Kinetic Art – An Overview of this Moving Art Term

Kinetic art, or art that incorporates movement, has been a steadily growing practice in the art world. Technological advances and the growing importance of machinery in the modern world were the inspiration for many artists, including the Kinetic pioneer Naum Gabo. From moving sculptures to static visual illusions, the Kinetic art movement is expansive.

What is Kinetic Art?

Broadly, any piece of art that revolves around a fascination with movement can be considered Kinetic art. Kinetic artists offer us an artistic expression of the growing modern age with its technological intersections and philosophies. Kinetic artists explored art that could extend into both space and time and artworks that morphed with viewer interaction. Mechanized sculptures that change their appearance over a cycle of time seem to capture the fast-paced evolution of the modern age.

While some Kinetic artists focused on the conflation of science and mechanization, others created works that explore mechanized movement, and others still used Kinetic art as a representation of utopian possibilities whereby modern life relies on the integration of machine and man. Some artists took the integration of man and machine even further, using their art to explore correlations between biological human bodies and the gears and pistons of metal machines.

While today, the term Kinetic art is most often associated with three-dimensional works that either move naturally or as a result of machine operation, it originated from the paintings of Impressionist artists like Edgar Degas and Claude Monet. These 19th-century Impressionist painters accentuated the movement of figures, the ocean, and light. Other early canvas-based Kinetic artworks include those that stretch the viewer’s perspective, incorporating multi-dimensional movement.

Some kinetic artworks explore virtual movement, whereby you can only perceive movement from a particular angle.

The term “apparent movement” is often confused with virtual pieces, but it refers to motion in an artwork, which is powered by mechanical or electrical motors or machines. Both the virtual and apparent Kinetic styles share similarities with Op Art, which plays with optical illusion. Victor Vasarely is one of the most well-known artists of the Op Art movement, with many of his Op Art paintings creating the impression of movement. This overlap, however, is not so extensive that these forms of Kinetic art and Op art should be categorized under a single umbrella term.

The golden age of Kinetic art was around the middle of the 20th century. Artists like Naum Gabo and Alexander Calder began to create art that was truly dynamic and three-dimensional. Each artist brought their own take on Kinetic art, and as such, we cannot define the movement as a single style or form.

The Development of the Kinetic Art Movement

As you can see from the brief introduction above, there are multiple facets to the Kinetic Art Movement of the late 19th and 20th centuries. In this next section, we are going to cover each of the prominent eras, to provide a Kinetic art definition. Taking an in-depth dive into the key ideas and pioneering artists of each movement, we hope to provide you with a well-rounded understanding of this 20th-century movement. The timeline is messy, and you will notice that theories about Kinetic rhythm in art developed in different locations at different times.

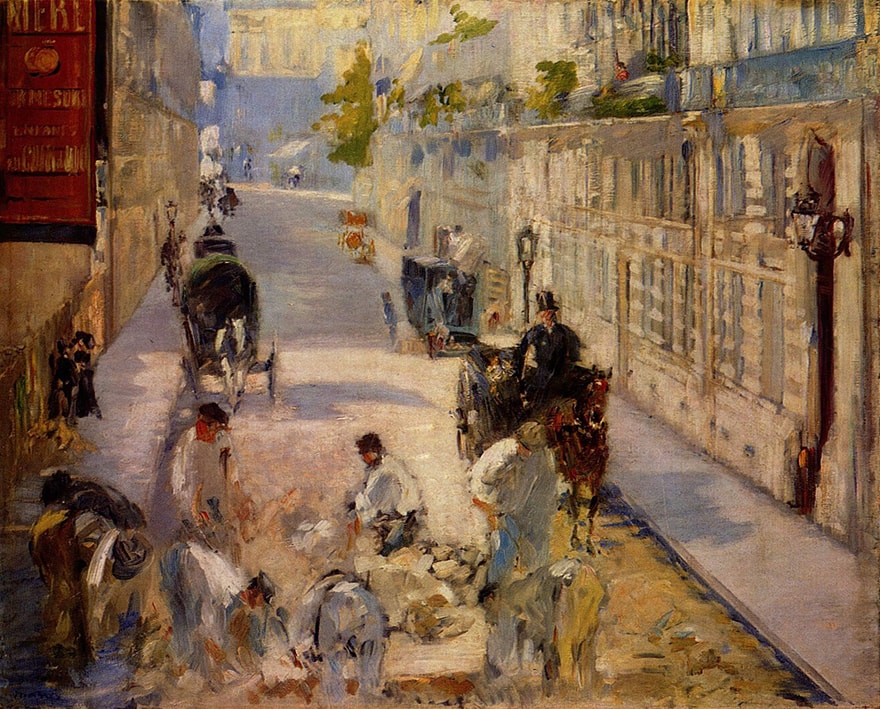

Impressionism: Capturing Movement in Paint

Three of the most prominent Impressionist painters in the 19th century made great strides in capturing the ebbs and flows of life in their art. Monet, Degas, and Edouard Manet were pioneers of the changes in compositional style and innovations in painting technique which allowed artists to capture movement more realistically. Another significant pioneer of Kinetic art during the late 19th century was Auguste Rodin. Rodin used slightly different techniques to capture the movement of the world around him.

Rodin criticized the other three Impressionists, claiming that they could not represent the vitality and temporality of motion.

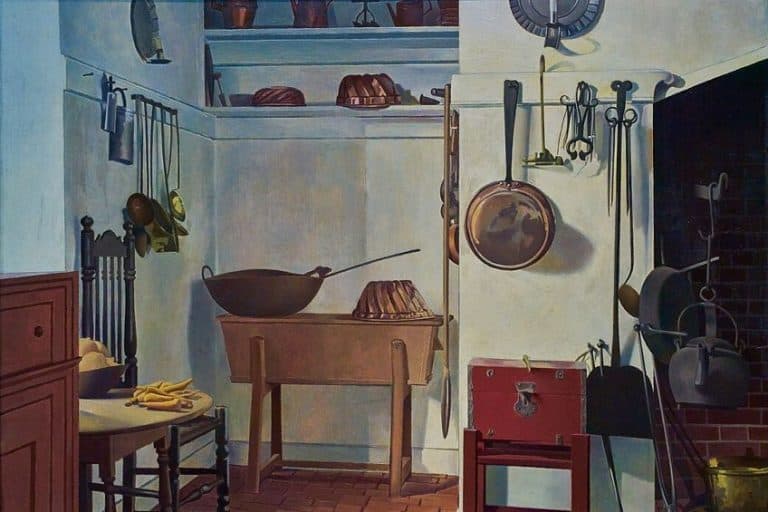

Edouard Manet (1832-1883)

Although Manet is considered by many to be an Impressionist painter, it is almost impossible to ascribe a single style to his works of art. One important theme that permeates each expression of his style is that of movement. Perhaps, his most famous painting when considering motion is Le Ballet Espagnol (1862).

In this painting, Manet matches the figure’s gestures with the contours, creating a sense of three-dimensional depth. The depth within each figure extends between them in the composition. One of the most striking ways that Manet manages to capture movement in this piece is by creating a sense of dis-equilibrium. Viewing this painting, we feel as though we are on the edge of a moment that is moments away from passing by. The viewer finds themselves in a fleeting moment, highlighted by the hazy sense of shadow and color.

A year later, Manet continued his study of motion with Le dejeuner sur l’herbe, a painting that captures a picnic in a park. The woman in the background is not scaled correctly for her position in the composition. The lack of accurate spacing within this composition creates an almost invasive snapshot of a moment of motion.

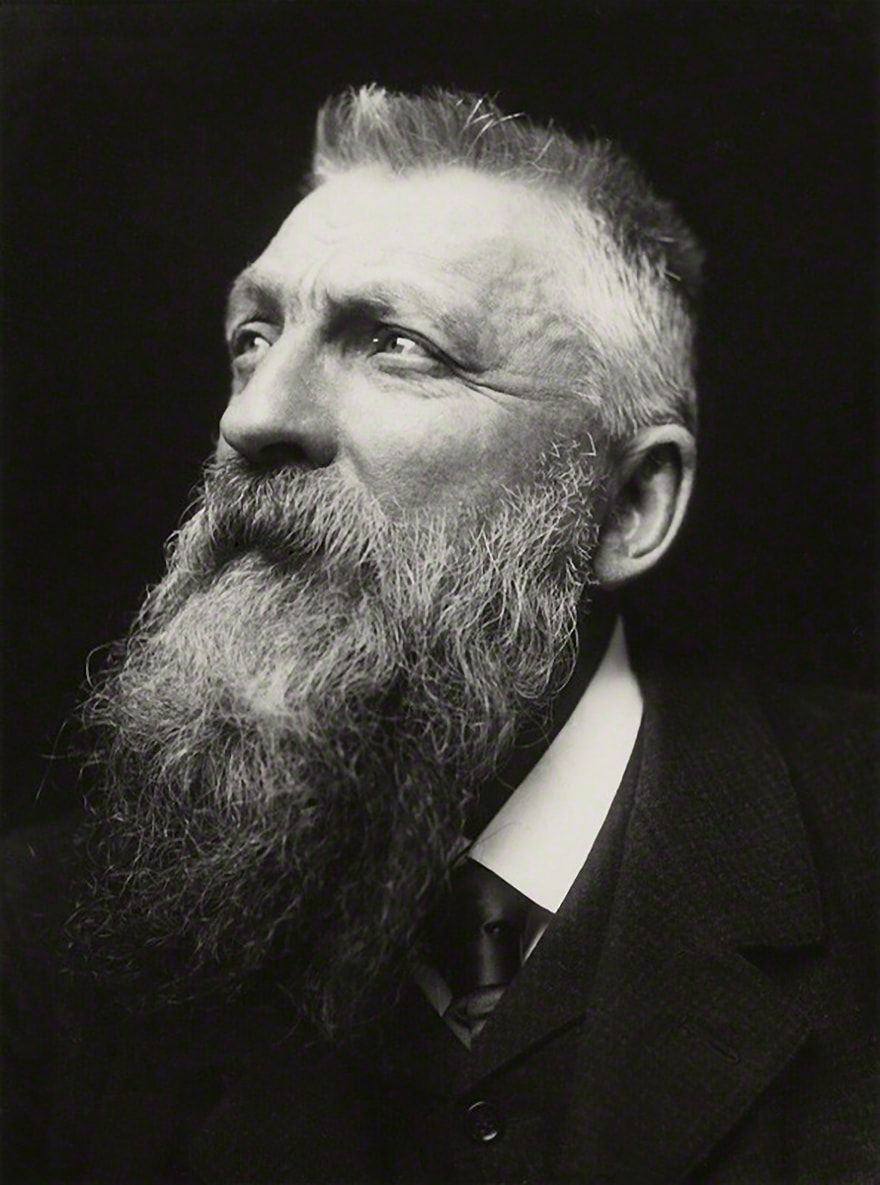

Claude Monet (1840-1926)

Monet is one of the most prominent Impressionist painters, and his paintings capture changes in light in an incredibly realistic way. Monet based his paintings on an artistic interpretation of a retinal impression, the pattern of light that hits the retina in a moment. This method of painting translates into images that capture the minute shifts in light and color. In this way, Monet’s paintings capture the world in motion, on the brink of change.

Towards the end of the 1870s, Monet began to craft a new, swifter style of painting.

The inexact brushstrokes in his 1875 Le Bateau-Atelier sur la Seine bring the landscape and figures together in motion. It was this painting, among others, that demonstrates how Monet was redefining the Impressionist style. The isolation of light, color, and movement defined the early Impressionist painting style. Monet began to craft a distinct style that combined all of these and focuses on the traditional Impressionist subjects. These paintings seem to vibrate with the motion of the world they capture.

Edgar Degas (1834-1917)

Many art historians believe that Degas’ work is an intellectual augmentation of the work of Manet. Degas had quite a radical style for the Impressionist era. Although his subjects are typical of the Impressionist style, including horses and ballet dancers, he never let the subjects outshine his attempts to capture motion in his paint. For example, in Jeunes Spartiates s’exercant a la lutte (1860), Degas presents the classic nude but places the dramatically postured figures within a flat, two-dimensional landscape. This juxtaposition emphasizes the movement of the figures.

In one of his most controversial paintings, Degas presents a unique interpretation of various movements, bringing multidimensionality to the flat canvas. The orchestra in L’Orchestre de l’Opera (1868) is positioned in the center of the viewer’s vision, and the dancers saturate the background. Once again, the juxtaposition of two subject groups steeped in different movements creates a sense of motion within the composition.

Degas’ attempts to paint dynamic motion finally began to come to fruition towards the end of the 19th century. A particularly good example is Chevaux de Course (1884), a painting from a series that depicts a moment of deliberation between horse and rider. The Impressionist community was highly impressed with this series but became horrified when they learned he used photographs as references. Degas was unphased by this response, and his continued use of this method inspired Monet to use similar techniques.

Auguste Rodin (1840-1917)

Initially, Rodin expressed his appreciation for the vibrating effect and spatial awareness that Monet and Degas managed to capture in their paintings. Rodin was both an artist and critic, and he wrote and published numerous reviews praising the Impressionist style. In these works, Rodin claimed that Degas and Monet could create an illusion of art, that through modeling and movement, captured the motion of life.

These sentiments did not carry into Rodin’s own work, however.

When he began to sculpt, he also began to question how an artist could capture life’s motion in such a stagnant medium as sculpture. Although his later articles did not attack Impressionist artists like Degas and Monet directly, he disseminated his new theories that Impressionism could not communicate movement. Instead, Rodin claimed that Impressionism simply depicted motion in a static form.

Early Kinetic Art and 20th-Century Surrealism

The loose boundaries and explorative nature of 20th-century Surrealism made for an easy transition into Kinetic art. Although the artists who created during this era incorporated motion, the formal Kinetic Movement was still in its infancy. What these artists do demonstrate is the global movement towards the inclusion of kinetic rhythms in art.

Surrealism saw artists exploring subjects and techniques that would have previously been socially unacceptable.

Going beyond depicting historical events, landscapes, and other traditional subjects artists began to find new meaning and style in the mundane. It was these oddities and deviations from the tradition that made for the first focal points of Kinetic art. Pioneered by artists like Jackson Pollock, Albert Gleizes, and Max Bill, Kinetic art began to take off in the early 20th century.

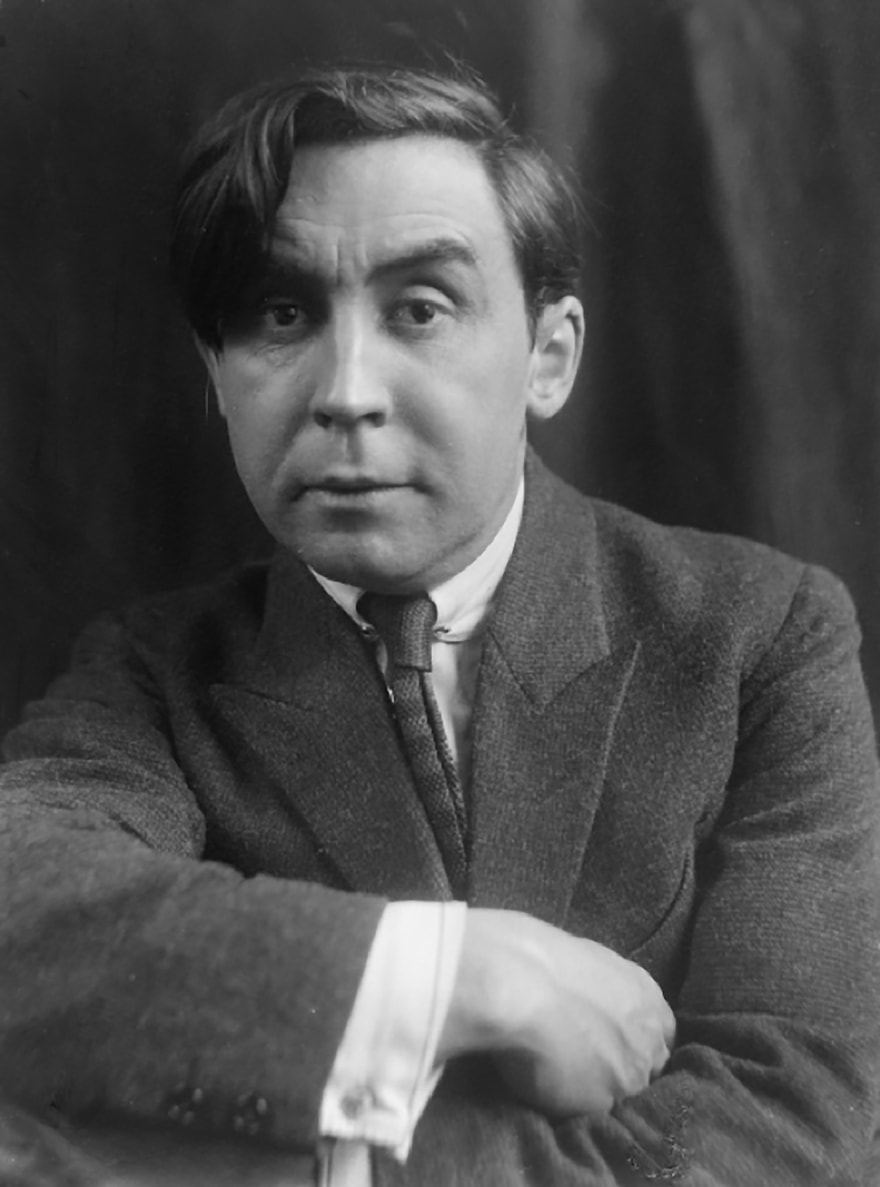

Albert Gleizes (1881-1953)

In the late 19th and early 20th century, Gleizes was one of the most prominent art philosophers. With a basis in Cubism, his treatises and theories propelled him to the center of artistic discussion. In the 1910s and 1920s, Gleizes began to support a more rhythmic art movement, instead of the more plastic traditional style. Gleizes’ notoriety helped to bolster these opinions. Around this time, Gleizes published a theory on motion in art, building on his theories on the artistic use and psychological effects of moving art. According to Gleizes, the complete renunciation of external sensation is implied by human creativity. For Gleizes, it was this fact that made art mobile, while others believed it to be rigid and static.

One of Gleizes’ primary theories stated the necessity for art to have rhythm. Rhythm in art, for Gleizes, translated into the coinciding of figures within a three or two-dimensional space in a visually appealing way. A mathematical precision should underlie the placement of various figures within the composition so that they appeared to interact with one another. The features of these figures should also be a little vague, so their movement within the canvas space is believable to the viewer. Throughout the 1930s, as Kinetic art grew in popularity, Gleizes studied the concept of artistic motion in relation to the viewer and updated his publications and studies.

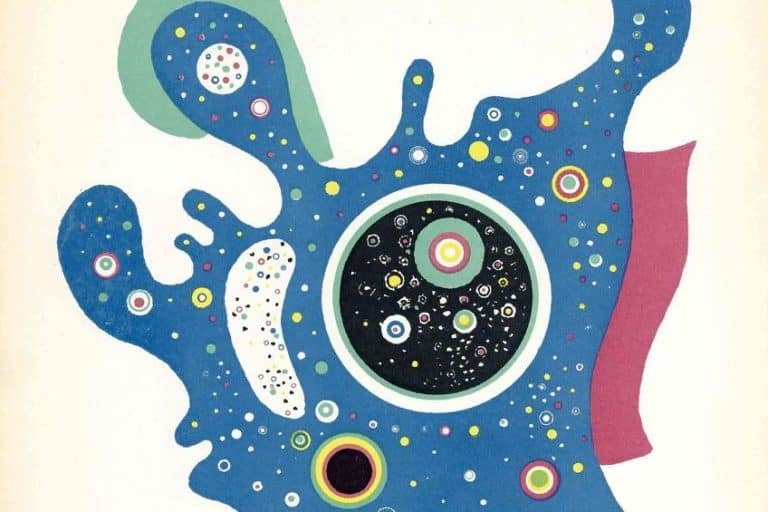

Jackson Pollock (1912-1956)

It may be surprising to find Pollock in this article because his works are not the mobiles and sculptures typically associated with the Kinetic Movement. In many ways, however, his work was at the forefront of the desire to represent motion through art. In terms of Kinetic painters, Pollock is the unrivaled leader. The new painting methods and styles that Pollock developed, allowed him to go one step further than the Impressionist artists. While Monet and Degas could capture the movement of figures and landscapes in a captivating way, Pollock was able to create motion in abstraction.

Pollock’s work is often associated with Action Painting, a term coined in the 1950s by the critic Harold Rosenberg. Pollock had the desire to create animation in every aspect of his paintings, using unconventional tools like knives and sticks. This style of painting eventually evolved into his famous drip technique. Not only is motion uniquely involved in the creative process of Pollock’s drip paintings, but it is also undeniably clear in the final piece.

Max Bill (1908-1994)

During the 1930s, Bill became a devoted disciple of the Kinetic art movement. For Bill, the beauty of Kinetic art lay in the purely mathematical precision that underlay it. Bill used mathematical understandings and principles to create objective motion within his artwork. He applied this theory to all of his sculptures in marble, brass, copper, and bronze.

Bill also loved to include a little visual illusion in his sculptures. Construction with Suspended Cube (1936), for example, is a mobile sculpture that appears to be perfectly symmetrical from one angle, but as soon as the viewer moves around the sculpture, the symmetry begins to unravel.

Constructing the Kinetic Art Movement: Sculptures and Mobiles

The Kinetic art movement was officially born with the 1920 Realistic Manifesto by Antoine Pevsner and Naum Gabo. The manifesto stated that:

“We repudiate: the millennial error inherited from Egyptian art: static rhythms seem as the sole elements of plastic creation. We proclaim a new element in plastic arts: the kinetic rhythms, which are essential forms of our perception of real time.”

According to Gabo and Pevsner, for art to be a true representation of the world we experience, we have to present it as realistically as possible. To make artistic representations as realistic as possible, artists should include perceptions of light, color, form, and importantly, movement. Failing to consider the kinetic motions of our experiences is to create an incomplete depiction.

Gabo and Pevsner were inspired to move back to Russia following the revolution, and in this context, they became closely associated with Constructivism. As a result, their early explorations of Kinetic art were highly influenced by elements of Constructivist art, including principles from architecture and engineering about functionality and growing mechanical technologies. The devotion to a realistic depiction of the world is in line with Constructivist theories about functionality, technological development, and scientific exploration.

Naum Gabo (1890-1977)

Many credit Gabo with lighting the spark of the Kinetic art movement in the early 20th century. Following his return to Russia with his brother, Antoine Pevsner, he became increasingly involved in Suprematism and Constructivism. Both of these art movements sought to blur the lines between functional technology and artistic creations. We can see the Constructivist principles in many of Gabo’s sculptures which explore new technological and scientific advances and are often methodical and matter-of-fact.

For Gabo and other Marxist Constructivists of the time, art should have a functionally explicit social value.

One of Gabo’s most influential discoveries and contributions to Kinetic sculpture was his use of empty space. Rather than carving or molding his installations from blocks of material, Gabo used interlocking but separate components. This technique allowed Gabo to incorporate space in his sculptures with more ease, and the contrast between form and void was a central part of his work. Using interlocking components also allowed Gabo to create dynamic sculptures that sometimes included moving parts or static elements that appeared to move. Standing wave is one such work that creates a physical impression of movement.

Gabo’s Kinetic sculptures stand at the doorway to the Kinetic art movement. His ideas concerning functionality, technological advancement, and motion permeate the Kinetic movement. Gabo’s first Kinetic sculpture is widely considered the first piece of the Kinetic movement. Kinetic Construction (1920) is a metal and wood sculpture with an electric motor, and it went on to influence many other Kinetic artists, including Man Ray, Vladimir Tatlin, and Alexander Rodchenko.

Vladimir Tatlin (1885-1953)

Another central figure in the growing Russian Constructivist movement, Tatlin is renowned for his sculptural creations that combine aspects of Futurism and lessons from the Synthetic and Analytic Cubism of Picasso. Tatlin received his artistic training in the traditional icon painter style. This style did not entertain Tatlin for long. In line with the Constructivist focus on functional sculpture using the unique properties of different materials, Tatlin began creating art that explored social concerns.

Perhaps Tatlin’s most famous work is his design for the Tatlin Tower, also known as the Monument to the Third International (1920). The large steel structure with revolving rooms and various other technologically advanced elements was truly the epitome of both Constructivist and Kinetic art. The tower was designed as a monument and a headquarters for the Communist International society. Although the building was never realized, the design stands as a testament to the values of Kinetic art and Revolutionary Constructivism.

Alexander Rodchenko (1891-1956)

A friend and colleague of Tatlin, Rodchenko is another famed Russian Constructivist and Kinetic artist. Rodchenko is most well known for developing what he called “non-objectivism.” Continuing the study of sculptures, Rodchenko began to work with objects that were not actually movable. Instead, his early work juxtaposes objects of varying materials, shapes, and textures, to spark new ideas in the viewer. Many of Rodchenko’s works include elements of discontinuity.

For example, a 1915 piece on canvas called Dance, an Objectless Composition captures a sense of movement through the abstract arrangement of various shapes, colors, and textures.

Later in his career, in the mid-1920s and 1930s, Rodchenko began to experiment with mobiles. In 1920, Rodchenko created a wooden hanging mobile called Hanging Construction. This naturally rotating mobile sculpture hangs by a single thread. The concentric circles in several different planes emphasize the sense of movement as the mobile turns, even though the sculpture only rotates vertically and horizontally.

Alexander Calder (1898-1976)

Calder is arguably one of the most well-known early twentieth century Kinetic artists, and he is particularly famed for his unique mobile creations and majestic public sculptures. The American artist first began to gain attention in the 1920s in Paris, and he became one of the most prominent figures of American Modernism. Calder is also a pioneering artist in the Kinetic Art Movement, known for infusing his works of art with motion.

Calder began his experiments with movement by creating wire figurines. Rather than drawing the figures on the page, he drew them in physical space. These animated drawings, with their moldable wire structure, carry a lot more motion than a paper drawing. Calder soon moved away from figurative sculpture and began creating abstract mobile forms. Using lengths of wire with a central frame and various metal forms that hung in abstraction.

Based on their shape, many historians do not consider these early Calder mobiles to be examples of Kinetic art, but by the 1960s, Calder was widely considered the master of mobiles. Calders Cat Mobile (1966) is a perfect example of his Kinetic mobiles. The head and tail of the cat appear to be in random motion, while the body remains stationary. The kinetic rhythm of the piece is emphasized by this contrast between motion and stagnation. Like many Kinetic artists, Calder relied on mathematical formulae to perfect the motion in his mobiles.

Kinetic art is a far-reaching and incredibly broad movement. From the early Impressionist depiction of shifting light and color, to the mechanically engineered sculptures of Tatlin and Gabo, there is no single Kinetic art definition. What underlies all of these utterances is the desire to capture the movement of time, space, and matter in the world around us.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is Kinetic Art?

Kinetic art involves the physical and conceptual impressions of movement through art. The Kinetic art movement was founded in the 1920s by Nuam Gabo and Antoine Pevsner.

What Are the Characteristics of Kinetic Sculptures?

Kinetic sculpture can be defined as installations created to give the impression of movement. Many kinetic sculptures have engines that drive moving parts, but others use the power of illusion to create movement.

What Galleries Have a Lot of Kinetic Art on Display?

There are many galleries around the world displaying kinetic sculptures. The Guggenheim Museum has many installations including Aventure Pictural by Yaacov Agam and Blondie by Alexander Calder. The Breakfast Kinetic Art Studio in New York also houses many modern kinetic sculptures.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Kinetic Art – An Overview of this Moving Art Term.” Art in Context. March 18, 2021. URL: https://artincontext.org/kinetic-art/

Meyer, I. (2021, 18 March). Kinetic Art – An Overview of this Moving Art Term. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/kinetic-art/

Meyer, Isabella. “Kinetic Art – An Overview of this Moving Art Term.” Art in Context, March 18, 2021. https://artincontext.org/kinetic-art/.