De Stijl Art – Exploring the Geometric Art of the De Stijl Movement

The Dutch De Stijl movement developed as a response to the existential heaviness and stress caused by World War I. De Stijl artists pioneered an abstract form of art that was all about geometric designs and solid colors for the sake of finding a deeper and simpler spiritual and “universal” meaning in art and life. These artists expressed themselves through painting, sculpture, architecture, design, and many other modalities. Below, we take a closer look at this avant-garde art (and cultural) movement.

Historical Overview: The Beginnings of “The Style”

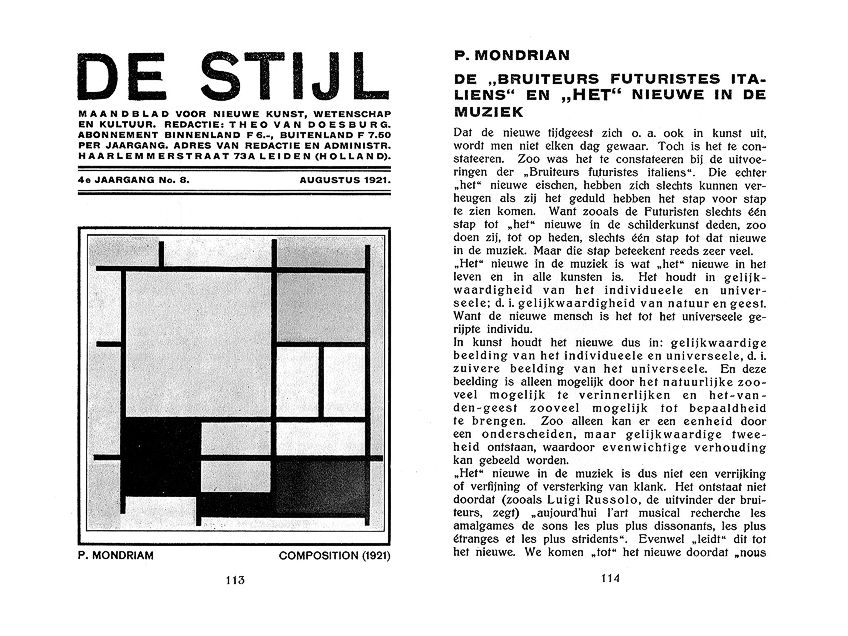

The De Stijl movement began in 1917 in Leiden, which is a city in South Holland in the Netherlands. It lasted until about 1931, which was the year when the founder, Theo van Doesburg, died and the encroaching political unrest from Nazi Germany began. The term De Stijl is Dutch and translates to “The Style” in English.

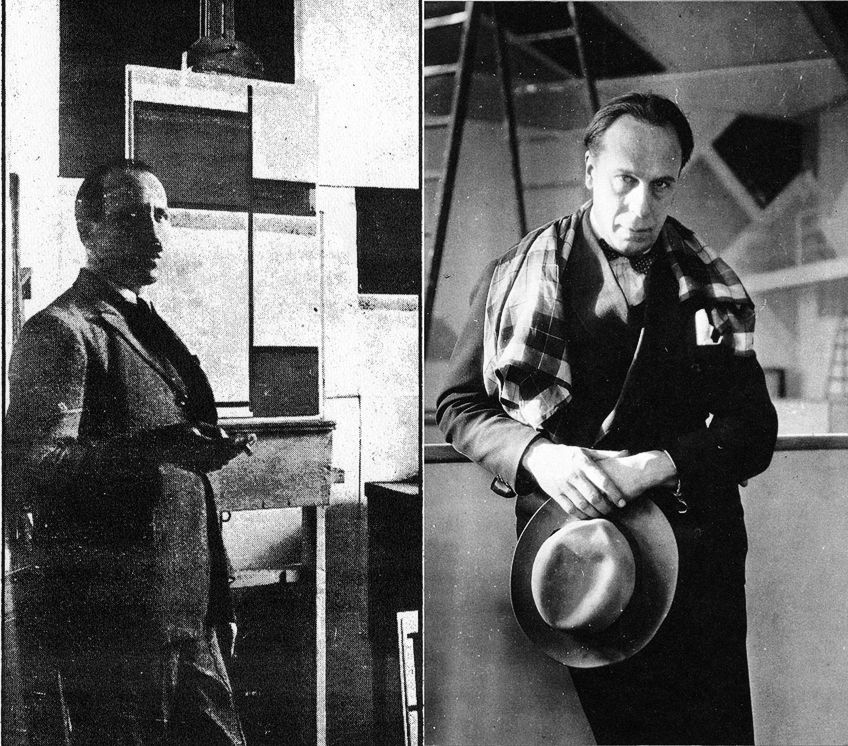

It was Theo van Doesburg, the Dutch architect, designer, and painter who started an art journal called De Stijl. The other primary members and founders were the Dutch painters Piet Mondrian and Bart van der Leck, as well as the Hungarian painter, Vilmos Huszár. The architects J.J.P. Oud, Gerrit Rietveld, and Robert van Hoff were also part of the De Stijl movement.

The idea behind the journal was to bring together like-minded artists, designers, poets, and more to collaborate on a new abstract art style that went beyond painting. It sought to incorporate all types of art modalities like design (for example, industrial design), architecture, furniture design, music, literature like poetry, typography, and more. The journal set the theoretical foundations for the abstracted visual expressions while also giving De Stijl artists a platform to explore and express their theories so that others could be involved and build upon them.

De Stijl became the overall art movement of the time with various other stylistic subsets related to painting and aesthetics within it, such as Neo-Plasticism and Elementarism. In fact, it was a whole new “style”.

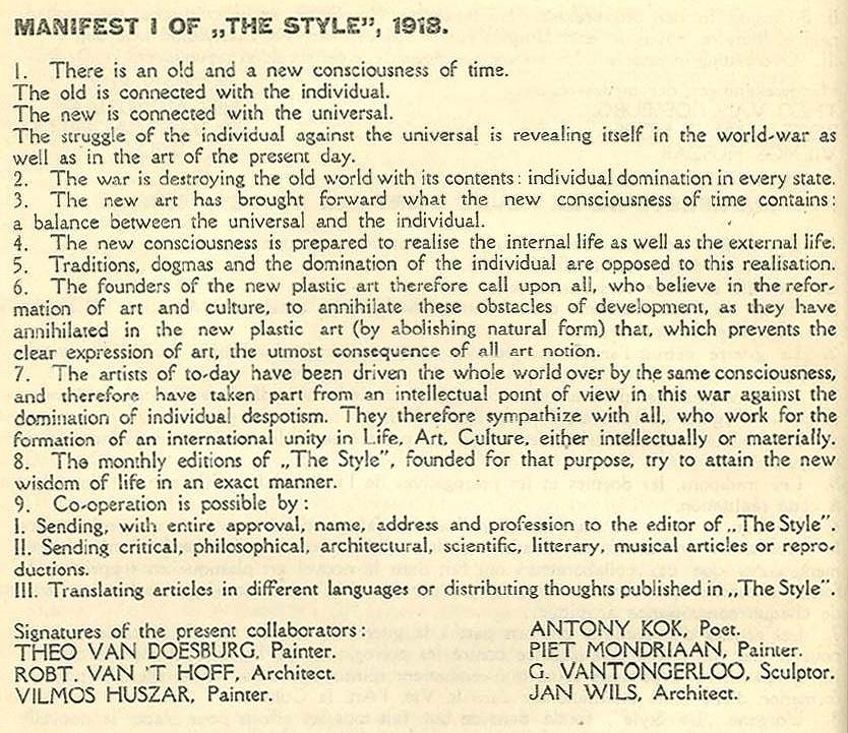

In the year 1918, De Stijl members published a manifesto outlining nine principles about what the De Stijl movement stood for. De Stijl’s primary goal is often quoted, which succinctly sums up the movement: “the organic combination of architecture, sculpture, and painting in a lucid, elemental, unsentimental construction”.

Some of the points described the old and new consciousness of the time, as well as the focus on the individual and the universal, for example, “the struggle of the individual against the universal is revealing itself in the world-war as well as in the art of the present-day”. The movement was therefore a “reformation” of art and culture.

What Influenced the De Stijl Movement?

The De Stijl movement developed as a response to the existential and societal heaviness that came from World War I. It was a desire for a Utopian world, a world that was harmoniously ordered. Spiritual ideas pervaded the overarching ideals of this movement.

In other words, where there was a tendency towards more expressionism because of the socio-political circumstances in Europe during the early 1900s, De Stijl moved in the other direction.

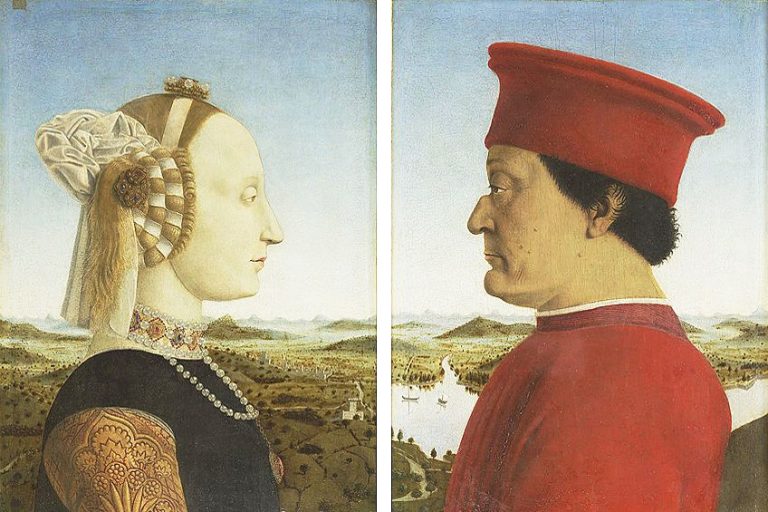

It aimed to create a movement based on fundamental, non-figurative ideas, as well as a spiritual essence of simplicity and geometry underpinning each visual work. The De Stijl movement was influenced by the ideas of several other art movements that existed before it.

Influences include the Cubists like Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, who pioneered the more abstracted expression of forms. Another influential art movement is the Russian-based Suprematism, which was an abstract art movement founded by Kazimir Malevich in 1915. It was focused on the non-objectivity of art and geometric shapes. Additionally, the Russian-based Constructivism also influenced De Stijl, which was founded in 1915 by Vladimir Tatlin and Alexander Rodchenko. Constructivism had an especially great influence on De Stijl architecture.

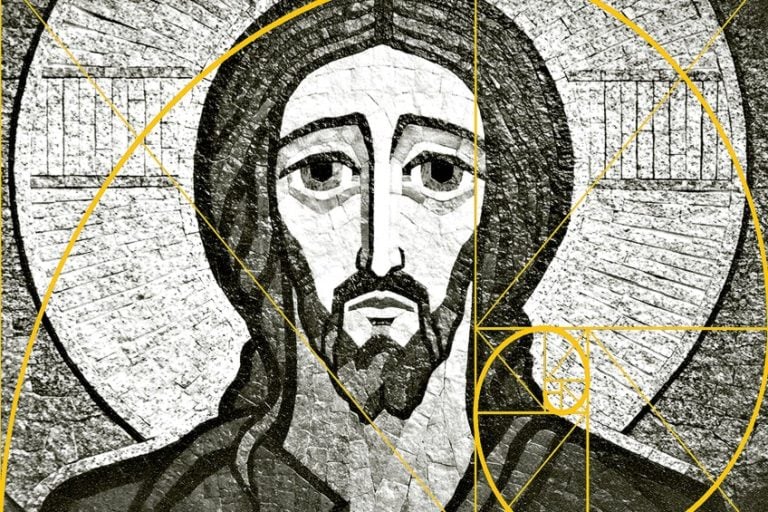

The Theosophical Society

The Theosophical Society, which was founded in 1875 by Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, was another school of thought that influenced the De Stijl movement. It had other members like Rudolf Steiner who eventually took on the role of General Secretary in Germany.

The ideas behind M.H.J. Schoenmaekers’ philosophy explored universal truths through simple and “ideal geometric” forms. It is also described as a “mystical” ideology by some sources.

The Neo-Platonic ideas from Schoenmaekers influenced De Stijl artists, especially Piet Mondrian, who established his art theory and visual style called Neo-Plasticism, meaning “New Plastic.” Schoenmaekers’s publications, Het Nieuwe wereldbeeld (“The New Image of the World”, 1915) and Beginselen der beeldende wiskunde (“Principles of Plastic Mathematics”, 1916) were particularly influential resources.

Schoenmaekers’ quote is often used to describe the influence he had on De Stijl artists ideas of form, where he said: “The two fundamental and absolute extremes that shape our planet are: on the one hand the line of the horizontal force, namely the trajectory of the Earth around the Sun, and on the other vertical and essentially spatial movement of the rays that issue from the center of the Sun…the three essential colors are yellow, blue, and red”.

Towards the De Stijl Art Definition

The De Stijl art definition can be better defined if we look at the artworks produced during this time. Each piece is a physical manifestation, and therefore definition, of what the movement was. However, knowing what the movement stood for will also help us understand the De Stijl art definition.

So, let us look at some of the characteristics and styles of this movement, as well as a few of the primary artists and their artworks.

De Stijl Art Characteristics, Styles, and Artworks

According to the Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) Bulletin (Volume XX, No. 2, Winter, 1952 to 1953), the De Stijl movement is characterized by three “fundamental” principles. These are, “in form the rectangle; in color the “primary” hues, red, blue and yellow; in composition the asymmetric balance”.

This was at the heart and soul of the De Stijl movement, and to better understand it we need to look at two styles within the movement.

There were two important styles within the De Stijl movement, and it is important to recognize that these were not synonymous with the overall movement called De Stijl, but they were products of it and applied by De Stijl artists. It became a seeming battle between the lines of Piet Mondrian and Theo van Doesburg. We had Mondrian opting for horizontal and vertical and van Doesburg going for diagonals. Below, we explore the main tenets of each style.

Mondrian’s Neo-Plasticism

Mondrian’s quote from his essay, Neo-Plasticism in Pictorial Art (1917 to 1918), captures the essence of what he believed in; it was also through this essay that he introduced Neo-Plasticism. In it, he stated, “As a pure representation of the human mind, art will express itself in an aesthetically purified, that is to say, abstract form. The new plastic idea cannot, therefore, take the form of a natural or concrete representation”.

Mondrian was influenced by his prior involvement in the Neo-Impressionism style and the color theory work done by its leading member, Georges Seurat. Mondrian also utilized his strong beliefs in theosophy to guide him in creating the fundamentals of Neo-Plasticism. He was a member of the Dutch Theosophical Society.

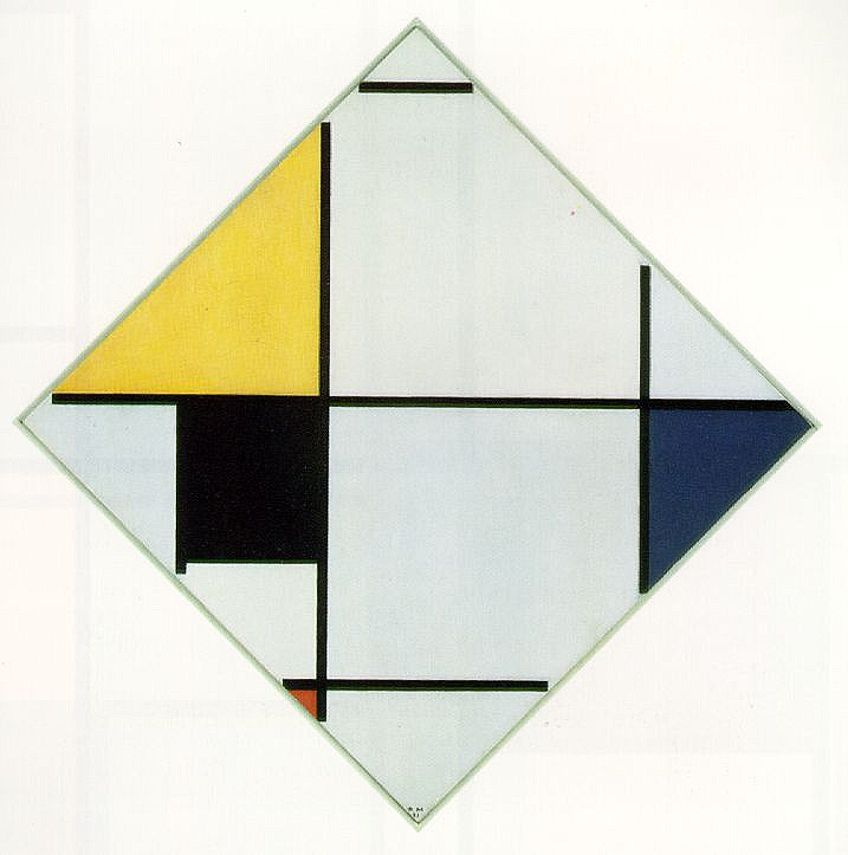

Some of the characteristics of Neo-Plasticism include strict adherence to geometric shapes within a composition.

Shapes include horizontal and vertical lines, or straight lines and rectangles. The surface of the composition, or the canvas, also needed to be a rectangular shape. Sometimes Mondrian tilted the canvas at an angle (45 degrees), and these De Stijl paintings are known as his Lozenge series.

There was also a focus on asymmetry – Mondrian believed that harmony or balance would be created through the positioning of geometric shapes. No other shapes like circles were allowed in compositions, including any diagonals or curved lines.

Colors were also strictly primary colors (red, blue, and yellow), which would be used against a background of primarily solid colors like white, black, or grey. There was also a balance between stark colors and stark lines, otherwise also described as “bold”.

Neo-Plasticism was Mondrian’s aim to portray “absolute reality”. It was a reduction of all, of what was believed unnecessary, such as elements of painting like subjectivity or representation and other compositional techniques like perspective. It was to convey a sense of purity by returning to fundamental shapes and colors.

Although most De Stijl artists prescribed to Neo-Plasticism, as the principles were outlined in the De Stijl journal, many started to feel that this was too restrictive. From around the years 1921 to 1924, Theo van Doesburg broke away from the Neo-Plasticism style and started his own style called Elementarism.

This led Mondrian to gradually break away from De Stijl, choosing to continue Neo-Plasticism and develop the style independently.

The style developed throughout Mondrian’s time in Paris from 1919 to 1938, and then London, from 1938 to 1940. Because of the war, he moved to New York and lived there, where his artwork reached new levels of inspiration.

Van Doesburg’s Elementarism

Van Doesburg’s Elementarism included diagonal lines, which held symbolic meaning for the artist, related to movement and “dynamism”. By adding diagonals and playing with various shades of colors, van Doesburg’s artworks had a sense of liveliness. Many sources also indicate that van Doesburg was more extroverted than Mondrian and their disagreements were because of stylistic preferences, which could be from personality dispositions.

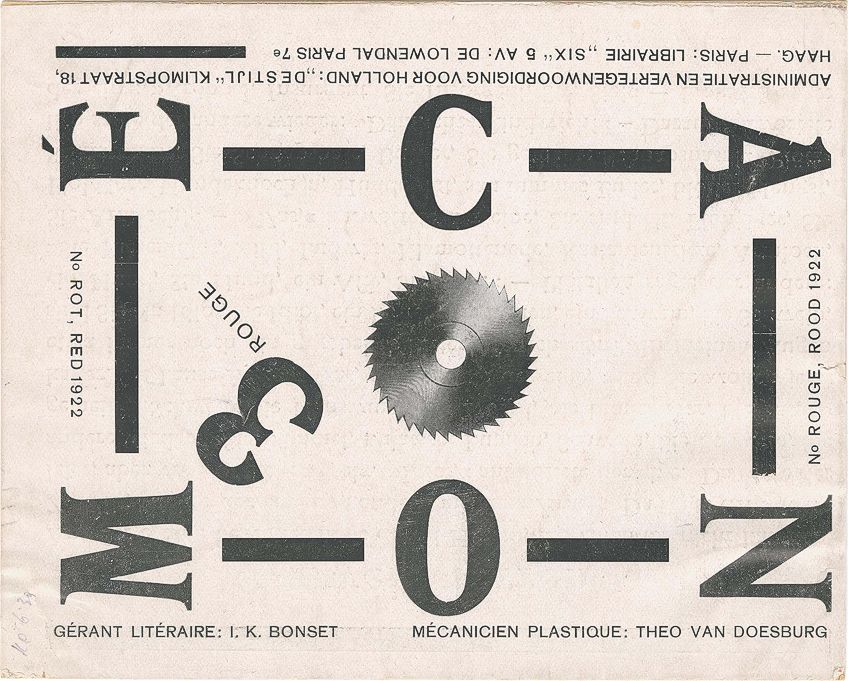

Furthermore, van Doesburg was involved in other artistic pursuits and styles, such as the Dada art movement, which he was a part of for a period. Van Doesburg also wrote and edited for the magazine, Mécano. He wrote Dada poetry under the pseudonym, I.K. Bonset. He also lectured at the Bauhaus school during the year 1921 and collaborated with various architects like Cornelis van Eesteren and J.J. Oud, producing many dynamic artworks over the years.

The core ideals of Elementarism were written in the Elementarism manifesto by van Doesburg, titled Manifesto of Elementarism (1926 to 1928), including other essays written for the De Stijl journal. A notable difference in van Doesburg’s style was his fusion between painting and architecture. He wrote about this in the essay titled, Towards a Collective Construction (1924), stating:

“We declare that painting without architectural construction (that is, easel painting) has no further reason for existence.”

Famous De Stijl Artists and Artworks

There were numerous De Stijl artists, ranging from painters, designers, architects, sculptors, and more. Below, we look at a few of the famous De Stijl artworks that are testament to the movement’s principles and avant-garde nature within the art world, which also opened new forms of art into the Modern world.

Piet Mondrian (1872 – 1944)

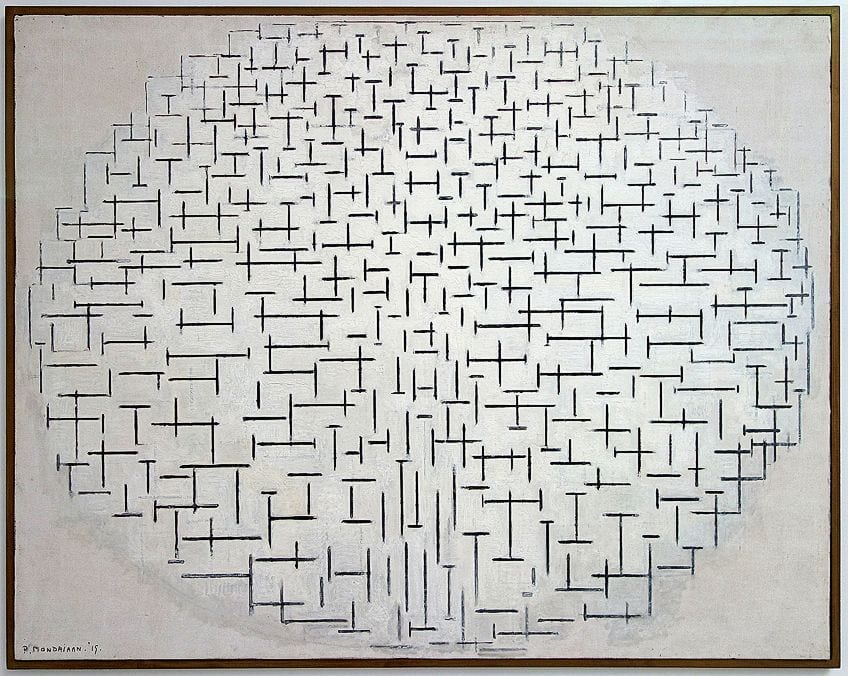

Piet Mondrian’s earlier artworks were Cubist experimentations and styles, as in the oil painting, The Gray Tree (1912). We see the shape of a tree – the start of an abstracted composition – emphasized by the lines and solid colors like black and gray. His work Pier and Ocean (Composition No. 10) (1915) shows a clear abstracted image, with minimal reference to the natural world. We also notice how Mondrian composes his vertical and horizontal lines in the space.

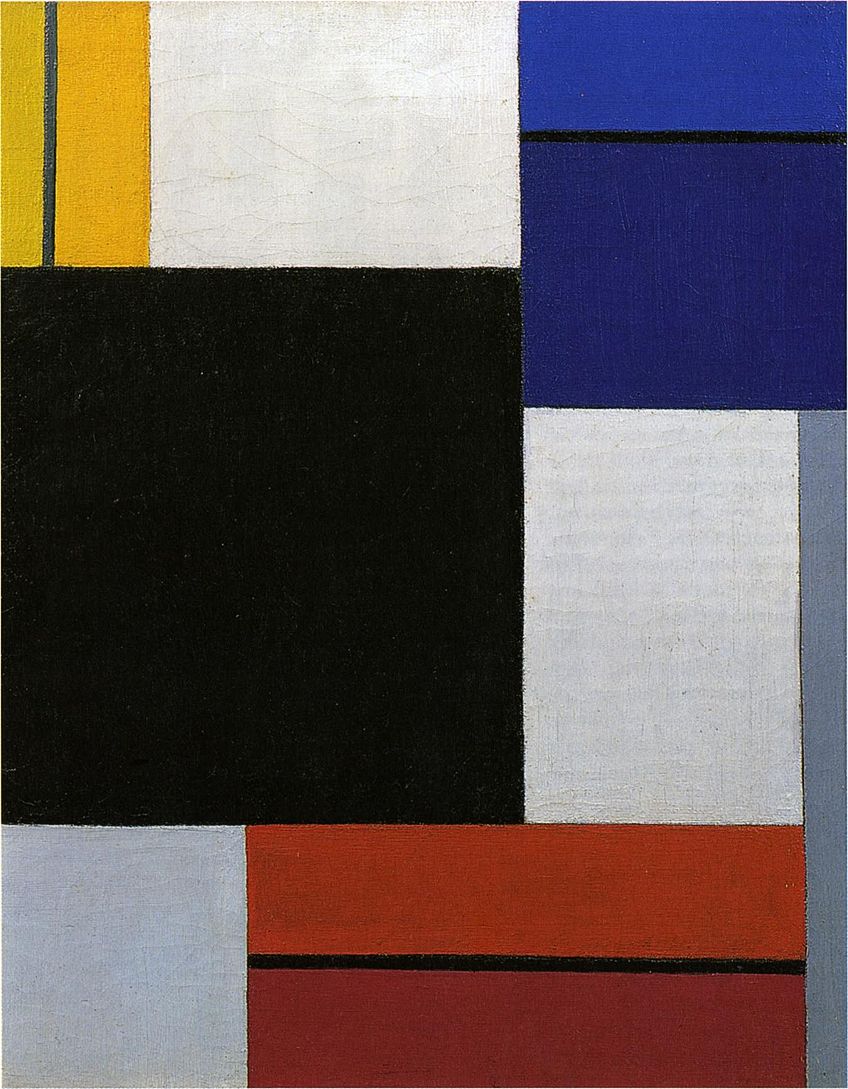

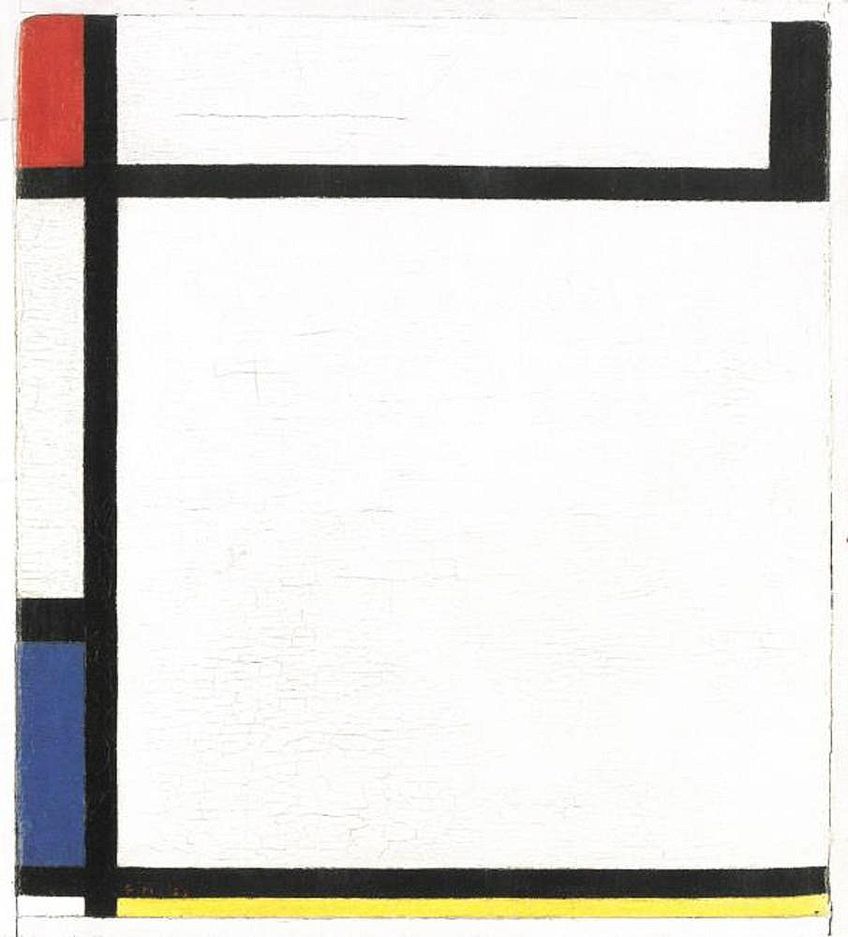

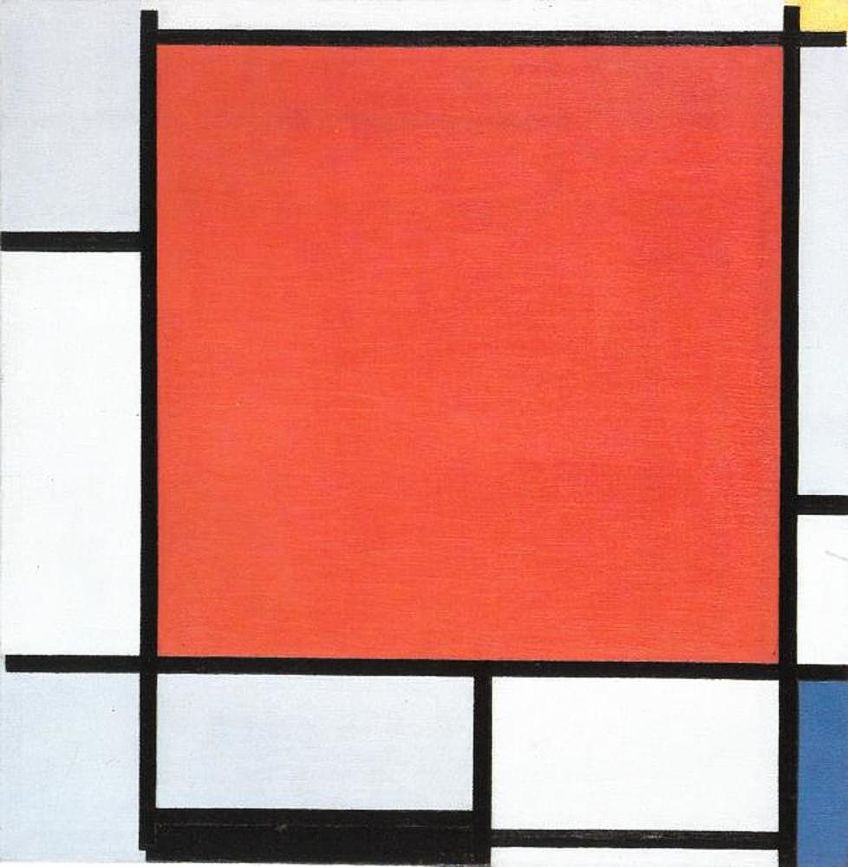

We start seeing the characteristic De Stijl style in Mondrian’s oils, Composition with Color Planes (1917) and Composition with large red plane, bluish gray, yellow, black, and blue (1922). In both paintings, the artist depicts square planes of color in seeming balance and harmonious structure on the canvas.

However, the first painting has lighter colors while the latter painting has brighter colors, still sticking to the primary color scheme.

In Composition with large red plane, bluish gray, yellow, black, and blue, we notice more refinement in Mondrian’s style. There is a large red square in the center of the composition with various surrounding white blocks and some of color. Thick black lines outline the squares, making them stand out even more. Furthermore, there is an asymmetry created due to the large and small blocks.

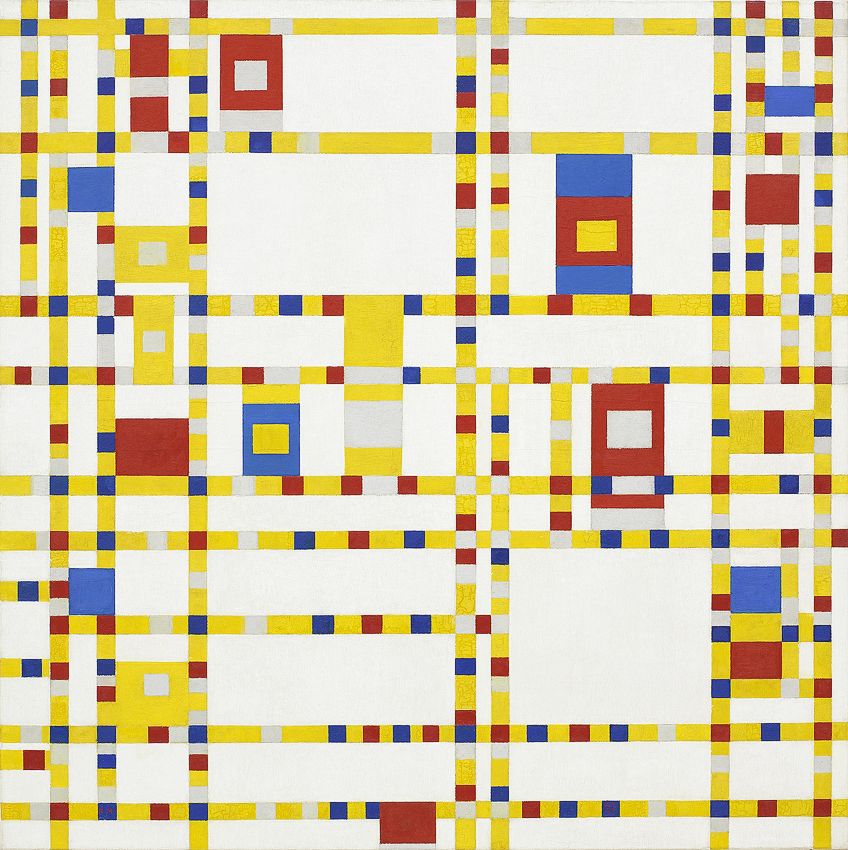

Other artworks by Mondrian include his Composition II Red, Blue, and Yellow (1930), his Lozenge series of paintings, Tableau I: Lozenge with Four Lines and Gray (1926), and his later oil painting called Broadway Boogie-Woogie (1942 to 1943), which was more dynamic than his previous paintings. The latter was also one of his artworks from when he lived in New York, showing a change in the artist’s style and utilization of colors and form.

This is often attested to the lifestyle change of living in one of the largest and culturally diverse and upbeat cities in the world, as well as the influence of Jazz, which was prevalent at the time.

Theo van Doesburg (1883 – 1931)

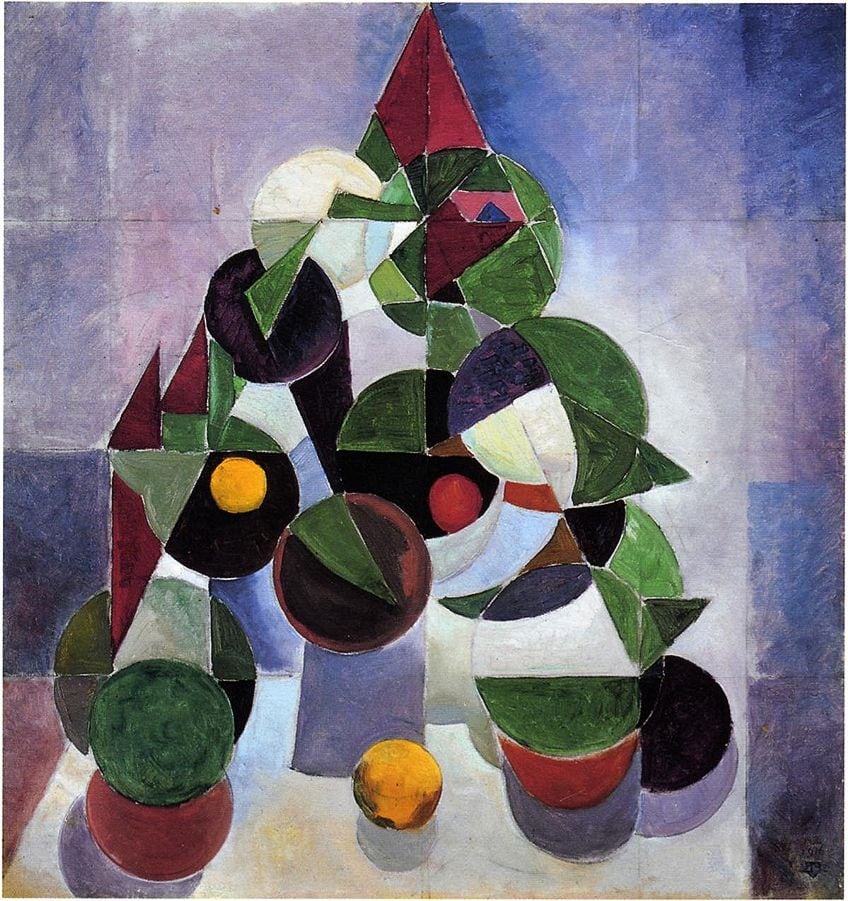

Theo van Doesburg, the founder of the De Stijl movement, produced numerous examples of how abstracted forms relate to the overall message of the movement. We see this in his early works, Composition VIII (The Three Graces) (1917) and Composition VIII (The Cow) (c. 1918). Although the titles suggest forms from the natural world, in the oil painting the artist reduced the subject matter to its fundamental shapes.

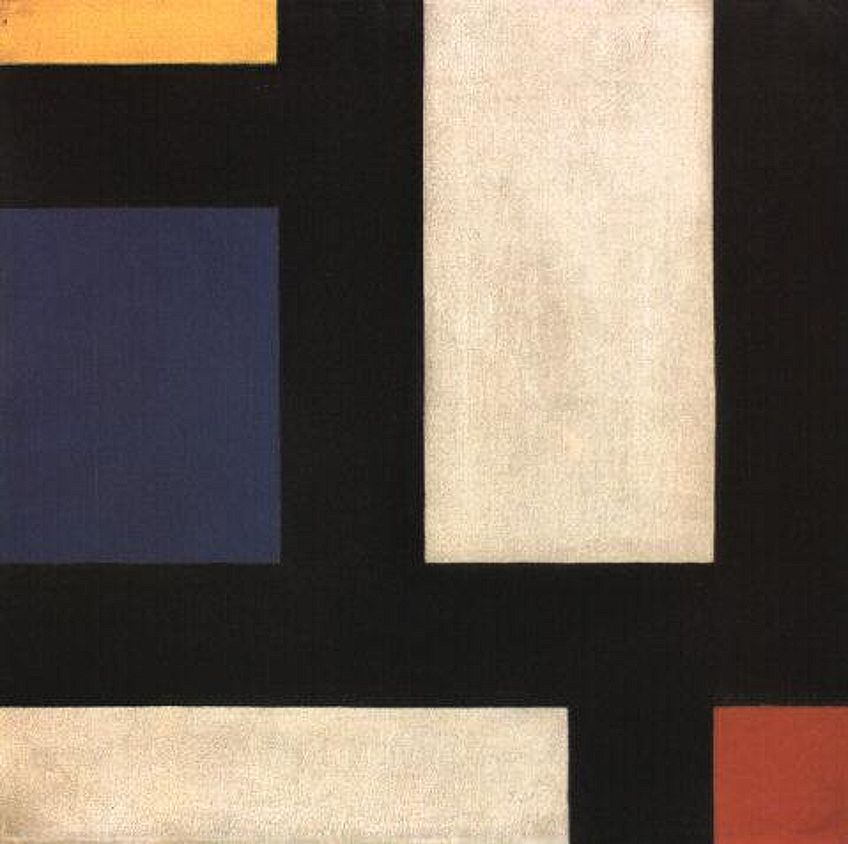

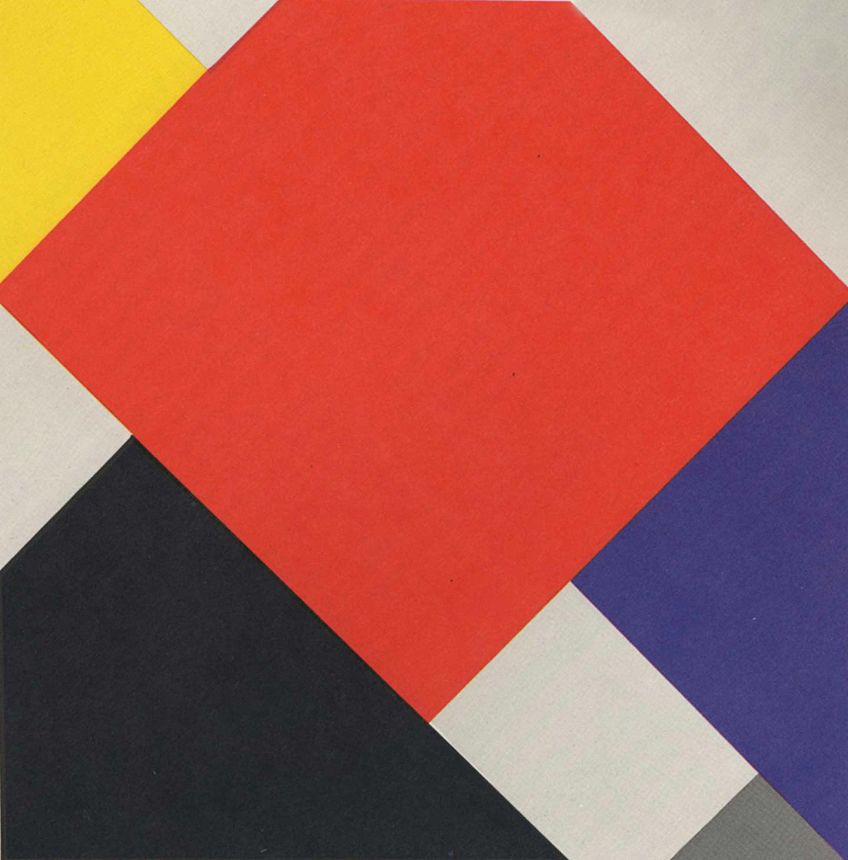

Van Doesburg also created his signature “Counter-Composition” series, which started to move away from the strict compositional structures set out by Mondrian.

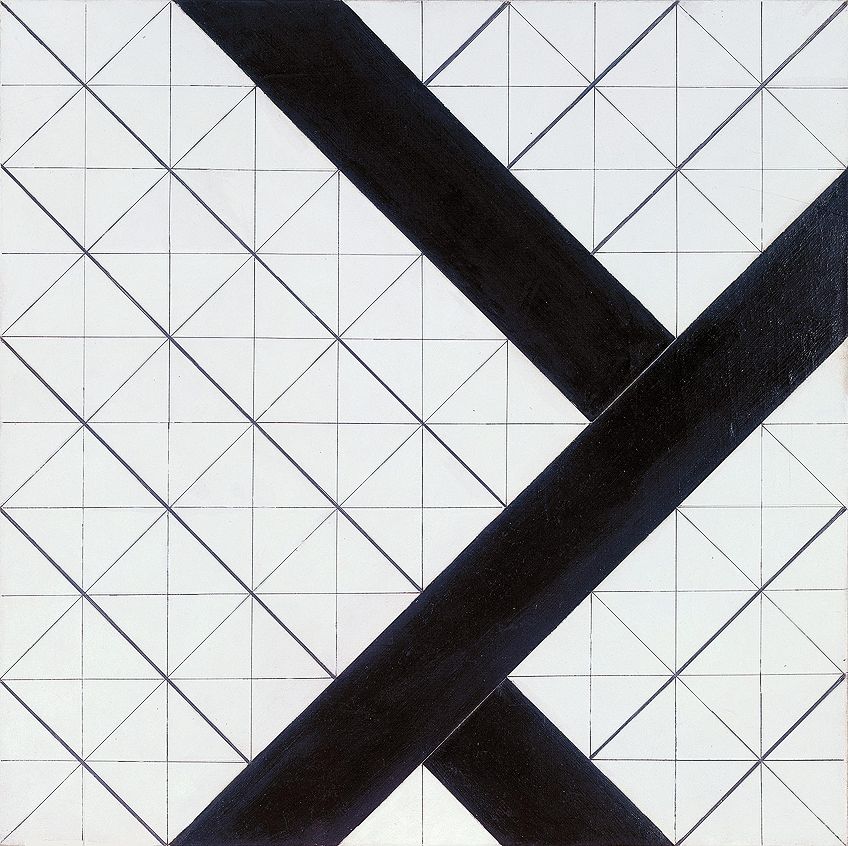

Examples from this series include Counter-Composition V (1924), Counter-Composition VIII (1924), Counter-Composition VI (1925), and Counter-Composition in Dissonance XVI (1925). We will notice the characteristic De Stijl painting diagonals in these oil paintings.

For example, in Counter-Composition V, we notice almost exact similarities between Mondrian’s paintings, but here, van Doesburg flipped the geometric shape to 45 degrees. We also see the characteristic primary colors, with an additional gray in the bottom right corner of the composition. There are also no black lines between the shapes.

In Counter-composition VI, we notice black lines moving in almost every direction and plane. As the background, there is a grid with noticeable vertical and horizontal lines, and overlapping this is another grid with diagonal lines. Dominating most of the right side of the oil painting are three thick black strips along the diagonal grid. This painting also shows how the background grid is lighter in color, the diagonal grid is bolder in color, and the forefront significantly highlights the black strips.

Furthermore, the composition appears almost like an architectural plan or grid, suggesting the artist’s interest beyond painting.

In Simultaneous Counter-Composition, we notice an almost playful version of one of Mondrian’s paintings. Van Doesburg has utilized the typical primary colors, squares, and black lines, but here he has not stayed within the lines, so to say. We notice the white background, black, blue, red, and yellow squares, and what appears to be black lines for a border. The blocks are not positioned neatly alongside the other and the black lines are overlapping the square shapes, all as if the whole piece were knocked over, causing the shapes to come loose from the black lines, which evidently appear diagonal, connected by a right angle.

Gerrit Rietveld (1888 – 1964)

Gerrit Rietveld was an architect and furniture designer. He is well-known for his Red and Blue Chair (1923), which became a symbol for De Stijl’s style, also showing us its application across media beyond the canvas. This chair is designed with detailed precision in its color, lines, and planes. Rietveld did not intend for any parts to intersect with the other, but simultaneously there is an interplay of each part. It is also made in a manner that suggests mass production. There is also an element of stylistic design over comfort.

Other works by Rietveld include his classic example of De Stijl architecture, the Rietveld Schröder House (1924). Here, we notice the style so characteristic of the De Stijl movement, again going beyond the canvas and being applied to buildings (this is a clear example of art and architecture becoming a unified force).

The house appears as a three-dimensional version of a De Stijl painting; we notice the primary colors yellow, blue, and red in the beams near the windows and the larger areas of white, gray, and black that make up the outer walls of the house.

More De Stijl Artists

Other De Stijl artists include Vilmos Huszár, who was a Hungarian painter, well known for his oil paintings in the De Stijl movement like Mechano-Dancer (1922), which is different in style from the original Neo-Plastic style. There appears to be a form or shape suggestive of a body or human-like form. We also notice a freer utilization of the horizontal, vertical, and diagonal lines with a subdued color scheme.

Other De Stijl artists were architects and visual arts designers, such as the painter and ceramicist Bart van der Leck, who was a quiet and reserved member of the De Stijl movement. Van der Leck eventually left the movement in 1920, not signing the De Stijl manifesto.

Leading members in De Stijl architecture were J.J.P. Oud, who was the Municipal Housing Architect for Rotterdam from 1918 to 1933. Then there was Robert van Hoff, who designed furniture in addition to architecture. He also provided financial assistance to the De Stijl journal.

Other members were Jan Wils, an architect, Georges Vantongerloo, César Domela, Cornelis van Eesteren, and Ilya Bolotowsky, who was a painter of Russian descent. He was influenced by Piet Mondrian and his characteristic vertical, horizontal, and primary color scheme style of art. Bolotowsky painted in this manner too and was a pioneer in developing the growth for abstract artists through the American Abstract Artists association.

De Stijl and Beyond: Towards the Modern

The De Stijl movement came to an end around the time when van Doesburg died in the early 1930s. Although this may have put a stop to the movement, it was kept alive by what van Doesburg contributed and started within the movement, along with many of the other artists, who all developed in their own way artistically. The De Stijl movement influenced Modern Art, the International Style in architecture, the Bauhaus movement, and many other modern artists like Mark Rothko, Frank Stella, Dan Flavin, and Donald Judd.

De Stijl, and everything it stood for, gave not only painting but design and architecture a new meaning. With its strong theoretical and contemplative focus, it challenged the way artists of all modalities viewed art and the interaction and relationship with form, color, and composition – in three dimensions or two, and the merging of the mystical and spiritual. It was almost a “back-to-basics” style of art that sought the underlying truth when all excess of form was removed.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Was the De Stijl Movement?

The Dutch architect, designer, and painter, Theo van Doesburg, started an art journal called De Stijl. The journal set the theoretical foundations for the abstracted visual expressions, it also gave De Stijl artists a platform to explore and express their theories. De Stijl is the term designating the art movement in the Netherlands during the 1900s. It had two subset styles, namely, Neo-Plasticism and Elementarism.

What Are the Main Characteristics of De Stijl Art?

The main characteristics of the De Stijl movement can be viewed as three “fundamental” principles. These are geometric forms, in other words, vertical and horizontal lines and rectangles; a color palette of only primary colors, red, blue, yellow, and solid colors like black, white, and gray; and an asymmetrical composition, which achieves a balance.

What Does “De Stijl” Mean?

The term De Stijl is a Dutch word that translates to “The Style” in English. It was the name given to the Dutch art journal, which was started in the early 1900s by Theo van Doesburg and Piet Mondrian, among other Dutch artists, architects, sculptors, and designers.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “De Stijl Art – Exploring the Geometric Art of the De Stijl Movement.” Art in Context. August 25, 2021. URL: https://artincontext.org/de-stijl-art/

Meyer, I. (2021, 25 August). De Stijl Art – Exploring the Geometric Art of the De Stijl Movement. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/de-stijl-art/

Meyer, Isabella. “De Stijl Art – Exploring the Geometric Art of the De Stijl Movement.” Art in Context, August 25, 2021. https://artincontext.org/de-stijl-art/.