Lawrence Weiner – A Figurehead of the Conceptual Arts Movement

Lawrence Weiner is an important artist who helped propel the Conceptual Art movement forward during the 1960s. Initially, he thought of himself as more of a sculptor as opposed to a conceptualist, yet the artworks he created challenged the radical definitions of art that still existed during that time. Thus, Weiner is considered a central figure within the movement, with the development in his artworks taking on the form of typographic texts.

A Brief Lawrence Weiner Biography

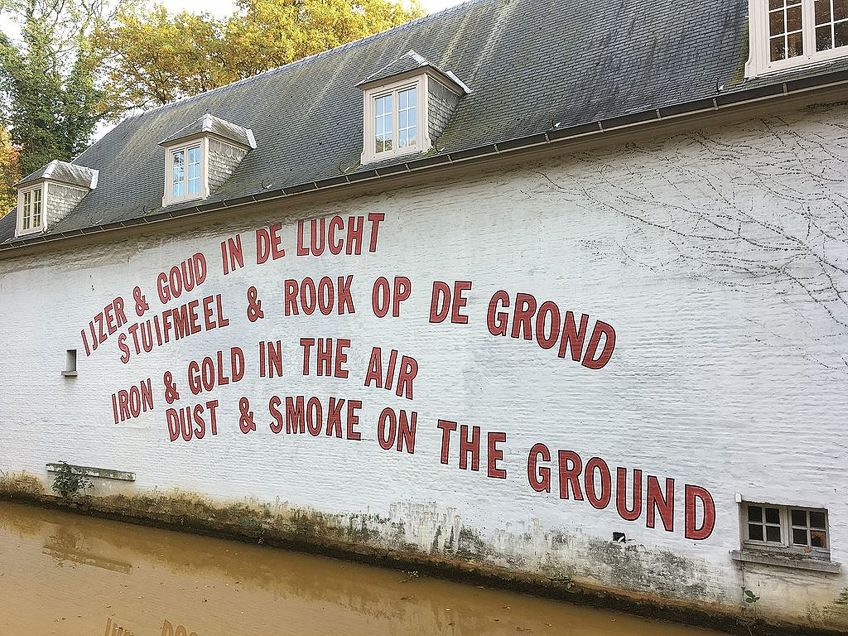

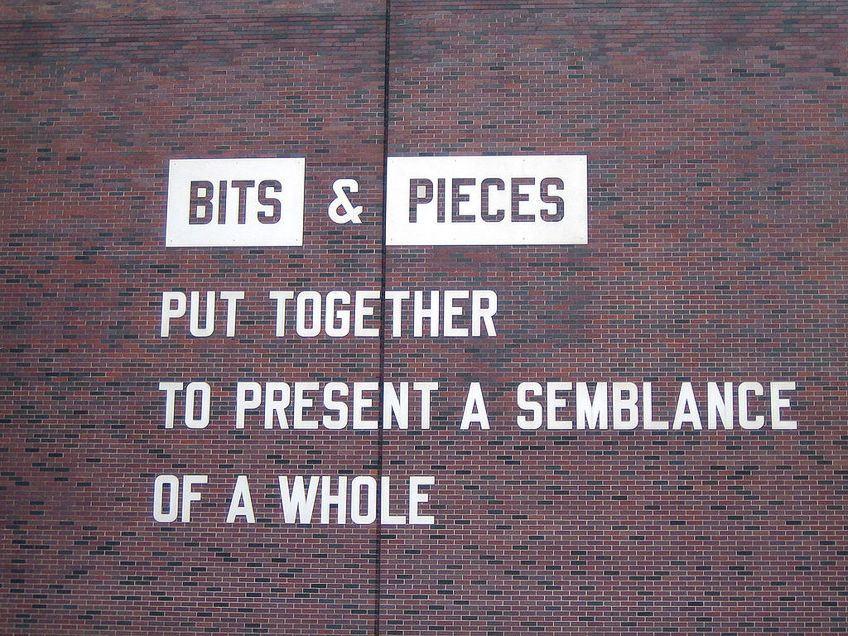

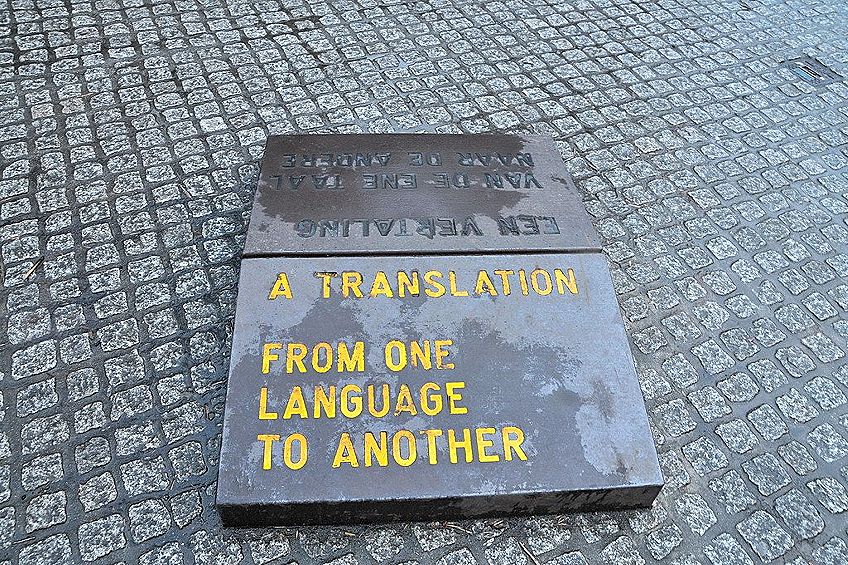

Over the last five decades, Lawrence Weiner art, consisting of words, has appeared in all kinds of places. Weiner (born February 1942) is an American conceptual artist and is known as one of the central trailblazing figures to form the Conceptual Art movement within the 1960s, along with artists Sol Lewitt, Robert Barry, and Joseph Kosuth. He is best known for his text-based artworks and installations and was among some of the first artists to slowly shift the object of art into an aesthetic that was purely language-based.

Today, the artworks spanning his lengthy career are housed in the collections of New York City’s Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, the Art Institute of Chicago, the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C., the Tate Gallery in London, and the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris.

Born in the South Bronx, New York City, Weiner graduated from high school at the age of 16 and went on to work in a variety of occupations within the manual labor field before deciding to go study. These included working on an oil tanker, on docks, as well as offloading railroad cars. Weiner went on to briefly study at Hunter College before deciding to drop out and travel throughout North America.

After his extensive travels, Weiner returned to New York before his first official exhibition in 1964 and 1965, which took place at the Seth Siegelaub Contemporary Art Gallery. His work that was featured demonstrated his experimentation with methodical approaches to canvases, and displayed squares that were cut out of carpeting and walls.

Prior to Weiner finding his niche within typography-based artworks, he previously worked with mediums including video, books, film, sound art within audiotapes, performance art, installation art, graphic art, and sculpture. However, since the late 1960s, Weiner’s artwork began to employ his primary medium to create text-inspired art.

Weiner demonstrated an elegant yet functional approach when choosing striking fonts and monochromes, with his choices often either stenciled, painted, or inscribed onto different surfaces and walls.

In 1968, a turning point occurred in Weiner’s career when he created work for an outdoor exhibition that was organized by Seth Siegelaub at Windham College in Vermont. Weiner attempted to define the space for his work through unnoticeable means by forming a grid over the ground with twine stretching from regular intervals.

The idea behind this was to create a rectangle removed from a rectangle, but students crossing the ground began to cut the twine away instead of walking around it as it obstructed their access. This led Weiner to the idea that perhaps the piece would have had the same impact had it been simply verbally described and not been built at all.

This led Weiner to his Declaration of Intent (1968), developed during the peak of Abstract Expressionism, in which he critiqued the essence of art by making a list of oversimplified written jargon that could stand in place of all physical artworks. Through this, Weiner was one of the first artists to rethink the position of artists in relation to their work and proposed a new relationship with art.

Thus, throughout his artworks, one can see Weiner’s attempt to render his work impartial, accessible, and thus applicable for a wider and more diverse audience.

By the early 1970s, Weiner’s artworks firmly consisted of language and text fragments that were presented in either capital or lowercase letters, with accompanying graphic marks and lines. While language can essentially be displayed in any form, Weiner’s great attention to detail regarding the size of the font chosen, where the letters and paint should be placed, and the type of surface texture used essentially allowed him to invent new fonts within his artworks.

Weiner considered language to be like a sculptural material that could be constructed and shaped as easily as any physical artwork. Thus, his work has been interpreted into multiple languages and his art pieces have appeared on the windows and walls of galleries and public spaces all over. Over the years, his spoken words have been turned into video and audio recordings, books, posters, tattoos, lyrics, and even graffiti.

Mostly self-taught, Weiner’s desire to make art more widely available and engaging with a broader audience arose from his childhood in the South Bronx. His installations take on a form of merely leaving messages for other people to read as opposed to becoming a historical piece of work, as the words and meaning can change over time. Thus, Weiner’s artworks experimented with different types of display and distribution that questioned the conventional assumptions about the purpose of the art object

Today, Weiner lives and works in New York City, as well as Amsterdam. Throughout his career, his work has been the topic of many exhibitions and from 2007 to 2008, he was the focus of a retrospective exhibit that was put on at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York and the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles. Weiner’s artworks influenced many other artists such as Barbara Kruger, Felix Gonzalez-Torres, and Jenny Holzer.

The Artistic Style of Lawrence Weiner

Weiner defined his artistic medium by simply joining language and the material that was referred to within his art piece. He viewed language as a site for construction and thus molded artworks purely out of words that captured ideas and meaning. Weiner essentially translated his studio work into words by communicating the subject matter of each work without indicating any of its tangible characteristics.

Within the descriptions of his work, Weiner would describe the material components, colors, boundaries, and interactions that were used in each piece in order to allow viewers to form their own understanding and interpretation of the work. While Weiner does not view his works as site-specific, each piece manages to build a loose relationship to whatever cultural and urban environment it is placed in.

At the start of his career, Weiner was working during the peak of Abstract Expressionism. His debut piece, titled Cratering Pieces (1960), was exhibited when he was 19 years old and consisted of explosives that were set to go off at the same time in four corners of a field. Weiner worked without permission to create random sculptures out of the craters that were left by the explosions, demonstrating the theme of abstraction in this early work.

This type of anti-establishment art set the stage for the development of the Conceptual Art movement and helped propel Weiner into the defining artistic style that would later go on to frame his career.

From 1960 to 1965, Weiner began to work on Propeller paintings, which were inspired by the patterns that appeared on the television screen at night once all the scheduled programming had ended. These pieces demonstrated his interest in incorporating minimalism into his works, which he continued to do so as his style evolved.

Weiner became known for the style of his earlier works, which led to him beginning to exhibit at New York’s Seth Siegelaub Contemporary Art Gallery in 1964. It was at this exhibition where students began to dismantle his Hay, Mesh, String artwork. This prompted a great shift in Weiner’s work, as it triggered his fundamental idea that it did not matter if an artwork was produced or not, and that artwork did not necessarily need to be physically constructed to exist.

Since the early 1970s, Weiner’s primary medium focused on wall installations that integrated language. During this time, he continued to work within a range of other media, such as film, video, book, sound art, sculpture, installation art, performance art, and graphic art. However, his use of language stood out as his preferred media choice, with the artworks that he began painting on walls consisting only of words in ordinary lettering.

Weiner demonstrated that for his art pieces to be created, the lettering did not necessarily need to be done by himself. As long as the painter adhered to the instructions dictated by Weiner, his pieces would come into existence. The development of Weiner’s artistic style focused on the possibility for language to exist as an art form by itself, with the addition of materials considered less important.

In the following years, Weiner began to explore the engagement between punctuation, color and shapes to provide rhythm and meaning within his texts. This is demonstrated in his 1997 installation titled Homeport, in which visitors can explore an interactive environment that was defined by linguistics as opposed to features.

The central motivation within Weiner’s work was to make his art pieces accessible to a wider audience, who would not require a ticket or the specified artistic knowledge to understand and appreciate the works. Weiner believed that through the use of language, he could reach a broader audience outside the context of traditional museum galleries and exhibitions. Through creating works in public spaces, Weiner successfully removed cultural establishments that would have excluded his larger and more diverse audiences.

Lawrence Weiner statements and phrases, which are typically created in Franklin Gothic Extra Condensed font, combine the procedures, supplies, structures, and the outcome of executing a process. His work titled Many Colored Objects Placed Side by Side to Form a Row of Many Colored Objects (1982) encompasses his artistic style as he provides the process and the results within the title and phrases used.

Additionally, some of Weiner’s phrases were unique to specific spaces, while others were repeatedly installed in various locations. This perfectly encapsulates the versatility of Weiner’s chosen artistic style, as identical words and phrases will essentially carry different meanings and experiences within different contexts.

Weiner’s Most Famous Artworks

When considering his most well-known pieces, Lawrence Weiner statements and language pieces form part of his most prolific works. Throughout his career, Weiner’s linguistic-based sculptures remain his most talked-about artworks. Due to this, the majority of his pieces are equally celebrated and admired, with no work made to be superior to the others. A selection of his most recognizable works has been chosen below.

Cratering Pieces

This sculptural and earth-based experiment, created in 1960, existed as Weiner’s first work of notable interest. This involved Weiner setting up a series of explosives in a state park and declaring the aftermath of the detonations to form sculptures. This artwork marks the beginning of his career, as this form of artistic rebellion would later pave his way into the Conceptual Art movement and his use of language as his primary medium.

Declaration of Intent

Created in 1968, Declaration of Intent exists as Weiner’s initial entry into conceptual art. Within this artwork, he began to adopt language as the primary vehicle for his work, as the artwork consists of three simple terms which he believed described the creation of art.

In his statement, Weiner claimed that an artwork could remain conceptual and exist purely in the form of language, or it could be created if required. This artwork went on to act as a guide for attempting to understand all Weiner’s works, as it demonstrated his unbiased thinking towards the making and viewing of art.

Fire and Brimstone Set in a Hollow Formed by Hand

One of Weiner’s more iconic typographic works, created in 1988, was titled Fire and Brimstone Set in a Hollow Formed by Hand. This artwork exists as a loose template upon which all his following language-based works were created.

The text, written in blue and encapsulated by a blue box, became a typical style of Weiner’s throughout the 1980s. It featured snippets of phrases, displayed at a slant, in a way that became reminiscent of a nonsensical poem. This artwork was wrapped around a railway bridge and formed part of a public exhibition. Since his work was essentially exhibited in a three-dimensional space, Weiner was able to emphasize the sculpture-like character of his works despite them being made up of only words.

This artwork exists as an important example of the site-specific installations that Weiner would go on to create, as well as the reduced visual character that was present in conceptual art during the 1980s.

Most Notable Exhibitions

Throughout his lengthy and established career, Lawrence Weiner has been the subject of many gallery exhibitions. Some of his most notable exhibitions have taken place between 2007 and 2019. Some of his most recent Lawrence Weiner art exhibitions have taken place at the Jewish Museum in New York (2012), the Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona in Spain and the Villa Panza in Italy (both in 2013), the South London Gallery, and the Blenheim Art Foundation in the United Kingdom (2014 and 2015), the Kunsthaus Bregenz in Austria (2016), the Milwaukee Art Museum (2017), and the Museo Nivola in Italy (2019).

Weiner’s most recent exhibition was titled TRACCE/TRACES and took place in August 2020 at the Museo d’Arte Contemporanea in Rome, Italy. This collection renounced the conventional spaces associated with gallery exhibitions as it urged audiences to look up into the sky at a series of aerial banners that were displayed along the Italian coast. Ten banners, which changed every day, displayed single words suggesting an activity that could have happened in the past or one that could occur in the future.

The intent for this exhibition was to allow the words to open themselves up to interpretation as they were removed from any grammatically correct context. Weiner’s work was made as a tribute to Germano Celant, the Italian curator who published a book under the same name in 1970.

Recognition

Lawrence Weiner has been the recipient of many awards throughout his career, with his most notable achievements being the National Endowment for the Arts award received in 1976 and 1983, as well as a Guggenheim Fellowship awarded in 1994.

Other awards include the Wolfgang Hahn Prize (1995), a Skowhegan Medal for Painting/Conceptual Art (1999), an Honorary Doctorate of Humane Letters from the City University of New York (2013), the Roswitha Haftmann Prize (2015), and the Wolf Prize and the Aspen Award for Art (both in 2017).

Other Work: Writing and Films

Weiner’s first and most well-known book, written in 1968 and titled Statements, was a contribution to a project organized by Seth Siegelaub. This work consisted of nothing but oversimplified words that were used to describe how to produce art and were written in response to the students who dismantled Weiner’s Hay, Mesh, String artwork that was being exhibited in 1964 in Vermont. This experience shaped the artistic style that Weiner began to adopt.

The book consisted of 24 typed processes that one needed to follow to produce art, with Weiner using words and descriptions written in the past participle that were clear but not too direct, suggesting that an artwork’s existence required a readership as opposed to a material presence. Statements essentially demonstrated Weiner’s shift towards language as his primary medium and is considered one of the most innovative conceptual artist’s books of the era.

Within the same year, Weiner also contributed some pages to Siegelaub’s book titled Xeroxbook, which featured a collection of photocopies from seven conceptual artists. Apart from books, Weiner has also produced many films, such as Beached (1970), Do You Believe in Water? (1976), and Plowman’s Lunch (1982).

Suggested Reading

Conceptual Art is indeed an interesting movement to learn about, with Weiner’s works captivating the essence of the movement. If you enjoyed reading about the art created by Lawrence Weiner throughout his career, we have suggested a book below that goes into greater detail about his life and artworks.

Lawrence Weiner: AS FAR AS THE EYE CAN SEE 1960-2007 (Whitney Museum of American Art)

Published in 2007, this book takes a comprehensive look at Weiner’s noteworthy then 40-year career, which has gone on to reach new heights. As one of the defining figures of Conceptual Art, this book represents the full range of Weiner’s career and documents his early paint works as well as his linguistic-based work which became his primary medium. The book is extremely well structured and contains illustrations for the different content.

- A comprehensive look at the remarkable career of Lawrence Weiner

- A substantial publication produced in close collaboration with the artist

- Brings a number of esteemed scholars to examine the artist's impact

Lawrence Weiner art enabled the start of the Conceptual Art movement, as his works existed as some of the most significant pieces within the movement. His typographic works have remained iconic throughout his career, with Weiner’s radical approach to art inspiring the idea that artworks need not physically exist to still be considered as art. Today, Weiner continues to produce his distinctive language-based works.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Lawrence Weiner – A Figurehead of the Conceptual Arts Movement.” Art in Context. March 12, 2021. URL: https://artincontext.org/lawrence-weiner/

Meyer, I. (2021, 12 March). Lawrence Weiner – A Figurehead of the Conceptual Arts Movement. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/lawrence-weiner/

Meyer, Isabella. “Lawrence Weiner – A Figurehead of the Conceptual Arts Movement.” Art in Context, March 12, 2021. https://artincontext.org/lawrence-weiner/.