Mannerism Art – A Look at the Ins and Outs of the Mannerism Period

Mannerism Art started in Italy near the end of the High Renaissance during the early 1500s. It was also referred to as the Late Renaissance. The Mannerism style was almost a “rebirth” of all that was explored and discovered in art (to the point of perfection) during the Renaissance period. Art became less naturalistic and more artificial in its portrayal.

Rejecting the Classical for Style: What Is Mannerism?

Mannerism Art was not only a style, but it was stylish in its manner. Below, we explore this relatively short art period nestled between the Renaissance and Baroque art periods. First, we will look at the definition of the term, including what it meant in relation to the timeframe it occurred, which is dated to around 1520.

Mannerism Art Definition

For us to understand the Mannerism Art definition related to the whole movement, let us start with the word “mannerism”. The word’s origins come from the Italian word maniera, which means “style” or “manner”. If we go further, the term maniera originates from the Latin root manus, meaning “hand”. From Old and Middle French roots the word indicates “method” or “way”.

This is exactly what Mannerism was – a particular and somewhat peculiar “way” of doing things, in this case, art.

Although the term directly translates to “style” or “manner” from Italian, it found its way into the hands of many other meanings, some with negative interpretations on the artificiality of the style compared to the Renaissance artists that came before it. Others defined it simply as the style of art during the 1500s (16th Century).

Historical Influences of Mannerism Art

There were a lot of historical influences that impacted the Mannerism movement and style. It was a time in European history of great changes and evolution, not only politically, but also religiously and economically. The role of the Church and its influence on the masses was a considerable influencing factor. Additionally, the rise of Protestantism catalyzed many new perspectives and wars related to religion, which undoubtedly affected everyone, including the way art was made and portrayed.

Mannerism Art depicts the human figure in new, quite literally (and figuratively) twisted shapes. This hints at one of the key influences on Mannerists, which is the Hellenistic period sculpture and statue, Laocoön and His Sons (c. 200 BCE). It portrays the mythological story during the Trojan War of the priest Laocoön being attacked by serpents from the sea. His sons were Antiphantes and Thymbraeus.

The dynamism depicted by the figures in this statue was a shift from the more austere and serene appearance of Roman sculptures and statues. Many scholarly sources discuss the element of figura serpentinata, which means “serpentine figure”, that is portrayed in this sculpture, and how it acts as an influencing factor on Mannerist Art in how they similarly emulated the serpentine shape in their painted and sculpted figures. The writhing of the figures also suggests heightened emotion and intensity.

The Different Phases of Mannerism

Mannerism Art is viewed in two phases, namely, Early Mannerism and High Mannerism. The Early Mannerism phase started closely to the High Renaissance, and artists during this period created art opposing that of the Renaissance masters. This phase is often described as “anti-classical”.

The High Mannerism period was different to the earlier period in that it sought to imitate the art from the Renaissance period. It is referred to as having a “courtly” style because of its domination within courts, and was generally surrounded by groups of people more associated with intellectual faculties and interests.

The High Mannerism period was also referred to as Maniera Greca, which is a term describing painting during the Medieval era in Italy, influenced by Byzantine Art. The term itself translates to “Greek style”, and it described this style of art, which also influenced the Mannerists.

This period was marked for its artificiality, in other words, the art was deliberately trying to gain attention from viewers. It was also criticized for its sense of artifice and “unnatural” manner of work. There was a keen eye for detail and figures were given more attention in the way they were positioned, appearing more elegant and poised.

Michelangelo was a primary influence for artists of this phase of the Mannerism style.

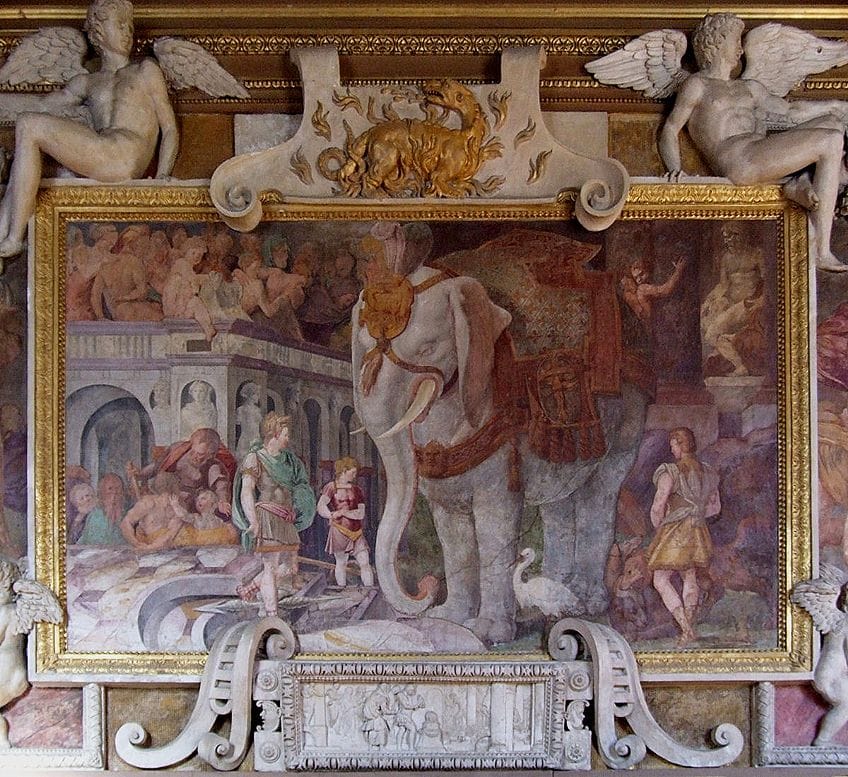

Mannerism in Northern Europe

Although the Mannerism period started in Italy – Rome and Florence specifically – it took place in various other countries in Northern Europe, namely France, Britain, Prague, and the Netherlands. The School of Fontainebleau was led by Rosso Fiorentino (1494/1495-1540), an Italian Mannerist, who was invited by Francis I to decorate the Palace of Fontainebleau. The art was highly decorative, ranging from paintings, architecture, and furniture. Rosso was also known for utilizing stucco relief, which is a decorative motif.

Various court arts became popular during this time. For example, in Prague Flemish Mannerist Bartholomeus Spranger (1546-1611) was the primary artist for Rudolf II. Spranger’s paintings explored mythological scenes with emphasis on the nude figure. His paintings were dynamic and decoratively rendered.

Other countries like the Netherlands saw famous printmaker Hendrick Goltzius (1558-1617) pioneer the Mannerist style. He was influenced by Spranger and often created prints from Spranger’s paintings. However, he also pioneered various techniques in etching, like the “dot and lozenge” and the “swelling line”. His figures were often overly muscular and extravagant in anatomical appearance.

Mannerism Art Characteristics

Mannerism Art can be primarily characterized by its seemingly opposite style and approach compared to the Renaissance artists, who were more refined and precise in their portrayal of real life in the arts, whether it was painting, sculpture, or architecture. Below, we look at various defining characteristics that help us understand Mannerism’s raison d’être.

Form: Towards Expression

The Mannerism style can also be described as more expressive and “exaggerated” in its nature, all the while not quite simulating nature itself. Mannerism painting was a new exploration and depiction of life and nature, which meant that within the context of the main trends of art during the 16th century, it was something wholly different than expected.

The Mannerists’ style was clearly observed in their subject matter. We will notice how the limbs on human figures are depicted more elongated and not in anatomical proportion. It also depicts figures in their characteristic serpentine shapes. This suggests more personal expression in rendering subject matter instead of remaining with true-to-nature renderings. An example of this can be viewed in the paintings of one of the most prominent Mannerists, Francesco Mazzola, more commonly known as Parmigianino (1503-1540).

Parmigianino, or “little one of Parma”, was well-known for portraying figures with elongated limbs, evident in his famous painting Madonna of the Long Neck (1530-1533). As is clear from the title of this work, Madonna is portrayed with a disproportionately long neck. Additionally, his self-portrait, Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror (1524) depicts the artist himself exploring the effects of the mirror on his image, particularly the elongated fingers in the foreground.

Many Mannerists also explored their expression of subject matter by combining or hybridizing the human figure with elements of nature. We see this in the works of Italian painter Giuseppe Arcimboldo (c.1526/1527-1593). His human figures were painted as portraits, except that he composed them of organic elements from the likes of vegetables, fruits, and meats, as well as other objects like books and bowls (fashioned as hats).

Color: A Sense of Falsity

Mannerists also explored an exaggerated palette of colors. Many artists used non-local colors with strong contrasts. Notable colors used were blues, yellows, pinks, and greens. Artists also depicted skin tones in exaggerated spectrums, where some figures would appear starkly pale while others would appear overly cream, as if a spotlight were directly emanating from them.

This was another aspect related to the Mannerism style – the play on contrasts of light and dark. While some artists utilized the techniques from the Renaissance, like chiaroscuro, Mannerists applied these in stark contrast compared to the Renaissance artists like Leonardo da Vinci. The attention to light and dark created more dramatic emphasis for scenes.

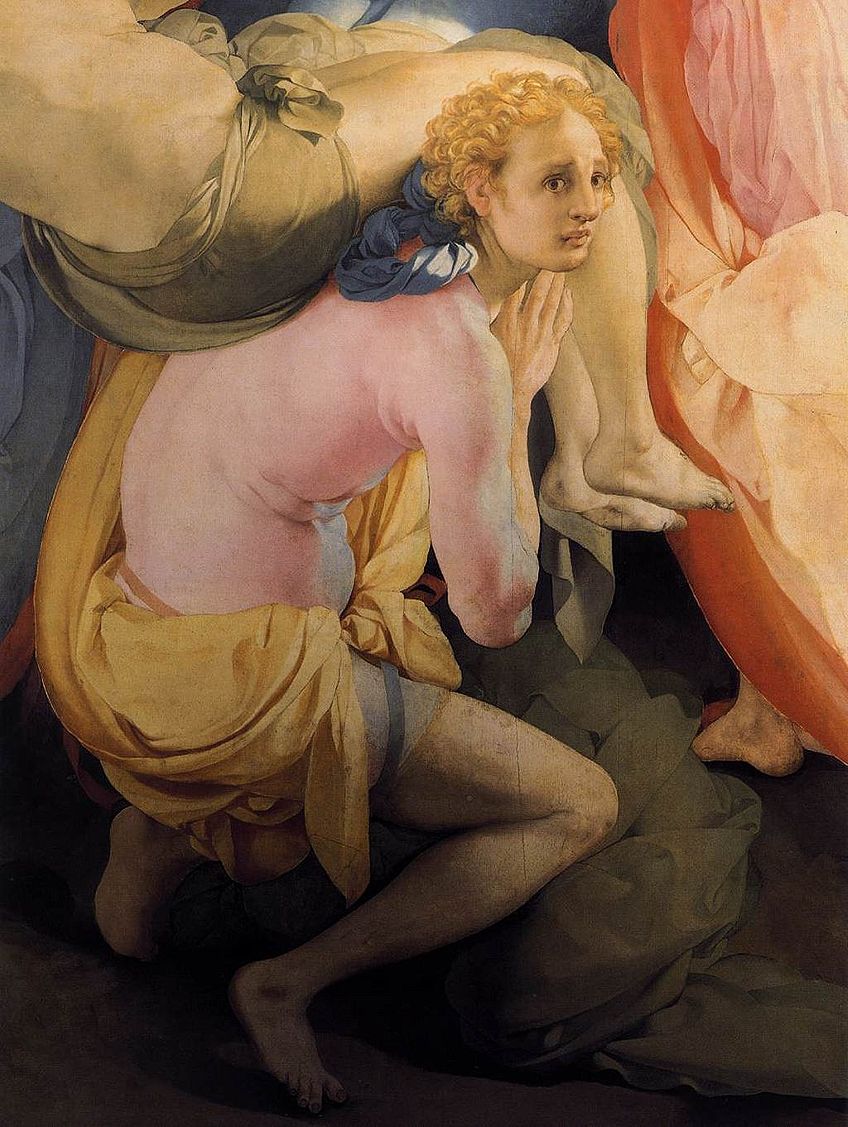

An example of the oftentimes described “rich” utilization of color is evident in the artworks of Mannerists like Jacopo da Pontormo (1494-1557), one of the pioneers of the art movement. His painting, The Deposition from the Cross (1528), depicts almost illustrious renderings of colors; we notice pinks, blues, and greens on the subject matter.

Famous Mannerist Artists

While there were many notable Mannerism artists, below we will look at some of the familiar names of the time within the painting, architecture, and sculpture modalities of the Mannerism style.

Mannerism Painting

Mannerist painting became a cornerstone of art, moving in a new direction after the High Renaissance. We will notice from the Mannerist painters discussed below how expression and stylistic principles became more important than the need to make a painting’s subject matter look exactly like its natural counterpart. It was a revolutionary thread woven into the beginnings of the ideals of “art for art’s sake”.

Jacopo da Pontormo (1494 – 1557)

Jacopo da Pontormo was one of the early Mannerists, pioneering the Mannerist painting style with his more expressive utilization of color, form, and composition. Although Pontormo utilized Renaissance techniques like chiaroscuro, his style nonetheless developed more away from the natural portrayals we see from the Renaissance artists.

Pontormo had early exposure to Renaissance Art, having traveled to Rome to view the Sistine Chapel done by Michelangelo. We can see how the artist still applied principles from the High Renaissance, evident from his earlier work like the Visitation of the Virgin and St. Elizabeth (1514–1516). For example, classical elements like an architectural space surrounding the figures as well as more naturalistic effects from the colors.

However, in the above-mentioned work, we can also see small hints of a more expressive style emerging. For example, the shapes of the figures appear more serpentine-like as well as more elongated. The subject of this work depicts the pregnant St. Elizabeth visiting the similarly pregnant Virgin Mary, where she is also bowing in front of Mary.

In Pontormo’s later years he created another painting based on this scene, however, we can see the artist’s full immersion into the Mannerism style. The Visitation (1528–1529) depicts the same two pregnant women, St. Elizabeth and the Virgin Mary. Compared to Pontormo’s earlier version, the scene is almost a close-up with only four figures instead of several occupying the space.

We notice the figures dominating the foreground with hardly any indication of what is happening in the background. The background depicts a glimpse of some architectural setting, but we cannot seem to discern more. The perspective is also as enigmatic as the scenic context the figures are placed in. Furthermore, we see characteristics of Pontormo’s Mannerist style also depicted in his portrayal of the rich, vivid, colors of the women’s clothing and the shapes of their bodies.

Pontormo’s The Deposition from the Cross (1528) is one of his most popular artworks and a classic example of the Mannerism style. The scene depicts various figures filling the foreground with anguished expressions. We will also notice a lack of any other contextual objects to inform the scene. All we notice is a cloud to the top left of the composition (said to symbolize the Holy Spirit) – we see slight hints of the sky and the ground too.

Pontormo’s figures are also clad in rich colors of blues, pinks, and greens with the characteristic serpentine shape we see so often depicted in the Mannerism style. Additionally, the figures are disproportionate in their anatomy, for example, the figure kneeling on the ground has a longer torso and neck than what is natural.

Furthermore, the other figures appear seemingly unperturbed by the weight of Christ’s body, as well as not weighed down by gravity themselves – their bodies seem weightless in space. It is believed that Pontormo drew inspiration from Michelangelo’s Pietà because of the way Christ’s body is positioned and contorted.

El Greco (1541 – 1614)

The artwork by El Greco is worth noting as he is often considered a forerunner of the Expressionist movement, also influencing numerous other contemporary artists like Pablo Picasso. In fact, Picasso painted a portrait of him titled Portrait of a Painter, After El Greco (1950).

Born in Crete as Doménikos Theotoképoulos, El Greco was initially an icon painter with exposure to Byzantine and Renaissance art styles. He moved to Rome and then Spain during his later years, where he started developing his own style of art in line with the Mannerist painting at the time.

We will notice that his paintings are typical in the Mannerism style with non-local colors, elongated figures, and figurative interpretation of subject matter and composition.

While he still depicted religious scenes typical of the Renaissance period that dominated culture, it was more than just that to El Greco – he was deeply religious himself and believed his art meant more. In fact, his art was testimony to the divine and he sought to depict it fervently within his compositions.

Some of his popular works include his early painting, The Holy Trinity (1577-1579) Here we see the depiction of the dead Christ held by God and surrounded by angels, with a white dove above God’s head. Behind the holy figures is golden light, which is juxtaposed by the gray clouds underneath the figures – this symbolizes the aspects of life and death.

Although this work is in line with Renaissance ideals, we will notice how El Greco incorporates his own style and expression using thick and dark outlines with heavy shadows around it, elongated figures, and an otherworldly effect due to his more expressive and figurative approach to the subject matter.

Another popular artwork is The Vision of St. John (1608-1614), which depicts the scene relating to the Fifth Seal from the Book of Revelations in the Bible, particularly martyrs receiving their white robes. We see various nude figures in active poses claiming their robes, except that the robes appear in different colors, some being rich yellow and green along with white. The primary figure in the foreground is Saint John with open arms.

El Greco painted his figures in stark contrasts of colors with his characteristic shading and dark outlines. His figures are also expressive, displaying intense emotions and gestures. The overall color of the painting is dark in tone with an elaborate sky overhead as gray with slits of light coming through. Furthermore, El Greco’s figures are elongated with minimal detail given to their proportion or anatomical correctness. This is a clear indication of the move to more expressive, less naturalistic, portrayals of the human figure.

Mannerism Architecture

Mannerism architecture was known as a “play” on the harmony of structure related to the Renaissance period. Where the Renaissance period sought to emulate the Greek and Roman ideals of classicism in architecture, which were “symmetry”, “order”, and “proportion”, the Mannerists sought to create more “rhythm” in their structures – this also allowed for more freedom of expression.

Michelangelo (1475-1564) was known as one of the leading figures for Mannerism architecture. He is well-known for his architectural work for the Laurentian Library in Florence (commissioned by Pope Clement VII). We notice motifs near the columns intended for decorative purposes, as well as the varying shapes of the steps of the staircase and more dynamic movements of structural elements like columns and corners, which recede and protrude.

Giulio Romano (c.1499–1546) was another prominent architect within the Mannerism style, although he was mainly a painter and sculptor. An example of his designs in architecture is seen on the Palazzo del Te (1524-1534), which was intended as a “pleasure palace” for Federico II Gonzaga, who ruled the city of Mantua, Italy.

This building included elaborate decorative motifs, grottoes, windows, and doors appearing real within a square enclosure with a courtyard. Frescoes covered the whole building with various scenes of mythology and animals like horses.

The variety of forms and shapes making up the architectural whole of this building is a famous example of how the Mannerism style grew in architecture, and how, eventually, this style developed into the Baroque style.

Mannerism Sculpture

Mannerism sculpture was like the style of painting; we will notice the elongation of figures and non-naturalistic tendencies where proportions are not symmetrical. Forms were also in the characteristic serpentine shapes. Mannerism sculpture conveyed the dynamic movement of the subjects, as well as qualities like strength and impassioned gestures.

Rape of the Sabine Woman (1583) by Jean de Boulogne, or Giambologna (1529-1608), is an example of the serpentine shape we see in the Mannerism style. Furthermore, Giambologna was a popular Mannerism sculptor. He was originally from Flanders, but moved to Rome to study and work on commissions from the Medici family.

His other marble work (although he adeptly sculpted in bronze) was Samson Slaying a Philistine (c. 1562) depicting Samson actively in the process of killing the Philistine and Hercules Beating Nessus (1599), which shows Hercules in the process of killing his enemy. What is similar in both sculptures is the dynamism of the figures in action with one another. They are similarly enmeshed with one another, which further highlights the serpentine shapes.

We also see the Mannerism style in Benvenuto Cellini’s (1500-1571) bronze sculpture, Perseus with the Head of Medusa (1545-1554). It was sculpted in a way where viewers can observe it from various angles, much like other sculptures within the Mannerism style. It is also reminiscent of the Renaissance sculptures of Donatello’s David.

This sculpture was commissioned by Duke Cosimo I de’ Medici and indicates the intricate political meaning inherent in sculptures made during the time, specifically sculptures in the Piazza della Signoria in Florence, which is the political center of the city.

Beyond Mannerism: The Evolution of the Perfect

Mannerism started to reach its peak near the later stages of the 1500s and the start of the 1600s. This was a period when Baroque Art started to gain momentum, which was an art movement with more emphasis on decorative effects and dramatism – almost a natural evolution of Mannerism Art.

Although it may have become obscured over time and forgotten, at some point in time Mannerism Art was explored again by artists from different periods. For example, French Romantic painter Eugène Delacroix was influenced by El Greco, including many great contemporary artists, specifically Expressionist artists like Max Beckmann and Cubist artists like Pablo Picasso.

While Mannerism was a short art period in European history, it nonetheless lay new foundations in a manner the Renaissance did not. Artists slowly started to evolve the perfect form of the Renaissance period into something more figurative, attached to a deeper meaning other than mathematical accuracy and proportion.

Take a look at our Mannerism webstory here!

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is Mannerism?

Mannerism was a stylistic movement during the 1600s. It occurred as a continuation and reaction to the High Renaissance and ended with the onset of the Baroque period. Mannerism was a shift in perspective for many, especially within the art world (painters, sculptors, and architects). Many moved away from the Classical ideals of perfection and proportion that defined the Renaissance period into a more figurative and non-naturalistic approach to art.

What Is the Mannerism Art Definition?

The term “Mannerism” directly translates to “style” or “manner”, from the Italian word maniera. However, the origin of the word is traced as far back as Latin and Old French, namely, “hand” (from the Latin word manus) and “method” or “way” (from Old and Middle French manere or meniere. The term has been debated many times, often as insulting to the somewhat chaotic type of art style after the Renaissance. However, now it is used to define and name the art period.

What Are the Main Characteristics of Mannerism?

The main characteristics of Mannerism in art are non-naturalism, artists did not portray their subject matter as true-to-nature. We see more disproportionate figures with elongated limbs and exaggerated features, a richer utilization of colors, and a dynamic display of movement through the application of the serpentine shape, also referred to as figura serpentinata, which means “serpentine figure”.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Mannerism Art – A Look at the Ins and Outs of the Mannerism Period.” Art in Context. May 5, 2021. URL: https://artincontext.org/mannerism-art/

Meyer, I. (2021, 5 May). Mannerism Art – A Look at the Ins and Outs of the Mannerism Period. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/mannerism-art/

Meyer, Isabella. “Mannerism Art – A Look at the Ins and Outs of the Mannerism Period.” Art in Context, May 5, 2021. https://artincontext.org/mannerism-art/.