Giotto di Bondone – The Life and Art of Giotto the Renaissance Painter

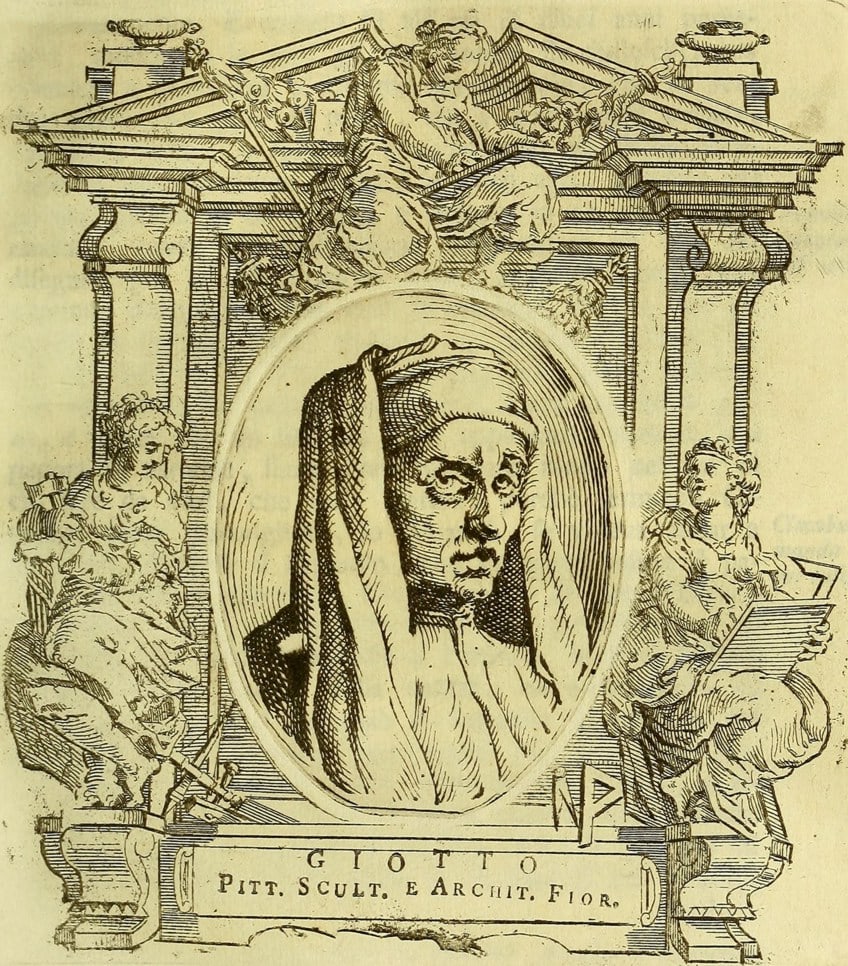

Who was Giotto di Bondone? Giotto the artist is regarded as among the most influential artists in the history of Western art. Giotto di Bondone’s art introduced a new age in the arts that combined spiritual antiquity with the nascent notion of Renaissance Humanism, predating by a hundred years many of the fascinations and issues of the Italian High Renaissance. Furthermore, many historians feel that the painter Giotto’s effect on European art was unrivaled until Michelangelo assumed his role 200 years later.

A Giotto di Bondone Biography

Giotto the artist is most known for probing the potentials of perspectives and aesthetic space, giving his religious stories a new sense of realism. Painter Giotto’s concern with humanism led him to investigate the contradiction between biblical imagery and the ordinary lives of lay worshipers, with the goal of bringing people nearer to God by creating art more appropriate to their personal experiences.

Giotto’s Renaissance characters were therefore imbued with an emotional intensity hitherto unseen in fine art, whereas his architectural surroundings were represented in accordance with optical rules of perspective and proportion.

Giotto the artist was considered by his peers to be the most authoritative virtuoso of art in his day, drawing all of his figures and poses according to reality and his publicly acknowledged aptitude and quality. He broke with the prevailing Byzantine style and pioneered the wonderful style of painting as we understand it today, inventing the skill of drawing precisely from reality, which had been abandoned for more than 200 years.

| Nationality | Italian |

| Date of Birth | c. 1267 |

| Date of Death | 8 January 1337 |

| Place of Birth | Florence, Italy |

The Childhood of Giotto di Bondone

Giotto is said to have been raised in a farmhouse. Since 1850, a tower house in adjacent Colle Vespignano has carried an inscription proclaiming the distinction of his birthplace, a claim that has been widely advertised. Recent research, however, has revealed documentary proof suggesting he was actually born in Florence, the child of a blacksmith. Bondone was the name of his father. He is considered to have been the child of a farmer, originating in the Mugello, a hilly region north of Florence that was also the homeland of the Medicis, who rose to prominence in the city.

Some historians believe he was born around 1277, but other sources believe he was born in 1267, which appears more plausible based on the sophistication of several of his early pieces.

Early Training and Career

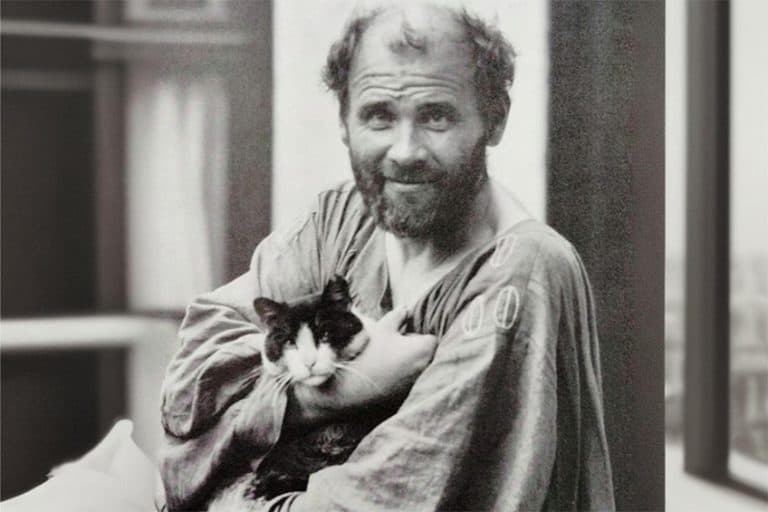

According to Vasari, in his youth, Giotto di Bondone was a shepherd boy, a happy and brilliant youngster who was adored by all who encountered him. Cimabue, the famous Florentine artist, came upon Giotto sketching drawings of his flock on a rock. Cimabue called on Giotto and asked if he may bring him on as an assistant since they were so lifelike. Vasari tells several accounts of young painter Giotto’s talent.

He recalls a day when Cimabue was not there at the studio and Giotto put a stunningly realistic fly on the forehead in a picture of Cimabue. When Cimabue arrived, he attempted to flick the fly away many times. Many contemporary experts are skeptical of Giotto’s instruction and regard Vasari’s assertion that he was Cimabue’s student as mythical; they cite older materials that imply Giotto the artist was not Cimabue’s student.

The fly narrative is especially suspicious since it resembles Pliny the Elder’s narrative about Zeuxis depicting grapes so realistically that birds sought to nibble at them.

Whatever the real origins of their professional connection, it is probable that Giotto was taught by Cimabue, most likely starting around the age of ten, where he acquired the craft of painting. According to Vasari, when Pope Benedict XI sent out an envoy to Giotto and asked him to produce a picture to illustrate his expertise, the painter Giotto drew a red circle so flawless that it appeared to be done with a pair of compasses and told the envoy to submit it to the Pope.

The messenger was dissatisfied and left, feeling he had just been made a complete fool of. Along with Giotto di Bondone’s art, the courier returned to the Pope paintings by other painters. When the messenger described how he had completed the circle without lifting his arm or using compasses, the Pope and his consorts were astounded at how Giotto’s talent was far beyond that of his contemporaries.

Although Cimabue was Giotto’s instructor, the pupil quickly surpassed his master, and his talent was acknowledged during his lifetime by contemporaries such as poet Dante Alighieri, who wrote “Oh, the vain pride of human talents! Cimabue expected to retain the field, but now Giotto has the voice, and the other’s glory is lessened.”

Giotto is said to have traveled to Rome with his teacher before following him to Assisi, where he had been appointed to adorn two churches just erected to celebrate St Francis. Although Cimabue traveled to Assisi to paint numerous big murals for the new Basilica in Assisi, it is conceivable, but not confirmed, that Giotto accompanied him. The provenance of the mural cycle of St. Francis’ Life in the Higher Church has become one of the most contentious in art history.

Because the Franciscan Friars’ documentation pertaining to artistic contracts during this era were destroyed by Napoleon’s forces, who stabled animals in the Upper Church of the Basilica, experts have contested Giotto’s attribution.

In the lack of contradictory evidence, it was simple to credit any mural in the Upper Church that was not clearly by Cimabue to the better-known Giotto. It was also speculated that Giotto may have executed the paintings ascribed to the Master of Isaac. Art experts investigated all of the Assisi paintings in the 1960s and discovered that part of the paint included white lead, which was also used in Cimabue’s severely deteriorating Crucifixion (c. 1283). This medium is not used in any of Giotto’s known works. Nevertheless, Giotto’s paintings of St. Francis’ Stigmatization (about 1297) have a theme of the saint propping up the crumbling church, which was previously incorporated in the Assisi murals.

The attribution of several panel paintings attributed to the painter Giotto by Vasari, and some others, is as much debated as the Assisi paintings. Giotto’s initial efforts, according to Vasari, were produced for the Dominican monks at Santa Maria Novella. They feature a mural of The Annunciation and a massive hanging Crucifix that is about 5 meters tall.

It was completed in 1290 and is assumed to be contemporaneous with the Assisi paintings.

Many researchers have questioned Giotto’s authorship of the Upper Church paintings. Without evidence, attributing claims have depended on connoisseurship, a typically untrustworthy “scientific method,” but in 2002, technical investigations and analyses of the studio painting techniques at Assisi and Padua produced credible proof that Giotto the artist did not produce the St. Francis Cycle.

Mature Period

Giotto wedded a Florentine lady named Ceuta in 1290, with whom he had several children. Someone reportedly asked Giotto the artist how he could make such beautiful paintings yet generate such hideous offspring, to which he answered that he produced his offspring in the dark. Giotto completed his first significant work at Assisi from 1290 to 1295, during which he achieved a number of notable graphical improvements.

Giotto di Bondone’s art was well received, and he was appointed to produce a new cycle of murals for the cathedral.

Giotto started a period of constant travel throughout the regions of Italy after a reasonably long stay at Assisi, a trend that would define his entire career. Giotto established studios in a variety of locales where his technique was replicated and where several of his helpers went on to launch their own careers. Giotto journeyed to Rimini, Florence, and most likely Rome around the turn of the century.

He then spent several years in Padua concentrating on the Arena Chapel, one of his most significant and well-known masterpieces. Giotto may have encountered the poet Dante, who was exiled in Padua from Florence, during his time there.

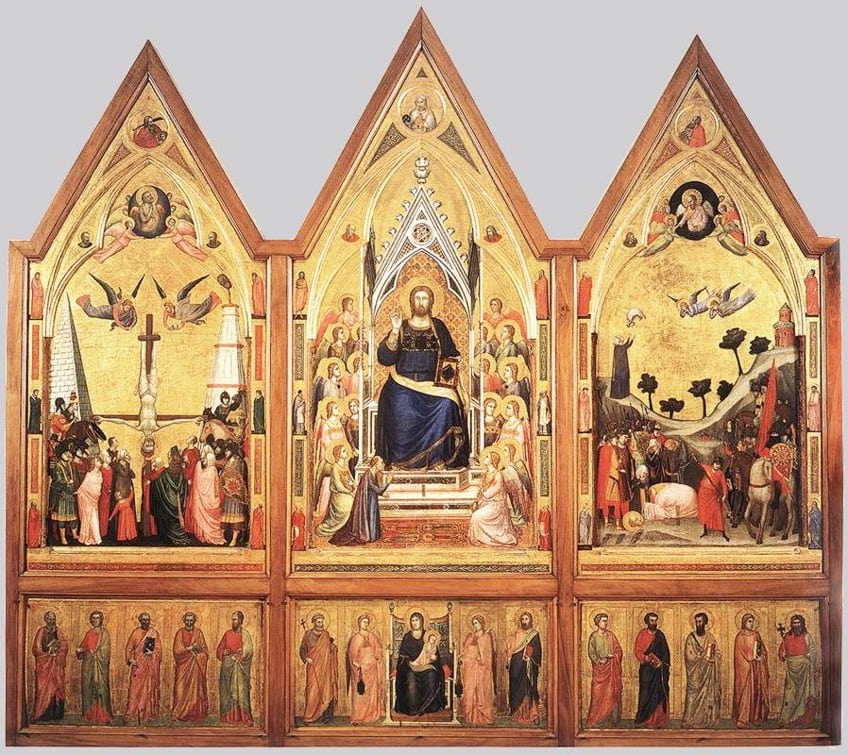

Giotto appears to have traveled from Florence and Rome many times between 1305 and 1315. He embarked on assignments for some of the most prominent churches. The seat of the pope in the early 1300s was not in Rome, but rather it was located in Avignon, France. The cardinals of Rome were battling for the restoration of the pope in their city and commissioned Giotto to create works such as a mosaic for the façade of the ancient St. Peter’s Basilica (of which only pieces exist), Rome’s most important papal basilica. Cardinal Stefaneschi expressed optimism that the Pope will return and begin to elevate the spiritual significance of his Roman seat.

As part of his political strategy, Stefaneschi is supposed to have commissioned Giotto, who was by this time a well-known professional painter.

During this time, Giotto also got significant contracts for the Florence church of Santa Croce. Meanwhile, circa 1313, he was working on a chapel devoted to the Peruzzi’s, a wealthy and powerful family of bankers, for whom he made two murals portraying John the Baptist and John the Evangelist. The individual of the Peruzzi household who made the request was named Giovanni and the paintings would seem to be meant to make a relationship between the household, the town of Florence, and the guardian saints that they adored.

The Peruzzi Chapel was highly regarded by Renaissance artists. Indeed, Michelangelo is believed to have studied the paintings in the ancient structures that highlighted Giotto’s mastery in chiaroscuro and his aptitude to effectively express perspective.

It is also known that Giotto’s compositions impacted Masaccio’s production on Cappella Brancacci later on.

According to surviving financial documents, Giotto also produced the renowned altarpiece the Ognissanti Madonna, which is currently held at the Uffizi, between 1314 and 1327. Though Giotto resided in Florence for a time, it is believed that he traveled to Assisi sometime around 1316 and 1320 to concentrate on the lower church’s decoration. When Giotto returned to Rome in around 1320 or 1330, he finished the Stefaneschi Triptych for Cardinal Jacopo.

Late Period

Robert of Anjou, King of Naples, called Giotto to his court in 1328. The Bardi household, for whom he had lately produced a series of murals for the household chapel in the church of St. Croce, may have suggested him to Robert of Anjou. Meanwhile, in Naples, Giotto became a court artist, giving up the more dangerous nomadic lifestyle that had defined his work thus far.

He was paid a wage and a stipend for supplies and services, and in 1330, Robert of Anjou referred to him as “familiaris,” which meant that he had joined the royal household.

Regrettably, very few of his artworks from this time period have survived. A portion of a fresco depicting Christ’s Lamentation in the church of Santa Chiara shows his stamp, and so does the ensemble of Illustrious Men that grace the windows of Castel Nuovo’s Santa Barbara Chapel, but academics commonly assign both works to Giotto’s students.

Shortly after his recent stay in Naples, Giotto spent a brief period in the city of Bologna, where he completed a Polyptych for the church of Santa Maria Degli Angeli and, it is thought, a long-lost decoration for Cardinal Legate’s Chapel in the castle. Giotto returned to Florence again in 1334. Giotto had become acquainted with Sacchetti and Boccaccio in his later years, and he had also been portrayed in their stories. Sacchetti related an instance in which a layman requested Giotto to create his coat of arms on a shield; Giotto rather portrayed the shield “armed to the teeth,” replete with a sword, spear, knife, and suit of armor.

He was charged after advising someone to “get into civilization for a while before you speak about weaponry like you’re the Duke of Bavaria.” Giotto filed a counterclaim and was granted two florins.

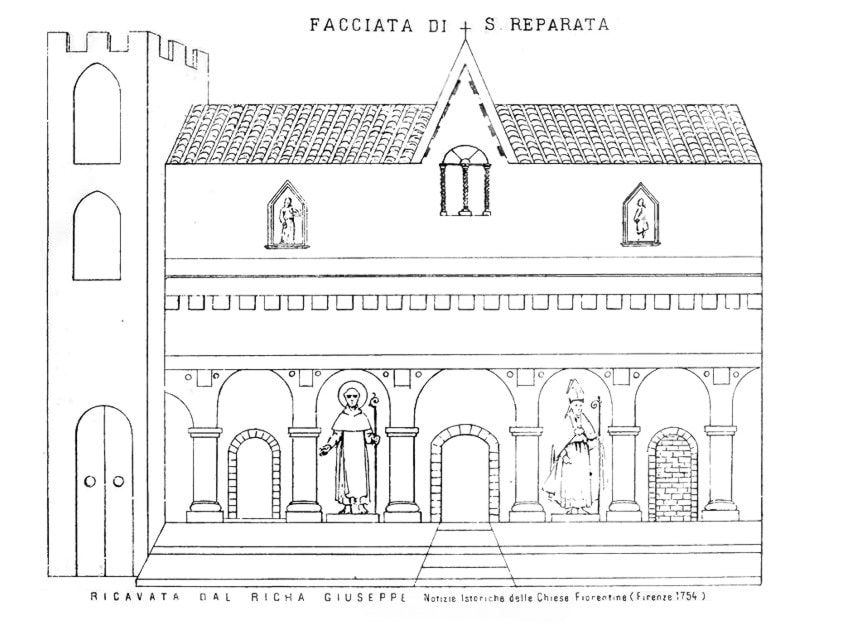

He directed the creation of art for the erection of Florence’s cathedral, and his own addition was a bell tower plan (although only the lower part of the tower was eventually constructed to his designs). The new church, which began construction at the end of the 13th century, would not be finished for another 200 years. Following his passing on the 8th of January, 1337, Giotto was apparently laid in the Santa Reparata at the expense of the city as a reflection of the reverence with which he was held. Giotto was buried in the Cathedral of Florence, on the left side of the entrance, and his burial is marked by a white marble plaque, according to Vasari. According to various stories, he was buried at the Church of Santa Reparata.

The somewhat contradictory traditions are resolved by the knowledge that the remains of Santa Reparata lay precisely beneath the Cathedral, and the church was still used in the early 14th century when the cathedral was being built.

During a 1970s excavation, bones were uncovered beneath the pavement of Santa Reparata, near the position mentioned by Vasari but unidentified on either level.

In 2000, anthropologist Francesco Mallegni and a group of specialists conducted a forensic analysis of the bones, which revealed some proof which seemed to verify that they were that of an artist – especially the variety of substances, such as arsenic and lead, both typically found in paint, which the bones had soaked up. The bones belonged to an extremely short individual, just over four feet in height, who may have had congenital dwarfism.

The Art Style and Legacy of Giotto di Bondone

Giotto had a huge impact on the formation of the Italian Renaissance and, as a result, on most of the development of European art. Giotto’s expansions of visual space and a desire for an unparalleled degree of authenticity would influence the early masterminds of the Renaissance in Florence, and he was recognized as a master in his own time by poets and intellectuals such as Dante and Boccaccio.

His impact may be observed especially in the sculptural revolution started by personalities such as Donatello and Lorenzo Ghiberti in the first ten years of the 1400s, while his artistic legacy can also be seen in the works of the young Masaccio ahead of 1420.

Giotto’s influence stems mostly from his early forays into Renaissance Humanism, a body of philosophy that would be critical to the growth of Renaissance art. Humanism entailed going to antiquity for knowledge and visual skills. This may be observed in Giotto’s work via his focus on conveying human emotions, his depiction of the human figure, and his ability to bridge the gap between biblical figures and human viewers. Giotto’s concern in design, proportion, perspective, and even engineering exemplifies his Humanism.

These were also important parts of subsequent advances in Renaissance humanist thinking and art when humans became vital to creative endeavor and the realistic representation of people and feeling became paramount. It is worth noting that there was a big gap between Giotto’s early revolutionary work about 1300 and the art revolution that occurred roughly a century later. This is most likely due to the epidemic and economic depression that occurred between Giotto’s demise and the start of the 15th century.

The plague pandemic of 1348 killed a large number of the residents of Florence, as well as places such as Siena, which had a thriving creative movement and style of its own up to this moment, but from which it never rebounded. Giotto’s achievements could not be completely appreciated and expanded upon until the comparative stability and affluence of Florence in the early 1400s.

Later painters acknowledged Giotto’s impact, and his work rekindled attention among modernists operating in the early half of the twentieth century, including individuals such as Roger Fry and Henry Moore. Giotto is recognized as being among the first prominent artists from Italy, instilled in medieval art techniques a new feeling of humanism and expressiveness.

Modern painters began to see “flat” Christian artworks as soulless and totally devoid of emotion as a result of his influence. Through his care and attention, Giotto’s “new realism” accentuated its humanity.

His three-dimensional figures were formed with gestures and movements, as well as precise clothes and furniture items. Notwithstanding their commitment to Christ, his humanistic pictures are central to his narrative. Giotto di Bondone was regarded as a highly renowned artist during his lifetime. This was partly due to the great Italian poet Dante, who labeled him the most notable Italian artist, raising him above even Cimabue (originally Giotto’s master), who had previously been recognized as the most outstanding genius of 14th-century painting in Italy.

Giotto was also a well-known architect.

He worked as a master builder on the Opera del Duomo in Florence, erecting the first phase of the Gothic (intended as much for aesthetic as utility) Bell Tower, which was called after him – Giotto’s Bell Tower. The tower is commonly regarded as Italy’s most magnificent campanile. Giotto di Bondone’s art style was influenced by Arnolfo di Cambio’s strong and classicizing sculpture.

Giotto’s figures, unlike those of Cimabue and Duccio, are neither stylized nor elongated, and they do not adhere to Byzantine models. They are substantially three-dimensional, with close-observed features and motions, and are dressed in fabrics that hang organically and have shape and weight rather than flowing structured draperies. He also experimented with foreshortening and having figures facing inward, with their backs to the observer, to create the feeling of spaciousness.

The people inhabit compacted surroundings with realistic aspects, frequently employing forced perspective tactics to simulate stage sets.

This resemblance is heightened by Giotto’s meticulous placement of the characters in such a manner that the observer seems to have a specific location and even involvement in several of the scenes. This is particularly evident in the placement of the characters in Lamentation (1306) and the Mocking of Christ (1306), in which the composition invites the observer to become a blasphemer in one and a mourner in the other.

Giotto’s Renaissance depiction of emotions and facial expressions sets his work apart from those of his peers. When the shamed Joachim returns to the hill, the two youthful shepherds exchange sidelong glances. In the Massacre of the Innocents (1305), a soldier takes a wailing infant from its mother, his head bowed into his shoulders and an expression of humiliation on his face. As they go to Egypt, the people around them talk about Mary and Joseph.

“He depicted the Madonna and the Christ and St Joseph, sure, by all means, but primarily Mother, Father, and Baby,” wrote the English critic John Ruskin of Giotto’s realism.

The Adoration of the Magi (1305), wherein a meteor-like Star of Bethlehem shoots through the sky, is one of the series’ most famous stories. Giotto is supposed to have been influenced by Halley’s comet’s 1301 appearance, which resulted in the nickname Giotto being assigned to a 1986 probe to the comet.

Giotto’s Most Influential Work

Around 1305, Giotto completed his most significant work, the interior frescoes of Padua’s Scrovegni Chapel, which was designated a UNESCO World Heritage site in 2021, along with other 14th-century fresco cycles in other structures across the city center. Enrico degli Scrovegni ordered the chapel to be used for family prayer, burial, and as the scene for an annual mystery play.

The decoration’s subject is Salvation, with a focus on the Virgin Mary, as the church is consecrated to the Annunciation and the Virgin of Charity.

The Last Judgment (1306) dominates the west wall, as was usual in medieval Italian church décor. The Annunciation is shown by contrasting artworks of the Virgin Mary and the angel Gabriel on either side of the chancel. The paintings, however, are more than just depictions of well-known passages, and academics have discovered several sources for Giotto’s interpretations of religious stories. Here are a few more famous examples of Giotto di Bondone’s art:

- Adoration of the Magi (1305)

- Lamentation (1306)

- Kiss of Judas (1306)

- The Last Judgment (1306)

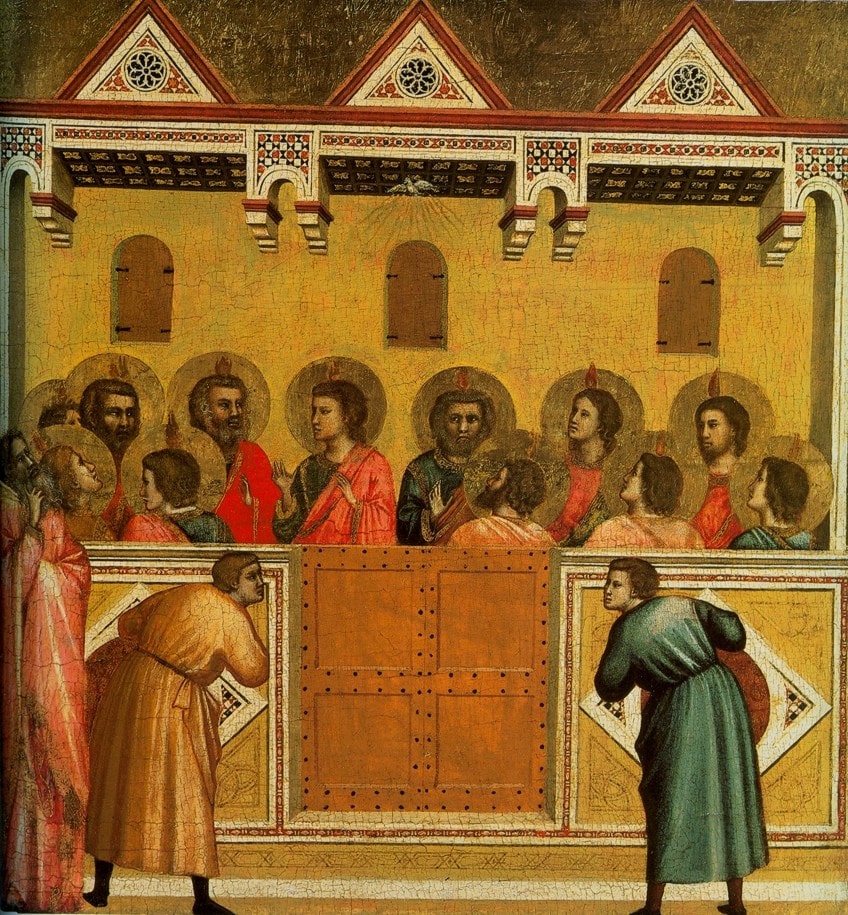

- Pentecost (1306)

- Annunciation (1306)

- Resurrection (1306)

- Madonna and Child (c. 1320-1330)

Recommended Reading

Who was Giotto and why was he famous? We have tried to cover all these questions, but perhaps you would like to discover even more about the artist in a Giotto di Bondone biography and art. Therefore, we have compiled a list of recommended books that will give you even deeper insight into the life of the painter Giotto di Bondone.

Giotto and His Publics (2011) by Julian Gardner

This in-depth examination of three Giotto works and the patrons who ordered them goes much beyond the stereotypes of Giotto the artist as the founder of Western painting. It follows the relationships among Franciscan friars and wealthy financiers, shedding light on the intricate interplay between mercantile riches and poverty imagery. Political conflict and theological schism slashed fourteenth-century Italy. Giotto’s assignments are interpreted within the context of this societal upheaval. They represented his sponsors’ requests, the Franciscan Order’s regulations, and the painter’s restless imaginative creativity.

These paintings were created during a 20-year period in which the friars were split internally and the Order was presented with a major shift in papal policy regarding its distinguishing vow of poverty. The Order had gained considerable money and constructed extravagant churches, repelling many Franciscans and earning the animosity of other Orders in the process. Many aspects in Giotto’s paintings were incorporated to appease clients, reinterpret the persona of Francis, and glorify the ruling faction within the Franciscan fraternity, incorporating links to St. Peter, Florentine economics, and church construction.

Giotto and His Works in Padua (2016) by John Ruskin

Scholars chose this work as culturally significant, and it is now part of the intellectual foundation of society as we recognize it. This work was copied from the original item and is as accurate as possible to the original. As a result, you will notice the original copyright citations, library stamps – as the majority of these publications have been stored in our most significant libraries throughout the world – and other transcriptions in the work. Scholars feel, and we agree, that this material is significant enough to be saved, duplicated, and widely distributed to the public. We appreciate your assistance in the preservation effort, and we thank you for your contribution to keeping this information alive and relevant.

- A set of reflections on Giotto's Arena Chapel fresco cycle

- A new edition that presents each work in vivid color photography

- Ekphrastic writing by John Ruskin allows readers to experience art

Delphi Complete Works of Giotto (2016) by Peter Russel

Giotto di Bondone was the prominent Artist of the 14th century, whose groundbreaking paintings would bring on to the discoveries and marvels of the High Renaissance. He is regarded as the founder of European art and the first of great Italian painters. Delphi’s Masters of Art Series introduces the world’s premier digital e-Art books, enabling consumers to thoroughly examine the works of renowned painters. This collection beautifully exhibits Giotto’s complete works, with succinct introductions, hundreds of high-quality photographs, and the typical Delphi supplementary content.

- The world's first digital e-Art book on Giotto's complete works

- With hundreds of Giotto's paintings and rare works in stunning color

- Features highlights, bonus biographies, and enlarged "detail" images

Giotto the artist is recognized as one of the most significant painters in Western art history. Giotto’s Renaissance style heralded a new era in the arts by combining spiritual antiquity with the embryonic idea of Renaissance Humanism, predating many of the fascinations and difficulties of the Italian High Renaissance by 100 years. Furthermore, many historians believe that the painter Giotto had an unequaled impact on European art until Michelangelo resumed his role 200 years later.

Frequently Asked Questions

Who Was Giotto di Bondone?

Giotto di Bondone was an artist from Italy. Giotto was perhaps the most supreme artist in his day, drawing all his models and their poses true to nature, and his ability and quality were well acknowledged. Giotto was credited with ushering in the magnificent painting and sculpture as we know it now, establishing the method of drawing precisely from life, which had been ignored for more than two hundred years.

What Is Giotto Famous For?

Giotto de Bondone was a notable 14th-century artist whose pioneering paintings paved the way for the High Renaissance’s discoveries and miracles. He is often considered the father of painting in Europe and the very first of the great painters to come from Italy. The assignments of Giotto are best understood from the perspective of this socio-economic upheaval. Giotto’s most important work, the interior paintings of Padua’s Scrovegni Chapel, was finished about 1305 and was named a UNESCO World Heritage site in 2021.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Giotto di Bondone – The Life and Art of Giotto the Renaissance Painter.” Art in Context. February 11, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/giotto-di-bondone/

Meyer, I. (2022, 11 February). Giotto di Bondone – The Life and Art of Giotto the Renaissance Painter. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/giotto-di-bondone/

Meyer, Isabella. “Giotto di Bondone – The Life and Art of Giotto the Renaissance Painter.” Art in Context, February 11, 2022. https://artincontext.org/giotto-di-bondone/.