“Liberty Leading the People” by Eugène Delacroix – A Detailed Analysis

Liberty Leading the People (1830) by Eugène Delacroix is considered one of the most revolutionary paintings from French history and French Romanticism. It is described as a “national icon”, depicting and symbolizing the French uprising against the monarchy of the time it was painted. In this article, we will look at this painting in more detail.

Artist Abstract: Who Was Eugène Delacroix?

The leading French Romanticist Ferdinand Victor Eugène Delacroix was born on April 26, 1798, and died on August 13, 1863. He was born in Paris at Charenton Saint Maurice and studied at the Lycée Louis-le-Grand in 1815 under the tutelage of Pierre-Narcisse Guérin, which is where he also met the influential Théodore Géricault.

His artistic foundations lay in his studies of classical art and artists, making copies of their work in the Louvre. He was influenced by literature from Lord Byron and Shakespeare, among others, and explored watercolor painting. Delacroix painted subjects from modern life, and he was known to be rebellious in his attitude toward established rules. His style was more expressive.

He traveled to Morocco in 1832, which further influenced his art and subject matter, and his work influenced later artists from art styles like Impressionism.

Liberty Leading the People (1830) by Eugène Delacroix in Context

Below we will provide a Liberty Leading the People analysis, starting with a brief contextual outline discussing it as a French Romantic artwork and the historical events portrayed in this scene, as well as its political impact. This will be followed by a formal analysis where we take a closer look at the subject matter and Delacroix’s artistic style related to how he utilized color, brushwork, space, and more.

| Artist | Eugène Delacroix |

| Date Painted | 1830 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Genre | History painting |

| Period / Movement | Romanticism |

| Dimensions | 260 x 325 centimeters |

| Series / Versions | N/A |

| Where Is It Housed? | Louvre Museum, Paris |

| What It Is Worth | Purchased for 3,000 FF in 1831 |

Contextual Analysis: A Brief Socio-Historical Overview

In 1830, the July Revolution in France was known as the “Three Glorious Days”, in French, Les Trois Glorieuses, and it lasted, as the name indicates, for three days, namely, July 27, 28, and 29. This was a revolutionary moment in French history because it brought all the people together against the ruling king, who was King Charles X at the time.

Why was there an uprising against the monarchy? While this is a complex subject with numerous scholarly debates behind it, for the purposes of this article, we will provide a truncated explanation.

King Charles X was a conservative king, he was part of what was known as the political faction called the ultra-royalists who believed in the ruling of the monarchy and the Catholic church. He was also from the Bourbon family branch, which was reinstated in 1814, referred to as the Bourbon Restoration, after the rule of Emperor Napoleon.

Charles X was made king in 1824 after his brother King Louis XVIII died, he instilled new policies that caused uproars among the populace leading to his eventual overthrow, which resulted in the July Revolution of 1830. This was followed by a new king, King Louis-Philippe I, who was also known as the “Citizen King” and “King of the French”, he was from the Orléans family branch.

It is important to note when we look at Liberty Leading the People by Eugène Delacroix, that it is not a depiction of the events from the French Revolution, which occurred in 1789 and lasted until around 1799. The latter resulted in Napoleon Bonaparte’s rule, who also started the French Consulate and overthrew the monarchy and power of the Catholic church. Delacroix contributed to the revolution in his own way, supporting it through his painting.

He is often quoted in a letter to his brother, which he wrote in October 1830, stating, “I have undertaken a modern subject, a barricade, and although I may not have fought for my country, at least I shall have painted for her. It has restored my good spirits”.

A Revolutionary Time in Art: From Mental to Emotional

While it was a revolutionary time in France, it was as much so in the world of art. Romanticism was a burgeoning movement that started around the late 1700s until around the mid-1800s. It was not only in France, but had roots in England and Germany, and across other parts of Europe. Similarly, it was not only in the visual arts, but prominent in other genres like music, literature, and architecture.

The primary essence, so to say, of Romanticism was its revolt against the intellectualism from the Age of Enlightenment and the dominant Neoclassical art style of the time. It favored the expression of emotions as well as the value of nature over industrialization. Let us briefly explore Neoclassicism and more about Delacroix before we continue with the Liberty Leading the People analysis.

The Neoclassical art style was about rationality, reason, order, and the ideals held by Classical art from Greek and Rome. The French Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture, otherwise referred to in French as the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture, was in control of how art was created, also setting a hierarchy of the types of genres of painting.

History paintings were placed as the most important genre, which consisted of subject matter from history, for example, Biblical, Classical mythology, or ancient historical events. These paintings were often produced as large pieces.

Some of the proponents of Neoclassicism were Jacques-Louis David, who was influenced by the forerunners like the Baroque Nicolas Poussin. The latter created paintings based around line and form, which resulted in artworks that were rooted in mental faculties like order, balance, and symmetry, with subject matter delivering moral messages.

Jacques-Louis David’s pupil, Jean-Auguste-Dominiques Ingres became famous for his stance on the classical values that also centered around the utilization of line and form in paintings, but importantly also drawing. He was known as a Poussinist, which was a group of artists named after Nicolas Poussin.

The Poussinists and Rubenists were two rivaling and influential groups in art at the time.

Ingres was also reportedly one of Delacroix’s greatest rivals in art because Delacroix was a Rubenist, espousing the more emotive qualities of art like color. Rubenists drew inspiration from the Flemish artist Peter Paul Rubens, who was also a Baroque artist. He was known for his emotive painting style.

If we look at French Romanticism, Delacroix was a pioneering artist within this movement and created artworks that moved away from the more conventional Neoclassical paintings and rules of the French Academy.

Romanticism was a platform for the artist to explore modern subject matter, although still in the form of historical paintings.

Formal Analysis: A Brief Compositional Overview

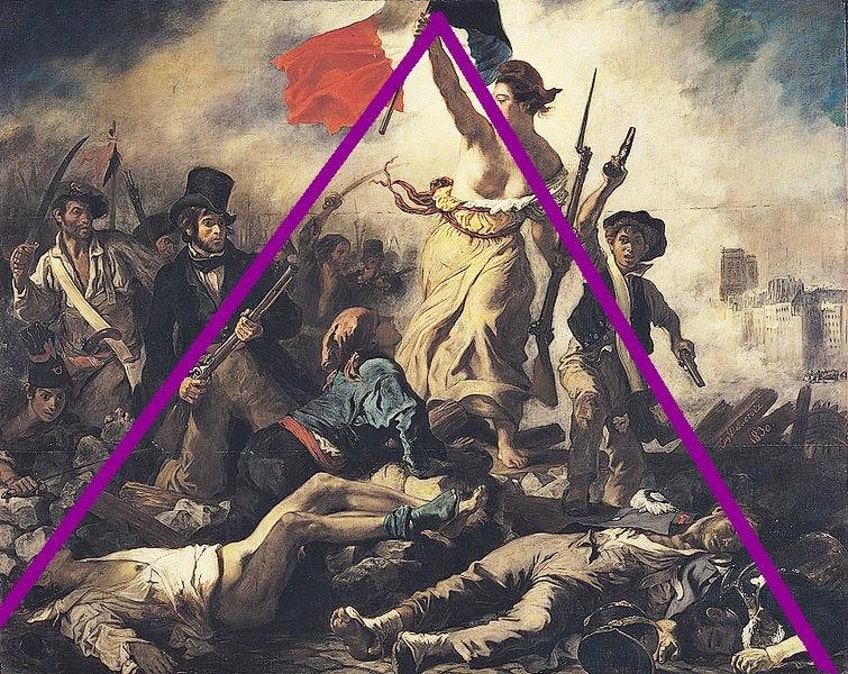

Below, we go into more detail in the Liberty Leading the People by Eugène Delacroix. It is important to remember that this French revolution painting is allegorical, which means it is symbolic of concepts like freedom and the French Republic.

Visual Description: Subject Matter

The Liberty Leading the People painting presents a scene filled with action and intensity, in which the central character is a woman surrounded by hundreds of men following her lead. Starting with the central figure, the woman is wearing a long yellow dress, which is open at her chest exposing her breasts.

Her face is depicted in profile, turned to her right-hand side, and she is looking over her right shoulder at the men following behind her. Her right arm (viewed from our left) is outstretched above her head as she brandishes the large tricolored French flag.

The tricolors that distinguish the French flag are, namely, blue, white, and red.

In her left hand (viewed from our right), which is lowered and near her waist area, is a large musket with a bayonet attached to its muzzle. She appears as a powerful force running forward, barefooted, over what appears to be a barricade.

She is also wearing a red Phrygian cap, which has been a longstanding symbol of freedom since ancient Roman times.

To her left (our right) is the younger figure of a boy distinguished by the two pistols in both hands, a satchel, and the black beret on his head, which is usually worn by French students and made of velvet and is referred to as a faluche.

To her right (our left) are several adult male figures; the one closest to the woman is wearing a top hat, a black coat, and holding a shotgun in both hands. Next to his left, to the far-left border of the composition, is another man wearing less formal attire, a beret on his head, a ruffled white shirt, and what appears to be an overall over it. He is holding a briquet saber in his right hand with a pistol fastened to his waist by a red and blue handkerchief.

From the rubble, crawling on all fours is a figure approaching the woman’s feet. He is peering up at her as if she is a figure of salvation. He is wearing black trousers, a blue shirt, and a red waistband and bandana otherwise referred to as an “infantry bicorne”.

These colors are reminiscent of the French flag.

There are several dead bodies strewn in the foreground of the composition; to the left, there is a man lying half-naked with only one sock on his lifeless feet. To the right, there are two other figures of men that appear to be clothed in military garb. We will notice how the background comes into our view by the boy on the right side, near the right middle ground border of the composition, depicting part of the Notre-Dame cathedral in Paris.

The rest of the background appears shrouded in smoke and throngs of people.

Color and Light

In Liberty Leading the People, there are neutral and earthy colors like whites, browns, and beiges in varying shades, giving the overall composition a color harmony. In the center we are met with the yellow from the heroine’s dress with various brighter tones of color here and there, for example, reds and blues, emphasizing the French flag’s colors. There is a deep blue in the sky above, almost visible through the fog of smoke in the background.

The foreground is lit up by an unknown lightsource, highlighting the central female figure representing Liberty, as well as the dead bodies.

Texture and Brushwork

Texture in the Liberty Leading the People painting is conveyed through Delacroix’s expressive and varying brushstrokes giving even more life to the composition. To name a few examples, the implied texture is evident in the clothing, notably Liberty’s draping dress, the foggy smoke lingering in the background, as well as the wood and stones strewn here and there.

Line, Form, and Shape

There is a close interchange between brushstrokes and line, form, and shape; the brushstrokes seemingly create the forms and shapes, for example, the buildings in the distance or the rich contours of the human figures.

Furthermore, there are no delineated outlines or indicated measured brushstrokes that we would see in Academic paintings, instead, each form and shape is created by the application of loose brushstrokes.

If we look further, there appears to be no order in this composition and there are various vertical and diagonal lines; the figures and forms all appear scattered, but Delacroix created some sense of order through the utilization of a pyramidal composition, with Liberty in the center position.

Space

The Liberty Leading the People painting is a large-scale artwork, measuring 260 x 325 centimeters. If standing in front of this painting we would be met by the intensity of the scene, more especially the foreground, which seemingly moves right into our space. This is emphasized by the figure to the left, whose arm is described by art sources as foreshortened, giving the illusion of space.

On the Edge of Freedom

Although Liberty Leading the People by Eugène Delacroix is not a depiction of the 1789 French revolution, it is still a French revolution painting depicting a moment in time when people from all types of social classes fought together, on the edge of their freedom.

There is no pretense or idealization of figures, only the realness of what revolution can lead to.

Furthermore, Liberty, here, is a symbol of freedom, one that has been immortalized through the years on postage stamps, coins, as well as in contemporary pop culture, as seen as a cover for the Viva la Vida or Death and All His Friends (2006) album cover for the music band Coldplay.

Take a look at our Liberty Leading the People webstory here!

Frequently Asked Questions

Who Painted Liberty Leading the People?

Eugène Delacroix, one of the leading figures in French Romanticism, painted the famous French revolution painting titled Liberty Leading the People (1830).

What Is the Liberty Leading the People Painting About?

The Liberty Leading the People (1830) painting is about the July Revolution in France in 1830. The revolution overthrew the then King Charles X. It is important to remember that this painting does not depict the events of the French Revolution, which occurred in 1789.

Is the Woman Real in the Liberty Leading the People Painting?

The woman in the Liberty Leading the People (1830) painting is not based on a real woman from history, but she is a symbol of freedom. She is often referred to as Marianne, a personification of the ideals of liberty in France.

Alicia du Plessis is a multidisciplinary writer. She completed her Bachelor of Arts degree, majoring in Art History and Classical Civilization, as well as two Honors, namely, in Art History and Education and Development, at the University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. For her main Honors project in Art History, she explored perceptions of the San Bushmen’s identity and the concept of the “Other”. She has also looked at the use of photography in art and how it has been used to portray people’s lives.

Alicia’s other areas of interest in Art History include the process of writing about Art History and how to analyze paintings. Some of her favorite art movements include Impressionism and German Expressionism. She is yet to complete her Masters in Art History (she would like to do this abroad in Europe) having given it some time to first develop more professional experience with the interest to one day lecture it too.

Alicia has been working for artincontext.com since 2021 as an author and art history expert. She has specialized in painting analysis and is covering most of our painting analysis.

Learn more about Alicia du Plessis and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Alicia, du Plessis, ““Liberty Leading the People” by Eugène Delacroix – A Detailed Analysis.” Art in Context. May 4, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/liberty-leading-the-people-by-eugene-delacroix/

du Plessis, A. (2022, 4 May). “Liberty Leading the People” by Eugène Delacroix – A Detailed Analysis. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/liberty-leading-the-people-by-eugene-delacroix/

du Plessis, Alicia. ““Liberty Leading the People” by Eugène Delacroix – A Detailed Analysis.” Art in Context, May 4, 2022. https://artincontext.org/liberty-leading-the-people-by-eugene-delacroix/.