Mark Rothko – An Overview of Rothko’s Abstract Expressionism Period

Mark Rothko’s artworks evolved through several creative genres before settling on his characteristic 1950s pattern of soft, rectangular figures drifting on a tainted canvas of color. The Abstract Expressionism paintings by Rothko were filled with depth and bursting with ideas while being heavily inspired by philosophy and mythology. Rothko’s art was profoundly loaded with emotional meaning that he conveyed via a spectrum of forms that moved from figurative to abstract and was heavily influenced by Greek mythology, Nietzsche, and his Russian-Jewish origin.

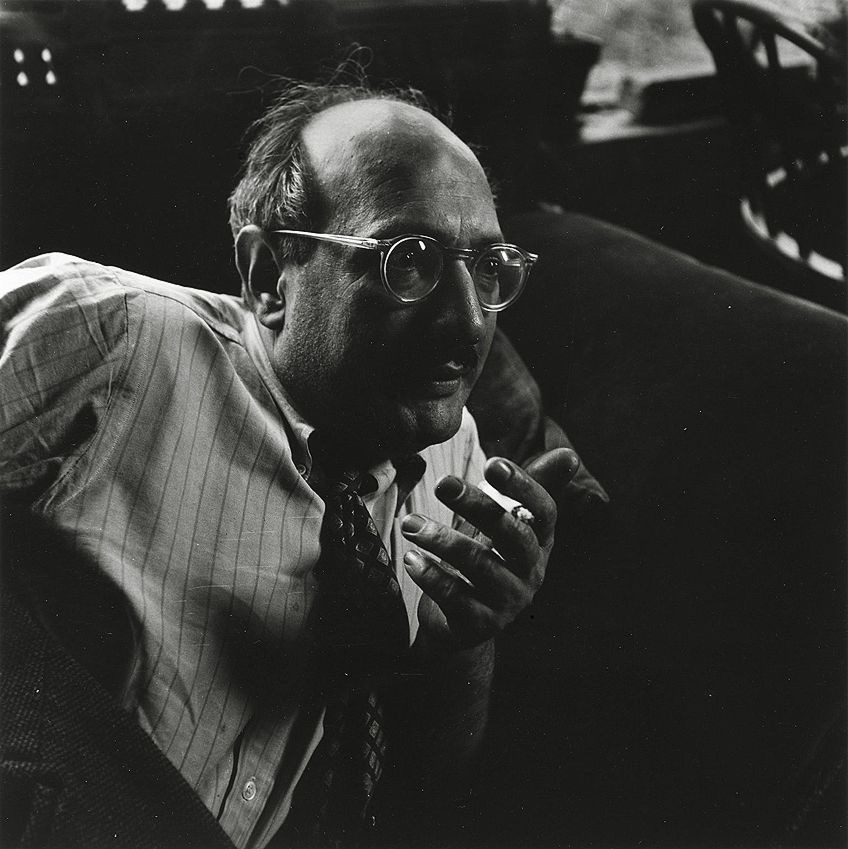

Mark Rothko’s Biography

| Nationality | American |

| Date of Birth | 25 September 1903 |

| Date of Death | 25 February 1970 |

| Place of Birth | Dvinsk, Russia |

Early Mark Rothko works, which included landscapes, still lifes, character analyses, and portraiture displayed a talent for combining Expressionism with Surrealism. His pursuit of new ways to express himself led to the creation of his Color Field pieces, which used iridescent color to create a feeling of spirituality. Mark Rothko’s social revolutionary views from his childhood remained with him throughout his life.

Specifically, he advocated for artists’ complete free speech, which he saw was undermined by the market. This belief frequently placed him in conflict with the art industry establishment, prompting him to reply publicly to criticism and, on occasion, deny contracts, sales, and exhibits.

Childhood

Marcus Rothkovich was born to Jacob and Anna Rothkovich in Dvinsk, Latvia. Due to the Russians’ constant hostility towards Zionist Jews, Mark’s father and his two older sons immigrated to the United States in 1910, accompanied by the remainder of his household in 1913. They landed in Portland, Oregon, but Jacob died only a few months after they arrived, forcing them to work in their new nation even though they only understood Hebrew and Russian.

Rothko was forced to learn English and work when he was quite young, leaving him with a sour taste in his mouth for his lost youth.

He graduated from Lincoln High School early because he was more interested in music than visual art. He was offered a scholarship at Yale University, but he soon discovered that the environment there was traditional and restrictive, and he dropped out without graduating in 1923.

Early Training

After leaving Yale, Rothko moved to New York City “to bum around and starve a little,” as he put it. Over the following few years, he worked odd jobs while attending Max Weber’s figure drawing and still life workshops at the Art Students League, which served as his sole creative education.

Rothko’s early works were primarily portraits, nudists, and urban settings.

On a subsequent journey to Portland, Rothko was selected to appear in a 1928 group show at the Opportunity Gallery alongside Milton Avery and Lou Harris. This was a huge accomplishment for a young foreigner who had left college and had only started painting three years before.

Mature Period

The impacts of the Great Recession were being experienced throughout American culture by the mid-1930s, and Rothko became obsessed with the political and social ramifications of mass unemployment. This prompted him to attend socialist Artists’ Union meetings. Among other things, he and many other designers lobbied for a municipal gallery in this city, which was finally granted.

Functioning in the Works Progress Administration’s Easel Division, Rothko met numerous other artists, but he felt most comfortable with a circle of other Russian Jewish artists. This ensemble, which included Joseph Solman, Adolph Gottlieb, and John Graham, exhibited at the Gallery Secession in 1934 and then became recognized as “The Ten.” “The Ten: Whitney Dissenters” debuted at the Mercury Galleries in 1936, barely three days after the Whitney display against which they were objecting.

In the 1930s, his work, influenced by Expressionism, was characterized by claustrophobic, urban themes depicted in frequently acidic hues such as “Entrance to Subway” (1938). In the 1940s, however, he became influenced by Surrealism and renounced Expressionism in favor of more abstract imagery that fused humanoid, vegetable, and creature forms. These he compared to archaic emblems, which he believed might communicate the emotions contained in old narratives.

Rothko started to regard humanity as engaged in a legendary battle with his personal will and nature. In 1939, he took a temporary break from painting to study mythology and philosophy, finding special significance in Nietzsche’s Birth of Tragedy. He got obsessed with the expression of inside emotion rather than representational similarity.

During this period, Rothko’s private life was overshadowed by his acute despair and, most likely, an undetected bipolar condition. He married jewelry designer Edith Sachar in 1932 but separated from her in 1945 to remarry again with Mary Alice Beistel, with whom he had two daughters. While Rothko is sometimes classed with Still and Newman as one of the three primary inspirers of Color Field painting, his works had several sudden and clearly defined style alterations.

The turning point came in the late 1940s when he began making prototype versions for his most popular works. His “multi-forms” have subsequently come to be known: figures are absent totally, and the arrangements are dominated by many soft-edged chunks of color that appear to float in space.

Rothko sought to remove all boundaries between the creator, the artwork, and the viewer. He landed on a strategy that employed the shimmering color to overwhelm the audience’s visual field. His paintings were intended to completely surround the spectator and lift them above and out of the mechanistic, commercial culture that artists like Rothko despised.

In 1949, Rothko drastically decreased the number of shapes in his paintings and expanded them to fill the canvas, floating above damaged color fields that are only discernible at their edges. These, his most well-known paintings, have come to be known as his “sectionals,” because Rothko thought they better matched his objective to create universal emblems of human need. Mark Rothko’s artworks, he asserted, were not self-expression, but rather pronouncements about the status of man.

Rothko would indeed continue working on the “sectionals” until his death. They are seen to be rather perplexing since their formal intent contradicts their meaning. Rothko himself remarked that his stylistic shifts were inspired by the increasing clarity of his content.

The all-over compositions, the softened borders, the continuity of color, and the fullness of form were all parts of Rothko’s evolution toward a mystical sense of the sublime, which was his objective. “The movement of an artist’s production will be toward clarity as it moves in space from point to point,” he declared, “toward the eradication of all obstructions between the artist and the concept, and between the vision and the viewer.”

Rothko received several distinctions during his career, including being appointed to represent the United States in 1958 at the Venice Biennale. However, praise never seemed to soothe Rothko’s troubled soul, and he became renowned as a harsh and belligerent figure. He refused an award from the Guggenheim Foundation as an opposition against the notion that art should be aggressive.

He was always self-assured and straightforward about his opinions: “I am not even an Abstractionist,” he once declared. He refrained from categorizing his works as “non-objective color-filled paintings.” Rather, he emphasized that these paintings by Rothko were inspired by human emotions such as “tragedy, joy, and dread.” He maintained that art was understood in respect of human existence rather than the impression of formal ties. He also disputed being a colorist, regardless of the fact that color was important to his work.

Rothko was known for standing up for his principles, even if it came at a high cost. In a self-defeating act of vengeance, he turned down a 1953 Whitney offer to buy two of his canvases because he had “a strong caring attitude for the lives my works would lead out in the world.”

Another key effort that would lead to his unhappiness was the sequence of paintings he did in 1958 for the Seagram Building. Initially, he was drawn to the notion of putting his work into an architectural context because he admired Vasari’s and Michelangelo’s chapels.

He spent two years creating three collections of works for this structure, but was disappointed with the first two; then he felt upset with the thought that his paintings would be shown in the lavish Four Seasons restaurant. Rothko’s social convictions drove him to resign from the commission because he couldn’t reconcile his own image or his dignity as a painter with the extravagant surroundings.

Late Period

John and Dominique de Menil, famous Houston art collectors and benefactors, gave Rothko a substantial commission in 1964. He was put to the task of making massive artworks for a non-denominational church on the campus of St. Thomas Catholic University, where Dominique held the position of chair of the Art Department. He created 14 paintings while collaborating with a group of architects to create a quiet space with a dark palette. Ever since, the Rothko Chapel has played host to international assemblies of some of the planet’s most revered religious figures, notably the Dalai Lama.

In 1968, Rothko was hospitalized for a few weeks after suffering an aortic aneurysm. This near-death experience would haunt him for the duration of his life. He was frustrated that his art was not being treated with the respect and devotion he believed it merited.

He also started to fear that his art would not leave a significant legacy, which prompted him to begin on his final big series, Black on Grays (1970), which featured 25 paintings and signified a significant departure from his earlier work.

Work, however, did not lift his mood, and at the age of 66, Rothko committed suicide by antidepressants. On February 25, 1970, his aide, Oliver Steindecker, arrived at the studio to discover him on the floor of the restroom. Many of his acquaintances were not shocked about Rothko’s sudden and dramatic death, claiming that he had lost his drive and motivation.

Some speculated that like other troubled artists before him, Rothko had succumbed to the tormented artist’s process of self-annihilation.

Shortly after his death, three of his dearest associates were appointed as guardians of his assets, and they secretly handed custody of about 800 pieces to the Marlborough Gallery, which had handled Rothko for several years, for a pittance of their market value. Kate Rothko, Rothko’s daughter, brought the men and the gallery to trial in what became an infamously ugly and long legal battle.

During the protracted court struggle, the art world’s occasionally illegal and immoral actions were publicly revealed for the first time. The Rothko children eventually won the case and got half of the fortune.

The “Rothko case,” according to Time writer Robert Hughes, was largely responsible for what he dubbed the “death of Abstract Expressionism.”

Important Paintings by Rothko

Rothko also talked about his idea in a communal psyche, grounded in antiquity and mythology. Stories, he argued, probed the basics of human experience: “If the names of my paintings evoke well-known myths from antiquity. I selected them because they are the timeless symbols on which we must rely to express fundamental psychological concepts. They are the emblems of man’s basic anxieties and drives, changing only in degree but never in essence, and contemporary psychology finds them enduring in our dreams, vernacular, and art, despite changes in the exterior conditions of life.”

Here are a few examples of the most important paintings by Rothko.

Crucifixion (1935)

| Date Completed | 1935 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 64 cm x 69 cm |

| Current Location | Location Unknown |

In November 1936, Rothko was one of several painters invited by Joseph Brummer to show at the Galerie Bonaparte in Paris; Crucifixion was one of the works presented. Rothko’s works, according to French critic Waldemar George, exhibited longing for 14th-century Italian art and exhibited “a genuine coloristic value.”

This work is contextually associated with Renaissance Christian art, but it also contains homages to “Lamentation of the Dead Christ” (1637) by Rembrandt.

The two crosses in the foreground, the third separated in the rear, and the figure clusters are all reminiscent of Rembrandt’s work of art. This piece is signed by Rothkowitz because he did not become Rothko until 1940.

Entrance to Subway (1938)

| Date Completed | 1938 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 118 cm x 86 cm |

| Current Location | Kate Rothko Prizel Collection |

Rothko’s fascination with current urban life is evident in this early figurative painting. The station’s architectural elements, including the ticket barriers and the “N” on the wall, are shakily recreated. Although the Impressionist influence softens the atmosphere of the photos, it represents many of the artist’s views about the modern metropolis.

New York City was supposed to be soulless and unnatural, and the faceless, scarcely drawn faces of the characters reflect part of that.

Oedipus (1944)

| Date Completed | 1944 |

| Medium | Oil on Linen |

| Dimensions | 21 cm x 13 cm |

| Current Location | Unknown |

In the early 1940s, Greek mythology was a major topic in Rothko’s artwork. Oedipus, who is claimed to have answered the Sphinx’s riddle, was both his father’s killer and his mother’s lover. His story has influenced both artists and psychologists.

For Rothko, he embodied the victims of ego and fury, which he saw as the source of man’s terrible character.

Rothko, like other figurative artists of the day, dissected and then recombined his figures in such a way that they created a single mass of human agglomeration. In this approach, Rothko hoped to convey how sorrow binds humanity together. The people appear to be gathered in an unusual nook of a strangely designed room.

The blue-green zigzag design appears in a number of his mythical paintings.

“If our names recall recognized stories of antiquity, we have utilized them again since they’re the timeless symbols on which we must fall back to communicate essential psychological notions,” Rothko remarked. “They express something genuine and existent in ourselves.”

Slow Swirl at the Edge of the Sea (1944)

| Date Completed | 1944 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 191 cm x 215 cm |

| Current Location | Museum of Modern Art |

This painting is an instance of Rothko’s Surrealist phase. Miro’s influence is most noticeable, notably in Miro’s The Family (1924). Rothko’s all-over composition of subdued hues, weird transparent forms, horizontal lines, curves, and swirls creates a dynamic yet veiled image of an unknown primeval world.

This charming image, painted while dating Mary Beistel, who then became his second wife, can alternatively be viewed as a romance inside a mythological and magical realm, with the figures enjoying the water as a rose-colored dawn breaks over the horizon.

No. 9 (1947)

| Date Completed | 1947 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 90 cm x 84 cm |

| Current Location | Dr. and Mrs. Jerome Dersh Collection |

In the spring of 1949, Rothko exhibited 11 artworks at Betty Parsons Gallery, one of which was No. 9. Leaving behind his earlier figures and landscapes, the “multiforms,” of which this is an example, comprised indistinct shapes produced from successive washes of paint.

The painting foreshadows Rothko’s 1949 breakthrough into so-called “sectionals.”

The warmer yellows, oranges, and reds of No. 9 are broken up by a strange black mass moving in from the left, as well as brushy bluish spirals in the bottom half. There are fuzzy borders, divided color blocks, and the beginnings of rectangular registers, as well as some size and scale experiments.

Rothko, on the other hand, saw these patterns as things endowed with his life force – lifeforms the drive for self-expression.

Four Darks in Red (1958)

| Date Completed | 1958 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 259 cm x 294 cm |

| Current Location | Whitney Museum of American Art |

In 1969, Rothko exhibited 11 paintings at the Sidney Janis Gallery, notably Four Darks in Red. The work exemplifies Rothko’s late-period fondness for browns and reds with its gloomy, restricted palette. It served as a model for the darker palette and horizontal arrangement that he would later employ in the Seagram Building works, which were never mounted.

Although the iconography of paintings like “Four Darks in Red” seemed to be far removed from that of his other works, Rothko thought that the rectangles only provided a new means of depicting the presences or spirits that he had attempted to capture in his previous works.

The Rothko Chapel (1965)

| Date Completed | 1965 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 60 x 52 |

| Current Location | Housten, TX |

The Rothko Chapel, on the campus of St. Thomas Catholic University, was financed by Dominique and John de Menil and contains 14 Rothko mural works. Three triptychs and five separate paintings are included.

All of these artworks are in an incredibly big size and are in dark maroon, purple, and black.

Rothko collaborated extensively with the architects, exerting nearly entire control over the design of the structure and its contemplative environment within. The pieces’ darkness might be seen as melancholy and evocative of Rothko’s mood in his final years.

Unfortunately, Rothko did not survive to see the Chapel’s official opening.

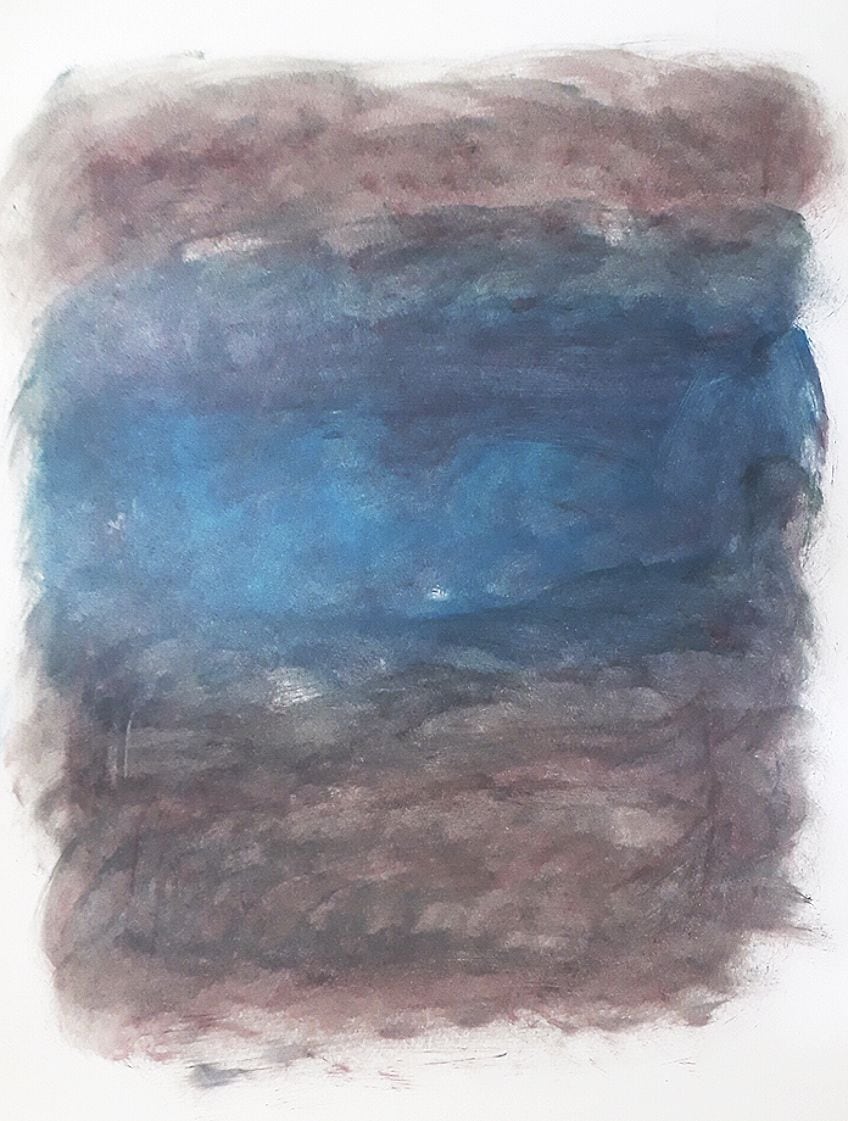

Untitled, Black on Gray (1969)

| Date Completed | 1969 |

| Medium | Acrylic on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 203 cm x 175 cm |

| Current Location | Estate of Mark Rothko |

Rothko invited many members of New York’s art community elites to his workshop to view his last series of paintings, the Black on Grays. While the incident was mostly veiled in secrecy, others speculated that these were foreshadowings of his death. Others assumed, based on the prominence of lunar pictures in popular culture, that they were renderings of moonscapes, while others assumed they were paintings of nighttime photography.

On average, they were not taken seriously, which was both heartbreaking and reassuring for Rothko, since he frequently thought that the internal worlds of his paintings were only comprehensible to him.

Because Rothko likes to “paint against,” the Black on Gray paintings were painted straight on a white canvas and without any underpainting. He produced in only two registers, reducing the colors and shrinking the painting to a more manageable and personal scale.

The stark contrast between light and dark produces grief that unfolds like a legendary and tragic psychological drama.

Legacy and Ideas of Mark Rothko

Painting absorbed Rothko’s life, and while he did not earn the recognition he believed his art merited during his lifetime, his popularity has grown considerably in the years after his death. Despite being at odds with the Abstract Expressionists’ more strictly rigorous painters, Rothko investigated the compositional power of color and shape on the human mind.

To be in the company of a Rothko is to be in the company of the pulsating vibrancy of his huge paintings; to experience, if only for a few moments, something of the magnificent spirituality he tirelessly attempted to inspire.

Nietzsche, mythology, and Jewish and political revolutionary ideas all had a significant impact on Rothko’s work and life. He previously told The New York Times that he would not justify his images because “they explain themselves.” Nonetheless, he was a vociferous supporter of artists, publishing several reviews as well as articles on the difficulties of the art industry.

Rothko composed the manuscript for The Artist’s Reality around 1941, most likely during his year-long break from painting. It was never published during his lifetime, instead, it languished in a manila folder labeled “miscellaneous files” for nearly 50 years.

These papers explore Rothko’s thoughts on Contemporary art, mythology, aesthetics, the essence of American art, and the difficulties of being a painter in his culture. The book is remarkable in that it never refers to Rothko’s personal work and instead talks from the perspective of the artist as a whole. While his political inclinations were unmistakably Leftist, he had a completely subjective attitude to theory. In The Artist’s Reality, Rothko emphasized the role of painters in society and how artists have changed creation myths into reality based on their own imaginative lives.

He highlighted how power, in its many incarnations, has established the norms that artists must follow, and how the market was the most recent tyrant of these rules. At the time of writing, WWII was breaking out in Europe, and fears about uniformity and dictatorship infused Rothko’s work with a continual sense of unease.

Above all, Rothko advocated for the artist’s independence. Rothko’s politics and poetry were inextricably linked, and his work is the best evidence of this. “I am still an anarchist!” he stated the year before he died.

Rothko, according to critic Dore Ashton, “could not sit nicely with the world,” and was continually looking for an escape. Many have viewed Rothko’s paintings in light of his suicide as portals through which he attempted to transcend a reality in which he could not find solace. Rothko claimed throughout his writings that his art was meant to be examined closely and personally, rather than from a secure, sterilized distance.

For individuals who find Rothko’s works intimidating, it may be reassuring to know that he meant to speak with his audience rather than frighten them. In 1951, he remarked, “I recognize that historically, the role of painting enormous works is something really grandiose and pretentious.” “However, the reason I paint them is exactly that I want to be personal and genuine.”

Most reviewers viewed Rothko’s artwork in formalist terms, which contradicted the artist’s goal to communicate epic spiritual drama. As a result, he may have had little sympathy for most professional commentators on his work.

He stated: “All art historians, specialists, and critics are people I despise and loathe. They are all parasites that feed on the body of a work of art. Their labor is not only ineffective but also deceptive. They have nothing to say about art or the painter that is worth listening to.”

Rosenberg stated in his New Yorker column “The Art World” in March 1978, “Rothko had condensed art to mass, tone, and color, with hue as the important ingredient.” Rothko’s “three or four horizontal bars of color” that he maintained for 20 years were “the content of his emotional existence. the exuberant tragic experience the single sourcebook of painting,” he stated.

Recommended Reading

We have introduced you to the early Mark Rothko artworks as well as Mark Rothko’s biography. Maybe you would like to learn more about Abstract Expressionism and paintings by Rothko. If so, you can find a list of his books right here.

The Artist’s Reality: Philosophies of Art (2006) by Mark Rothko

Mark Rothko, one of the 20th century’s most significant painters, created a unique and impassioned type of abstract art during his career. During his lifetime, Rothko also published several articles and critical reviews, lending his serious, intellectual, and outspoken voice to contemporary art disputes. Although the artist never published a book reflecting his various and nuanced ideas, his heirs claim that he periodically told friends and coworkers about the existence of such a manuscript.

- A classic text for years to come

- Offers insight into the work and the artistic philosophies of Rothko

- Discusses Rothko's ideas on being an artist in the modern art world

Mark Rothko: The Works on Canvas (1998) by David Anfam

This classic work, first published in 1998 and still in print, provides an overview of Mark Rothko’s remarkable corpus of works on canvas and panel. The collection includes the pictures for which Rothko is best known—large, mesmerizing, tragic fields of color—along with over 400 more paintings that are considerably less well known and depict an artist who was attentive to realism, abstract art, surrealism, and avant-garde concerns of his day. “By far the greatest monograph on Rothko ever published.”

- A quintessential volume that provides an overview of Rothko's career

- Includes both well-known and lesser-known artworks of Rothko

- Introduces the reader to almost 400 additional paintings by Rothko

Mark Rothko’s paintings progressed through numerous creative styles before arriving on his signature 1950s pattern of soft, rectangular shapes floating on a tainted canvas of color. Rothko’s Abstract Expressionism paintings were full of depth and ideas and were highly influenced by philosophy and mythology. Rothko’s art was profoundly weighted with an emotional meaning, which he portrayed via a spectrum of shapes ranging from figurative to abstract and greatly influenced by Greek mythology, Nietzsche, and his Russian-Jewish ancestry.

Take a look at our Mark Rothko paintings webstory here!

Frequently Asked Questions

Who Was Mark Rothko?

Early works by Mark Rothko, which comprised landscapes, still lifes, character analysis, and portraiture demonstrated a penchant for mixing Expressionism with Surrealism. His search for new methods to express himself resulted in the creation of his Hue Field sculptures, which utilized iridescent color to generate a spiritual sensation. Mark Rothko’s youthful social revolutionary beliefs stayed with him throughout his adulthood. He specifically pushed for artists’ entire freedom of expression, which he considered as being hampered by the market. This conviction regularly brought him into a confrontation with the art world elite, causing him to respond publicly to criticism and, on occasion, refuse contracts, sales, and displays.

What Was Mark Rothko Famous For?

Painting consumed Rothko’s life, and while he did not receive the acclaim he considered his paintings deserved during his lifetime, his renown has increased significantly in the years after his death. Despite his disagreements with the Abstract Expressionists’ more disciplined artists, Rothko examined the compositional power of color and shape on the human psyche. To be in the proximity of a Rothko is to be in the company of the pulsing vitality of his huge paintings; to encounter, if only for a few seconds, some of the beautiful spirituality he worked tirelessly to evoke.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Mark Rothko – An Overview of Rothko’s Abstract Expressionism Period.” Art in Context. March 5, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/mark-rothko/

Meyer, I. (2022, 5 March). Mark Rothko – An Overview of Rothko’s Abstract Expressionism Period. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/mark-rothko/

Meyer, Isabella. “Mark Rothko – An Overview of Rothko’s Abstract Expressionism Period.” Art in Context, March 5, 2022. https://artincontext.org/mark-rothko/.