“The Holy Trinity” Masaccio – Dawn of the Renaissance

The Holy Trinity by Masaccio is regarded as one of the most iconic artworks of the Renaissance period. The Holy Trinity painting is located in Florence in the Dominican Church of Santa Maria Novella. The Trinity artwork was so influential and impactful that many people such as Giorgio Vasari assumed that the artwork contained some sort of optical illusion which created the painting’s incredible depth and perspective.

An Introduction to Masaccio the Painter

Masaccio the painter is often regarded as the very first true Renaissance artist. His terribly brief life ended his growth prematurely, yet his remarkable work changed the trajectory of art in the western world. Masaccio was able to reap the benefits of the rich patrons’ enormous funding of the arts during the Early Renaissance, who were eager to flaunt their money and rank in the shape of friezes and altar-pieces decorating private chapels.

Very little was documented about his lifetime; what is understood is that Masaccio’s paintings were not like that of any other painter active in Florence at that period, employing a logical method that would come to define the Renaissance as a whole.

An illustration of Masaccio from Giorgio Vasari’s Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects (1550); Giorgio Vasari, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The employment of linear perspective to give the appearance of depth in a two-dimensional portrayal was one of the most fundamental developments in painting – and no less in engineering and architecture – during the Renaissance period.

Masaccio was inspired by Filippo Brunelleschi’s architecture, who had recovered the notion of perspectives, which had been forgotten since the Ancient Greco-Roman eras, and adapted it to his paintings, changing the direction of art in the western sphere.

Masaccio’s paintings displayed astonishing realism that was radically distinct from any other artwork of the period by adopting the concepts of viewpoint from architectural design and the analysis of lighting and structure from sculpting and adapting them to paintings.

His holy figures appear as three-dimensional objects. They inhabit an augmentation of the viewer’s environment, as if behind some kind of glass pane, instead of a completely different, visual plane, as observed in Medieval art. The naturalism of Masaccio the painter’s artworks not only illustrates scientific concepts that were critical to the advancement of the Renaissance, but it also brings the sanctified individuals closer to the observer and makes them look more compassionate, creating a change in the balance between the individuals and their Deity.

The Holy Trinity by Masaccio

| Date Created | c. 1425 – 1428 |

| Artist | Masaccio (1401 – 1428) |

| Medium | Fresco Mural |

| Current Location | Santa Maria Novella |

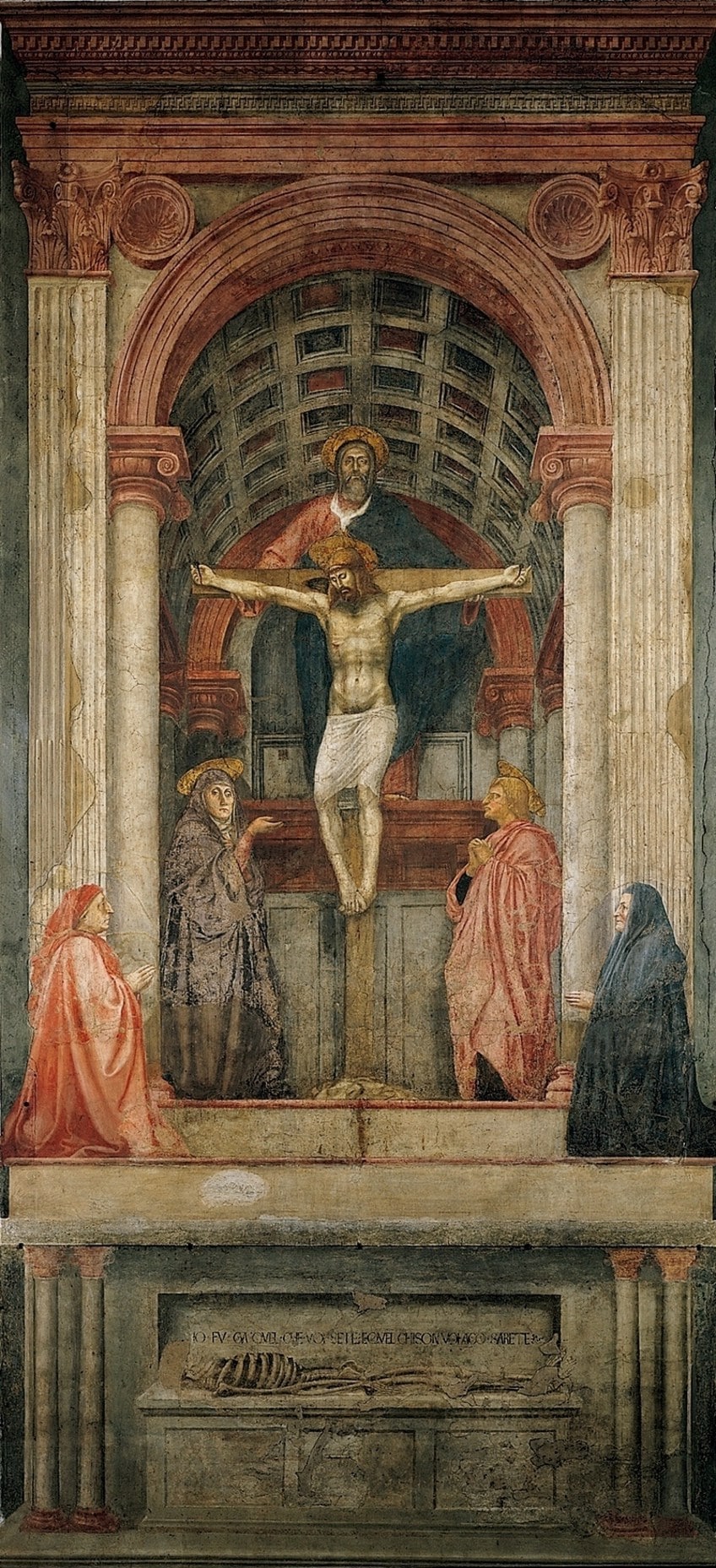

The Holy Trinity painting is one of Masaccio’s most important artworks. It can be viewed at its permanent location in Florence at the Dominican Church of Santa Maria Novella. The Holy Trinity artwork is believed to have been produced at some time between 1425 and 1427. It was one of the last of Masaccio’s paintings to be produced before his early death at the age of 27.

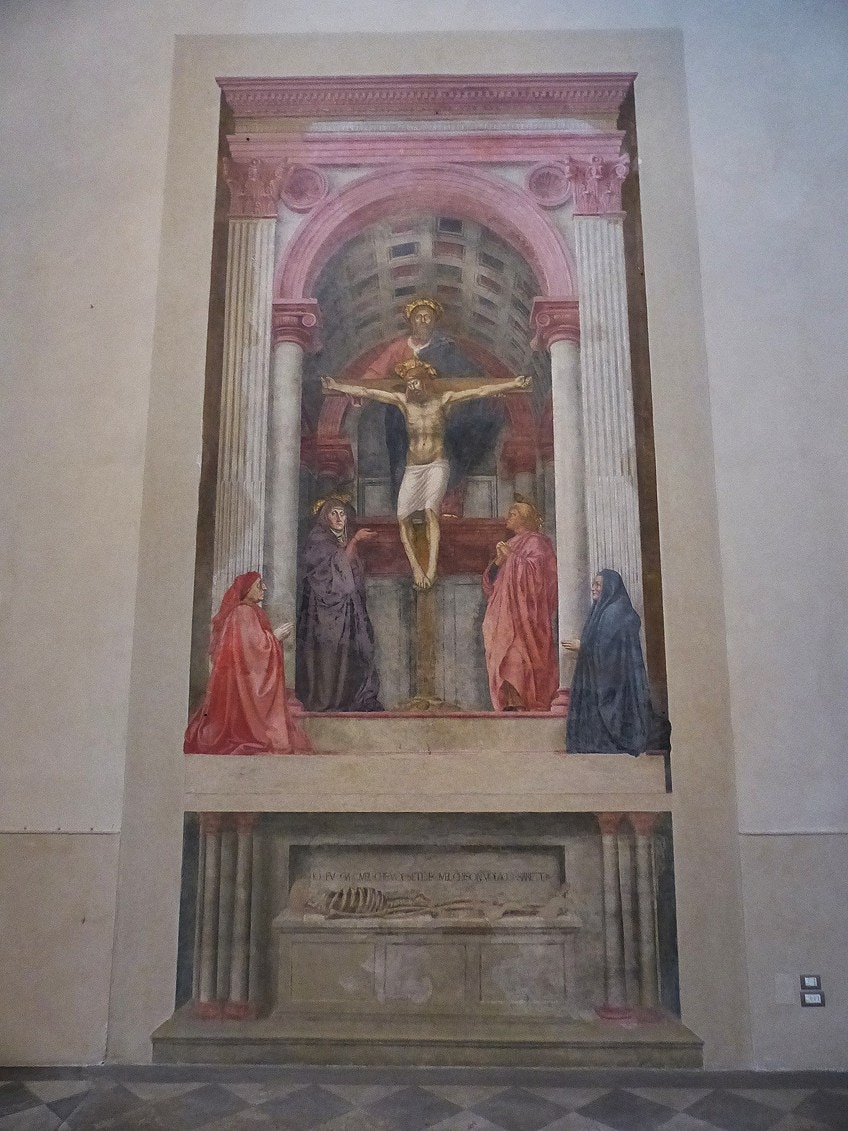

Location of The Holy Trinity Painting

The painting may be seen in the center of the left aisle of the basilica. Even though the layout of this area has significantly changed since the work of art was initially created, there is good evidence that the mural was matched very accurately in connection to the visual range and viewpoint configuration of the room at the moment, especially a defunct entrance-way facing the artwork, in order to improve the trompe-l’œil effect.

An altar, erected as a shelf between the top and the bottom portions of the mural, added to the “realism” of the piece.

Donors and Commissioners of The Holy Trinity Painting

Little is documented about the commission’s specifics; no contemporary documentation indicating the altar-patron(s) piece’s have been discovered. The two donor images seen in the fresco (one on each side of the arch) have yet to be officially identified. The people represented are almost definitely contemporaneous Florentines; either the people who sponsored the painting or family or close friends of the people portrayed.

According to the recognized norms of such portrayals, it is commonly considered (but not unanimously) that they were most likely still alive at that point the painting was commissioned.

Evidently, the depictions in the artwork are quite exact similitudes of their true looks at the moment their images were produced. The major speculations about their identification point to two local households: the Lenzi family or, for a minimum one of the characters, a relative of the Berti family, a working clan from Florence’s Santa Maria Novella district.

According to newly found Berti household documents, they possessed a grave at the foot of the painting, and it has been proposed that they had a special “spiritual allegiance” to the worship of “The Holy Trinity” artwork.

Other references acknowledge a Lenzi crypt close to the altar with the epitaph “Domenico di Lenzo, et Suorum 1426,” and other Lenzi family decorations in the chapel at that time, and presume the donor portrayals are posthumous portraits of Domenico, premised on the full-profile poses used for the characters.

Domenico’s death, as documented, would have occurred on the 19th of January in 1427, according to the Florentine date format of the time. Considering the transition from Julian to Gregorian timetables, Domenico’s passing would have occurred on the 25th of March in 1427, according to the date format of the period.

It has been speculated that Filippo Brunelleschi was instrumental, or at the very least advised, in the conception of the “Trinity” artwork.

Brunelleschi’s expertise on linear perspectives and design undoubtedly influenced the painter, as seen by Massacio’s paintings. Another individual, Fra’ Alessio has been named as responsible for his contribution posited primarily in terms of the right representation of the Holy Trinity painting in accordance with the Dominican order’s tastes and sensibility.

The Work of Cosimo I and Giorgio Vasari

In approximately 1568, the Duke of Florence, Cosimo I, instructed Giorgio Vasari to perform substantial repair operations at the Santa Maria Novella in accordance with the preferences and ecclesiastical politics of the day. The chapel area in which Masaccio’s painting was placed was reconfigured and redecorated as part of this restoration.

Giorgio Vasari had already written about Masaccio, giving a glowing endorsement of this particular piece.

When it finally came to renovate the chapel housing Trinity, around 1570, Vasari elected to keep the mural undisturbed and build a new altar and screens in front of Masaccio’s painting, leaving a tiny gap and successfully hiding and safeguarding the older work.

While it appears that Vasari intended to conserve Masaccio’s painting, it is unknown to what degree Duke Cosimo or other “interested individuals” were engaged in this choice. Vasari created a Madonna of the Rosary to adorn the new altar; the artwork still exists but has been relocated within the building.

The Rediscovery of the Holy Trinity by Masaccio

After Vasari’s altar was demolished during repairs in 1860, Masaccio’s Holy Trinity was unearthed. The Crucifixion, the upper portion of the mural, was eventually moved to canvas and placed in a separate section of the cathedral. According to existing accounts, it is uncertain if the lowest portion of the mural, the cadaver tomb, was intentionally deleted (and probably plastered over) during the 1860s remodeling projects.

At the time, the Crucifixion part of the artwork was restored to substitute missing design features, primarily architectural aspects around the circumference of the piece.

While the artwork was in a poor state when it was discovered, it is also possible that the transference from the wall to canvas caused more harm. The cadaver tomb half of the piece was recovered in situ in the 20th century, and the two halves were once again united in their intended place in 1952. From 1950 to1954, Leonetto Tintori worked on the integrated whole to repair it.

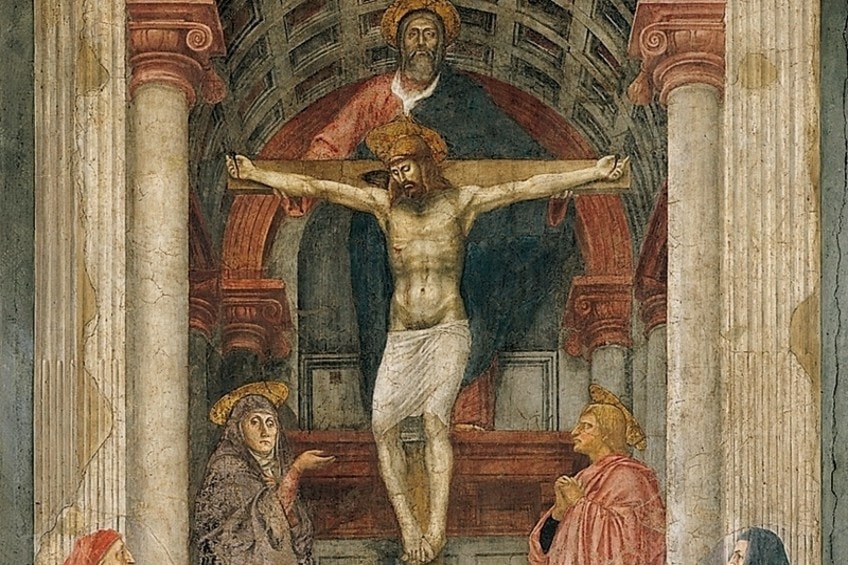

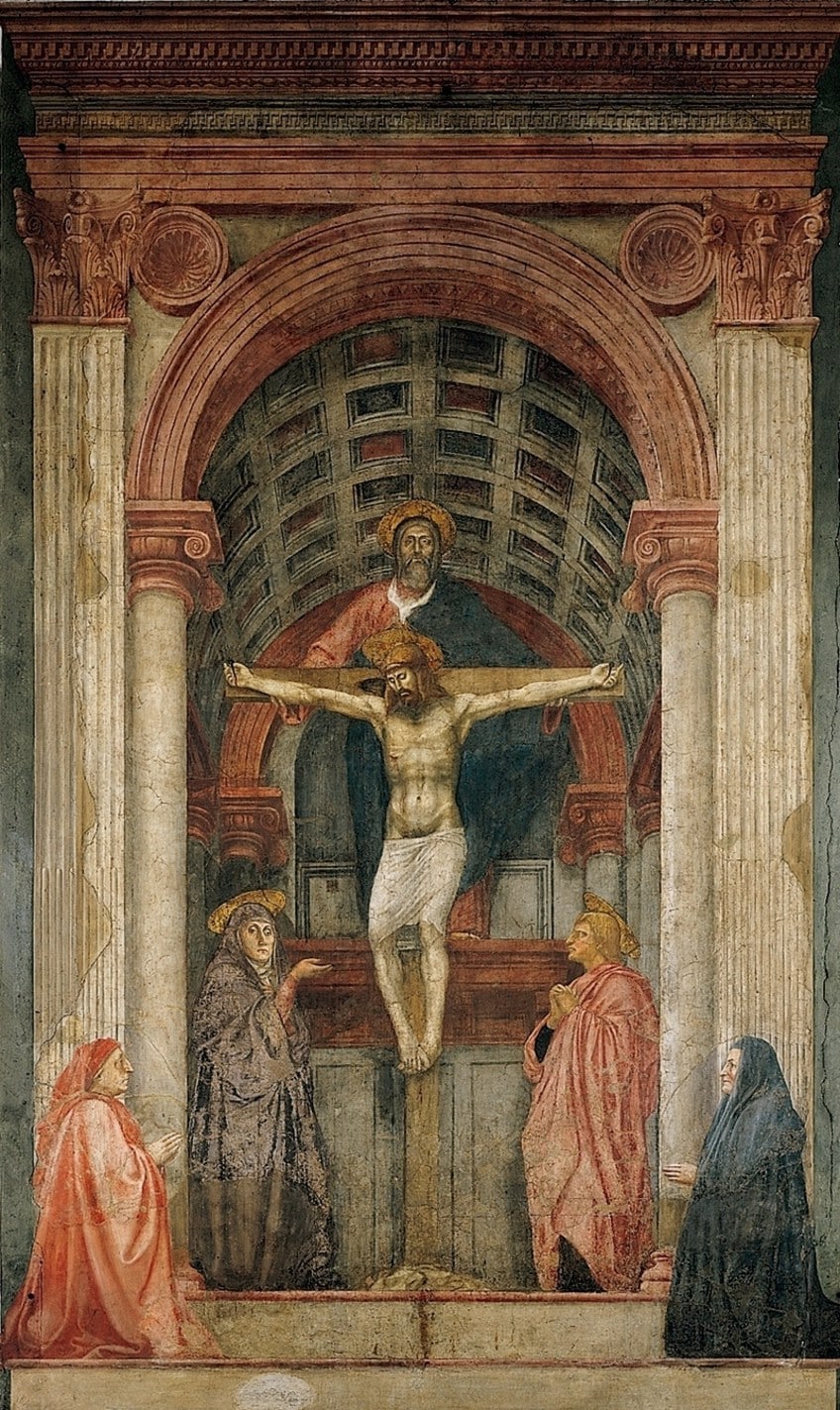

Description of The Holy Trinity by Masaccio

The picture is roughly around 317 cm broad by 667 cm tall. This results in an average vertical-to-horizontal ratio of roughly 2:1. The top and bottom portions of the piece are generally proportioned to 3.1. Initially, the design also had an actual ledge that was utilized as an altar, literally jutting outwards from a now blank zone between the top and the bottom portions of the painting, adding to the artwork’s feeling of dimension and authenticity.

The altar table, built as a columned shelf 5 feet above the ground and believed to be 60 cm broad, would have been designed to match and compliment the decorated architecture.

Its facing-edge and top surface blend with the fresco’s stairs and arch; and its sustaining pillars, both real and imaginary, blend with the shadows cast by the overhanging to produce a crypt-like illusion for the tomb underneath.

The upper half of the mural still bears the remains of candle soot and heat damage from the altar’s operation. The depicted figures are almost life-size. An adult of medium height facing the picture would have had their eye-line just above the floor with Death in the shape of the tomb and skeleton squarely across from them, and the prospect of Salvation above.

The mural has been destroyed and repaired over the passage of time and occurrences.

Much of the outside margin of the upper section, primarily architectural detail, is restoration work. Other portions of “new” painting can be distinguished by changes in color, visual roughness, and texture; and in some cases, by visible “fractures” along the border between the initial painting surface and sections of the composition where the old surface is completely removed and was recreated.

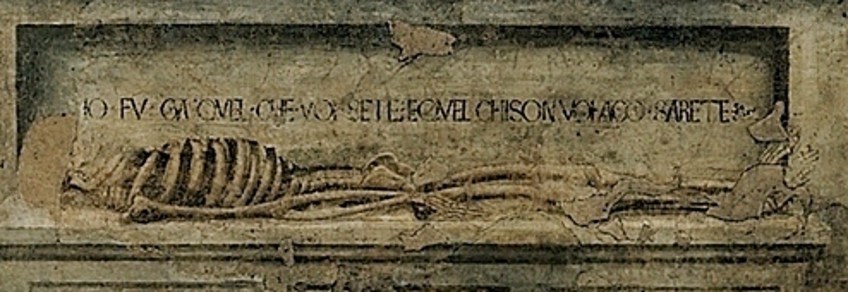

The skeleton is a memento mori or remembrance of death. The lower part, which depicts a memento mori in the shape of a cadaver tomb, has likewise lost a substantial amount of painting, although the repair effort has been more controlled and less comprehensive. This is most likely owing to the reality that the lower half of the painting was not discovered until the mid-20th century.

By this period, “common procedure” in restorations had grown more cautious, with a greater focus on conserving and disclosing the original idea or concept, whereas previous repairs appeared to be more focused on making a visually acceptable “reproduction” of the painting. According to existing sources, no sizable Roman vaulted barrel, Triumphal arch, and otherwise, had been built in Western Christendom ever since late antiquity at the moment this artwork was painted.

The picture represents Christ’s execution, with the traditional images of the Virgin and St John at the base of the crucifix. Nevertheless, the image breaks Renaissance tradition in so many aspects that it has remained a mystery for centuries, despite being researched by historians. The picture is known as The Trinity because it depicts Jesus with God behind him and the Holy Ghost as a small white dove flying between them.

Although depicting God figuratively was not religiously prohibited at the time, he would have been represented in a non-earthly domain, symbolizing the skies, instead of in the physical space of the building.

This painting’s representation of a three-dimensional landscape is often regarded as the apex of Masaccio’s artistic expertise. The viewpoint is so realistic that current researchers have been able to create a 3D representation of the imaginary space described in the picture using digital technology.

Masaccio’s outstanding draughtmanship allows him to produce such a lifelike environment, giving the observer the impression that the crucifixion is taking place directly in front of their eyes, in the cathedral itself. This gives the depiction an intensity that immediately unites the observer with Christ’s agony, not only as a God but as a normal human being.

Notable Characteristics of the Holy Trinity Artwork

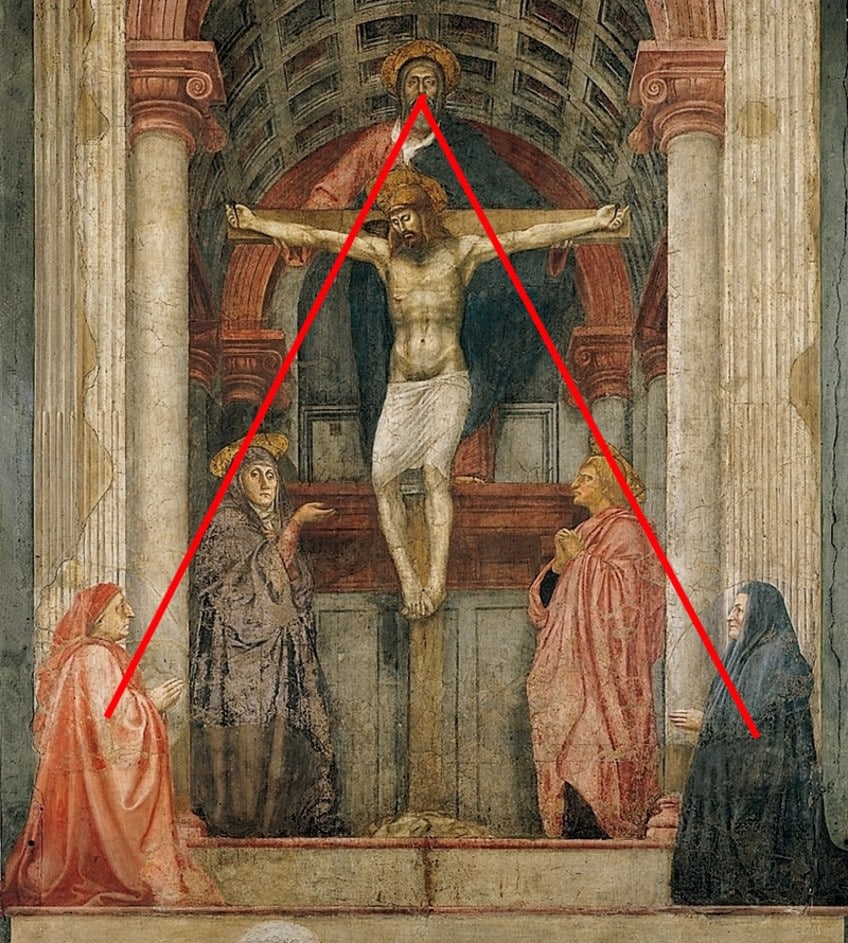

The Holy Trinity painting is notable for its ideas taken from ancient Roman arches and stringent compliance to newly invented point of view methods, with a vanishing point at the audience’s eye height, so that, as Vasari characterizes it, “a vault stretched in perspective, and split into squares with rosettes that reduce and are stylized so well that there appears to be a hole in the wall.” This creative style is known as trompe-l’œil, which translates as “misleads the sight” in French.

Decades of Florentine artists and visiting painters were influenced by the painting.

The magnificent God holding the Cross, regarded as an unfathomable deity, is the only figure lacking a completely realized three-dimensional occupancy of space. Another significant innovation is the presence of kneeling guests in the audience’s own space, “in front of” the image plane, which is defined by the columns and pilasters from which the barely concealed vault would seem to emerge.

They are represented in the conventional prayerful posture of donor images, but on the same magnitude as the main figures instead of the more usual diminutive technique and with notable attention to naturalism and depth.

Masaccio draws a horizon line across the ground on which the two benefactors are crouching. These are the people at the farthest opposite extremes of the spectrum. The orthogonal lines extend upward from the horizon’s vanishing spot. They spread geometrically upwards as well as outwards to form the angles and proportions of the vault’s somewhat diagonal planes.

The use of linear perspective creates the sense of genuine space that goes backward in actual depth.

The vast scale of over 22 feet by 10.5 feet contributes to the idea of Masaccio’s setting in this piece. Masaccio encases his people in what appears to be a proportional and exact picture of a genuine setting, using Brunelleschi’s revolutionary approach of recreating the impression of a realistic environment.

Interpretations of The Holy Trinity Painting

The fresco has been interpreted in a variety of ways. Most academics see it as a classic type of artwork, designed for personal acts of worship and memorials to the deceased, however, theories of how the artwork represents these purposes vary in depth.

The imagery of the Trinity, accompanied by Mary and John or includes donations, is prevalent in late 14th and early 15th-century Italian artwork, as is the relationship of the Trinity with a grave.

Nevertheless, no prototype for the identical imagery of Masaccio’s painting, integrating all of these components, has been found. The patrons’ figures have most frequently been interpreted as relatives of the Lenzi line or, subsequently, a relative of the Berti clan of Florence’s Santa Maria Novella area. They function as theological devotional models for audiences, but since they are nearer to the sacred beings than the spectators are, they also acquire unique significance.

The tomb is made up of a sarcophagus that houses a skeleton. Carved into the wall above the corpse is an engraving that reads, “I was once what it is you are, and which I am you will also be.” This memento mori emphasizes that the artwork was made to teach the audience something.

At the most basic level, the picture must have implied to the 15th-century devout that, because they would all perish, only their trust in the Trinity and Christ’s death would allow them to transcend their transient realities. As per American art scholars, the painting, with its dreadful rationality, is like a demonstration in philosophy or arithmetic, with the Heavenly Father, with His unwavering eyes, serving as the premise from which all else flows inevitably.

And that wraps up our look at “The Holy Trinity” by Masaccio. The Holy Trinity artwork, one of the most prominent pieces of Renaissance art, may be viewed in Florence’s Dominican cathedral of Santa Maria Novella. It features a secular element, as do many sacred artworks painted in Florence throughout the Renaissance. Its the artist’s application of single-point linear viewpoint to structure its arrangement is what made it one of the 15th century’s most significant Renaissance masterpieces.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why Is the Holy Trinity Painting So Important?

This artwork’s representation of three-dimensional geometry is often regarded as the apex of Masaccio’s specialist knowledge. The perspectives are so realistic that current researchers have been able to create a 3D representation of the imaginary space described in the picture using digital technology. Masaccio’s superb techniques allowed him to depict such a realistic environment, providing the impression that the crucifixion is taking place directly in front of their eyes, in the cathedral itself. This gives the image an immediacy that immediately unites the observer with Christ’s suffering, not only as a God but as a fellow human being.

What Is the Trinity Artwork About?

The figure is reminiscent of an older painting in which the Parent of Christ is portrayed with her own parent standing beside her. The representation of God as a Parent standing behind his son enables the spectator to connect to the Holy Trinity on a more personal level, which was a daring move at a period when the Catholic Church maintained a tight hierarchy that claimed the people could only communicate with God through clergy appointed by the Church. It alludes to the new humanistic era in art and ideas that were starting to emerge with the Early Renaissance. The imaginary design of the place, on the other hand, includes degrees of detachment. God is over and behind Christ, who is above the apostles; the contributors are near to God because of their giving to the church; and the observer is well below the picture, gazing in. A realistic depiction of a tomb with a skeleton laying on atop of it is at eye level and ‘or underneath’ the artwork’s imaginary foundation. The line “I used to be what it is you are, as well as what I am you shall be” is etched onto the monument in Italian. As they look up at the picture of Christ suffering for their redemption, the audience is reminded of their own death.

Who Was Masaccio the Painter?

Masaccio the painter is often considered to be the first authentic Renaissance artist. His remarkably shortened life cut short his development, yet his outstanding achievement altered the course of art in the Western world. Masaccio benefited from the affluent patrons’ massive support of the arts during the Early Renaissance, who were keen to showcase their wealth and status in the form of friezes and altar-pieces decorating private chapels. Little is known about Masaccio’s life; what is known is that his paintings were unlike those of any other painter functioning in Florence at the time, utilizing a logical style that would come to characterize the Renaissance as a whole.

Alicia du Plessis is a multidisciplinary writer. She completed her Bachelor of Arts degree, majoring in Art History and Classical Civilization, as well as two Honors, namely, in Art History and Education and Development, at the University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. For her main Honors project in Art History, she explored perceptions of the San Bushmen’s identity and the concept of the “Other”. She has also looked at the use of photography in art and how it has been used to portray people’s lives.

Alicia’s other areas of interest in Art History include the process of writing about Art History and how to analyze paintings. Some of her favorite art movements include Impressionism and German Expressionism. She is yet to complete her Masters in Art History (she would like to do this abroad in Europe) having given it some time to first develop more professional experience with the interest to one day lecture it too.

Alicia has been working for artincontext.com since 2021 as an author and art history expert. She has specialized in painting analysis and is covering most of our painting analysis.

Learn more about Alicia du Plessis and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Alicia, du Plessis, ““The Holy Trinity” Masaccio – Dawn of the Renaissance.” Art in Context. November 28, 2021. URL: https://artincontext.org/the-holy-trinity-masaccio/

du Plessis, A. (2021, 28 November). “The Holy Trinity” Masaccio – Dawn of the Renaissance. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/the-holy-trinity-masaccio/

du Plessis, Alicia. ““The Holy Trinity” Masaccio – Dawn of the Renaissance.” Art in Context, November 28, 2021. https://artincontext.org/the-holy-trinity-masaccio/.