Non-Objective Art – Finding a Non-Objective Art Definition

Imagine a painting composed of squares, lines, and just geometric motifs that seem to come from another world, far removed from our own understanding of naturally occurring forms and objects. This is simply Non-Objective art, from this world, which is what we will explore in this article along with some Non-Objective art examples.

What Is Non-Objective Art?

Non-Objective art vs Abstract art often go together, but it can also be confusing to understand. Is Non-Objective art Abstract art? Some sources say it is a form or style within the category of Abstract art, others say it is not synonymous with Abstract art, and others say it is Abstract art – there is a thin line between all of the above.

Below, we discuss the Non-Objective Art definition further, including its origins.

A Non-Objective Art Definition

Non-Objective art is also termed geometric abstraction. According to the definition provided by Tate, it is defined as “a type of abstract art that is usually, but not always, geometric and aims to convey a sense of simplicity and purity”.

If we also look at the definition Tate offers for Abstract art, we will have a better understanding of the non-objective. Abstract art is defined as art “that does not attempt to represent an accurate depiction of a visual reality but instead uses shapes, colours, forms and gestural marks to achieve its effect”.

Indeed, it makes more sense that Non-Objective art is a form of Abstract art, where there are no representational qualities or likenesses to reality; it is completely non-representational. Thus, it is also referred to as geometric abstraction because it consists of geometric compositional motifs.

Abstract art will still have some resemblance to reality, although it will not be an “accurate depiction” like we see from Greek art, as an example, where artists followed the philosophical ideals of mimesis, meaning “to imitate”. This was in the context of imitating nature or reality.

Where Did the Term “Non-Objective” Start?

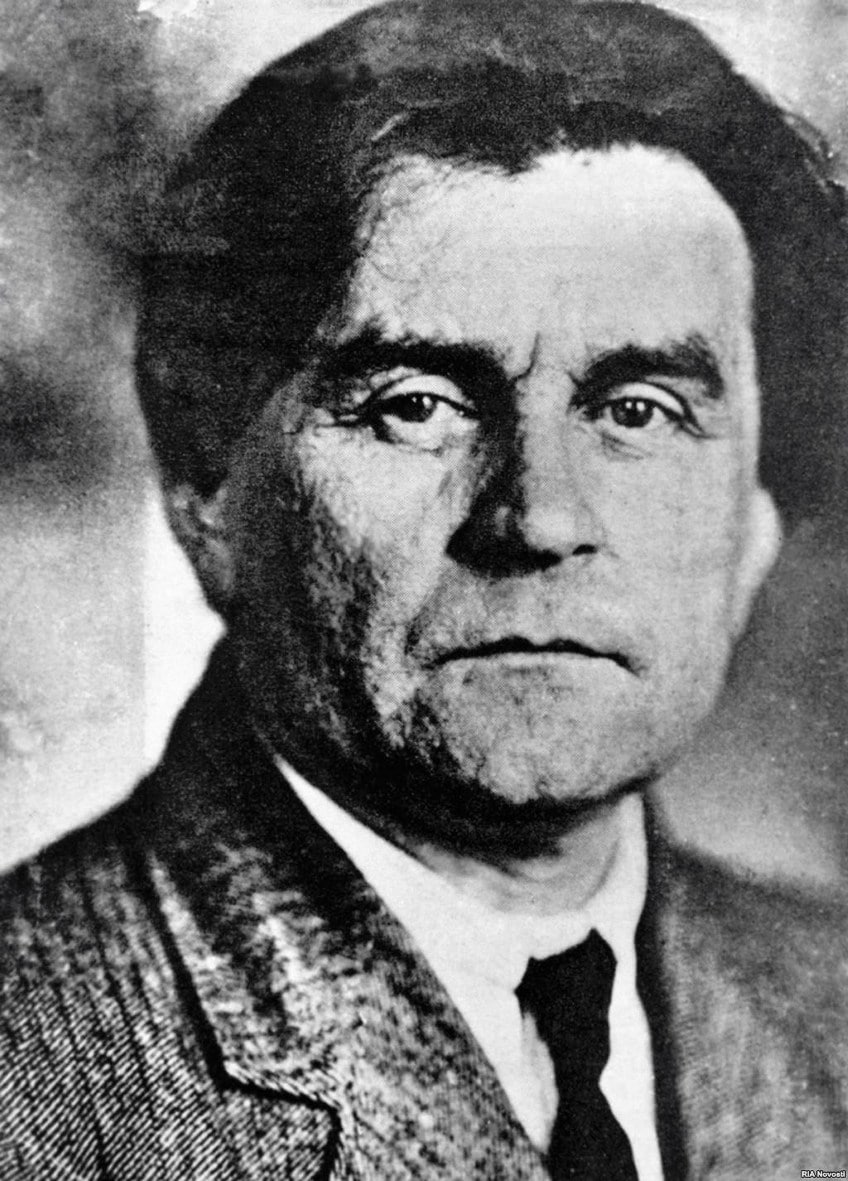

The Russian Constructivist, Alexander Rodchenko, first introduced the term, Non-Objective, when he presented several of his paintings from his Black on Black series, for example, Non-Objective Painting No 80 (1918). Rodchenko co-founded the art movement in 1915 along with fellow artist Vladimir Tatlin. Constructivism as a type of Abstract art movement focused on the “construction” of art instead of the formal compositional qualities that create art.

Art was meant to be constructs of modern industry and serve utilitarian (functional) purposes, and not so much deeper reflections and expressions of inner emotional states.

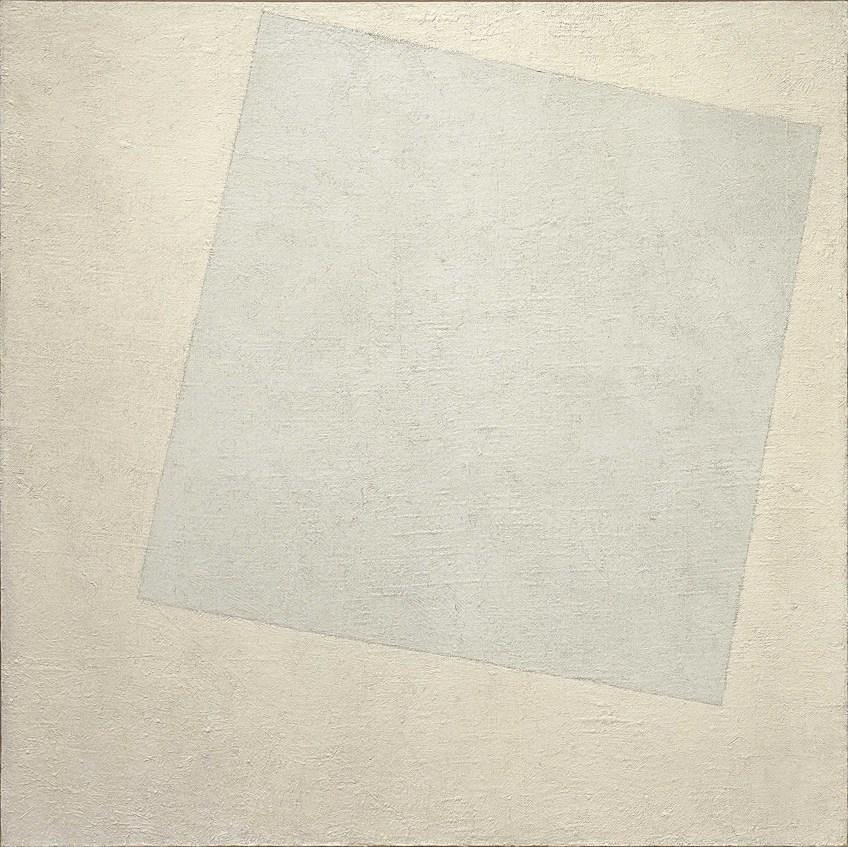

Rodchenko’s Black on Black series was believed to be in response to the artwork by Kazimir Malevich, namely his Black Square (1915). It could have also been a play on Malevich’s White on White (1918). Malevich was the founder of the preceding, and concurrent to Constructivism, an art movement called Suprematism. He founded it in 1913 while still being involved in producing artworks with a Cubo-Futurist style, of which the exhibition, The Last Futurist Exhibition of Paintings 0,10, ushered in the new style of Suprematism, which included Malevich’s Black Square.

The exhibition was held in 1915 by the Dobychina Art Bureau in Petrograd, Russia. Malevich also wrote the accompanying text or manifesto as it also referred to, From Cubism and Futurism to Suprematism in Art (1915). In 1927 he also utilized the term “non-objective” in his publication titled, The Non-Objective World (1927).

A famous quote from the above-mentioned text explains some of the core tenets of Suprematism and that it is related to “pure feeling” and the “visual phenomena” becoming somewhat “meaningless”. They further explain that feeling is the most important “apart from the environment in which it is called forth”.

It was a movement all about going back to the fundamentals of form, a “new realism” as Malevich declared it. It was about the “supremacy of pure feeling or perception in the pictorial arts”. It was the complete opposite of Constructivism and sought to depict a form as it was, in other words, it relied on the formal elements of painting, for example, color, line, shape, and so forth.

However, there was another part to Malevich’s “new realism” and that was tied to a deeper meaning beyond the reality we see. Some sources also suggest it tied in with the spiritual aspects of art. In fact, Malevich was influenced by the esoteric philosophies of the Russian mystics P.D. Ouspensky and Georges Gurdjieff.

Suprematism was an important art movement in the world of non-objective painting, it ushered in new ways of seeing art and influenced many artists along the way in the Modern era. It was not just Malevich who was considered a pioneer of non-objective, or otherwise, non-representational, art.

Artists like Wassily Kandinsky and Piet Mondrian were among the pioneers of discovering a world that went beyond the physical function and representation of art using pure formal elements of art.

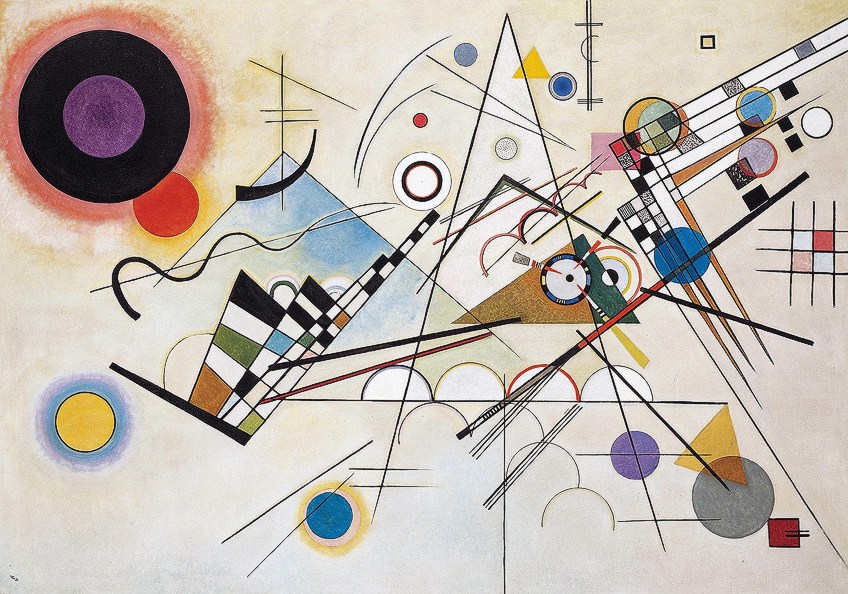

The Russian painter, Wassily Kandinsky, was a highly regarded Abstract artist of the 20th Century. He was among several other artists who started the art group called Der Blaue Reiter (“The Blue Rider”), which was part of the German Expressionist art movement. What made Kandinsky’s work revolutionary for its time were his abstract compositions.

He explored the deeper meanings of color in art and how it communicated more spiritually, in his seminal publication, Concerning the Spiritual in Art (1912), he explored these concepts in more detail, including comparing the use of color to music, but more broadly, the connection of art to music.

In his text, he explains how easily music expresses the inner world and how painters must “envy” this ease of expression.

Kandinsky started a series of abstracts that conveyed this deeper spirituality, these were called his Improvisations, Compositions, and Impressions. An example of this is his Composition VII (1913), which depicts an amalgamation of shapes and colors to the point where we, the viewer, cannot recognize anything figurative or representational.

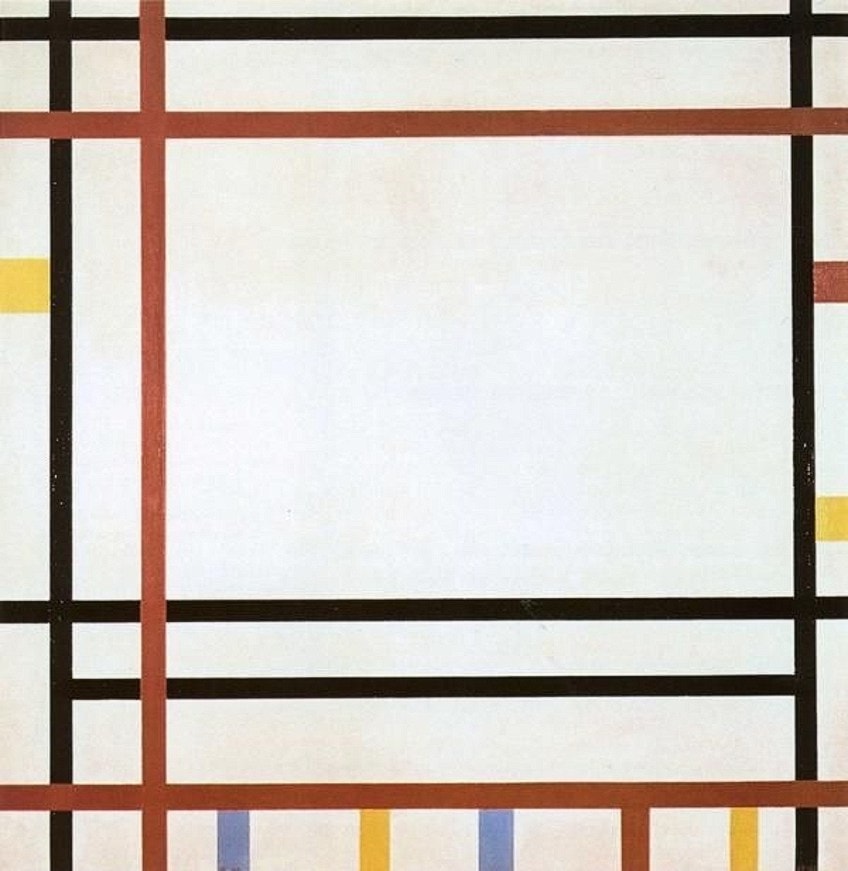

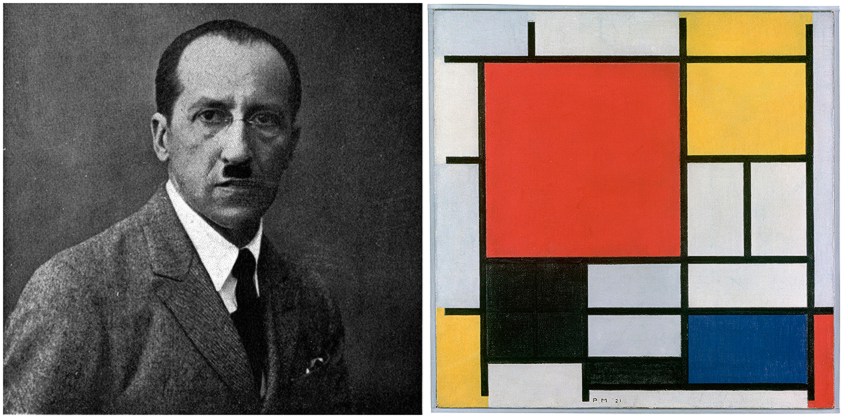

Another notable figure to mention in line with Non-Objective art is the Dutch Piet Mondrian. He was another leading pioneer in Abstract art during the 1920s. Relying on formal elements of lines and shapes he created non-objective paintings devoid of all recognizable representation. This simplicity of form also conveyed a deeper message of underlying universal values.

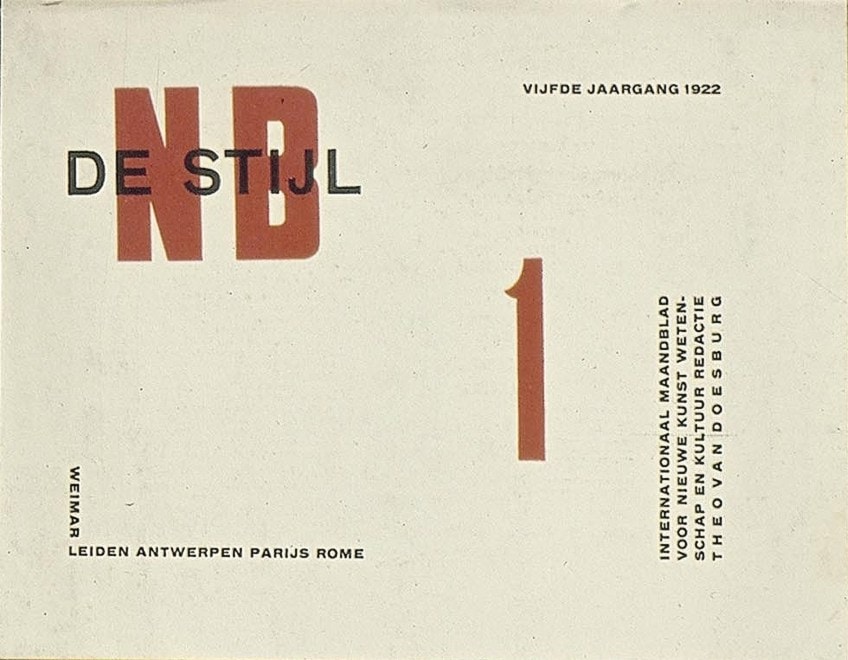

Mondrian also co-founded the De Stijl (“The Style”) art movement with Dutch artist Theo van Doesburg. Within this movement, Mondrian founded Neo-Plasticism, in 1917, which sought to go back to basics in art, so to say. This included depicting art in pure fundamental formal elements of color and lines, as mentioned above.

However, these were strictly horizontal and vertical lines along with right angles, and the only colors used were primary colors, namely, red, blue, and yellow and neutral colors like white, gray, and black.

Michel Seuphor, in his publication, Piet Mondrian: Life and Work (1956), provided a quote by Mondrian who explains art’s relationship with reality, he says, “Art is higher than reality and has no direct relation to reality”. He further states that artists will need to use reality to the minimal extent because reality is opposed to the spiritual”.

Neo-Plasticism was a radical art style and it aimed to depict an underlying harmony through art, this harmony was communicated in the most fundamental of shapes. Mondrian also wrote the essay titled, Neo-Plasticism in Pictorial Art (1917 to 1918), published in the De Stijl journal (also referred to as the De Stijl magazine by some sources).

In his seminal essay he explained what Neo-Plasticism aimed to achieve, stating: “As a pure representation of the human mind, art will express itself in an aesthetically purified, that is to say, abstract form. The new plastic idea cannot, therefore, take the form of a natural or concrete representation”. Furthermore, art will become about the “abstraction of form and colour”.

Van Doesburg eventually broke away from Neo-Plasticism and started the style called Elementarism. This went against Mondrian’s theories of strictly vertical and horizontal lines and included diagonal lines and tilted canvases. It was more dynamic than the more purist-driven ideals underpinning Neo-Plasticism. Some of the other Non-Objective art movements included the famous Cubism and Futurism, during the early 1900s, which were, in fact, large influencing movements on many 20th-century artists.

Orphism, also referred to as Orphic Cubism, started in 1912. This was an important art style that introduced the non-objective into the art world.

It was started as a response to Analytical Cubism by Sonia and Robert Delaunay and František Kupka. The movement focused on including brighter colors and forms into abstracted compositions that appealed to the senses; artists drew inspiration for the use of bright colors from the Fauvist art movement. The name “Orphism” was given by the Frenchman Guillaume Apollinaire, who was an art critic and writer.

If we look at the work from the earlier Analytical Cubism, which was around 1910 to 1912, and led by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, subject matter like portraits or still lifes became highly fractured into semi-abstract compositions.

The picture planes became multi-faceted and subject matter viewed from multiple perspectives all on one canvas. It was an art style focused on deconstructing the picture plane and overlapping the resulting fragments. This importantly became so abstracted that it became almost completely non-objective art.

There was not a large emphasis on bright colors in Analytical Cubism, artists utilized subdued or monochromatic palettes like browns, grays, ochres, blacks, and whites. The structural composition was the focal point of the paintings and there was no need to convey an emotion or symbolic meaning. Orphism, therefore, approached art differently and relied on color and overlapping picture planes as we see from Cubism.

Other Non-Objective art movements towards the later 1900s include Hard-Edge Painting, which started during 1959 when the art critic Jules Langsner organized an art exhibition, the Four Abstract Classicists (1959), displaying the geometric abstract work of four artists from California at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

The artworks appeared like that of Piet Mondrian’s grids and squares with the deeper colors that we see from the Color Field Painting style, which was a substyle of Abstract Expressionism. Well-known artists from the Color Field Painting style were Mark Rothko and Barnett Newman. What characterized the above-mentioned Californian artists was their impersonal approach to depicting form and color.

Frank Stella was another notable Hard-Edge painter and created compositions that focused on the formal elements of art, like color, line, and form.

He became known for his impersonal paintings, specifically his Black Paintings series (1958 to 1960). What made Stella different from artists like Piet Mondrian, for example, was that he did not have an intention to convey a deeper spiritual message through geometric abstraction. One of Stella’s famous quotes is, “What you see is what you see”.

There was also no inherent deeper meaning as we may see from the gestural Action painting style, in the work of artists like Jackson Pollock, for example. Additionally, Hard-Edge Painting artists created clean and neatly structured compositions with almost no hint of brushstrokes, and their shapes appeared hard with “sharp” edges. They were also influenced by the concept of unitary compositions.

Post-Painterly Abstraction started during the 1950s, it was used by the art critic and historian, Clement Greenberg, to name and curate an exhibition for various artists like Helen Frankenthaler and Morris Louis, all from different Abstract painting styles, including Hard-Edge Painting, Color Field Painting, Color Stain Painting, Lyrical Abstraction, Washington Color Painters, Minimal Painting, and others.

It was a response and rejection of the previous Abstract Expressionism (also called Painterly Abstraction) movement that Greenberg believed was too emotional and gestural. What characterized the Post-Painterly Abstraction style was the veer towards formal elements in art-making, for example, linear designs, color, and shape.

Non-Objective Art Examples

It is important to note that one of the primary underpinning characteristics of Non-Objective painting is the utilization of the formal elements of art. Formal elements of visual arts include lines, shapes, forms, colors, textures, space, value (contrast or luminosity). All these elements are combined to create the subject matter.

Below, we look at various Non-Objective painting examples from various artists across multiple art movements and styles.

It will clearly show the variety with which each artist has painted, specifically driven by their own inner intentions and desires to create art. Let us start at the earliest, the pioneer of Abstract art, Wassily Kandinsky.

Expressionism: Wassily Kandinsky (1866 – 1944)

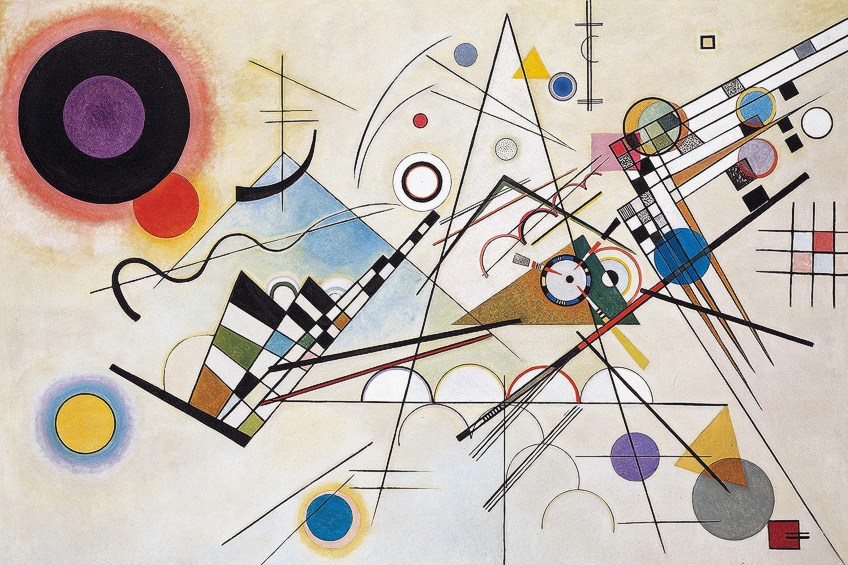

Wassily Kandinsky’s Composition VII (1913) is a fine example of a non-objective painting. In it we see a colorful mixture of shapes and lines all on one spatial area making up the canvas. With Kandinsky’s keen interest in music, we see how his canvas becomes almost like a composed piece, the title also reminding us of this connection to music.

Kandinsky clearly orchestrated his colors and forms in this painting and our visual sense perceives in much the same way as our auditory sense would a composed song.

This is an example of how Kandinsky utilized the style of non-objective art and attached a deeper symbolic meaning to it too. For example, he includes themes of the apocalypse and redemption by motifs like mountains, boats, and figures, but these are scarcely recognizable. The artists depicted these with reference to Biblical narratives like the Garden of Eden and the Last Judgement.

Other paintings by Kandinsky include Composition VIII (1923), which depicts how he incorporated aspects of Suprematism, Constructivism, and the Bauhaus School where he taught. This painting depicts Kandinsky’s exploration of lines and shapes, something wholly different from his previous painting mentioned above. Here it is an emphasis on form and not so much color. Later paintings by Kandinsky include Several Circles (1926) and Composition X (1939).

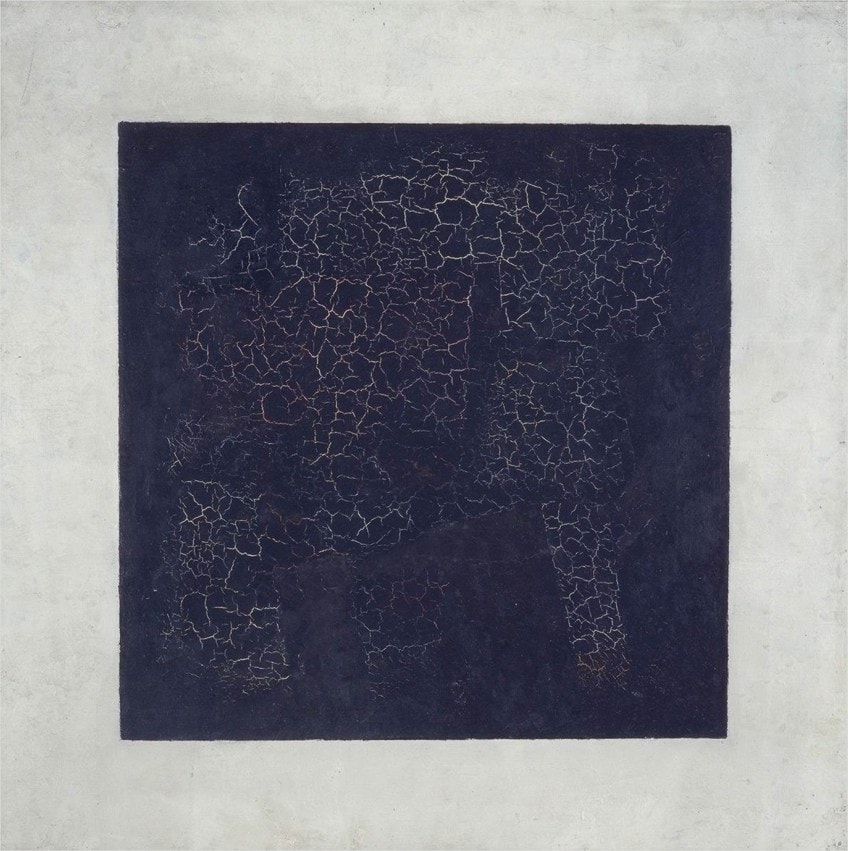

Suprematism: Kazimir Malevich (1879 – 1935)

Kazimir Malevich’s Black Square (c. 1915) simply depicts a black square on a white background. Presently the painting is cracked due to aging, however, there are other marks evident on this painting, for example, brushstrokes and fingerprints. This painting has been likened to an icon of sorts of non-representational art, emphasizing its spiritual qualities.

There are various other ways we can look at this painting apart from it being an “iconic” symbol. It is versatile to the viewer’s perspective. The simplicity of the shape and no other accompanying shapes or colors also creates a focal point for us, the black square, with no other distractions.

A fun fact about this painting is that it was initially part of Malevich’s sketch, in 1913, for a stage curtain for the opera called “Victory Over the Sun” (1926).

Other artworks by Malevich include Airplane Flying (1915), White on White (1917 to 1918), Painterly Realism of a Boy with a Knapsack. Color Masses in the Fourth Dimension (1915), and Painterly Realism of a Peasant Woman in Two Dimensions (Red Square) (1915).

Neo-Plasticism: Piet Mondrian (1872 – 1944)

Piet Mondrian’s compositions from the Neo-Plasticism style are examples that visually emulate non-objective art. If we look at his painting called Composition with Large Red Plane, Yellow, Black, Gray, and Blue (1921) we see the fundamental square and rectangular shapes with thick black outlines. The colors are limited to red, yellow, blue, and white with areas of gray. It is a simple rendering of formal elements of vertical and horizontal lines, which ultimately make squares and rectangles.

Furthermore, the blocks are asymmetrical, we see the large red square in the center and surrounding smaller blocks.

We will see this style varied in numerous other paintings by Mondrian, some will have different-sized squares and others will emphasize more thick black outlines. Examples include Composition with Color Planes (1917), Tableau I: Lozenge with Four Lines and Gray (1926), Composition II in Red, Blue, and Yellow (1930), Composition No. 10 (1939 to 1942), and Broadway Boogie-Woogie (1942 to 1943).

Orphism: Sonia Delaunay (1885 – 1979)

Sonia Delaunay was also involved in fashion, textile, and set design and she eventually incorporated a lot of her work into functional forms like furniture, wall coverings, and clothing. Along with her husband, Robert Delaunay, the couple co-founded the Orphism art style. Orphism was characterized by deep colors and shapes, and we see this exemplified in Delaunay’s various paintings.

Some examples include Prismes électriques (Electric Prisms) (1914), which depict various circular and arched shapes. The central area of the canvas has two larger circles and surrounding these are arcs, curves, and more geometric shapes like rectangles. The entire picture plane is multicolored.

The inspiration behind Delaunay’s electric prisms were the electric streetlights of the streets of Paris.

While Sonia endeavored to reproduce the glow created by streetlights, her husband, Robert Delaunay, endeavored to similarly reproduce the effects of the Sun and Moonlight in his work Simultaneous Contrasts: Sun and Moon (1912).

Hard-Edge Painting: Frank Stella (1936 to Present)

Frank Stella is a multi-talented artist, he is a sculptor, printmaker, and painter. His artwork has delved in and out of many art styles, most notably that of Minimalism. We will see many of his artworks appear non-objective, not representing anything but what is there, an example of this is from his Black Paintings series (1958 to 1960), The Marriage of Reason and Squalor, II (1959). Here we see a black canvas with nothing else but lines geometrically aligned with one another; these have been described as “inverted parallel U-shapes”.

Furthermore, there is no extensive indication of brushstrokes, and the work comes across as devoid of any figuration or reference to any other meaning or symbols.

What we see really is what we see here. The painting has also been explained as not trying to create an “illusionistic” three-dimensional space that we have all come to understand from paintings, especially if we use the Renaissance as an example, the opposite of what non-objective art is.

Stella’s Harran II (1967) from his Protractor (the late 1960s) series is another example but in this case, it is not monochrome, but multi-colored. Three circular shapes catch our attention; however, the entire composition is slanted diagonally and the circular shapes are almost housed within superimposed rectangular shapes.

This piece measures 10 x 20 feet and its large scale emphasizes the effect of the geometric and colorful shapes when standing in front of it, additionally, the flat two-dimensionality of the canvas becomes unavoidable. It is made from polymer and fluorescent polymer paint.

A Matter of Formality

The subject matter for Non-Objective painting has been utilized by many artists for many different purposes throughout the 20th and 21st Centuries. For some artists, it has been to convey a deeper, spiritual meaning. For some, it has been to create dynamism and rhythm. For others, it has been to echo the flow of music and the meaning of combined colors to elicit an emotional response. For some others, it has simply been to convey a shape and color, a design and structure, nothing more.

The subject matter of most Non-Objective paintings has been a matter of mere formality, an assortment of lines, shapes, and colors, but whatever purpose these assortments have served, it has not been in vain because Non-Objective art continues to create new dimensions, not only in our minds, but also our environments, and sometimes, something does not have to mean anything.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is Non-Objective Art?

Non-Objective art can be viewed from multiple perspectives. Some sources suggest it is a form or style within the category of Abstract art, others suggest it is not synonymous with Abstract art, and others suggest it is Abstract art. Non-Objective art is also called geometric abstraction. According to the definition provided by Tate, it is defined as “a type of abstract art that is usually, but not always, geometric and aims to convey a sense of simplicity and purity”.

What Is the Difference Between Non-Objective Art and Abstract Art?

Non-Objective art vs Abstract art is better understood when we look at how Abstract art is defined, namely, as art “that does not attempt to represent an accurate depiction of a visual reality but instead uses shapes, colors, forms, and gestural marks to achieve its effect”. Non-Objective art is a form of Abstract art where there are no representational qualities or likenesses to reality, it is completely non-representational and that is why it is also referred to as geometric abstraction.

What Are Non-Objective Art Movements?

Non-Objective art fits under various Abstract art movements, therefore, it is not an art movement per se, but more like a type or style of Abstract art. Non-Objective art can be found in art movements like Expressionism, Suprematism, Constructivism, Cubism, Orphism, Rayonism, Hard-Edge Painting, Post-Painterly Abstraction, and others.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Non-Objective Art – Finding a Non-Objective Art Definition.” Art in Context. December 3, 2021. URL: https://artincontext.org/non-objective-art/

Meyer, I. (2021, 3 December). Non-Objective Art – Finding a Non-Objective Art Definition. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/non-objective-art/

Meyer, Isabella. “Non-Objective Art – Finding a Non-Objective Art Definition.” Art in Context, December 3, 2021. https://artincontext.org/non-objective-art/.

I propose that abstract art began millions of years ago. Look at images of the telescopes in space…what are they if not abstract art? Look at the clouds above us. Abstract art. The cracks on the sidewalk…etc

Alfredo Santesteban