Performance Art – A Look at the Types of Performance Art

A shift occurred in the art world when performance art got its name in the 1970s. For the first time in history, the possibility for the artist’s body to be involved in final art products became available. That being said, the first examples of performance art date back to the Futurists, Surrealists, and Dadaists of the 1910s. To track the history, rise, and development of performance art in this article, we will look at the questions, “What is performance art?” and “Is performance art really art?” We will also discuss examples of performance artworks, different types of performance art, and the work of well-known performance artists.

Performance Art

The term “performance art” is ascribed to art that involves the body of the artist or other collaborators in live or recorded action. There is often no other physical output besides the documentation of the action that took place. This non-traditional form of art allowed artists to work with the experience of live-ness and impermanence in their work. But what made artists want to create in this “new” art form and how has it developed since being recognized as a style of art in the 1970s? In this section of the article, we will look at the history of performance art.

The History and Rise of Performance Art

People have used their bodies as a means to express themselves since ancient times in dances, plays, and ritualistic ceremonies. So, what made performance become a separate art form? When looking at the history of art, it becomes clear that artists have often turned towards performance art when they need to breathe new life into their work. This is evident in the important role performance art played in avant-garde art during the 20th century in defining new ways of creating.

In this sense, the rise of performance art as a serious art movement first started as a protest against what was deemed “acceptable” art by powerful art institutions.

Avant-Garde Performances

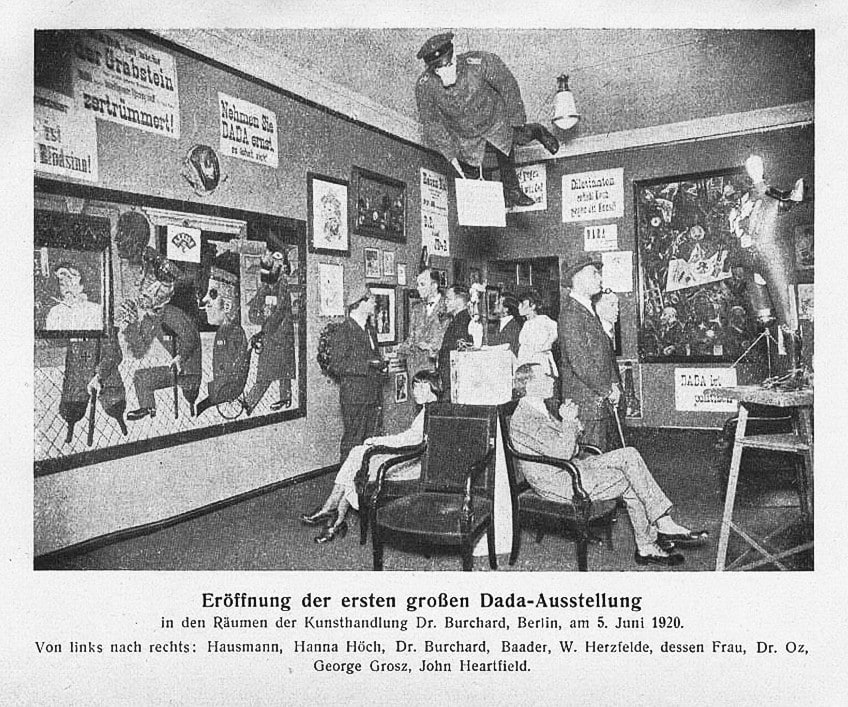

This “performance” against art institutions is characteristic of the Futurist, and Surrealist performances as well as the Dadaist’s cabaret. These art movements rose in response to the first World War and mocked the materialistic and nationalistic ideas present at that moment.

In the 1910s, these performance art pieces (not even named as such yet) were considered extremely controversial and rejected by art institutions like established galleries and museums.

These performances were often held to engage topics around the artists’ dissatisfaction with the norms of the art world. For example, the Dadaists did a performance piece that mocked the notion of rationalism, associated with the Cubist art movement at the time. Often held in theaters and private homes, these performances expressed the art movements (Dadaism, Surrealism, and Futurism) understanding of what art is and how it differs from what is deemed “good” art by established institutions.

These performances, with the purpose to destabilize norms, set the stage for what was to come.

Post-War Performance Art of the 1950s and 1960s

The next waves of performance art pieces took place after the Second World War. Although in recent years performance art engages the politics of identity, and specifics of space, and offers artists a direct way to engage with social reality, when it became more popular at the end of the 1950s and in the 1960s, it first focused entirely on the body.

Performance art was first referred to as Body Art. During the decline of Modernism and Abstract Expressionism, artists started to look at ways to make art products even more abstract.

They wanted to challenge all the normal ways in which art was understood and felt limited by the traditional art forms. The rise in popularity of performance during this time marked a move away from traditional art forms toward the further “dematerialization” of the art object. The dancer Merce Cunningham and composer John Cage largely catalyzed post-war performance art. They worked at the unconventional art institution, Black Mountain College, and encouraged their students to do performances as part of their artistic expression and research.

Their work at the institution and Cage’s instruction in New York inspired famous artists like Robert Rauschenberg, George Brecht, Yoko Ono, and Allan Kaprow. These artists banded together to start the Fluxus movement and “happenings,” which both had performances at their center. Inspired by Dadaism, “happenings” took place in all sorts of unconventional venues during the 1950s and 1960s.

This form of performance art involved the active participation of the viewer and was characterized by its improvised nature.

Some aspects of a “happening” were planned, but the audience’s participation and improvisational spirit of the event aimed to enliven a critical consciousness in the spectator and wanted to challenge the idea that art must be static or a fixed object. In the late 1950s, many European artists felt frustrated by the apolitical Abstract Expressionist Art that was widely accepted and practiced at the time. They wanted art forms that challenged the norms and communicated the social, political, and economic dissonance caused by the wars.

Performance art and specifically the Fluxus movement offered this to them. Yves Klein is considered a post-war, neo-avant-garde artist. The mix and transition from physical and traditional art forms to impermanent, movement-based art are clear in this French artist’s work. Even though his work still involved painting, he shifted the focus to the movements of the subjects he painted. The actions of the actresses he painted, who rolled around on the floor creating imprints of their bodies, became just as characteristic of his work as the intense blue hues he used.

The actions performed by the subjects became just as important, or even more so than the act of painting their bodies.

Without the movement and performance element, the work would not have been so striking at the time it was created. Another famous performance group called the Viennese Actionists consisted of mainly four artists that staged upsetting, unsettling, and taboo-breaking performances in Austria after the Second World War.

They felt that the Austrian people (specifically the Viennese) were suffering from collective amnesia after the horrors of the war or were suppressing the role they played in the terrible actions of the Nazis. Through their performances, which often involved milk, blood, urine, and entrails being smeared or thrown onto the “surface” of the body, they wanted to confront viewers with the past and the responsibility thereof.

Their extreme performances often ended in the artists being arrested, which added to their protest of governmental surveillance and not being able to speak freely.

In Japan, the first performance group that rejected traditional art forms for the medium of performance was called the Gutai. They used paint, installation, theatrical events, and performance in brand new, energetic ways. This group is now considered one of the most important cultural groups of the post-war era in Japan as they achieved international recognition and influenced many performance artists that followed them.

They focused on individualism and took advantage of the new freedoms granted to Japanese citizens after the country became a democracy. Before this moment in the country, the idea of the “national body” was pushed by an authoritarian government, which is why a big motivation and motto for this group was to “do what no one has done before”.

Feminism and Performance Art of the 1970s

In the 1960s and 1970s, second-wave feminism largely influenced female artists to turn towards performance as a confrontational medium. Yoko Ono is a good example of an artist that used her body to highlight how traditional art exploited and exposed the female body for the consumption of the male gaze. In her performance piece, Cut Pieces (1964), she invited the audience to cut the clothing off her body, making them complicit in the act of exposing her female form.

Performance pieces like this became more popular and afforded women the opportunity to create edgy engagements about their frustrations with social, economic, and political injustice as well as empowering them with a platform to have discussions about female sexuality.

The body-focused medium of performance art gave women a platform to be heard like never before on topics such as their rage, lust, sadness, and expression.

Performance art was so new that many female artists started claiming it as an all-female art form or abandoned all traditionally male-dominated mediums to focus solely on performance and the expression of issues that male artists had never done before.

Again, another war pivoted performance art to the center of the art world when artists expressed their rejections of the United States’ imperialism and political agendas connected to the Vietnam War.

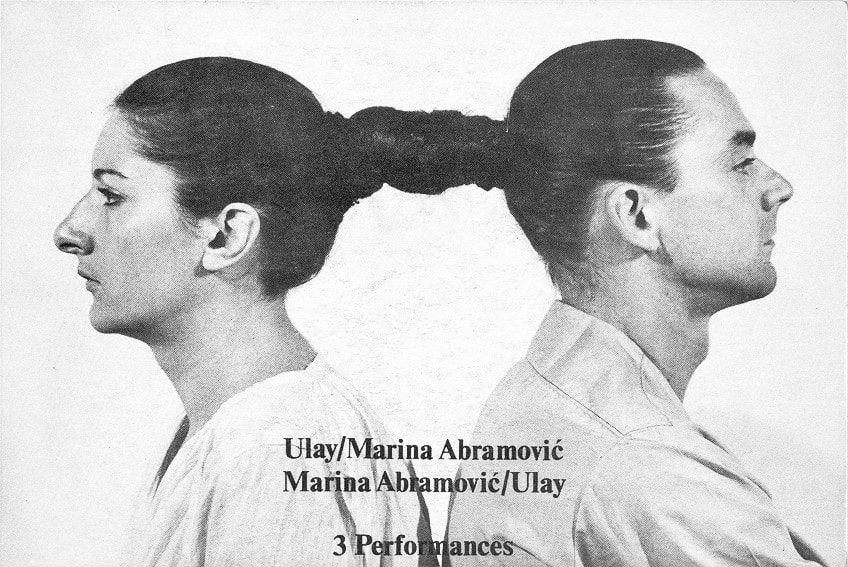

Artists like Chris Burden and Joseph Beuys, who both created work in the 1970s, started pushing the limits of the body even further. Their art was often upsetting and involved straining the body to its limits. The term Endurance Art became associated with artists practicing at this time as well as, for example, the art couple Marina Abramović and Ulay. The Neoconcretist movement in Latin America was also known for its performance art during this time.

Performance Art of the 1980s

In the 1980s, the economic doom led to a rise in buyers and collectors wanting material art pieces to trade. This brought traditional art forms like painting, drawing, and sculpture back into focus. Performance art fell from its prominence as it dealt with uncomfortable topics and its most impactful form centered on the live-ness of the pieces.

However, female artists continued to use this newly claimed art form as a medium to express their experience of oppression, femininity, and sexuality.

The American artist Laurie Anderson became famous for her dramatic multimedia performances about the period’s social issues during this era. One of her performance pieces from this time, United States I-IV (1983), consisted of projected drawings, text, photography, film, and music. The performance was recorded as a 5-LP album and looked at the themes of transportation, politics, money, and love.

Performance Art of the 1990s

As in the past, performance art started thriving again in the 1990s as artists started engaging in new issues such as queer identity, the AIDS crisis, and immigration. Western countries began to celebrate multiculturalism which led to artists such as Guillermo Gomez-Pena and Tania Bruguera rising to fame. Latin American performance art was celebrated at international biennales and competitions. These artists showcased performance work at international biennales relating to topics such as oppression, poverty, and immigration in Mexico and Cuba.

These issues often caused controversy and specifically, artworks that dealt with queerness and AIDS were at the center of the 1990s Culture Wars.

Tim Miller, John Fleck, Karen Finley, and Holly Hughes famously passed the peer review board to get funding from the National Endowment for the Arts. Their successful application was then rejected after the theme, sexuality, was made public.

This caused an uproar in the artist community and again solidified performance art as a form of protest.

Although it started as a protest against art institutions, performance art is nowadays widely accepted by most museums, galleries, biennales, competitions, and foundations. It is still a medium often used in combination with other mediums such as paint, installation, and drawing, but now also involves new technology like projection, animation, and sustainable art.

Different Types of Performance Art

Performance art always involves the body of the artist or other people the artist has commissioned to help with producing the piece. It can take place live, in public, or be a recorded experience that took place in a private setting or closed gallery. Often, performance art involves other mediums and objects, but the main focus is the action that takes place by the performer. Let’s look at different types of performance art.

Action

The category “action” is one of the first types of modern performance art. The name aimed to set this kind of art apart from traditional art forms as well as distinguish it from the theater, plays, or music performances. It also shows how artists thought of the work they produced as this term was used, for example, by action painters in the 1950s to highlight the meeting of the painter with the painting.

The action of painting, therefore, became a kind of performance that added to the final painted artwork.

Other artists used the term for the open-ended experience it implied- meaning that any kind of action could be viewed as an artwork/performance piece. Artists like Yoko Ono used this type of performance art to do conceptual experiments where she invited the audience to choose an action from a list she compiled and act it out.

Body Art

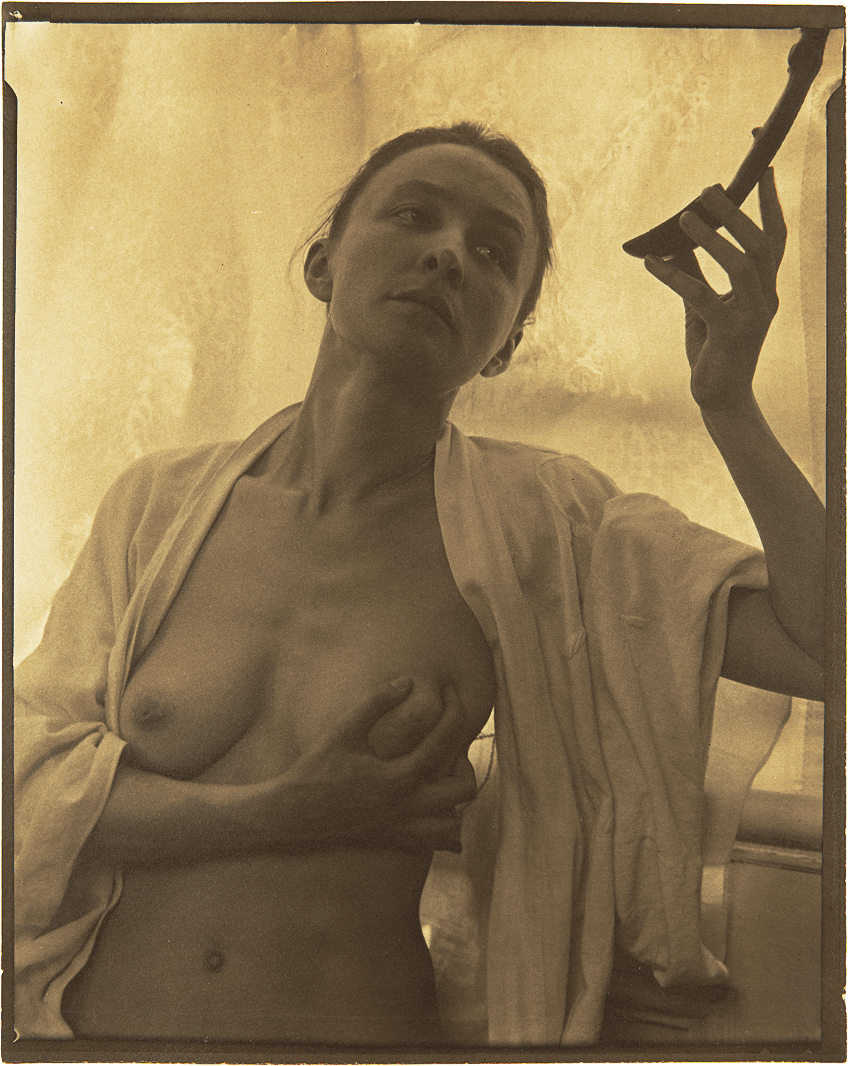

Body art placed the body of the performer at the center of the art piece. The body became the medium, subject, and surface where the artwork took place. This put an emphasis on first-person experience and brought the artist even more to the center of the work created. The political persona came more into focus post-1960s as the social atmosphere was changing and taboos around nudity were being challenged by artists.

Body art was specifically used by feminist artists like Carolee Schneemann, VALIE EXPORT, and Hannah Wilke who used their bodies to challenge the traditional way the female experience and body were portrayed in the media and by male-dominated art forms.

Other artists used their bodies to question their relationship with the world at large. Acts of self-inflicted violence on the artist’s body were used by artists like Marina Abramović, Gina Pane, and Chris Burden in performances to confront the audience with their involvement as voyeurs.

Happenings

As discussed in the previous section, “happenings” became a famous type of performance art during the 1960s. It centered around the involvement of the audience and for the first time brought improvisation into the act of performance. The idea that anything could happen during these performances and that what took place might never be repeated exactly again was characteristic of these events.

This resulted in a hyper-aware audience that was collaborators from start to finish of the happening.

Endurance

Most of the above-mentioned movements were absorbed as characteristics of contemporary performance art, but Endurance art became such a famous sub-section of performance art that it earned its own name that is still being used today. Endurance performance involves the artist or performer putting their body under strain or pain to communicate the message of the work. The importance of endurance in making performance art the art form it is today is evident in the kinds of themes addressed by performance artists during the post-war era.

Performance artists in the 1950s and 1960s believed that the body is the only way through which the reality of experience can be communicated by the artist.

Since what they wanted to communicate was the upsetting and violent truth of the post-war experience, it makes sense that putting the body under strain became a popular element of performance art. Endurance art pieces often spoke about themes like violence, oppression, freedom of speech, female power, and so on.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0MKA_04bEnY&t=51s

These artworks are characteristically difficult to view and aim to use the pain or fatigue of the artist performing to highlight the lived experience of these themes. Even though these artworks often look like abuse, they are less about exploring what the artist can survive and more focused on patience, determination, and tenacity.

Endurance art often also aims to blend art and everyday life, making the artwork so long that it can almost not be considered separate from the artist’s lived experience.

One of the most influential artists in this type of performance is the Taiwanese artist Tehching Hsieh. He performed multiple one-year pieces during his career, including the first called, Cage Piece (1978-1979). In this performance, he locked himself in a cage in his New York studio. He was not allowed to consume any media during this time, commenting on consumption, surveillance, governmental power, discipline, and submission.

Ritual

Ritual means to perform a specific set of actions in a way prescribed by religion, group, or institution. However, ritual is often a very important part of performance artworks. In this instance, the artist is the one deciding which actions will be performed, how they will be performed and how they will be repeated to create the feeling of ritual or ceremony.

It can be a characteristic of a performance piece, but some artists use it as the main component of the work they perform.

For example, Marina Abramović (her work is discussed in more depth below) uses ritual in most of her work, making it feel quasi-religious. This inclusion of ritual shows that although the performance art movement started with the purpose to demystify art, some artists have used rituals to re-mystify it through performance. So, instead of bringing art closer to everyday life, the use of ritual reintroduces a sense of sacredness in the artmaking and viewing process.

Famous Performance Artists and Examples of Their Work

Performance artists that practiced during the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s were pioneers in this medium that was never used so seriously before. There was so much to discover and explore, as examples of performance art were few. Some of these artists are still highly acclaimed by the art world. In this section, we will look at two such pioneering creatives: Marina Abramović and Joseph Beuys.

Joseph Beuys (1921 – 1986)

| Date of Birth | May 12, 1921 |

| Date of Death | January 23, 1986 |

| Country of Birth | Germany |

| Associated Art Movements | Fluxus |

| Genre/Style | Conceptual Art, Performance Art |

| Mediums Used | Drawing, painting, sculpture, process-oriented and time-based “action” art, performance |

| Dominant Themes | The personal, psychology, social issues, politics, reality, fact, and fiction |

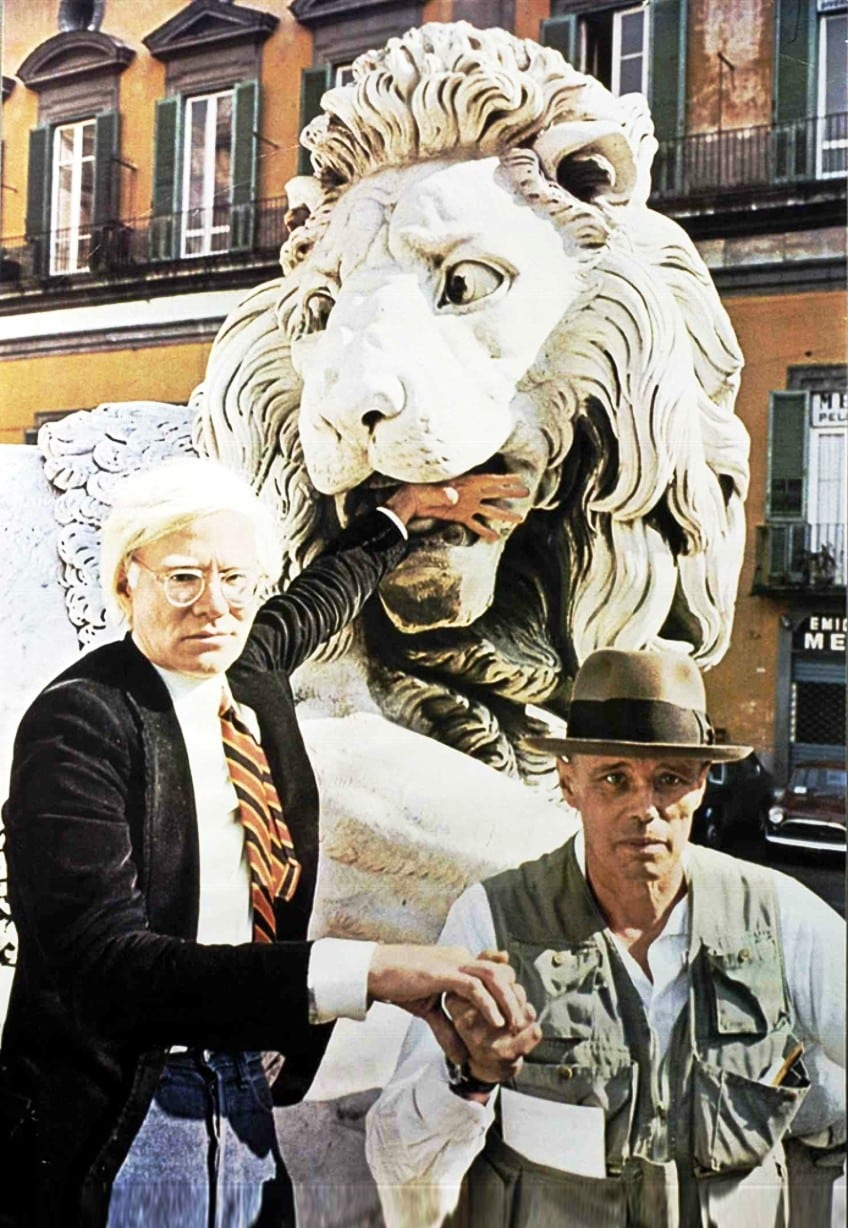

Joseph Beuys, known for art pieces that often involved animal fat and felt, created work exploring the line (or lack thereof) between art, everyday objects, and everyday life. He was an important artist in the Fluxus movement during the 1960s and had a big influence on the rise and development of performance art.

He was one of the first artists that turned away from what the consumer wanted from art to use found and everyday objects in experimental “happenings”. These performance events were time-based, action-based, and ephemeral.

Over three decades (from the 1950s to the 1980s), Beuys was interested in exploring how art can begin and be expressed in the personal realm and still say something about the current social and political issues. This idea informed his teachings and works to such an extent that it became a life philosophy for him- that being, art as a way of life and not simply as a profession or hobby. This philosophy went so far as to claim that what one believes to be reality is more important to societal issues than any larger definition of what reality means based on traditional norms and standards.

In a prominent example of a performance art piece by Beuys titled, How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare (1965), the artist was viewed sitting on a chair through a gallery window. His face was covered with honey and gold leaf, an iron slab tied to one boot, and a piece of felt to the other boot. He cradled a dead hare in his lap and whispered things about his drawings hanging on the walls to the carcass of the animal. Now and again he would get up and pace around the tight space, the one step loudened by the iron and the other muted by the felt.

This very symbolic piece centered on the everyday connotation and symbolic understanding of the elements used.

For example, the honey symbolized life, the gold as wealth, the hare as death, the metal as a conductor of invisible energies, and the felt as protection. By creating this performance piece, Beuys created a symbolic performance structure for other artists to follow him. At the end of his life, Beuys’ work became more political and he founded many political organizations. He became very ill and died of heart failure at the age of 65.

A piece he started for the Documenta 7 exhibition in 1982 called 7000 Oak was continued after his life by supporters of his work. Beuys proposed to plant 7000 oak trees in the city of Kassel, each tree accompanied by basalt stone. The project took five years to complete and was carried out in other countries in the world as well, communicating the impact and presence of the artist after his death.

Marina Abramović (1946 – Present)

| Date of Birth | November 30, 1946 |

| Date of Death | N/A |

| Country of Birth | Yugoslavia |

| Associated Art Movements | Performance art |

| Genre/Style | Body art, Endurance art, Conceptual art |

| Mediums Used | Performance, installation, audience engagement |

| Dominant Themes | Self, the relationship between subject and object, limits of the body, consciousness, the responsibility and resistance of the audience, violence, politics, death, and life |

Marina Abramović has been practicing performance art for over four decades. She has used her body as a site for experimentation, expression, and controversy. Abramović’s work is known for the experiments she conducts through her performances on the control one has over one’s body.

Through her performances, which are often long meditations on this subject, she tries to identify and push the limits of control over her body. In her performances, the audience is often directly involved.

Here is where she explores the relationship between subject and object, stretching the traditional classification of things in art history. By making herself the subject and medium of her work, Abramović expands the normal understanding of aesthetics and any art piece. Abramović debuted her career with the famous performance series Rhythm (1973/74) and from the get-go, shocked the world with daring, provocative, and transgressive pieces. This series was created after the Serbian artist complete her studies and started teaching Fine Art in Serbia.

Before the first performance, Rhythm 10 (1973), in the series Rhythm, Abramović’s work used mainly sound as a medium. Rhythm 10 (1973) constituted a shift in her work to use performance and importantly, the audience’s reaction and energy in watching her perform as a means of exploring the limitations of her body and consciousness. In the work Rhythm 10 (1973), she used 20 knives to rhythmically stab the spaces between her spread-out fingers. Every time she stabbed her hand during the performance she changed to a different knife.

Halfway through the performance, she played the sound of the first half an hour of stabbing to redo the actions performed on the rhythm of the sound she recorded. She reused the same knives and stabbed herself again in the same places. Here, the audience’s resistance to watching her perform self-harming actions became important and later would be a key to new work created.

Abramović also explores the limits of consciousness as she often enters states of meditation during her pieces and drugs herself to push the limits of her body even further.

Rhythm 5 (1974) was such a piece where after lighting wood chips, nails, and hair clippings in the shape of a star she lay down in the burning star and lost consciousness due to the lack of oxygen. This piece, symbolizing the occult and Communism in Yugoslavia, was stopped by audience members dragging her unconscious body out of the fire as her clothes started burning. Abramović’s work is also associated with the work she created with German artist, Frank Uwe Laysiepen, also known as Ulay.

The artists were lovers and collaborators from 1975 until 1988 and created powerful and unsettling performances together. After their separation, ending with the performance piece The Lover’s (1988) where the two artists walked for three months from separate sides of the Great Wall of China to meet in the middle to say goodbye, they did not see each other for many years. They met again in person for the first time since their separation during a solo piece titled, The Artist is Present (2010).

For the full duration of her solo exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, Abramović sat across an empty chair in which viewers were invited to sit for any amount of time. Abramović would close her eyes between participants and open them each time someone sat down to look at them for as long as they stayed seated.

Ulay sat down in front of her and when Abramović opened her eyes she started crying and reached out to hold his hands, breaking her performance rules, which, she said later, she had never done before or since.

Abramović refers to herself as the “grandmother of performance art”, which accurately captures this artist’s influence and contribution to the medium and movement of performance. She was one of the first artists to experiment with performance and body art and is still teaching and creating new work.

Performance art brought about one of the biggest shifts in the history of art. When the focus shifted from the art object to the body and action of the performer, it opened the gates to the contemporary art moment we have arrived at today. Besides marking a shift in artists from complying with harsh standards of art institutions, the rise of performance art also went parallel with a financial shift in the art market. After the World Wars, power and money shifted in the world, and artists were left to fend for themselves. These shifts and the results thereof are evident in the contemporary idea that anything – really anything – can be art. Without clear boundaries around what constitutes an art piece, there is no way to truly uphold standards by which art pieces are deemed successful and desirable. Nowadays, an artist can be “discovered” simply by being at the right time and place to catch an art investor’s eyes. Where we are now is a brand-new place in art history and performance art arose when it all started to change.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is Performance Art?

Performance art refers to an action or actions performed by an artist and/or other collaborators. It is often performed live, which gives the artwork an impermanent nature. However, there are many examples of performance art pieces that have been recorded and screened after the live event has passed. Besides a potential recording, performance art often has no other tangible products.

What Different Types of Performance Art Are There?

Contemporary performance art involves various kinds of mediums and expressions. These performances are not often categorized into different types of performance art but are just broadly termed as performance or multimedia art. However, when performance art started becoming more popular and was still practiced in resistance to traditional art institutions, four types of performance art emerged: action, happenings, ritual, and endurance.

Is Performance Art Really Art?

The question of whether performance art is really art has puzzled art critics and viewers for decades. The ephemeral nature of performance art was echoed in 2016 by theorist Jonah Westerman, who said that performance art is not or ever was a medium. He explained that it is not something that an artwork can be but rather a list of questions about how art links to people and the world at large. However, it all depends on how you define art. If art is defined as a tangible product produced and viewed separately from the artist, then performance art is not art. If art is defined as anything an artist calls art, then performance art is art. That being said, large and powerful institutions in the art world nowadays widely accept performance art as a legit art form and it is therefore displayed and commodified like any other medium of art.

Nicolene Burger is a South African multi-media artist, working primarily in oil paint and performance art. She received her BA (Visual Arts) from Stellenbosch University in 2017. In 2018, Burger showed in Masan, South Korea as part of the Rhizome Artist Residency. She was selected to take part in the 2019 ICA Live Art Workshop, receiving training from art experts all around the world. In 2019 Burger opened her first solo exhibition of paintings titled, Painted Mantras, at GUS Gallery and facilitated a group collaboration project titled, Take Flight, selected to be part of Infecting the City Live Art Festival. At the moment, Nicolene is completing a practice-based master’s degree in Theatre and Performance at the University of Cape Town.

In 2020, Nicolene created a series of ZOOM performances with Lumkile Mzayiya called, Evoked?. These performances led her to create exclusive performances from her home in 2021 to accommodate the mid-pandemic audience. She also started focusing more on the sustainability of creative practices in the last 3 years and now offers creative coaching sessions to artists of all kinds. By sharing what she has learned from a 10-year practice, Burger hopes to relay more directly the sense of vulnerability with which she makes art and the core belief to her practice: Art is an immensely important and powerful bridge of communication that can offer understanding, healing and connection.

Nicolene writes our blog posts on art history with an emphasis on renowned artists and contemporary art. She also writes in the field of art industry. Her extensive artistic background and her studies in Fine and Studio Arts contribute to her expertise in the field.

Learn more about Nicolene Burger and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Nicolene, Burger, “Performance Art – A Look at the Types of Performance Art.” Art in Context. September 1, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/performance-art/

Burger, N. (2022, 1 September). Performance Art – A Look at the Types of Performance Art. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/performance-art/

Burger, Nicolene. “Performance Art – A Look at the Types of Performance Art.” Art in Context, September 1, 2022. https://artincontext.org/performance-art/.