Nike of Samothrace – History of the Winged Victory Sculpture

The Nike of Samothrace statue is named after the island on which it was found, situated to the north of the Aegean Sea. Now housed at the Louvre Museum, it is not known who made the Winged Victory of Samothrace, but it is believed to have been ordered to be built by Demetrius Poliocretes sometime between 295 and 290 BC. It is a Hellenistic-era Greek sculptural masterwork and depicts the goddess Nike.

The Nike of Samothrace Statue

| Date of Creation | c. 295 and 290 BC |

| Architect | Unknown |

| Dimensions | 2.74 m |

| Now Housed | Louvre Museum, Paris |

The Nike of Samothrace statue is also known as the Winged Victory of Samothrace. Although it was created in the 2nd century BC, it was not rediscovered until the 1860s. After that, it went through several periods of restorations. Let us start with the 19th century.

Discovery of the Nike of Samothrace Statue in the 19th Century

From the 6th of March until the 7th of May, 1863, Charles Champoiseau, operating in command of the Consulate of France, conducted the excavation of the remnants of the Sanctuary of the Great Gods on Samothrace Island. On the 13th of April 1863, he uncovered a bust and the body of a colossal female statue carved from white marble, together with several feathers and drapery pieces.

He recognized this as the goddess Victory or Nike, who was typically depicted as a winged lady in Greek mythology.

In the same location was a tangle of roughly 15 huge grey marble blocks, the shape or purpose of which he deduced was a burial monument. He made the decision to transport the sculpture and shards to the Louvre Museum while leaving the enormous slabs of grey marble on the location. After leaving Samothrace in early May 1863, the statue landed in Toulon at the close of August and in Paris on the 11th of May, 1864.

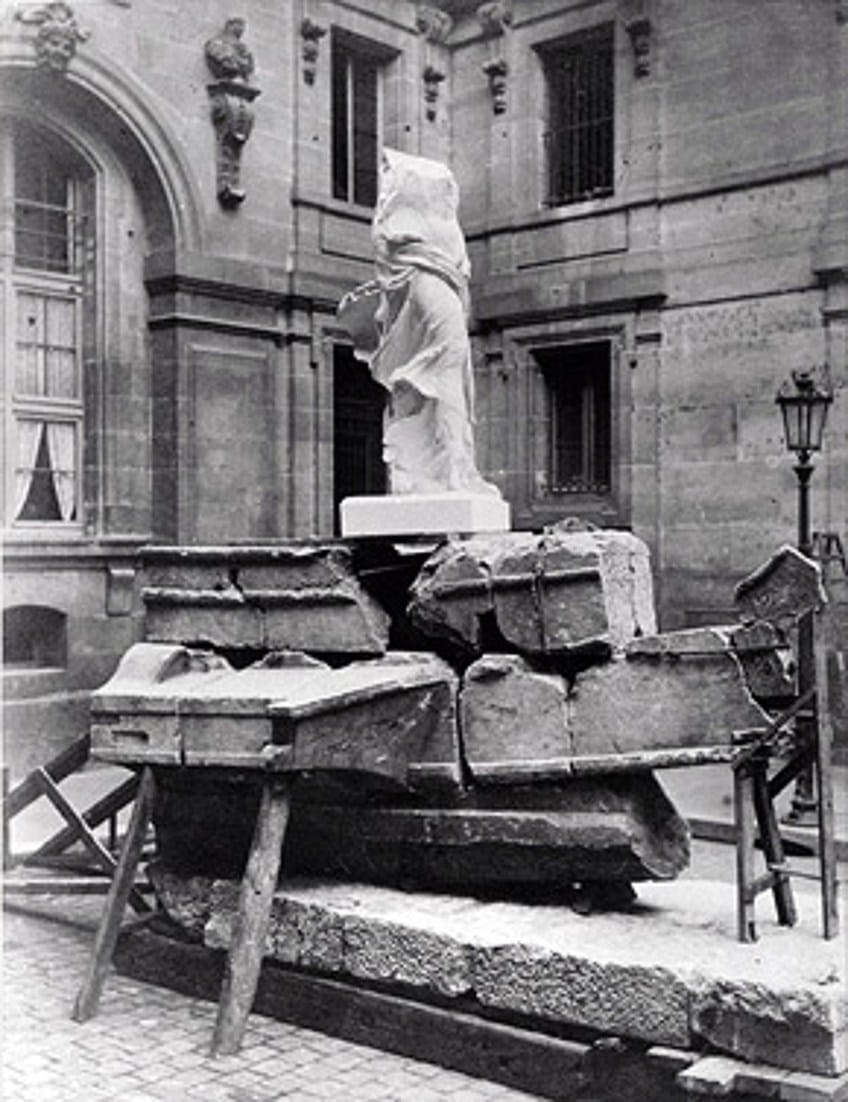

Adrien Prévost de Longpérier, formerly director of Antiquities at the Louvre, undertook the initial repair from 1864 until 1866. The main structure is constructed on a stone base and is substantially finished with fabric pieces, including Nike’s folds of himation that stretches behind the legs. The remaining components, which include the right side of the bust and a substantial portion of the left wing and are too enormous to be mounted on the sculpture, are kept in storage.

Given the outstanding craftsmanship of the sculpture, Longpérier opted to present the body alone, which was displayed among the Roman sculptures until 1880, initially in the Caryatid Room and then temporarily in the Tiber Room.

In 1875, Austrian scientists who had been unearthing the structures of the Samothrace shelter under the leadership of Alexander Conze since 1870 explored the spot where Champoiseau had discovered the Victory. Architect Alos Hauser sketched the grey marble stones left on-site and deduced that, when correctly constructed, they constituted the tapering bow of a vessel, and that, when set on a slab base, they functioned as the foundation for the sculpture.

Demetrios Poliorcetes’ tetradrachms, struck between 301 and 292 BCE, depicting a Victory on the head of a ship with wings spread, offer an excellent notion of this style of sculpture. For his role, O. Benndorf, an expert in ancient sculptures, is in charge of researching the statue’s body and the pieces preserved in storage at the Louvre and has reconstructed the sculpture to blast into a trumpet that she lifts with her right arm, as seen on the coin.

As a result, the two men were able to create a reconstruction of the whole Samothrace statue.

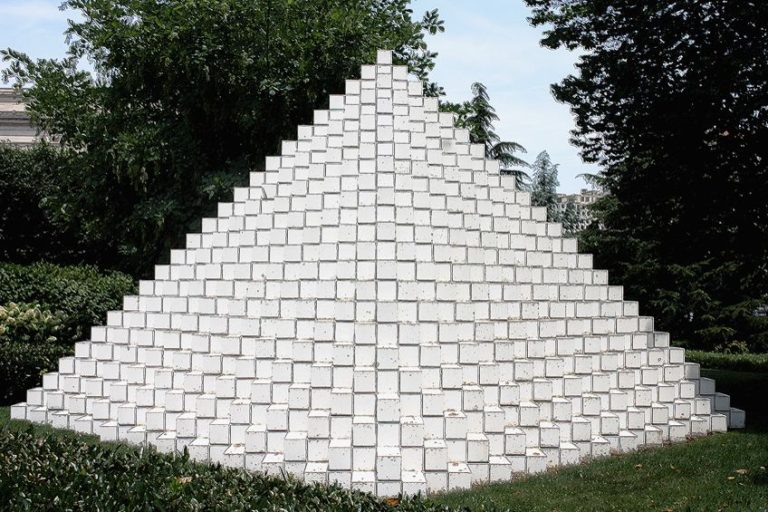

In response to this study, Champoiseau launched a second voyage to Samothrace from the 15th to the 29th of August, 1879, with the sole intention of transferring the stones of the foundation and the slab of the Victory base to the Louvre. He left the largest unsculpted slab of the base on the islands. Two months afterward, the blocks arrived at the Louvre Museum, where an installation test was conducted in a yard in December. From 1880 to 1883, Félix Ravaisson-Mollien, the director of the Department of Antiquities, decided to rebuild the memorial in the style of Austrian archaeologists.

On the figure’s torso, he plastered the belt region, inserted the right portion of the stone bust, plastered the left part, joined the left marble wing with a metal structure, and plastered the whole right-wing. He did not, however, recreate the face, or limbs. Excluding the damaged bow of the keel, the ship-shaped foundation has been repaired and finished, but there is still a vast hole at the top aft. The sculpture was positioned exactly on top of the base.

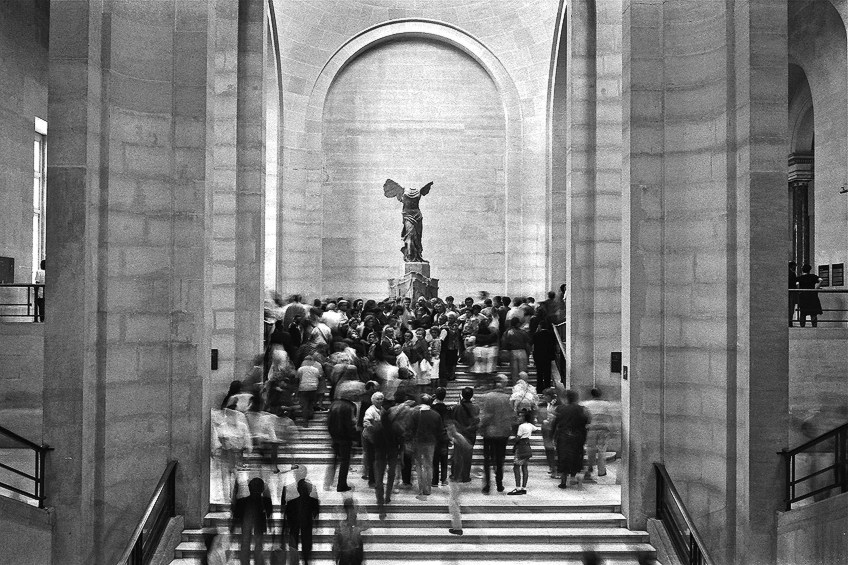

The complete memorial was subsequently positioned from the front, on the higher landing of the Daru stairway, the gallery’s main grand staircase.

Champoiseau came to Samothrace a third time in 1891 to try to recover Nike’s head but was unsuccessful. He did, nevertheless, bring back rubble from the draperies and foundation, as well as a tiny portion with an engraving and some colored plaster bits.

Restorations in the 20th century

In 1924 the Winged Victory of Samothrace display was changed as part of a comprehensive renovation of the Daru Museum and stairway, whose stairs were expanded and renovated. The memorial was presented to be the capping of the stairway: it was forwarded on the platform to be more apparent from the bottom of the stairs, and the sculpture was improved on the foundation by a contemporary 45 cm high stone block, which was meant to recall a fighting bridge at the edge of the boat.

Until 2013, this layout remained unmodified. When the Second World War was declared in September 1939, the Nike of Samothrace statue was dropped from its pedestal to be removed and hidden with the other wonders of the Louvre Museum. It stayed in the Château de Valençay until the Liberation and was reinstalled at the top of the staircase in July 1945, unscathed.

In 1938, Under the leadership of Karl Lehmann, American excavators from New York University continued investigation of the shrine of the Great Gods in Samothrace. In July of 1950, they linked their research to Louvre curator Jean Charbonneaux, who uncovered the palm of the monument’s right hand in the Victory location.

Two fingers that had been kept in the Kunsthistorische Museum in Vienna since the 1875 Austrian excavations were reattached to the hand.

The hand and digits were later donated to the Louvre Museum, where they have been displayed beside the monument since 1954. In 1952, two slabs of grey marble used to anchor fishing vessels on the beach underneath the site were recovered and reconstructed in the museum. Ira Mark and Marianne Hamiaux investigated them in 1996 and found that these fragments, when joined, comprise the block of the base discarded in 1879 by Champoiseau.

21st Century Restorations of the Winged Victory of Samothrace

From 2008 to 2014, an American team digitized the whole sanctuary in order to enable 3D restoration. Continuation of the research of the Victory perimeter and the modest basic parts maintained in preservation started in 2013 and 2014, under the leadership of B. D. Wescoat. The Louvre Museum initiated the repair of the complete monument with two goals in mind: to cleanse all of the unclean surfaces and to enhance the overall appearance.

The sculpture was removed from its foundation to be examined scientifically (UV, X-rays, marble analysis): remnants of blue paint were found on the wings and a band at the base of the mantle. The base’s blocks were dismantled one by one in order to be sketched and analyzed.

The monument’s 19th-century repair is kept with a few details (narrowing of the neck and connection of the left arm), elements from the Louvre’s collection are inserted (feather at the upper left wing, a wrinkle at the rear of the chitôn), and the metal clamp behind the left leg was taken away. Molds of minor joint pieces found in Samothrace have been incorporated onto the foundation. A casting of the massive vessel block remaining in Samothrace was substituted by a metal base on a cylinder to ensure the monument’s appropriate balance. When the marbles of the two components are placed on the foundation, the color difference of the stones of the two components becomes apparent once again.

The entire structure is reconstructed on a contemporary base, a little distanced on the platform to enable visitor flow.

Description of the Winged Victory of Samothrace

The statue, made of white Parian marble, shows Nike, a winged lady, landing on the bow of a vessel. Nike wears a long garment of a beautiful cloth with folded flaps and a belted beneath the breast. Two small straps held it to the shoulders. The lower body is partly concealed by a thick mantle, which is rolled up at the waistline and unties when the full left leg is shown; one end drops between the thighs to the floor, while another, much smaller, flies openly in the rear.

The mantle is slipping from her shoulders, and only the power of the wind keeps it on her right leg. The sculptor has increased the impressions of drapery by displaying the contours of the cloth where it is pressed against the body, notably on the stomach, and where it gathers in folds profoundly hollowed out generating a dramatic shadow, as between the thighs.

This great virtuosity affects the monument’s left flank and front. The drapery pattern on the right-hand side is limited to the primary lines of the garments, in a considerably less complicated design. The goddess moves forward, resting on her right leg. The two naked feet vanished into thin air. The right foot reached the floor, the heel remained slightly lifted; the left foot was still hoisted in the sky, the leg forcefully extended back. The deity isn’t strolling; she’s just finished flying, her enormous wings extended out backward.

The deity made a triumphant gesture of redemption with her elbow angle: this hand with spread fingers contained nothing (neither crown nor trumpet).

There is no information to recreate the posture of the deity’s left arm, which was most likely lowered and somewhat bent; the deity may have clutched a stylus on this side, a type of mast captured as a trophy aboard the enemy vessel, as depicted on coins. The sculpture is intended to be viewed from three-quarters left, from which the piece’s lines are quite evident: a straight from the neck to the right foot, and an oblique beginning from the head diagonally all along the left leg. Unlike previous Near Eastern or Greek sculptures, the Nike establishes an intentional link with the imagined area surrounding the goddess.

The wind that has brought her and that she is battling against, striving to remain stable – as already indicated, the initial mounting had her poised on a ship’s prow, just having arrived – is the model’s unseen companion, and the viewer is compelled to picture it. Simultaneously, the larger expanse heightens the work’s metaphorical impact; the winds and the ocean are presented as symbols for conflict, fate, and supernatural aid or mercy. Around two thousand years later, this type of interaction between a sculpture and the environment dreamed up would become a prominent technique in Romantic and Baroque art.

The boat and the base were sculpted from grey marble from the Lartos quarry in Rhodes. The foundation is shaped like the bow of a Greek Hellenistic naval vessel: narrow and long, it is capped in front by a fighting deck, which houses the sculpture.

On the sides, it had strengthened, protruding oars frames that held two rows of uneven oars. The keel has a rounded shape. The massive triple-pronged spur was shown at the base of the bow, near the level, and a smaller two-bladed ram was depicted somewhat higher up: which would be used to break the hull of the opposing vessel. A high and curving bow decoration adorned the top of the bow. These lost parts have not been restored, reducing the vessel’s warlike look significantly.

The Function of the Nike of Samothrace Statue

The devout presented their ex-votos at the sanctuary, ranging from the simplest to the most luxurious according to their riches. It was a way to honor the gods and express gratitude for their blessings. In addition to a hope of a new spiritual existence, the Cabeiri gods were said to defend people inducted into their Rituals if they were in peril at sea or in war.

By calling them, they were able to save their disciples from drowning and win the battle. In this perspective, a depiction of Victory arriving on the bow of a vessel might be regarded as a tribute to the Ancient Divine beings following a significant naval triumph. In the third century BC, there were many notable naval contributions.

In the Greek world, for example, the agora naval monument in Cyrene and Samothrace itself, the “bull monument” in Delos, the Neorion, which contained a ship around 20 meters in length. A tribute of the same sort as the foundation of Samothrace, although smaller in size, was discovered at the summit of Lindos’ acropolis at the shrine of Athena.

Dating of the Winged Victory of Samothrace

The sculpture’s dedication inscription has not been discovered. Archaeologists are forced to speculate in order to establish the historical context and discover the naval victory that justifies the creation of such a significant ex-voto. The problem is that in the second and third century BCE. During this time, naval wars for control of the Aegean Sea were frequent, opposing the Seleucids against the Pergamon.

Austrian researchers originally assumed that the Samothrace statue was the one seen on Demetrios Poliorcetes’ tetradrachm. They assume that he used the currency to commemorate his triumph against Ptolemy I at the 306 BC Battle of Salamis.

Based on the writings of Benndorf, the “Winged Victory of Samothrace” was carved in the later years of the fourth century BC by a disciple of artist Scopas.

The Workshop and Style of the Statue

Despite the fact that the alleged dedication inscription of a Rhodian’s name located at the Victory’s base was swiftly questioned due to its modest size, the whole monument was credited to the Rhodian sculptural school. This put an end to any prior reservations regarding the statue’s design. Margarete Bieber elevated him to the ranks of the “Rhodian school” and the “Hellenic Baroque” in 1955, alongside the frieze of the Gigantomachy of the Great Altar of Pergamon, which was distinguished by the resilience of perceptions, the brilliance of the draperies, and the liveliness of the figures.

This style persisted in Rhodes until Roman times, manifesting itself in intricate and colossal works such as the Laocoon set or Sperlonga statues credited or inscribed by Rhodian artists. The foundation blocks and the monument’s carving are not by the same artist. The two halves of the memorial were conceived jointly but built by two separate workshops. Lartos’ marble base was almost definitely created in Rhodes, where there are analogs.

Furthermore, while the Rhodian sculpting in big marble is of good quality, but not outstanding for its period, there are no analogs for the dexterity of the Nike, which remains unique.

The sculptor might have originated from somewhere else, as was customary for renowned artists in ancient Greek society. The Winged Victory of Samothrace is a magnificent modification of the Athena-Niké of Cyrene monument’s moving monument: the artist added wings, extended out his front leg to indicate movement, and changed the placement of the mantle with the floating panel at the rear.

That brings to a close our fascinating exploration of the incredible “Nike of Samothrace” statue. The “Winged Victory of Samothrace” is another name for the “Nike of Samothrace” statue. Although it was created in the 2nd century BC, it was not rediscovered until the 1860s. Following that, it went through multiple restoration processes. It is a world-renowned Hellenistic-era Greek sculptural masterwork and depicts the goddess of triumph Nike.

Take a look at our Winged Victory of Samothrace webstory here!

Frequently Asked Questions

Who Made the Winged Victory of Samothrace?

The foundation blocks and the monument’s statue are not by the same artist. The two halves of the monument were conceived jointly but built by two separate workshops. Lartos’ marble base was almost definitely created in Rhodes, where there are analogs. Furthermore, while the Rhodian sculpture in big marble is of good quality but not outstanding for its period, there are no analogs for the virtuosity of the Nike, which remains unique. The sculptor might have originated from somewhere else, as was customary for renowned artists in ancient Greek society. Now housed at the Louvre Museum, it is not known who made the Winged Victory of Samothrace, but it is believed to have been ordered to be built by Demetrius Poliocretes sometime between 295 and 290 BC

What Was the Nike of Samothrace Statue Created For?

The Winged Victory of Samothrace is a unique Greek sculpture whose original site is known. It was created as a sacrifice to the gods for a shrine on the Greek island of Samothrace. It was built not just in tribute to the goddess Victory, but also to commemorate a naval battle. It provides a sense of movement and victory while also depicting elegant flowing fabric as if the goddess were falling to land on the prow of a boat. At a very early age, the Greeks depicted ideals such as Harmony, Prosperity, Wrath, and Judgment as deities. The victory was among the first of these manifestations.

From Which Period and Style Is the Winged Victory of Samothrace?

The Nike, made of Parian marble, is a remarkable instance of the emotive, Hellenistic style. The vibrant draperies, twisting posture, and dramatic background combine to produce a dynamic composition reminiscent of Pergamon art. The statue was discovered in 1863 and uncovered under the supervision of the French Vice-Consul to Turkey, Charles Champoiseau, In the fourth century BCE, this method of double-girding a female’s garment was quite common.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Nike of Samothrace – History of the Winged Victory Sculpture.” Art in Context. November 26, 2021. URL: https://artincontext.org/nike-of-samothrace/

Meyer, I. (2021, 26 November). Nike of Samothrace – History of the Winged Victory Sculpture. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/nike-of-samothrace/

Meyer, Isabella. “Nike of Samothrace – History of the Winged Victory Sculpture.” Art in Context, November 26, 2021. https://artincontext.org/nike-of-samothrace/.