Donatello “David” – Looking at Donatello’s Two “David” Sculptures

When people talk about Donatello, David is the sculpture that first comes to mind. They could be referring to one of two statues. Donatello’s David statues include one made of marble and the more famous statue of David made of bronze. Both of Donatello’s David sculptures are located in Florence’s Museo Nazionale del Bargello.

Donatello’s David Statues

Cosimo de’Medici, Florence’s most influential figure, erected his family’s mansion on a key street in the city between 1445 and the mid-1450s. Cosimo, a wise patron, saw that the look of this powerful building, constructed by Michelozzo, would be reflected on his family.

Although legally ordinary citizens of a republic, the Medici dynasty ruled the city’s politics, which they skillfully concealed.

The building conveyed an impression of power and elegance while evoking intentional connotations with the city’s republican administration via the rusticated masonry of the lower floor, which mimicked that of the Palazzi dei Priori, popularly called the Palazzo Vecchio.

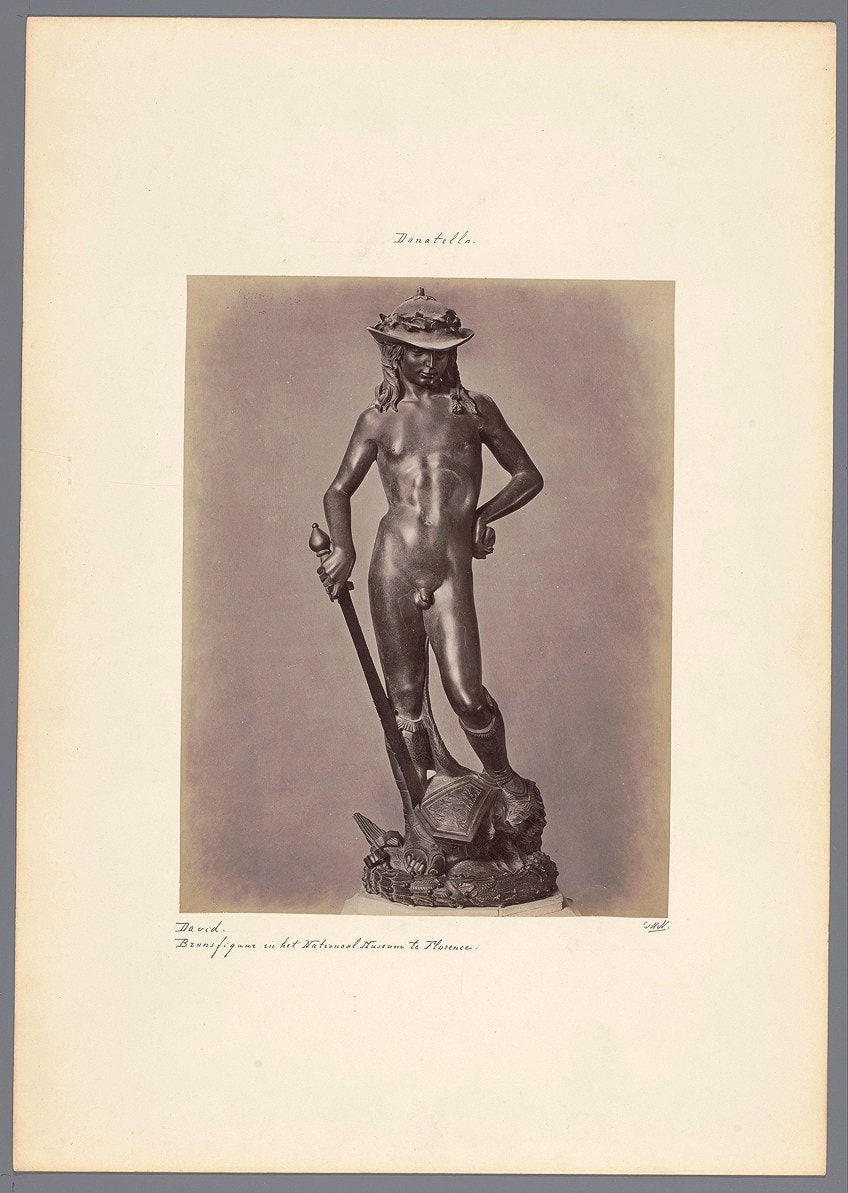

A private residence was never personal in the contemporary sense for a public man like Cosimo: The Palazzo Medici was a center of commerce and busy social exchanges, with an open courtyard clearly visible from the road leading to the main door. Donatello’s David sculpture in bronze, one of the most groundbreaking masterpieces of the early Renaissance period, perched high on an elevated base and was visible to visitors while the palace’s main door was open.

This, however, was not the first of Donatello’s “David” statues. But who exactly was the statue of David based on?

Who Is the Person in the Statue of David?

The subject of this famous monument is David, the king-to-be and protagonist of the Bible in Hebrew, who as a young person slew the Philistine giant Goliath and set his tribe free. In Donatello’s work, David’s innocence is evident: his nude body is that of a youngster, vividly contrasted with Goliath’s heavy facial hair and age, whose decapitated head falls at his feet. David’s vulnerability is highlighted by the stone he grips in his left hand, a memento that, while brandishing a sword, he brought down his massive opponent with a single slingshot.

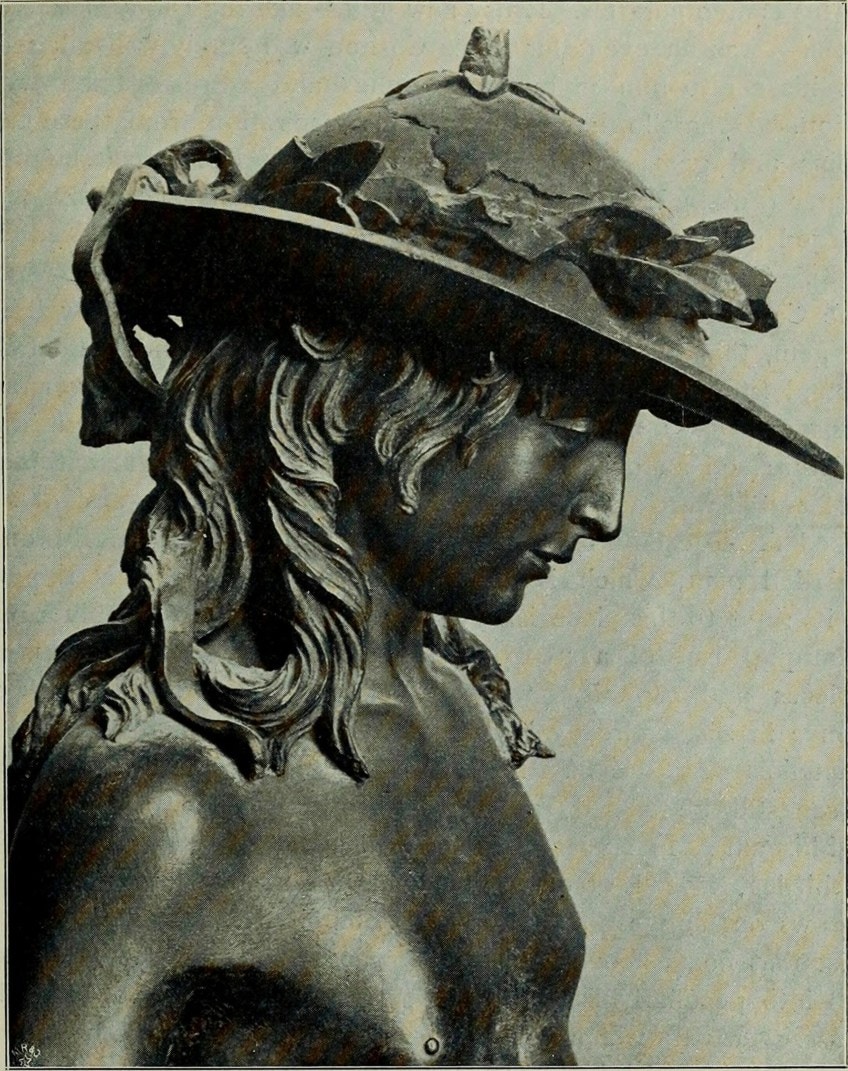

The lesson is clear: David won via God’s favor rather than physical power. While the scriptural tale recalls David refusing to battle Goliath with the armor his father had given him, it never recounts his being stripped nude. All prior depictions of David are on display, such as an earlier marble sculpture created by Donatello himself. It was rare to depict David completely nude, except for a shepherd’s hat adorned with triumphant wreaths and beautiful footwear.

David’s nakedness fulfills numerous purposes.

Why Is David Naked?

Exposing his young and weak physique emphasizes the remarkable nature of his victory. David is practically stripped naked in front of God and the audience, triumphant solely by God’s will. The sculpture, which stands in contrapposto and displays correct anatomy, also illustrates the rising concern with humanism, a philosophical movement that drew inspiration from the Greco-Roman past. David’s nakedness is evocative of old Greek and Roman sculptures, such as Spinario in his youth.

This ancient bronze sculpture in Rome’s Lateran Palace had already influenced Donatello’s contemporaries, Lorenzo Ghiberti and Filippo Brunelleschi, who both riffed on the figure in their various bronze panels depicting the Sacrifice of Isaac formed for the contest of the Florentine baptistery doors.

Being depicted without clothing had good implications in ancient art: ancient Greek and Roman deities and heroes communicated their purity through their idealized naked bodies. Donatello adopts this tradition by depicting David naked. Renaissance Christians would have viewed David’s nudity as an advance on the previous norm, heroizing a Judeo-Christian figure rather than a heathen one. This leads us to yet another significant element of the work: its original installation atop an elevated column.

This echoes a medieval tradition of depicting pagan rituals on a column with the theme of a naked figure—what renaissance viewers would have considered an “idol.”

This is depicted in the Flagellation of Christ (after 1444), the mural by Piero della Francesca in which the scriptural martyr is tormented while bound to a column fitted with a naked “ancient” figure at the top. Putting the biblical character into context in this pose, David may have symbolized the Christian faith’s victory over pagan Antiquity, rendering the monument both stylish and Christian.

The Donatello David statue’s sex is uncertain when viewed from behind. In this patriarchal culture, his androgyny may have served as another reminder of his inability to fight. Power was passed down from father to son in Renaissance Italy, and both secular and religious authorities focused on men’s and masculinity’s dominance. Donatello’s David’s sexual ambiguity, even effeminacy, emphasizes that the youth’s triumph could only be won via God’s intervention. This androgynous nudity is further confounded by sensual implications when observed up close—an experience presumably only available to wealthy guests of the palace.

A depiction of Eros riding a chariot adorns Goliath’s helmet, and a feather tenderly touches David’s inner thigh, both of which allude to concepts of passionate love.

Scholars have linked this sexuality to the Florentine fascination with youthful masculine beauty, which is evident in several works of art and drew the ire of Florentine pastors who termed it a vile aberration. The sword, helmet, and footwear are of contemporaneous Florentine fashion rather than biblical periods, implying a link to these renaissance preoccupations.

Of course, the biblical tradition included David’s beauty and appeal.

In Psalm 44, he is described as “most lovely among the sons of mankind,” and the name “David” was interpreted to signify “beloved.” To renaissance Florentines, the message would have been clear: Donatello’s David epitomizes desirability, he is favored by God, and this is the basis of his victory.

A Closer Look at Donatello’s David Statues

As discussed above, there are in fact two David statues created by Donatello. One is made from marble, and the other one is created from bronze. We will now take a closer look at both to understand the differences between the two.

The Marble David Sculpture

Donatello, who was in his 20s at the time, was contracted in 1408 to sculpt a statue of David to adorn one of Florence Cathedral’s buttresses, however, it was never installed. In the same year, Nanni di Banco was contracted to sculpt a marble statue of Isaiah at the same scale. One of the sculptures was hoisted into place in 1409, but it was discovered to be too tiny to be plainly seen from the ground and was removed; both sculptures then sat in the opera workshop for several years.

The Signoria of Florence ordered that the David be transferred to the Palazzo della Signoria in 1416; clearly, the youthful David was recognized as a potent political emblem as well as a religious hero.

Donatello was ordered to make some changes to the sculpture (perhaps to make him appear less like a visionary), and a pedestal with the inscription “To those who battle heroically for the fatherland, the gods offer help even against the most dreadful opponents” was built for it.

The marble is Donatello’s earliest known significant commission, David, and is a piece tightly connected to tradition, with little indications of the artist’s unique approach to the depiction that he would develop as he aged.

Although the legs are positioned in a traditional contrapposto, the figure stands in a beautiful Gothic sway inspired by Lorenzo Ghiberti. The face is blank (if one expects realism, but highly typical of the International Gothic style), and David appears almost ignorant of his defeated foe’s head resting between his feet. Some experts believe that the twist of the torso and the akimbo positioning of the left arm implies an element of personality – a kind of cockiness – yet the overall impact of the figure is fairly boring.

The young sculptor’s legitimately Renaissance curiosity in an ancient Roman type of mature, bearded head is sculpted with great confidence.

The Bronze Statue of David

The Donatello David bronze statue is well-known for being the first freestanding piece of bronze created during the Renaissance, and also the first freestanding nude male statue constructed since antiquity. It portrays David with a mysterious smile, posing with his foot on Goliath’s severed head shortly after slaying the monster. The adolescent is fully nude, but for a laurel-topped helmet and boots, and he wields Goliath’s sword. The work’s creation is undocumented.

The statue was commissioned by Cosimo de’ Medici, according to most scholars, but the period of its formation is uncertain and highly debated; suggested dates range from the 1420s to the 1460s, with the popular consensus recently having fallen in the 1440s when the new Medici Palace planned by Michelozzo was under development. According to one version, it was commissioned in the 1430s by the Medici family to be put on the grounds of the old Medici Palace.

Alternatively, it might have been built for that location in the new Palazzo Medici, where it was ultimately installed, putting the commission in the mid-1440s or later.

The sculpture is only mentioned in 1469. In 1494, the Medici dynasty was exiled from Florence, and the monument was relocated to the courtyard of the Palazzo della Signoria and ultimately to the Museo Nazionale del Bargello in 1865, where it still stands today. According to Vasari, the sculpture stood in the heart of the courtyard of the Palazzo Medici atop a column constructed by Desiderio da Settignano; an inscription appears to have highlighted the statue’s importance as a political monument.

A quattrocento book bearing the inscription’s wording is most likely an older reference to the monument; regrettably, the source is undated. Although a political context for the statue is largely agreed upon, what that significance is has been the subject of much discussion among academics.

The bronze David‘s symbolism is similar to that of the marble David: a youthful hero stands with a sword in hand and the severed head of his adversary at his feet. This statue, on the other hand, is strikingly different. David is physically fragile as well as extremely effeminate.

The head is claimed to be influenced by antique sculptures of Antinous, a Hadrian favorite known for his beauty.

The statue’s body, in contrast to the massive sword in hand, demonstrates that David slew Goliath not by physical skill, but through God. The nakedness of the boy adds to the notion of God’s presence since it contrasts with the highly armored behemoth. David is shown naked, as is usual for male nudists in Italian Renaissance paintings.

More Details on the Famous David Sculpture

Now that we have covered the differences between the two statues, we can go into further details. There are many controversies surrounding the statues. Many attempts have been made at proper identification as well as restoration.

Controversies

There is no evidence of contemporaneous replies to David. Nevertheless, the fact that the monument was put in Florence’s town hall in the 1490s implies that it was not considered contentious. The Herald of the Signoria noted the sculpture in an uncomfortable fashion in the early 16th century: “The David in the courtyard is not a faultless form since its right leg is distasteful.”

Vasari described the statue as “so lifelike” that it had to be recreated from life by the mid-century. However, there has been substantial debate among 20th- and 21st-century art historians regarding how to view it.

Goliath’s beard wraps around David’s sandaled foot, as though the youthful hero is dragging his toes through the hair of his slain opponent. Goliath is armed with a winged helmet. David’s right foot is securely planted on the small right wing, while the much longer left wing works its way up to his right leg to his crotch. The figure has been understood in several ways. One theory is that Donatello was gay and that he was expressing his sexual orientation through this monument.

Another interpretation is that the piece speaks to homosocial norms in Florentine society without reflecting Donatello’s own preferences. Nevertheless, sodomy was prohibited throughout the Renaissance, and over 14,000 men had been prosecuted in Florence for this crime, so this gay inference would have been deadly.

A further view is that David reflects Donatello’s attempt to create a new portrayal of the male nude, to use artistic license rather than reproduce the classical models that had previously served as the basis for depicting the masculine nude in Renaissance artwork.

Identification

Jeno Lanyi questioned the figure’s conventional identification in 1939, with an explanation veering toward ancient mythology, the hero’s helmet notably indicating Hermes or Mercury. Since then, a number of researchers have followed Lanyi’s lead, sometimes alluding to the monument as David-Mercury. If the figure is meant to represent Mercury, it is possible that he is standing on the head of the defeated giant Argus Panoptes.

All quattrocento sources to the sculpture, though, identify it as David.

Restoration

From June 2007 to November 2008, the bronze sculpture was restored. The statue had never been repaired before, but fears about layers of “mineralized waxings” on the surface of the bronze prompted the 18-month intervention. To help remove build-up, the sculpture was scraped with scalpels in non-gilded regions and laser-lasered in gilded sections.

Influence and Copies

The Victoria and Albert Museum in London has a full-size plaster cast of a shattered sword. A full-size white marble replica may also be seen at the Temperate House in the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Surrey, a few miles outside of downtown London. Aside from the copies in the UK, there is also another version in the Slater Museum at the Norwich Free Academy in Norwich, Connecticut, USA.

Donatello’s bronze statue of David was perhaps his most famous work – and one of the finest sculptural masterpieces of the early Renaissance. This work heralds the rebirth of the nude statue in the round figure, and it is one of the most significant achievements in the history of western art since it was the first of its kind in over a thousand years. The repercussions of this occurrence are depicted here, with David standing in a meditative position with one foot over his enemy’s severed head. David is dressed in only boots and a shepherd’s cap with laurel leaves on top, which might refer to his victory or to his vocation as a musician and poet.

Take a look at our David by Donatello webstory here!

Frequently Asked Questions

Who Is Depicted in the David Sculpture?

The subject of this sculpture is David, the hero of the Bible, who as a young man slew the Philistine giant Goliath and set his people free. In Donatello’s sculpture, David’s youth is evident: his nude body is that of a youngster, vividly contrasted with Goliath’s heavy beard and age, whose severed head falls at his feet. David’s vulnerability is highlighted by the stone he grips in his left hand, a reminder that, while brandishing a sword, he brought down his massive opponent with a single slingshot.

Why Is the Statue of David Naked?

In the ancient arts, being shown completely naked had positive connotations: ancient Greek and Roman deities and heroes transmitted their inner purity via idealized naked bodies. Donatello follows this old tradition by portraying David as a nude man. David’s nudity would have been seen by Renaissance Christians as a step forward from the previous norm, heroizing a Judeo-Christian person rather than a pagan one. This takes us to another crucial aspect of the work: its initial placement atop a tall column. His frail appearance underscores the extraordinary magnitude of his victory. In front of God and the crowd, David is almost stripped naked, triumphant purely due to God’s will.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Donatello “David” – Looking at Donatello’s Two “David” Sculptures.” Art in Context. May 13, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/donatello-david/

Meyer, I. (2022, 13 May). Donatello “David” – Looking at Donatello’s Two “David” Sculptures. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/donatello-david/

Meyer, Isabella. “Donatello “David” – Looking at Donatello’s Two “David” Sculptures.” Art in Context, May 13, 2022. https://artincontext.org/donatello-david/.