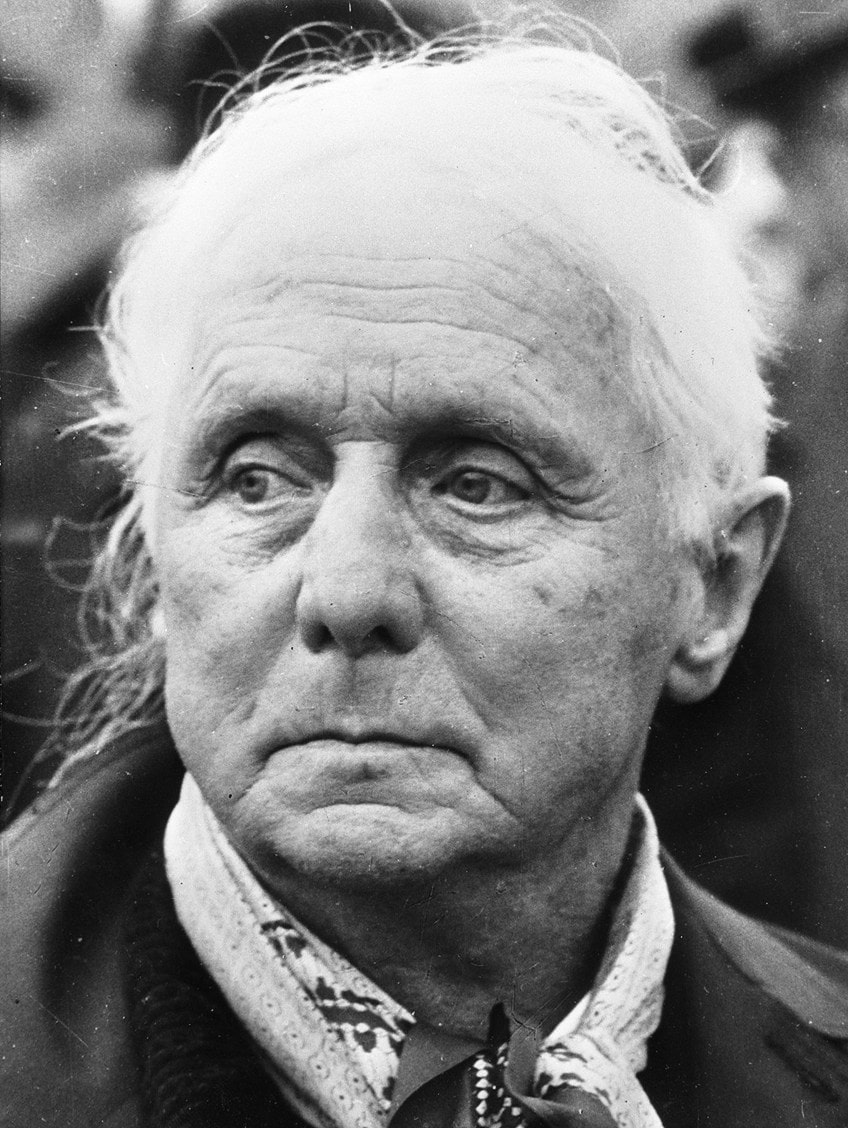

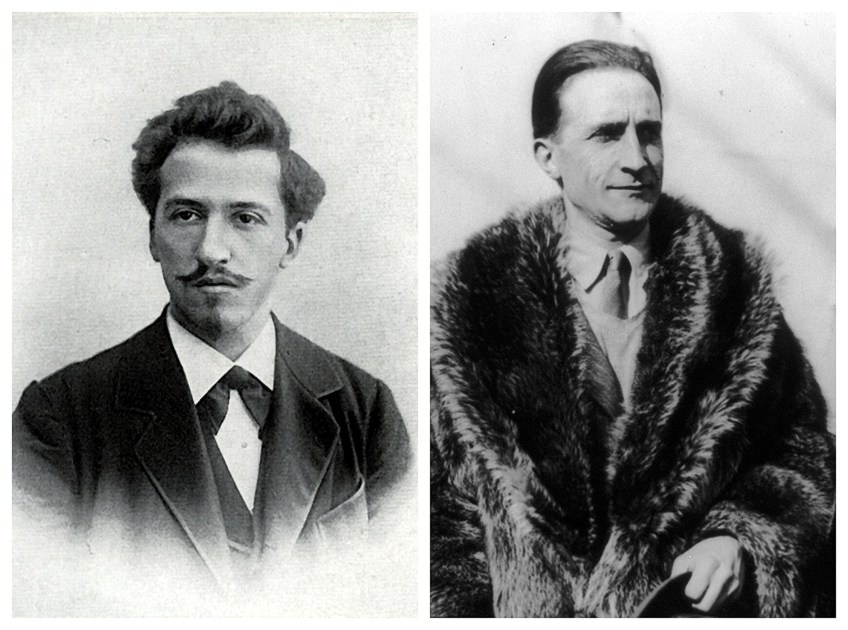

Max Ernst – An Artistic Biography and Portrait of Max Ernst

Max Ernst was a renegade, a provocative and inventive artist who explored his psyche for surreal images that challenged social norms. Ernst, a World War I veteran, was terribly disturbed by his experiences and strongly skeptical of Western civilization. These powerful emotions led straight into his perception of the modern world as illogical, which became the foundation of Max Ernst’s artwork. Max Ernst’s Surrealism and Dada artworks reflect his aesthetic vision, as well as his wit and vigor.

Max Ernst’s Biography and Art

Max Ernst’s paintings were pioneering examples of both Dadaism and Surrealism. His engagement with the psyche, social criticism, and wide-ranging experimentation in both topic and method continues to have an impact. Max Ernst’s artworks challenged art cultures and practices while demonstrating a profound understanding of the history of European art. Max Ernst’s Surrealism paintings were non-representational pieces with no clear themes that challenged the purity of art by criticizing religious iconography and inventing new ways to create artworks to convey the current condition.

| Nationality | German-American-French |

| Date of Birth | 2 April 1891 |

| Date of Death | 1 April 1976 |

| Place Born | Brühl, German Empire |

| Associated Movements | Surrealism, Dada |

Early Life

Max Ernst was born the third of nine children to a middle-class Catholic family in Brühl, near Cologne. Philipp, his father, was a teacher for deaf children and also an amateur artist, a fervent Christian, and a rigorous disciplinarian. He instilled in Ernst a desire to challenge authority, and his passion for painting and drawing in nature prompted him to pursue a career as a painter.

Ernst received no official art instruction other than this initiation to amateur art at home; therefore, he was accountable for his own artistic skills.

Ernst entered the University of Bonn in 1909 to study art history, philosophy, psychology, literature, and psychiatry. He toured sanitariums and became captivated with the artwork of mentally ill people; that same year, he also began painting, making drawings on the grounds of the Brühl castle, as well as paintings of his sister and himself. The artist then encountered August Macke and subsequently joined the Die Rheinischen Expressionisten group of painters in 1911, opting to pursue a career as an artist. In 1912, he went to the Sonderbund exposition in Cologne, where he was deeply impressed by pieces by Pablo Picasso and post-Impressionists such as Paul Gauguin and Vincent van Gogh.

Max Ernst’s artworks were shown at Galerie Feldman in Cologne that year, with that of the Das Junge Rheinland group, and then in other group shows in 1913. Ernst used a satirical technique in his works during this time period, juxtaposing repulsive elements with Expressionist and Cubism motifs. Max Ernst then met Hans Arp in the city of Cologne in 1914. The two became steadfast friends and had a 50-year-long connection. After finishing his training in the summer, Ernst’s life was disrupted by World War I. Ernst was conscripted and saw action on both the Eastern and Western Fronts.

The war had a terrible impact on Ernst; in his memoirs, he described his time in the army as follows: “On the first of August 1914 M[ax]. E[rnst]. died. He was resurrected on the eleventh of November 1918”

Ernst was allocated to chart maps for a brief spell on the Western Front, allowing him to resume painting. Max Ernst was among several famous painters who came back from their war duties extremely emotionally traumatized and mentally removed from European customs and conventional beliefs. Several German Expressionist artists, including Franz Marc and August Macke, were killed in battle during the war.

Artistic Training

Despite being mostly self-taught, Ernst was inspired by the paintings of August Macke and Vincent van Gogh. Giorgio de Chirico’s canvases ignited his curiosity in dream iconography and the surrealistic. Ernst used his childhood and military memories to create ridiculous and horrific scenarios. Ernst maintained a rebellious streak throughout his career, practically turning the world upside down in several of his paintings.

After returning to Germany following the armistice, Ernst, together with the artist-poet Jean Arp, helped found the Dada group in Cologne, while maintaining strong relations with the avant-garde movement in Paris. He married art history major Luise Straus, whom he had first met in 1914. In 1919, Ernst paid a visit to Paul Klee in Munich and studied Giorgio de Chirico’s works.

The same year, influenced by de Chirico, teaching-aide manuals, and other sources, the first of Max Ernst’s collages were created, a style that would come to dominate his creative endeavors. Ernst’s illogical image-making enabled him to make the worlds of dreams, the subliminal, and the unintentional all visible as he delved into his own mind for motivation and to address his own suffering.

Ernst was in Cologne curating journals and assisting in the creation of a Dada exhibition in a public restroom, where customers were greeted by a lovely young lady spewing horrible poetry.

Ernst’s sculpture was also on exhibit, as was an ax, which the spectators were encouraged to use to attack and destroy the piece of art. This audience participation event outraged bourgeois sensitivities. Ulrich Ernst, Ernst and Luise’s son, was born on the 24th of June 1920 and went on to become a painter. His marriage to Luise ended in divorce. He then subsequently met Paul Éluard, who became a lifetime friend, in 1921. Éluard purchased two of Ernst’s paintings – Celebes (1921) and Oedipus Rex (1922) – and chose six collages to accompany his poetry book Répétitions.

Mature Period

In 1922 Ernst moved to Paris and worked and lived there until around 1941 when the second world war made it extremely difficult for him to remain in Europe. With the release of André Breton’s First Surrealist Manifesto (1924), Surrealism proceeded to supplant Dadaism over the next few decades, and Ernst had become a fundamental component of the group.

Ernst and his artist colleagues began exploring the potential of autonomism and visions; indeed, his creative experiments were facilitated by hypnotherapy and hallucinogens. In 1925, Ernst began to experiment with frottage (pencil rubbings of substances such as natural wood grains, fabric, or foliage) in order to arouse the torrent of imagery from his unconscious, as well as decalcomania (the practice of transmitting pigment from one material to another by squeezing the two simultaneously).

His experiments and advances in technology resulted in finished images, unintended patterns, and unique textures, which he subsequently incorporated into his paintings and sketches.

This emphasis on material touch, as well as changing common items to create a picture that represented some type of collective awareness, would become crucial to Surrealism’s idea of automatism. He also invented the grattage method, which involves scraping paint over a canvas to show the impressions of objects put beneath it. This technique was utilized in his well-known work Forest and Dove (1927).

https://youtu.be/yudsr21M15M?t=81

The year following that, Ernst then worked with Joan Miró on various designs for Sergei Diaghilev. Ernst devised grattage, in which he trowelled color off his canvases, with the assistance of Miró. Ernst acquired a love of birds, which was evident in his art. In Max Ernst’s paintings; he had a bird as his alter ego, which he dubbed Loplop. He said that his alter-ego was an augmentation of himself, resulting from an early mix-up of birds and people.

He claimed that when he was a child, he awoke one night to discover that his favorite bird had perished; a few moments later, his father proclaimed the birth of his sister.

Loplop is frequently featured in Max Ernsts’ collages of the works of other creators, such as Loplop presents André Breton. Max Ernst’s painting The Virgin Chastises the Infant Jesus in Front of Three Witnesses (1926) sparked a lot of debate. Ernst married Marie-Berthe Aurenche in 1927, and his connection with her is said to have influenced the sensual subject matter of The Kiss and other pieces of that year. Luis Bunuel, a Surrealist, directed Ernst in the 1930 film L’age d’Or.

Ernst began sculpting in 1934 and studied under Alberto Giacometti. Peggy Guggenheim, an American heiress and art supporter, purchased a number of Max Ernst’s works in 1938 and presented them at her new gallery in London. Ernst and Peggy Guggenheim were wed sometime between 1942 and 1946.

Later Years

Hitler and the Nazis had assumed power over Germany by 1933. By the fall of 1937, Hitler had amassed around 16 000 avant-garde pieces from Germany’s state museums and had sent 650 paintings to Munich for his disastrous show (Degenerate Art). Ernst appears to have had at least two works on show in the exhibit, both of which have since completely disappeared or were most likely demolished.

When World War II broke out in September 1939, Ernst was incarcerated as an “unwanted alien” in Camp des Milles, near Aix-en-Provence, with compatriot Surrealist Hans Bellmer, who had previously fled to Paris. He had been residing with his partner and fellow Surrealist painter, Leonora Carrington, who had no choice but to sell their property to clear their debts and depart for Spain since she didn’t know whether he would return.

After being incarcerated on several occasions as a German subject, Ernst managed to escape France with the Gestapo hot on his tail.

As a migrant in New York, he encouraged an entirely new school of American artists alongside prominent avant-garde European artists like Piet Mondrian and Marcel Duchamp. Ernst’s disdain of conventional painting methods, styles, and images (as shown by his father’s work’s classical tradition) fascinated youthful American artists, who, like Ernst, aspired to establish a fresh and unconventional approach to art.

He had a notably great influence on the path of Jackson Pollock’s paintings, who became fascinated in Ernst’s collage features as well as his inclination to utilize his art as an abstraction of his interior condition. Ernst’s capturing of the subconscious and the incidental in his art creating, as well as his tremendous Surrealist experiments with autonomism and spontaneous writing, piqued the curiosity of the new artists.

In 1942, Ernst worked with “Oscillation,” or painting by spinning a paint-filled container pierced numerous times with holes across the canvas; Pollock was particularly taken with this.

Max Ernst then met the vibrant socialite Peggy Guggenheim, who was a gallery curator, and art lover who would also subsequently become his third wife. He gained intimate access to New York’s emerging art circuit due to Guggenheim’s popularity and connections. However, his marriage to Guggenheim was not long-lived, and in October 1946, he married Dorothea Tanning in Beverly Hills, California, in a double wedding alongside Man Ray and Juliet P. Browner.

From 1946 through 1953, the couple lived in Sedona, Arizona, where the high desert scenery inspired them and reminded them of Ernst’s previous work. Regardless of the fact that Sedona was isolated and home to just 400 herders, vineyard laborers, traders, and tiny Native American villages, their presence aided in the establishment of what would become an American artists’ community.

Ernst erected a tiny home on Brewer Road among the massive red rocks, and he and Tanning welcomed intellectuals and European painters such as Yves Tanguy and Henri Cartier-Bresson.

Sedona inspired the painters as well as Ernst, who wrote his book Beyond Painting and finished his sculptural masterwork Capricorn (1948) while living in Sedona. Ernst began to experience financial successes as a consequence of the book and its popularity. Ernst and Tanning eventually returned to France in 1953. Ernst received the major painting prize at the renowned Venice Biennale in 1954. Ernst worked as a painter until his death in 1976 in Paris.

Max Ernst’s Artwork and Style

Max Ernst disrupted artistic traditions while also being well-versed in European art history. He brought into dispute the purity of culture by producing non-representational compositions with no obvious narrative, making light of religious imagery, and creating new approaches to produce art to convey the existing status. Ernst was fascinated by the artwork of the mentally disturbed as a method of accessing basic feeling and unbridled creation.

Ernst was one of the first painters to use Sigmund Freud’s visionary ideas to probe into his own profound psyche in order to discover the source of his own originality.

Ernst was looking within while simultaneously interacting with the collective unconscious through shared dream imagery. Ernst aimed to attain a pre-verbal state of being by painting freely from his inner consciousness and striving to uncover the source of his own creativity. As a result, he was able to communicate his primal emotions and reveal his inner traumas, which were the subject of his collages and canvases.

This desire to create from the subconscious, sometimes referred to as automatic painting, was important to his Surrealist compositions and impacted the Abstract Expressionists who came after him.

Artworks

With Max Ernst’s collages such as Here Everything is Still Floating (1920), he developed a new reality in which unpredictability and incoherence portrayed the lunacy of WWI and called into question capitalist perceptions. These photographs were taken from scientific textbooks, ethnographic periodicals, and ordinary commerce brochures from the turn of the century. Despite the vain hunt for purpose, these playful works proved to be delightful and fulfilling in the end.

“Collage was considered as a form of crime, meaning one inflicted damage to nature,” the artist would later remark.

Max Ernst’s paintings such as Celebes (1921), with their bizarre juxtapositions of different items, display his devotion to Freudian dream theory. Despite this mismatch – a headless/nude lady, parts of equipment – the picture works as a full composition. Max Ernst’s artwork causes discomfort because spectators are unaware of his goals, as well as contempt because of its irrelevant representation of the human form (the headless body), which is cherished within art creating (since individuals are fashioned in God’s image).

Ernst’s work raises the question of whether reality is the “real” one: that of the nighttime and visions, or that of the waking consciousness.

Max Ernst’s Surrealism paintings often took playful jabs at the status quo of religious themes, such as with The Virgin Spanking the Christ Child (1926). The Virgin Mary, shown as an earthy, irritated mother, harshly paddles her little son – the rebellious infant Jesus – on his bottom, which bears red marks from her punitive hand. Paul Eluard, Andre Breton, and the artist himself are observing through the backdrop window and functioning as bystanders; all three appear unconcerned by the situation.

Ernst successfully subverts his own Catholic belief with its dedication to Christ’s mother Mary, while concurrently belittling much of Western art history with its expansion of affectionate scenes between both the Blessed Virgin Mary and the Christ baby, and undermining the doctrines, upper-class holiness of motherhood. Ernst’s picture is both irreverent and sharply amusing. As predicted, not everyone found the premise amusing, and the piece sparked much debate as an assault on Christianity and current morals.

Ernst also pioneered a new painting technique known as “Grattage”, as can be seen in his work Forest and Dove (1927). This painting exhibits Ernst’s’ grattage’ method, in which he scraped paint over the canvas to expose object impressions, which he invented with the Spanish surrealist Joan Miro. Grattage created a coarse texture that provided another layer to the painting, amplifying the thickness of a forest. It would be a folly to ignore Ernst’s German roots, with their Romantic legacy, and how this influenced his distinctive psychology. In his apocalyptic works, the German idea of Ahnung, or the dread of imminent doom, undulates.

He was well-versed in Wagnerian stories of strange and bewitching German woodlands; the Surrealists eventually embraced forests and dark corners as metaphors for the creative mind.

While most of his work was non-representational, there are a few rare examples where he was directly reacting to current political events such as The Fireside Angel (1937). This strange creature looks to be jumping, arms and legs outstretched, with a gaudy, yet joyful, grin on its face. The figurines and their limbs are discolored and deformed. Furthermore, its limb appears to be giving birth to another entity, as if a malignant mass is spreading.

The painter was motivated to produce the image after Franco’s fascists defeated the Republican camp in the Spanish Civil War. Ernst attempted to produce a picture that reflected the impending turmoil that he believed was sweeping over Europe and coming from his own Germany. Returning to the innocuous and deceptive title, Ernst’s play aimed to entice audiences with pleasant phrases, only to jolt them into doubting their own convictions by naming creatures as if angels. Another politically driven statement piece was Europe after the Rain II (1942).

Europe after the Rain II provides witness to the impossible reign of conflict that decimated Europe at the period, as viewed in the perspective of 20h-century European history. Ernst’s creative representation of the Spanish Civil War and the onset of World War II is unique in this work. The grattage method, used to produce the ruins shapes, aptly recalls Europe’s catastrophic disaster.

The time range assigned to the work shows that Ernst began this painting in France and finished it in the United States while the war raged on and Europe’s fate remained undetermined.

Ernst has created an evocation of a massive catastrophe on this otherworldly painting. An armored, bird-headed creature – maybe a soldier – confronts a female figure with his spear or damaged battle standard in the midst of the destroyed terrain. It’s been hypothesized that the figures are enormous garden statues or semi-mythical heroes of a future conflict. As stated previously, Ernst’s usage of the bird-human image might be self-referential.

Max Ernst’s Artistic Legacy

While still living, Max Ernst accomplished the unusual feat of building a glowing image and critical reputation in three countries (France, Germany, and the United States). Although Ernst is more known to art historians and scholars than to the general public, his influence on the development of mid-century American art is indisputable.

Ernst worked with the Abstract Expressionists both personally and through his son, Jimmy Ernst, who went on to become a well-known Abstract Expressionist artist after the war as a result of his association with Peggy Guggenheim.

Ernst grew interested in Southwest Native American Navajo art as a creative influence while living in Sedona. The later Abstract Expressionists, particularly Pollock, became captivated with the art of sand painting, which is strongly linked to healing practices and spiritual incantations. Ernst remains a pivotal figure for artists who are strongly concerned with the method, psychology, and the urge to shock and challenge social norms.

In his hometown of Brühl, Germany, the Max Ernst Museum was launched in 2005. It is housed in a late-classicist 1844 structure that has been combined with a contemporary glass pavilion. Ernst used to frequent the ancient ballroom as a popular social location when he was younger.

The collection includes canvases, sketches, frottages, assemblages, practically all of his lithographic pieces, over 70 bronze sculptural works, and over 700 papers and pictures by Henri Cartier-Bresson, Man Ray, Lee Miller, and others.

The artist gave pieces to the City of Brühl in 1969, which formed the foundation of the collection. As many as 36 paintings, presented by the painter to his fourth wife Dorothea Tanning, are on loan from the Kreissparkasse Köln on an indefinite basis. Among his notable works are the sculptures The Teaching Staff for a School of Murderers (1945) and King Playing with the Queen (1944). Other artists’ works are also shown in the museum.

Exhibitions and Honors

From 1970 to 1972, a retrospective of 104 of Max Ernst’s paintings from the Menil Collection spanning the years 1920 to 1968 toured Europe. The exhibition premiered in Paris in April 1971, on Max Ernst’s 80th birthday, and was supplemented by 44 works from various collations. Here are a few more notable exhibitions and honors of the artist:

- 1954 – Grand Prize for Painting – Venice Biennale

- 1959 – Grand Prix national des arts – Musée National d’Art Moderne Paris

- 1961 – Museum of Modern Art, New York

- 1962 – Tate Gallery London

- 1969 – Moderna Museet, Stockholm

Notable Artworks

Max Ernst’s paintings were forerunners of both Dadaism and Surrealism art. His interest in psychology, societal critique, and broad experimentation in both theme and approach continues to have an influence. Max Ernst’s artworks questioned art cultures and practices while exhibiting a deep awareness of European art history. Here is a list of some of his most important works:

- Crucifixion (1913)

- Town with Animals or Landscape (1916)

- Aquis Submersus (1919)

- Fiat modes (1919)

- He’s Not Very Well, the Hairy-hoofed Horse (1920)

- Murdering Airplane (1920)

- All Friends Together (1922)

- The Wavering Woman (1923)

- Ubu Imperator (1923)

- Paris Dream (1925)

- Loplop Introduces a Young Girl (1930)

- The Giant Snake (1935)

Recommended Reading

Max Ernst was a fascinating artist. Hopefully, you have enjoyed reading about him today. Perhaps you would like to learn more and would be interested in purchasing a Max Ernst biography. We have compiled a list of awesome books in case you would like to explore the artist’s life and art even more!

A Little Girl Dreams of Taking the Veil (2017) by Dorothea Tanning

While exploring an illustrated book of items, timepieces, tools, and clothes—artist Max Ernst was fascinated by the unexpected juxtapositions of the things. Ernst pioneered the collage novel and converted ordinary advertising imagery into revelatory dramas rooted in his visions and inner desires by modifying Victorian-era prints into dazzling tableaux and adding brief subtitles. Its hallucinatory images revolve around the dreams of a young girl who breaks her virginity on the day of her holy communion and vows to become a nun. Ernst, a Dadaist and Surrealist artist, explores the non-rational but very real junction of religious ecstasy and sensual desire with comedy and sarcasm. This truly strange novel retains its element of surprise as well as its imaginative force a century after its initial publication.

- A "collage novel" originally published in 1930

- Dada and Surrealist artist Max Ernst blends humor and irony

- A profoundly peculiar book with great shock value and imagination

Une Semaine De Bonte: A Surrealistic Novel in Collage (1976) by Max Ernst

This is one of Max Ernst’s (b. 1891) iconic collage masterpieces. Ernst was a prominent role in the surrealist movement and was one of the most creative painters of the twentieth century. Ernst created this series of 182 weird and darkly hilarious collage pieces of classic visions and sensual fantasies that appear to magically entice the unconscious into view using the vintage collection and pulp fiction illustrations: Serpents arrive in the drawing-room and bedroom, a nobleman has the face of a lion, and the salon floor changes to water, on which some individuals appear to be able to walk while others perish.

Max Ernst was a renegade, a provocative and inventive artist who explored his psyche for surreal images that challenged social norms. Ernst, a World War I veteran, was terribly disturbed by his experiences and strongly skeptical of Western civilization. These powerful emotions led straight into his perception of the modern world as illogical, which became the foundation of Max Ernst’s artwork. Max Ernst’s Surrealism and Dada Artworks reflected his aesthetic vision, as well as his wit and vigor.

Frequently Asked Questions

Who Was Max Ernst and Why Was He Famous?

Max Ernst was a German painter and sculptor who was a strong champion of insanity in art and the founder of the Surrealist Automatism movement. He managed to obtain naturalization in both the United States (1948) and France (1958). Ernst’s early pursuits were psychology and philosophy, but he dropped out of the University of Bonn to pursue painting.

What Style Were Max Ernst’s Artworks?

Ernst was looking within while simultaneously interacting with the collective unconscious through shared dream imagery. Ernst aimed to attain a pre-verbal state of being by painting freely from his inner consciousness and striving to uncover the source of his own creativity. As a consequence, he was able to articulate his basic feelings and disclose his innermost experiences via his collages and canvases. This urge to paint from the subconscious, often known as automatic painting, was central to his Surrealist works and influenced the Abstract Expressionists who followed him.

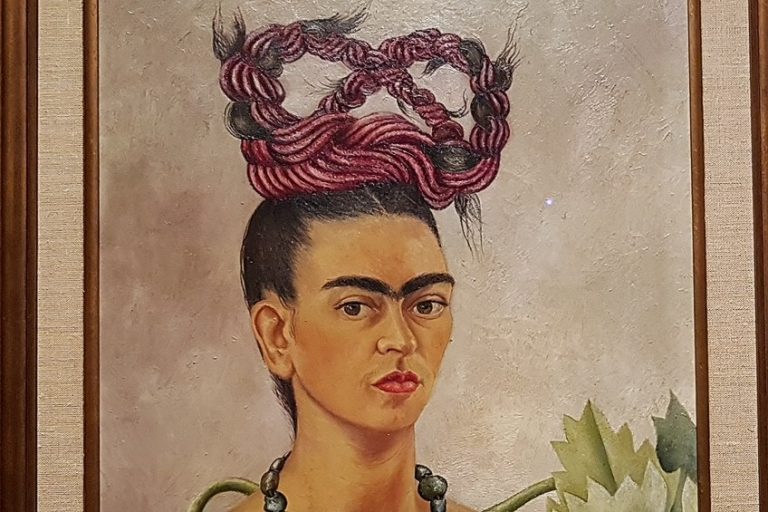

Who Created the Portrait of Max Ernst?

Max Ernst did not create this painting. The Portrait of Max Ernst was painted by Leonora Carrington. It does, however, display Surrealist imagery.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Max Ernst – An Artistic Biography and Portrait of Max Ernst.” Art in Context. February 21, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/max-ernst/

Meyer, I. (2022, 21 February). Max Ernst – An Artistic Biography and Portrait of Max Ernst. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/max-ernst/

Meyer, Isabella. “Max Ernst – An Artistic Biography and Portrait of Max Ernst.” Art in Context, February 21, 2022. https://artincontext.org/max-ernst/.