Analytical Cubism – Who Developed Analytical Cubism?

What is Analytical Cubism and who developed Analytical Cubism? These are the pertinent questions we will be addressing in this article. You have most likely heard of Cubism before, but do you know the difference between Analytical Cubism vs. Synthetic Cubism? Let’s take a look at its history and famous Cubist artists who used the style, such as Pablo Picasso, as well as Analytical Cubism examples.

What Is Analytical Cubism?

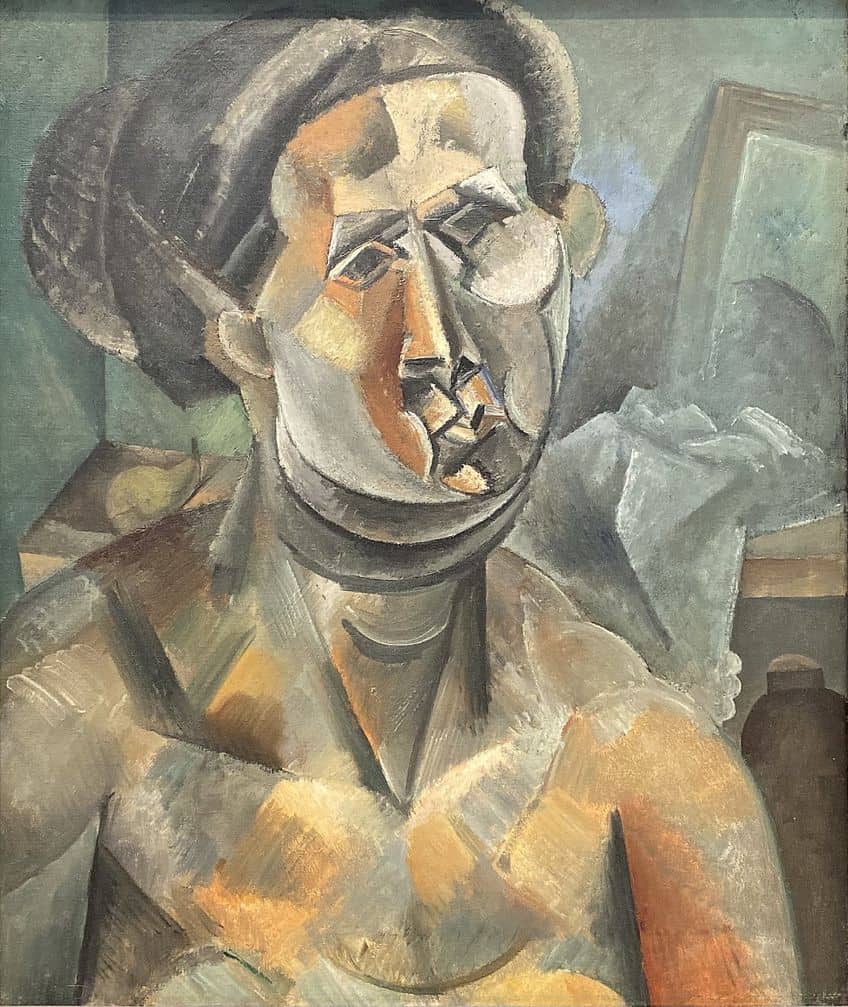

Analytic Cubism is a Cubist technique that splits the subject into angular, multi-layered surfaces, bringing still lifes and portraits close to complete abstraction. During a two-year phase of experimentation in which Cubist painters were inspired by Paul Cézanne’s faceted landscapes, Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque returned to the studio and perfected the technique of Analytic Cubism. The Analytic Cubism phase established a manner of thinking about art that extended beyond the boundaries of fixed perspective compositions by using various viewpoints to make images that contained only fleeting snippets of everyday objects as we know them.

Analytic Cubism increased the amount of cognitive participation in art. Analytic Cubism used a limited selection of hues and tones in order to separate itself from the enticing style of Impressionism and the Fauves. Excess color would have just acted as a diversion from a type of art that encouraged the viewer to analyze art instead of merely experiencing it.

The Emergence of Analytical Cubism

Before Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso appeared to have developed techniques of pictorial perspective on their own, Paul Cézanne was the dominant influence on the pursuit of artistic plasticity and form. Cézanne started to portray the environment using cones, spheres, and cylinders in the late 1800s, allowing the varied viewpoints of the picture plane to direct the viewer’s eye toward a focused focal point. Cézanne’s art demonstrated unequivocally that painting is not merely the art of mimicking an object with colors and lines, but of giving plastic (solid but malleable) shape to our nature. Georges Seurat’s art, known mostly for its vast color palette and flat depth of field, stimulated the emergence of Cubism, although indirectly. His paintings and sketches were extensively viewed in Paris as a result of multiple exhibits, and copies of his most renowned works were disseminated widely among the Cubist artists.

Analytic Cubism’s focus on composition and tone as separate aspects was compatible with viewing color as an autonomous formal element as Suerat had done.

The Characteristics of Analytical Cubism

Analytical Cubism artists made fragmentation and abstraction central to their creative style. The act of reducing things into geometric forms and planes is referred to as fragmentation. Objects were condensed to their essential geometric shapes in Analytical Cubism, such as spheres, cubes, and cones. Those forms were then disassembled into even smaller shapes and then reassembled in a way that highlighted the object’s fundamental structure. The practice of eliminating recognizable objects or structures from the artwork is referred to as abstraction. Artists in Analytical Cubism attempted to create compositions that were almost entirely abstract.

Objects were fragmented and reconstructed in ways that made identification challenging. Analytical Cubism’s primary focus on abstraction and fragmentation enabled artists to develop a new visual language that was both original and challenging. They were able to produce artworks that were both sophisticated and aesthetically appealing by breaking down objects into their fundamental shapes and recombining them in a fashion that highlighted the object’s structure and underlying geometry. Analytic cubism uses geometric forms to break down objects into their basic elements rather than depicting them as a cohesive whole.

This enabled painters to depict objects from numerous perspectives at the same time, producing a sense of motion and dimension within the image.

To give the illusion of depth and dimensions in their paintings, the artists would utilize a variety of subdued hues such as browns, grays, and ochres. Instead of distracting the spectator with bright, dramatic colors, this lets them concentrate on the structure and shape of the things they were depicting. The artists were also able to create a feeling of unity and harmony in their works due to the limited color palette since all of the hues were carefully picked to work together. This contributed to the creation of a coherent, unified image that was easy for the audience to interpret.

Important Analytical Cubists

To leave one foot firmly planted in the domains of reality, Analytic Cubism included what Picasso referred to as “attributes” into its framework of planes and geometric grids. Attributes were snippets or elements from ordinary life; sources of illusionistic reference that made the picture’s characteristics accessible, preventing the work from slipping into pure abstraction. Pablo Picasso was not the only person to contribute to Analytical Cubism, though. Let us now explore a few of the most significant artists of this genre.

Pablo Picasso was a key figure in the establishment of Analytical Cubism as an art style and he is recognized for co-founding Cubism. His participation in Analytical Cubism constituted a dramatic shift from the more traditional types of art that had come before it. Picasso started to experiment with novel ways of depicting objects on his canvases in the early 1900s. He was influenced by African art in addition to the works of Paul Cézanne, and he started to disassemble things and portray them from numerous viewpoints and in fragmented shapes. Picasso’s early analytical cubist paintings emphasized geometric outlines, flat forms, and a restricted color palette, such as Ma Jolie (1912). He frequently used subdued hues, such as brown and gray, to create the illusion of depth in his paintings. Picasso worked closely with Braque on the creation of Analytical Cubism, in addition to his own works.

The painters shared their ideas and techniques with each other, and their artworks from this time period are regularly hard to tell apart.

The French artist Georges Braque is acknowledged for co-founding Analytical Cubism with Pablo Picasso. Braque’s participation in this movement was critical to its growth and progress. Like Picasso, his early paintings in this style included fragmented shapes, subdued colors, and a flat sense of space. Braque’s artwork from the analytical cubist period typically included identifiable objects, like bottles or musical instruments, that were deconstructed and reassembled in flat, geometric shapes. This technique emphasized the object’s structural features while challenging established concepts of representation in art. Braque’s participation in Analytical Cubism set the groundwork for the emergence of other modern art movements, like synthetic cubism, in the years following World War I. Along with Picasso, his contribution to this movement served to significantly influence the path of contemporary art.

Juan Gris, the Spanish artist, was one of the important artists who kept working on the style after its co-founders had moved on to different directions. Before transitioning to painting, Gris worked as a caricaturist and illustrator. He soon became identified with the cubist style and was highly influenced by Picasso and Braque’s works. Gris’ approach to Analytical Cubism was characterized by an emphasis on object study and reassembly. One of Gris’ defining methods was collage, in which he would combine real-world items into his works, such as newspaper clippings or pieces of wallpaper. This gave a new depth to his work and pushed the boundaries of what could be represented in a picture. Gris’ art was distinguished by its precision of form and delicate use of color. He generally used a subdued palette, with beige, gray, and white dominating. Essentially, Gris’ contributions to Analytical Cubism contributed to the style’s development and refinement beyond its early stages.

The Development and Influence of Analytical Cubism

By 1912, Picasso and Braque had launched a new phase of Synthetic Cubism, in which they de-emphasized image fragmentation while using realistic materials such as rope or oilcloths in their artworks. Yet, at separate stages in their vocations, both artists would continue to create works inspired by Analytic Cubism concepts. While being considered somewhat subservient to Braque and Picasso, the so-called Salon Cubists were essential in spreading Cubism’s popularity beyond an exclusive class of art reviewers.

Prominent historical masters such as Gris and Delaunay used some of the methods of Analytic Cubism but added a more bright and vibrant use of color to their paintings.

Influence on Subsequent Styles

Their contributions intended to allow for a more dreamy quality to impact an art form that had become strictly analytical in the hands of Picasso and Braque. The Salon Cubists also progressed: Delaunay pioneered Orphism, stressing brilliant, fragmented shapes; Leger pioneered Tubism; while Gleizes, Metzinger, and others developed pure abstract paintings that stressed the flat visual plane. Analytic Cubism, for its part, established many of the foundational principles of 20th-century modernism with its fragmented forms and planes. It influenced the growth of Suprematism, Italian Futurism, Constructivism, and, subsequently, Purism and de Stijl, as well as Le Corbusier’s art and architecture.

The Decline of Cubism (1948) by Clement Greenberg emerged as a significant work in recognizing the historical significance of the Cubist movement as a whole. “Cubism is still the only essential style of our era”, he stated, “the only one most suited to represent a modern mood, and the only one worthy of upholding a tradition that will live into the future and develop new artists”. Cubism’s shattered, multi-dimensional aspect influenced other media, most notably the films of Jean Cocteau and Sergei M. Eisenstein and the writings of Blaise Cendars, Gertrude Stein, and William Faulkner, which hit its peak in the near-abstract Analytic phase.

Analytical Cubism was among the earliest art movements to abandon representation in favor of abstracting objects.

Abstract Expressionism and Minimalism were influenced by this approach to abstraction. Analytical Cubism artists used collage components in their works to produce texture and depth. This method encouraged the emergence of collage as a distinct art genre. The emphasis on geometric shapes and forms, such as cubes and spheres, in Analytical Cubism, had a profound effect on succeeding art styles such as Constructivism and Suprematism.

An Analysis of Analytical Cubism

Let us now discuss how these artists utilized Analytical Cubism in their works. Georges Braque creates several picture planes to fragment and warp images of a palette, a violin, and sheet music in what might be considered a forerunner of Analytic Cubism – Violin and Palette (1909). The pieces are arranged to accentuate the canvas’s vertical axis, while the restricted color palette emphasizes instead of detracts from the overlapping shapes, producing a density that appears tactile. Braque would further highlight the disassembly of the subject in this fashion, as in Piano and Mandola (1910).

Another notable artwork is Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler (1910) by Picasso. We are able to piece together a picture of Picasso’s sitter by breaking it down into facets and planes, produced in a limited color palette of black, gray, white, and brown. At the bottom of the picture, the observer can see his clenched hands, the loop in his tie, and the nearly geometric meeting of the nose’s bridge and the brows. The subject takes on a sort of density that fades at the margins into the abstract backdrop due to the complexity of the overlapping opaque and translucent surfaces and the limited color palette.

Interpreting Analytical Cubism Artworks

Due to the difficulties in comprehending these near-abstract artworks, numerous reviewers referred to Analytic Cubism as a reclusive discipline. This notion refers to the belief that Analytic Cubism’s language was so groundbreaking that it had no precedent in the history of art and was so hermetic that it had to be mastered from scratch. At the same time, what Picasso referred to as “attributes,” such as the ripple of hair and the clenched hands in his painting, Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler (1910), aided the audience by anchoring the subject to the real world, providing them with a point of reference; in other words, giving the observer “something to build on”.

Analytical Cubism was a revolutionary art style and this new approach to painting challenged old conceptions of depiction and perception, and the public’s reaction was mixed.

Several viewers found Analytical Cubism’s fractured, abstract character difficult to grasp and fully appreciate. Some found the artworks perplexing and found it difficult to connect with them emotionally. Others, on the other hand, were fascinated by this new form of representation and considered it to be a brave departure from traditional art conventions. Analytical Cubism is renowned for its use of subdued hues and flattened space, which can evoke a sensation of detachment or even alienation in certain viewers. For others, though, this harsh visual language was seen as extremely compelling and emotive.

Criticisms and Influence

When the first Analytical Cubism examples appeared in the early 1900s, it elicited varied reactions from the art world. Several artists and scholars supported the concept because they saw it as a revolutionary break from classical representational art. Others were skeptical, believing it to be a type of creative anarchy that contradicted fundamental painting principles.

Criticisms

The subject’s fragmentation and distortion made it difficult for some viewers to understand what they were looking at, resulting in a great deal of bewilderment and criticism. Critics also claimed that Analytical Cubism lacked feeling and failed to elicit an emotional reaction from viewers. Because the focus was on structure and form rather than depiction, there was little place for emotion or sentiment in Analytical Cubism. The style even provoked criticisms of exclusivity and elitism. Several critics contended that the work was purposefully created to alienate the audience and appeal only to a small number of individuals who had the insights and understanding to comprehend it. Cubism was connected by some detractors with political activism and anti-traditional values, leading to suspicions of subversion and even resulting in censorship.

During World War I, for instance, the German government confiscated Cubist paintings on the grounds that they posed a threat to national security.

Influence

In spite of the initial backlash, Cubism went on to establish itself as one of the 20th century’s most significant art styles. It is now widely regarded as a pivotal milestone in the development of contemporary art, with its influence evident across a wide range of creative genres. Analytical Cubism transformed how artists conceive time, space, and representations. The focus on abstraction, fragmentation, and multiple points of view established the foundation for many following art movements, ranging from Surrealism and Abstract Expressionism to Pop Art and Minimalism. Cubism is widely regarded today as a revolutionary approach to creating art, a challenge to established techniques of representation, and a long-lasting influence on the evolution of modern as well as contemporary art.

Impact on Perceptions of Art

Analytical Cubism had a significant and far-reaching influence on traditional concepts of art and representation. It questioned the long-standing legacy of representational painting, which was predicated on the concept of presenting an accurate portrayal of reality. Cubism, on the other hand, tried to depict objects in a more abstract and fractured manner, emphasizing underlying shapes and structures instead of surface appearance.

This called into question the fundamental basis of representational painting, suggesting that reality may be depicted in novel and diverse ways.

Cubism cleared the way for a more experimental and innovative approach to making art. Cubism highlighted the superficiality of perspective and the constraints of the representational painting style by disassembling the object and rearranging it in novel ways. This motivated artists to explore and innovate in their approaches to observing and expressing the environment around them, resulting in a surge of experimentation and invention in the art world.

The Legacy of Analytical Cubism

We have already mentioned the influence that this style had on subsequent art styles, yet the influence of Analytical Cubism’s legacy extends even beyond the world of art. The focus on geometric forms and abstraction in Analytical Cubism has affected the design of houses and buildings, notably in the modernist and post-modernist movements. From the 1920s to the present, fashion designers have drawn inspiration from the geometric forms and bright colors of the style. The fragmented narrative form and numerous perspectives utilized by authors such as Virginia Woolf and James Joyce demonstrate the impact of Analytical Cubism on literary modernism. The fragmentation of form observed in the style has had an impact on musical composition, notably in the performances of composers such as Arnold Schoenberg and Igor Stravinsky.

And with a better understanding of the overall impact of Analytical Cubism, we conclude this article. Analytic Cubism represents the early period of Cubism and the inventions and experimenting of the two painters, Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque. The two artists, known as the “Fathers of Cubism”, altered the face of art. Analytic Cubism paintings, which reached their peak from 1909 to 1912, are distinguished by their fragmented look, linear structure, reduction of color to an almost monochrome color palette, comprehension of objects as fundamental geometric shapes, and utilization of multiple views. Not only has its legacy left a lasting impression on the world of art, but its concepts and ideas have permeated many spheres of life.

Frequently Asked Questions

Who Developed Analytical Cubism?

Analytical Cubism was created in the early 20th century by Pablo Picasso, the famous artist from Spain, and the renowned French artist, Georges Braque. They worked together to break down things into geometric shapes and study them from various angles, resulting in a new art style that changed the art world. The movement first began in 1907 and continued until about 1914.

What Is the Difference Between Analytical Cubism vs. Synthetic Cubism?

Analytical Cubism’s characteristics included monochromatic color schemes, portraying the object’s structure, broken and abstracted shapes, and a use of a limited palette of brown, grays, and black. The emphasis was on analyzing things in the real world and breaking them down into geometric forms and pieces from various points of view. In Synthetic Cubism, the emphasis was on creating new artworks by combining unique elements, materials, and textures in a collage-like fashion. The characteristics of Synthetic Cubism included brighter and more diversified colors, and the utilization of found objects and materials, such as wallpaper and sheet music, to produce collages or assemblages.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Analytical Cubism – Who Developed Analytical Cubism?.” Art in Context. May 18, 2023. URL: https://artincontext.org/analytical-cubism/

Meyer, I. (2023, 18 May). Analytical Cubism – Who Developed Analytical Cubism?. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/analytical-cubism/

Meyer, Isabella. “Analytical Cubism – Who Developed Analytical Cubism?.” Art in Context, May 18, 2023. https://artincontext.org/analytical-cubism/.