Famous French Revolution Paintings – The Art of the French Revolution

The French Revolution is, without a doubt, one of the most influential events in all of social history. During this tumultuous period, painting became a way of reporting and commenting on the revolution, much like how we use social media today. At the same time, it also inspired painters to pursue new approaches to their work. Not only would the French Revolution change society forever, but art as well.

Famous French Revolution Paintings

The French Revolution is usually understood in three parts. During the first, the common class began the revolution by assuming political power at the Estates-General of 1789. French society under the Ancien Regime was disparate – taxes on the poor were high, shortages were common, and employment was scarce.

Commoners were fed up with this experience and wanted to establish a people’s France, one designed with the majority in mind.

The second phase witnessed the Reign of Terror and the fracturing of the revolution, which would then conclude in 1799 with the return of Napoleon to France and his seizure of government. This list travels through the French Revolution by examining the most famous French Revolution paintings, each with a story to tell.

Marie Antoinette with the Rose (1783) by Élisabeth Louise Vigée le Brun

| Artist | Élisabeth Louise Vigée le Brun (1755-1842) |

| Date Painted | 1783 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 116.8 cm x 88.9 cm |

| Currently Housed | Palace of Versailles, France |

| Price | Never sold |

Élisabeth Louise Vigée le Brun was a French painter known for her portraits of Marie Antoinette, Queen of France. Le Brun produced over 30 royalist portraits for the court. After gaining popularity at the Académie de Saint-Luc, she struck up a relationship with the queen and became her official portraitist. She is recognized as the only female French court painter.

She sparked controversy by presenting her portrait subjects with smiles, deemed unacceptable at the time.

In 1873 she was commissioned by Antoinette for a portrait, which Le Brun hoped to present at the Salon. Initially, Le Brun painted the queen wearing a muslin dress. Salon organizers found the painting insulting, believing that the queen should never be seen in such common or rural clothes.

Within a month, Le Brun quickly produced Marie Antoinette with the Rose to secure her spot at the Salon. This piece was received warmly by elite patrons, as Antoinette is depicted in a luxurious silk dress and exhibits a serious demeanor. In the previous version of the painting, the queen was portrayed smiling. Despite having to pander to Salon demands, Le Brun still managed to squeeze in creativity.

The queen is presented as almost trapped behind the rigid dress and pearls, a comment on the limitations placed on female artists and subjects. Le Brun’s painting is an example of Rococo, popular under the Ancien Regime and around Europe at the time. Rococo is a dramatic and theatrical style, inspired by nature and often focused on elite or antiquity subjects.

The fiasco surrounding the original painting indicates the vast social differences in 1700s French society.

The First and Second Estates consisted of royalty, clergy, and nobility. Antoinette’s presentation in this second painting, as a wealthy queen out of touch with her people, was already a prominent opinion amongst the Third Estate. These were the commoners who would later lead the Revolution.

The Storming of the Bastille (1790) by Jean-Baptiste Lallemand

| Artist | Jean-Baptiste Lallemand (1716-1803) |

| Date Painted | 1790 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 80 cm x 104 cm |

| Currently Housed | Musée Carnavalet, France |

| Price | Unknown |

The life of Jean-Baptiste Lallemand is less documented than other painters in this list. Hailing from Dijon, Lallemand spent much of his early career as a landscape artist in Italy. Enjoying success, he was commissioned by the Pope, and many of his Roman scenes were displayed back in France. Following his return home in the 1760s, Lallemand became a member of the Académie de Saint-Luc, observing the revolution as it developed.

By the time it kicked off in July 1789, he was prepared to project the great event onto canvas.

The storming of the Bastille was the breaking point of the French Revolution. En masse, revolutionaries attacked the grounds of the Bastille, taking control of its prison and armory. But this was not a feat to be measured in terms of military skill or conquest.

The physical presence of the Bastille was a symbol of power under the Ancien Regime, and its collapse meant that a new France was in the making. For Lallemand, these were not the peaceful landscapes of the Italian countryside. This was a landscape of the passionate fight for liberty.

Note how there are no discernible characters in this scene, let alone a protagonist. Lallemand was not interested in producing a grand narrative about this day, or about the people involved in it. Instead, he wanted to capture the experience from the perspective of the people, of which he was also proudly part. There is little organization to the scene, which is precisely how the siege played out in reality. The artist also engages in some realism here.

The event alone, with its raw chaos and energy, is important enough to stand alone without cosmetic glorification or narrative.

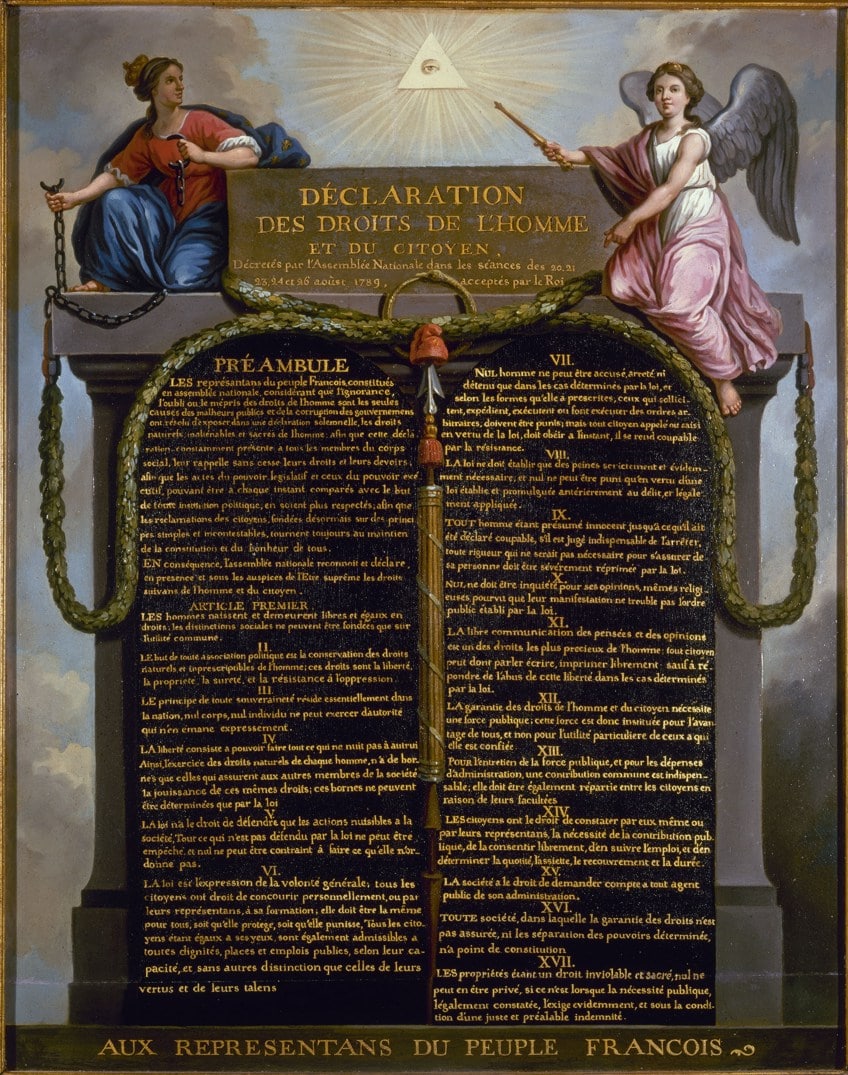

Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (c. 1789) by Jean-Jacques-François le Barbier

| Artist | Jean-Jacques-François le Barbier (1738-1826) |

| Date Painted | Circa 1789 |

| Medium | Oil on panel |

| Dimensions | 71 cm x 56 cm |

| Currently Housed | Musée Carnavalet, France |

| Price | Unknown |

Le Barbier was a highly revered artist under the Ancien Regime and during the French Revolution. He engaged himself widely across writing, illustration, and painting. Inducted into the Académie Royale in 1785, Le Barbier soon became an official court painter for Louis XVI. A champion of history painting, Le Barbier is also amongst those who were at the spearhead of the Neoclassical movement in France.

His closeness with the royal regime does not seem to have landed him in any trouble, however, as he adjusted his subject matter during the revolution. Declaration is an example of this pro-revolution shift and is regarded as his most famous work.

The painting is inspired by the key revolutionary document of the same name, developed by the new National Assembly in 1789.

The painting was marketed and distributed as a poster across France, especially with the idea that these be hung up in family homes – it was extremely popular. But just because it was a popular and widely reproduced piece does not mean Le Barbier did not summon his ingenuity for it.

The artist’s use of color is extremely fluid, lending to a pleasant and approachable view.

As a visionary light beams over the tablet, Marianne, the symbol of the French Revolution, decouples her chains and looks to the future. In turn, the angel on the opposite end of the tablet, blesses the Declaration of the Rights of Man, and consequently, the future of France.

The Lictors Bring to Brutus the Bodies of His Sons (1789) by Jacques-Louis David

| Artist | Jacques-Louis David (1748-1825) |

| Date Painted | 1789 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 323 cm x 422 cm |

| Currently Housed | The Louvre, France |

| Price | Never sold |

It is difficult to describe the French Revolution without considering Jacques-Louis David. He produced some of the most famous French Revolution paintings. An influential figure in the revolution, his work is inescapably political and offers unparalleled insight. A Parisian, the genius of David was noticed early, even if his caretakers initially resisted his artistic fascinations. After training in Italy, his return to France in 1780 was marked by a productive period in the years leading up to the revolution.

Politically, David associated himself with the Jacobins, the main political group behind the revolution.

Their leader was the influential Maximilien Robespierre. David produced propaganda pieces and saw himself as a reporter of the revolution. He organized revolutionary festivals, plays, and events, much to Robespierre’s delight. We can comfortably deduce that David saw himself as a revolutionary like any other, only his battleground was the canvas.

David’s first contribution to art in the revolution was subtle but resonated deeply with the movement. Despite being trained in the antique Rococo style, he always sought more animation. This dream would flower in the form of Neoclassicism.

Neoclassical painting was inspired by the classical works of the ancient world, but it sought to overcome the dramatic and detached styles of Rococo. Drawing heavily from Enlightenment ideals, these paintings were rationalistic, balanced (both in geometry and light), and often carried political, historical, or moralistic themes.

This painting was a continuation of the Roman theme David began to develop in “The Oath of Horatii” (1784/1785).

The work depicts Brutus and his family following the death of his two sons. In a display of civic self-sacrifice, Brutus ordered their deaths to save the Roman Republic. This motif was relevant in France at the start of the revolution, and David’s piece was immensely popular. Even though it was initially rejected from the Salon, the people’s pressure ensured it was displayed.

David comments on the revolution by invoking a moralist narrative from antiquity.

It illustrates the clash between new and old worlds – between monarchy and republic. The painting is markedly Neoclassical, making use of cool, dark colors and distributing light with moral direction. Brutus sits alone in darkness as his wife and daughters recoil at the horror under the light. His decision has isolated and depressed him, but the presence of the republican statue to the left indicates the worth of his sacrifice. Like most Neoclassical works, the brushstrokes are barely visible, resulting in a smooth and lively image.

The Tennis Court Oath (1790-1792) by Jacques-Louis David

| Artist | Jacques-Louis David (1748-1825) |

| Date Painted | 1790-1792 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas, pencil, bistre |

| Dimensions | 400 cm x 654 cm |

| Currently Housed | Palace of Versailles, France |

| Price | 24,000 French Francs (1835) |

The Tennis Court Oath is an unfinished French Revolution artwork by Jacques-Louis David, on which he worked between 1790 and 1794. Initially an engraving produced for the Salon of 1791, the painting ran into financial and political trouble in the years following. David wanted to depict the taking of the Tennis Court Oath by members of the Third Estate in 1789, which took place on the royal tennis court after the group was prevented entry to the chamber.

David wanted to portray this momentous event for the new government in Neoclassical style, hoping that the first engraving would fund the production of a full painting. But at six and a half meters long and four meters high, practically life-size, the painting was always bound to face challenges.

While most of the characters are in nude form, pockets of brilliance are visible. The high level of detail in the faces of the characters, where minimal brushstrokes can be noted, is achieved by employing a wash technique. David, who held a deep respect for the event, felt it his duty to accurately portray each attendee as a recognizable figure.

By painting recent history in a classical historical style, David infused the taking of the Oath with importance and hoped his audiences would appreciate the event. Symbolic winds of revolution blow over a unified and diverse group of revolutionaries, while the vast space above them points to a relationship with God.

Funding was not the only problem for this French liberty painting.

The political environment in 1973 had changed since the Tennis Court Oath. The National Assembly that had been established by the Oath was now fragmented. Many of the revolutionaries depicted in this painting were, by 1793, seen as enemies or traitors. The incomplete state of this painting reveals the gradual splintering of the revolution.

The Death of Marat (1793) by Jacques-Louis David

| Artist | Jacques-Louis David (1748-1825) |

| Date Painted | 1793 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 165 cm x 128 cm |

| Currently Housed | Royal Museums of Fine Arts, Belgium |

| Price | Never sold |

One of Jacques-Louis David’s most famous French Revolution paintings, The Death of Marat symbolized a dark turn in the revolution. As fighting between the Girondins and Robespierre’s Montagnards became more aggressive, Jean-Paul Marat was assassinated in July 1793. Marat was known for conveying the revolutionary message in pamphlets and publications. His assassin accused him of his involvement in the Reign of Terror, of which he was indeed guilty.

The Reign of Terror was a period that witnessed the execution of over 15,000 people.

Beginning with the purging of prisoners in September 1792, Marat’s death worsened the political climate, and things quickly became more gruesome. Anyone who was deemed counterrevolutionary could be detained and executed without a trial. Combined with food shortages and inflation, people quickly turned on each other, and the terror spiraled out of control.

With an emotional, realistic fervor, David portrays the stabbed Marat as a religious martyr. Light is distributed across Marat’s body in a Holy glow, common in Christian paintings of martyrs or scenes of sacrifice. The intensive use of contrast resembles that of Caravaggio. David saw here an opportunity to connect divinity (usually associated with the monarchy) with the revolution, thus empowering it. Also note how Marat’s bathroom has no decor, which was likely not the case in reality.

By relegating the background to a dark abyss, more focus is centered on the martyr, Marat, as he takes his final breaths.

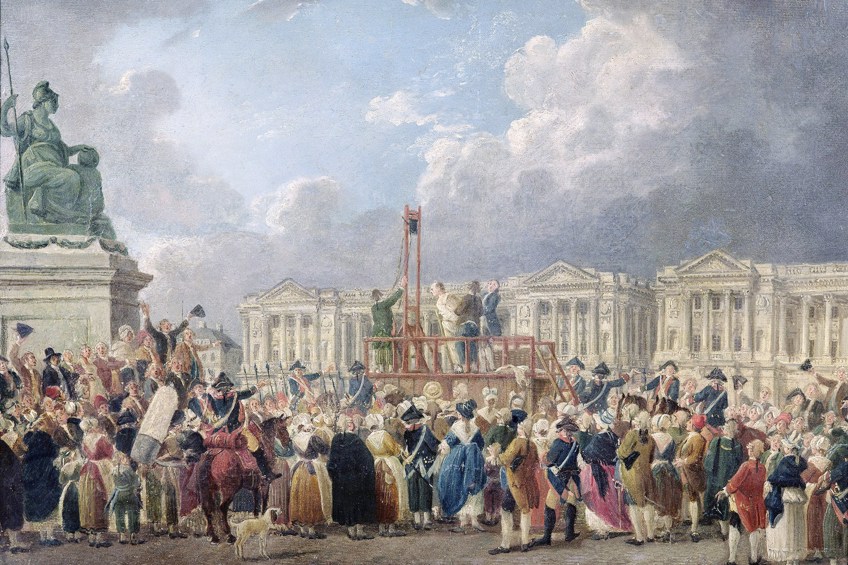

Une exécution capitale, la place de la Révolution (c. 1793) by Pierre-Antoine Demachy

| Artist | Pierre-Antoine Demachy (1723-1807) |

| Date Painted | c. 1793 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 37 cm x 53.5 cm |

| Currently Housed | Musée Carnavalet, France |

| Price | Undisclosed (1961) |

Pierre-Antoine Demachy was a respected artist before and during the French Revolution. His main focus was ancient ruins, and he was certified as an architecture painter by the Académie Royale as early as 1755. He was also a celebrated art educator, both at the Académie and at the Louvre.

During the revolution, Demachy contributed to the body of French Revolution art. While few in number, these paintings are particularly powerful. One of these paintings is Une execution capitale. It is at La Place de la Concorde, then called Place de la Revolution, a public square in Paris that witnessed some of the most significant events of the revolution.

This painting is likely from the early days of the Reign of Terror.

This scene depicts the execution of a counter-revolutionary and the jubilant crowd surrounding the guillotine. Only a few months before, Louis XVI was executed at this square, and Antoinette suffered the same fate one year later. Symbolically, back in 1770, the royal couple held their wedding celebration in this square. That evening, a fireworks display went wrong, and up to 3000 members of the public audience were killed.

The presentation of the built environment advertises Demachy’s core skill as an architectural painter, but he also emphasizes symbolic elements.

These include the isolated strength of Marianne’s statue, the revolutionary clothing of the public (including Phrygian caps), and the explicit distribution of light upon the guillotine, which powerfully sits at the center of the painting. The square would witness thousands of executions in the following years.

Portrait of a Revolutionary (1794) by Jean-François Sablet

| Artist | Jean-François Sablet (1745-1819) |

| Date Painted | 1794 |

| Medium | Oil on wood panel |

| Dimensions | 64.5 cm x 54.9 cm |

| Currently Housed | National Gallery of Victoria, Australia |

| Price | Undisclosed (2010) |

Jean-François Sablet was born into an artistic family from Morges, Switzerland. After moving to Paris, he and his brother joined the Académie and studied under the same master as Jacques-Louis David – Joseph-Marie Vien. His early work consisted of portraits and genre scenes with a calculated use of color and movement.

He and his brother were alternative Neoclassicists, still in line with the movement but known to mix Dutch influences into their work.

Despite his revolutionary beliefs, Sablet spent the early revolution in Rome, likely in search of economic opportunities. But by 1793, the rising terror back home prompted repressive reactions from neighboring governments, and he, along with other artists, was expelled back to France. Thereafter, he applied his portraiture skills to art in revolution, producing this famous French Revolution artwork.

The Reign of Terror worried many faithful revolutionaries across France. Their movement was turning into a display of paranoia, betrayal, and blood. In Portrait of a Revolutionary, Sablet depicts an officer of the local government, as indicated by the republican scarf on the table to the right.

The individual is not given a name, but psychological depth still pervades the painting.

The eyes of the revolutionary are laced with disillusion, after years of humble public service, and his weathered visage speaks for many of his comrades at the time. The personal intimacy that Sablet developed as a young artist, when painting elite portraits, comes to a crescendo here. The subject is likely Daniel Kervegan, mayor of Nantes.

Marie Antoinette being taken to her Execution (1794) by William Hamilton

| Artist | William Hamilton (1751-1801) |

| Date Painted | 1794 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 152 cm x 197 cm |

| Currently Housed | Museum of the French Revolution, France |

| Price | Unknown |

The only painting on this list not composed by a French artist is Marie Antoinette being taken to her Execution. William Hamilton was a painter from England known for his Shakespearean scenes. He was a member of the Royal Academy in England and also painted contemporary events, such as the piece presented here. The painting is Neoclassical, hesitant towards any grandeur, and dominated by a brooding, dark palette.

Hamilton produced the piece very late in his career, which may be the reason why it is strikingly neutral. He wanted to depict the incredibly difficult realities of the French Revolution during this period, from all sides.

Hamilton does not offer any insight into his own opinion on the revolution, as despite Antoinette’s almost angelic appearance, the crowd and guards do not appear as clear antagonists either. It is likely that Hamilton would have made full use of this opportunity for contrast had he intended to present the event with any specific political sentiment.

While not as famous as some other English painters, this work of revolution art is still heralded as one of the most famous French Revolution paintings. The Reign of Terror would only end with the execution of Robespierre himself in 1794.

Napoleon at the St. Bernard Pass / Napoleon Crossing the Alps (1802) by Jacques-Louis David

| Artist | Jacques-Louis David (1748-1825) |

| Date Painted | 1802 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 259 cm x 221 cm |

| Currently Housed | Château de Malmaison, France |

| Price | Never sold |

All while terror played out on French soil, the state of France was still engaged in warfare across Europe and North Africa. It was during these campaigns that a charismatic young general, Napoleon Bonaparte, rose to fame. Staging a coup upon his return to France in 1799, Napoleon’s political cunning allowed him to establish a new government in place of the fractured revolutionary leadership.

The French people had become tired of the political instability of the past decade, and the last thing on their minds was another revolution. With so much blood already spilled, Napoleon appeared attractive to the French public. While he maintained that France was still a republic, his authoritarian rule was, in some ways, similar to the Ancien Regime.

By 1804, Napoleon had proclaimed himself Emperor of France, and the revolution had come full circle.

In the final years of the revolution, Napoleon and David developed a relationship, and soon after the coup, David was commissioned to celebrate Napoleon’s rise on canvas. Possibly Napoleon’s most famous portrait, David valiantly portrays one of his successful military campaigns. Using the white canvas base as a source of light, the highly detailed scene is majestic and revives the idealism of Rococo – Napoleon actually traversed the Alps on a mule. David continues with this theme in The Coronation of Napoleon (1807).

This painting marked an incisive shift in French Revolution art. Much like under the Ancien Regime, the subject of art was less concerned with the experiences of the people and more so with the glories of the empire. The Salon had reverted to its original form, as a platform for elite patrons and ruling propaganda.

But Napoleonic Neoclassicism was also different from the one practiced in the period of revolution art. It involved more movement and action, preferred diagonal orientations, and picked up on a somewhat left-behind baroque style.

This was the birth of French Romanticism.

Demolition of the Chateau Meudon (1806) by Hubert Robert

| Artist | Hubert Robert (1733-1808) |

| Date Painted | 1806 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 113.3 x 146 cm |

| Currently Housed | J. Paul Getty Museum, United States |

| Price | €111,600 (Appraisal – 2016) |

Hubert Robert was another forerunner of the Romantic movement. Robert enjoyed a bourgeois upbringing in Paris and sharpened his early artistic skill in Rome. There he became infatuated with ruins, becoming his central subject, and he earned the nickname “Robert of the Ruins”. Due to his apolitical stance, Robert was imprisoned for a year under the revolutionary regime and narrowly escaped execution. Despite this, he still contributed several French Revolution artworks.

Not all revolutionary scenes had to be of people, as we have already seen with the symbolic power of the Bastille. Demolition of the Chateau Meudon depicts a scene from the revolution which took place more than ten years before composition. Chateau Meudon was the royal residence of the Ancien Regime, and it was ransacked during the revolution.

By 1803, the building had been completely demolished, but this did not prevent Robert from capturing its symbolic significance.

Robert was well-versed in capricci painting from his time in Rome. Capricci is an architectural painting style that blends fact and fiction for emotive effect. In this scene, the artist integrates features of the landscape that no longer exist to capture a moment trapped in time.

He presents the chateau with immense size and bright light to indicate its former importance, casting a shadow over the various characters engaged in its demolition. The central positioning of the chateau establishes a clear axis for the painting, which is a neoclassical technique, but his evocation of feeling (by recalling a lost moment through fiction) is of Romantic flavor.

Despite the return to an authoritarian government, it was clear that something had changed in the fiber of French art. Artists still appealed to the powers of the day, but art in revolution had instilled a creativity and independence they were not willing to abandon.

Robert’s piece, a semi-fictional chronicle of the revolution, released under a monarchic government, suggests that artists were still seeking new horizons The antagonism between Neoclassicist precision and the freedom of Romanticism characterized much of the early 1800s.

Liberty Leading the People (1830) by Eugène Delacroix

| Artist | Eugène Delacroix (1798-1863) |

| Date Painted | 1830 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 260 cm x 325 cm |

| Currently Housed | The Louvre, France |

| Price | 3000 French Francs (1831) |

Eugene Delacroix’s French liberty painting is one of the most famous of the French Revolution. The only problem is that it does not depict a scene from the original French Revolution at all. In Liberty Leading the People, Delacroix was more directly inspired by the July Revolution of 1830, but this does not mean that a relationship does not exist. The painting is regarded as one of the finest works in the Romanticist style – a perfection of the early Romantic explorations of David, Robert, and other artists following the end of the revolution.

If Neoclassicism was about achieving perfection of form, Romanticism was about celebrating imperfection, and the belief that nature could never be fully contained, described, or represented. Romanticism was preoccupied with conveying the intensity of emotion and feeling however the artist saw fit.

This style was rooted in freedom of expression and rejection of constraints, and it went on to become a vital influence on the Impressionist movement.

Romanticism provided creative space for artists. Delacroix’s inclusion of a “living” metaphorical symbol, the lady of liberty, is a prime example. Disorganized but controlled, the flurry of movement and characters is another typical feature of this style.

By personifying the concept of liberty, the painting is given an emotional dimension – leaders die, but ideas live on. She marches over corpses, a collective symbol of all who had perished in the quest for freedom. She is surrounded by revolutionaries of different social classes, which is Delacroix’s way of stressing the unity that is essential to building a new nation.

What remains most important in the takeback from Delacroix’s masterpiece is the way we see the revolution still breathing through it.

Even though the work originates from a different point in French history, the power of the people and the demand for liberty is expressed with just as much emotion as those who proudly marched on the Bastille 40 years before. At the practical level, Delacroix’s Romanticism owes heavily to the artistic freedom of his period, a freedom that may have never been enjoyed without the social changes initiated by the French Revolution.

French painting and the French Revolution were bound in a complicated relationship. The Revolution provided an opportunity to pull away from the rigid, elite styles of the Ancien Regime, but it also destabilized the social context, forcing painters to stay on their toes and quickly shift subject or tone. It was also the start of artistic independence in France.

Take a look at our French Revolution paintings webstory here!

Frequently Asked Questions

What Does French Revolution Painting Encompass?

Paintings of the French Revolution are paintings composed either in the years leading up to the Revolution, during the years of the physical revolution (from the Bastille to the Terror), or at the end of the Revolution. Many painters have also depicted the revolutionary period years after its conclusion. These are also included as famous French Revolution paintings. And while most of these paintings are by French hands, foreign artists have also expressed themselves by portraying the French Revolution.

How Did Painting Change During the Revolution?

Before the French Revolution, the dominant painting style was Rococo. Usually focused on grand, natural elements, art in revolution instead saw artists experiment with new styles, with Neoclassicism quickly becoming the most popular. The return of Napoleon meant the return of an elite and idealist focus, but this period also witnessed the beginnings of Romanticism.

Why Are Paintings of the French Revolution Important to Art as a Whole?

French Revolution paintings are important because they reveal the intense bond between art and society. The shift from Neoclassicism to Romanticism at the end of the revolution symbolized a larger conflict between philosophical beliefs. Neoclassicism was based on Enlightenment rationality and strove for perfection. Romanticism, inspired by the Revolution’s ideals of liberty, focused on artistic freedom and expression. The French Revolution should be seen as an important event in the long struggle for artistic independence.

Armin Kific is a social and political researcher and writer based in Pretoria, South Africa. He completed a degree in Political Science with majors in History and Philosophy in 2020 and has since completed an Honours in Anthropology and History. He is also currently pursuing a Master’s degree in Social Sciences from the University of Pretoria. Armin’s knowledge of the arts spans various mediums, and he is always looking for ways to marry art with social science. In 2021, he produced a short documentary film about the often-forgotten South African soul star Mpharanyana, integrating history, music, photography, and film. Armin is well-versed in art history, especially in the fields of political artwork and ancient artifacts. He enjoys exploring art history sources for information that has been lost or overlooked. He is also trained in biographical writing.

His favorite art movements include baroque, surrealism, and neoplasticism. Armin is an ardent supporter of indigenous art in South Africa and is involved in an organization that looks to uplift South African artists following the challenges of Covid-19. By writing for ArtInContext, Armin continues to cultivate his artistic creativities and unite perspectives between art and society.

Armin has been working for artincontext.org as an author and content writer since 2022. He writes about the topics of art history, specializing in political artworks and ancient artifacts.

Learn more about Armin Kific and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Armin, Kific, “Famous French Revolution Paintings – The Art of the French Revolution.” Art in Context. May 18, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/famous-french-revolution-paintings/

Kific, A. (2022, 18 May). Famous French Revolution Paintings – The Art of the French Revolution. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/famous-french-revolution-paintings/

Kific, Armin. “Famous French Revolution Paintings – The Art of the French Revolution.” Art in Context, May 18, 2022. https://artincontext.org/famous-french-revolution-paintings/.

Great source of information. Thanks for putting it all together here like this.