Famous Sculptures – History’s 18 Most Famous Sculptures

From the earliest historical sculptures excavated from archaeological sites to the most famous sculptures created by Renaissance artists, one can still appreciate the development of such fine sculptural techniques and visual styles. The most famous art statues were created with the intention to be viewed in the round and to encourage the viewer to engage with them. Throughout the centuries, many famous sculptors have been exploring the dynamic relationships between the observer, location, and sculpture while leveraging a multitude of techniques to enhance our experience of age-old narratives and characters. In this article, we will explore 18 of the most famous sculptures in art history that have remained iconic since their creation. Read on for more about the world’s most famous sculptures!

An Introduction to Sculpture

Sculptural art such as Michelangelo’s famous works may be the most well-known by the public, but historical sculptures in art extend far back into human history. For thousands of years, sculpture has been at the forefront of art itself, making it an incredibly popular medium. The expertise required to make a sculpture is remarkable considering that master sculptors of the past took years to complete a single sculpture. Historical sculptures have a considerably higher probability of survival than paintings or drawings since they were mostly constructed from stone or bronze. As such, we still have remnants of ancient sculptures in art history that date back to almost 40,000 years ago!

The world’s most famous sculptures have become an essential component of our knowledge of ancient societies and important historical figures.

The Most Famous Sculptures in Art History

Famous sculptors throughout history have transformed stone, metal, timber, as well as other materials into extraordinary sculpture by manipulating objects and their forms. Since the dawn of civilization, art and sculpture have been a vital means of comprehending and communicating aspects of society and culture. Whether it is in the form of famous art statues or metaphorical depictions of moral concepts, one can be sure to encounter a new experience. While reviewing all the historically significant sculptures of the world may be daunting and lengthy, we have compiled a selection of some of the most famous sculpture and statues that will help you learn more about the origins of these iconic structures.

Venus of Willendorf (c. 25,000 BCE) by Unknown

| Artist | Unknown (c. 25,000 BCE) |

| Date | c. 25,000 BCE |

| Medium | Limestone and red ochre |

| Dimensions (cm) | 11.1 (h) |

| Where It Is Housed | Naturhistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria |

This little figurine was unearthed in the early 20th century and assigned the title of Venus of Willendorf, which was based on its function as a sculpture for fertility. While this theory has been supported for many years, archaeologists, historians, and other specialists in the area are still unsure about its true function or provenance. These Venus figurines were found as a collective group of statues from the Upper Paleolithic era in Willendorf, Austria, and was created around 25,000 BCE, making it one of the earliest known pieces of art.

The figurines were chiseled from limestone and ornately decorated with red ochre to represent a nude woman or the goddess of fertility, Venus.

Despite the lack of a distinct face, the cap of the statue’s head was incised with a recurring design that resembled a braided hairstyle or headpiece. More intriguing than the sculptor’s choice to keep the figure anonymous was the manner they chose to portray Venus’ body. The sculptor intentionally distorted the figures’ dimensions using exaggerated features such as the enlarged hips and breasts, alluding to procreation.

Many academics have determined that the sculpture was supposed to represent a fecundity sculpture or “Venus figurine” due to the subject’s large bosom, curved stomach, and curvaceous thighs.

While the sculptures’ beginnings are unknown, most scholars assume they possessed a ritual function and presumably glorified notions associated with fertility, womanhood, deities, and sensuality. Around 144 reproductive sculptures have been discovered throughout Asia and Europe to date. While not all of these figurines have the sensuous characteristics of the Venus of Willendorf, the majority do. This was a result of prehistoric notions of a woman’s capacity to procreate, which was linked to her physical appearance. Among the most famous statues from the Paleolithic era include artifacts such as the Venus of Hohle Fels and the Löwenmensch Figurine (c. 35-40 kya), both of which were found to be the oldest and most famous statues.

Bust of Nefertiti (1345 BCE) by Thutmose

| Artist | Thutmose (c. 14th century BCE) |

| Date | c. 1345 BCE |

| Medium | Limestone and stucco |

| Dimensions (cm) | 48 (h) |

| Where It Is Housed | Neues Museum, Berlin, Germany |

The Bust of Nefertiti was most likely carved around 1340 BCE, which was around the same time as the reign of King Akhenaten. It weighs 44 pounds and is life-sized, having been cut from a single slab of limestone. In ancient Egyptian civilization, the notion of royal portraiture was nothing out of the ordinary. They are abundant throughout Egypt’s palaces.

The representation of the monarch is what distinguishes this image. While we’re used to seeing blocky, substantial colossal images of an Egyptian pharaoh, Nefertiti’s bust is rather distinct.

The head was not only chiseled with curved cheeks, a powerful chin, and a pointed nose, but its stone core was also coated with gypsum plaster before being painted. The resulting effect was a realistic portrait of Queen Nefertiti. The Bust of Nefertiti was adorned with a golden-brown complexion, crimson lips, colorful jewels, and a royal headdress.

The eyes were also crystal-set with one eye fashioned from black wax. Scholars found that the other iris was never completed, making the bust an unfinished project. So, who made this work of art? The greatest hint comes from the location of the figure’s discovery. As previously assumed, the sculpture was discovered in a studio and not a mausoleum or home.

The “Bust of Nefertiti” was discovered in the studio of the authorized royal sculptor, Thutmose, who was also Akhenaten’s favorite craftsman.

The fact that the bust was discovered at Thutmose’s workshop in Amarna indicates that it was most likely a model for a larger sculpture. It is believed that Thutmose created the bust as a guide so that he might have the queen’s visage with him when sculpting additional royal, and potentially colossal, portraits.

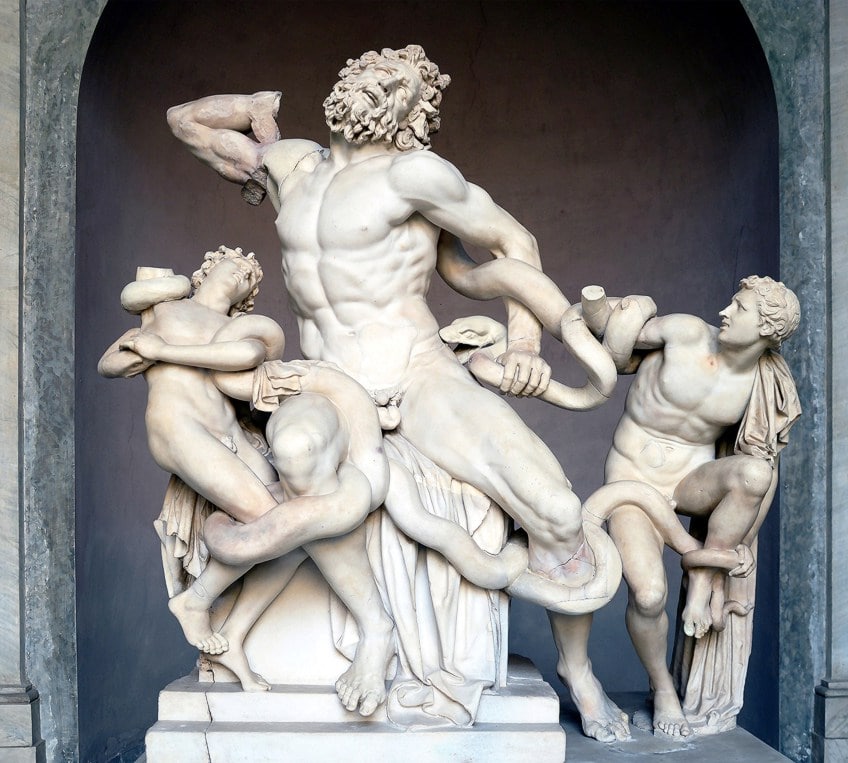

Laocoön and His Sons (c. 2nd Century BCE) by Agesander, Polydorus, and Athenodorus

| Artist | Agesander, Polydorus, and Athenodorus of Rhodes (c. 2nd century BCE) |

| Date | (c. 2nd century BCE) |

| Medium | Marble |

| Dimensions (cm) | 208 × 163 × 112 |

| Where It Is Housed | Vatican Museums, Vatican City |

Laocoön and His Sons is a famous sculpture attributed to three sculptors of the 2nd century: Agesander, Polydorus, and Athenodorus, who created the work as an embellishment for the home of the Roman emperor Titus. The sculpture is a demonstration of the ultimate expression of human agony and differs significantly from the expressions of agony seen in many religious artwork. The nearly life-sized sculpture depicts the a Trojan priest called Laocoön with his sons Antiphantes and Thymbraeus, who are facing an attack by a horde of sea serpents. The sculpture was also highly praised by the renowned ancient philosopher Gaius Plinius Secundus, also known as Pliny the Elder, in his publication, Natural History (c. 77 CE).

Natural History describes the artwork as “carved from a single slab, both the principal image, as well as the youngsters and the snakes, with their amazing coils,” and calls it “a creation that may be considered superior to any other sculpture in bronze”.

What is unclear from Pliny’s statements and continues to be a source of debate to this moment is whether the statue he witnessed was an authentic piece or a replica, as some claim, of a “long-lost classic”.

What we do understand is that Pliny’s glowing praise of the artwork remained true even upon its rediscovery in February of 1506. When Pope Julius II learned that a trove of historical sculptures had been discovered, he ordered a team of specialists to supervise its extraction.

A youthful sculptor named Michelangelo, who had just created a bold and much-publicized monument of David (1501-1504) in Florence, as well as Lorenzo de Medici’s favorite architect, Giuliano da Sangallo, were there for the painstaking excavation. Francesco, Giuliano’s young son, was also present at the dig and would go on to become a well-known artist in his own right.

“Laocoön and His Sons” had an enduring influence on Michelangelo’s creativity and informed the sculptural approaches in many of his famous works.

Nike of Samothrace (c. 190 BCE) by Unknown

| Artist | Unknown (c. 190 BCE) |

| Date | c. 190 BCE |

| Medium | Parian marble |

| Dimensions (cm) | 557 (h) |

| Where It Is Housed | Louvre Museum, Paris, France |

The Nike of Samothrace is by far one of the most renowned masterpieces of Hellenistic art. The embodiment of a winged triumph is represented by the pale Parian marble sculpture. The statue’s face and limbs also appear missing, however, despite the missing parts, the sculpture stands at a towering 5.57 meters tall. The masterful representation of the flowing drapery on her tunic gives one the sense that Nike is about to plummet from the sky in the midst of a storm. Her tunic’s cloth is pushed against her torso and appears drenched from the humidity of the sea.

The deity sports a corset across her hips and under her bosom, over which wrinkles drape spectacularly. In the 4th century BCE, this method of doubling a woman’s garment was common.

The Winged Victory of Samothrace sports a cloak over her tunic, which conceals her right leg and is pushed against her torso by the fictitious power of the ocean breeze. The deity’s feathery wings are also stretched as if she was suspended in motion. The Winged Victory of Samothrace was designed to be appreciated in a three-quarter perspective from its left side. This is especially noticeable on the right side of the torso, which, like the rear-side of the artwork, was sculpted in considerably less detail.

In comparison to the vibrant arrangement and exquisite detailing on the left side of the sculpture, the layout on the right side was considerably minimal. The grayish marble foundation also shows that the sculpture was designed not just as a homage to Nike, but as a reminder of the victory from a maritime battle.

The artwork stands at over five meters tall when combined with the foundation and the platform on which it sits.

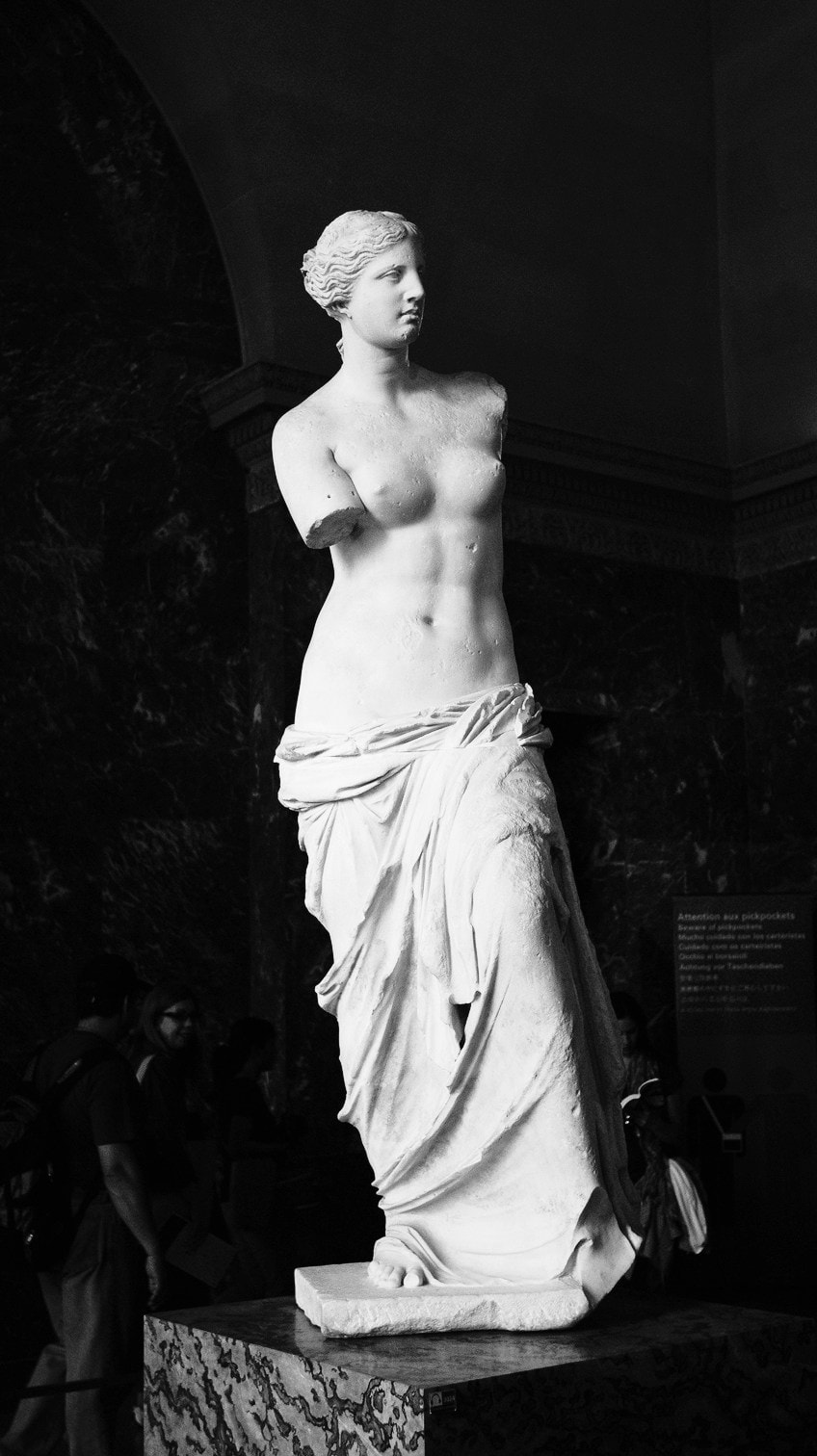

Venus de Milo (c. 130 BCE) by Alexandros of Antioch

| Artist | Alexandros of Antioch (c. 2nd century BCE) |

| Date | c. 130 BCE |

| Medium | Parian marble |

| Dimensions (cm) | 207.2 (h) |

| Where It Is Housed | Louvre Museum, Paris, France |

The famous Venus de Milo was discovered on the Greek island of Milos and has since become one of the most iconic Greek sculptures of all time. The statue represents the Greek goddess of love Aphrodite and is recognized for its missing arms, which was common for many discoveries of sculptures from antiquity. The sculpture was discovered by a young man in a field, who found Venus concealed in a wall amid the ancient city’s remains. The marble sculpture was divided into two parts: the upper body and the draped limbs. Several more sculptural parts, including a second left arm grasping an apple and an engraved plinth were unearthed nearby.

“Venus de Milo” is a renowned statue of the Greek goddess of love, Aphrodite, who is recognized in Roman culture as “Venus”.

Also recognized as the Aphrodite of Milos, the statue was sculpted from two slabs of Parian marble and was once composed of various individual elements that were carved long before they were attached with vertical pins. Unfortunately, the statue’s original pedestal and missing arms have remained elusive to the public since its arrival in Paris in 1820.

This was partly owing to classification problems because when the sculpture was first rebuilt, the adjoining parts of the left hand and arm were not thought to correspond to it due to their overall ‘rougher’ look. Experts concluded that these additional sections were part of the original sculpture because it was a normal procedure at the time to spend less work on less visible portions of a statue.

“Venus de Milo” was sculpted in fine Parian marble and has become an iconic figure in Greek art history for her missing arms, ear lobes, and left leg.

Specialists in statue restoration estimate that Venus de Milo‘s individually sculpted right arm rested across her body, with her right hand resting on an elevated left knee. At the same time, it is speculated that her left arm once carried an apple at an eye-level height. It has been a subject of debate as to whether the deity was staring at the fruit she was carrying or into the distance.

David (c. 1440) by Donatello

| Artist | Donatello (1386 – 1466) |

| Date | c. 1440 |

| Medium | Bronze |

| Dimensions (cm) | 158 (h) |

| Where It Is Housed | Bargello National Museum, Florence, Italy |

The Palazzo Medici was a center of commerce and social interaction with a central courtyard that was accessible from the street by the main gate. One of the most inventive statues of the early Renaissance was Donatello’s bronze David, which was installed on a pedestal and viewed when the city’s main entrance opened to visitors. David portrayed new techniques in early Renaissance sculpture since it is the oldest known standing nude statue since ancient times. Moreover, it was made from bronze, which was an expensive medium that was not commonly utilized for large-scale standalone sculptures throughout the Middle Ages.

The topic of this statue was David, the heir to the throne and protagonist of the Holy scriptures, who killed the giant Goliath as a young man and freed his nation (the Hebrews) from the oppression of the Philistine people.

David’s adolescence is obvious in Donatello’s statue and was depicted through the character’s nudity and gentle physique. His character was juxtaposed with Goliath’s thick facial hair and wisdom, whose headless body lies at David’s feet. The rock he clutches in his left hand emphasizes David’s weakness, a reflection that, although wielding a sword, he was able to take down the gigantic antagonist with a single slingshot.

The moral is clear in the character and depiction of David, as a character that prevailed not by physical might but through God’s favor.

While the scriptural story mentioned that David opted not to fight Goliath in the armor handed to him by his father, it never mentioned that he was stripped naked. David is dressed in all previous representations of his character, along with an older marble figure sculpted by Donatello. The decision to represent David entirely naked, save for a shepherd’s cap ornamented with triumphal wreaths and ornate footwear, was unusual, and perhaps hinted at Donatello’s homosexuality. Today, Donatello’s David is housed at the Bargello Museum in Florence, as well as a famous bas-relief by Donatello called St. George and the Dragon (c. 1416-1417) in the Hall of Donatello.

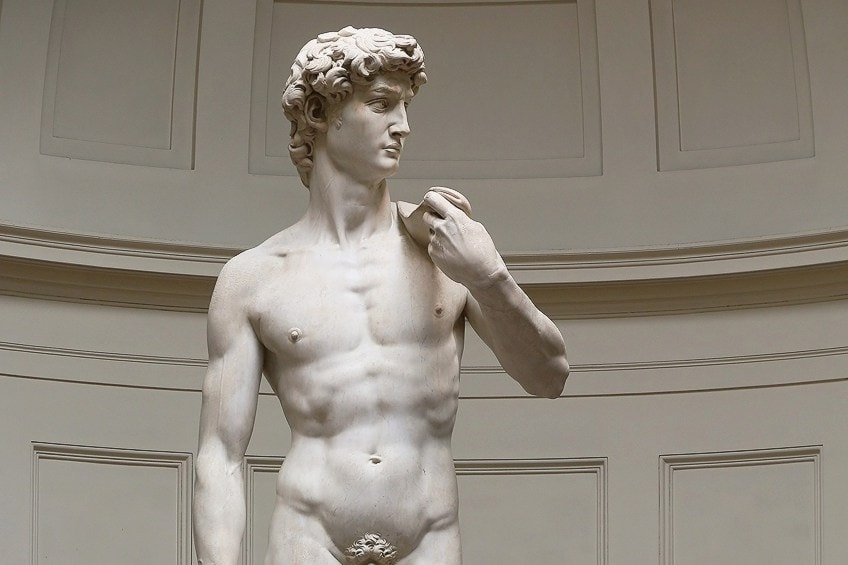

David (1504) by Michelangelo

| Artist | Michelangelo (1475 – 1564) |

| Date | 1504 |

| Medium | Marble |

| Dimensions (cm) | 517 × 199 |

| Where It Is Housed | Galleria dell’Accademia, Florence, Italy |

David was initially ordered for the Cathedral of Florence as part of a series of enormous sculptures to be placed in the recesses of the cathedral’s tribunes, nearly 80 meters above ground. The representatives of the cathedral’s board commissioned Michelangelo to complete a task initiated by Agostino di Duccio in 1464. Both artists eventually refused a massive piece of marble owing to the existence of too many faults, which may have jeopardized the structure of such a massive monument.

As a result, this magnificent piece of marble went unnoticed for 25 years, resting within the grounds of the vestry board.

In 1501, when Michelangelo was just 26 years of age, he was already renowned as one of the most recognized and well-paid artists of his day. He eagerly embraced the task of sculpting a monumental David statue and worked tirelessly for almost two years to produce one of his most magnificent works from shining white marble. The vestry board had chosen a theological theme for the monument but no one expected such a radical portrayal of the legendary figure.

Historically, David was portrayed as a victorious character, standing over Goliath’s body. Florentine painters created their own rendition of David poised over the dismembered skull of Goliath. Instead of following tradition, Michelangelo depicted David before the conflict began and captured David at the peak of a tense moment.

In the statue, David appears to maintain a comfortable, yet attentive posture resting on a traditional position known as contrapposto. The model stands with one leg fully supported and the other limb extended, forcing the hips to rest at opposite angles, and providing the statue with a small s-shaped curve. The slingshot he carries across his shoulders is initially undetectable, suggesting that David’s triumph was achieved via his cunning intelligence rather than brute force. Today, David can be viewed at the Accademia Gallery in Florence, Italy, which is the statue’s second home since its installation in 1873.

“David” exudes tremendous self-assurance and focus, which were two traits associated with the “thinking person,” often regarded as the pinnacle of excellence during the Renaissance.

The Rape of Proserpina (1621 – 1622) by Gian Lorenzo Bernini

| Artist | Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598 – 1680) |

| Date | 1621 – 1622 |

| Medium | Carrara marble |

| Dimensions (cm) | 225 (h) |

| Where It Is Housed | Borghese Gallery and Museum, Rome, Italy |

This famous marble sculpture by Gian Lorenzo Bernini was created in the early 17th century and exemplifies the sculptor’s strengths in his knowledge of physiology, movement, and emotion. Whereas the craftsman’s skills continue to be lauded today, the artwork’s distasteful source material has placed a problematic shadow over it, despite being a classic highlight of the Baroque period.

In 1622, Bernini completed “The Rape of Proserpina” at the age of 23, which earned him significant recognition in the eyes of his contemporaries, who were much older.

Bernini established a reputation for himself as a distinguished sculptor in the early 1620s with four masterpieces. The sculpture was crafted from a fine marble called Carrara marble, which was sourced from Tuscany and traditionally used by ancient Roman architects, including mannerist and Renaissance artists.

The delicacy of this high quality marble lent itself to Bernini’s art since he took great pleasure in giving marble the illusion of skin. This fascination in changing stone into skin was most visible in The Rape of Proserpina, a work designed to depict a spectacular capture (the phrase “rape” alludes to the deed of abduction). Like many of Bernini’s earliest works, it was ordered by Cardinal Scipione Borghese, an enthusiastic artwork connoisseur and loyal supporter of Bernini.

Following the High Renaissance, there was a resurgence of enthusiasm in resurrecting a Classical style of painting, including topics influenced by ancient Roman and Greek mythology.

Ecstasy of Saint Teresa (1647 – 1652) by Gian Lorenzo Bernini

| Artist | Gian Lorenzo Bernini |

| Date | 1647 – 1652 |

| Medium | White marble |

| Dimensions (cm) | Life-sized |

| Where It Is Housed | Church of Santa Maria della Vittoria, Rome, Italy |

Ecstasy of Saint Teresa is one of the most famous sculptures by Gian Lorenzo Bernini, who created the masterpiece between 1647 and 1652. Bernini was inspired by the epic tale of a 16th-century Spanish nun named Teresa of Ávila, who described her love for God and her experience of “religious ecstasy” through her visions. Teresa of Ávila described a vision, which involved her encounter with an angel, who pierced her heart several times, such that she experienced both pain and pleasure.

Teresa’s experience described a spiritual pain and her soul’s delight at the intensity of the experience and her love for God.

This inspired Bernini to sculpt the moment of intense spiritual awareness in a Baroque fashion. The sculpture was commissioned by the Cornaro family, who required a piece for the Cornaro chapel, located at the Church of Santa Maria della Vittoria in Rome, Italy. The placement of the sculpture was also key since the panels on the sides of the sculpture feature scenes of figures who appear to discuss the subject of Teresa and the angel in a theater box setting. The figures portrayed in the walls surrounding the sculpture include Bernini’s patron, Federico Cornaro, and many posthumous portraits of other members of the Cornaro family.

Perseus with the Head of Medusa (1804 – 1806) by Antonio Canova

| Artist | Antonio Canova (1757 – 1822) |

| Date | 1804 – 1806 |

| Medium | Marble |

| Dimensions (cm) | 242.6 x 191.8 x 102.9 |

| Where It Is Housed | The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, United States |

Perseus with the Head of Medusa is a renowned sculpture by famous Italian sculptor Antonio Canova, who was widely regarded as one of the masters of the early 19th century. Perseus with the Head of Medusa is a dynamic sculpture that reflects Canova’s interest in antiquity subjects and was based on the Apollo Belvedere. Perseus with the Head of Medusa shows the figure of Perseus standing in an Apollo pose with his gaze focused intently on the decapitated head of the Greek Gorgon Medusa, which was inspired by the Rondanini Medusa mask in Munich. Perseus with the Head of Medusa was acquired by Pope Pius VII, who installed the sculpture in the former location of the Apollo Belvedere (c. 15th century) sculpture.

Scholars have debated the ownership of the original sculpture, speculating among records that claim that the first sculpture was flawed and re-gifted to the Countess Tarnowska and thereafter, a second copy was produced for the Pope.

Canova often advised to his viewers and fans to appreciate his works in candle-lit environments to truly experience the artwork. Another famous sculpture by Canova is Psyche Revived by Cupid’s Kiss (1793), which was commissioned by Colonel John Campbell a few years earlier.

Statue of Liberty (1886) by Auguste Bartholdi

| Artist | Auguste Bartholdi (1834 – 1904) |

| Date | 1886 |

| Medium | Copper sheets |

| Dimensions (cm) | 9300 (h) |

| Where It Is Housed | Liberty Island, New York City, United States |

The Statue of Liberty was a collaborative sculptural project involving the governments of France and the United States as a celebration of the two countries’ long-standing relationship. The monument was constructed by the French artist Frederic-Auguste Bartholdi from strips of pounded copper. The Statue of Liberty was then transported in parts to the United States and built on a tiny island in Upper New York Bay, and inaugurated in 1886 by President Grover Cleveland.

The Statue of Liberty stood strong as waves of foreigners landed in New York via neighboring Ellis Island over the decades. In 1986, the statue received a major refurbishment to commemorate the centenary of its inauguration. As the American Civil War came to an end in 1865, the French historian Edouard de Laboulaye suggested that France make a monument to donate to the United States in honor of that country’s accomplishment in creating a sustainable government.

The project was given to the artist Frederic Auguste Bartholdi, who was known for creating monumental works. The objective of the project was to complete the monument in time for the centenary of the Declaration of Independence in 1876.

The collaboration saw the French artist in charge of the monument and its construction, while the United States’ architects would construct the podium, as an emblem of their citizens’ goodwill. Construction on the statue did not commence until 1875, due to the necessity to gather funding for the memorial.

Bartholdi used enormous copper panels to build the monument’s “skin,” which was reported to be patterned by his mother’s visage using a method known as “repousse”.

Bartholdi enlisted the help of Alexandre-Gustave Eiffel, the creator of Paris’ Eiffel Tower, to develop the framework over which the shell would be built. Eiffel collaborated with Eugène-Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc to create a framework of iron pillar and steel that allowed the copper covering to move freely since the statue would be exposed to severe gusts of wind.

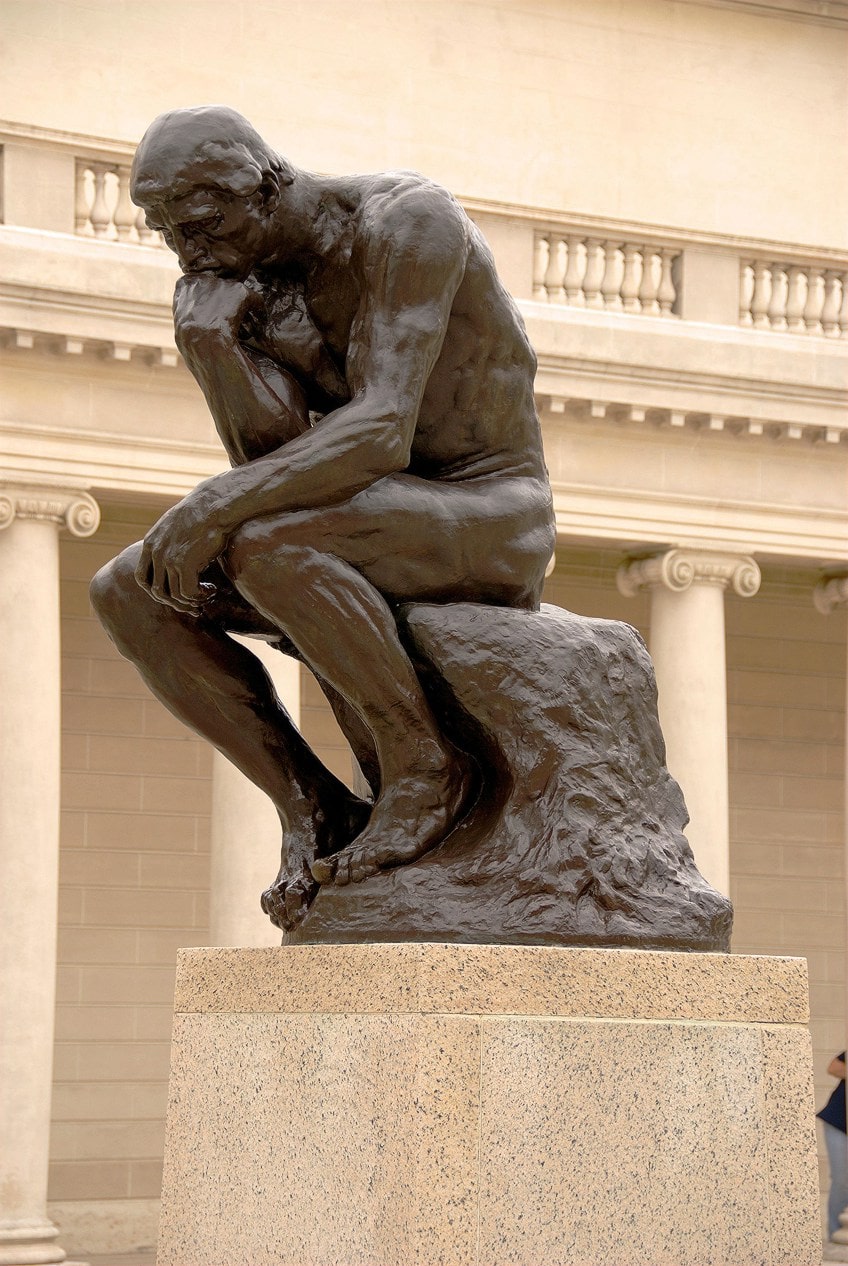

The Thinker (1880) by Auguste Rodin

| Artist | François Auguste René Rodin (1840 – 1917) |

| Date | 1880 |

| Medium | Bronze |

| Dimensions (cm) | 185 (h) |

| Where It Is Housed | Kunsthaus Zürich, Zürich, Switzerland |

The Thinker was part of a huge contract undertaken in 1880 for The Gates of Hell, an entryway surrounding. The Thinker is located in the middle of the arrangement, above the entryway, and is slightly larger than the majority of the other sculptures. Some scholars believe it was initially meant to portray Dante Alighieri contemplating his famous poem at the gates of hell.

Others disagreed with the interpretation of the sculpture, citing that the body was nude, although Dante was completely dressed throughout the passage, and that the sculpture’s body does not correlate to Dante’s effete form. Rodin intended a noble form, inspired by Michelangelo’s style, to convey intelligence as well as beauty, hence the artwork was sculpted as a nude. The figure is depicted leaning on his elbow, which is planted on his left leg, and his chin resting on his fist.

The monument’s attitude is one of intense contemplation and concentration, which was frequently used as a pose to depict philosophical thought and character.

Rodin created the statue as a component of his project The Gates of Hell, which was contracted in 1880, but the first of the famous massive bronze molds was completed in 1904, and is currently on display at the Musée Rodin in Paris.

The sculpture was cast in several variants and can be seen all over the world, however, the chronology of the transition from models to molds remains unclear.

There are around 28 monumental-sized bronze castings in galleries and public sites around the globe. There are other copies in various study-sized dimensions, as well as plaster replicas (typically painted bronze) in both massive and study proportions. Some later castings were created after his death and are not considered to be part of the initial project.

Unique Forms of Continuity in Space (1913) by Umberto Boccioni

| Artist | Umberto Boccioni (1882 – 1916) |

| Date | 1913 |

| Medium | Bronze |

| Dimensions (cm) | 121.3 × 88.9 × 40 |

| Where It Is Housed | Museum of Modern Art, New York City, United States |

Unique Forms of Continuity in Space incorporates velocity and power dynamics into the depiction of a striding individual. It does not portray a specific individual at a precise point in time but rather combines the act of moving into a single entity. This was a precise state for Boccioni, a significant character in the Italian Futurist movement, who was portrayed as a body in perpetual movement, submerged in time, and connected with the forces operating on it.

Boccioni claimed he had little interest in traditional or Renaissance sculptures. “Anyone now who believes Italy to be the nation of art is a sexual deviant who thinks of a graveyard as a charming little grotto”, he said in Futurist Painting Sculpture (1914), a manifesto-style book.

Boccioni asserted that art should “have a tight historical relationship with the period in which it occurs”; early 20th-century sculptures, he believed, would represent the pace and intensity of Italy’s rapid urbanization.

Boccioni and the other Futurists saw the impending global war as a logical evolution, one that would obliterate the vestiges of history and bring people and technology closer together. “Let us tear the form wide and allow anything that might encircle it, to assimilate inside itself”, Boccioni remarked. He defied sculptural convention by opening up the shape of this moving creature, who forges onward as though chased by haste. While the triumphal attitude and armless body are reminiscent of sculptures from previous periods of art history, the gleaming metal refers to Contemporary technology.

Boccioni was a pivotal character in the Futurist movement, whose followers violently rejected the past in favor of designing shapes that reflected the vitality and inventiveness of the machine era.

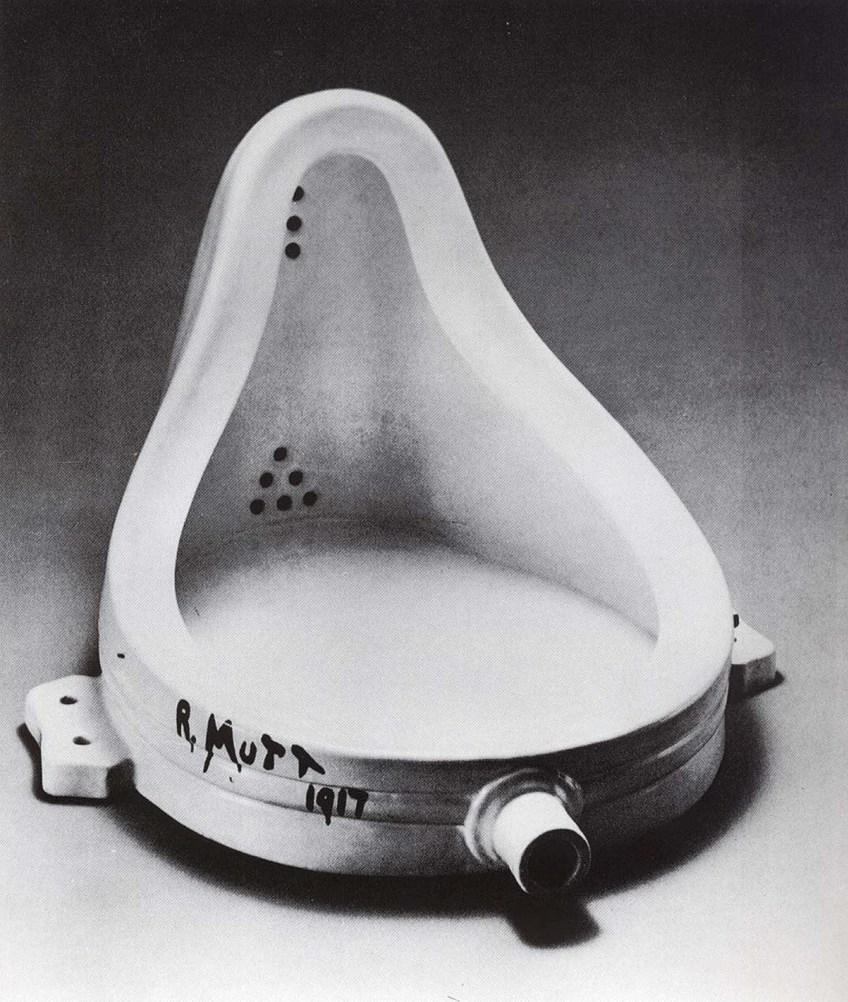

Fountain (1917) by Marcel Duchamp

| Artist | Marcel Duchamp (1887 – 1968) |

| Date | 1917 |

| Medium | Porcelain |

| Dimensions (cm) | 61 x 36 x 48 |

| Where It Is Housed | Tate Modern, London, United Kingdom |

Fountain is a 1917 found sculpture by Marcel Duchamp that consists of a ceramic urinal signed “R. Mutt”. The urinal was entered for an exhibition held by the Society of Independent Artists at the Grand Central Palace in New York in 1917.

Duchamp described his pre-made sculptures as “common things elevated to the grandeur of a piece of artwork by the creator’s act of selection”.

The urinal’s position was changed from its regular placement in Duchamp’s display. Fountain was not refused by the panel because the organization’s regulations indicated that all artworks submitted by creators who submitted the money would be admitted, but the sculpture was never displayed. Fountain was photographed in Alfred Stieglitz’s workshop after his departure and the image was printed in the Dada publication The Blind Man. Since then, the original work has been lost, however, the piece is considered an important benchmark of 20-century art by many scholars and Avant-Garde thinkers.

In the 1950s and 1960s, 16 reproductions were requested from Duchamp, which he created according to established agreements. Some speculate that the original piece was created by an unnamed woman who sent it to Duchamp as an acquaintance, but art critics speculate that Duchamp was completely responsible for Fountain‘s representation.

Duchamp’s “Fountain” was possibly the most well-known sculptures from the readymades in this collection because the figurative significance of the toilet pushes the intellectual issue proposed by the notion of “readymades” to its highest emotional degree.

Likewise, philosopher Stephen Hicks suggested that Duchamp, who was well-versed in European art history, was clearly making a controversial statement with Fountain. “Duchamp, the artist, is a mediocre creator…he went shopping at a plumbers department. The sculpture is not a one-of-a-kind item; it was mass-produced in a facility. Art is not an exhilarating or uplifting experience; at best, it is perplexing and generally leaves one with a bad taste”.

Statue of Abraham Lincoln (1920) by Daniel Chester French

| Artist | Daniel Chester French (1850 – 1931) |

| Date | 1920 |

| Medium | Georgia marble |

| Dimensions (cm) | 580 (h) |

| Where It Is Housed | Lincoln Memorial, Washington, D.C., United States |

This world-famous Statue of Abraham Lincoln is perhaps the most recognizable sculpture in art history that was created for the Lincoln Memorial at the National Mall. The monumental statue of the United States’ 16th President was created by Daniel Chester French between 1914 and 1920, and unveiled to the public in 1922. The sculpture was constructed from Georgia marble and weighs approximately 170 tonnes.

What makes the “Statue of Abraham Lincoln” so profound is its patriotic atmosphere displayed in the solemn expression on Abraham Lincoln’s face.

Daniel Chester French was selected by the Lincoln Memorial committee to create a sculpture for inclusion in the design by Henry Bacon, whom French had already encountered in many collaborations for around 25 years. Today, the Statue of Abraham Lincoln remains an iconic part of Washington D. C. and the United States’ American Renaissance style.

Bird Girl (1936) by Sylvia Shaw Judson

| Artist | Sylvia Shaw Judson (1897 – 1978) |

| Date | 1936 |

| Medium | Clay and bronze (cast) |

| Dimensions (cm) | 130 (h) |

| Where It Is Housed | The Jepson Center, Savannah, Georgia, United States |

When Sylvia Shaw Judson’s sculpture of Bird Girl was featured on the book jacket of Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil (1994), countless reproductions of the young lady clutching the bowls began across the art market. Judson’s daughter, who owns all of her family’s sculpture copyrights, was enraged and began pursuing legal action to eliminate the heinous duplicates on the market. Brian Caldwell, the creator of Potina, approached Judson’s daughter in the spring of 1998 and proposed releasing an estate-approved replica of the Bird Girl monument. Caldwell recalls telling her, “Someone’s going to continue producing her. I want to treat her properly”.

After much deliberation, Judson’s estate consented to provide Potina with an exclusive license to create and sell reproductions of the monument.

By the end of the year, she had been on the front of three leading catalogs and was distributed in garden centers and souvenir shops around the country. Sylvia Shaw Judson, the Bird Girl‘s designer, was born in Lake Forest, Illinois, and studied at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and Paris. Her style has been praised by reviewers as modest, clear, peaceful, childlike, quiet, and lovely. Judson was most famous for her adorable renditions of animals and children, but she also created some well-known commissioned pieces with theological themes that represent her Quaker ancestry.

Today, Judson’s statues and fountains can be seen in gardens and city parks throughout the United States.

Maman (1999) by Louise Bourgeois

| Artist | Louise Bourgeois (1911 – 2010) |

| Date | 1999 |

| Medium | Bronze, marble, and stainless steel |

| Dimensions (cm) | 927 x 891 x 1024 |

| Where It Is Housed | Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, Bilbao, Spain |

Louise Bourgeois created Maman in marble, bronze, and stainless steel to resemble a spider and is one of the world’s biggest sculptures to date. The large spider sculpture stands at more than 30 feet tall and 33 feet wide with a sac containing 32 marble eggs, and legs constructed from ribbed metal. The title is a play on the French term meaning “Mother” and was produced in 1999 as a portion of Bourgeois’ debut project, The Unilever Series (2000), for exhibition at London’s Tate Modern Turbine Hall. This steel sculpture was followed by a series of six smaller bronze casts.

The sculpture elaborates on the terrifying image of the spider, which Bourgeois initially explored in a small ink and charcoal painting in 1947, and later continued with her 1996 piece “Spider”.

Maman references Bourgeois’ mother and her strength through the spider and its ability to spin, weave, nurture, and protect its young. Her mother, Josephine, worked at her father’s textile repair studio in Paris, repairing tapestry. Bourgeois’ mother died of an undisclosed disease when she was only 21 years old. Louise plunged herself into the Bièvre River a few days after her mother died, in front of her father, who did not appear to take his daughter’s sadness seriously.

“The Spider is a love letter to my mum. She was my closest companion. My mother was a spinner, much like a spider. My household was in the tapestry repair industry, and my mother was in control of the factory. My mom, like spiders, was extremely intelligent. Spiders are pleasant insects that prey on mosquitoes. Mosquitoes are known to carry illnesses and are so unwelcome. Spiders, like my mother, are useful and watchful”, she wrote.

Cloud Gate (2004) by Anish Kapoor

| Artist | Sir Anish Mikhail Kapoor (1954 – Present) |

| Date | 2004 |

| Medium | Stainless steel |

| Dimensions (cm) | 1000 x 2000 x 1300 |

| Where It Is Housed | Millennium Park, Chicago, United States |

The liquid shape of mercury influenced Anish Kapoor’s creation Cloud Gate, which reflects and distorts the image of Chicago’s cityscape. Visitors may walk around it and beneath Cloud Gate‘s 3.7-meter-high arch to gain a full experience of the artwork. The navel is a concave cavity on the bottom that distorts and amplifies reflection. Many of Kapoor’s creative ideas are included in the sculpture, which is popular with visitors as an opportunity to take a picture due to its distinctive reflective quality. Cloud Gate was part of a contest, which Kapoor won, however, many questions and concerns around the sculpture’s maintenance and manufacturing surfaced.

Several specialists were engaged, with some claiming that the concept could not be accomplished. Although a workable building process was discovered, the sculpture’s development slipped behind the appointed time schedule. It was displayed in a partial version at the official opening ceremony of Millennium Park in 2004, before being hidden again until it was finalized on May 15, 2006. It was later agreed upon that the elements itself contributed to the upkeep of the sculpture, including snow that could be brushed away by the many people who touch it, allowing them to snap creative selfies beneath its “navel”. Since its installation, Cloud Gate has grown in prominence both domestically and abroad.

Sculpture is one of the longest existing art forms due to the history of the materials used. Famous art statues continue to live on as remnants of bygone civilizations and remind us of the value that sculpture, and art, can bring to future generations.

Take a look at our famous statues webstory here!

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is the Most Famous Sculpture?

David by Michelangelo is regarded as the most famous sculpture of all time and was created between 1501 and 1504. The massive statue is considered to be the first statue of its size since the period of Classical antiquity.

What Is the Most Famous Public Sculpture?

The Statue of Liberty is considered to be the most famous public sculpture in the world that was created by Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi in 1876. The statue is located on Liberty Island in New York City and was designed as a gift from the French government to commemorate the relationship between France and the United States.

What Is the Oldest Sculpture in the World?

The Venus of Hohle Fels and the Löwenmensch Figurine are considered to be the oldest known sculptures in the world, dating back to 40,000 years ago. These figurines were discovered in Germany and are recognized as the oldest confirmed statuettes to date.

Who Is Regarded as the Best Sculptor in History?

The best sculptor and artist is considered to be Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni, who is simply known as Michelangelo. Michelangelo was an iconic “Renaissance Man”, who was accomplished in a variety of professions, including art, architecture, literature, and technology. Michelangelo was also recognized as “the Divine one” for his contribution to sculpture.

Who Were the Three Most Famous Sculptors in Art History?

Among the many talented master sculptors in art history were Michelangelo, Donatello, and Auguste Rodin. These three sculptors are considered to be the most influential sculptors of their relevant periods and shaped the traditional techniques and styles of sculpture from the Renaissance to the 19th century.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Famous Sculptures – History’s 18 Most Famous Sculptures.” Art in Context. November 6, 2021. URL: https://artincontext.org/famous-sculptures/

Meyer, I. (2021, 6 November). Famous Sculptures – History’s 18 Most Famous Sculptures. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/famous-sculptures/

Meyer, Isabella. “Famous Sculptures – History’s 18 Most Famous Sculptures.” Art in Context, November 6, 2021. https://artincontext.org/famous-sculptures/.

Thank you for compiling such a rich and insightful list of famous sculptures! I deeply appreciate the detailed descriptions and historical context provided for each piece. It’s fascinating to learn how these masterpieces have shaped and reflected the cultures of their time. Your article is a treasure trove for anyone passionate about art and history. Grateful for the effort and research that went into creating this!

Regards,

Larissa