Color Field Painting – The History of Color Block Art

Non-objective painting was born long before the Abstract Expressionist movement, but the Color Field school of painting emerged in the 1950s and has since found followers from around the world. Some artists of the genre pursue simplified compositions, focused purely on the impression of color. Other Color Field painters use process and color psychology to evoke emotion.

The Canon and Culture of Color Field Painting

In Cubist or Impressionist work, dabs and fields of color represented real things. These works were an abstraction of objective reality. In Color Field painting, areas of blue or green do not have to stand for sky or grass. These colors represent themselves and perhaps their relationship to each other or the surface.

In this way, the painterly object began to blur the line between painting and sculpture.

What is Color Field Painting?

The Color Field Painting definition could be characterized as a niche of Abstract Expressionism. Post-Painterly Abstraction or Chromatic Abstraction are other stand-ins for the Color Field painting definition. Color Field painters working in the 1950s and 1960s removed figuration and subject matter until their work was characterized only by large areas of flat color.

Like Abstract Expressionism, Color Field painting rejected narrative. Unlike the Abstract Expressionists though, the artists associated with the Color Field movement also rejected gesture, brushstroke, and expressive action in favor of form and color.

Color Field painters used subtlety and calmness to explore variations in monochromatic hues, and the transitions from one tone to another. For Color Field painters, color was the subject. With discreet tonal values and large unbroken fields of color, many of these paintings depended on elements of nature such as gravity and time, rather than the artist’s hand.

Color field painters made use of simple geometric shapes, stripes, patterns, through large fields of color that were spread onto a surface.

The pure, abstract form was often achieved through laying, pouring, staining, or dropping paint across the typically large canvasses. For Color Field painters, all that mattered were the physical attributes of a painting.

The Origins of Color Field Painting

The color field movement sprang out of experiments in nonrepresentational painting and while it evolved in the mid-century, a politically and socially tumultuous period of American history, this aesthetic is distinctly apolitical. It is not about the exterior world but rather the interior world of the painting, the artist, and the viewer.

European Abstraction

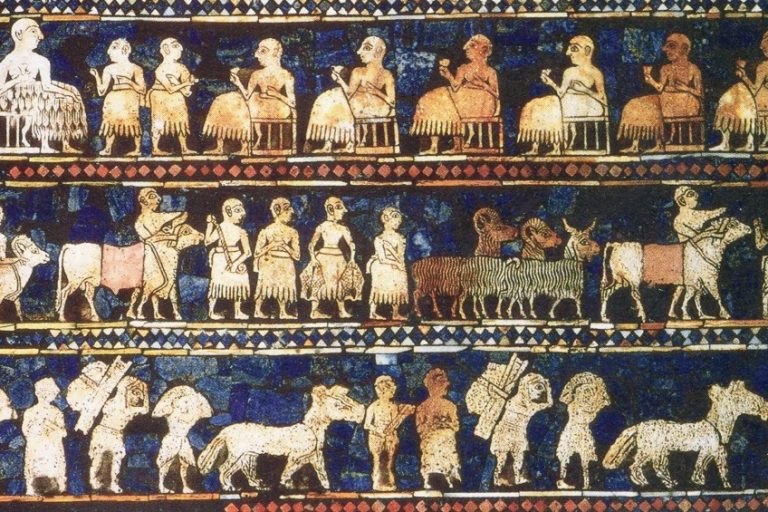

Before World War I and within the 1917 Russian Revolution, painters like Kazimir Malevich had already made a splash with the non-figurative style of color block art. Preferring the term Suprematism, Malevich had never used the term “abstraction” to describe his work.

Regardless, Malevich’s color block paintings deliberately presented “a new painterly means”.

World War I was followed by a fleeting dalliance with Dadaism and then Surrealism, which was fundamentally about meaning and uncovering the subconscious through biomorphic, psychic automatism. While Surrealists like Max Ernst and Andre Breton rejected reality, they still figuratively represented fantasy or dreamscapes.

Artists like Yves Klein resurrected the color block art style of the early 20th century. Such artists sought pure Abstraction for what it was and nothing else.

This formal, non-objective, and reduced form of Abstraction was the new aesthetic and rendered figuration as outdated. However, as the Nazis took control of Germany, modernist artists were persecuted as degenerate, and schools like Bauhaus were shut down because they were seen as conduits for ethnic mixing.

American Abstraction

During World War II many European artists, poets, and scholars became refugees and took exile in New York City. By the end of the war, modernism had become an American phenomenon. The seeds of Surrealism and European Abstraction had coalesced in New York to produce a new movement called Abstract Expressionism.

Because many American ensemble musicians had been drafted into the war at the start of World War II, musicians began experimenting with a new type of jazz called bebop. This improvisational style hugely influenced Abstract Expressionists, who emphasized action, gesture, brush strokes, and mark-making in their works.

They saw painting as a transcendental act that requires free, expressive action. In this essential part of their work, they threw their paint, dripped, or attacked their canvas. The famous Irascibles were at the center of the New York School art. They included Willem De Kooning, Jackson Pollock, Robert Motherwell, Barnett Newman, Willem De Kooning, Ad Reinhart, Arshile Gorky, Josef Albers, Hans Hoffman, and Piet Mondrian.

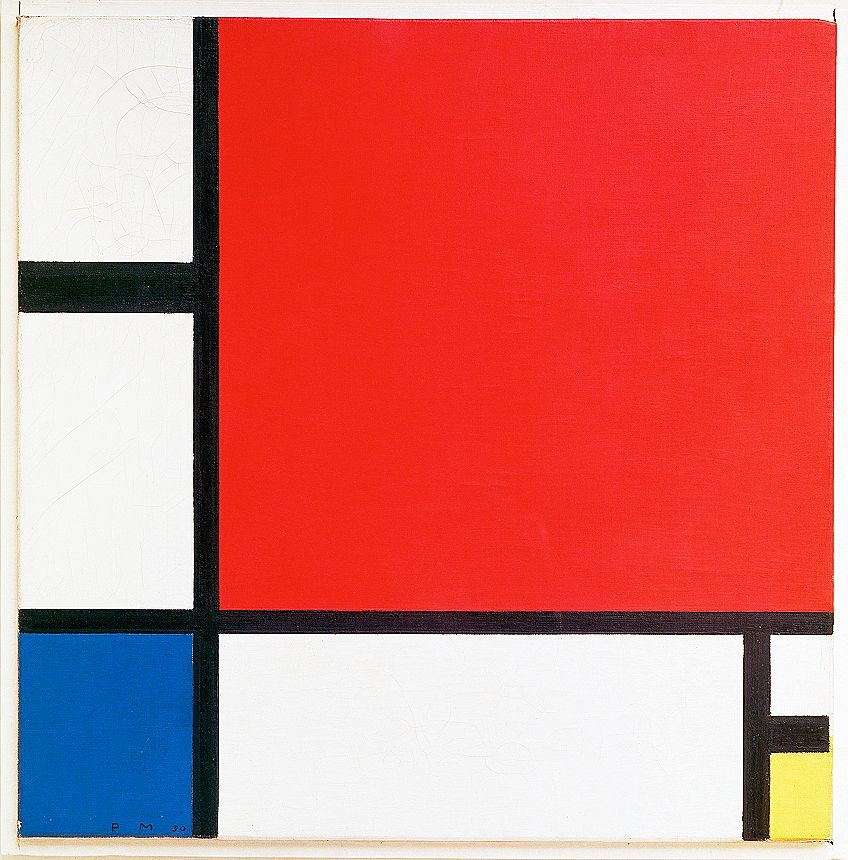

Piet Mondrian was well known for his forays into abstraction with very formalized, planned, logical compositions like “Composition No. 2 in Red Blue and Yellow” (1930), which consisted of color block painting.

In lower Manhattan, Soho, and Greenwich Village these artists formed a wholistic, progressive view of art in line with the times. The group of friends gathered at a low-class haunt called The Cedar Tavern on University Place in Greenwich Village where the drinks were cheap and they spend time talking about art.

On the periphery of this clique were other artists like Robert Rauschenberg, Franz Kline, Barnett Newman, Helen Frankenthaler, and Mark Rothko, as well as critics Harold Rosenberg, Clement Greenberg, and Meyer Shapiro.

These were essentially immigrant artists drawing from European Abstract painters who had made the initial geometric abstractions. This new generation picked up on the spontaneity and expressive nature of the Surrealists. They fused the two movements and came up with Abstract Expressionism. It was abstract because it did not represent anything, but it tried to evoke feeling and emotion.

Critical Transitions

These artists demonstrated different styles but the concepts behind them had something in common. The theory behind Abstract Expressionism became central because it often preceded the technique. This was the first truly collaborative relationship between theorists and artists which laid solid foundations for a movement with influence and longevity.

The fusion between theory and practice was unique because, until that point, theorists had almost always been trailing behind the experiments of the Avant-Garde.

Either that or artists themselves had played the role of the theorist such as the Futurists for example who wrote their own manifesto. Theory and practice had either been borne together co-incidentally or one had been the by-product of the other.

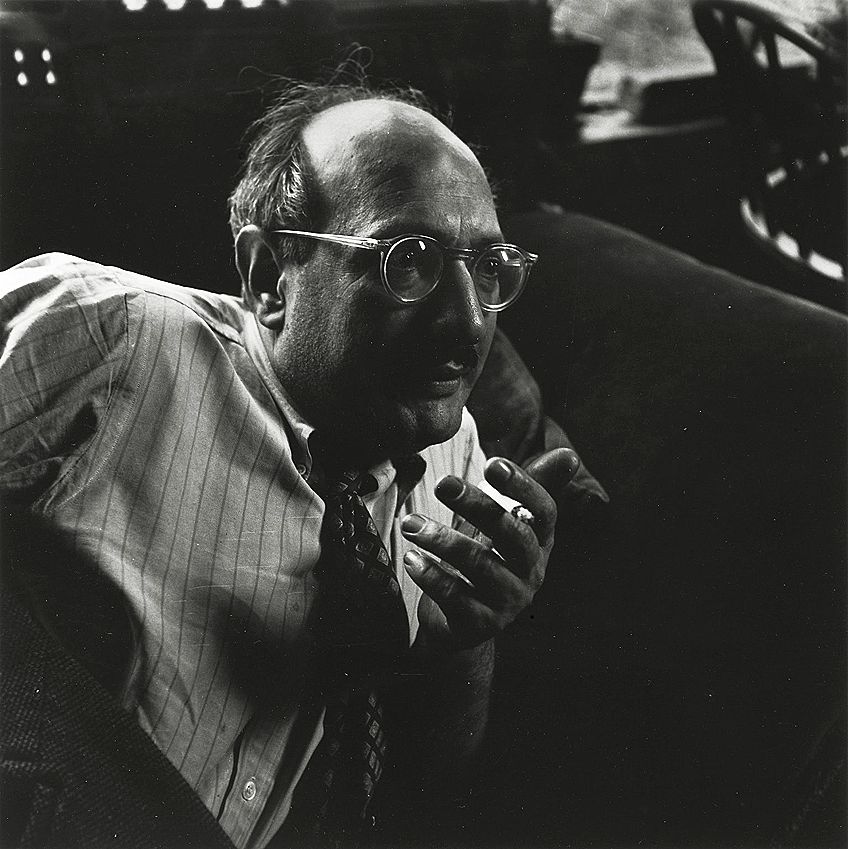

Based on the improvisational form of beatnik poetry and bebop jazz, Harold Rosenberg, who coined the term “action painting”, was a devout defender of Abstract Expressionism. Rosenberg championed Pop Art and Performance, and artists such as Andy Warhol and Robert Rauschenberg. Art critic and theorist Clement Greenberg saw this kind of work as kitsch, deeming it a low form of art and pure art as high art.

This debate became so central that curators and artists began presenting what they thought would succeed in Abstract Expressionism.

Clement Greenberg (1909 – 1994)

Greenberg articulated a new movement of painting derived from the Abstract Expressionism of the 1940s and 1950s. This new art form favored openness and clarity as opposed to the fussy surfaces of Expressionism. Towards the end of the 1950s more artists had moved in this direction and the transition from Abstract Expressionism to the Color School bolstered Greenberg’s theory.

By the 1960s, artists were moving away from gesture and angst completely in favor of clear surfaces and gestalt.

Clement Greenberg had lost faith in the second-generation New York School artists and found Abstract Expressionists derivative, parting from his once favored artist Jackson Pollock to instead promote Color Field painters such as Clyfford Still who presented a more refined, conceptual form of Abstraction. Greenberg saw this as a necessary response to Conceptualists and Pop Artists, who claimed that it was the concept of the art that mattered and not the execution.

Formalism became the concept of these new paintings, which reduced everything to the flat surface and removed the artist’s hand. These artists sought the inherent and self-defining properties of the medium itself. Rebuking subject matter, they focused on an essence of painting that did not depend on a narrative. Because these characteristics resembled Color Field painting movements of previous eras, like Malevich’s Suprematism, Greenberg’s movement can be called second-generation Color Field painting.

Clement Greenberg became the champion of this movement and believed it was the triumph of American modernism. He contributed to how people made and experienced these paintings by rallying around artists who were associated with his notion of the bare element of painting (which was pure form). Greenberg called his movement Post-Painterly Abstraction.

Post-Painterly Abstraction

Clement Greenberg curated an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in Los Angeles County which he titled Post-Painterly Abstraction. The exhibition was opened from the 23rd of April until the 7th of June 1964 and subsequently toured to the Walker Arts Centre in Minneapolis and the Art Gallery of Toronto. It was a landmark exhibition in American art history.

To appraise Post-Painterly Abstraction, Clement Greenberg chose the term Modernism instead of Avant-Garde.

In his essay for this exhibition Modernist Painting, Greenberg made a case for the 31 American and Canadian artists he had selected which included Jack Bush, Paul Feeley, Ray Parker, Sam Francis, Helen Frankenfeller, Lonnie Lanfield, Hans Hoffman, Elsworth Kelly, Morris Lewis, Kenneth Noland, Clyfford Still, Frank Stella, and Gene Davis. Greenberg particularly favored Washington DC field line painter Kenneth Nolan.

Greenberg lingered on another Washington DC Color Field painter, Morris Louis. Louis spilled veils of thin paint onto his unsized, unprimed cotton duck canvas. Rather than merely covering it, Louis soaked the fabric in paint. The pigment and fabric were fused into a single layer. This technique of stain painting identified by Greenberg in Louis’ work was the perfect way to articulate his concepts around how the painting had become materially integral to itself.

Greenberg positioned Post-Painterly Abstraction as a logical progression from Abstract Expressionism. The term covered the range of Color Field painting techniques of the late 1950s and early 1960s.

In a moment when American consumerism and technological advancement were at a fever pitch, the movement was characterized by its materialistic approach. Post-Painterly Abstraction was not about representation or feeling, but about the properties of color, the texture of the surface, and the shape of the frame.

Three Key Color Field Painters

Once they were no longer bound by the paintbrush or the easel, Color Field painting techniques were innovated and diversified. After the 1960s, Post-Painterly Abstraction was succeeded by its descendants of Minimalism, Hard-Edge painting, and Neo-Abstraction. However, Color Field painting never died.

Some of the most successful Color Field painters such as Helen Frankenthaler, Barnett Newman, and Mark Rothko are renowned and inspired many future generations.

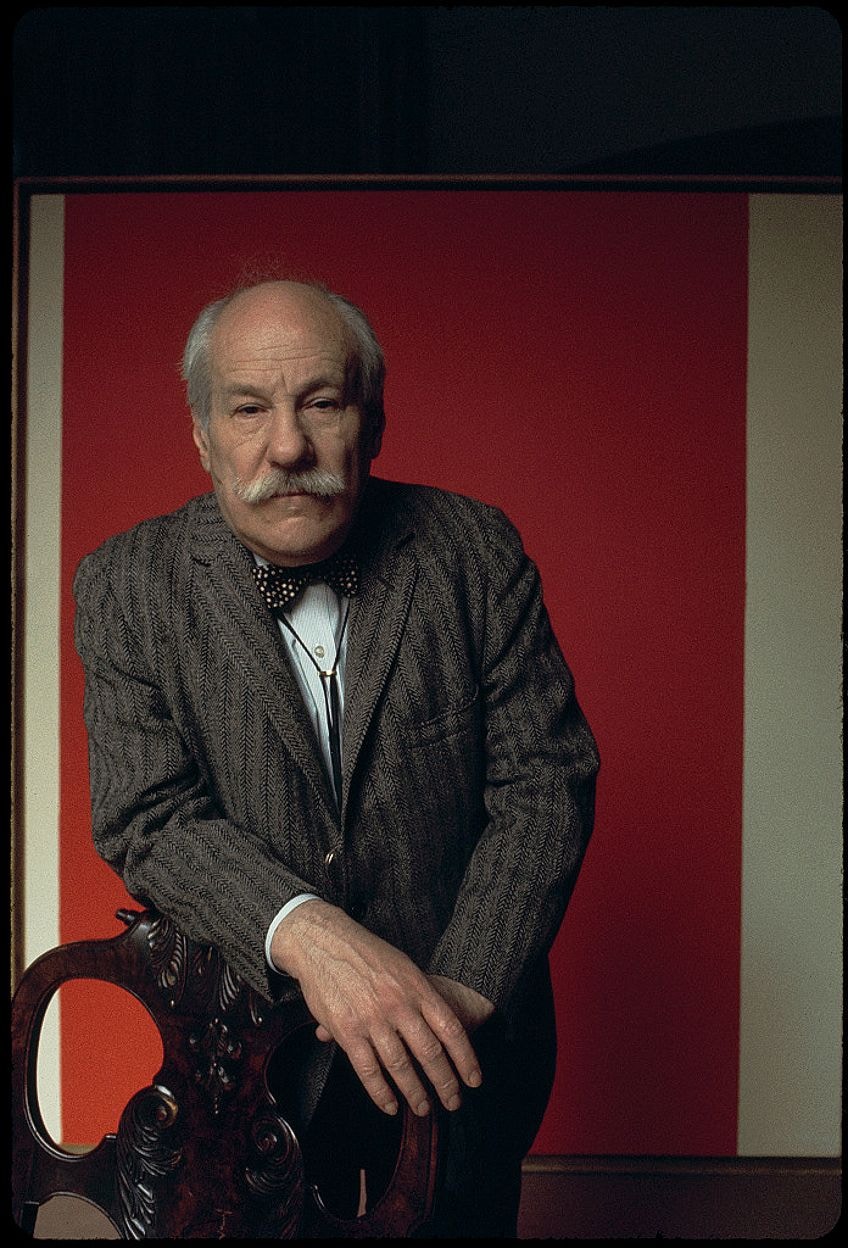

Mark Rothko (1903 – 1970)

| Birth Date | 25 September 1903 |

| Death Date | 25 February 1970 |

| Places Lived | New York |

| Associated Art Movements | Color Field painting |

Around 1949, Mark Rothko saw Henri Matisse’s Red Studio (1911) at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. The work made such an impression on Rothko that he would revisit it often. What struck him was Matisse’s use of color. This, combined with his associations with numerous Abstract Expressionists artists such as Barnett Newman, Robert Motherwell, and Jackson Pollock, helped shape his career.

Over the years, Rothko experimented with several artistic styles before accessing a new visual language that had an abstract, formless quality. The signature style consisted of subtle rectangular shapes which seemed to hover on further fields of color.

This motif which can be seen in works like Red on Maroon (1959) does have a gestural quality to it, but unlike the works of Pollock or De Kooning it is softened down, yet somehow more iconic. Rothko’s earlier Color Field paintings are characterized by lighter hues. His huge canvases often featured analogous or monochromatic tones as he was interested in the relative properties of color. The geometric shapes which formed the subtle, soft tones were rough around the edges creating a sense of depth and movement. Rothko’s tones got progressively darker over time.

Rothko’s technique involved painting onto unprimed canvas and experimenting with opacity by thinning, thickening, and layering paint. From 1957 onwards, he began priming his canvases with deep maroon paint and skim glue which tightened the canvas. With rapid strokes, Rothko achieved the feathered fields using large five-inch house painters brushes. Turpentine was used to thin the paint and to wash, stain, layer, and scrub away hard edges.

Because Rothko rotated paintings during his process, visible paint drips run sideways and upwards on his surfaces.

Inspired by Friedrich Nietzsche’s notion that art should dramatize the horror of existence, Mark Rothko used his Color Field painting technique to explore the emotional properties of color. As far as he was concerned, a Color Field painting was an experience. His works were designed to be seen as contemplative and up close. They were large and hung low so that the viewer could feel engulfed.

The subliminal and soothing encounters eventually made Mark Rothko the most famous Color Field painter of all time.

Barnett Newman (1905 – 1970)

| Birth Date | 29 January 1905 |

| Death Date | 4 July 1970 |

| Places Lived | New York |

| Associated Art Movements | Color Field painting |

Barnett Newman is one of the primary painters to anticipate and experiment with Color Field painting techniques. Newman’s main source of expression was his famous zips which are individual vertical lines of color on the surface of his paintings. The zips were constructed with tape that’s been placed, painted over, then removed. Some zips are much more subtle than others giving the illusion of large fields of color, voids, or a sense of depth and movement.

Newman saw the artist as a visionary on a heroic mission for universal truths, which he sought to impart to the viewer through his Color Field paintings. He believed that we all had a sense of the sublime and he wanted to get us there. He wanted his enormous paintings to be seen from 18 inches away so they could access the subconscious on an intimate level.

His painting Cathedra (1951) is meant to inspire contemplative stillness. Because it appears as flat areas of color, it can be deceptive. Closer observation reveals layers upon layers of paint, giving the painting a subtly vibrational quality. Newman was not afraid of subject matter. He was Jewish and inspired by religious themes. His series Stations of the Cross (1958-1966) referred to the passion of the Christ and encouraged spiritual contemplation.

Vir Heroicus Sublimis (1950-1951) shows an unmodulated color field which for Newman represented infinity. The large monochromatic work is not meant to be understood. While Vir Heroicus Sublimis does inspire curiosity and a desire for meaning, Newman was merely offering a transcendent moment and connecting the viewer to spiritual stillness in a hectic world.

His first exhibition in 1951 turned out to be such a failure that he stopped painting for seven years until a reappraisal of his work occurred at the end of the 1950s.

Clement Greenberg was among the first to defend Newman’s work awkwardly attributing to it a quality of Primitivism and comparing it to Prehistoric Art. Greenberg proposed that Newman was faithful to the metaphysical or spiritual Abstract Expressionist inclinations like Jackson Pollock except, unlike Pollock, Barnett Newman’s attempts were more conceptual than physical.

While Jackson Pollock enjoyed great commercial success and fame, he lacked imitators. The drip technique was one dimensional and dead-ended, but the simplicity of Barnett Newman’s zips would inspire Color Field line painters and shape Minimalist art.

Helen Frankenthaler (1928 – 2011)

| Birth Date | 12 December 1928 |

| Death Date | 27 December 2011 |

| Places Lived | New York |

| Associated Art Movements | Color Field painting |

In her tactile and physical process, Helen Frankenthaler laid her canvases on the floor of her East 83rd Street New York studio. Without stretching or priming it, she would pour watered-down paint from a bucket onto the canvas. Letting it soak and spread naturally Frankenthaler then used squeegees, sponges, mops, tape, paintbrushes, and her fingers to distribute the paint across the surface creating stained fields of color. Her technique allowed the paint to seep or fade out through the canvas, or merge and emerge as thicker paint.

Frankenthaler’s drawing was organic and transparent, but her soft edges, monochromes, and empty areas of canvas amongst the fields of color showed consideration and control.

Some paintings took a week to complete while others took much longer. The orientation of a painting would sometimes reveal itself once she had brought the painting to its conclusion. She surrendered to the process and embraced mistakes. Her method of painting and suggestive titles gave Frankenthaler’s paintings their character.

Hybrid Vigor (1973) is an explosion of swaths color into which the artist injected thin lines of tenderly applied brushstrokes. The line between chaos and control elevates Hybrid Vigor where the fields of lime green and yellow, and the thin blue line at the base of the blue field, connects the two green peninsulas creating a work that is calm yet dynamic.

Helen Frankenthaler’s The Bay (1963) is about six and a half feet square and is made with diluted acrylic paint poured onto the canvas. Frankenthaler’s soak-stain method produced variations of blue tones within an organic shape which reads as a body of water. It hovers over the flat green area that is diagonally divided giving the image a living quality and depth while the natural off-white background provides calm contrast. The asymmetrical composition was selected for the American Pavilion of the 1966 Venice Biennale.

As a second-generation Abstract Expressionist, Frankenthaler’s work has a distinct sensibility. Helen Frankenthaler did not limit herself to Post-Painterly Abstraction and made abstraction generative for her own aims. Her notion was that colors, shapes, and lines are infinitely variable. Instead of using line to delineate or describe spaces, she found ways to depict space without depending on it, yet every mark she made was line. She inspired painters such as Kenneth Nolan and Morris Louis, who called Frankenthaler “a bridge to what was possible”.

A Field of Dreams

Greenbergian theories could not stand the test of time because pure painting is essentially impossible. In an increasingly globalized and modernized culture, everything, down to the canvas or paint used, where it came from, or the money used to get the materials constitutes subject matter.

Today’s audience is more discerning and critical of cultural construct. But even in today’s Postmodernist moment, color continues a beguiling subject for artists.

We are inundated with color technology and colorful things, yet a full and formal knowledge of color somehow remains intangible. The art world continues attempting to find ways of communicating the sublime properties of color which have captured its imagination, offering opportunities to occupy fantastic worlds.

The Color Fields exhibition at the Deutsche Guggenheim which was opened between the 22nd of October 2010 and the 10th of January 2011 compiled important examples of Color Field paintings from the 1960s. Every artwork except the Larry Poons from the Guggenheim Bilbao belonged to the Guggenheim collection of New York. The exhibition surveyed the vibrant movement both in Europe and America through artists like Ad Reinhart, Josef Albers, Morris Louis, and Kenneth Nolan.

Because Color Field painting was forthright about its means of production, it was particularly accessible. Through its wide variety of methods and its ambiguity Color Field painting can be a window into our subconscious. Once a viewer engages with a painting subliminally, the possibilities are endless. This is one of the reasons the Color Field painting has been recognized as one of the key achievements of Western art.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is Color Field Painting?

Color Field painting is an American abstract art movement popular from the 1940s to the 1960s which featured large areas of unmodulated color covering the majority of the canvas.

What Was the True Meaning of Color Field Painting?

Color Field painting is not about anything other than itself. It is only about the colors and shapes as they appear on the canvas. There is no right way to react to these works, but Yves Klein once suggested that we simply experience his work as we would experience a sunset or a sunrise.

What is the Color Field Painting Technique?

There is no universal Color Field painting technique. Artists invented their own methods, rules, and ideas, which took their work in different directions.

Was Color Field Painting Avante Garde?

Yes. In its infancy, Color Field painting did not fit the prescribed categories of the pre-World War modern world. It was experimental, and these artists were finding new ways to see the form.

What is the Difference Between Color Field Painting and Minimalism?

These fields are very similar. Like Color Field painters, Minimalist artists decided to distance themselves from Expressionism because it was too subjective and personal. But Minimalists went further in removing the artist’s influence. The term Minimalism made a much bigger impact in sculpture and can thus be seen as the sculptural form of Post-Painterly Abstraction.

Was Josef Albers the Godfather of Color Field Painting?

He has been called the father of the square, but Joseph Albers’ was certainly a key figure of Color Field painting. Albers who had been a teacher at Bauhaus had a long history with Modernism. He was a color theorist, well known for his Homage to the Square series (1949 – 1976) which adopted the new concepts of post-gestural painting.

Is There Any Footage of Morris Louis Painting?

No. Unlike many other artists of this period, there is no documentary imagery of Morris Louis at work. Our insights on his technique are anecdotal and largely speculative based on the canvases themselves. He let gravity compose his paintings which often ended up with no discernible touch or orientation, which Louis intended.

Is the Cedar Tavern Still Open?

Unfortunately, it is closed. After the Abstract Expressionists had brought it notoriety, it turned into a trendy scene for bohemian types. But this had also driven away The Cedar Tavern’s regular clientele and once the hype had passed, the place went bust and had to close its doors.

Heidi Sincuba was the Head of Painting at Rhodes University from 2017 to 2020 and part of the first Artist Run Practice and Theory course at Konstfack in Stockholm, 2021. They completed their BFA at Artez Arnhem in the Netherlands, MFA at Goldsmiths University of London, and are currently a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Cape Town.

Heidi Sincuba’s own practice explores fugitivity through painting, drawing, text, textiles, performance, and installation. This praxis is founded on a conceptual intersection of biomythographic experimentation, existential automatism, and African ancestral knowledge systems. These methodologies of multiplicity result in a fluid and speculative aesthetic, continually manifesting and metamorphosing its material conditions.

Learn more about the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Thembeka Heidi, Sincuba, “Color Field Painting – The History of Color Block Art.” Art in Context. March 16, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/color-field-painting/

Sincuba, T. (2022, 16 March). Color Field Painting – The History of Color Block Art. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/color-field-painting/

Sincuba, Thembeka Heidi. “Color Field Painting – The History of Color Block Art.” Art in Context, March 16, 2022. https://artincontext.org/color-field-painting/.