is most obvious in the Christ child, who is shown as a realistic newborn rather than a Gothic cherub. Masaccio also portrayed the people as though they were lighted by a single genuine source of light to the left, as opposed to the all-encompassing radiance prevalent in Gothic art.

While the rounded figures reflect Donatello’s influence, this panel also shows the evolution of Masaccio’s own distinctive style.

Predella Panel, The Pisa Altarpiece (1426)

| Date Completed | 1426 |

| Medium | Tempera on Panel |

| Dimensions | 83 cm x 300 cm |

| Current Location | Florence, Staatliche Museen |

This is a panel from the bottom margin of the “predella,” an altarpiece created for the cathedral of Santa Maria del Carmine in Pisa. Unfortunately, the altarpiece was dismantled, and only eleven pieces can be definitively ascribed to it to this day. This part depicts two intense and horrific martyrdom scenes from the New Testament. A strip of gold leaf separates each scene. St Peter is bound to a cross on the left. He requested that he be crucified inverted so that he would not be unfairly likened to Jesus. On the right, King Herod’s troops are going to behead St John the Baptist at Salome’s behest.

Masaccio’s mastery of linear perspective may be seen in the image on the left, way down to the foreshortening of St Peter’s halo.

The activity seems to occur in a space behind the image plane, with the figures appearing as concrete three-dimensional things within that space. As they pound in the nails on the cross, the two people on either side of St Peter seem to thrust forward in direction, out towards the observer.

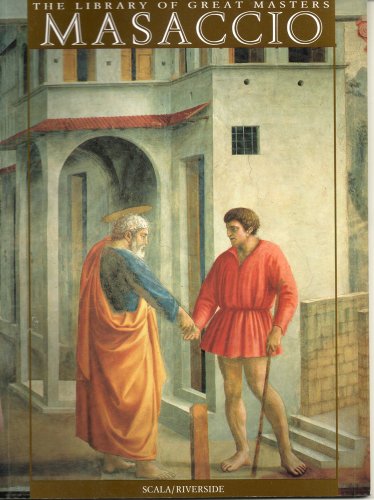

Payment of the Tribute Money (1427)

| Date Completed | 1427 |

| Medium | Fresco |

| Dimensions | 247 cm x 597 cm |

| Current Location | Santa Maria del Carmine |

This fresco picture is one of several representing incidents from St Peter’s life that Masaccio created in conjunction with the artist Masolino in Florence’s Brancacci Chapel of Santa Maria del Carmine. Masolino, who had been engaged on the chapel for some years, finally deserted it, as did Masaccio when he departed for Rome and it was ultimately finished by Filipino Lippi.

Despite devastating fires and modifications by subsequent painters, the frescoes that have survived are regarded as some of the most valuable in Florence.

This portion depicts Christ and his followers at Capernicum, where they must pay taxes. The debt collector confronts Christ and his followers in the center; on the left, the fisherman Peter takes gold from the jaws of a fish as directed by Jesus; and on the side, Peter gives over the payment. This picture demonstrates Masaccio’s deft use of perspective, with ambient perspective in the peaks to the left and linear perspective in the structure to the right, a style that influenced subsequent Renaissance artists. Numerous painters have studied and copied the technical quality of this picture.

Masaccio was among the first artists to integrate realism with perspective in this manner, resulting in a scene that appears more like a pane of a window than a flat surface. The stances of the figures are reminiscent of antique sculptures, and their draped attire is evocative of that donned by traditional philosophers. Even though the artwork has a narrative topic, Masaccio has concentrated on the cohesive arrangement of characters instead of the tale.

According to art historians, the significance of the artwork may be found “in the extent to which figures mirror a cosmic order”. In other terms, the composition represents the equilibrium and organization imparted by God on creation.

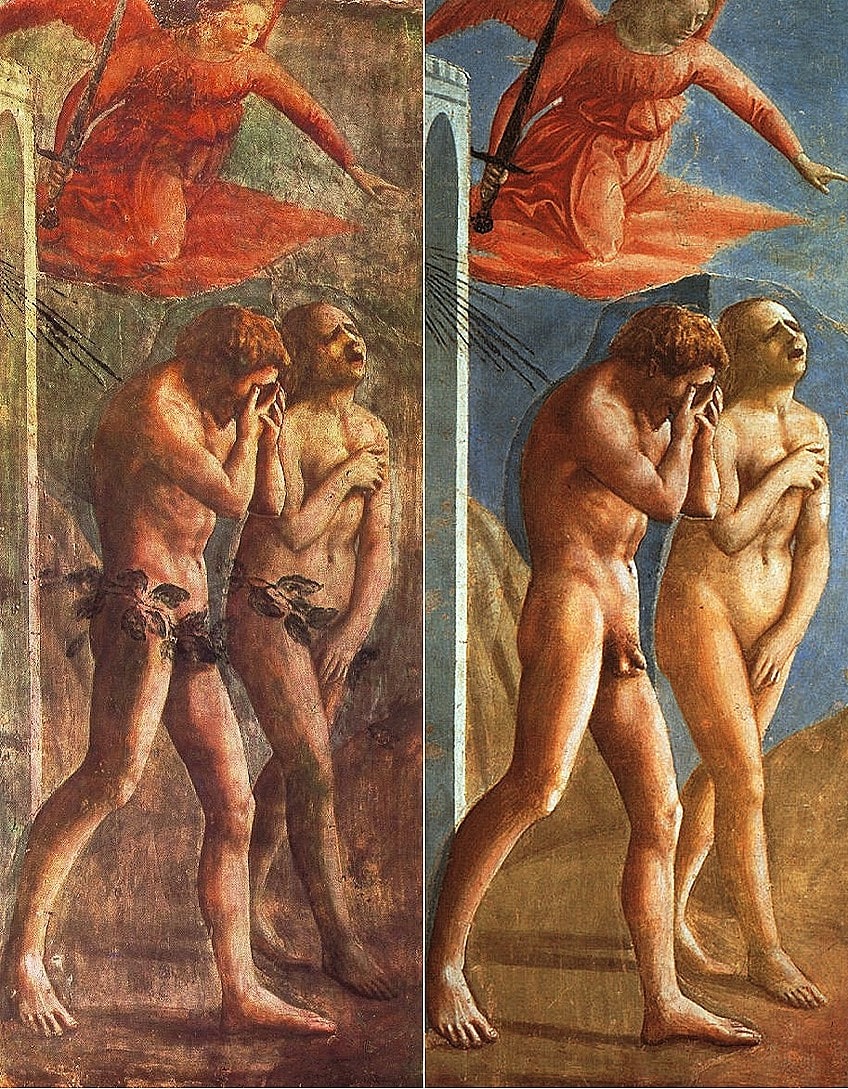

Expulsion from Eden (1427)

| Date Completed | 1427 |

| Medium | Fresco |

| Dimensions | 208 cm x 88 cm |

| Current Location | Santa Maria del Carmine |

This fresco is part of Masaccio’s cycle in the Brancacci Chapel and is one of his most well-known works. It shows Adam and Eve’s expulsion from the Garden of Eden after perpetrating “Wickedness”. Unlike most of Masaccio’s paintings, this mural concentrates on the emotional impact of the subject rather than on space and viewpoint.

The sensation of pain in Adam and Eve’s facial expressions and stances was unique for a scenario that had previously been depicted with serious yet rather expressionless faces in medieval portrayals.

Masaccio’s picture, when compared to Masolino’s painting of the Temptation of Adam and Eve in the very same building, emphasizes the realism of human misery implied in the tale. “I find in it a weird, even spooky hopefulness, that insinuations of beauty may be discovered amongst such suffering,” Sally Munt says about the artwork. This artwork’s new display of passion made it enormously important during the Renaissance, even influencing Michelangelo’s portrayal of the scenario in the Sistine Chapel.

This “beautiful vitality in the semblance of nature,” as defined by Giorgio Vasari, was influenced in part by his study of ancient sculpture. Adam’s body may have been influenced by the renowned Apollo Belvedere sculpture in the Vatican, whilst Eve’s stance is the traditional Venus Pudica, an undressed lady displayed with her hands concealing her nether regions.

The picture reflects Masaccio’s participation in Florence’s emerging humanist movement, which prized the investigation of ancient painters and thinkers.

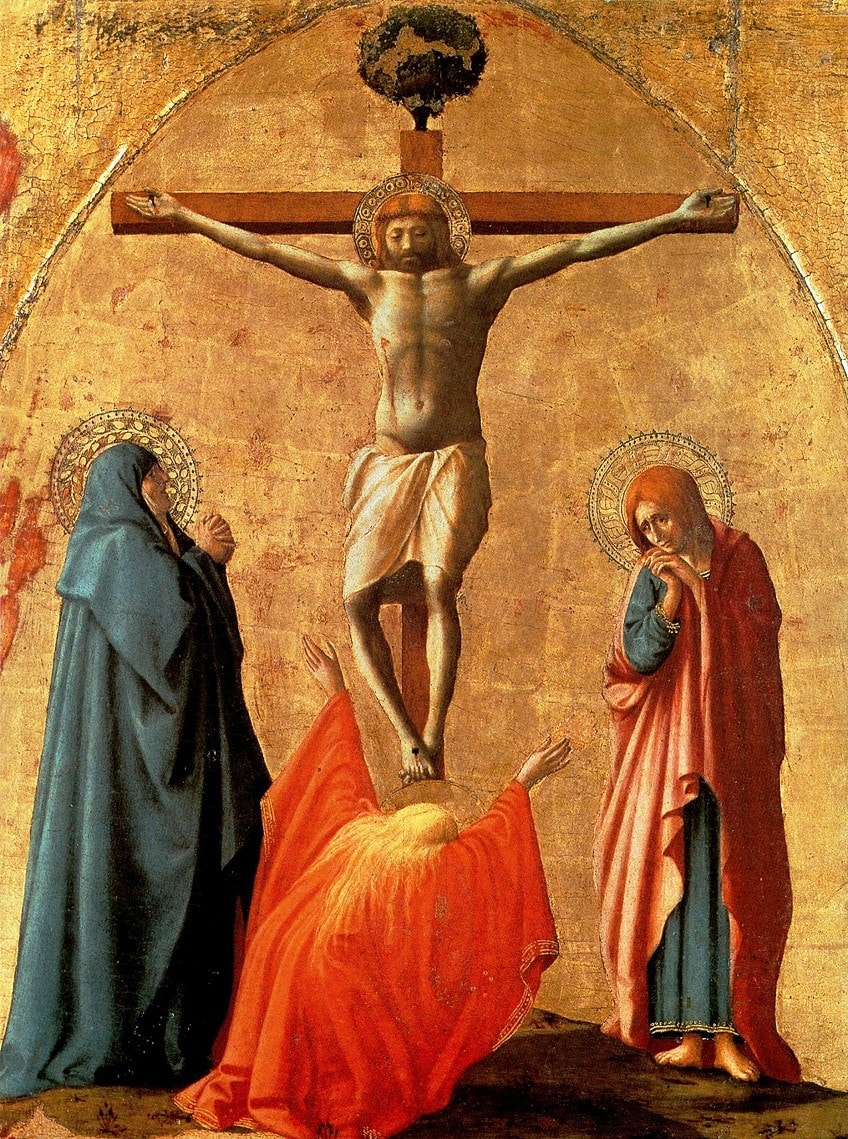

Holy Trinity (1428)

| Date Completed | 1428 |

| Medium | Fresco |

| Dimensions | 667 cm x 317 cm |

| Current Location | Santa Maria Novella, Florence |

This painting, which was produced on the wall of Santa Maria Novella in Florence, is Masaccio’s masterpiece. The clients who commissioned the piece are seen kneeling in the foreground of the picture, but their identities are unknown. The picture represents Christ’s crucifixion, with the traditional images of the Virgin and St John at the base of the cross.

However, the image breaks the Renaissance norm in several ways that it has retained a sense of mystery for centuries, despite being researched by historians.

The work has been named The Holy Trinity because it depicts Jesus with his father behind him and the Holy Spirit as a white dove flying around their heads. Although depicting God figuratively was not a religious prohibition at the time, he would have been represented in a non-earthly domain, symbolizing the skies, rather than in the physical space of the church.

This painting’s representation of three-dimensional space is often regarded as the apex of Masaccio’s technical expertise. The viewpoint is so realistic that current researchers have been capable of creating a 3D representation of the imaginary space described in the picture using digital technology.

Recommended Reading

The Florentine painter Masaccio was indeed an influential artist! Did you gain much new insight into his life based on our Tommaso Masaccio biography? Would you like to learn more about the Italian painter and his works? If so, this list should help you find the best book about Massacio’s paintings and lifetime.

Masaccio and the Brancacci Chapel (1990) by Ornella Casazza

Masaccio was primarily involved in Brunelleschi’s and Donatello’s humanistic avant-garde. Masaccio’s first known picture demonstrates both artists’ proclivity to glorify human value in all aspects and to restore dignity to the vulgar vernacular. Masaccio delves deeply into the works of this painter, focusing on the Brancacci Chapel and other well-known pieces.

- Explores the works of this painter in full

- Concentrates on the Brancacci Chapel and other famous works

- Very informative with images that captivate a dynamic history

Masaccio (1996) by John T. Spike

The narrative strength of Masaccio’s complete body of work is examined in this exquisite anthology, which is powerful and authentic. Masaccio produced a totally naturalistic and emotional manner that launched Renaissance painting in just seven years until his demise at the age of 26. These newly restored frescoes, along with all of Masaccio’s other masterpieces, are shown in spectacular detail in this collection. An introductory essay situates Masaccio in his chronological and art-historical context, stressing the painter’s innovations.

- Explores Masaccio's entire body of work in this elegant volume

- Presents two dozen important paintings in full-page reproductions

- Enlarged details and annotated brief essays for each artwork

That wraps our look at the life and art of the Masaccio. He had a huge effect on other painters and is thought to have started the early Italian Renaissance in artwork with his paintings in the middle-to-late 20th centuries. Masaccio was also among the first to employ linear perspective in his works. Today, just four frescoes are certain to have been painted by Masaccio’s hand, however, many additional works are at least partially ascribed to him. Many of his works are thought to have been destroyed.

Frequently Asked Questions

Who Was Masaccio?

Masaccio was an Italian painter. Born in 1401, he fundamentally altered Florentine art. His work eventually contributed to the development of many of the fundamental philosophical and aesthetic underpinnings of Western painting. Rarely has such a short life been so influential in the annals of art history.

Why Are Masaccio’s Paintings Important?

Masaccio is regarded as a pioneer of the Florentine tradition of art. His massive figures are molded by light, a technique pioneered by Florentine Giotto a hundred years before. Masaccio used it in conjunction with the precise use of linear perspective to create the illusion of credible forms in space.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Masaccio – First Italian Master of the Quattrocento.” Art in Context. April 1, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/masaccio/

Meyer, I. (2022, 1 April). Masaccio – First Italian Master of the Quattrocento. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/masaccio/

Meyer, Isabella. “Masaccio – First Italian Master of the Quattrocento.” Art in Context, April 1, 2022. https://artincontext.org/masaccio/.