Wassily Kandinsky – A Portrait of Kandinsky the Artist

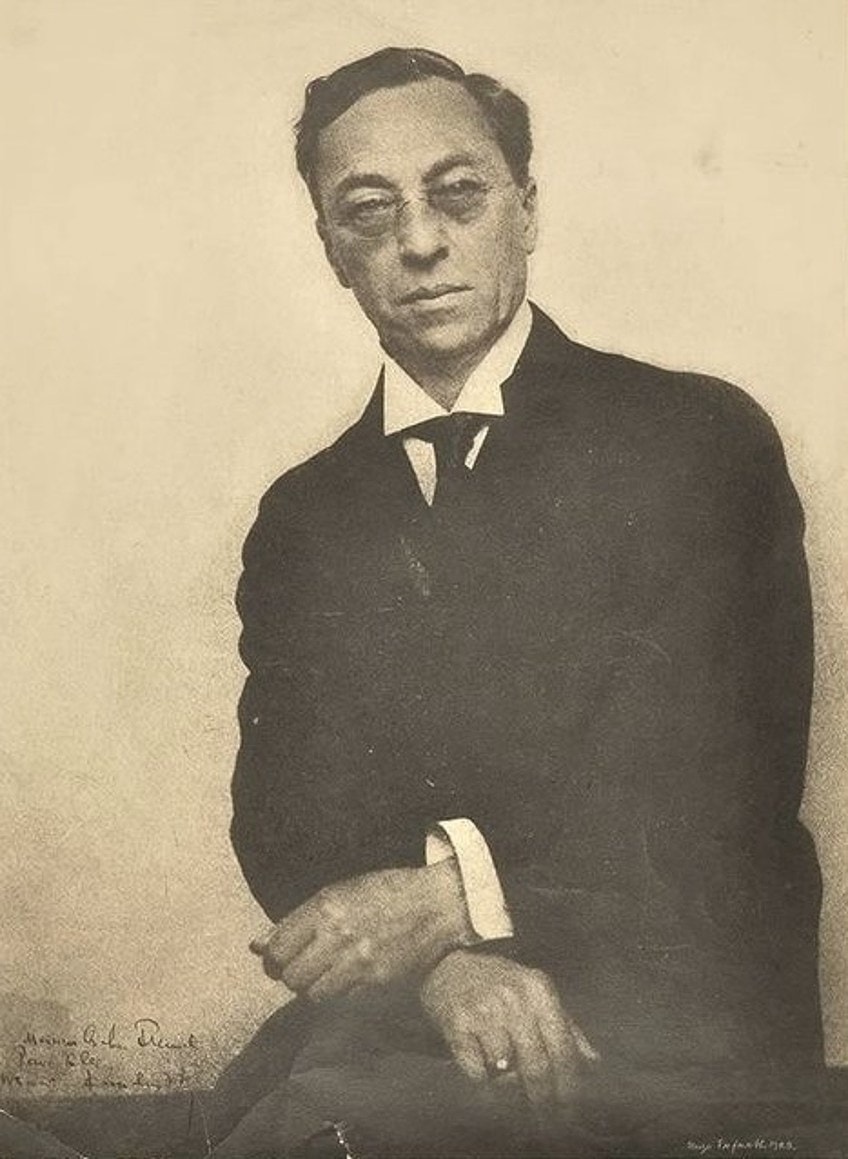

Russian abstract artist Wassily Kandinsky popularized abstract painting in the last years of the19th century and early years of the 20th century. Kandinsky the artist stressed the integration of the visual and aural in his unique viewpoint on the form and purpose of art. He perceived noises as colors, and this odd perspective influenced the creation of Kandinsky’s artworks. Kandinsky the painter believed that the aim of art was to transmit the artist’s uniqueness and inner vision, which necessitated the elevation of objective reality. Kandinsky’s paintings sought to demonstrate that absolute abstraction allowed for deeper, sublime insight and that imitating nature simply hampered this endeavor.

Wassily Kandinsky’s Biography and Artwork

Kandinsky the artist’s work progressed through three stages, starting with his early, realistic paintings and their celestial symbolism, then to his ecstatic and theatrical compositions, and lastly to his late, geometric, and biomorphic flat color surfaces. Kandinsky’s works and ideas impacted several generations of painters, from his Bauhaus students through the Abstract Expressionists after WWII. Above all, Kandinsky’s works were deeply spiritual.

Kandinsky the painter aspired to transmit profound mysticism and the profundity of human emotion through a worldwide visual media of geometric forms and colors that transcend cultural boundaries. Kandinsky’s abstract work was the culmination of a lengthy period of serious contemplation based on his creative experiences.

He dubbed this dedication to inner attractiveness, spiritual zeal, and mental yearning as “inner need,” and it was a major part of Kandinsky’s art.

| Date Born | 16 December 1866 |

| Date Died | 13 December 1944 |

| Place Born | Moscow, Russia |

| Associated Movements | Abstract Art, Expressionism |

Early Life

Russian abstract artist Kandinsky was born in Moscow, the son of tea trader Vasily Silvestrovich Kandinsky and Lidia Ticheeva. While in Moscow, Kandinsky learned from a number of influences. While at school, he studied a variety of subjects, including business and law. He would later recollect being intrigued and motivated by color as a youngster. His concern with symbols and psychoanalysis intensified as he grew older. He was a member of an anthropological study party that traveled to the Vologda area north of Moscow in 1889.

The houses and churches were painted with such glittering colors that he thought he was inside a picture when he entered them.

This encounter, as well as his research into the region’s traditional art (especially the use of brilliant colors on a dark background), influenced much of his initial studies. A few years afterward, he first compared paintings to the type of music composition for which he would become famous, stating:

“The keyboard is color, the eyes are hammers, and the heart is a piano with several strings. The musician is the hand that plays, feeling one note or another in order to create vibrations in one’s soul.”

At the age of 30, Kandinsky left a job lecturing on law and business to attend the Munich Academy, where his tutors included Franz von Stuck. He was not admitted right away and had to learn painting on his own. Before leaving Moscow in 1920, he viewed an exhibit of Monet’s works. He was notably attracted by Haystacks‘ impressionistic technique, which he saw as having a vivid sense of color practically independently of the things themselves.

He would subsequently reflect on this encounter: “The brochure advised me that it was a haystack. I had no idea what that was. This non-recognition was excruciatingly distressing for me. The painter, in my opinion, had no right to depict incoherently. I had a distinct impression that the painting’s subject was absent. And I was surprised and perplexed to discover that the image not only captivated me but also left an indelible imprint on my mind. The painting gained a fairy-tale-like force and magnificence.”

During this time, Kandinsky was also affected by Richard Wagner’s Opera, “Lohengrin” (1850), which he thought stretched the boundaries of melody and song beyond ordinary lyrical.

Madame Blavatsky, the most well-known proponent of theosophy, also had a spiritual impact on him. According to theosophical philosophy, existence is a geometric sequence that begins with a single point. A falling succession of spheres, squares, and triangles expresses the form’s generative nature.

Career

Kandinsky asked Gabriele Münter to accompany him at his summer art seminars in the Alps located close to Munich in the summer of 1902. She agreed, and their connection shifted from business to personal. Kandinsky found art school, which is typically thought to be challenging, to be simple.

During this period, he began to establish himself as a theorist of art and an artist.

At the start of the 20 century, the number of his remaining works rose; much survives of the landscapes and cities he produced, utilizing vast swathes of color and identifiable features. Kandinsky’s paintings, for the greater majority, did not include any human beings; an anomaly is Sunday, Old Russia (1904), in which Kandinsky reconstructs a vibrant scene of villagers and nobility in front of a city’s main walls.

Metamorphosis

Couple on Horseback (1907) displays a man on horseback tenderly hugging a lady as they ride by a Russian village with glowing walls across a turquoise river. The horse is subdued, but the foliage on the trees, the village, and the reflection in the river sparkle with splashes of color and brightness. The way the field of view is condensed into a flat, luminous surface in this painting displays the impact of pointillism. Fauvism may be seen in these early pieces as well. Colors are utilized to represent Kandinsky’s perspective with the subject matter rather than to depict objective nature.

The Blue Rider (1903), depicting a little shrouded man on a racing horse riding over a rocky landscape, was one of his most important works from the first decade of the 20th century. The rider’s cape is a moderate blue with a deeper blue shadow. The opposites to the autumn trees in the backdrop are more hazy blue shadows in the front. The blue rider is conspicuous (although not completely defined) in the artwork, and the horse moves in an unusual manner (which Kandinsky was surely aware of). Some art scholars concur that the rider is holding a second person (possibly a child), however, this might be a shadow cast by the lone rider.

This deliberate disjunction, which allowed spectators to engage in the construction of the work, became a more deliberate method utilized by Kandinsky in later years, culminating in the abstract works from 1911 until 1914.

Kandinsky depicts the riders on horseback in The Blue Rider as a stream of colors rather than in particular detail. When compared to contemporaneous painters, this picture is not unique in that sense, but it suggests the route Kandinsky would follow only a few years later. From 1906 through 1908, Russian abstract artist Kandinsky traveled extensively over Europe (he was a member of Moscow’s Blue Rose symbolist movement) before settling in the little Bavarian town of Murnau.

In 1908, he purchased a copy of Charles Webster Leadbeater and Annie Besant’s Thought-Forms. He entered the Theosophical Society in 1909. At this period, he produced The Blue Mountain (1909), illustrating his move toward abstractions.

A blue mountain is framed by two wide trees, one red and the other yellow. At the base, a group of three cyclists and numerous more crosses. The riders’ faces, clothes, and saddles are all one color, and neither they nor the strolling characters have any actual detail. Fauvist inspiration may also be seen in the flat surfaces and curves. The Blue Mountain‘s extensive use of color exemplifies Kandinsky’s preference for an artwork in which color is portrayed irrespective of form and in which each hue is given equal emphasis.

The arrangement is flatter, with four sections: the yellow tree, the red tree, the sky, and the blue mountain with the three horsemen.

The Blue Rider Period

Kandinsky’s paintings from this time are huge, emotive colored masses that are judged independently of shapes and lines; these no longer serve to delimit them, but instead, overlap freely to produce paintings of tremendous energy. Because music is abstract in essence does not aim to portray the outside world, but conveys the inner sensations of the soul in an instantaneous way—it was vital in the formation of abstract art.

Kandinsky’s works were occasionally identified using musical terms; he labeled his most impulsive canvases “improvisations” and more sophisticated ones “compositions.”

Kandinsky the painter was also an art theorist; his theoretical writings may have had a greater impact on the history of Western art than his artworks. He was a founding member of the Munich New Artists’ Association and served as its president in 1909. However, the group was unable to merge Kandinsky’s unconventional attitude with traditional aesthetic notions, and the organization disbanded in late 1911.

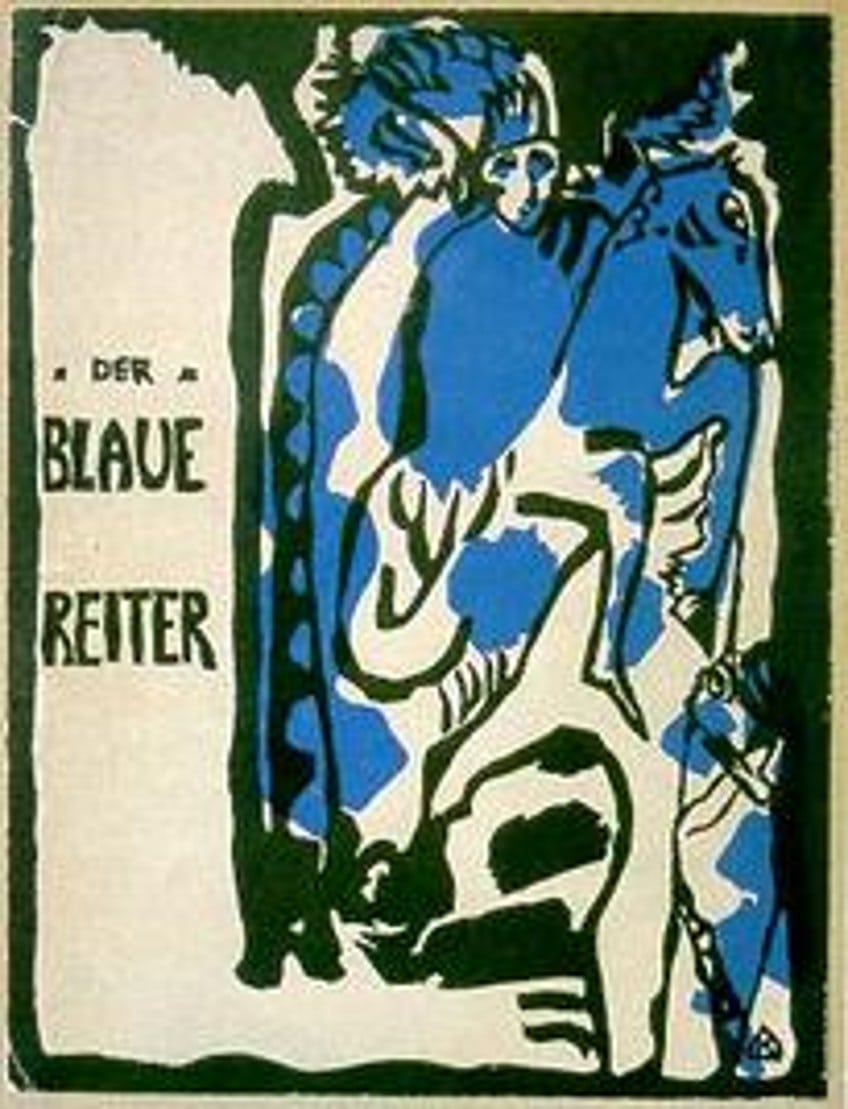

Kandinsky then founded the Blue Rider with painters including Franz Marc, August Macke, Albert Bloch, and Gabriele Münter.

The Blue Rider Almanac was published in 1912, and two displays were conducted. More of each were planned, but the advent of World War I in 1914 put a stop to these ambitions, sending Kandinsky back to Russia via Switzerland and then on to Sweden.

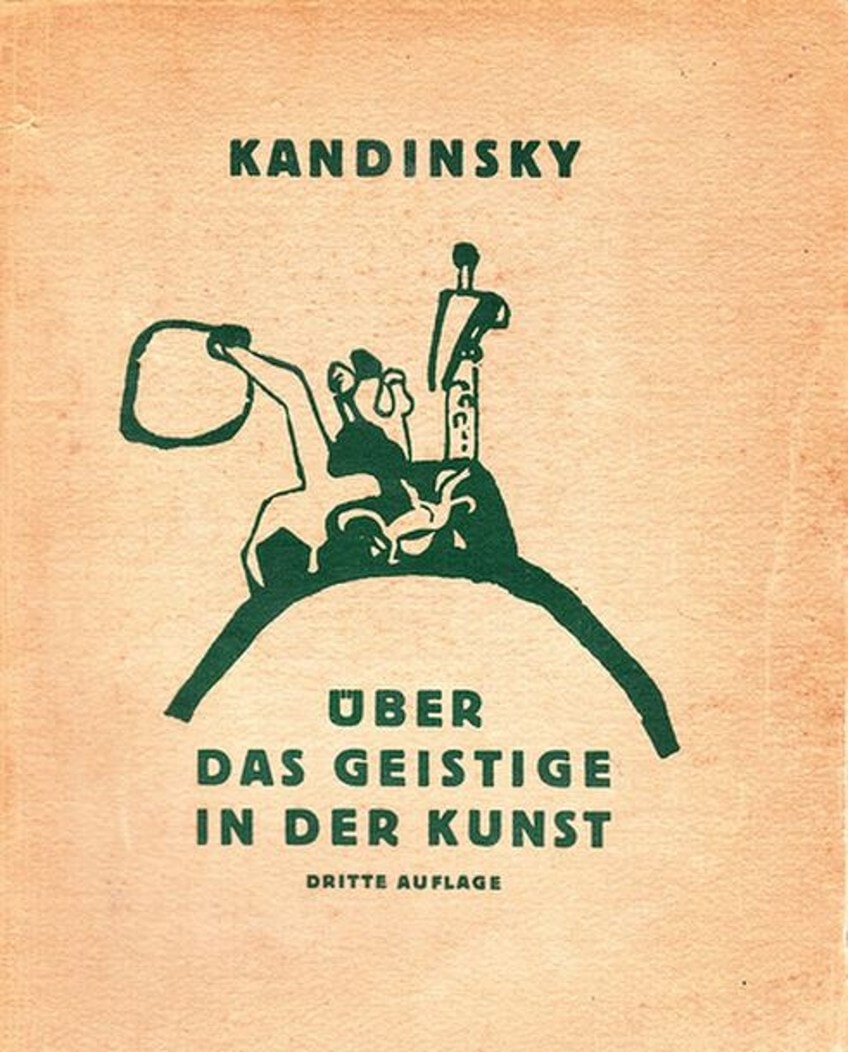

His writings in The Blue Rider Almanac and the thesis “On the Spiritual in Art” (1910) were both defense and advocacy of abstract art, as well as a statement that all artistic mediums were similarly competent at attaining a degree of spirituality. He felt that color may be employed in an artwork as a separate entity from the visible depiction of an item or other shape. These concepts had an almost instantaneous international influence, especially in the English-speaking community.

Michael Sadleir of the London-based Art News assessed his piece in 1912. When Sadleir released an English version of Kandinsky’s write-up in 1914, interest in him skyrocketed.

That year, excerpts from the text were published in the magazine Blast and the weekly artistic daily The New Age. However, Kandinsky had gained some attention in Britain previously; in 1910, he took part in the Allied Artists’ Exhibit (organized by Frank Rutter) at the Royal Albert Hall. Sadleir’s enthusiasm in Kandinsky also resulted in the acquisition of many wood-prints and the abstract work Fragment for Composition VII by the elder Michael Sadleir, in 1913, after a trip by the father and son to see Kandinsky that year in Munich. Between 1913 and 1923, these paintings were shown at Leeds, either at the university or at the Leeds Arts Club.

The Russian Abstract Artist’s Return to Russia

Kandinsky discovered Nina Andreevskaya in 1916 and married her on the 11th of February, 1917. Kandinsky was interested in Russian cultural politics and worked on art instruction and institution reform from 1918 until 1921. During this period, he produced little but dedicated his time to creative training, with a curriculum centered on form and color study; he also assisted to establish Moscow’s Institute of Artistic Culture. His mystical, evocative concept of art was eventually condemned by the Institute’s extreme adherents as being too personal and materialistic.

Kandinsky was summoned to Germany in 1921 by its creator, architect Walter Gropius, to join the Bauhaus of Weimar.

Return to Germany and the Bauhaus

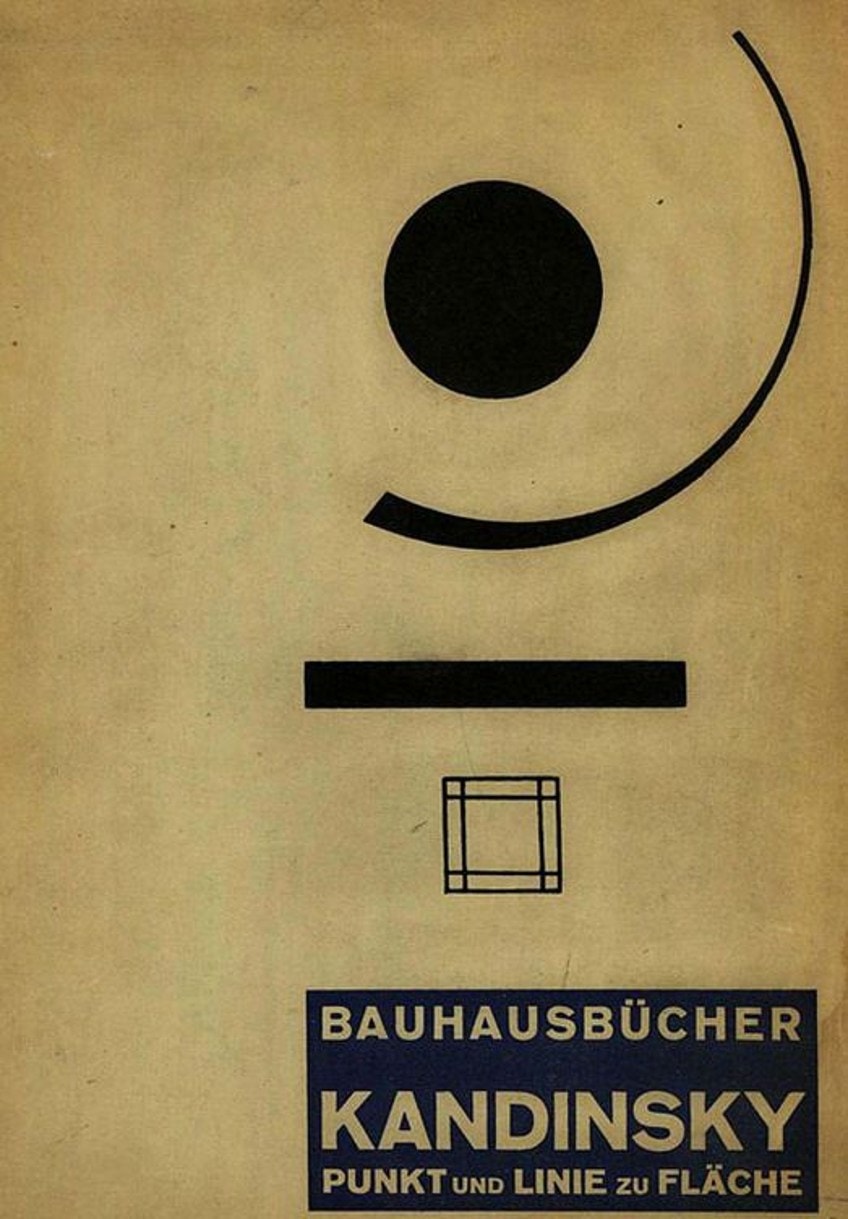

Kandinsky taught a complete beginner designing course and an intensive theoretical class at the Bauhaus, as well as painting workshops and a seminar in which he supplemented his color theory with new components of form psychoanalytic theory. In 1926, his second conceptual book (Point and Line to Plane) was published as a result of the advancement of his works on forms studies, notably on point and line formations.

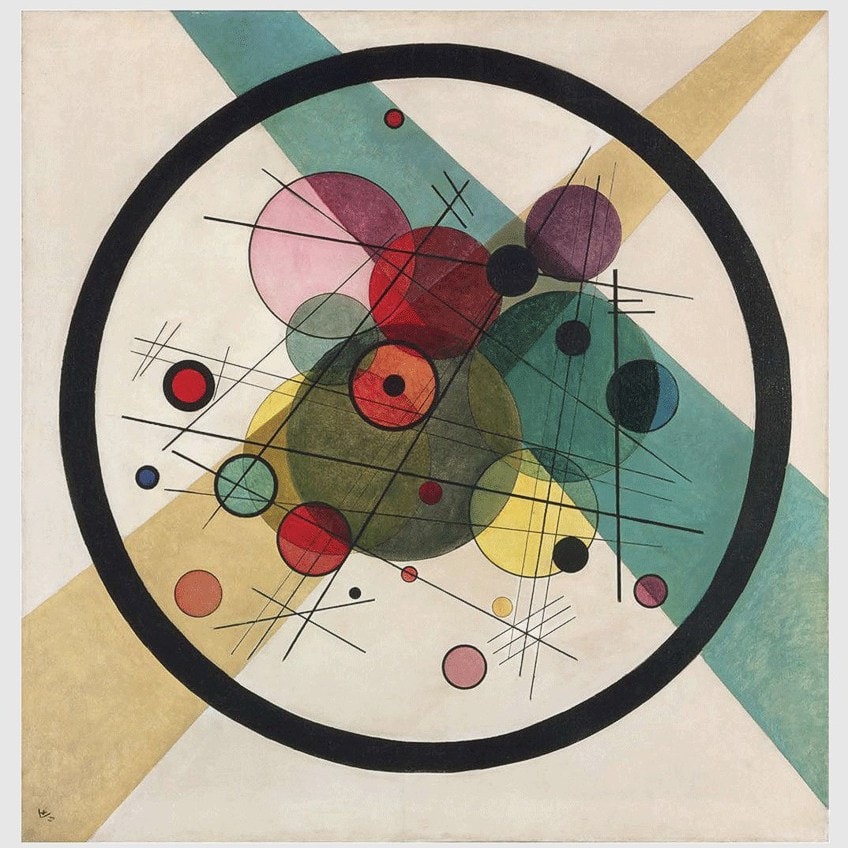

His investigations into the effects of pressures on straight lines, which resulted in the opposing tones of curving and slanted lines, corresponded with the work of Gestalt psychologists, whose research was also debated at the Bauhaus. Geometrical features, notably the circle, semi-circle, angles, straight lines, and bends, were increasingly important in his instruction and paintings.

This was a really fruitful time.

This flexibility is exemplified in his works by the handling of planes rich in colors and gradients, such as Yellow-red-blue (1925), in which Kandinsky demonstrates his independence from the prominent suprematism and constructivism trends of the period. Yellow-red-blue (1925) is a two-meter-wide work with numerous primary elements: a slanted red cross, a yellow rectangle, and a big bleak blue sphere; a plethora of sharp black lines, arcs, monochrome rings, and dispersed, colorful checker-boards add to its sensitive sophistication.

This basic visual recognition of shapes and the main hued masses current on the painting is only a first strategy to the inner world of the piece whose admiration requires deeper assertion, not only of the shapes and colors implicated in the artwork, but also their interaction, position in relation to each other on the canvas, as well as their overall harmony.

Greater Synthesis

Kandinsky developed his work in a living-room studio while living in a Paris flat. In his works, biomorphic shapes with fluid, non-geometric edges appear—figures that resemble life forms yet reveal the creator’s inner existence. Kandinsky employed unique color combinations that evoked Slavic popular art. He also sometimes blended sand with pigment to give his works a grainy, rustic feel.

This phase refers to a synthesis of Kandinsky’s prior work, in which he utilized and enriched all components.

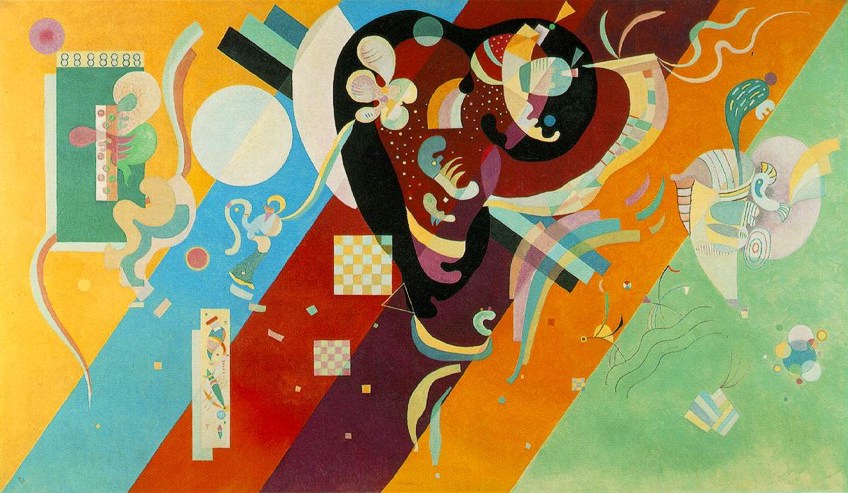

In 1936 and 1939, he completed his final two large works, enormous paintings that he had not created in many years. Composition IX (1936) has strongly contrasted, forceful diagonals, with the main form resembling a fetus in the womb.

Star pieces or little squares of color and colored bands stand out against the black backdrop of Composition X (1939), while cryptic hieroglyphs with hues cover a massive maroon bulk that appears to hover in the upper-left corner of the painting. Some traits are clear in Kandinsky’s artwork, while others are more subtle and hidden; they present themselves only gradually to individuals who have a deeper relationship with his work.

His shapes (which he gently harmonized and positioned) were meant to connect with the observer’s spirit.

Kandinsky the Painter’s Unique Art Style

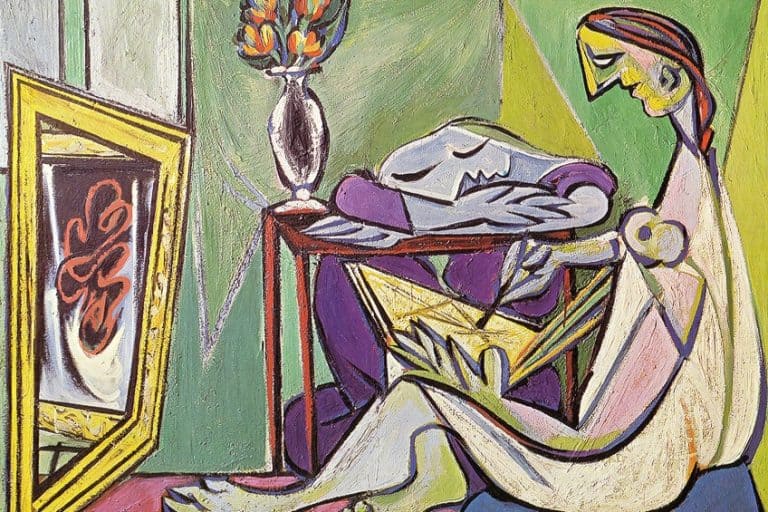

Wassily Kandinsky’s art combines music and mysticism. Kandinsky’s paintings in his early years exhibit a distinct expressionism approach, owing to his enthusiasm for contemporary music and tactile inclination. However, he accepted all creative trends of his period and forebears, such as Art Nouveau, Fauvism and the Blue Rider, Surrealism, and the Bauhaus, only to evolve closer to abstractionism as he studied spirituality in the artwork.

His object-free canvases depict spiritual abstraction evoked by music and feelings via a unity of sense. His works contain the uncertainty of form depicted in a range of colors as well as opposition against traditional aesthetic norms of the art world, motivated by his Christian faith and the internal requirement of an individual. This can be seen in his early works such as Improvision 10 (1910) and Composition IV (1911).

Over the duration of his creative career, his trademark or distinctive style can be further characterized and separated into three classifications: impulsive emotional responses, representational elements, and ultimate artworks. Kandinsky’s artworks got more vivid and emotive as he moved away from his early Impressionist influence, with sharper outlines and distinct linear features.

But ultimately, Kandinsky rejected graphical depiction with more multisensory billowing typhoons of colors and patterns, eliminating conventional examples to complexity and laying-bare different abstract forms.

What stayed constant, however, was his divine undertakings of representations and citations to Christianity. Kandinsky’s later paintings are also notable for their emotional coherence. He proved the uniformity of forms in his works, opening the path for even further abstraction, with different scales and vivid hues harmonized by a precise contrast of proportions and colors. Wassily Kandinsky frequently employed black in his works to emphasize the effect of vividly colored shapes, and his shapes were frequently biomorphic techniques to introduce surrealism into his work such as Last Watercolor (1944).

The Conception of Kandinsky’s Artworks

Kandinsky began the first seven of his 10 compositions, writing that “music is the supreme instructor.” The first three are only preserved in black-and-white images by another painter and colleague Gabriele Münter. While there are studies, drawings, and riffs especially of Composition II (1910), Kandinsky’s first three Compositions were confiscated during a Nazi raid on the Bauhaus in the 1930s. They were shown in the State-sponsored exhibition “Degenerate Art” before being burned.

Captivated by Christian prophecy and the concept of a New Age, doomsday is a frequent topic throughout Kandinsky’s first seven Creations.

Kandinsky painted works in the years leading up to World War I depicting an impending apocalypse that would transform personal and societal reality, as he wrote of the “artist as oracle” in his book Concerning the Spiritual in Art (1912). Kandinsky pulled from biblical legends such as Christ’s resurrection, Noah’s Ark, Jonah, and the whale, the four horsemen of the Apocalypse, Russian myths and legends, and the common mythical sensations of death and resurrection.

Never seeking to visualize any of these tales as a story, he utilized their shrouded symbolism as emblems of the motifs of destruction and death that he perceived were impending in the pre-World War I environment.

Kandinsky believed that a real artist who creates art out of “internal need” lives at the top of an upward pyramid, as he expressed in his writings. This ascending pyramid is piercing and moving forward. At the pinnacle of the pyramid, the contemporary artist stands alone, producing fresh breakthroughs and heralding tomorrow’s realities. Kandinsky was cognizant of scientific advances as well as the contributions of modern artists to fundamentally new ways of viewing and expressing the environment.

Composition IV (1911) and artworks that followed are mainly concentrated on eliciting a spiritual awakening in both the spectator and the artist. Kandinsky, like in his picture of the doomsday by water such as Composition VI (1913), puts the observer in the situation of encountering these epic narratives by interpreting them into modern terms with a feeling of desperation, urgency, and confusion).

Within the confines of language and visuals, this spiritual connection of spectator and artwork may be articulated. Kandinsky also described the connection between artist and audience as being open to both the senses and the thinking, as seen by his Der Blaue Reiter Almanac writings and hypothesizing with musician Arnold Schoenberg. Kandinsky theorized that (for illustration), yellow is the color of middle C on a brassy horn; black is the color of finality and the end of everything; and that color combination generates resonances, similar to notes performed on a piano.

Kandinsky began learning to play the keyboard and cello in 1871.

Kandinsky also established a philosophy of geometric shapes and their connections, suggesting that the sphere is the calmest form and embodies the human spirit, for instance. Kandinsky’s iconic setting for Mussorgsky’s “Pictures at an Exhibition” exemplifies his synaesthetic notion of a global correlation of shapes, hues, and musical notes. Wassily Kandinsky produced the stage version of “Pictures at an Exhibition” in Dessau in 1928. The original drawings of the stage components were recreated using current video technology and synced with the soundtrack in 2015, based on Kandinsky’s preparation papers and Felix Klee’s director’s screenplay.

Kandinsky was engaged on his Composition VI (1913) in another session with Münter during the Bavarian abstract art years. He had meant the piece, which had taken nearly six months of research and planning, to conjure a deluge, baptism, devastation, and regeneration all at the same time.

He grew stuck after sketching the piece on mural-sized wooden panels and was unable to continue. Münter informed him that he was stuck in his head and couldn’t get to the real subject of the photograph. She advised him to merely say the phrase deluge and concentrate on the tone rather than the content.

Kandinsky created and finished the mammoth piece in three days, reciting this term like a mantra.

Kandinsky Exhibitions

The Lenbachhaus gallery in Munich holds the largest collection of Kandinsky’s paintings in Europe and some of the most notable Kandinsky Exhibitions to date are as follows:

- Kandinsky, a significant exhibition of Kandinsky’s art, was shown at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum from 2009 through 2010. A collection of Kandinsky’s art was on display at the Guggenheim in 2017, titled Visionaries: Creating a Modern Guggenheim.

- From the 11th of June through the 4th of September, 2011, the Phillips Collection in Washington, D.C. had an exhibition titled Kandinsky and the Harmony of Silence, which included Painting with White Border and its preliminary studies.

- Vasily Kandinsky: Around the Circle will be on display at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum from the 8th of October, 2021 until the 5th of September, 2022, in tandem with a sequence of solo exhibits highlighting the works of modern artists Annie C. Jones, Etel Adnan, and Cecilia Vicuna.

Notable Artworks

Kandinsky’s artworks were influenced heavily by music. The pieces were often named using musical themes. Here are some of the artist’s most famous pieces.

- Small Worlds (1922)

- On White II (1923)

- Circles in a Circle (1923)

- Soft Hard (1926)

- Brown with Supplement (1935)

- Composition IX (1936)

- Composition X (1939)

- Circle and Square (1943)

Further Reading

Wassily Kandinsky was a Russian abstract artist who led an interesting life. If you would like to learn more about Wassily Kandinsky’s biography and artwork, then look no further. We have compiled a list of great reading recommendations in case you would like to explore this artist even further.

Concerning the Spiritual in Art (Kindle version 2012) by Wassily Kandinsky

This book is one of the most important texts in the history of contemporary art since it was a pioneering work in the drive to liberate art from its conventional links to practical reality. It was written by the famed nonobjective artist Wassily Kandinsky and describes Kandinsky’s own philosophy of painting as well as crystallizing concepts that influenced many other contemporary painters of the time.

This publication, along with his own ground-breaking works, had a significant effect on the evolution of contemporary art.

The first section, titled “About Aesthetic,” calls for a metaphysical transformation in art, allowing artists to portray their inner lives in ethereal, non-material terms. Painters should never have to rely on the physical universe for creative art, just as musicians do not rely on the material world for their songs. Kandinsky examines the neurology of colors and the vocabulary of form in the second section, “About Painting.”

- One of the most important documents in the history of modern art

- Written by the famous nonobjective painter Wassily Kandinsky

- A stimulating and necessary reading experience for every art lover

Point and Line to Plane (Kindle Edition 2012) by Wassily Kandinsky

Kandinsky gives a comprehensive explication of the fundamental dynamics of non-objective painting in this publication, one of the most significant books in 20th-century art. He discusses the notion of point as the “proto-element” of paintings, the function of point in the environment, song, and other arts, and the union of point and line that resulted in a distinct visual vocabulary using his own nomenclature.

He then delves into an engrossing examination of line, including the effect of power on line, lyric and dramatic aspects, and the conversion of many events into forms of linear representation.

Kandinsky shows out the natural connection of the components of paint, commenting on the role of textures, the component of time, and the link of all these aspects to the fundamental material plane called upon to accept the substance of a piece of artwork, with great creative insight.

- One of the most influential books in 20th-century art

- A detailed exposition of the inner dynamics of non-objective painting

- Illustrates the importance of Kandinsky's effect on 20th-century art

And that concludes our look at Kandinsky the artist. Wassily Kandinsky, a Russian abstract artist, popularized abstract painting in the 19th century and early 20th centuries. In his unique perspective on the form and function of art, Kandinsky the artist emphasized the merging of the visual and auditory. Noises were regarded as colors by him, and this unusual viewpoint inspired the production of Kandinsky’s artworks. Kandinsky, the painter, thought that the purpose of art was to convey the artist’s originality and inner vision, which required the elevation of objective truth. Kandinsky’s paintings aimed to show that total abstraction allowed for deeper, sublime perception and that copying nature inhibited this quest.

Read also our wassily kandinsky art web story.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is an Example of Wassily Kandinsky’s Portrait Paintings?

Wassily Kandinsky the painter was not known for making portrait paintings. Kandinsky’s art was known for being abstract. However, one portrait painting by Wassily Kandinsky is that of Gabriele Munter (1905).

What Kind of Art Did Wassily Kandinsky Make?

Kandinsky’s paintings were examples of abstract art. He was very influenced by music. Many of his paintings were representational of how he experienced music and art in a synergistic manner.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Wassily Kandinsky – A Portrait of Kandinsky the Artist.” Art in Context. December 29, 2021. URL: https://artincontext.org/wassily-kandinsky/

Meyer, I. (2021, 29 December). Wassily Kandinsky – A Portrait of Kandinsky the Artist. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/wassily-kandinsky/

Meyer, Isabella. “Wassily Kandinsky – A Portrait of Kandinsky the Artist.” Art in Context, December 29, 2021. https://artincontext.org/wassily-kandinsky/.