Kazimir Malevich – Pioneering Suprematist Artist and Theorist

Kazimir Malevich was a prolific Russian avant-garde artist; he was not only a painter but also a writer. He formulated new art theories that would eventually become what he is still most known for, the art style Suprematism. Maybe a minimalist at heart, Malevich paved a way for non-objective art during a period of world history in the trenches. In this article, we explore Kazimir Malevich as a man and artist in more detail.

Artist in Context: Who Was Kazimir Malevich?

We will start by exploring Kazimir Malevich’s early life and where he was born. This will be followed by his education and artistic career, including mention of his early artistic influences and travels and how he became one of the famous Russian avant-garde artists in art history.

| Date of Birth | 23 February (Old Style calendar changes are dated for 11 February) 1879 |

| Date of Death | 15 May 1935 |

| Country of Birth | Born in or near Kyiv, Ukraine |

| Art Movements | Cubo-Futurism, Suprematism |

| Genre / Style | Abstract (Non-Objective) art |

| Mediums Used | Pencil, Painting (oils) |

| Dominant Themes | Geometric shapes, minimal and flat spaces |

The Birth and Early Life of Kazimir Malevich

Kazimir Severinovich Malevich was born in February 1879 in Kyiv, Ukraine; his name is originally spelled Kazimierz Malewicz. From Poland, his parents’ names were Ludwika and Seweryn Malewicz and there were reportedly 14 siblings comprising the family with nine that lived; Kazimir was the first-born. During Malevich’s life growing up, his family relocated on numerous occasions due to his father working, of which worked at a sugar factory at one stage.

It has also been written that Malevich started delving into the arts when he was 12 years old.

He also delved into peasant art styles because of his lifestyle on plantations compared to city life. However, although sources state he was not exposed to as much city culture or professional artists, it is clear he was exposed to some cultures growing up, which would have undoubtedly left an imprint on his imagination and artistic curiosities.

Education and Career

Malevich’s education spans numerous art schools and training. In 1895 he studied at the Kyiv School of Art, and it was around 1904, the same year his father died, that he started his studies in Moscow, where he moved to.

In Moscow, he trained in art at the Stroganov School of Art and at the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture, and Architecture, which was until around 1910. Some of the notable teachers in his life during this period included Fedor Ivanovich Rerberg.

During the 1900s, Malevich was exposed to a range of styles of art, notably Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, Art Nouveau, as well as Symbolism. He was also part of several artistic groups that explored Cubo-Futurism and Futurism as a style.

Some of the first groups Malevich joined and was invited to exhibit with were, namely, The Knave of Diamonds, also called The Jack of Diamonds, and then The Donkey’s Tail, which was started by members from the previously mentioned group who were more radical in their approaches.

One of the primary artists and founders of both groups included the Russian, Mikhail Fyodorovich Larionov, who was also known as pioneering Russian abstract art.

Additionally, he also gave both groups their names. His artistic style also moved around Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, Primitivism, and Cubo-Futurism. In around 1910, the Jack of Diamonds group held their first exhibition in Moscow, Kazimir Malevich joined and displayed. In 1912, Malevich also joined the first exhibition for The Donkey’s Tail, which is also noted where his Cubo-Futurist style developed.

Malevich did not remain with Larionov’s groups and reportedly joined the more Futurist artistic group called the Youth Union, otherwise Soyuz Molodyozhi. Malevich participated in several exhibitions along with other artists like Vladimir Tatlin, who was one of the founders of the Constructivism art movement in 1915.

The same Soyuz Molodyozhi group organized the Russian opera Victory Over the Sun (1913), of which Malevich was the stage set designer. This was also where he reportedly started his famous Black Square painting (1915), which was part of a curtain for the stage. He painted it in 1915, which became one of the most important abstract art pieces in Modern art history.

During 1914 Malevich also exhibited at the Paris Salon des Indépendants, collaborated as an illustrator for the publications by the Russian poet Velimir Khlebnikov, namely Selected Poems with Postscript, 1907 – 1914 and Roar! Gauntlets, 1908 – 1914.

He also produced lithographs that were in honor of Russia during World War I.

Malevich’s Manifesto: From Cubism and Futurism to Suprematism: The New Painterly Realism

During 1915 Malevich introduced new ideas to the world of art and the world at large; his ideas would mark him as one of the pioneering abstract artists, also termed non-representational, artists of our time, alongside other artists like Wassily Kandinsky and Piet Mondrian.

Malevich’s manifesto titled From Cubism and Futurism to Suprematism: The New Painterly Realism (1915) described a new type of art style removed from how art has been regarded, not only logically, but intuitively, it was called Suprematism. The artist started his ideas around 1913, the beginnings of which are evident in the artwork he produced for the Futurist opera Victory Over the Sun, including the Black Square painting previously mentioned.

What exactly was Suprematism about? It is important to remember that throughout his artistic career his style changed from Post-Impressionistic, Cubic, Futuristic, Primitivist, to Cubo-Futuristic, all of which developed into his new ideas of abstraction and the non-objective.

Suprematism was about going back to the fundamental forms of art, beyond reality. In his manifesto, he wrote about seeing the pure in art, once the “Madonnas and Venuses in pictures disappear”. He also wrote about how he transformed himself in the “zero of form” and out of academic art.

It was the reference to “zero” that held considerable significance in Malevich’s theories. He further wrote that he destroyed the “horizon-ring that has imprisoned the artist and the forms of nature”.

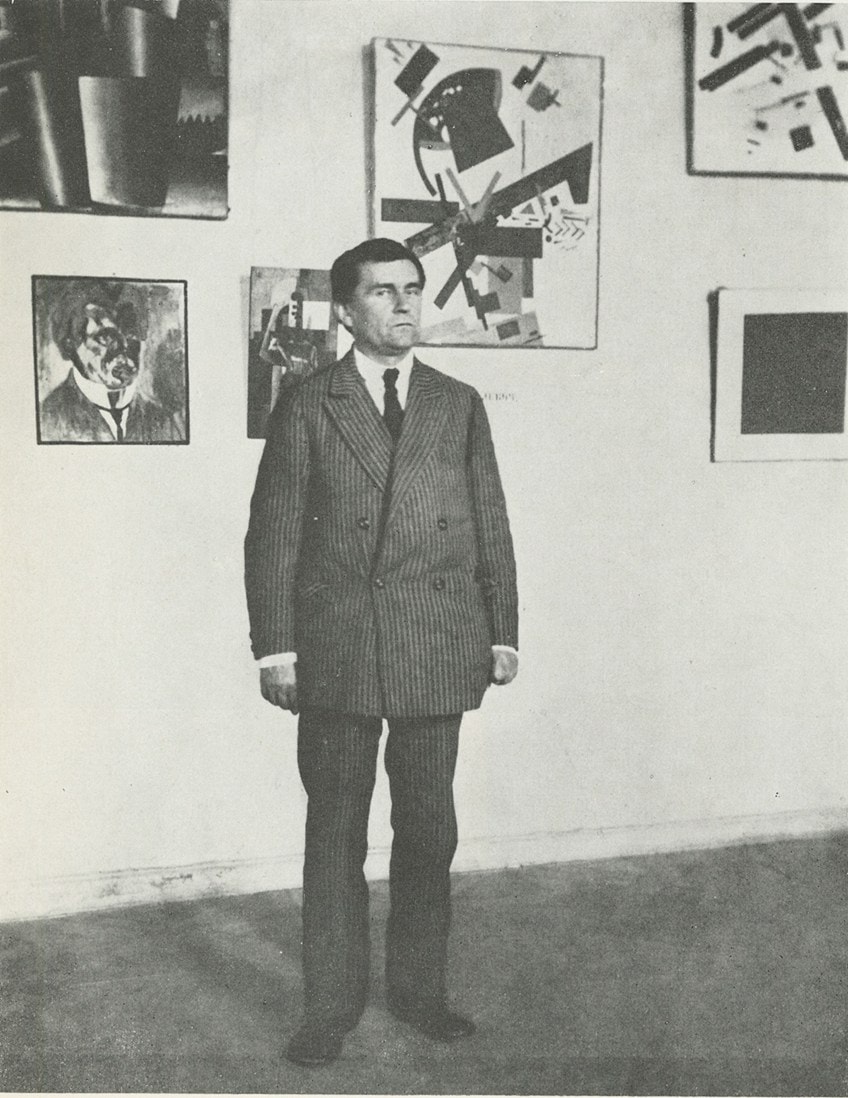

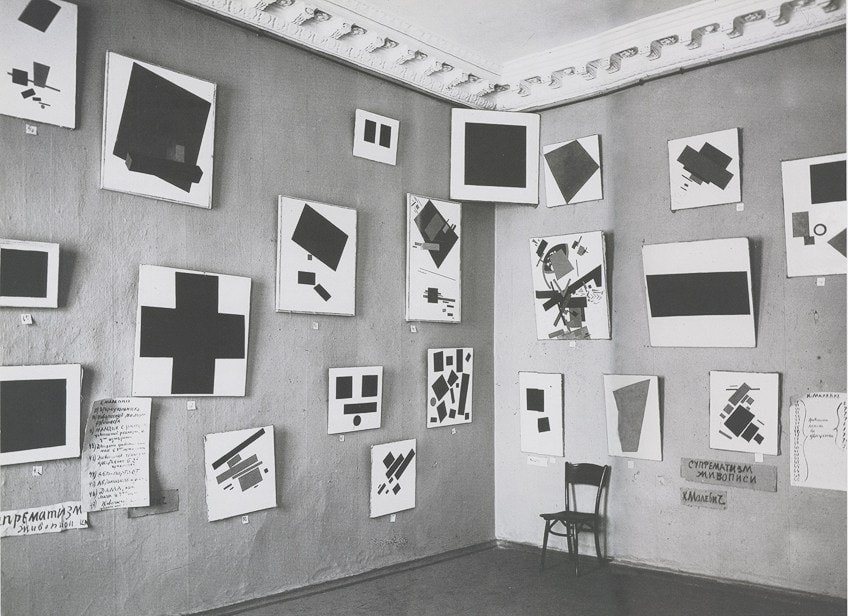

He believed in going back to the absolute fundamentality of form beyond the objective world, as he described it in his publication from 1927 The Non-Objective World, and into the world of feeling. The fundamental shapes he turned to were squares and circles. The exhibition called The Last Futurist Exhibition of Paintings 0,10 started on December 19, 1915, to January 17, 1916, in what was then Petrograd, now Saint Petersburg, at the Dobychina Art Bureau.

This marked the beginning of the Suprematism art movement and displayed reportedly 39 Malevich art pieces, and overall, there were apparently 155 artworks from other artists. The significance of the “0,10” lies in the zero, which referred to a new world, so to say, however, various sources state that the meaning of this is still unclear.

Pronounced as “zero-ten”, the ten could further denote Malevich’s belief in how “0” was beyond reality, referring to his writing about it and the “zero of form”, and so form goes beyond reality.

Additionally, many believe the “10” was included to denote the number of artists who were part of the exhibition, however, apparently there were 14 artists. Nevertheless, this exhibition and its name went together with the nature of the new Suprematism movement; this marked a turning point in Malevich’s artistic career.

There was also a journal titled Supremus, although the first edition was not published and the journal was not entirely successful, which was also partly due to the revolution in Russia and World War I. The word Suprematism originates from the word “superior”, which is rooted in the Latin supremus, meaning “highest” or “supreme”.

It was Malevich’s wish and belief through his endeavors that Suprematism would become the supreme form of art, so to say. He is often quoted as writing about explaining that it is the “supremacy of pure feeling or perception in the pictorial arts”.

Artistic Characteristics of Kazimir Malevich

If we look at the artistic characteristics of Kazimir Malevich’s art, we will look directly at the characteristics of his art movement called Suprematism, mentioned above. The primary characteristics comprising the Malevich paintings are fundamental geometric shapes like squares and circles in basic colors, and usually on a white background.

However, Malevich as an artist did not start with the level of abstraction in his art that we have come to expect from him. We will notice in his earlier paintings that his style ranged from Impressionist, Fauvist, Symbolist, as well as Cubist.

We could also say that Malevich’s art could be divided into his earlier figurative art that developed into a non-objective art style.

In his early works like Landscape with a Yellow House (Winter Landscape) (1906), there is the influence from Impressionism because of the areas of color denoting the composition, as well as giving the impression, so to say, of the Yellow House and its surroundings. His style consists of thick brushstrokes with brighter with bolder areas of color. It is more expressive in a way that is so different from his later artworks.

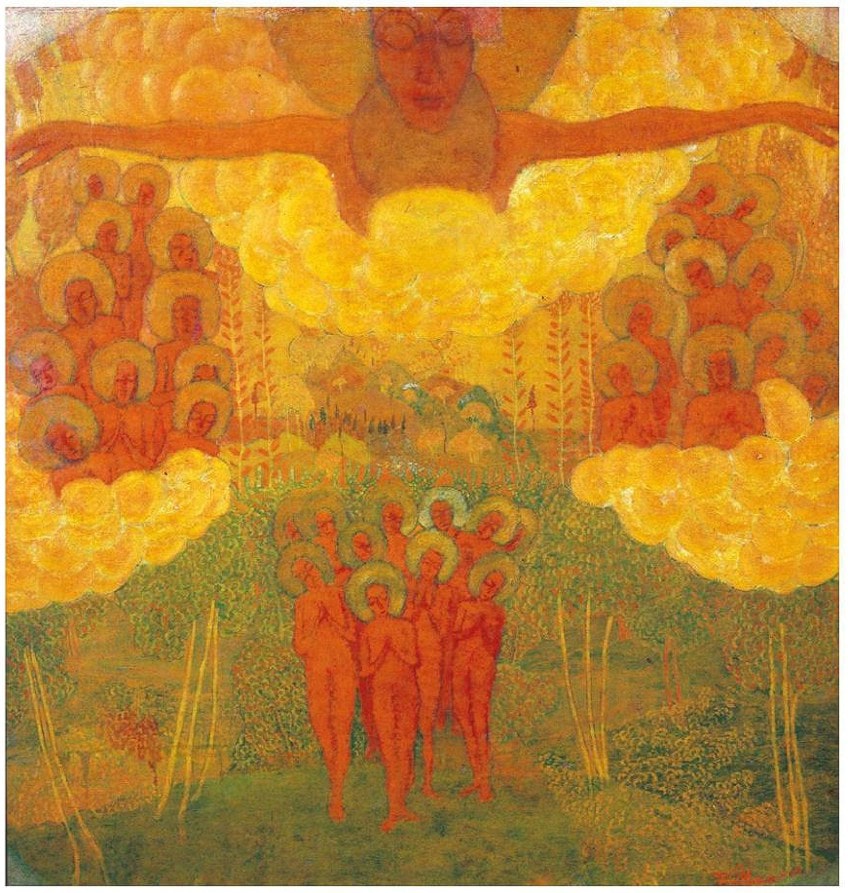

Another example from the earlier Malevich art collection is the Symbolist The Triumph of Heaven (1907), which depicts a religious scene composed of three groups of figures with halos over their heads and a large figure presiding over them with outstretched arms at the top of the painting.

The three groups of figures are standing with their hands by their chests in a prayer position. There are two groups on each side standing in clouds, while the group in the center stands on a grassy hill. The large overhead figure could possibly be symbolizing God, he too, is immersed in white balls of clouds.

This composition is reminiscent of icon paintings we would find from a Byzantine or Early Renaissance. Religious themes were important to Malevich and how he reportedly painted with the idea of peasant art in mind, which was a large part of his early life, including Eastern European folklore art.

Malevich explored the Cubism and Futurism art styles, which we will see in numerous of his paintings. The geometric motifs and stylization became dominant artistic characteristics, which he would continue to refine to simplicity in his Suprematism style.

Some Cubo-Futurist artworks include Woman at the Tram Stop (1913) and An Englishman in Moscow (1914). Both depict what is termed a deconstruction of the pictorial space. Although we can still understand certain motifs, which are figurative in nature, it hinges on abstract as the meaning of the figurations is also lost and simultaneously reconstructed.

The title of the painting tells us there is supposed to be a woman, however, we are not able to deduce the figure of a woman. We can notice images that appear like a calendar, photos of a bottle and a man, and many other different objects and shapes that could suggest the woman’s essence, but not the woman herself.

Malevich leaves it open-ended for the viewer.

Similarly, in An Englishman in Moscow Malevich placed various motifs to make a whole composition, ranging from the figurative with what appears to be a half image of a man, a church or mosque, a candle, a fish, a ladder, a pair of scissors, a spoon, and various letters in and numbers placed throughout the composition in what appears to be the Cyrillic script.

In another example, Reservist of the First Division (1914), Malevich utilizes not only oil paints, but real objects like a thermometer, postage stamps, and more. The artist created a collage of different motifs to convey the message of the composition on a more emotional level, beyond the “rational”. This also refers to the style, or technique, called zaum that Malevich adopted from the Futurist artists of Russia, he also reportedly termed it “zaum realism” along with other paintings.

Bordering on non-representational, Malevich’s paintings The Woodcutter (1912) and Woman with Pails: Dynamic Arrangement (1912-1913) depict that characteristic deconstruction of the figurative, while still being able to discern the figure presented.

Both above-mentioned paintings also depict the characteristic geometric shapes that Malevich utilized to convey the subject matter. We see in The Woodcutter, the male figure, a peasant, holds an ax in both hands, however, he is shaped by what are “cylindrical” and “conical” forms, reminiscent of the Cubism art style.

This painting has been described as having stylistic elements from Post-Impressionism, Cubism, as well as Symbolism regarding the theme of peasantry and folklore. This is an intersection of different characteristics, which we will also find in Woman with Pails: Dynamic Arrangement, although this composition appears more abstracted with a neutral color scheme. We can barely identify the woman here, however, there is evidence of her and the pails on both sides of her body. Again, Malevich introduces the geometric forms that are conical and cylindrical.

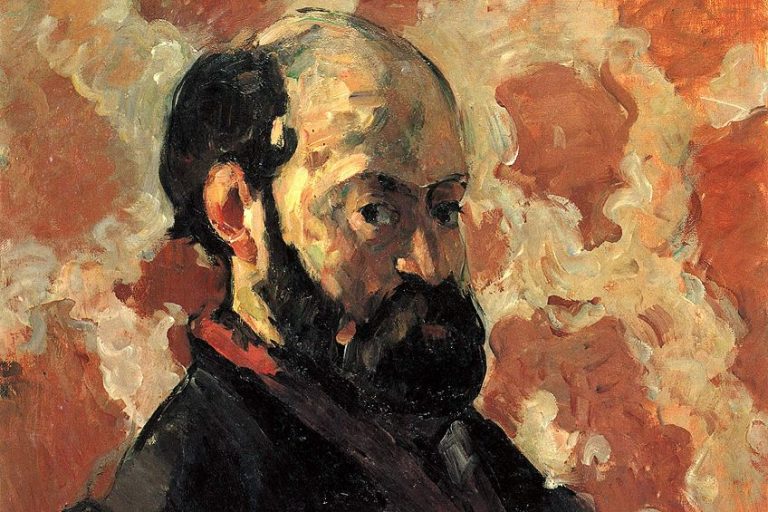

Malevich was believed to be inspired by the work of French Joseph Fernand Henri Léger as well as the stylistic theories from Paul Cézanne, both of which explored figuration through geometric shapes.

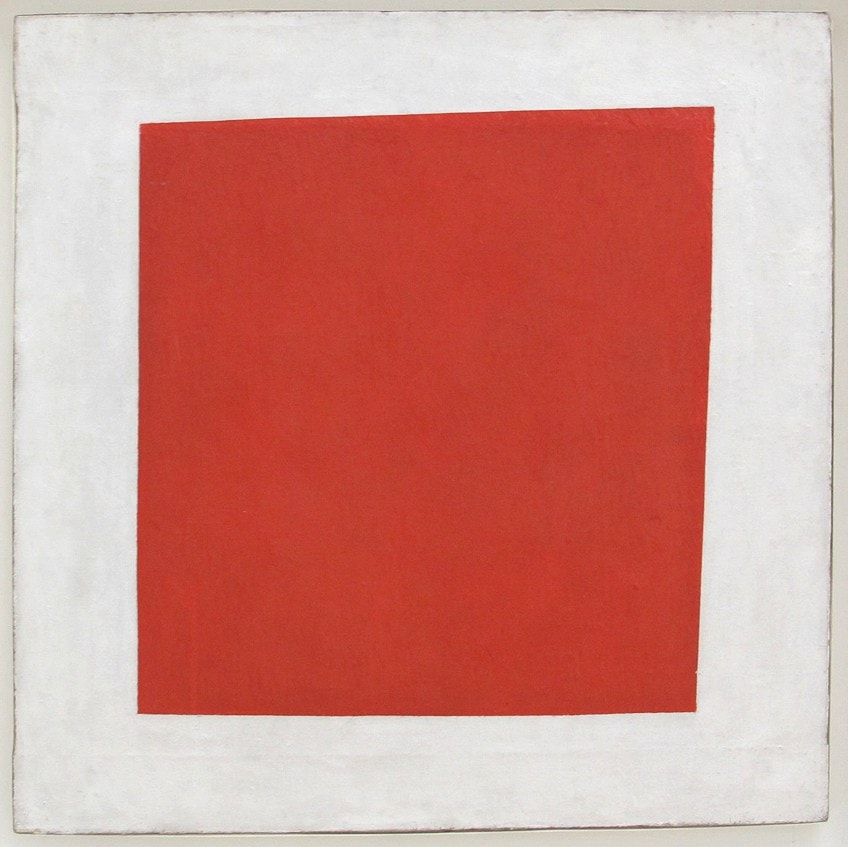

Malevich’s artistic characteristics started taking a turn into the non-figurative and wholly non-objective style. Examples include his Supremus No. 56 (1915-1916), Airplane Flying (1915), Black Square (1915), and a red square painting titled Painterly Realism of a Peasant Woman in Two Dimensions (Red Square) (1915), among others.

All the above-mentioned paintings by Malevich depict his Suprematist style, which was a simplified refinement of geometric shapes as well as color. There is also more focus on the square, rectangular, and linear shapes, especially in his famous Black Square and the similar Red Square (1915) paintings.

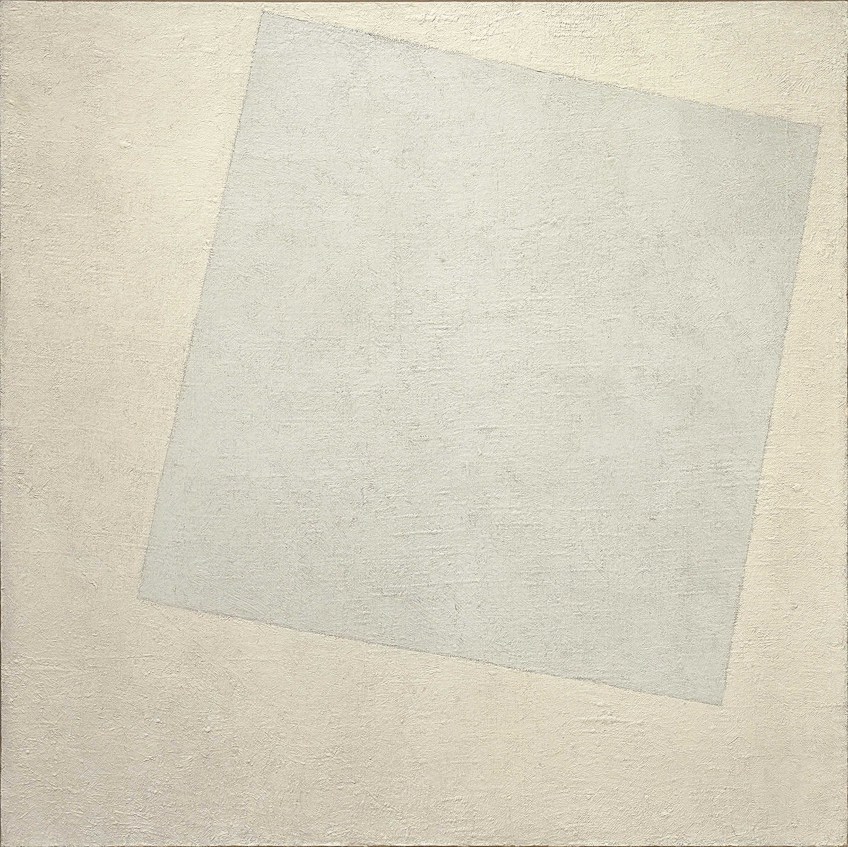

His White on White (1917-1918) painting is another example of one of the artist’s primary characteristics, so to say, which is depicting a space that seemingly moves beyond the reality we all know, a “new realism” as Malevich called it. In it, we see a white square over a white background.

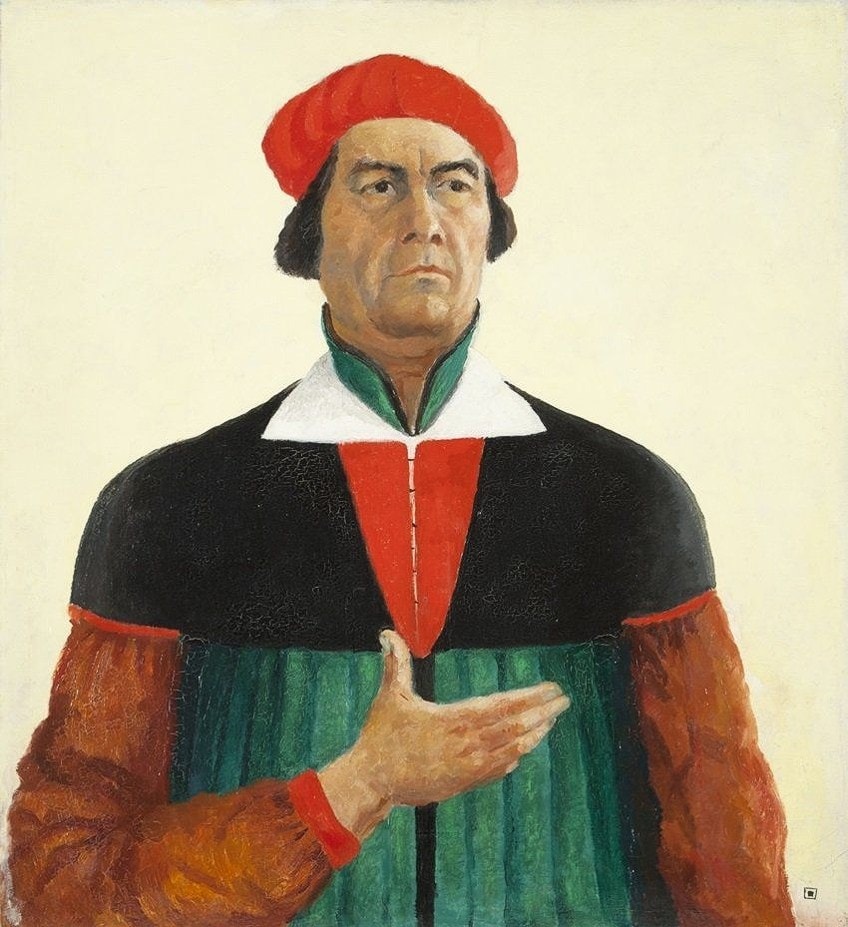

Malevich’s paintings changed in style during his later years, although he retained his belief in Suprematism, but ventured back into the figurative world of art, simultaneously exploring themes with peasants. We see this in examples like Two Peasant Figures (1928-1930), Sportsmen (1931), and his Self-Portrait (1933).

Important Exhibitions

Kazimir Malevich participated in numerous exhibitions throughout his life, below we will list several significant exhibitions including post-humous exhibitions. He participated in various earlier exhibitions mentioned above, namely through the artistic groups like The Jack of Diamonds (1910) and The Donkey’s Tail (1912), among others. Other retrospective exhibitions included the seminal Cubism and Abstract Art (1936) by Alfred H. Barr, Jr. at the Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) in New York City.

Additionally, in 1973, what was known as the first retrospective in the United States of the Malevich art collection, was held at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum.

The Last Futurist Exhibition of Paintings 0,10 (December 19, 1915, to January 17, 1916)

This was one of the first exhibitions that marked a turning point in Kazimir Malevich’s art career, intruding his new style called Suprematism. It was held in Petrograd, which is Saint Petersburg now in Russia, at the Dobychina Art Bureau.

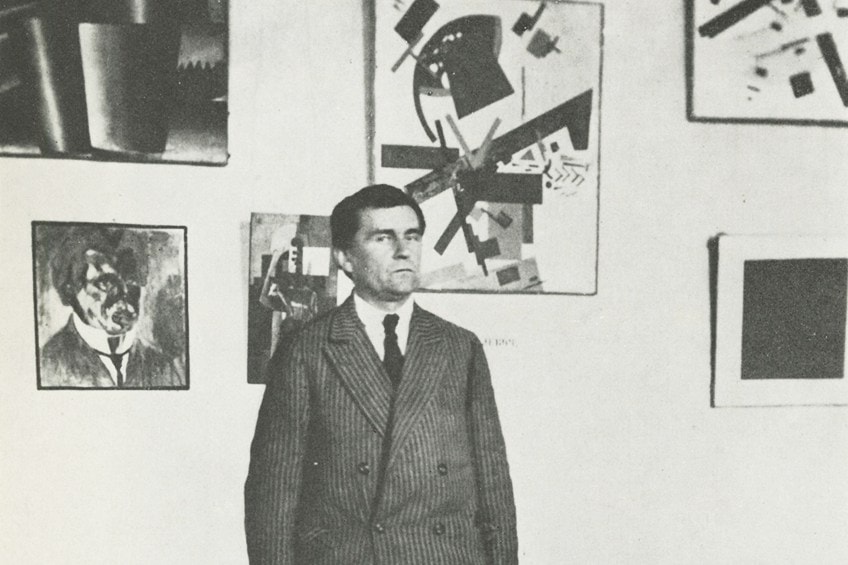

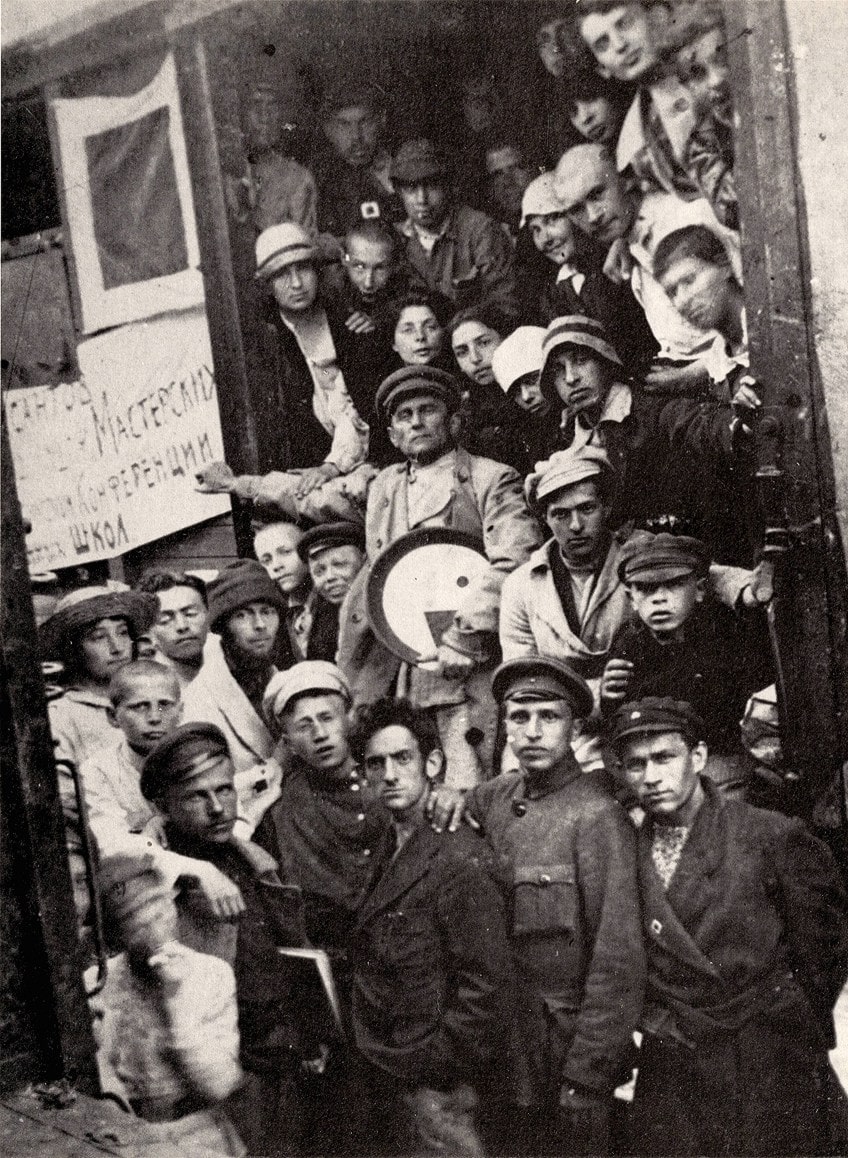

There were 155 artworks on display and there were around 14 artists who participated. Reportedly there were 39 Malevich paintings. We can view the exhibition space from what has been known as a single surviving black and white photograph, depicting various paintings next to the others, spaced out on two walls.

In the upper top corner just below the ceiling, is the Black Square painting placed not entirely flat on the wall’s surface, but bridging the gap between the two walls. All the paintings depict the characteristic geometric square, rectangular, and circular shapes in different sizes.

Some of the artists who exhibited alongside Malevich included Vladimir Tatlin, Nathan Altman Ksenia Boguslavskaya, Vasily Kamensky, Anna Mikhailovna Kirillova, Ivan Kliun, Mikhail Menkov, Vera Pestel, Liubov Popova, Ivan Puni, Olga Rozanova, Nadezhda Udaltsova, and Maria Ivanovna Vasilieva.

Malevich and the American Legacy (March 3 to April 30, 2011)

A posthumous exhibition from 2011 was Malevich and the American Legacy, held by the Gagosian Gallery in Madison Avenue, New York. It featured six Malevich paintings alongside the artworks of several contemporary American artists. The exhibition sought to bring the Russian avant-garde in closer proximity to America, as it has always been in Russia and not easily viewed.

Furthermore, the exhibition explored many facets of Malevich’s art and how it influenced others on display like Barnett Newman, Alexander Calder, Dan Flavin, Donald Judd, Carl Andre, Agnes Martin, and others.

From the exhibition’s description on its website, it is explained that it is “not only formal analogy that connects Malevich and American artists but also deeper aesthetic, conceptual, and spiritual correspondences. In dialogue with his work and ideas, later artists searched for elemental and universal forms consistent with simplified aesthetic aims”.

Kazimir Malevich Artworks

Below we provide a list of several of Kazimir Malevich’s paintings from his early years to his later years. This will include the title, date, dimensions, and media used for more detailed information about each painting. Many of the Malevich paintings are housed in different art museums throughout Russia and the United States at The Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) in New York City.

| Title | Date | Dimensions | Medium |

| The Knife Grinder | 1912 – 1913 | 79.5 x 79.5 centimeters | Oil on canvas |

| Morning in the Village After Snowstorm | 1912 – 1913 | 80 x 80 centimeters | Oil on canvas |

| Woman at a Poster Column | 1914 | 71 x 64 centimeters | Oil on canvas, collage, and lace |

| Reservist of the First Division | 1914 | 53.7 x 44.8 centimeters | Oil on canvas, collage, thermometer, paper, and postage stamp |

| Black Square | 1915 | 79.5 x 79.5 centimeters | Oil on linen |

| Painterly Realism of a Peasant Woman in Two Dimensions (Red Square) | 1915 | 53 x 53 centimeters | Oil on canvas |

| Painterly Realism of a Boy with a Knapsack. Color Masses in the Fourth Dimension | 1915 | 71.1 x 44.5 centimeters | Oil on canvas |

| Airplane Flying: Suprematist Composition | 1915 | 58.1 x 48.3 centimeters | Oil on canvas |

| Suprematist Composition: White On White | 1918 | 79.4 x 79.4 centimeters | Oil on canvas |

| Peasants | 1930 | 53 x 70 centimeters | Oil on canvas |

| Sportsmen | 1931 | Around 142 x 164 centimeters | Oil on canvas |

Book Recommendations

Below we provide a few book recommendations for further reading about Kazimir Malevich, his art theories, and his artworks. For any art enthusiast or art student, it is important to understand Malevich’s approach as he was one of the leading artists who pioneered abstract art. Furthermore, he was an important figure in the Russian avant-garde, proving essential reading for anyone researching Russian art.

Kazimir Malevich and the Russian Avant-Garde: Featuring Selections from the Khardziev and Costakis Collections (2014) by Linda Boersma and others.

This publication gives a thorough exploration of Kazimir Malevich’s art career and the different art styles he worked in like Impressionism, Fauvism, Symbolism, Cubism, and his later style, Suprematism. The artworks are from Nikolai Khardziev and Georges Costakis, who were prominent Russian avant-garde art collectors. Reviewers have written that this book has beautiful images of paintings, which would make it a worthwhile and versatile resource for art lovers and students.

- Tracing the breadth of Malevich's career through his various artworks

- All phases of the artist's development are represented here

- Contextualized alongside works by Malevich's contemporaries

Kasimir Malevich: The Non-Objective World: Bauhausbücher 11 (2021) by Walter Gropius (Editor), László Moholy-Nagy (Editor), and Kazimir Malevich

This is a copy or facsimile of Kazimir Malevich’s publication, also titled The Non-Objective World (1927), which he wrote when he started his new art style Suprematism. He wrote this after his first Manifesto in 1915. This was published by Lars Müller Publishers and their Bauhausbücher series. Malevich’s art style inspired the Bauhaus school of design, which provides the intersection of the two styles. Reviewers wrote that this book is worth buying and worth the read.

Malewicz: Beyond Censorship (2022) by Andréi Nakov

This book is written about Kazimir Malevich and his life, especially his earlier life and factors like his Polish history and interests in Russian religious art, as well as who he was an artist and leader of the Suprematism art theory and style. The author Andréi Nakov is an art historian and has written numerous other books and papers about Malevich and Russian avant-garde art in general.

- Critical study of the foundational myths about the artist's background

- An interrogation of anti-Modernist visual and cultural prejudices

Malevich Reigning Supreme

Kazimir Malevich was an artist during tumultuous times in the world’s history, not only did he live through the First World War, but also the Russian Revolution from 1917 until 1923. As a result of the strict political upheavals, Socialist Realism became the dominant mode of artistic expression.

With this, Malevich fought for his own self-expression, which was radically threatened by thwarting regimes. This also put a stopper to his seemingly overflowing non-objective art creativity. He was called anti-Soviet and barred from exhibiting his works or creating them. His artistic style somewhat changed to more acceptable subject matter during his later years.

Nonetheless, his artwork did make it to other parts of Europe and the United States, which opened the doors for other artists especially art styles like Minimalism to find their own modes of self-expression. Kazimir Malevich has continued to influence pop culture, from novels to films, even to the Winter Olympics in 2014, which was held in the Russian city of Sochi. He was and still is a notable figure in the art world, but more so, a godfather of the abstract, that which goes beyond form, into other dimensions and spaces where a “new realism” presides.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Was Kazimir Malevich’s Art Style?

Kazimir Malevich painted in different art styles, starting with influences from Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, Symbolism, Cubism, Futurism, which led to his style being primarily Cubo-Futuristic. He then developed his art theory and style named Suprematism, which became one of his most famous art styles and characterized him as an artist, as well as his art.

Who Painted the Black Square?

The Russian artist Kazimir Malevich painted the Black Square in 1915. This was the start of his art style called Suprematism, which also included similar geometric paintings like Red Square (1915) and White on White (1918).

What Did Kazimir Malevich Believe About Painting?

Kazimir Malevich sought to portray art devoid of subjectivity, he was a pioneer of non-objective art; a forefather of abstract art. Through his art theory and style called Suprematism, he believed in creating a so-called new realism through pure artistic feeling. His artworks were characterized by geometric shapes like squares.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Kazimir Malevich – Pioneering Suprematist Artist and Theorist.” Art in Context. March 10, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/kazimir-malevich/

Meyer, I. (2022, 10 March). Kazimir Malevich – Pioneering Suprematist Artist and Theorist. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/kazimir-malevich/

Meyer, Isabella. “Kazimir Malevich – Pioneering Suprematist Artist and Theorist.” Art in Context, March 10, 2022. https://artincontext.org/kazimir-malevich/.