Helen Frankenthaler – Discover the Color Field Queen

Helen Frankenthaler was an American artist with an extraordinary mastery of Abstraction. Her luminous, bold, and lyrical paintings are instantly recognizable and are a testament to her brave spirit and inquisitive nature. Helen Frankenthaler’s biography includes a long career spanning over 60 years, during which she developed an art style that was so unique that it transcended Abstract Expressionism and set her apart from all her peers.

Artist in Context: Who Was Helen Frankenthaler?

Helen Frankenthaler was a defining figure in American Abstract art during the mid-20th-century. She was friends with artists such as Jackson Pollock, Franz Kline, and Willem de Kooning; studied under Hans Hoffman, and was heavily influenced by Clement Greenberg.

Frankenthaler’s continuous explorations of new materials and techniques broadened the scope of painting on canvas, paper, and prints. Through her experimentation, she developed an innovative soak-stain painting technique, today known as Color Field Painting.

The following section unpacks Helen Frankenthaler’s biography in more depth.

| Date of Birth | 12 December 1928 |

| Date of Death | 27 December 2011 |

| Country of Birth | New York City, United States |

| Art Movements | Abstract Expressionism, Color Field Painting |

| Mediums Used | Painting, Printmaking |

Childhood and Early Education

Helen Frankenthaler was born the youngest of three girls into a wealthy Upper East Side family living in Manhattan. Her parents, Martha Lowenstein and Albert Frankenthaler, recognized her artistic potential from a young age and they stimulated her talents by sending her to progressive schools with strong art focuses. Her father was a supreme court judge for the state of New York and could afford to take his family on various trips during summer holidays. The settings of these trips were often immersed in nature and it is during these foundation years that Frankenthaler’s love for natural landscapes developed.

Her father sadly passed away from cancer when she was only 11 years old, and for four years after his death, she struggled with migraines and grief. Decades later, in 1954, Frankenthaler’s German mother, who was herself an unfulfilled artist and who suffered from Parkinson’s and depression, committed suicide at the age of 59 by jumping from a window.

As a young girl, she attended Dalton, a private co-educational school, where she studied under Rufino Tamayo, a Mexican colorist. At the age of 16, Frankenthaler knew that she would become an artist and she enrolled at Bennington College in Vermont, which was a women’s college at the time. Here, she explored Cubism and Abstract Expressionism under the leadership of Paul Feeley. Her use of color arrangements showed great promise from the start of her studies and only developed more as she matured her style.

Mature Period

Helen Frankenthaler moved back to New York in 1948, when she was 20 years old. After dabbling for a short while in art history at Columbia, she decided to become a full-time painter and rented a studio in downtown New York. Her work ethic and outgoing personality reflected a romantic sensibility of an artist’s life.

Her peers often criticized her flirtatious relationships, accusing her of careerism. This was compounded in 1950 when she met major art critic Clement Greenberg, who was 19 years her senior, and started a romantic relationship with him.

Their relationship would last for years, and Greenberg introduced her to prominent Abstract Expressionist artists, such as Jackson Pollock, Franz Kline, Lee Krasner, and Willem de Koning. He also arranged for Frankenthaler to study under Hans Hofmann, who greatly influenced her work.

A breakthrough came in Frankenthaler’s career in 1952 when she created arguably her most famous painting, Mountains and Sea. This painting introduced her groundbreaking soak-stain technique, which involved soaking raw, unprimed canvas in thinned oil paints. She worked on the floor, pouring luminous colors of thinned oil paint onto the canvas, and moving it around with sponges and window wipers. At times, she used charcoal to manipulate the shapes of pooled paint.

Helen Frankenthaler’s paintings never moved away from this method, yet her work was never repetitive. Years later, she described that this new painting method came about from a “combination of impatience, laziness, and innovation”.

Initially, Mountains and Sea had not gained immediate acclaim, as the Times described it as “sweet and unambitious”. A year later, however, Greenberg brought the painters Morris Louis and Kenneth Noland to Frankenthaler’s studio to see the painting. They were so excited about the work that they started to experiment with Frankenthaler’s soak-stain technique.

She developed a new style called “Color Field Painting”, or “Post-Painterly Abstraction”. Years later, Morris Louis would famously state that Frankenthaler’s work was the “bridge from Pollock to what was possible”.

Building on this early success, Helen Frankenthaler’s paintings continued to develop, becoming more daring and showcasing the essence of her love for natural landscapes. An important event, though some would argue ‘limiting’, happened in Frankenthaler’s life five years after painting Mountains and Sea. In 1957, she met and fell in love with Robert Motherwell, also an Abstract Expressionist painter. A year later the couple got married, and over their 13-year marriage, they would be mutual influences on each other’s work. At the time, Motherwell already had two daughters from his first marriage, and Frankenthaler embraced both fully. The newly forged family bought a townhouse in the Upper East Side, continuing the affluent lifestyle they both were accustomed to since childhood.

Partly because of their wealth, and partly because of their success, Frankenthaler and Motherwell were dubbed the “golden couple” by their peers.

In 1960, Frankenthaler had her first big solo show at the Jewish Museum of New York. The exhibition was a retrospective curated by Frank O’Hara, the famous poet. During this time, Frankenthaler started to use acrylic paints instead of oil. This shift allowed even more vibrancy in her work and can be seen in paintings like Canyon (1965). In 1966, she started to exhibit internationally, representing the United States Pavilion at the Venice Biennale. The following year she would also exhibit at the International and Universal Exposition in Montreal.

Frankenthaler and Motherwell divorced in 1971. After her divorce, she decided to travel, on two occasions, to the American Southwest. The desert landscape influenced the color palette of many of her future works and can perhaps most noticeably be seen in her 1976 work, Desert Pass.

Some critics would later argue that Frankenthaler’s work stagnated slightly during her marriage. This might be because, after the divorce, she seemed to increasingly experiment again with new materials and mediums, including printmaking. Initially, she was prone to lithography as the soft stone allowed her to create painterly marks like that in her paintings. Her experimentation with lithography led her to explore woodcuts, a medium she developed with great mastery.

Late Period

Helen Frankenthaler made art until the final years of her life. During the 1980s and 1990s, she continued to make paintings, woodcuts, and even sculptures in steel and clay. She also designed costumes and sets for theater productions, including for England’s Royal Ballet. In 1994, she got married again, this time to an investment banker. Five years into the marriage, they both moved to Connecticut, to a house next to the Long Island Sound.

This new location greatly influenced her work, with her new paintings reflecting the turquoise blue tones of the waters in the landscape.

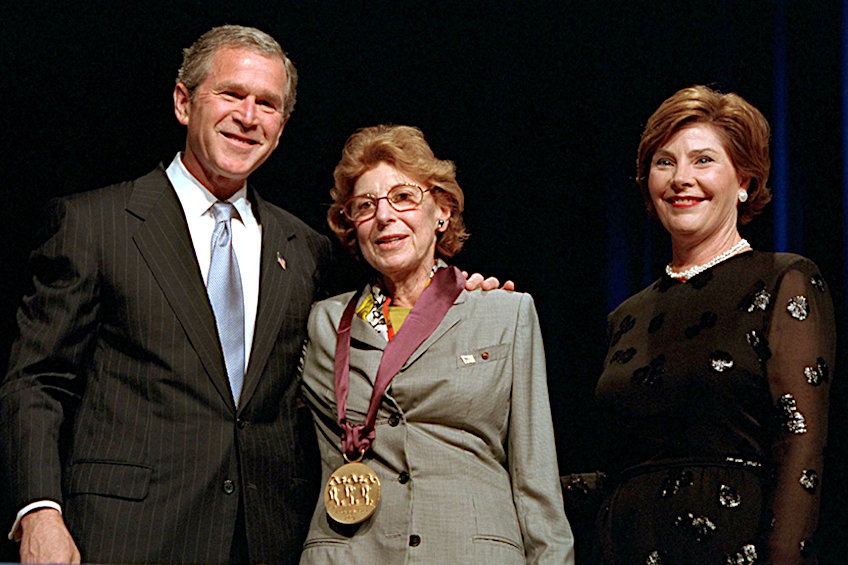

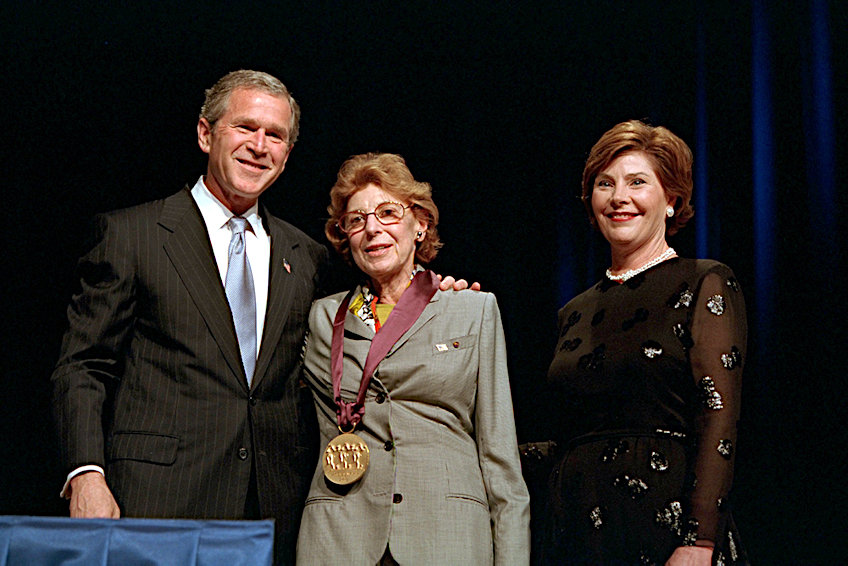

She lived the last dozen years of her life here and she passed away in the Connecticut home in 2011 at the age of 83. Before her passing, her work was honored at the Knoedler & Company gallery in New York in a retrospective titled Frankenthaler at Eighty: Six Decades. She was also a recipient of the National Medal of Arts in 2001.

Important Helen Frankenthaler Paintings and Woodcuts

Frankenthaler’s pioneering soak-stain technique gave rise to a new style of painting that influenced many prominent painters at the time and continues to inspire painters today. The flat, spare, and meditative quality of Color Field art is often described as the healing force of the often-anxious feeling Abstract Expressionist movement, and the precursor to Minimalism. Below, we analyze a selection of her most prominent works to illustrate the mastery of her art.

Mountains and Sea (1952)

| Artwork Title | Mountains and Sea |

| Date | 1952 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Size (cm) | 219.4 x 297.8 |

| Collection | Helen Frankenthaler Foundation (on extended loan to the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.) |

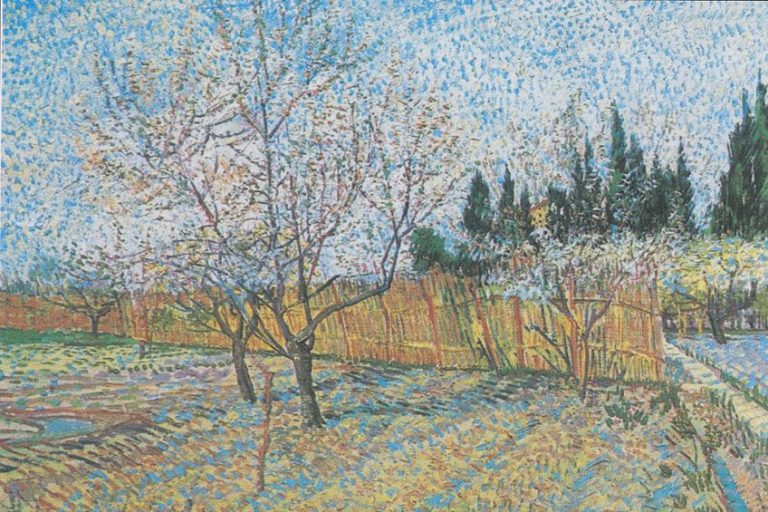

In Mountains and Sea, Frankenthaler’s early cubist and surrealist influence can be seen, but already her work carried a unique lyrical quality that became her signature to all her work. In fact, this painting became Frankenthaler’s landmark work, introducing her unique soak-stain process. Even though the work is monumental (approximately 2 x 3 meters), it remains quiet and intimate. Frankenthaler painted this work after she returned from a trip to Nova Scotia. She explained that the work is made from her memories of the Cape Breton environs, landscapes that deeply affected her.

Although the work is non-representational and thus does not literally refer to the Nova Scotia landscapes, there are elements of shape and color that recall the image of a kind of seascape meeting a landscape, where shapes of blue and green join. Mountains and Sea became the first work Frankenthaler would professionally exhibit.

Jacob’s Ladder (1957)

| Artwork Title | Jacob’s Ladder |

| Date | 1957 |

| Medium | Acrylic on canvas |

| Size (m) | 2.88 x 1.78 |

| Collection | Museum of Modern Art, New York |

A gorgeous painting filled with colorful shapes that is soft and almost blurry. Although the work shows very few brush strokes, it remains very gestural, and one can almost feel the movement of the artist as she made the work. The title of the work invited a Biblical reading of the work, which inspires the image of a ladder that descends from, or into, heaven. This ladder seems to be referenced in the work as there are two vertical lines near the center of the composition. At the top of the suggested ladder, the space seems to open, with less dense, soft arrangements of color shapes.

The translucent tone of the colors, created with Frankenthaler’s soak-stain technique, adds to the sublime, ephemeral quality of the painting. The shapes seem to resemble an arrangement of flowers, but as an abstract painting, the interpretation of the work will differ from viewer to viewer.

Orange Mood (1966)

| Artwork Title | Orange Mood |

| Date | 1966 |

| Medium | Acrylic on canvas |

| Size (cm) | 213.4 x 201.9 |

| Collection | Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; gift of Mrs. Elizabeth G. Weymouth |

During the 1950s and early 1960s, Frankenthaler’s work was repeatedly described as being extremely feminine, thanks to the soft shapes and colors that dominated her compositions. Some feminist movements even argued that the works reference menstrual blood stains. Frankenthaler, however, denied any such associations and asked that her work’s value should be derived only from the quality of the painting, regardless of her gender. It is perhaps because of such gendered readings of her work that Frankenthaler started to include bolder and brighter colors to her work.

Works like Orange Mood create strong statements, both in composition, color, and size. These are also the first works in which Frankenthaler swapped oil paint for acrylics, allowing for more richly saturated tones.

Essence Mulberry (1977)

| Artwork Title | Essence Mulberry |

| Date | 1977 |

| Medium | Woodcut Composition |

| Size (cm) | 101 x 47.3 |

| Collection | Museum of Modern Art, New York |

Perhaps one of Frankenthaler’s most well-known woodcuts is Essence Mulberry, a large blue-gray shape containing orange marking, encased by two broad stripes of bright red. The work is an eight-color woodcut that Frankenthaler made in collaboration with Kenneth Tyler’s printmaking studio in New Bedford, New York. This was the first print Frankenthaler would make in collaboration with the printmaking studio, called Tyler Graphics. She continued to collaborate with the studio for about 25 years.

The composition and color palate of the work is as daring as the materials used. Frankenthaler was apparently inspired to make the work after seeing mulberries growing in Ken Tyler’s studio in New York, and as such used mulberry juice in the making of the work as well.

The printmaking studio also attested to Frankenthaler’s use of tools to make the woodcuts, saying that “she used anything she could find” and that “the world became her toolbox”. Frankenthaler’s love for experimentation and her eclectic toolbox led to works like Essence Mulberry, which has both depth in its layers and character in its color.

Madame Butterfly (2000)

| Artwork Title | Madame Butterfly |

| Date | 2000 |

| Medium | Color woodcut on paper |

| Size (cm) | 106 x 201.9 |

| Collection | Helen Frankenthaler Collection |

Many argue that Frankenthaler’s greatest achievement is her woodcut print, Madame Butterfly (2000). The work is a monumental, extremely poetic print on paper that Frankenthaler made in collaboration with Tyler Graphics printmaking studio. This was the final and most technically challenging woodcut that Frankenthaler ever made with the studio. It consisted of 46 woodblocks and was printed with 102 colors.

To achieve the soft-looking surface of Madame Butterfly, Frankenthaler used yet another innovative technique, which she called “guzzying”. This technique involved distressing the surfaces of the wood, using sandpaper and dental floss. The result is a print on paper that captures the spontaneity and intensity, but also the delicate nature and fluidity, of Frankenthaler’s soak-stain paintings.

Book Recommendations

Frankenthaler was not only one of the most influential Abstract Expressionist artists of 20th century America, she was also an artist seen to transcend Abstract Expressionism by pioneering a whole new art style, Color Field Painting. The following books situate Frankenthaler within the larger American Abstraction landscape and give context to the revolutionary nature of her work.

Women of Abstract Expressionism (2016) by Irving Sandler, edited by Joan Marter

This book is a stunning full-color survey of women who contributed to Abstract Expressionism, including Helen Frankenthaler, Joan Mitchell, Jay DeFeo, Elaine de Kooning, and many more. This book offers insight into the lives and art of many previously underrepresented female artists who contributed to American Abstract Expressionism.

Ninth Street Women: Lee Krasner, Elaine de Kooning, Grace Hartigan, Joan Mitchell, and Helen Frankenthaler: Five Painters and the Movement That Changed Modern Art (2019) by Mary Gabriel

This book, which we also mentioned in our article about Joan Mitchell, features five female artists who revolutionized modern art. This book is sure to enthrall you since it was written by the National Book Award and Pulitzer Prize finalist, Mary Gabriel. The New York Times described the book as “gratifying, generous, and lush” as it unfolds the lives and art of five bold women.

Fierce Poise: Helen Frankenthaler and 1950s New York (2022) by Alexander Nemerov

You cannot go wrong by choosing this new publication for your next artist read. This Helen Frankenthaler biography was named one of Vogue’s Best Books of the Year and is a National Book Critics Circle Finalist. Nemerov, an acclaimed art historian, writes a stunning biography where he eloquently captures the moments in Frankenthaler’s life that defined her career. The writing style of this book is as lyrical and poetic as Frankenthaler’s work itself.

- Expert fusion of intimate biography with incisive art critique

- Focuses on the formative period of Frankenthaler's career

- Provides a compelling insight in the artist's life and work

Although Helen Frankenthaler’s paintings might seem, as she herself claimed, “born in a minute”, her work nonetheless is executed with meticulous attention to the balance between control and spontaneity. Perhaps the most impressive quality of her work is how incredibly ‘unpainted’ they seem, as almost no brushwork can be seen. As such, her work is steeped in material and color, with nothing on top and nothing beneath, the surface becomes the luminous work itself.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Art Style Did Helen Frankenthaler Use?

Broadly speaking, Frankenthaler could be classified as a Modernist. More specifically, she is a painter specialized in Abstraction. Initially, her work was described as Abstract Expressionist, but later, her work was seen to transcend this. Today, most people consider Frankenthaler’s art style to be either Post-painterly Abstraction, Lyrical Abstraction, or, simply, Color Field painting.

What Art Technique Did Helen Frankenthaler Use?

Frankenthaler is best known for her invention of the soak-stain painting technique. She started using this method of painting in the 1950s. The technique involves the thinning down of paints, which are usually thick and oily, to the consistency of watercolor. This thinned paint would then be used to soak the canvas with colors to create abstract compositions.

Who Did Helen Frankenthaler Influence?

The artists that Frankenthaler most directly influenced were Morris Louis and Kenneth Noland, who completely changed their style after seeing Frankenthaler’s Mountain and Sea painting. Another artist that Frankenthaler directly influenced was Cleve Gray. Frankenthaler continues to influence and inspire many artists today.

Chrisél Attewell (b. 1994) is a multidisciplinary artist from South Africa. Her work is research-driven and experimental. Inspired by current socio-ecological concerns, Attewell’s work explores the nuances in people’s connection to the Earth, to other species, and to each other. She works with various mediums, including installation, sculpture, photography, and painting, and prefers natural materials, such as hemp canvas, oil paint, glass, clay, and stone.

She received her BAFA (Fine Arts, Cum Laude) from the University of Pretoria in 2016 and is currently pursuing her MA in Visual Arts at the University of Johannesburg. Her work has been represented locally and internationally in numerous exhibitions, residencies, and art fairs. Attewell was selected as a Sasol New Signatures finalist (2016, 2017) and a Top 100 finalist for the ABSA L’Atelier (2018). Attewell was selected as a 2018 recipient of the Young Female Residency Award, founded by Benon Lutaaya.

Her work was showcased at the 2019 and 2022 Contemporary Istanbul with Berman Contemporary and her latest solo exhibition, titled Sociogenesis: Resilience under Fire, curated by Els van Mourik, was exhibited in 2020 at Berman Contemporary in Johannesburg. Attewell also exhibited at the main section of the 2022 Investec Cape Town Art Fair.

Learn more about Chrisél Attwell and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Chrisél, Attewell, “Helen Frankenthaler – Discover the Color Field Queen.” Art in Context. May 5, 2023. URL: https://artincontext.org/helen-frankenthaler/

Attewell, C. (2023, 5 May). Helen Frankenthaler – Discover the Color Field Queen. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/helen-frankenthaler/

Attewell, Chrisél. “Helen Frankenthaler – Discover the Color Field Queen.” Art in Context, May 5, 2023. https://artincontext.org/helen-frankenthaler/.