Nefertiti Bust – Discover the Iconic Egyptian Bust of Nefertiti

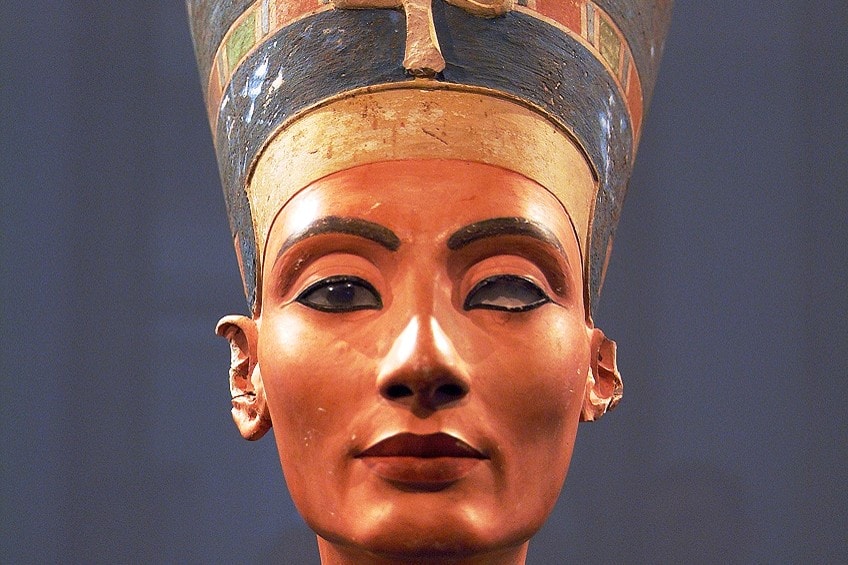

The famous bust of Nefertiti, made from limestone, is a statue representing the pharaoh of Egypt Akhenaten’s Royal Wife. Because it was discovered at Thutmose’s studio in Amarna, Egypt, the bust of Nefertiti is thought to have been created about 1345 BCE. The Queen Nefertiti statue is one of ancient Egypt’s most reproduced masterpieces. Nefertiti became one of the most celebrated women of the ancient world and an ideal of feminine perfection as a result of the Egyptian bust.

The Nefertiti Bust (1345 BCE)

| Date Completed | 1345 BCE |

| Medium | Limestone and stucco |

| Dimensions | 48 cm |

| Current Location | Neues Museum, Berlin |

The bust was found in Thutmose’s workshop in 1912 by a German archaeological expedition. The sculpture of Nefertiti has become a cultural emblem for both Berlin and ancient Egypt. It was also the subject of a bitter dispute between Germany and Egypt over Egyptian requests for its repatriation.

This dispute started in 1924 when the bust was first publicly shown.

Thutmose: Sculptor of the Bust of Nefertiti

| Nationality | Egyptian |

| Date of Birth | c. 14th century BCE |

| Place of Birth | Egypt |

| Known for | Sculptor |

Thutmose was a sculptor in Ancient Egypt. He lived about 1350 BC and is supposed to have been the Egyptian pharaoh Akhenaten’s official court sculptor in the latter half of his reign. In early December 1912, a German archaeological excursion busy digging in Akhenaten’s abandoned city of Akhetaten discovered a destroyed residence and workshop complex; the structure was recognized as Thutmose’s predicated on an ivory horse blinker discovered in a garbage pit in the yard marked with his title and job description.

The conclusion appeared obvious and has shown to be correct because it listed his profession as “sculptor” and the structure was definitely a sculpting workshop.

A handful of the pieces discovered at the studio exhibit realistic portraits of elderly noblewomen. One of the plaster faces represents an elderly woman with wrinkles around her eyelids and a heavily lined forehead. “A larger range of wrinkles than any previous picture of an aristocratic woman from ancient Egypt,” according to the artist. It is considered to depict the idea of an elderly woman who is knowledgeable.

This was considered unusual in Ancient Egyptian art, which tended to favor idealized depictions of women as constantly youthful, slim, and attractive.

History of the Queen Nefertiti Statue

Pharaoh Akhenaten established Atenism, a new monotheistic style of religion devoted to the Sun disc Aten. Nefertiti is a mysterious figure. She might have been an Egyptian royal by blood, a visiting princess, or the child of Ay, a top government official who succeeded Tutankhamun as king.

She may have reigned with Akhenaten. Akhenaten had six daughters from Nefertiti, one of whom married Nefertiti’s stepson Tutankhamun.

While it was once assumed that Nefertiti died or changed her name in the 12th year of Akhenaten’s rule, as per a limestone quarry inscription found at Dayr Abinnis “on the eastern bank of the Nile, about ten kilometers north of Amarna,” she was still healthy in the 16th year of her husband’s rule. After her husband’s demise, Nefertiti may have briefly been a monarch in her own right.

The sculptor Thutmose is said to have created the bust of Nefertiti about 1345 BCE. The bust has no inscriptions, but the unique crown, which she adorns in other surviving images, may positively identify it as Nefertiti.

Discovery

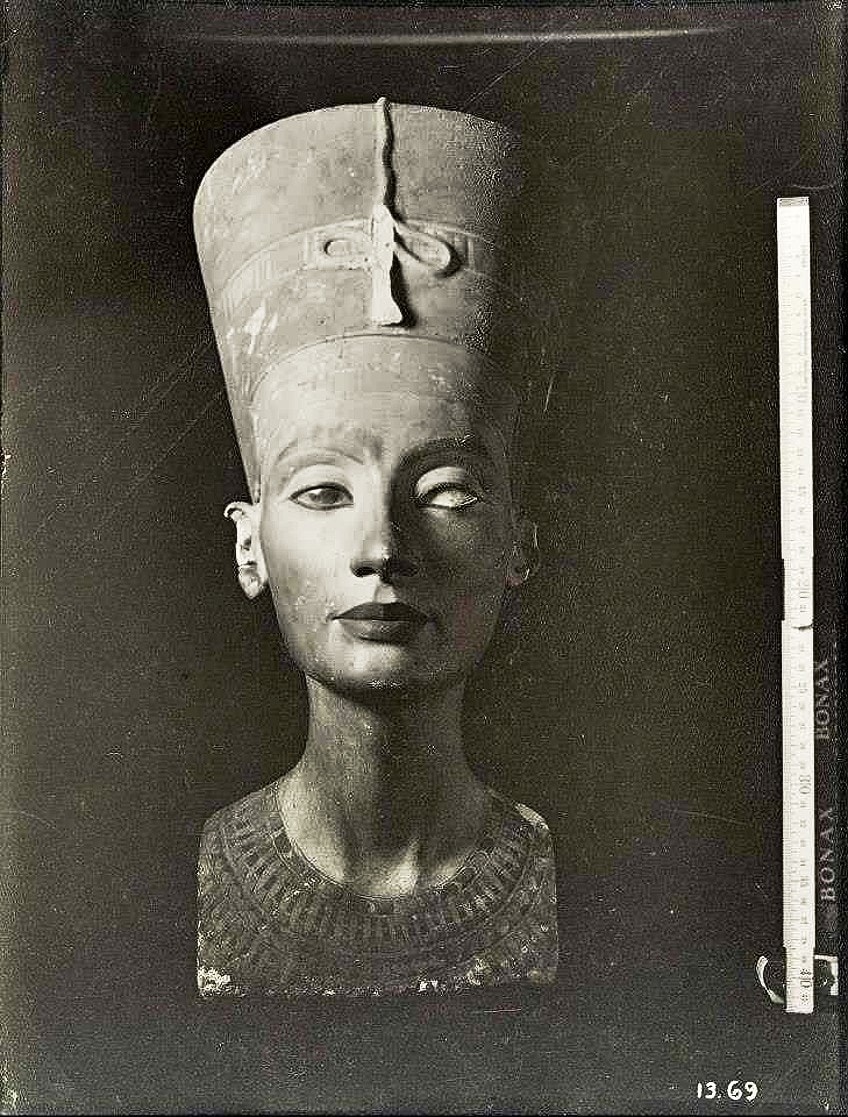

The German Oriental Company discovered the bust on December 6, 1912, in Amarna. It was discovered with other incomplete busts of Nefertiti at the artist Thutmose’s studio. Borchardt’s notebook is the primary documented description of the discovery.

He wrote, “Suddenly, we had the most living Egyptian artwork in our hands. A 1924 document discovered in the files of the German Oriental Company remembers a meeting between Borchardt and a top Egyptian official on January 20, 1913, to negotiate the partition of the 1912 archeological discovery between Germany and Egypt.” Borchardt “intended to safeguard the bust for us”, as per the secretary of the German Oriental Company. Borchardt is accused of concealing the bust’s true worth, despite his denials.

“Time” magazine cites the coup as one of the “Top 10 Plundered Antiques,” while Philipp Vandenberg calls it “daring and beyond compare.”

Borchardt presented an image of the bust to the Egyptian official that “didn’t put Nefertiti in her finest light.” When the chief antiquities inspector of Egypt arrived for an examination, the bust was packed in a box. Borchardt said the bust was constructed of gypsum to deceive Lefebvre, according to the paper.

Examination and Description

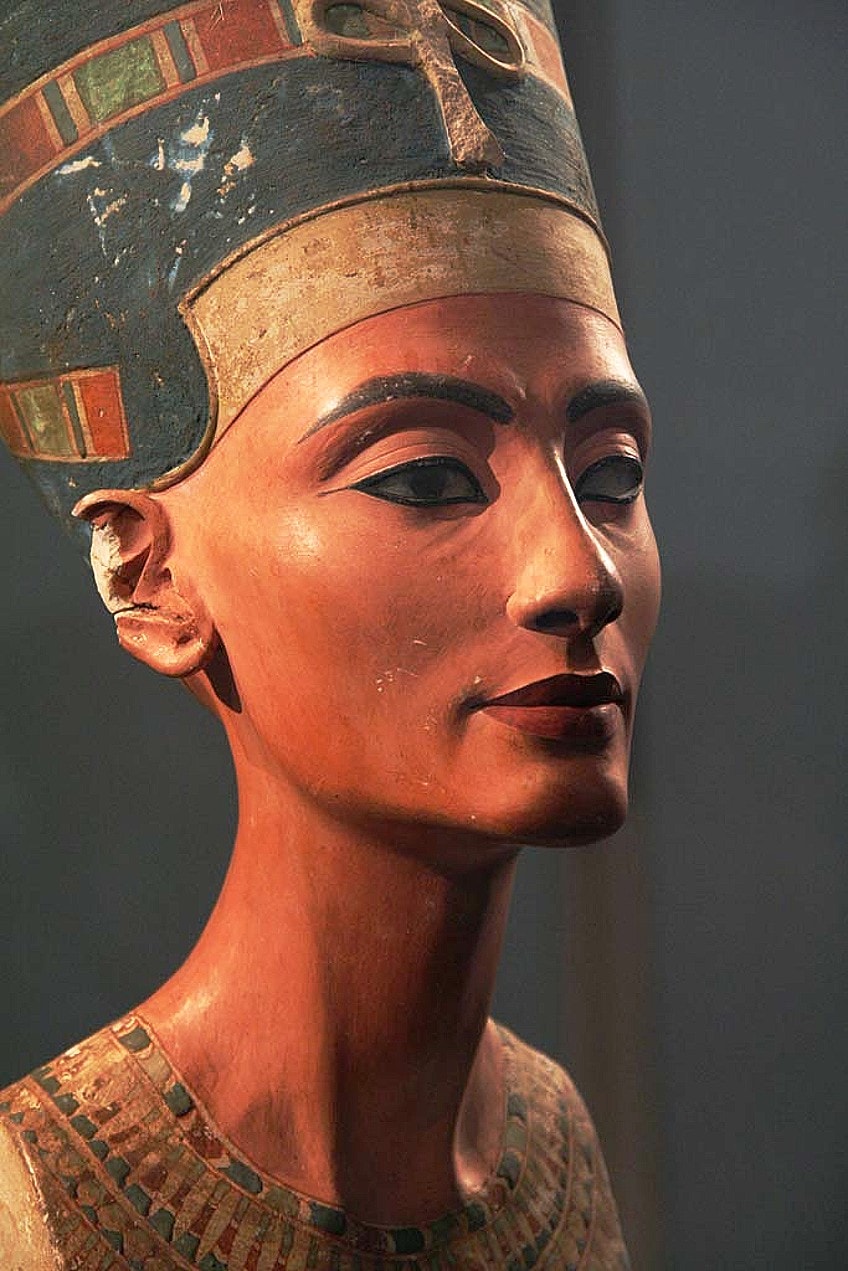

The Egyptian bust of Nefertiti stands 48 cm tall. It has a limestone core with painted stucco layers on top. The face is nearly entire and symmetrical, although the left eye lacks the inlay that is present in the right. The right eye’s pupil consists of implanted quartz painted black and sealed with beeswax. The eye socket has a plain limestone backdrop.

Nefertiti wears the “Nefertiti cap crown,” a blue crown with a golden diadem band wound around her head like horizontal bands and uniting at the rear, and a broken cobra over her brow. She also sports a floral-patterned wide collar.

Damage to the ears has also occurred. By emphasizing the weight of the domed head and the length of the nearly serpentine neck, Thutmose may have been alluding to a hefty flower on its long sleek stalk with this beautiful breast. The bust is in the ancient Egyptian art style, avoiding the “quirkiness” of Akhenaten’s Amarna artistic style.

The sculpture’s particular function is not yet known; however, it might be a sculptor’s model kept at the artist’s workshop to be used as a reference for subsequent portraits.

Missing Left Eye

When the bust was initially discovered, there was no quartz to depict the pupil of the left eye, as there was in the other eyeball, and nothing was located despite a thorough search and a £1000 prize for intelligence on its location. When Thutmose’s studio was destroyed, Borchardt imagined the quartz iris had dropped out.

The absence of an eye led to conjecture that Nefertiti may have lost her left eye due to an ophthalmic illness, however, the presence of an iris in other sculptures of her refuted this theory.

The bust in Berlin, according to Dietrich Wildung, was used as a template for official portraits and was utilized by the master sculptor to teach his pupils how to sculpt the interior anatomy of the eye, therefore the left iris was not inserted. Others have the opinion that the bust was left incomplete on purpose.

Thutmose may have developed the left eye, but it was eventually destroyed, according to Zahi Hawass.

CT Scans

Queen Nefertiti was CT scanned for the first time in 1992, with the scans producing cross-sections of the statue every five millimeters. While testing with various illumination techniques at the Altes Museum in 2006, Dietrich Wildung could make out many wrinkles on the bust’s neck area, as well as noticeable bags under her eyes, hinting the artist had intended to convey indications of age. Thutmose had placed gypsum behind the cheekbones and eyes in an attempt to refine his sculpture, according to a CT scan.

In 2006, a CT scan performed by Alexander Huppertz showed a wrinkled face of Nefertiti engraved in the bust’s inner core. These findings were made public in April 2009.

Thutmose built layers of different thicknesses on top of the limestone core, according to the scan. The inner face contains wrinkles around her lips and cheeks, as well as a nose swelling. The outermost stucco layer evens out the wrinkles and bumps on the nose.

The 2006 scan revealed more resolution than the 1992 scan, displaying minor features 1–2 mm beneath the stucco.

Later History

The Nefertiti Bust has become one of ancient Egypt’s most admired and imitated pictures, as well as the flagship exhibition used to sell Berlin’s museums. It is regarded as an international beauty symbol. The bust, which depicts a woman with a long neck, gracefully arched brows, high cheekbones, a thin nose, and an enigmatic grin played around crimson lips, has cemented Nefertiti as one of antiquity’s most gorgeous women.

It is said to be the most famous bust in ancient art, second only to Tutankhamun’s mask.

Locations in Germany

Since 1913, when it was relocated to Berlin and handed to James Simon, the monument has remained in Germany. The statue was displayed in his homestead until around 1913, after which he donated it to the Berlin Museum. The remainder of the Amarna collection was shown in 1914, but the bust was kept hidden at Borchardt’s request. The museum debated displaying the bust publicly in 1918 but again kept it hidden at the behest of Borchardt.

In 1920, it was formally presented to the museum. The bust caused a stir, quickly becoming a world-renowned image of feminine perfection and one of the most widely recognized ancient Egyptian objects to exist.

Controversies

Egyptian officials have requested the bust’s repatriation to Egypt since its formal debut in Berlin in 1924. Egypt threatened to prohibit German digs in Egypt unless the statue was repatriated in 1925. Egypt offered to swap other treasures for the bust in 1929, but Germany refused.

Repatriation Requests

Despite Germany’s earlier strong opposition to repatriation, Hermann Göring proposed returning the bust to Egypt’s King Farouk Fouad as a political gesture in 1933. Hitler was opposed to the plan and promised the Egyptian authorities that he would construct a new Egyptian museum in her honor. “This marvel, Nefertiti, will be seated in the midst,” Hitler predicted.

While the statue was under American hands, Egypt demanded that it be returned; the US refused, advising Egypt to take the matter up with the new German authorities. Egypt attempted to restart discussions in the 1950s, but Germany did not respond. Egypt attempted to restart discussions in the 1950s, but Germany did not respond. Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak visited the bust in 1989 and declared Nefertiti to be “the finest ambassador for Egypt” in Berlin.

Zahi Hawass argued that the bust belonged to Egypt and that it had been unlawfully removed from Egypt and should thus be returned.

He contended that Egyptian officials were deceived about the bust’s acquisition in 1913 and requested that Germany verify that it was shipped properly. Another rationale for return is that archeological finds truly belong in their original homeland and ought to be protected in that country. Hawass threatened to halt Egyptian artifact exhibitions in Germany if the sculpture was not repatriated to Egypt in 2007, but he was ineffective.

He also advocated for a worldwide embargo on lending to German museums to start a “scientific war.” Hawass hoped that Germany would give the bust to Egypt for the launch of the new Grand Egyptian Museum nearby the Great Pyramids of Giza in 2012. Concurrently, the cultural organization CulturCooperation, located in Hamburg, Germany, started a campaign named “Nefertiti Travels.”

They circulated postcards with the phrase “Return to Sender” displaying the sculpture and sent an opinion piece to German Culture Minister, expressing the opinion that the bust should be loaned to Egypt.

Several German art specialists have sought to contradict all of Hawass’ assertions, citing a 1924 paper that discussed the deal between Borchardt and Egyptian officials. German officials have also said that the sculpture is too fragile to move and that the legal justifications for repatriation are weak. According to The Times, Germany is fearful that giving the bust to Egypt may result in Egypt’s irreversible exit from Germany. Friederike Seyfried submitted the Egyptians with paperwork related to the Egyptian bust’s discovery, including a document signed by the German digger in December 2009.

The bust was identified in the records as a painted plaster statue of a royal, but Borchardt definitely alluded to it as Nefertiti’s head in his notebook.

“This demonstrates that Borchardt wrote this description in order for his country to receive the monument,” Hawass remarked. “These documents support Egypt’s claim that he acted unethically with the purpose to mislead.” However, according to Hawass, Egypt does not consider the Nefertiti Bust to be a plundered antique. “I absolutely need that back,” he explained.

Authenticity Allegations

According to several books, the bust is a recent forgery. It is thought that Borchardt may have made the Queen Nefertiti statue to experiment with ancient colors, and when it was appreciated by Prince Johann Georg of Saxony, Borchardt declared it was real to prevent upsetting the prince. Stierlin believes that the sculpture’s missing left eye was a mark of contempt in ancient Egypt, that no academic documentation of the bust exists until 11 years after its reported rediscovery, and that, while the painting pigments are old, the inner limestone foundation has never been verified.

Ercivan believes Borchardt’s spouse was the inspiration for the statue, and both writers believe it was hidden from the public until 1924 because it was a forgery.

Another story indicated that the extant bust was made on Hitler’s instructions in the 1930s and that the first was lost during WWII. Dietrich Wildung denied the accusations as a publicity ploy, citing radiological studies, extensive computer tomography, and material analysis as proof of their veracity. The colors used on the bust were chosen to be similar to those employed by ancient Egyptian artists.

According to Science News, the CT scan that revealed Nefertiti’s “hidden face” in 2006 established that the bust was authentic.

Stierlin’s idea was likewise disregarded by Egyptian officials. Hawass stated, “Stierlin does not claim to be a historian. He is insane.” Thutmose, according to Hawass, developed the eye, but it was subsequently destroyed.

Body of the Nefertiti Bust

The Egyptian Museum in Berlin granted permission in 2003 for a Hungarian artist couple to set the bust atop a virtually naked female bronze for a video work to be displayed at the Venice Biennale modern art exhibition. The artists described the Body of Nefertiti project as an attempt to pay tribute to the bust. It demonstrated the ongoing significance of the old world to the art of today.

Egyptian officials of culture declared it a travesty to “one of their country’s major emblems of history” and barred Wildung and his spouse from the future investigation in Egypt.

A freedom of information application was submitted to the Egyptian Museum in 2016 for access to a full-color scan of the bust made by the museum ten years earlier. The museum refused the proposal due to the potential effect on gift shop sales. The Cultural Heritage Foundation, which manages the museum, subsequently made the document available, which is publicly available (albeit not straight from the institution), however, a disputed license was attached to the piece, which is in the public realm.

Cultural Significance

The German press referred to the statue as their new ruler, portraying it as a queen in 1930. After 1918, Nefertiti would re-establish the imperial German identity as the “‘most beautiful stone in the arrangement of the diadem’ from the artistic riches of ‘Prussia Germany.'” Hitler referred to the statue as “a one-of-a-kind masterwork, an adornment, a great treasure,” and promised to create a museum to house it.

By the 1970s, the Queen Nefertiti statue had become a matter of national identity for both of Germany’s postwar nations, East Germany and West Germany.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D_dbSjJMS_Y

The bust was first featured on an election billboard for the green political party Bündnis 90/Die Grünen in 1999 as a pledge for a multicultural atmosphere under the motto “Great Women for Berlin!” As per Claudia Breger, another reason the bust became identified with German national character was its role as a competitor to Tutankhamun, who was discovered by the British who dominated Egypt at the time.

One of Ancient Egypt’s most renowned masterpieces is the bust of Nefertiti, which is held at Berlin’s Neues Museum. This symbol has been dubbed “the most beautiful woman in the world” and is a remarkable example of ancient workmanship. Since its debut in 1923, the monument has mesmerized audiences by providing insight into the mysterious queen and has sparked controversy and discussion in art and political discussions.

Frequently Asked Questions

Who Created the Queen Nefertiti Statue?

Thutmose was an Egyptian sculptor. He lived circa 1350 BC and was the royal palace sculptor of Egyptian monarch Akhenaten in the latter portion of his rule. A destroyed workshop was proven to be his and contained the famous bust of Nefertiti.

Who Does the Egyptian Bust Represent?

The Queen Nefertiti statue is a stone sculpture of the bride of Egyptian Pharaoh Akhenaten. The bust of Nefertiti is considered to have been produced about 1345 BCE since it was unearthed at Thutmose’s workshop in Amarna, Egypt. One of ancient Egypt’s most replicated masterpieces is the Queen Nefertiti statue. As a result of the Egyptian bust, Nefertiti is positioned among the most recognized ladies of the ancient world and an ideal of female perfection.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Nefertiti Bust – Discover the Iconic Egyptian Bust of Nefertiti.” Art in Context. May 22, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/nefertiti-bust/

Meyer, I. (2022, 22 May). Nefertiti Bust – Discover the Iconic Egyptian Bust of Nefertiti. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/nefertiti-bust/

Meyer, Isabella. “Nefertiti Bust – Discover the Iconic Egyptian Bust of Nefertiti.” Art in Context, May 22, 2022. https://artincontext.org/nefertiti-bust/.