What Is Iconography? – In-Depth Definition, Examples and History

What is Iconography in art? Iconography art history is the study of the classification, description, interpretation, and characterization of image content. It entails the examination of the subjects represented, the specific compositions and features employed, and other characteristics distinct from the aesthetic style of the artwork.

What Is Iconography?

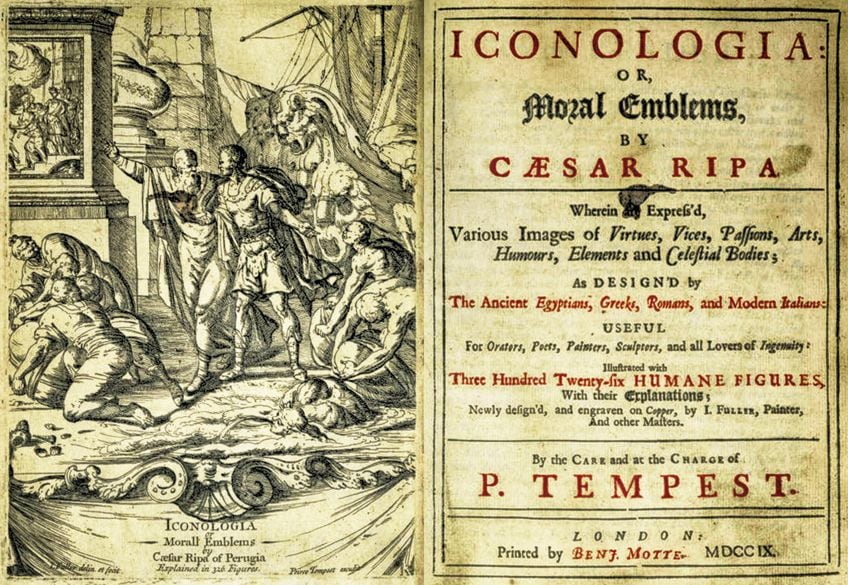

Giorgio Vasari, an early Western artist who devoted much time to studying the content of paintings, said that he could not always interpret the artworks in the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence, encouragingly proving that such artworks were challenging to grasp even for well-informed contemporary artists of the period. Cesare Ripa’s publications, such as his emblem handbook Iconologia (1593), were less well-known, although having inspired poets, artists, and sculptors for nearly 200 years following their publication. A 17th-century biographer of contemporary painters named Gian Pietro Bellori described and analyzed several paintings – usually not very accurately.

The Foundations of Iconography Art History

Iconography as an intellectual art history field of study emerged in the 19th century through the writings of academics such as Anton Heinrich Springer, Adolphe Napoleon Didron, and Émile Mâle, all of whom were experts in Christian religious paintings, which was the primary topic of study during this era, in which French academics were particularly prevalent. They turned to earlier attempts to categorize and arrange subjects encyclopedically, such as Anne Claude Philippe de Caylus’ and Cesare Ripa’s publications, as guides to interpreting works of art, both holy and secular, in a more scientific way than the prevalent aesthetic perspective of the time.

These initial works opened the way for encyclopedias, guides, and other books that aid in the identification of art elements.

Iconography in the 20th Century

Aby Warburg and his students Erwin Panofsky and Fritz Saxl developed the discipline of identifying and categorizing themes in images to use iconography as a way of interpreting meaning in early 20th Germany. In his book Studies in Iconology (1939), Panofsky formalized an impactful methodology to iconography, defining it as the division of art history concerned with the subject or interpretation of artworks, as contrasted to form. However, the differences he and other academics tried to draw between specific interpretations of “iconography” (the characterization of content), and “iconology” (the examination of the significance of that content), have not been widely accepted, although a few scholars still use the terms. Students such as Meyer Schapiro and Frederick Hartt continued to study under Panofsky’s tutelage in the United States, where he relocated in 1931.

Richard Krautheimer, an expert on medieval churches and also a German émigré, expanded iconographical examination to include architectural forms in an influential work, Iconography of Mediaeval Architecture (1942). Iconography was extremely popular in art history throughout the 1940s. While much iconographical research remains complex and specialized, some studies, such as Panofsky’s thesis that the text on the back wall of Jan van Eyck’s Arnolfini Portrait (1434) transformed the artwork into a record of a contract of marriage, started to gain a far larger audience. Holbein’s The Ambassadors (1533) has been the focus of publications for a broad audience with innovative hypotheses about its iconography, while Dan Brown’s best-sellers include discredited claims about the iconography of paintings by Leonardo da Vinci.

Technological improvements enabled the creation of massive collections of photos with an iconographic order or directory, such as the Warburg Institute’s and Princeton’s Index of Medieval Art.

These are currently being digitized and released online. The Iconclass system, an extremely complicated way of categorizing the contents of images, with 28,000 classification kinds and 14,000 search terms, was created in the Netherlands as a routine categorization for recording archives, with the notion of gathering huge databases that will enable the recall of images depicting specific details, topics, or other attributes.

Types of Iconography in Art

There are two kinds of iconography in art: religious and secular. All major world religions, including Abrahamic and Indian faiths, employ religious pictures to some degree, and they frequently contain very complicated iconography that represents centuries of collective history. Later, secular Western imagery drew on similar motifs.

The Iconography of Indian Religions

Mudra, or movements with distinct meanings, are central to the iconography of Indian faiths. Other characteristics include the halo and aureola, which may also be seen in Islamic and Christian art, as well as divine powers and traits symbolized by asana and ceremonial objects like the sauwastika, dharmachakra, danda, and phurba. Other aspects include the symbolic use of color to signify the Classical Elements, as well as letters and bija words from holy alphabetic scripts. Tantra influenced art to acquire esoteric meanings available only to initiated; this is a particularly significant element of Tibetan art.

The artwork of Indian religions, such as Hinduism, is controlled by sacred books known as Aagama, which explain the ratios and proportions of the icon, known as taalmaana, as well as the emotion of the dominant figure in a setting.

For instance, though regarded as a wrathful god, Narasimha, an avatar of Vishnu, is represented in a pacified attitude in a few settings. Although iconic portrayals of a single individual are the most common type of Buddhism image, large fresco or stone relief narrative stages of the Buddha’s life can be found at major sites such as Ajanta, Sarnath, and Borobudur, particularly in earlier periods. In contrast, narrative sequences in Hindu artwork have become more prevalent in recent years, particularly in miniature paintings depicting the lives of Rama and Krishna.

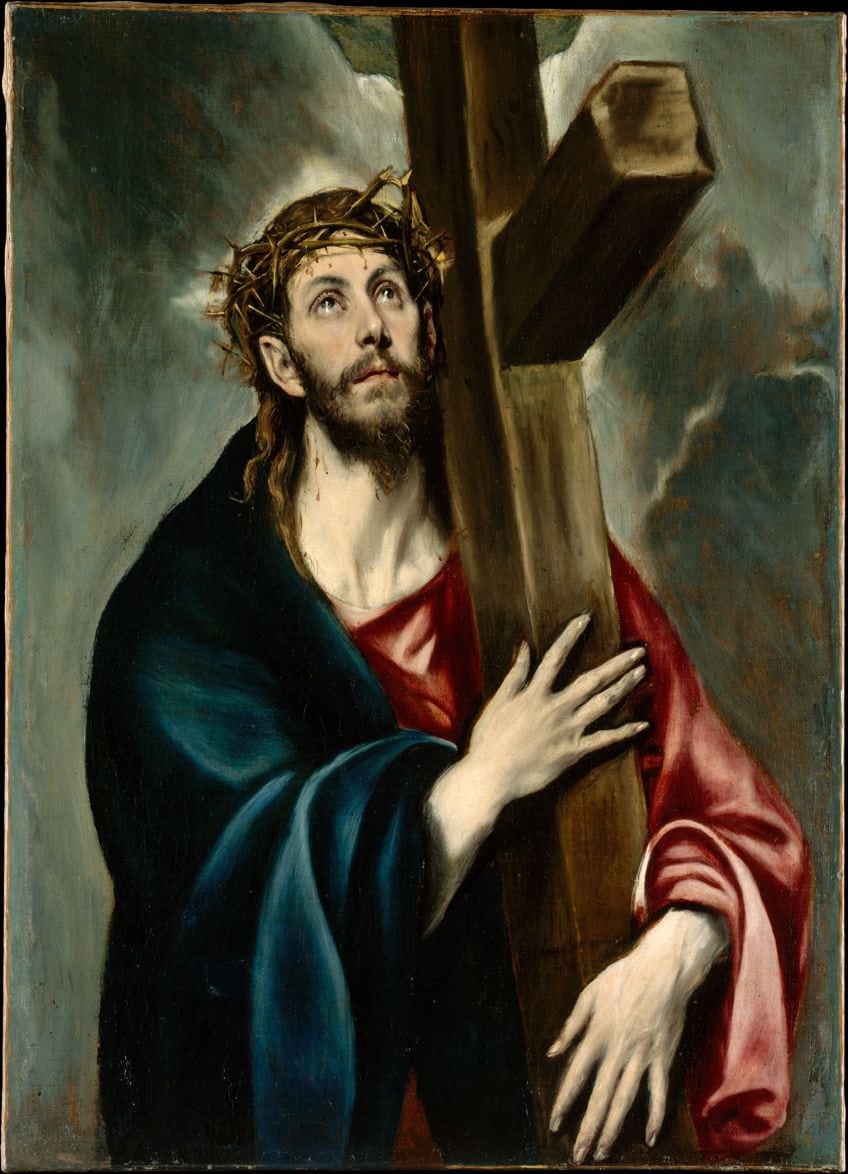

The Iconography of the Christian Religion

Christian art incorporates Christian iconography, which was extensively developed throughout the medieval and Renaissance periods, and is an important component of Christian media. Aniconism was abandoned from the beginning of Christian theology, and the creation of early Christian architecture and art took place during the first 200 years following Jesus. In the Catacombs of Rome, little images depict orans figures, portraits of Christ and certain saints, and a limited amount of “abbreviated renderings” of biblical stories stressing rescue.

Monumental artwork borrowed themes from Roman Imperial iconography, ancient Greco-Roman religion, and popular artwork beginning with the Constantinian period – the image of Christ in Majesty derives something from both Royal portraits and Zeus portrayals. Although numerous holes in the canonical Gospel tales were filled with material from the apocryphal gospels, iconography started to be regulated and connect more accurately to Biblical texts in the Late Antique era. Most of them were eventually weeded out by the Church, but others remained, such as the oxen and donkey in the Nativity of Christ. Although numerous holes in the canonical Gospel tales were filled with material from the apocryphal gospels, iconography started to be regulated and connect more accurately to Biblical texts in the Late Antique era.

Most of them were eventually weeded out by the Church, but others remained, such as the oxen and donkey in the Nativity of Christ. Iconographic innovation was seen as harmful, if not blasphemous, in the Eastern Church after the time of Byzantine iconoclasm, albeit it continued at a diminishing rate. Traditional images were generally thought to have genuine or supernatural origins, and the artist’s goal was to imitate them with as little variance as possible. The Eastern church likewise refused to utilize large free-standing sculpture because it was too suggestive of paganism.

Numerous iconic kinds of Christ, Mary, saints, and other topics were established in both the East and the West; the number of identified varieties of icons of Mary, with or without the newborn Christ, was exceptionally enormous in the East, whilst Christ Pantocrator was the most prevalent image of Christ.

The Panagia and Hodegetria forms of Mary are particularly significant. Traditional templates for narrative paintings arose, including huge cycles depicting events from the Virgin’s Life, Christ’s Life, sections of the Old Testament, and, increasingly, the lives of prominent saints. A system of characteristics emerged, particularly in the West, for distinguishing specific images of saints by a standardized appearance and symbolic items carried by them; in the East, they were more inclined to be recognized by text labels.

From the Romanesque era onwards, sculpture on religious institutions became progressively significant in Western artworks, and, due to the absence of Byzantine models, became the spot of much iconographic advancement, alongside the illuminated manuscripts, that had earlier taken a decidedly distinct direction from Byzantine counterparts, under the impact of Insular artwork and other influences. Many changes were caused by advancements in theology and devotional activity, such as the theme of the Assumption and the Coronation of the Virgin, both of which were linked with the Franciscans. Most artists were satisfied to imitate and somewhat adapt the creations of others, and it is apparent that the priests, for whose buildings most artworks were commissioned, frequently described in considerable detail what they wanted to be portrayed.

The theory of typology, according to which the significance of most Old Testament events was comprehended as a foreshadowing of an incident in the life of Jesus, was frequently echoed in art, and in the later medieval period came to influence the preference of Old Testament images in Western Christian paintings. By the 16th century, ambitious painters were required to discover original compositions for each topic, and explicit borrowing from earlier painters is more typically employed in the individual figures’ stances than the full compositions.

The Protestant Reformation quickly limited most Protestant religious art to Biblical subjects imagined along the lines of historical painting, while the Catholic Council of Trent, after many decades, considerably limited the flexibility of Catholic painters.

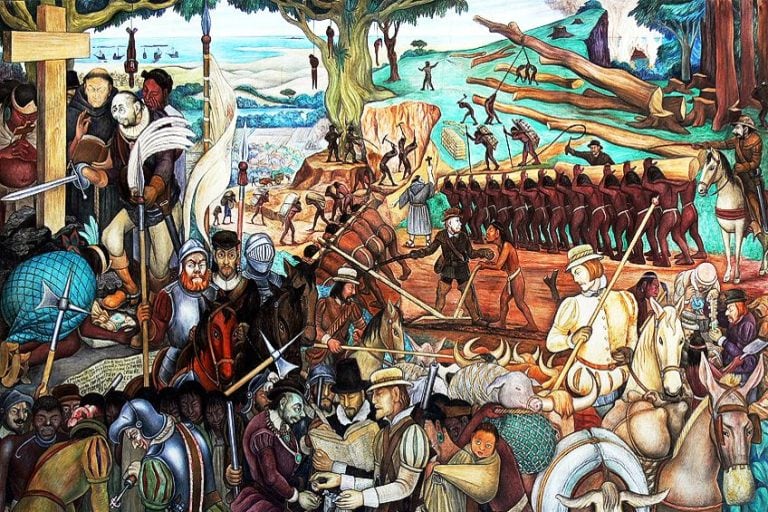

The Iconography of Western Secular Art

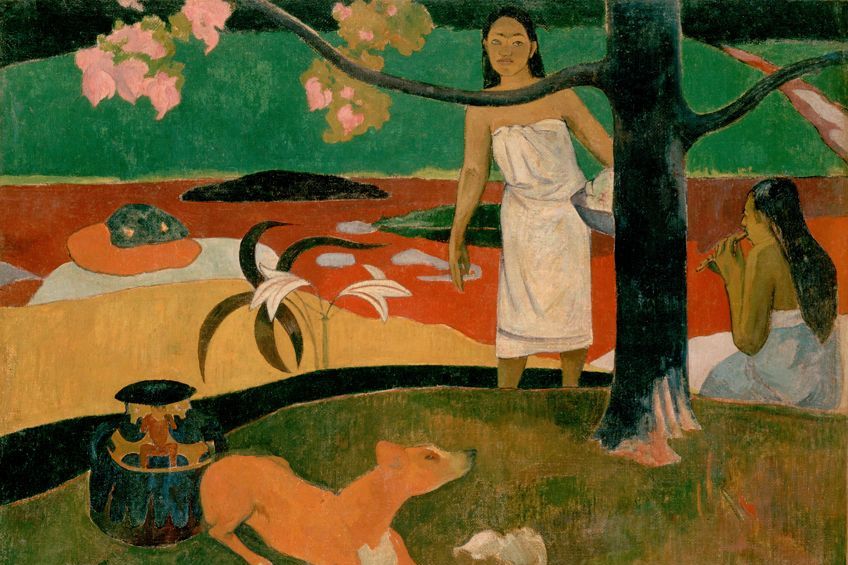

From the Renaissance onwards, secular artwork became far more widespread in the Western world, developing its own culture and norms of iconography, in historical paintings (which include portraits, mythologies, genre scenes, and even landscapes), and in modern media and genres (such as cinema, political cartoons, photography, anime, and comic books). In principle, Renaissance mythological art was resurrecting Classical Antiquity’s iconography, but in fact, motifs like Leda and the Swan developed on wholly unique lines, and for distinct objectives. Personal iconographies, in which works appear to have profound meanings unique to the artist and maybe only apparent to the artist, date back at least to Hieronymus Bosch but have grown in importance with artists such as William Blake, Francisco Goya, Pablo Picasso, Paul Gauguin, Joseph Beuys, and Frida Kahlo.

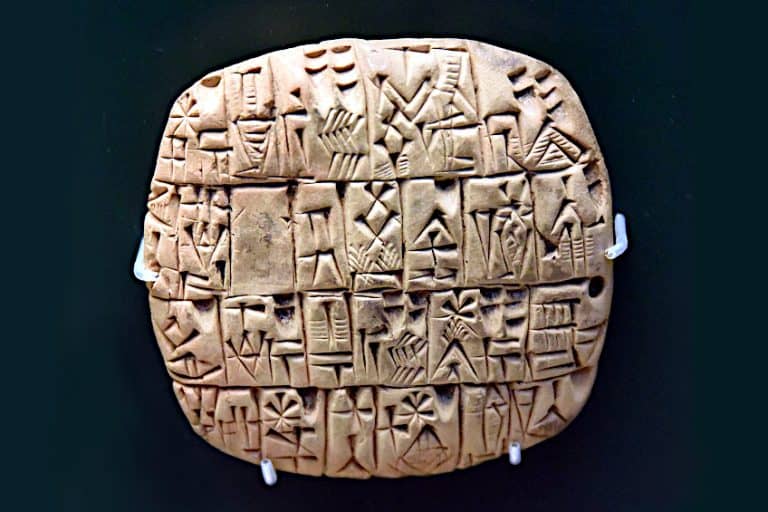

To comprehend iconography in art, we must first consider what icons and symbols are. The employment of representations has been organically mirrored in Mankind’s daily existence since the dawn of time. Symbols, signs, and icons of many types have long been used as one of the most efficient means of communication. Icons and symbols can have varied meanings depending on the circumstances of the piece, its position, or the person analyzing it, but the majority of them have the same general meaning. The usage of one or more symbols in an artistic environment also serves the objective of conveying a certain message.

Take a look at our Iconography webstory here!

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is Iconography Art History?

Many scholars and critics often dedicate themselves to studying the styles, techniques, and aesthetic qualities of a particular artwork. However, the artist often uses more than just techniques to impart a message. Very often the objects and subjects that appear in artworks have not just been placed there to look pretty – they are also meant to convey a specific meaning to the people viewing them. But what do they mean? Well, that is the role of iconography – to study and examine the various aspects of artwork to try and understand what the artist intended when he used the various individuals, settings, and items that he chose to incorporate in his work.

What Are the Types of Iconography in Art?

When it comes to iconography art history, there are two types of art – religious and secular art. Secular means that it has nothing to do with any religious context, yet the objects displayed still have some significant meaning, such as mythological or historical paintings. Then there is also religious iconographic art, which is itself split into various categories, such as Western and Eastern religious artworks, which all have their own unique symbolic systems.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “What Is Iconography? – In-Depth Definition, Examples and History.” Art in Context. January 16, 2023. URL: https://artincontext.org/what-is-iconography/

Meyer, I. (2023, 16 January). What Is Iconography? – In-Depth Definition, Examples and History. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/what-is-iconography/

Meyer, Isabella. “What Is Iconography? – In-Depth Definition, Examples and History.” Art in Context, January 16, 2023. https://artincontext.org/what-is-iconography/.